Project Risks Influence on Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Financing Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Undervaluation of the water resource;

- Insufficient cost recovery for investments due to water service underpricing;

- Need for high up-front and sunk investment followed by a very long payback period;

- Difficulty in monetizing the water management benefits, which undermines potential revenue flows;

- Lack of analytical tools and data to assess and track investments;

- Small dimension and specificity of WSS projects, which raise the transaction costs and hinder scaling-up;

- Prioritization of bankable projects over the maximization of social and environmental benefits; and

- Failure to support operation and maintenance efficiency.

- Regulatory and political risks usually arise when there is an instability risk in the political and financial status of a country and when there is a possibility that government exploitation of vulnerabilities in contracts, or other types of problems/abuses, will not be mitigated by a well-adjusted regulation system [14,15]. Typically, financiers do not understand the WSS sector and often fear the political nature of tariff setting and the perceived unwillingness of the population to pay for such services [16]. According to Jiang et al. [12] foreign direct investment is sensitive to political risk;

- Construction risk is inherent to any infrastructure project that involves a construction element and is related to the costs of the project [15,17]. Costs escalation can be due to unanticipated events, such as changes in environmental or geotechnical conditions, construction materials’ cost increases, an extension of the projected duration, and others [17,18];

- Performance and technical risks arise because of leakage or burst problems, the aging of the infrastructures, and the obsolescence of technologies [16]. The proper functioning of WSS infrastructure is highly dependent on considerable capital investments. To mitigate this risk is necessary to promote periodic rehabilitation and maintenance of the infrastructures (to minimize physical/real and billing water losses) and to update applied technologies when necessary or possible;

- Environmental and social risks are increasingly relevant topics for WSS, with water scarcity as one of the main problems that need to be addressed to ensure that everyone has access to safe and reliable water services. Water scarcity can be a threat to socioeconomic development and to the livelihood of many communities [19]. In addition, environmental and social risks could cause project delays, which can affect the reputation of the borrower and, in turn, generate credit risk [20]. Therefore, in order to attract commercial lending, it is important to incorporate “natural environment risk management strategies”, which are strategies that enable the identification and monitoring of the risk in project financing decisions and activities from an early stage [11];

- Exchange/currency rate risk can occur since the economic situation of developing countries is not usually stable and the exchange rate can suffer variations that were not predicted, thus resulting in variabilities in the value of, or in the interest in, a project [18,21]. Borrowings and investments that are serviced, repaid, or reimbursed in foreign currencies have an associated foreign exchange risk [14];

- The nature and importance of the sub-sovereign risk varies, since there are different types of borrowers (e.g., government bodies, affiliated entities, specific project entities, and utilities) and types of transactions (e.g., general obligations and revenue based on specific cash flow) [23]. Some lenders are concerned with the default risk associated with lending to sub-sovereign bodies [23];

- Contractual risk is prevalent since the life of water investments is long, with contracts that average between 25 and 30 years, while the available financing has a short tenure [14,16]. The willingness of the lenders to provide longer tenures depends on the perceived risk of the project, and since financiers are not familiar with the water sector it is sometimes wrongly labeled as a high-risk investment and financing consistently falls short of the needs [2,16]. According to Akintoye et al. [24], the benefits of investing in WSS projects can only be truly reached if the contractual risks are mitigated, since contracts that do not effectively address risk raise the costs associated with all types of infrastructure services;

- Other macroeconomic and business risks are also worth mentioning because of their impact on WSS projects, namely, the liquidity risk, which arises when there is an inability to exit or sell and is prevalent in infrastructure projects, since they are unique in terms of the services provided resulting in fewer liquid infrastructure investments [2,25]; operating risk, which relates to the potential weak performance of the utilities, including serious problems such as fraud, trading errors, and system failures [2,11]; and market risk, which is associated with price changes, and it is impacted by unpredictable or unexpected factors that affect the amount of WSS services sold or recovered through tariffs and the actual tariff applied [11,17,18].

- Investment Project Financing (IPF) provides financing to governments for the creation of physical and/or social infrastructures when they are accessed as “essential to reduce poverty and create sustainable development”. Thus, IPF is focused on the medium-to-long term (around 5 to 10 years) and supports a wide range of activities (e.g., capital-intensive investments, service delivery, and others), by supplying financing and acting as a “vehicle for sustained, global knowledge transfer and technical assistance”;

- Development Policy Financing (DPF) (also known as Development Policy Lending) provides budget support to governments or political subdivisions with a program of policy and institutional actions aimed at addressing bottlenecks to improve service delivery, strengthening public financial management and other endeavors. DPF allows for the provision of rapidly disbursed financing to help borrowers address development financing requirements, which can be current or predicted;

- Program-for-Results (PforR) disburses funds linked to the delivery of results that are defined in advance, to help countries improve their development programs design and implementation and strengthen their institutions and building capacity. PforR’s main goal is to enable countries to achieve lasting results. This type of financing instrument uses a “country’s own institutions and processes” and links the “disbursement of funds directly to the achievement of specific program results” [32].

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Number of Projects and Commitments

