Abstract

Rivers are complex biophysical systems, constantly adjusting to a suite of changing governing conditions, including vegetation cover within their basins. This review seeks to: (i) highlight the crucial role that vegetation’s influence on the efficiency of clastic material fluxes (geomorphic connectivity) plays in defining mountain fluvial landscape’s behavior; and (ii) identify key challenges which hinder progress in the understanding of this subject. To this end, a selective literature review is carried out to illustrate the pervasiveness of the plants’ effects on geomorphic fluxes within channel networks (longitudinal connectivity), as well as between channels and the broader landscape (lateral connectivity). Taken together, the reviewed evidence lends support to the thesis that vegetation-connectivity linkages play a central role in regulating geomorphic behavior of mountain fluvial systems. The manuscript is concluded by a brief discussion of the need for the integration of mechanistic research into the local feedbacks between plants and sediment fluxes with basin-scale research that considers emergent phenomena.

1. Introduction

Rivers are complex and dynamic systems, constantly adjusting to a suite of changing governing conditions, which include the characteristics of the biophysical landscape within which they are embedded. From a geomorphic point of view, these adjustments are achieved through changes in sediment transport rates, which are, in turn, manifested in evolving channel morphology [1,2]. Because of the role of clastic material flux as the currency of river and landscape change, sediment yield and sedimentary archives have long been used as indicators of geomorphic behavior, for example, responses to disturbances and environmental change [3,4,5]. A long-standing recognition of the role that sediment routing plays in modifying such environmental signals [6,7] is reflected in a recent surge of interest in the concept of geomorphic connectivity (or sediment connectivity) (Figure 1). A range of definitions have been proposed but, essentially, the concept of connectivity is concerned with connections, or interdependencies, between parts of the landscape that are facilitated by sediment transfer (interested readers are referred to several excellent reviews on this subject: [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]). In this review, I refer to geomorphic (sediment) connectivity in the sense that is perhaps closest to the definition articulated by Heckmann et al. [12]: “we define (…) sediment connectivity as the degree to which a system facilitates the transfer of (…) sediment through itself, through coupling relationships between its components. In this view, connectivity becomes an emergent property of the system state, reflecting the continuity and strength of (…) sediment pathways at a given point in time. Structural connectivity represents the spatial configuration of system components; functional connectivity is inferred from the actual transfer of (…) sediment.” This definition can, conveniently, be applied at any spatial scale, including an assemblage of adjacent landforms or the entire drainage basin (e.g., in the context of sediment yield). Even though the concept can be adopted for geomorphic, hydrological, as well as ecological fluxes [11,15] the focus in this case will be primarily on sediment.

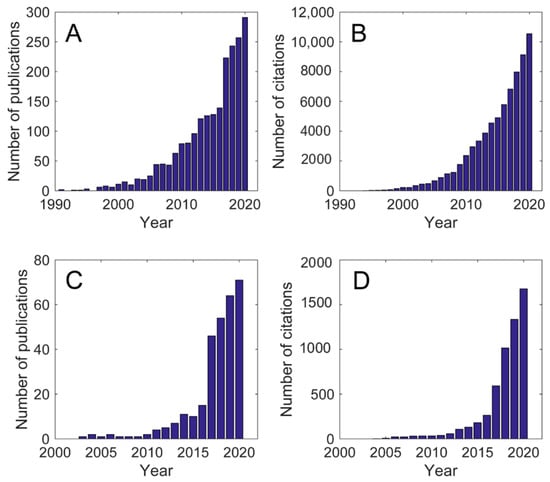

Figure 1.

A summary showing an increasing interest in the concept of landscape system connectivity during the last decades (Web of Science Core Collection search was conducted on the title, abstract and keywords, within the timespan of 1900–2020). (A) number of publications focusing on connectivity: this search considers landscape connectivity, a term often used in ecology (search terms “landscape connectivity” OR “sediment connectivity” OR “geomorphic connectivity”); (B) number of citations (same search terms as in A); (C) number of publications specifically focusing on geomorphology/geosciences (search terms “sediment connectivity” OR “geomorphic connectivity”); (D) number of citations (same search terms as in (C)).

The appeal of the connectivity concept lies partly in this versatility, but also in the ease with which it can be related to the sensitivity of geomorphic systems. In the simplest terms, geomorphic sensitivity can be understood as a measure of the relative magnitude or severity of the system’s response to a given disturbance [16,17], although sometimes it is also expressed in terms of probability of an “appreciable change” [18,19,20]. Because connectivity can be thought as representing information flow across the landscape, it also facilitates the propagation of disturbances within the geomorphic system, thereby contributing to landscape’s sensitivity [21]. The fact that an explicit consideration of the spatial configuration and relationships is at the very heart of the connectivity framework makes this approach well-suited for identifying those parts of the landscape which may play a critical role in the overall sensitivity of the system [22]. Thus, when combined, these two concepts provide a useful toolkit for the analysis of geomorphic systems’ behavior and its variability [16,20].

