1. Introduction

Recreational canyoning is an in-demand activity under the umbrella of so-called outdoor sports, mountain adventure sports, or nature and adventure sports [

1,

2]. Adventure companies used to offer “easy canyons” to less experienced tourists. This activity is relatively safe in low-difficulty canyons under medium to low discharge conditions and stable weather during the late spring and summer. In order to ensure safety, companies offer short-duration activities and promote well-protected canyons, with strong anchors for rappelling, chains that favor beginners’ safe access to delicate areas, and sometimes double anchors that allow two groups to go down at the same time. This “over security” fits with the idea that “the most successful adventure tourism operators are those that minimize the opportunity for loss to as low a level as possible” [

3]. In fact, unexperienced customers of adventure companies look for the expertise and experience of well-trained guides [

4].

However, despite those security measures, accidents happen, mostly due to the wild nature of the environment [

3,

5,

6], human error in managing gear [

7], and poor decisions about environmental conditions (e.g.,: “The company running the trip was severely criticized for ignoring storm warnings on the day of the trip” [

4]). Ströhle et al. [

8] note that about 78.8% of accidents in Austria in 2005–2018 happened under good weather conditions. Brandao et al. [

2] suggest that 80% of accident risk is due to human factors and only 20% to environmental factors. This imbalance towards the human side has traditionally led to companies and guided trainers putting more effort into technical aspects, while ignoring environmental problems. The most well-known factors in this group come from extreme rainfall episodes that trigger flash floods, rockfalls, debris flows, landslides, and human-derived hazards such as dam breaks, dam release of high flows, and fires.

Typical hydrological studies relate the incidence of wildfires to watershed hydrological characteristics: an increase in streambed erosion, debris flow triggering, favoring natural dams, and changes in soil properties such as an increase in hydrophobicity. Most of these well-known factors change the runoff coefficient or the curve number (CN, the proportion of rainfall that promotes runoff). To the best of our knowledge, these important factors have never been taken into account in risk perception analysis related to canyoning.

In this paper, one of the unexpected problems related to a flash flood triggered by previous wildfires is presented. Flash floods can appear even in a well-protected and safe canyon used by companies for beginner activities, as with the flash flood in Los Hoyos canyon (Jerte, Spain).

The Jerte area has a good range of easy canyons to suit tourists. The mountains are less steep and favor open canyons better than other prime zones of canyoning in Spain, such as the Pyrenees, Guara, or Picos de Europa. The granitic nature of bedrock, combined with an old mountain range and forested watersheds, leads to safe canyons where the possibility of “escape” under high water or flood conditions is higher than in other typical canyon areas in Europe. In 2017, a small storm was recorded in the surrounding stations; however, a flash flood killed four people from the same family while they were undertaking a beginner activity with a company. Only two people were rescued safely, the guide and a young boy. At the same time, another group of canyoneers undertaking a guided activity was reached by a flash flood in neighboring Papúos canyon, whose situation has also been studied to complement the information on the event.

The goal of this study is to fill a research gap, because there is no publication that relates the risk of floods and canyoning to the hydrological changes caused by wildfires in a river area. The case study is the first of its kind documented that includes this problem in the context of canyoning. Canyoning is a nature sport practiced by around 400,000 people/year in Spain, both nationals and foreigners. Wildfires are increasing in mountainous areas of the whole Iberian Peninsula and, hence, the risk involved with canyoning is increasing, with several canyons (up to 57 in 2020; see

Figure 1) affected in recent times.

In addition, this study reflects, for the first time, the fact that an accident caused by a flood event is associated with a low return period.

The main objectives of this work are to determine the main reasons for this flash flood accident, to establish its relationship with the previous wildfire, and to determine hidden factors that might have accounted for this extreme sensitivity to environmental changes. Our hypotheses are: (i) the real rainfall was underestimated by rainfall stations due to the mountainous nature of the area, (ii) a previous wildfire provided enough trees to create log dams that failed and broke under small storms, and/or (iii) wildfires have changed the infiltration pattern of the soil, and thus, the runoff exceeded the normal rate for a small storm.