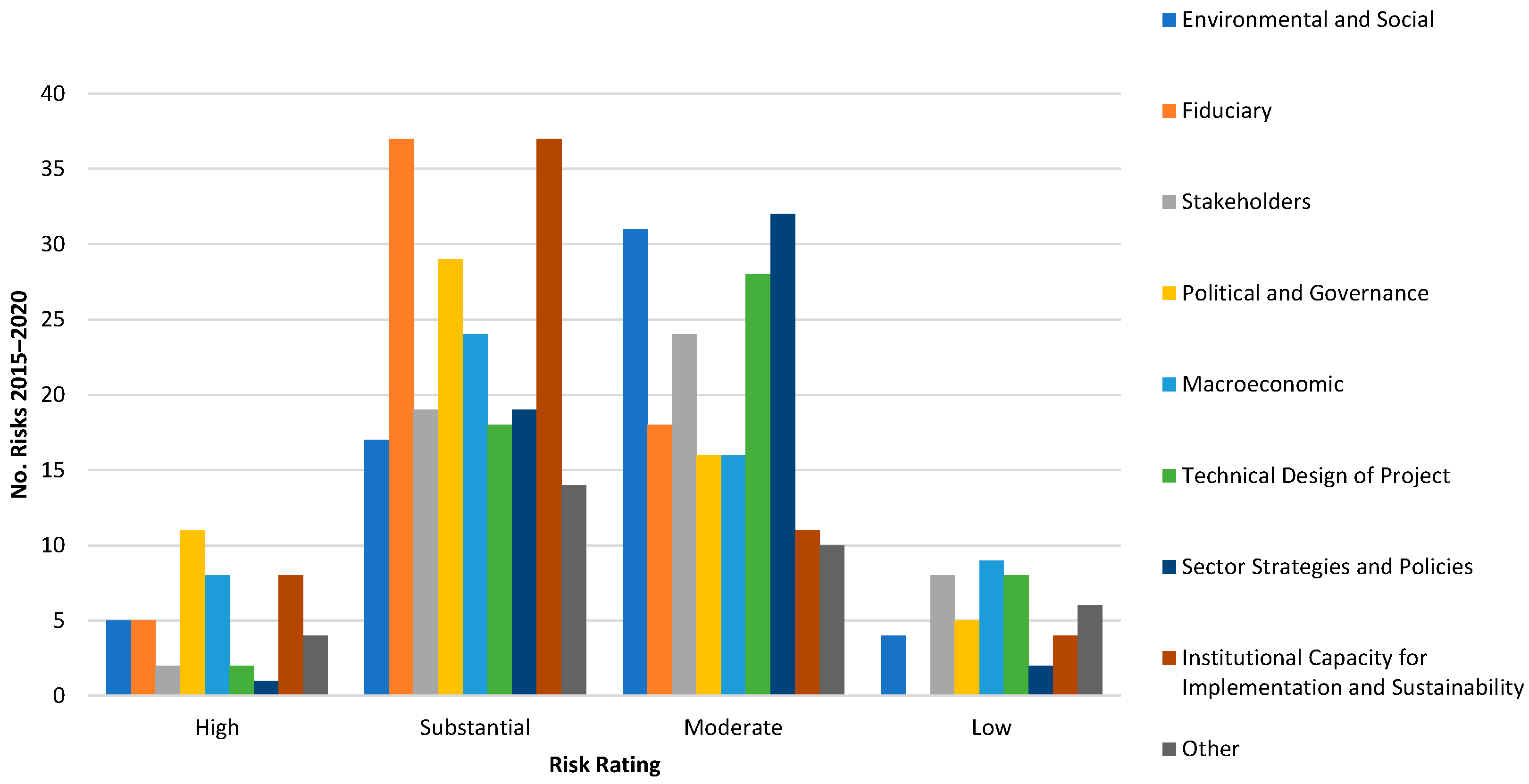

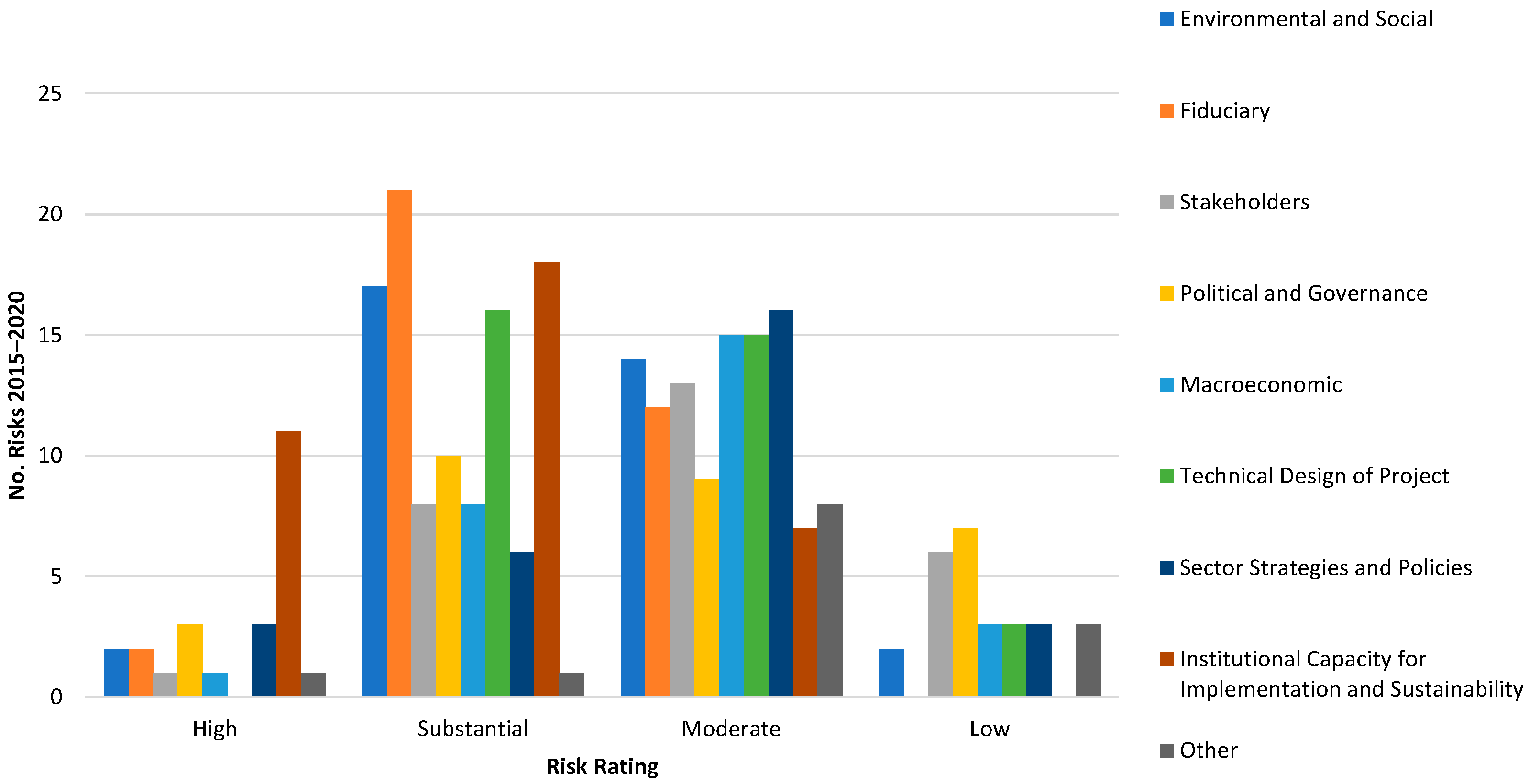

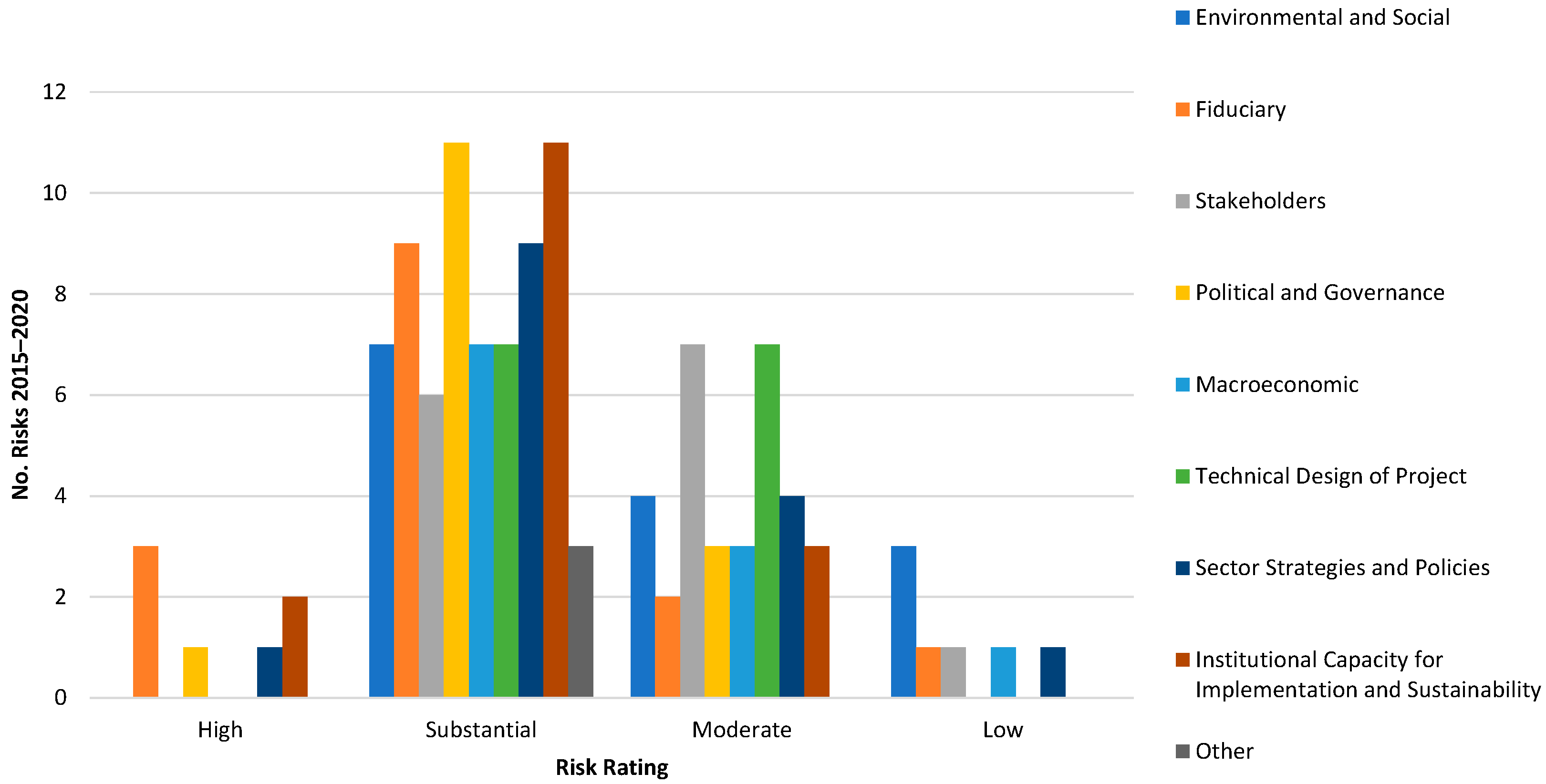

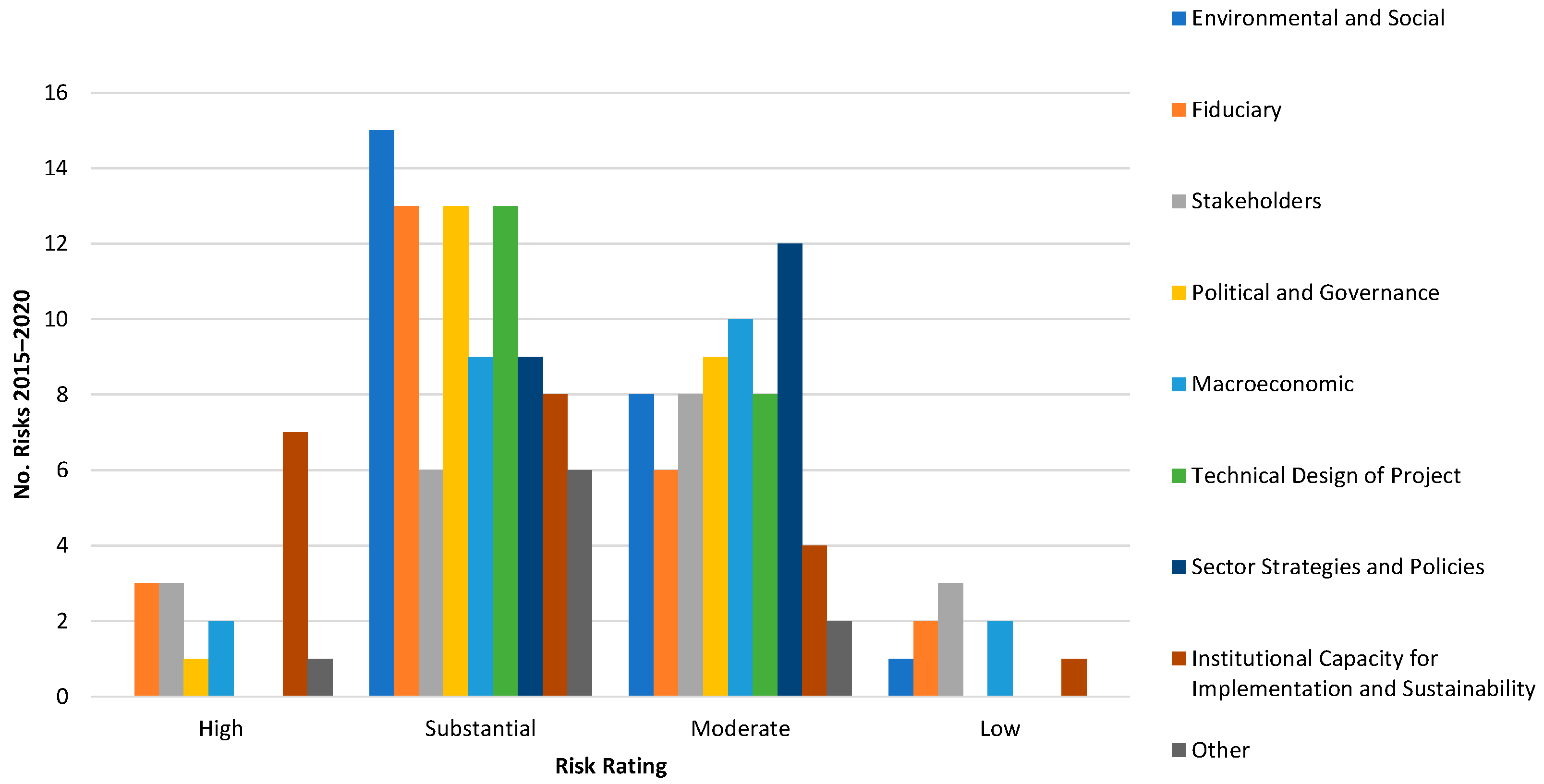

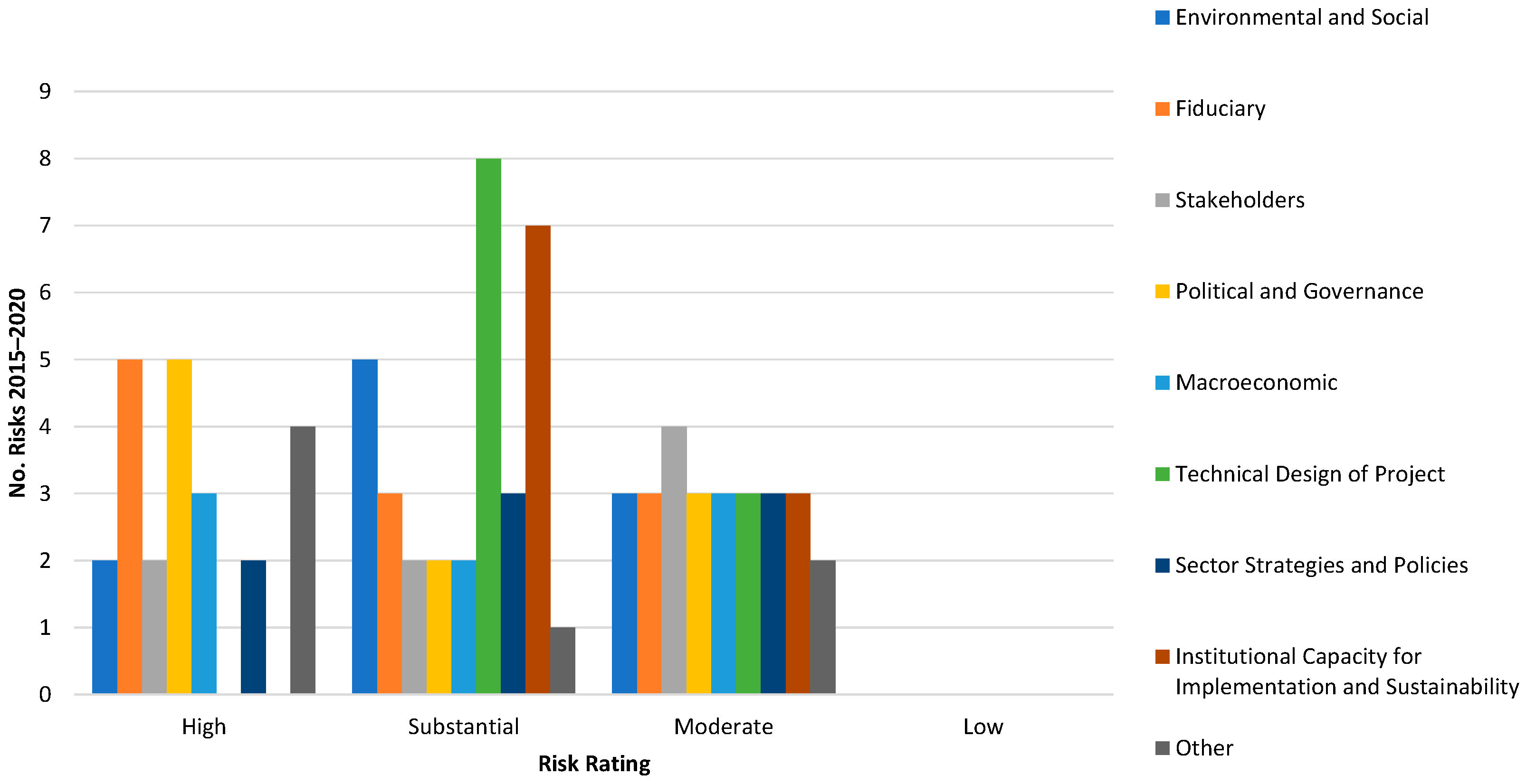

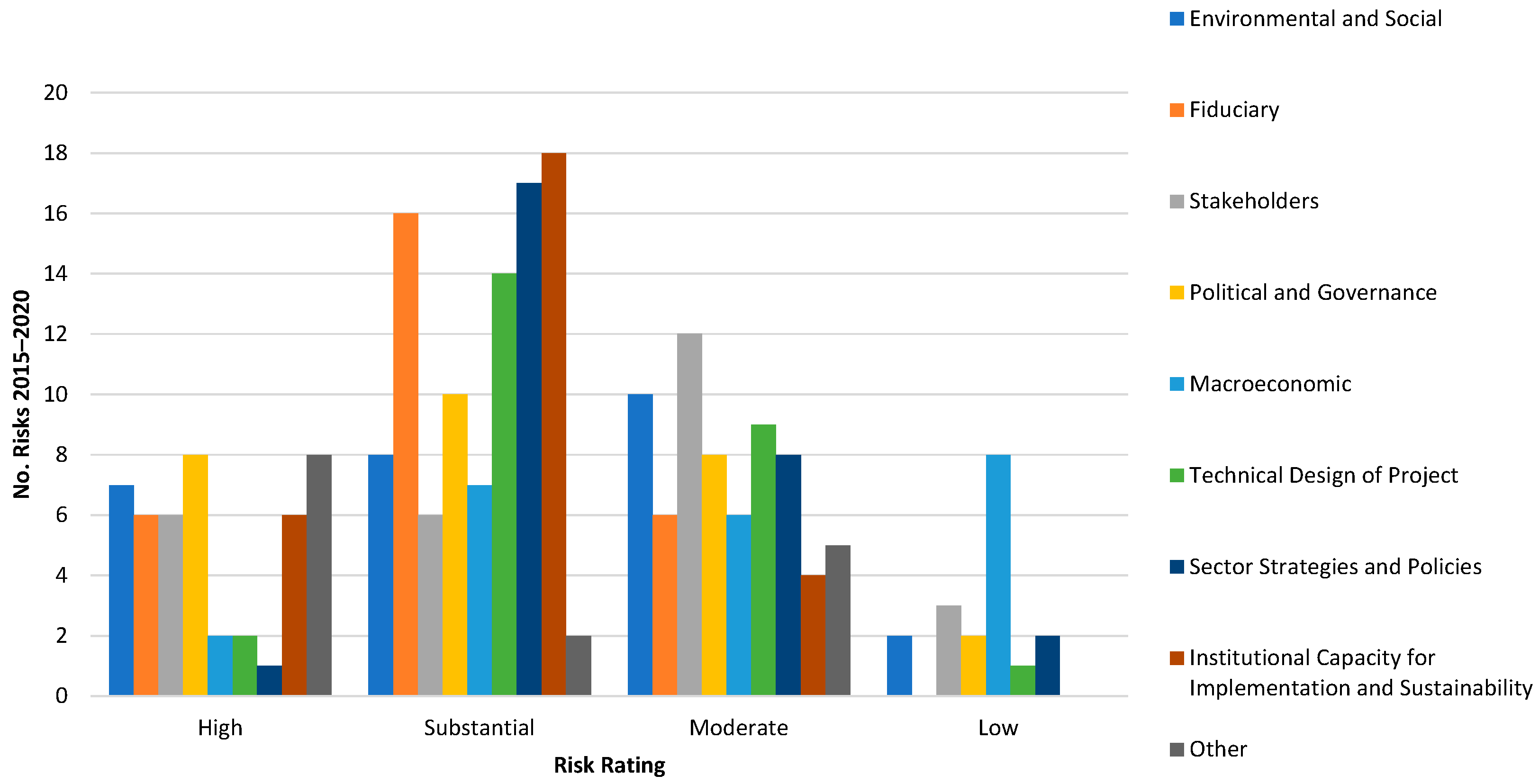

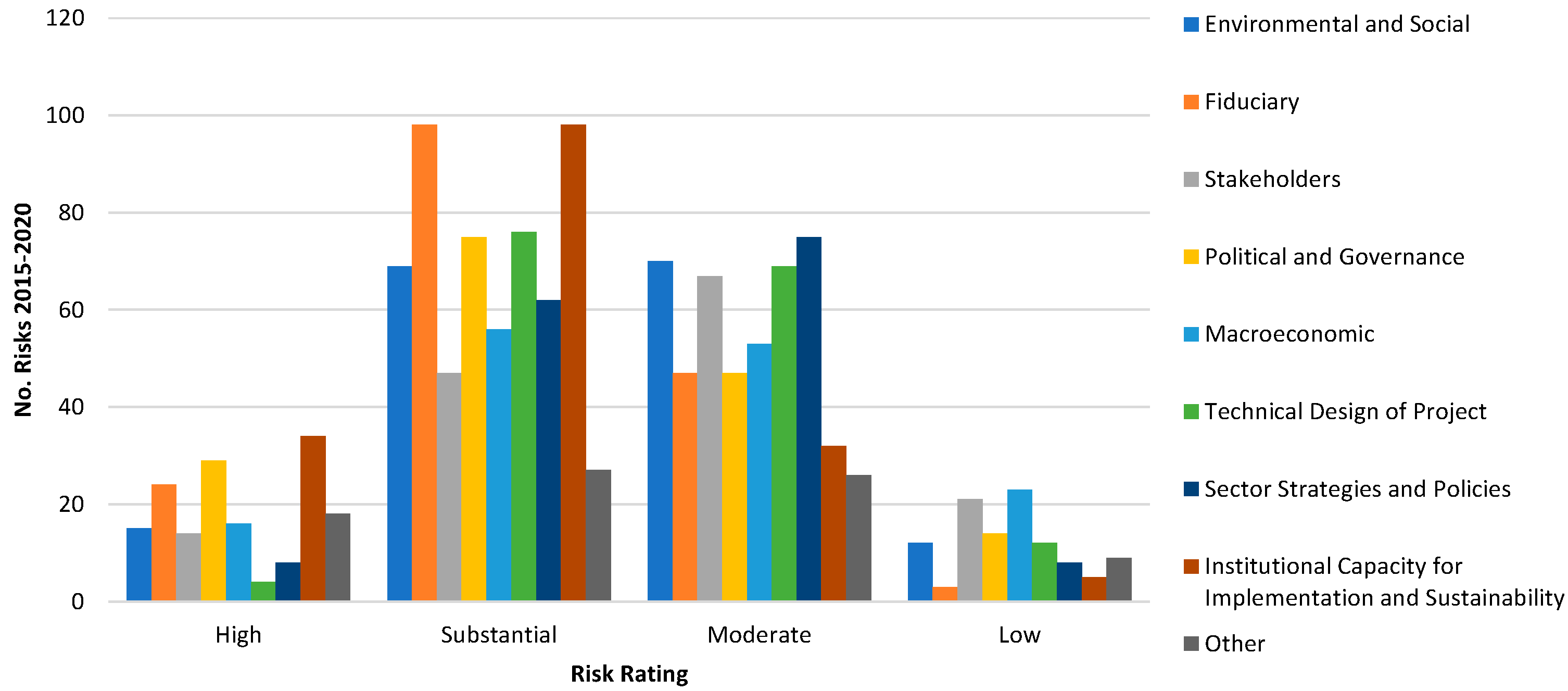

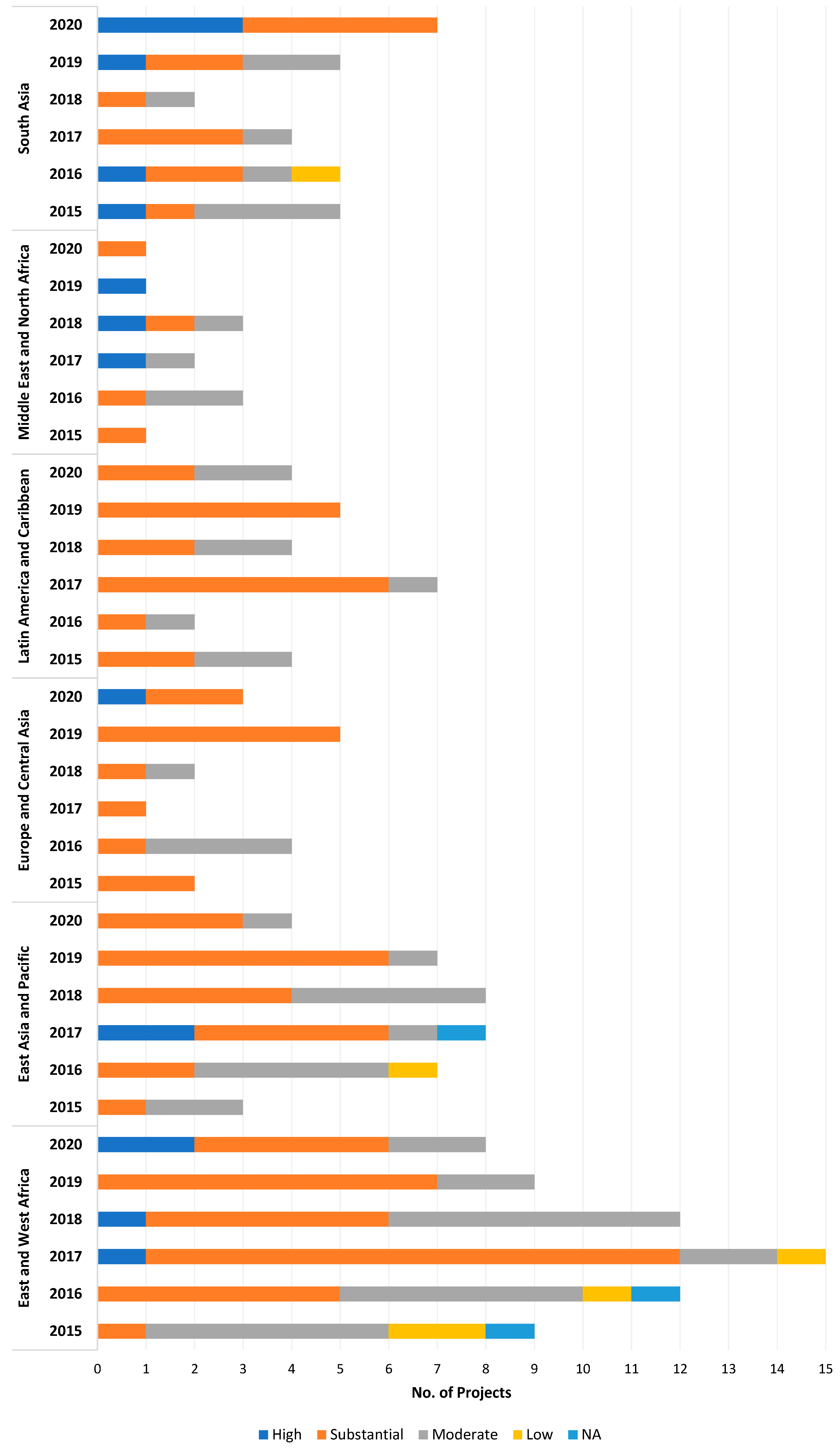

3.2. WSS Project Risks

- The Middle East and North Africa was the only region in which none of the World Bank’s financed projects presented low-rated risks. Moreover, this region was the only one with some of the risks predominantly rated high, namely, the political and governance risk was rated high in 50% of the projects that rated it, and the fiduciary risk was rated high in 45% of the projects that rated it;

- The institutional capacity for implementation and sustainability risk was rated high in several of the projects from East Asia and the Pacific and Latin America and the Caribbean regions (representing 31% and 35%, respectively, of the projects that rated this type of risk in each of the two regions), while in the remaining regions this rate was only attributed to a few of the projects (on average, only 12% of the projects that analyzed this risk rated it high);

- In East and West Africa, all the risks were predominantly rated substantial or moderate. Nonetheless, this region had a higher number of projects that rated the political and governance risk high (11 projects in total, representing 18% of the ratings for this risk in this region). However, percentage-wise, both the previously mentioned Middle East and North Africa region and the South Asia region could be highlighted, since 50% and 29% of the respective regional projects that rated the political and governance risk considered it high;

- In the Europe and Central Asia region, none of the financed projects had the following risks rated high—environmental and social, stakeholders, macroeconomic, and technical design and project. In the case of the macroeconomic and stakeholders’ risks, this was the only region that never rated them high.