Importantly, geomorphic connectivity also provides a convenient framework to consider the role of vegetation, as one of the above-mentioned biophysical controls on fluvial systems. For example, the stabilizing and destabilizing influences of vegetation on sediment can be thought as reducing and increasing connectivity, respectively. These effects of vegetation are highly relevant from the perspective of sensitivity because they can contribute to nonlinear responses of geomorphic systems [23]. It is useful to highlight at the outset that the influence of vegetation on landscape processes extends beyond the lifetime of a plant: downed dead wood (often referred to as coarse woody debris or large wood) may continue to be a strong control on fluxes of water and sediment [24,25,26,27,28]. Accordingly, in the following discussion, I will use the term “vegetation” in a broad sense that includes large wood. Generally speaking, the effect of vegetation on erosional processes and the influence of geomorphic processes on ecosystems, have long been acknowledged in geomorphology [29,30,31,32]. However, a more nuanced appreciation of the reciprocal interactions between geomorphic processes and living organisms has begun to rapidly develop in the last three decades [23,24,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. This increased interest manifested itself in the formation of a new sub-discipline, referred to as biogeomorphology or ecogeomorphology, although there has been some confusion and debate as to the equivalence of these and other similar terms [41]. Despite the considerable progress achieved in biogeomorphic research, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the highly complex, multi-faceted vegetation-geomorphology feedbacks [23,26,42,43,44,45].

This fragmentary understanding of the intricate relationships between vegetation and geomorphic connectivity substantially hampers our ability to comprehend the functioning of the biophysical landscape system, including its sensitivity to past and future environmental change [46]. Rivers and landscapes adjust to variations in climate, which may occur over multiple time scales [5,47,48]. Fluctuation in precipitation and temperature can in turn have a direct impact on geomorphic processes, for example, by determining runoff; however, they can also exert indirect influence, by regulating geomorphic activity through vegetation dynamics, which responds to changing climatic variables [49,50] (Figure 2). In addition, humans have become an increasingly influential driver of the contemporary environmental change, profoundly affecting vegetation and, thus, geomorphic processes through our collective impact on climate system [51] and land use change [52]. On the other hand, an increasing recognition of the extent, magnitude, as well as ecological and societal implications of the anthropogenic disturbances and environmental degradation has sparked growing efforts to reverse this environmental damage through restoration [53,54,55,56] (Figure 2). Depending on the nature of the environmental impacts at hand and defined goals, such efforts may often involve restoration of the vegetation cover, for example, riparian forests [54,57].

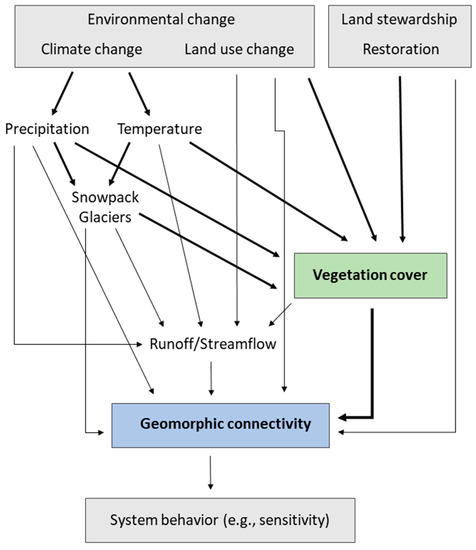

Figure 2.

A simplified conceptual model illustrating the role of vegetation in mediating various effects of environmental change and land stewardship efforts (e.g., restoration) on geomorphic connectivity and, ultimately, the overall behavior of the fluvial landscape system. The pathways mediated by vegetation are represented by bold arrows.

In this paper, I seek to demonstrate the crucial role of vegetation in defining geomorphic connectivity in mountain fluvial systems, and to identify some major challenges for future research. My primary intention here is to merely highlight an important research area which, in my view, deserves more interdisciplinary attention, rather than focus on quantitative estimates of the magnitude of the biotic effects. To this end, I begin with a selective review of diverse mechanisms through which vegetation influences geomorphic connectivity. It is impossible to provide an exhaustive discussion of the reciprocal biogeomorphic interactions in such a short contribution. Instead, my objective is to briefly illustrate the ubiquitous nature of biotic controls in mountain fluvial landscapes. This discussion is meant to complement more detailed, environment-specific reviews that focus on hillslope or riparian processes [38,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. In the second part of the paper, I move on to overview some research gaps and challenges with respect to the links between vegetation and geomorphic connectivity in the context of mountain fluvial system’s behavior. In doing so, I identify and outline a research approach which seems suitable for addressing these challenges.