2. Study Area

The Jerte valley, located in the Sistema Central, is one of the main recreational destinations in southwest Spain and hosts outdoor activities such as hiking, mountain biking, canyoning, and kayaking. Los Hoyos canyon is a tributary of Papúos canyon (

Figure 2), located in Jerte village (southwest Spain). It is a mountain river with a mixed substrate composed of bedrock and large sediments (mainly boulders), with steep slopes in its basin (

Figure 3) that reach 0.18 m m

−1 in Los Hoyos canyon and 0.20 m m

−1 in Papúos canyon (see

Table 1). The geological substrate is mainly made up of granite-type materials, underlying shallow soils that may be grouped as Entisols [

9], with little evidence of the development of pedogenic horizons. Elevations from the upper watershed to the lower valley are from 1900 to 600 m.

The mean annual precipitation is 1225 mm year

−1, as is typical for mountain areas, and occurs mostly during the winter months, making July (the month of the fatal event) a typical low-precipitation month. Maximum daily rainfall (

Table 1) is 69 mm (2-year return period) and 214 mm (500-year return period) in Los Hoyos Canyon, with similar numbers for Papúos canyon. Stream flow is dominated by winter runoff events that produce an annual peak in the winter months. The Q2/Q500 ratio (which measures the degree of variability) is 10/57 (Hoyos) and 14/79 (Papúos). Land cover is similar in both canyons: mostly pastures in the upper basin, pine and oak forest in the medium basin, and cherry orchards in the lower basin. There are patches of old wildfires in Papúos. The total area of the watershed affected by the 2017 wildfire is 74% in Hoyos and 42% in Papúos.

3. Methods

The Los Hoyos and Papúos streams were inspected along their whole length using proper canyoneering techniques during the several days after the flash flood. An immediate field survey was made after the fatal event to collect information about high water marks (HWM, i.e., flotsam; the floating elements left by the flash flood) and other flood markers such as vegetation bent by the river flow. During the inspection of both rivers, the presence of favorable sites for calculating the flow more accurately were identified, searching for evidence of the type of flooding: ordinary flood, hyperconcentrated, or debris flow, and specific problems such as a log dam.

Precipitation data were obtained from the Spanish weather forecasting agency (AEMET). Spatial information (slope map, distances, concentration times, land cover) was calculated using ArcGIS (ESRI: Redlands, CA, USA) software. A first simple hydrological approach (rational method) was used to calculate the discharge related to return period intervals. Furthermore, a full hydrological model simulation was created in order to calculate the maximum discharge of the 2017 event by means of HEC-HMS (CEIWR-HEC: Davis, CA, USA) software. Comparative floodwater height evidence along the Los Hoyos and Papúos streams was collected, using the method of critical point calculation discharge (

Figure 4A). The maximum water height was used in hydraulic calculations to obtain the approximate discharge.

The basin model used in the HEC-HMS software was derived from a 5 m Digital Elevation Model (DEM). Disaggregation was based on the spatial distribution of the physiographic factors that determine a homogenous hydrologic response (i.e., lithology, soils, cover type, hydrologic conditions, and slope), which divide the Hoyos and Papúos basins into 3 and 11 sub-basins, respectively. The use of simulation methods for the various processes involved was based on the information available for the basin (no flow data are available for the Hoyos and Papúos basins). The use of the SCS-CN loss method, which is well developed and widely accepted in the USA and other countries [

10,

11,

12], was based on the availability of data sources for each necessary parameter (surface slope, soil hydrological conditions, and land use); and also on the possibility for conducting fieldwork to test and adjust the values that were previously obtained by photointerpretation.

The absence of rainfall and flow data associated with the same event reduces the availability of transformation methods in the HEC-HMS environment to only two options, so the runoff hydrograph was obtained using the Clark unit hydrograph [

13] with estimated concentration time (Tc) and storage coefficients. The time of concentration was derived using the Témez formula, which depends on the length of the main channel for each sub-basin and its slope [

14]. The storage coefficient was calculated, assuming that it represents 0.6 Tc. The Muskingum–Cunge method was implemented for flood wave routing [

15], due to the absence of observed flow data for the rainfall event. The Muskingum–Cunge parameters were calculated based on the flow and channel characteristics. The eight-point method was selected to define the stream cross-section, and the surface roughness (Manning’s