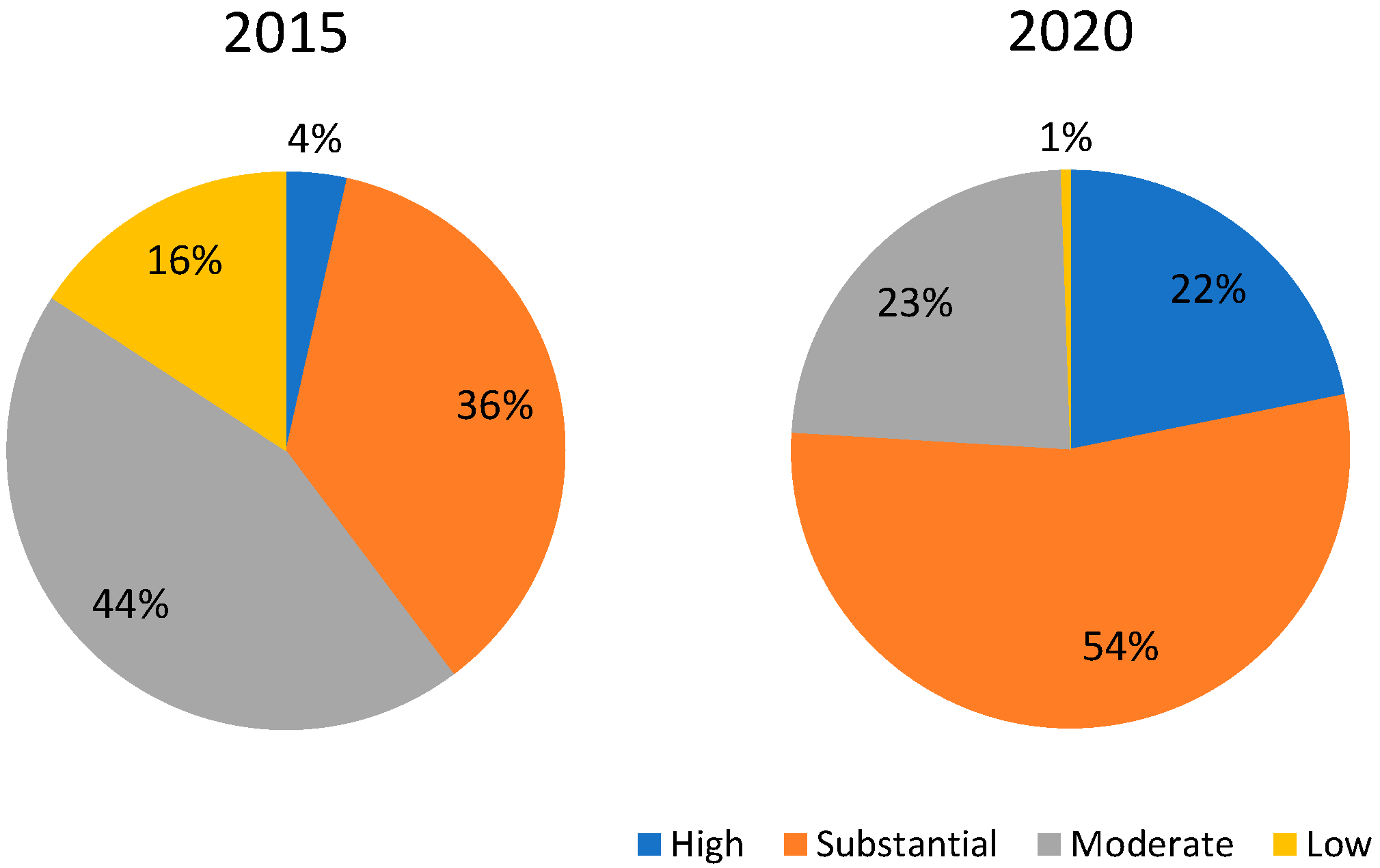

3.3. Historical Risk Appetite

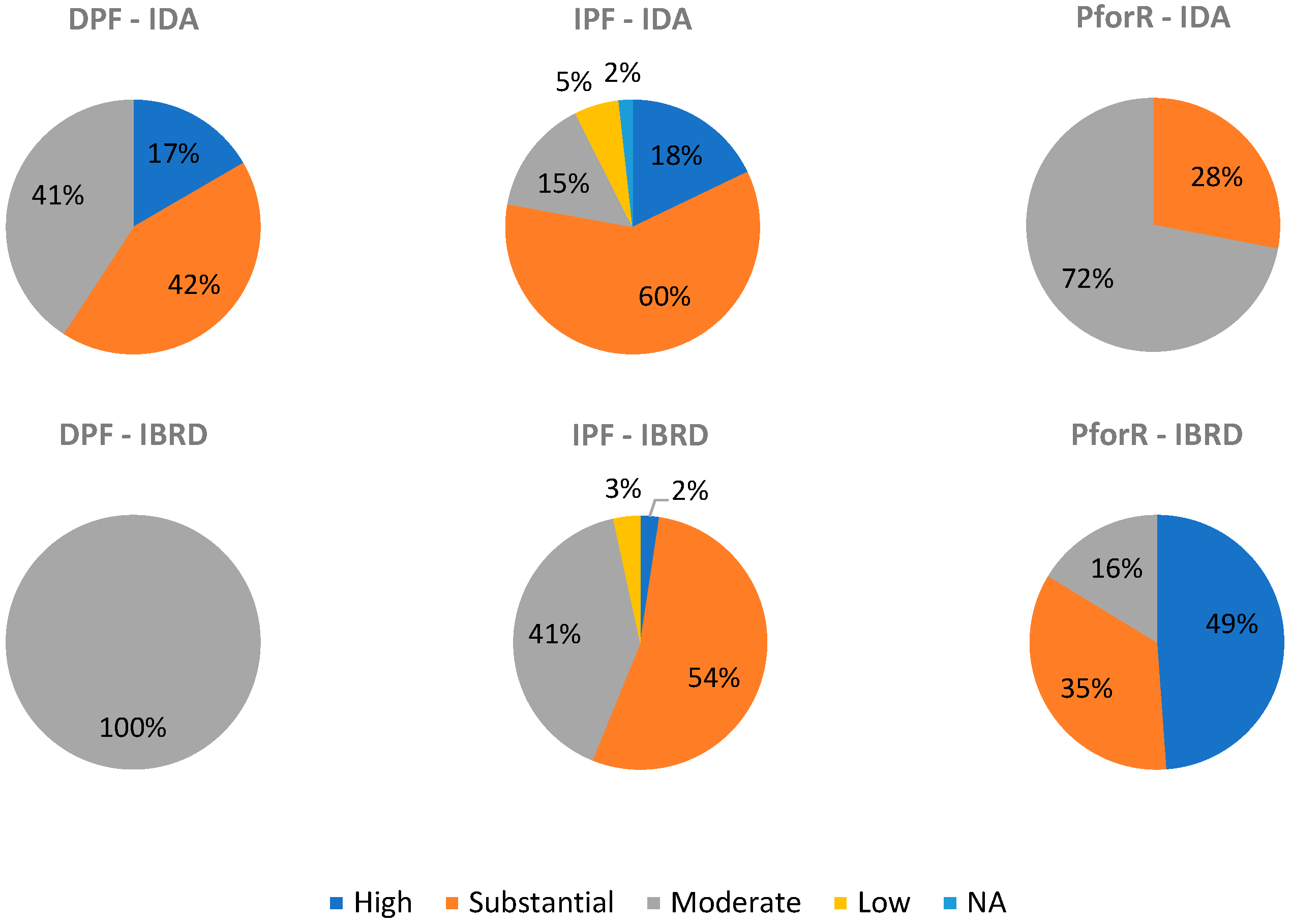

3.4. Average Project Risk Ratings, Lending Instruments, and Commitments

- Most of the DPF commitment went to moderate risk-rated projects (72%), while the remaining commitment financed substantial and high risk-rated projects (20% and 8%, respectively);

- Most of the IPF commitment went to substantial risk-rated projects (57%), while the remaining commitment financed the other groups of risk ratings in the following proportions: moderate—27%, high—10%, low—5%, and NA—1%;

- The PforR commitment was attributed in almost equal proportions to three of the risk-rating groups, respectively, high (36%), substantial (33%), and moderate (31%).

3.5. Final Discussion and Observations

- Wang et al. [47] explored the risk factors of infrastructure PPP projects for sustainable delivery and concluded that key risks can form reaction chains; they divided the risk factors into two specific categories: the ones that have a powerful and independent influence and the ones that are highly vulnerable and easily influenced;

- The credit rating agency, Scope Ratings, developed a General Project Finance Rating Methodology that identified areas of risk, which could result in credit losses to investors exposed to a project, and rated them according to the likelihood and severity of all credit impairment events [48];

- Nepal et al. [49] developed a study on the relative importance of risks, specifically in hydropower projects and project finance in Nepal, using indices to determine the importance of each risk item.

- Different combinations of risk types and respective ratings of the projects that seek financing from the World Bank in the different regions. For example, some developing countries are not able to develop projects with lower risk ratings because of their social–economic situation, while others are in a situation that allows them to better manage project risks. As previously mentioned, thanks to the differences in offered conditions, the first type of country would typically request financing from the IDA, while the latter would tend to work with the IBRD;

- An increased competition for financing in specific regions/countries. Hypothetically, in regions with a large number of requests for financing from the World Bank and a wide variety of projects with different risk ratings, both the IDA and IBRD would be able to choose which to finance based on the project’s intended outcome (e.g., the most socially and environmentally advantageous projects) and on the project’s apparent sustainability and capacity to generate positive results, including sufficient revenues for transfer of capital repayment (i.e., the less risky projects);

- Competitive financing solutions from other development financing institutions:

- In countries or regions that have other development financing institutions providing private financing with fewer barriers to entry (than the solutions offered by the World Bank), the borrowers with projects with the worst risk ratings would, in theory, tend to apply for financing from these other institutions. Thus, these types of situations could have two main impacts—first, the projects looking for financing from the World Bank would, through natural selection, be less risky (with lower risk ratings); second, the World Bank could choose to focus on financing less risky projects since the development of riskier projects would still be guaranteed in these countries;

- In countries or regions that have other development financing institutions providing private financing with the same type of barriers to entry as the World Bank, this could result in the World Bank accepting riskier projects because of the existing competition.

- Regardless of the reasons for the differences observed in each region, the implications for new projects looking to be financed by the World Bank are the same. It could be reasoned, for example, that projects in countries from Latin America and the Caribbean should not only focus on the desired outcome of the project itself but also on reducing their overall risk rating to ensure that it is not rated high (since the World Bank never financed a high-risk project in this region in the analyzed time frame). In addition, and in accordance with the data presented in Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4, Figure A5, Figure A6 and Figure A7, it could also be reasoned that, projects in the Latin America and Caribbean region should avoid having the following types of risks rated high if they want to increase their chances of being financed by the IDA (there are only eight countries eligible for IDA support in this region [50]) or the IBRD: environmental and social, technical design and project, and sector strategies and policies (the World Bank never financed a project in this region with these risks rated high); political and governance (the World Bank only financed one project in this region with this risk rated high); macroeconomic (the World Bank only financed two projects in this region with this risk rated high); fiduciary, and stakeholders (the World Bank only financed three projects in this region with these risks rated high).

4. Concluding Remarks and Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Project ID | Risk Rating Average | Project ID | Risk Rating Average | Project ID | Risk Rating Average | Project ID | Risk Rating Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P170811 | Substantial | P168119 | Substantial | P147158 | Substantial | P154782 | Moderate |

| P169970 | High | P161777 | Substantial | P153814 | Moderate | P159240 | Low |

| P173213 | Substantial | P158124 | Substantial | P164466 | High | P157438 | Moderate |

| P171449 | Substantial | P160672 | Substantial | P156210 | Substantial | P159576 | Low |

| P169179 | Moderate | P165872 | Substantial | P160009 | Substantial | P154255 | High |

| P171620 | Moderate | P160480 | Moderate | P162537 | Low | P156422 | Substantial |

| P174234 | High | P167195 | High | P163846 | Substantial | P157427 | Moderate |

| P171700 | Substantial | P163876 | Substantial | P157782 | Substantial | P156678 | Moderate |

| P174242 | Moderate | P164901 | Substantial | P161566 | Substantial | P152460 | Substantial |

| P173161 | High | P167762 | High | P162840 | Substantial | P130544 | Substantial |

| P169111 | Substantial | P165683 | Substantial | P163194 | Substantial | P147381 | Moderate |

| P172724 | High | P162637 | Substantial | P163468 | Substantial | P149377 | Moderate |

| P173125 | Substantial | P167246 | Moderate | P158807 | Substantial | P150844 | Substantial |

| P171611 | Substantial | P165695 | Substantial | P159426 | Substantial | P155594 | Moderate |

| P168308 | Substantial | P163260 | Substantial | P159956 | High | P152851 | Substantial |

| P169150 | Substantial | P158502 | Moderate | P161630 | Substantial | P155947 | Moderate |

| P171409 | Substantial | P167263 | Substantial | P159049 | NA | P151416 | Moderate |

| P167901 | Substantial | P166063 | Moderate | P161591 | Substantial | P155266 | Substantial |

| P169996 | Substantial | P166597 | Moderate | P156634 | Substantial | P146870 | Moderate |

| P171779 | Substantial | P157043 | Moderate | P155303 | Substantial | P154780 | Low |

| P167328 | Substantial | P161772 | Substantial | P156433 | Substantial | P153251 | High |