2. Vegetation and Geomorphic Connectivity

In this section, I aim to highlight the effects of vegetation on geomorphic connectivity. In order to organize the discussion, I divide it according to two types of connectivity, longitudinal and lateral, often distinguished in the literature of this subject along with vertical connectivity [8,11,22] (Figure 3). Definitions used here are those proposed by Fryirs et al. [66]: longitudinal connectivity refers to sediment transfer within the channel network, while lateral connectivity refers to sediment exchanges between the channels and the broader landscape, including valley floor (e.g., floodplain) and the adjacent hillslopes. In terms of valley floor processes, I further distinguish: (i) bank erosion and retreat, which leads to gradual lateral migration of the channel; and (ii) avulsions, which are understood here broadly, as abrupt shifts in the lateral position of a channel, regardless of whether it is partial (only a portion of flow rerouted) or full, and whether it involves the formation of a new channel or annexation of a pre-existing one (see [67] for more information on these distinctions).

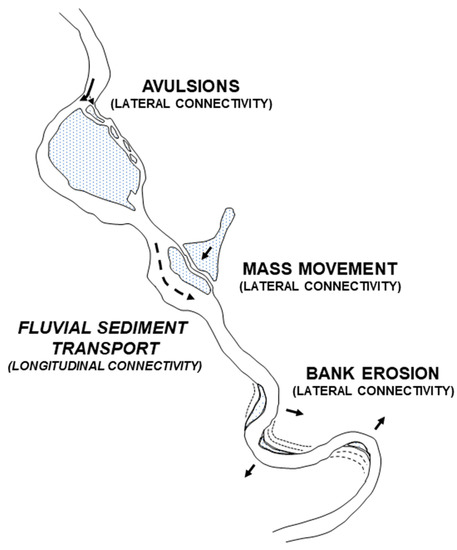

Figure 3.

Geomorphic connectivity types, as defined in this review.

2.1. Lateral Connectivity

2.1.1. Bank Erosion

Vegetation exerts an important influence on lateral geomorphic connectivity by regulating bank stability and erosion rates. The term “bank erosion” is used here in a broad sense and includes all the processes that may lead to bank retreat, for example, removal of individual particles by hydraulic action as well as mass bank failure [68,69,70]. These fundamental fluvial processes have been viewed both as a concern (e.g., as a natural hazard) and as desirable geomorphic phenomena that supply sediment and organic material to channel networks [71,72]. As a result, the effects of riparian vegetation on bank stability have been a subject of substantial interest for a long time [69,73,74,75,76,77,78] and it is, without a doubt, among the most thoroughly researched links between vegetation and fluvial processes. However, because of the sheer complexity of these biophysical interactions and the importance of variable, site-specific factors, they remain difficult to model mechanistically [76,77]. The biotic control on bank erosion is exerted through hydrological and mechanical processes [76,79]. Although, typically, the net outcome of these mechanism is to stabilize banks, under certain circumstances they may also have a destabilizing effect [76,80,81]. Hydrologically, an important factor co-defining the likelihood of bank erosion is soil water content, as positive pore pressure can make the bank material more susceptible to failure [76,82]. For example, vegetation can reduce the overall soil moisture through water losses related to interception and evapotranspiration [83]. These water losses tend to have a positive effect on bank stability, albeit that may vary seasonally [84]. On the other hand, vegetation can enhance local infiltration rate and, to some extent, increase pore pressure, as water delivered by precipitation is concentrated by stemflow and routed by preferential flow pathways associated with root system [85]. Further complexity is introduced by the fact that the influence of this mechanisms may depend on root morphology.

From the mechanical processes standpoint, vegetation adds weight, acting to destabilize the bank [76,86], whereas root system reinforces the bank, increasing its stability [87,88,89]. In addition, roots also promote bank resistance to hydraulic action [84] (Figure 4A). However, the effect of surcharge (added weight) tends to be relatively small. The magnitude of the reinforcement effect depends on the tensile strength of the roots and their distribution [81,90,91]. Importantly, it appears that the mechanical protection is unlikely to be effective in cases in which bank height is much larger than the rooting depth [92,93] (Figure 4B–D). This observation appears to suggest that the stabilizing influence of vegetation should be less prominent (or perhaps even negligible) in large rivers. Yet, empirical evidence reveals that the migration (hence bank retreat) rates are as much as ten-fold lower in vegetated meanders compared to unvegetated ones, even in relatively large channels [94]. Clearly, more research is needed to verify the role of vegetation in such reduced migration rates and to understand in detail the underlying mechanisms. In addition to the above processes, it has also been noted that presence or absence of riparian vegetation can influence subaerial processes that condition banks for erosion [70]. Finally, vegetation can exert control on bank erosion by influencing near-bank hydraulics. For example, research indicates that vegetation succession on point bar can enhance flow steering towards the opposite bank [95]. Similarly, flow characteristics relevant for bank erosion may be influenced by large wood (Figure 4B). Such downed wood, which commonly accumulates at the bank toe, can be derived locally, from trees toppled by the wind and recruited through bank undercutting, or advected from upstream. Recent research suggests that, depending on the density of these logs and their spatial arrangement with respect to the bank and flow structure, such features can both increase and decrease local bank erosion rates [96,97].