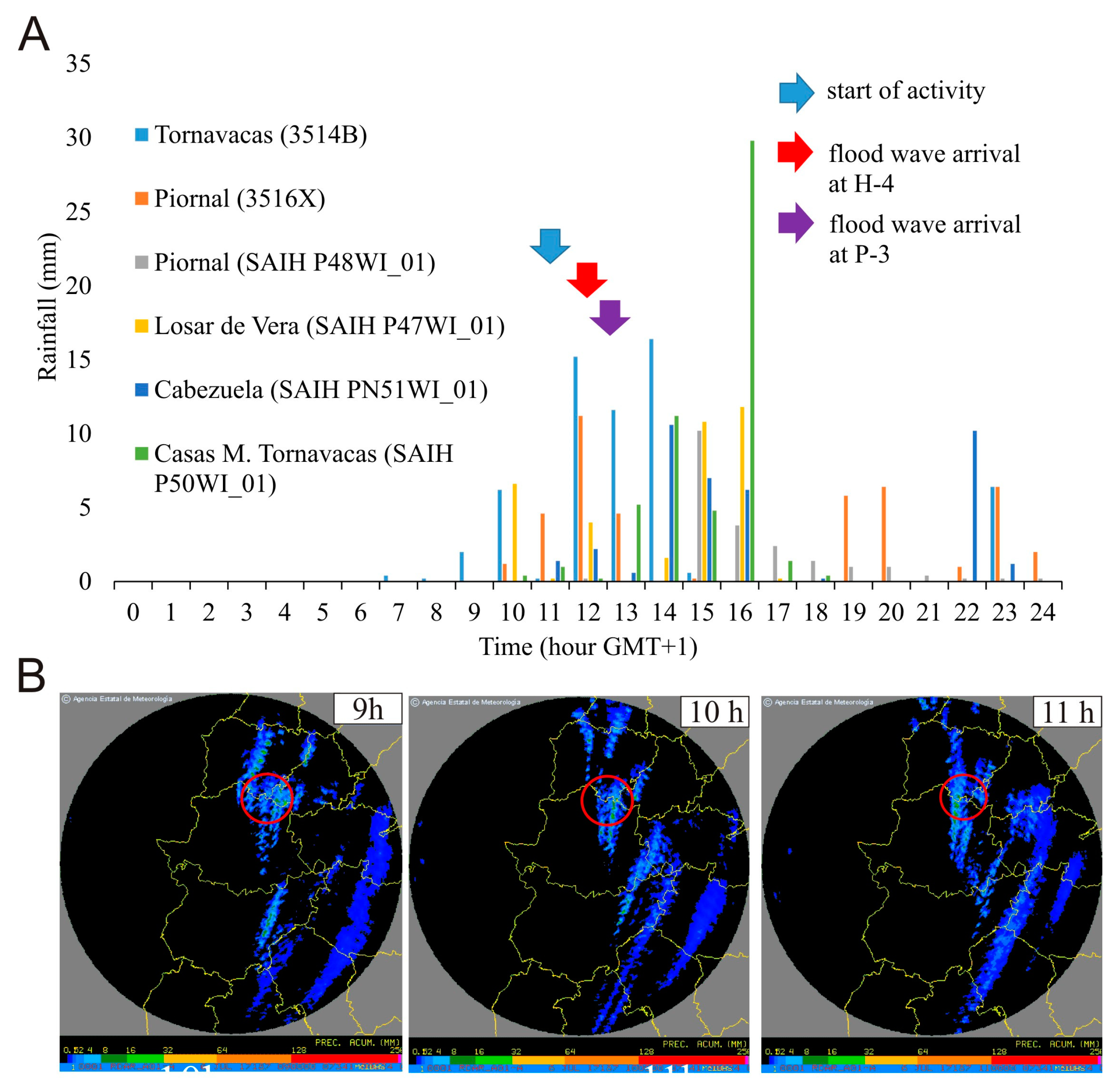

n value) was defined for each channel and banks. Rainfall intensity data for flash flood events were derived from radar images provided by AEMET, so the closest precipitation gauges did not record precipitation prior to the flash flood. The absence of a precipitation record was due to the existence of a rainfall–elevation gradient in the basin, so the rainfall at lower elevations (where gage stations are located) at the time of the event, but not in upper parts of the basin, was negligible.