| P171877 | Moderate | P165716 | Moderate | P162712 | Substantial | P152693 | Moderate |

| P161432 | High | P163732 | Moderate | P157891 | High | P150475 | Moderate |

| P162263 | High | P164345 | Substantial | P154275 | Substantial | P156559 | Moderate |

| P168025 | Substantial | P163138 | Substantial | P153604 | Substantial | P152623 | Moderate |

| P163957 | Substantial | P164262 | Moderate | P151224 | Substantial | P154680 | Moderate |

| P164389 | Moderate | P160162 | Moderate | P154947 | Substantial | P154112 | Substantial |

| P170595 | Substantial | P167201 | Substantial | P160911 | Moderate | P153113 | Substantial |

| P162938 | Substantial | P161562 | Moderate | P159843 | Moderate | P154729 | Substantial |

| P169830 | Substantial | P165711 | Substantial | P155087 | High | P147827 | Substantial |

| P168233 | Substantial | P163782 | Substantial | P150361 | Substantial | P152801 | Substantial |

| P166697 | Substantial | P158622 | Substantial | P143495 | Substantial | P150351 | Low |

| P171197 | Substantial | P158713 | Moderate | P161559 | Moderate | P154601 | Moderate |

| P165055 | Substantial | P158760 | Moderate | P160014 | Moderate | P152150 | NA |

| P167455 | Substantial | P156125 | Substantial | P156738 | Moderate | P153466 | Moderate |

| P163610 | Substantial | P159870 | Moderate | P154683 | Substantial | P148970 | Substantial |

| P161227 | Substantial | P164186 | Moderate | P156739 | Substantial | P149091 | Moderate |

| P163939 | Moderate | P161915 | Moderate | P160236 | Moderate | P151439 | Substantial |

| P170469 | Substantial | P164845 | Moderate | P161392 | Moderate | P150395 | Moderate |

| P170502 | Moderate | P166075 | Substantial | P160567 | Substantial | P150929 | Substantial |

| P164704 | Substantial | P162094 | High | P156239 | Substantial | P150520 | Moderate |

| P169031 | Substantial | P146206 | Substantial | P153548 | Moderate | P133017 | Moderate |

| P164260 | Substantial | P162245 | High | P154778 | Substantial | P133287 | Moderate |

| P165463 | Moderate | P158146 | Substantial | P133829 | Moderate | P149556 | Low |

| P167794 | Substantial | P163794 | Substantial | P154713 | Substantial | ||

| P168290 | Substantial | P156880 | Substantial | P156253 | NA | ||

| P163734 | Substantial | P149995 | Moderate | P147854 | Moderate |

| Project Risk Rating: High | TOTAL High-IBRD Commitment | TOTAL High-IDA Commitment | ||||||

| IBRD Commitment | IDA Commitment | |||||||

| Regions | DPF | IPF | PforR | DPF | IPF | PforR | ||

| East and West Africa | - | - | - | - | 413,000,000 | - | - | 413,000,000 |

| East Asia and the Pacific | - | - | - | 38,590,000 | 70,000,000 | - | - | 108,590,000 |

| Europe and Central Asia | - | - | - | - | 239,000,000 | - | - | 239,000,000 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Middle East and North Africa | - | 210,000,000 | - | - | 400,000,000 | - | 210,000,000 | 400,000,000 |

| South Asia | - | - | 1,500,000,000 | 100,000,000 | 585,000,000 | - | 1,500,000,000 | 685,000,000 |

| Total | 0 | 210,000,000 | 1,500,000,000 | 138,590,000 | 1,707,000,000 | 0 | 1,710,000,000 | 1,845,590,000 |

| Project Risk Rating: Substantial | TOTAL Substantial-IBRD Commitment | TOTAL Substantial-IDA Commitment | ||||||

| IBRD Commitment | IDA Commitment | |||||||

| Regions | DPF | IPF | PforR | DPF | IPF | PforR | ||

| East and West Africa | - | 895,000,000 | 0 | 350,000,000 | 3,277,300,000 | 300,000,000 | 895,000,000 | 3,927,300,000 |

| East Asia and the Pacific | - | 1,075,000,000 | 400,000,000 | 5,000,000 | 1,054,260,000 | - | 1,475,000,000 | 1,059,260,000 |

| Europe and Central Asia | - | 306,800,000 | - | - | 529,900,000 | - | 306,800,000 | 529,900,000 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | - | 1,590,870,000 | - | - | 165,000,000 | - | 1,590,870,000 | 165,000,000 |

| Middle East and North Africa | - | 108,000,000 | 550,000,000 | - | 10,000,000 | - | 658,000,000 | 10,000,000 |

| South Asia | - | 742,200,000 | 120,000,000 | - | 691,690,000 | - | 862,200,000 | 691,690,000 |

| Total | 0 | 4,717,870,000 | 1,070,000,000 | 355,000,000 | 5,728,150,000 | 300,000,000 | 5,787,870,000 | 6,383,150,000 |

| Project Risk Rating: Moderate | TOTAL Moderate-IBRD Commitment | TOTAL Moderate-IDA Commitment | ||||||

| IBRD Commitment | IDA Commitment | |||||||

| Regions | DPF | IPF | PforR | DPF | IPF | PforR | ||

| East and West Africa | - | 145,500,000 | - | 200,000,000 | 1,112,100,000 | 570,000,000 | 145,500,000 | 1,882,100,000 |

| East Asia and the Pacific | - | 1,643,100,000 | - | 130,000,000 | 130,000,000 | 200,000,000 | 1,643,100,000 | 460,000,000 |

| Europe and Central Asia | - | 143,930,000 | - | - | 36,500,000 | - | 143,930,000 | 36,500,000 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 700,000,000 | 766,600,000 | - | - | 12,800,000 | - | 1,466,600,000 | 12,800,000 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 225,000,000 | 55,000,000 | 500,000,000 | - | - | - | 780,000,000 | - |

| South Asia | 40,000,000 | 795,000,000 | - | 10,000,000 | 110,000,000 | - | 835,000,000 | 120,000,000 |

| Total | 965,000,000 | 3,549,130,000 | 500,000,000 | 340,000,000 | 1,401,400,000 | 770,000,000 | 5,014,130,000 | 2,511,400,000 |

| Project Risk Rating: Low | TOTAL Low-IBRD Commitment | TOTAL Low-IDA Commitment | ||||||

| IBRD Commitment | IDA Commitment | |||||||

| Regions | DPF | IPF | PforR | DPF | IPF | PforR | ||

| East and West Africa | - | - | - | - | 250,000,000 | - | - | 250,000,000 |

| East Asia and the Pacific | - | 300,000,000 | - | - | - | - | 300,000,000 | - |

| Europe and Central Asia | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Middle East and North Africa | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| South Asia | - | - | - | - | 290,000,000 | - | - | 290,000,000 |

| Total | 0 | 300,000,000 | 0 | 0 | 540,000,000 | 0 | 300,000,000 | 540,000,000 |

| Project Risk Rating: NA | TOTAL NA-IBRD Commitment | TOTAL NA-IDA Commitment | ||||||

| IBRD Commitment | IDA Commitment | |||||||

| Regions | DPF | IPF | PforR | DPF | IPF | PforR | ||

| East and West Africa | - | - | - | - | 95,000,000 | - | - | 95,000,000 |

| East Asia and the Pacific | - | - | - | - | 72,520,000 | - | - | 72,520,000 |

| Europe and Central Asia | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Middle East and North Africa | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| South Asia | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 167,520,000 | 0 | 0 | 167,520,000 |