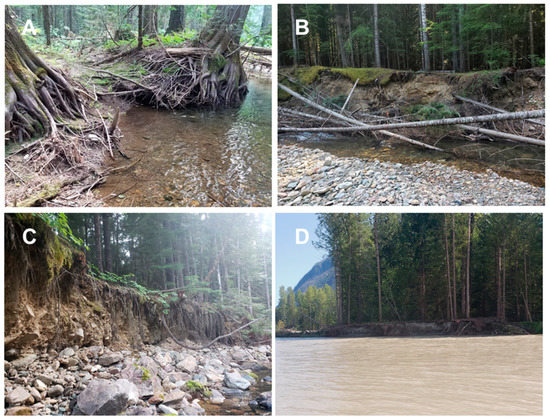

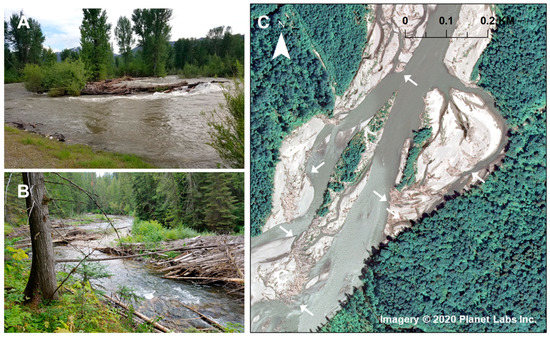

Figure 4.

Vegetation and bank erosion/migration. (A) Bank reinforcement by the root system; (B) Large wood accumulated along the bank; (C) Erosion below rooting zone; (D) Shallow root system has little effect on erosion, especially in larger rivers with high banks (here during a high flow event).

2.1.2. Avulsions

Vegetation also plays an important role for overbank flows and lateral reworking of the valley floor through avulsions [25,98]. These biogeomorphic interactions are less well understood than in the case of bank erosion, partly because the understanding of hydro-geomorphic processes on forested floodplains is generally limited [99], especially so in mountain basins. Most of research on floodplain dynamics has been conducted in low gradient channels but it seems reasonable to assume that this knowledge is largely transferrable, at least to major mountain rivers in principal valleys. Moreover, some relevant work, especially in relation to the role of large wood, has been carried out in the forested rivers of the Pacific Northwest [98,100,101,102]. Taken together, this body of research provides important insight into the biotic controls on the dynamics of multi-thread channels. For example, flow resistance and backwater conditions induced by large wood accumulations (hereinafter also referred to as logjams) promote out-of-bank flows which, ultimately, can result in floodplain erosion and, potentially, avulsions [98,103,104] (Figure 5). This effect is enhanced under the conditions of rapid bed aggradation [105], which may be also induced by in-stream wood, especially channel-spanning jams [106,107,108]. Similarly, it has been shown that the deflection of flow by logjams can regulate the reactivation and reworking of floodplain channels [109] (Figure 5). Generally speaking, vegetation increases floodplain roughness, which in turn results in reduced overbank flow velocities and increased inundation depth and extent; the reduced velocities also translate into diminished boundary forces [110,111,112]. During large floods, the anchoring effect of vegetation (biostabilization) may regulate erosion and deposition that occurs on floodplain surfaces, although extreme events that exceed certain threshold force can also remove the plants [113,114,115,116].

Figure 5.

Large wood promotes avulsions and the development of multi-thread channel morphology. Note the logjams regulating inflow into the secondary and abandoned channels. Sediment storage facilitated by large wood appears to contribute to channel infilling. Flow from top to bottom. Image source: USDA The National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP).

This simple model of the interplay between vegetation (including downed wood), flow and sediment fluxes, can be further extended to consider more nuanced effects that plants may have on lateral geomorphic connectivity. For example, floodplain hydraulic patterns are highly complex, with a mix of channelized and diffusive flow [117,118,119,120]. Experimental research has shown that vegetation plays an important role in focusing shallow flows into well-defined channels [121,122,123]. Similarly, modeling results indicate that dense vegetation stands also deflect the floodplain flow, influencing overbank flow patterns [112,116]. In addition to living vegetation, downed wood on the floodplain has been found to route the flow across the floodplain surface, thereby contributing to the formation of microchannels [124,125,126,127]. Because of the relatively shallow nature of floodplain flows, and because of strongly 3-dimensional flow patterns with areas of high shear, both vegetation and downed wood can exert considerable influence on hydraulic forces thus affecting the magnitude and spatial pattern of erosion and deposition [99]. As a result, it appears that vegetation may be an important factor contributing to the development and organization of floodplain topography [128]. A number of characteristics of the vegetation cover—including individual plant canopy structure or stand-scale biomass—seem to be relevant for such geomorphic effects [116,129]. Thus, vegetation acts in concert and interacts with topography to create the complex hydraulic patterns observed in floodplain flows, with large variation in water surface elevation and flow direction changing substantially with stage [130]. There are further ways in which the biogeomorphic interactions may have important effect on channel avulsions. For instance, it has been shown that presence of riparian vegetation leads to increased sedimentation closer to the bank; this pattern ultimately results in higher and steeper levees [131,132]. The alluvial ridge height in turn influences the likelihood of avulsions [123,133] as well as path selection through the floodplain during an avulsion event [134].