Wildfire information (fire extent, characteristics) was obtained from the Forest Service of Environmental Agency of Junta de Extremadura (Spain).

Soil sampling was performed following a randomized systematic design in two different areas: burned and undamaged areas. Nine infiltration tests were done per area using the single ring method (

Figure 4B, ref. [

16]). The texture and moisture content of the soil affect the rate of infiltration; therefore, nine composite topsoil samples (0 to 10 cm depth) were collected using a spade after removing the surface debris from each area in order to study the soil texture. The particle size was determined by the hydrometer method [

17], considering sand (0.5–2 mm), silt (0.002–0.5 mm), and clay (<0.002 mm). Additionally, nine 100-cm

3 cylinders per area were used to remove undisturbed soil core samples. Samples were dried (150 °C until constant weight) in an oven and weighed [

18] to obtain the bulk density and soil moisture at the moment of sampling.

5. Hydrology of the Hoyos and Papúos Rivers

Low to moderate rain drives a similar return period in discharge unless changes in basin characteristics disturb ordinary behavior. The peak flow values for different return periods were estimated for Q2, Q25, Q100, and Q500 years, which are the typical intervals used in water resources planning and civil protection planning in Spain. The results of the rational method show theoretical discharges of Q2 of 10 and 14 m

3 s

−1 for Hoyos and Papúos, respectively. The peak flows derived from the rational method come from the application CauMAX [

20], where a runoff coefficient for unburned conditions were used; the runoff coefficient value for Hoyos and Papuos was 0.28. Furthermore, the initial abstraction values were 27.24 and 24.93 mm for Hoyos and Papuos, respectively. No infiltration is considered via the CauMAX application. This theoretical value should correspond to the real value if there is a correspondence between rainfall and flow.

Two hydrological analyses were conducted in order to obtain the real discharge of the 2017 flash flood and test it against the theoretical discharge of Q2. The first was performed using the HEC-HMS program (where the pre- and post-fire situations were assessed for CN value change), and the second involved an estimation of discharge by means of HWM—mainly flotsam associated with hydraulic drops. The results of both analyses and a comparison with the theoretical data are given in

Table 4.