References

- Pories, L.; Fonseca, C.; Delmon, V. Mobilising finance for WASH: Getting the foundations right. Water 2019, 11, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Making Blended Finance Work for Water and Sanitation: Unlocking Commercial Finance for SDG6; OECD Studies on Water; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Machete, I.; Marques, R. Financing the water and sanitation sectors: A hybrid literature review. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, J.A.; Winpenny, J.; Wall, A.W. Water Financing and Governance; TEC Background Papers No. 12; Global Water Partnership/Swedish International Development Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Badu, E.; Edwards, D.J.; Owusu-Manu, D.; Brown, D.M. Barriers to the implementation of innovative financing (IF) of infrastructure. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2012, 17, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafuta, W.; Zuwarimwe, J.; Mwale, M. WASH Financial and social investment dynamics in a conflict-arid district of Jariban in Somalia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta-Veiga, M. Tariff structuring in water and sanitation: Public profiting arrangements on universalization initiative. Water Policy 2021, 23, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEMs. Default Statistics: Private and Sub-Sovereign Lending 2001–2019; Global Emerging Markets Risk Database Consortium, European Investment Bank: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Financing Water, Investing in Sustainable Growth; Policy Perspectives, OECD Environment Policy Paper No. 11; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, C.; Ward, S. Project Risk Management Processes, Techniques and Insights; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfraz, M.; Qun, W.; Hui, L.; Abdullah, M.I. Environmental risk management strategies and the moderating role of corporate social responsibility in project financing decisions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Martek, I.; Hosseini, M.R.; Tamošaitienė, J.; Chen, C. Foreign infrastructure investment in developing countries: A dynamic panel data model of political risk impacts. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2019, 25, 134–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. The Critical Role of Water in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: Synthesis of Knowledge and Recommendations for Effective Framing, Monitoring, and Capacity Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/6185Role%20of%20Water%20in%20SD%20Draft%20Version%20February%202015.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Winpenny, J. Financing Water for All. Report of the World Panel on Financing Water Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 3rd World Water Forum, Kyoto, Japan, 16–23 March 2003; ISBN 92-95017-01-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, J. Regulation and private participation in the water and sanitation sector. Nat. Resour. Forum 1998, 22, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Innovative Financing Mechanisms for the Water Sector; OECD: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dentons. A Guide to Project Finance; Dentons & Co.: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Raftelis, G. Water and Wastewater Finance and Pricing: A Comprehensive Guide, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Gosling, S.N.; Kummu, M.; Flörke, M.; Pfister, S.; Hanasaki, N.; Wada, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, C.; et al. Water scarcity assessments in the past, present, and future. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeckman, J.; Markkanen, S.; Seega, N. Financiers’ perceptions of risk in relation to large hydropower projects. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2022, 2, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, P.; Irwin, T. Allocating Exchange Rate Risk in Private Infrastructure Contracts; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baietti, A.; Raymond, P. Financing Water Supply and Sanitation Investments: Utilizing Risk Mitigation Instruments to Bridge the Financing Gap; Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Board Discussion Paper Series; Paper No. 4; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kehew, R.; Matsukawa, T.; Petersen, J. Local Financing for Sub-Sovereign Infrastructure in Developing Countries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Akintoye, A.; Beck, M.; Hardcastle, C. Public-Private Partnerships: Managing Risks and Opportunities; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, T. Understanding the Challenges for Infrastructure Finance; BIS Working Papers No. 454; Bank for International Settlements: Basel, Switzerland, 2014; ISSN 1682-7678. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison, M.A.; Holt, L.; Berg, S.V. Measuring and mitigating regulatory risk in private infrastructure investment. Electr. J. 2005, 18, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, A.; Mangano, G. Risk and value in privately finance healthcare projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaerts, G. Financing for Water—Water for Financing: A Global Review of Policy and Practice. Sustainability 2019, 11, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Tiong, R.L.; Cheah, C.Y.; Permana, A.; Ehrlich, M. Assessment of Credit Risk in Project Finance. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2008, 134, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. What We Do. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/what-we-do (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- World Bank. Procurement Guidance—A Beginner’s Guide for Borrowers: Procurement under World Bank Investment Project Financing; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Products and Services, Financing Instruments. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/what-we-do/products-and-services/financing-instruments (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Beecher, J. Funding and Financing to Sustain Public Infrastructure: Why Choices Matter—A Primer and Framework for Policy Analysts, Public Officials, and Stakeholders; SSRN, Elsevier: Rochester, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Investing in Infrastructure: Leading Practices in Planning, Funding, and Financing; Deloitte Development LLC: Stamford, CT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CBO. Federal Support for Financing State and Local Transportation and Water Infrastructure; Congressional Budget Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Interim Guidance Note, Systematic Operations Risk-Rating Tool (SORT). Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/SORT_Guidance_Note_11_7_14.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- WHO. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Butler, G.; Pilotto, R.G.; Hong, Y.; Mutambatsere, E. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Water and Sanitation Sector; IFC, World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Emerging Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis and Implication for Water-Related Investments; Background Paper, Roundtable on Financing Water, 6th Meeting; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M. Evaluating the risks of public private partnerships for infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2002, 20, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M. Public-Private Partnerships; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, R.C.; Berg, S. Risks, Contracts, and Private-Sector Participation in Infrastructure. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2011, 137, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A. A new era for public–private partnership (PPPs) in Egypt’s urban water supply projects: Risk assessment and operating model. HBRC J. 2022, 18, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarmeyer, D.; Mody, A. Financing Water and Sanitation Projects: The Unique Risks; Viewpoint: Public Policy for the Private Sector, Note No. 151; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vives, A.; Paris, A.; Benavides, J.; Raymond, P.; Quiroga, D.; Marcus, J. Financial Structuring of Infrastructure Projects in Public-Private Partnerships: An Application to Water Projects; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MIGA. MIGA: Guaranteeing Investments in Water Projects; MIGA Brief; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, J. Exploring the risk factors of infrastructure PPP projects for sustainable delivery: A social network perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellscheidt, T.; Konrad, A. General Project Finance Rating Methodology; Scope SE & Co.: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal, A.; Khanal, V.; Maelah, R. Relative importance of risks in hydropower projects and project finance in Nepal. J. Adv. Acad. Res. 2021, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDA. Borrowing Countries. Available online: https://ida.worldbank.org/en/about/borrowing-countries (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Wang, S.; Dulaimi, M.; Anuria, M. Risk management in framework for construction projects in developing countries. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADB. Urban Water Supply Sector Risk Assessment: Guidance Note; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Chung, J.; Lee, D. Risk perception analysis: Participation in China’s water PPP market. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twagirayezu, G.; Cheng, H.; Nizeyimana, I.; Irumva, O. The Current State and Future Prospects of Water and Sanitation Services in East Africa: The Case of Rwanda. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average Risk Rating | Lending Instrument | No. Projects | IBRD Commitment (USD) | IDA Commitment (USD) | TOTAL (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | DPF | 2 | - | 138,590,000 | 138,590,000 |

| IPF | 13 | 210,000,000 | 1,707,000,000 | 1,917,000,000 | |

| PforR | 1 | 1,500,000,000 | - | 1,500,000,000 | |

| High Total | 16 | 1,710,000,000 | 1,845,590,000 | 3,555,590,000 | |

| Substantial | DPF | 2 | - | 355,000,000 | 355,000,000 |

| IPF | 95 | 4,717,870,000 | 5,728,150,000 | 10,446,020,000 | |

| PforR | 4 | 1,070,000,000 | 300,000,000 | 1,370,000,000 | |

| Substantial Total | 101 | 5,787,870,000 | 6,383,150,000 | 12,171,020,000 | |

| Moderate | DPF | 7 | 965,000,000 | 340,000,000 | 1,305,000,000 |

| IPF | 47 | 3,549,130,000 | 1,401,400,000 | 4,950,530,000 | |

| PforR | 5 | 500,000,000 | 770,000,000 | 1,270,000,000 | |

| Moderate Total | 59 | 5,014,130,000 | 2,511,400,000 | 7,525,530,000 | |

| Low | DPF | 0 | - | - | - |

| IPF | 6 | 300,000,000 | 540,000,000 | 840,000,000 | |

| PforR | 0 | - | - | - | |

| Low Total | 6 | 300,000,000 | 540,000,000 | 840,000,000 | |

| NA (Not Attributed) | DPF | 0 | - | - | - |

| IPF | 3 | - | 167,520,000 | 167,520,000 | |

| PforR | 0 | - | - | - | |

| NA Total | 3 | - | 167,520,000 | 167,520,000 | |

| Total | 185 | 12,812,000,000 | 11,447,660,000 | 24,259,660,000 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Machete, I.F.; Marques, R.C. Project Risks Influence on Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Financing Opportunities. Water 2023, 15, 2295. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15122295

Machete IF, Marques RC. Project Risks Influence on Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Financing Opportunities. Water. 2023; 15(12):2295. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15122295

Chicago/Turabian StyleMachete, Inês Freire, and Rui Cunha Marques. 2023. "Project Risks Influence on Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Financing Opportunities" Water 15, no. 12: 2295. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15122295

APA StyleMachete, I. F., & Marques, R. C. (2023). Project Risks Influence on Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Financing Opportunities. Water, 15(12), 2295. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15122295