2.1.3. Hillslope Inputs

Vegetation has equally important effects on hillslope processes; although the focus of this review is on the fluvial system, in mountain streams, the processes operating on the adjacent hillslopes may have important and direct influence on channel behavior and characteristics [135,136,137,138,139]. Typically, in mountain landscapes, the primary phenomena delivering clastic material from slopes to the stream network are episodic mass movements [140,141,142,143]. Mass movements are understood here broadly and include diverse types of landslides, debris flows, and so forth. With the exception of deep-seated landslides, in which failure plane is located well below rooting zone, vegetation can influence slope stability through both hydrological and biomechanical effects [58,144] (Figure 6). The key impacts, including the regulation of soil pore pressure and the apparent cohesion associated with root system, mirror closely those discussed above for bank failures [63,145,146]. Hence, to avoid redundancy, a detailed discussion of these mechanisms is not given here; instead, reader is referred to the above-cited reviews. However, it is worth to mention briefly at this point other, more continuous slope processes, such as soil creep and surface erosion, which can also be regulated by vegetation [61,147]. For example, soil creep can be influenced by biotic processes, such as root growth and decay or tree swaying and uprooting; such bioturbation phenomena tend to increase the rate of material fluxes [148,149,150,151,152]. However, on the other hand, trees can also promote accumulation of the material moving downslope and provide bioprotection to soil surface [61]. Moreover, forest canopy can alter not only slope hydrology but also microclimate, which in turn may define the relative importance of the mechanisms that drive soil creep (e.g. freeze-thaw vs. bioturbation) and slow down its overall rates [153,154]. The degree to which plants may influence the processes described above will depend on a range of their traits, such as root architecture [147]. Taken together, just like in case of the valley floor processes, biogeomorphic interactions on hillslopes involve multiple complex phenomena which, in some cases, may can act in opposite directions.

Figure 6.

A source area of a landslide in forested terrain, Washington state. Note the exposed shallow root system as well as vegetation colonizing the lower portion of the scar.

2.2. Longitudinal Connectivity

Vegetation regulates longitudinal geomorphic connectivity primarily through the effects of large in-stream wood, but in larger channels pioneer plants on bar or island surfaces may also play a role (Figure 7). One of the key mechanisms through which these biotic factors affect downstream sediment fluxes is their effect on channel hydraulics. For example, large wood obstructs the flow and increases flow resistance [155,156,157]; this mechanism tends to be especially effective in smaller channels because of potentially high blockage ratio [158]. While such macroroughness elements have the overall effect of reducing reach-average forces available for sediment transport [159], local flow patterns and turbulence induced by the flow obstruction [160,161,162] can, on the other hand, cause local scour [106,162,163]. Therefore, the net effect of large wood on longitudinal connectivity, as mediated by flow hydraulics, may vary depending on the architecture and orientation of the wood accumulation [164,165,166]. Another mechanism through which large wood controls sediment transfer along the channel network is by physically trapping sediment in bar deposits or depositional wedges formed upstream of large wood [106,107,167,168] (Figure 7C).

Both mechanisms are much more efficient when multiple pieces of large wood form complex logjams [28,159,169]. These accumulations of large wood can develop as a result of two distinct groups of processes—in situ deposition (e.g., by mass movement or bank erosion) and fluvial transport—but similar structures can be formed by beaver [26]. Mass movement processes, such as landslides and debris flows, appear to be the dominant mechanism of logjam formation in smaller headwater channels [170,171,172,173,174,175], where fluvial transport of wood is restricted by the dimensions of the channel [176]. In larger streams and rivers, mass movement can still introduce large wood but redistribution of logs recruited by a range of processes (bank erosion, tree throw, etc.), typically during high flows, may be the primary mechanisms of logjam formation [108,177,178,179]. Thus, there is typically a downstream transition in the formative processes and styles of large wood accumulations [24,26,108]. Finally, as noted above, beavers can build dams that, to some extent, functionally resemble log jams; these features can be found on both small and large rivers, in the latter case often along side channels [180,181,182,183]. Sediment storage behind all types of jams (and dams) can be substantial, in some cases exceeding the annual flux tenfold [168,184,185,186,187], and they have been observed to cause hysteresis in sediment transport downstream [188]. These features may regulate downstream passage of major sediment pulses, since wood is often introduced during major disturbances that also recruit clastic material [141,189,190,191]. Logjams are typically structurally stable, as their members are less mobile than individual pieces [192], although their stability decreases with channel dimensions [24]. In smaller channels they were found to last for decades, as decay will lead to gradual release sediment and, finally, a breakup [107,193]. However, jams can also breach more rapidly in response to large flood events [190,194,195]. Following logjam disintegration, some of the sediment may remain stored in terraces [186] or risers in the floodplain [104].