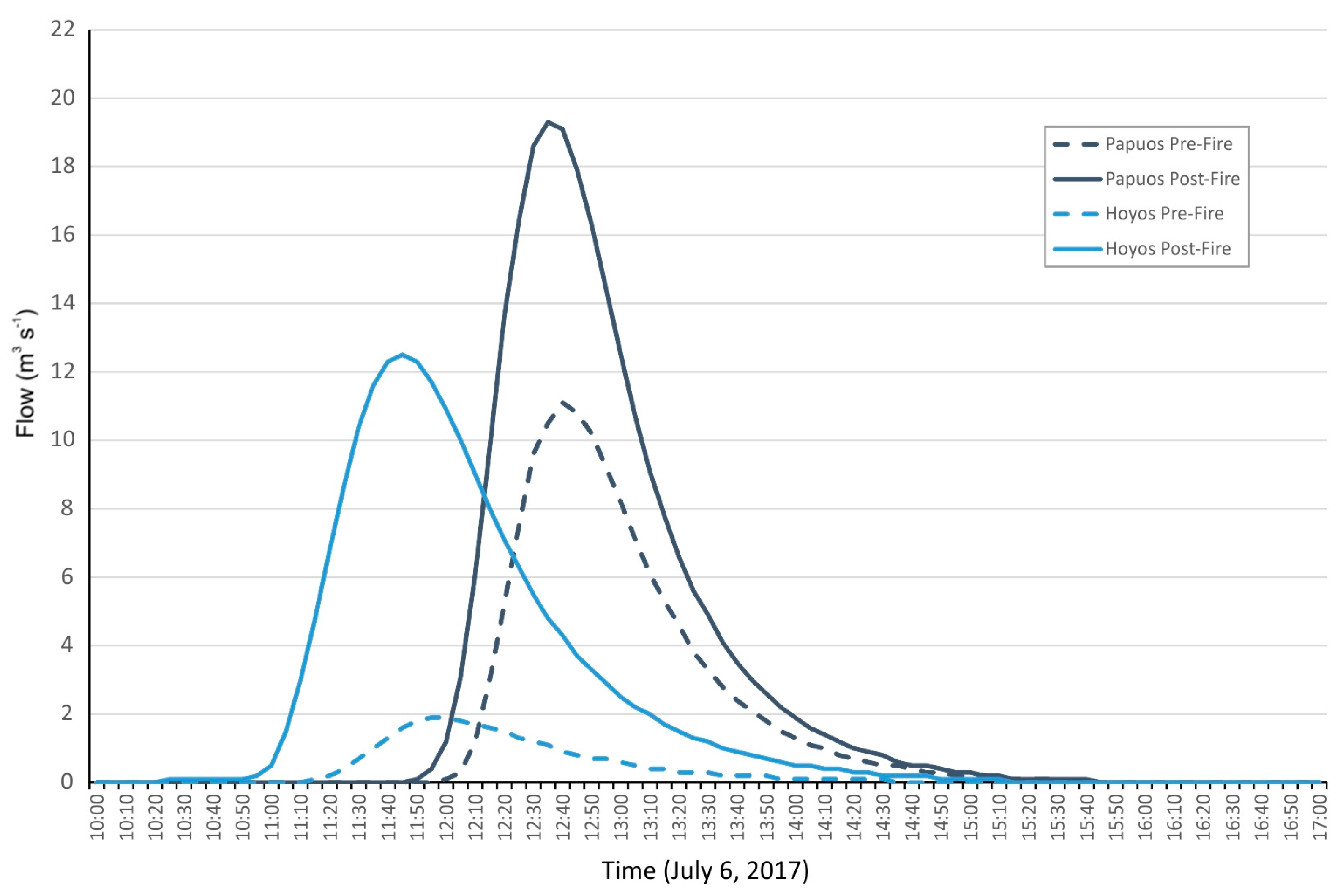

The HEC-HMS model for the Hoyos basin divides it into three sub-basins, which were not affected to the same extent by burning. Estimated pre- and post-fired CN mean values for the basin increased from 65.36 to 82.56 (

Table 4), respectively, although the changes due to fire were more intensive in the two upper sub-basins (with CN mean value changes from 62 to 84). The CN values for burned areas follow the proposed values of Yochum and Norman [

21]. These changes in CN values give rise to changes in outflow rates, so the peak flow value in the pre-fire scenarios does not reach a value of 2 m

3 s

−1, while in the post-fire scenario this value increased to 12.5 m

3 s

−1 (an increase of 658%; see

Figure 7). In the Papúos basin model, up to 11 sub-basins were defined, and the CN mean values for the whole basin changed from 71.18 to 78.08 when the post-fire conditions were considered. As for the Hoyos basin, there were major changes in some of the sub-basins in terms of the mean CN value (with some cases in which the CN value rose from 59 to 79). For the Papúos basin, the increase in the peak flow value was not as pronounced as in the Hoyos basin, with an outflow rate for the pre-fire scenario of 11.1 m

3 s

−1, while this value rose to 19.3 m

3 s

−1 for the post-fire scenario (an increase of 174%; see

Figure 7). The results obtained with the HEC-HMS model showed that the effects of the fire not only caused an increase in the peak flow value associated with the 2017 rainfall event, but there was also an increase in flow velocity, directly associated with the increase in peak flow. Thus, the maximum flow velocities estimated for the study area in the Hoyos basin increased from 1.9 m s

−1 to 3.75 m s

−1—they practically doubled. In the case of the Papúos basin, the variations were not so important, and in both cases, the flow velocities reached were significant. In this case, the pre-fire situation showed maximum flow velocity values of 5 m s

−1; in the case of the post-fire situation, this value increased to over 6 m s

−1.

7. Discussion: Lessons for the Safe Practice of Recreational Canyoning

Considering that the soil type, altitude, aspect, texture, and moisture were similar between burned and undamaged soils, differences in soil infiltration may be attributed to the effects of fire, which were maintained over time [

22], as this experiment was conducted two years after the wildfire.

It is well known that, after wildfires, the ability of soils to facilitate water infiltration is affected at the catchment scale due to the dramatic change in vegetation cover [

23] and soil sealing, which is exacerbated by soil compaction due to water impact, and pore occlusion due to significant amounts of ash covering the soil surface [

24,

25]. In addition, the soil wettability is reduced [

26] and high temperatures produce water-repellent organic compounds [

27]. All these processes lead to the development of water repellency after wildfires, especially if soils were previously hydrophobic due to remains from dominant vegetation with hydrophobic leaves [

28,

29], as was the case in the pine and oak forests of the study area.