Figure 7.

Large wood and longitudinal connectivity in forested fluvial systems: (A) wood and riparian vegetation influence flow resistance (flow right to left); (B) logjams develop in association with bars and steer the flow (flow right to left); (C) large wood in a large channel—major accumulations marked with white arrows, often forming “hard points” at bar heads (flow from the bottom to the top). (A–C) Note patches of colonizing vegetation associated with logjams. Image source in (C): Planet Team [196].

As noted above, in larger channels, living vegetation interacts with large wood to regulate downstream connectivity. For example, once large wood accumulates into logjams, which provide a “hard points” for bar formation [108,197], these depositional features trap fine material and propagules of riparian plants [198]. This process in turn facilitates the establishment of vegetation on bars [108,199,200] (Figure 7B,C). The growth of the pioneer plants in such protected zones, along with regrowth from living wood floated downstream, create a positive feedback, further encouraging deposition and wood entrapment [128,201,202]. While complex flow around these features also induces local scour [200], the net effect is typically depositional. Unless interrupted by a major erosional event, this process leads to the development of stable islands [203,204], which, ultimately, may be incorporated into the floodplain [98,102,205]. The residence time of sediment making up these stable islands, which seem to be further maintained by the presence of large wood [93], is typically much longer than that in more transient storage elements, such as unvegetated bar forms. However, it is worth noting that both bars and stable islands also steer the flow towards the banks, which, depending on bank resistance, could potentially contribute to sediment recruitment through bank erosion [128].

2.3. Vegetation and Geomorphic Connectivity: A Summary

The preceding discussion clearly highlights the ubiquitous effects on geomorphic connectivity in mountainous fluvial landscapes. These diverse biotic influences on geomorphic processes can be briefly classified, in a perhaps somewhat reductive manner, across the slope and channel processes: (i) the stabilization of sediment (biostabilization/bioprotection) as well as the opposite effect (bioturbation/biogenic transport); (ii) physical entrapment of mobile sediment, leading to soil and landform development or alteration (bioaccumulation/bioconstruction); (iii) the regulation of soil/sediment moisture regime through physiological processes (e.g., transpiration) and the creation of preferential flow pathways, for example, through root system growth; (iv) surface flow routing, for example, through the formation of physical obstructions that deflect the flow or microtopography development as a result of bioconstruction.

3. Vegetation-Geomorphic Connectivity Linkages: Some Challenges to Understanding Fluvial Behavior in Mountain Landscape Systems

There is a wide agreement among the scientific community regarding an urgent need to better understood geomorphic consequences of the ongoing environmental change [206,207,208,209,210,211,212] and develop process-based restoration approaches [54,55,56,213,214]. Mountain landscapes, including fluvial systems, deserve a particular attention. For example, from the ecological point of view, they often provide a physical template for highly diverse and productive ecosystems [215,216] and may serve as important refugia [217,218]. From the social-environmental systems perspective, they are associated with high exposure to geomorphic hazards [219,220,221,222], an effect exacerbated by the often high degree of social vulnerability among mountain communities [220]. At the same time, mountain landscapes and ecosystems are particularly sensitive to disturbances and environmental pressures [48,206,223], which is also manifested in the intensification of geomorphic hazards [219,220,221,222]. Locally high geomorphic connectivity contributes to this sensitivity, as disturbances readily propagate across the landscape [220,224,225]; on the other hand, local dis-connectivity [226,227] may cause any geomorphic responses to vary dramatically across space. Such spatial heterogeneity is of fundamental importance from both ecological and land management perspective [228,229,230]. The complexity in fluvial landscape system’s behavior arising from these properties is further compounded by the vegetation-connectivity linkages outlined in Section 2. The ability of plants to alter geomorphic thresholds, introduce positive feedback loops, and trigger local autogenic disturbances independent of exogenous forcing can greatly contribute to nonlinear system behavior [23]. As a result, the biophysical linkages are likely to be of fundamental importance for geomorphic responses to environmental change and the effectiveness of restoration actions. At the same time, these complex interactions make the dynamics of the landscape system highly difficult to predict or explain [20,231,232].

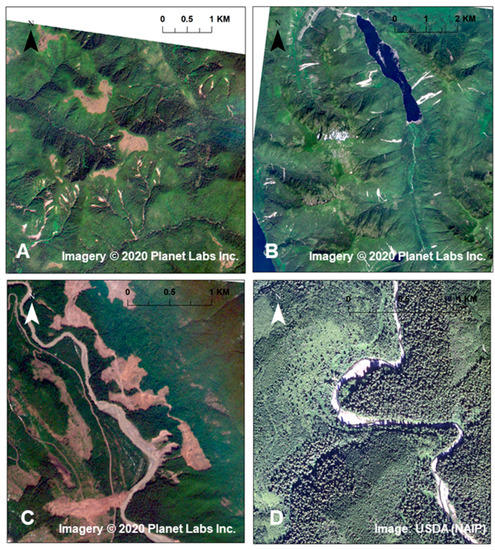

Research to date provides abundant empirical evidence for dramatic responses of geomorphic connectivity in mountain landscapes to vegetation disturbances associated with changing climate and past land management practices. For example, timber harvest, especially clearcutting, has been reported to promote extensive bank erosion [141,233,234] and increase the frequency of slope failures up to an order of magnitude in excess of the background rates [235,236,237,238] (Figure 8A,B). Similarly, greatly increased geomorphic activity, including bank erosion and slope instability, can result from wildfires [239,240,241], the effects of which have been, and are expected to continue to be, exacerbated by the warming climate and shifting precipitation patterns [242]. In addition to local effects, these events can affect areas located downstream. Copious amounts of sediment supplied by such disturbances to channel networks have been observed to result in the formation of sediment pulses, also referred to as sediment waves or slugs [141,174,243,244,245] (Figure 8C,D). In other words, the amplified recruitment of sediment from lateral sources (lateral connectivity) led to increased longitudinal connectivity within the fluvial system. As those pulses propagate downstream, their passage is reflected in cycles of aggradation and degradation, as well as textural evolution of the bed surface [167,244,246]. These effects can persist for decades after the initial disturbance, especially when large quantities of coarse material are supplied [247,248] (Figure 8D). Such changes, in turn, alter disturbance regimes in riverine ecosystems [234,249,250,251,252], which are tightly linked to sediment dynamics [253,254,255]. Therefore, a better understanding of these cascading effects is critical also from the point of view of ecosystem conservation and restoration [256,257]. The aggradation and degradation associated with the passage of sediment pulses have also clear management implications in terms of flood protection and erosion control.

Figure 8.

Forest cover disturbance and geomorphic response. (A,B): a large number of landslide scars (open slope failures and debris flows) in logged terrain. (C) stream-side slope failures generate a sediment pulse—note channel aggradation downstream of the sediment entry points. Flow from the bottom to the top. (D) long-term channel recovery from a sediment pulse—note extensive bars indicating abundant sediment storage well over two decades after a large, episodic supply. Flow from the bottom to the top. Image source in (A–C): Planet Team [196].

However, while past research provides some important insights into the roles that vegetation-connectivity linkages may play in regulating geomorphic responses to environmental change, further work is warranted. For instance, in contrast to the well-researched effects of land use [258,259,260], geomorphic responses to more nuanced and gradual changes in vegetation characteristics, such as those induced by climate variability [261], are much more challenging to identify. In other words, using terminology borrowed from the field of disturbance ecology, the recent focus in biogeomorphology appears to have been primarily on pulse (short-lived) and less on press or ramp (persistent) disturbances [262,263]. To the best of the author’s knowledge, few mountain fluvial systems have been studied holistically, at a broad spatial scale and over long time scales, with an explicit accounting for hillslope and riparian vegetation dynamics and response to both changing land use and climate. In rare cases, such a comprehensive understanding has been achieved for a part of the landscape system, for example channel-floodplain sub-system [264,265,266,267,268,269]. Even outside of mountainous areas, a recent review on European river systems noted that less than 50% of studies of multidecadal channel change accounted for land cover changes [270]. This seems to be an important area in need for more research. For example, recent findings suggest that vegetation and soil changes can either enhance or moderate hydro-climatological effects of changing climate [271]. However, analogous research with respect to geomorphology of fluvial mountain systems appears to be lacking. Taken together, the preceding discussion strongly implies that, to advance our understanding of biogeomorphic interactions and gain insight into their implications for environmental change and watershed restoration, a nested research framework is needed. In such a framework, multiple spatial scales and/or levels of system organization are considered. Investigations at a lower level of hierarchy provide mechanistic explanations of individual phenomena, while the analysis at a higher level of hierarchy accounts for the cumulative system’s response, including emergent phenomena, and provides information about the constraints for key processes of interest [272,273]. Below, I discuss both components of the suggested framework in more detail and provide examples of specific knowledge gaps they could address.