The links between these processes and overland flows during rainstorm events have been frequently described in the literature. Some of the main conclusions have been in evidence in this event, such as the important role of ashes in post-fire sediment amplifying erosion, as pointed out by Gabet and Sternberg [

30], mentioned in several reports (i.e., [

31]), and clearly observed in pictures (

Figure 5D). Previous rainfall may have played a key role in these hydrophobic conditions as, if the ash is wet, infiltration capacity is reduced [

29]. The hydrophobicity may be diminished in the few months after the wildfire [

32]. However, Dyrness [

33] suggests that hydrophobic layers can persist for up to six years. Our soil analysis confirmed this, with clear differences seen in soil infiltration two years after the wildfire, which could be attributed to hydrophobicity. Furthermore, the fatal event occurred only a few months after the fire and in the absence of previous rainfall events, hence the strong hydrologic response. In our field research in 2019, the accumulation of runoff in the first 2–3 min of the storm could be explained by the strong hydrophobic response, and could have been greater during the event in 2017.

Looking at the hydrological results, the rainfall event does not exceed the two-year return period, and the expected discharge might be less than 10 m

3 s

−1 (Hoyos) and 14 m

3 s

−1 (Papúos). Considering “normal” soil conditions and land use in the basin, the rainfall–runoff transformation calculated with HEC-HMS revealed peak flow values of 1.9 m

3 s

−1 (Hoyos) and 11.1 m

3 s

−1 (Papúos). However, both methods uncovered higher discharges, of about 8–12 m

3 s

−1 (Hoyos) and 8–19 m

3 s

−1 (Papúos). The hydrological model takes into account changes in CN, as suggested by Yochum and Norman [

21], and shows for the Jerte event a dramatic increase of ~660% in flow discharge in Hoyos and 175% in Papúos; this explains how a small storm could have drastic consequences for canyoning. These results are consistent with data recorded during fieldwork that show similar discharges obtained from floating elements and other HWM.

From a hydrological point of view, the methodologies and results presented here are in agreement with previous assessments. Changes in soil conditions due to fire cause an increase in CN values and, in direct relation to the above, result in an increase in peak flow values during flooding events. CN values for the post-fire situation trend upward along with the fire severity (e.g., [

34,

35,

36]), or by substituting the pre-fire land cover with other types that are more likely to be representative of the post-fire conditions (e.g., [

37,

38]). Only in a few cases (e.g., [

39]) is there sufficient information to fuel an analysis of hydrological changes in the rainfall–runoff process after the occurrence of wildfires. In our case, the definition of CN values after fire could be related to the approach linked to the substitution of pre-fire land cover, although the increase in CN values was compatible with the hypothesis that CN values increase with fire severity. Furthermore, the differences in CN mean values pre- and post-fire are coherent with the ranges of Soulis [

39], and with the results of the infiltration field test.

All these changes in CN give rise to variations in the value of the peak flow, increasing its value significantly as well as slightly modifying the time at which the peak of the hydrograph occurs (acceleration of the flood wave). In his assessment in Attica (Greece), Soulis [

39] noted an increase in peak flow by more than 11.8-fold, although this must be considered alongside the percentage of basin burned and the severity of the fire. Our results do not indicate changes of that magnitude, but the peak flow at the Hoyos basin increased by a factor of more than six (and two for the Papúos basin). These results are coherent with the extension of burnt soil into the two basins: higher for the Hoyos basin (78% of the basin fired) and lower for the Papúos basin (where only 38% of the basin was affected by fire). As wildfire changes the surface roughness as well (by removing vegetation), the Manning’s

n-value used in the HEC-HMS model for channels and banks decreases, and, consequently, there is an acceleration of the flood wave due to the lower roughness of the terrain. The effect of this change was more evident in the Hoyos basin as well, where the peak flow for the post-fire situation was 15 min earlier, while in the Papúos basin, the peak flow pre- and post-fire fell within the same 5 min interval.

Finally, the effect of wildfire on the hydrological behavior of the Hoyos and Papúos basins was also observed in the form of an increase in flow velocity. The increase in flow velocity was especially significant in the Hoyos watershed, where the maximum flow velocity almost doubled when we consider the effects of the fire on the watershed. In this basin, flow velocities reached values that are clearly dangerous for human stability (even at low flow depths). In the case of the Papúos basin, even if the flow velocity value increased, the differences were not so great, and in both situations (pre- and post-fire), the velocity values were dangerous. It is true that the HEC-HMS model considers the Saint Venant equations for one-dimensional flows, which may reduce the reliability of the values obtained, but it is no less true that, in the type of channels studied (channels embedded in bedrock rivers), the water flow can be considered one-dimensional.

The increase in flow velocity was especially important in Hoyos canyon, where the fatal accident occurred, as opposed to Papúos, which is more conducive to accidents, as it is a larger waterfall with a wider, slippery rocky substrate. Another hydrological factor that influenced the fatal accident was the increase in the tractive and buoyant forces of the flow due to the ash concentration [

30]; this might have been responsible for the water dragging the canyoneers along with a high velocity of flow.

8. Management Implications

Flash floods are well known for their dangerous nature within canyons. Several fatal events have been reported in recent times (ABC News:

https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/spaniards-dead-missing-swiss-canyoning-accident-72345296, accessed on 9 March 2021, BBC News:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-45043778, accessed on 9 March 2021). Despite this, little is known about flash floods in the communities based in the areas studied. A lack of information about accidents in canyoning, together with an absence of central reporting and management by any official agency, obscure the magnitude of the situation [

3,

40,

41]. Hydrological and meteorological information needs appropriate analysis. As Morgan [

42] reports, “personnel in the industry are predominantly young with a desire for excitement and adventure, this severely affects safety judgements and assessments of client capability.” The guide during the Jerte event was young and had little experience, including with weather forecast interpretation.

Some interesting changes in management would be useful, such as: (1) understanding how a low-discharge event can be enough to kill canyoneers, (2) understanding that the potential damage capacity increases with the suddenness of an event, (3) having an exit route protocol in place prior to flash flood situations, (4) ensuring that not only is gear checked and weather forecasted, but knowledge of basin changes is considered as part of the safety procedures for typical guiding, and (5) understanding that all changes leading to increased flash flooding in a fluvial basin involve faster flows, increased peak discharge, increased sediment and flow viscosity, and reduced concentration time, and hence, reduced evacuation time.

9. Conclusions

Although the vast majority of accidents associated with the recreational use of river canyons are due to human factors (such as a lack of expertise or experience on the part of the guides), environmental factors (such as extreme weather events) cannot be underestimated in this type of situation. Thus, the present work shows a clear example of the above, in which the prior occurrence of a wildfire caused a series of modifications in the hydrological response of a river basin, which finally triggered the occurrence of an accident (due to a flash flood) with fatal consequences (four people died while practicing canyoning).

The present study analyzes the disturbances in hydrological behavior that occurred in the watersheds of the Hoyos and Papúos streams after a wildfire, and assesses how these alterations in hydrological characteristics (loss of infiltration capacity of the soils, increase in the production of solids, reduction in the surface roughness of the terrain due to the loss of vegetation, etc.) gave rise to a significant increase in the production of surface runoff associated with a moderate rainfall event.

The hydrological simulation of the rainfall event that occurred on 6 July 2017 verified that both the peak flow values of the generated hydrograph and the flow velocities increased due to the terrain alteration caused by the fire (whose first and most important alteration was manifested in a clear increase in the hydrophobicity of the soil, sharply decreasing its infiltration capacity; this natural process is usually incorporated into hydrological models as a clear increase in the CN value associated with the burned part of the basins). Thus, the peak flow values increased more than six-fold (650%) in the Hoyos basin, and two-fold (175%) in the Papúos basin.

Under these conditions, the accident that occurred on 6 July 2017 should be included among cases in which the accident is conditioned by environmental factors, and exceeds the experience and expertise of the canyoning guides. The results obtained in the present work highlight the need to analyze in detail the conditions of canyoning areas (with the aim of increasing safety) where fires have occurred in some part of the river basin. As shown in

Figure 1, tens of canyons have been affected over the last two decades, and the potential for new wildfires to affect canyoneers is increasing as the popularity of this activity grows.