As is clear from the foregoing discussion, an improved mechanistic understanding of the biophysical feedbacks between vegetation and geomorphic connectivity is needed to better understand the behavior of mountain fluvial system that underpins its responses to environmental change or land management and stewardship (e.g., restoration). For example, such mechanistic knowledge is needed to disentangle multiple controls and attribute causality in past dynamics [270] and would certainly facilitate projections into the future. Yet, despite substantial advances in the field of biogeomorphology during the last two decades [38,42,58,59,60,63,274], important knowledge gaps regarding the relevant biophysical interactions remain [39,45,62,275]. For instance, the magnitude and relative importance of often competing biotic effects, as well as their variability (e.g., related to plant age or species), are still relatively poorly explored [76,276,277,278]. Equally importantly, the dynamic co-adjustments between vegetation, flow, and sediment cannot be well understood and quantified without a better insight into the physiological tolerance and responses of plants to hydraulic and geomorphic stress and disturbances [279]; these questions have mostly been explored in detail in a few common, well-studied species [115,280,281]. Along the same vein, it is important to consider phenotypic plasticity of various species to gauge the extent to which short-time plastic responses may modulate plant performance under both climatic and geomorphic stresses [282,283]. Finally, at the scale of plant aggregations that occupy given landforms, a more nuanced view of the role that ecological processes play in the biogeomorphic interactions is also needed. For example, recent research revealed that competition (e.g., self-thinning) and facilitation (e.g., entrapment of organic matter, contributions to mycorrhizal networks and root grafting) may have important geomorphic implications [275].

Crucially, the ability and effectiveness of plants in terms of influencing earth surface processes, as well as their tolerance to physical stress, are closely related to their functional traits, including physiological (e.g., photosynthetic and transpiration rates), biomechanical (e.g., tensile strength), morphological (e.g., root architecture and tensile strength) or life history traits. As a result, a promising approach to advance our understanding of the above issues is to focus on such functional traits, rather than taxonomic classification [45,129]. As a part of such an effort, an interdisciplinary research that integrates plant ecophysiology and biomechanics into biogeomorphology is of crucial importance. Although research into this subject seems to predominantly focus on aquatic macrophytes [284,285], ecological literature may offer a rich source of information for riparian plants as well [286,287]. An extension of trait-based approach to a higher level of biological organization and spatial scale is the framework of guilds/functional groups [288,289,290]. Such guilds can, for example, help identify species that respond in a similar way to a certain geomorphic factor. Future research into this subject should strive to consider explicitly the inherently close links between riparian vegetation and large wood. Although large wood is, arguably, among the best-understood biotic controls on geomorphic connectivity, some areas certainly require further study; examples include the mechanics of wood transport [26,179,200,291] or links between forest ecology and wood recruitment [292,293].

Arguably, an even greater challenge lies in the understanding of how biogeomorphic interactions mediate the effects of environmental change at the basin scale. Because of potentially nonlinear dynamics of these complex fluvial systems, no unique relationship may exist between the disturbances and system responses [20,232,294] and mechanistic approaches, such as those based on the concept of equilibrium, may have limited explanatory and predictive power [232,294,295,296]. In some cases, empirical data lend support to such expectations; for example, complex geomorphic adjustment following a disturbance in a mountain fluvial system, with multiple trajectories, has been demonstrated by Major et al. [297]. Similarly, multiple trajectories can occur in successional responses of vegetation to geomorphic disturbances [298,299]. Given the possibility of nonlinear system behavior, reach-scale biogeomorphic knowledge cannot be readily scaled up without accounting for emergent dynamics that can arise at a broader spatial scale due to, for example, hillslope-channel connectivity or storage within the sediment routing system [206,300]. As noted above, these geomorphic sources of complexity in the overall, basin-scale behavior of the mountain fluvial systems can be further complicated by biogeomorphic interactions. Yet, to the best knowledge of the author, empirical, basin-scale research on geomorphic connectivity in mountain environments, carried out at an adequately long time-scale, has generally been rare. Instead, as noted in Section 1, much of our understanding of medium-to-large basins’ response to climate and land use change are derived from sediment yield studies [301,302,303,304]. In such cases, even the attribution of causality in past system behavior may prove challenging, given that disproportionate response can arise entirely due to internal system dynamics rather than external forcing [305].

A better insight into the role of various feedback loops, which can lead to emergent phenomena and disproportionate responses, remains to be a crucial research need in the context of understanding mountain fluvial system behavior. Consider, for example, sediment pulses associated with hillslope material delivery following a vegetation cover disturbance, such as timber harvest or wildfire. Experimental and modeling work has sought to understand the fundamental physical mechanisms and has greatly advanced our understanding of fluvial responses to these episodic inputs [306,307,308,309,310]. Based on this body of work, an attenuation of the pulse is expected as it moves downstream because sediment dispersion typically dominates over translation [306,308,311,312,313]. Field observations, however, add important nuance to this conceptual model and, more broadly, illustrate that comprehensive source-to-sink research is needed to understand basin-scale geomorphic response. For example, on the one hand, such findings suggest that the propensity for downstream attenuation may be further promoted by lateral connectivity that is associated with overbank sediment storage in unconfined valley sections [314]. On the other hand, several mechanisms could also act to locally augment the pulse. For instance, increased sediment supply has been linked with more rapid bend migration [315] and more frequent avulsions [67,316]. Increased lateral activity was observed on the Chehalis river in response to a major sediment pulse associated with multiple landslides [317], while another empirical study found that in-channel storage and avulsions can regulate downstream evolution of sediment pulses [318]. Depending on the spatial configuration of the channel on the valley floor (structural connectivity), the increased lateral channel activity could in turn induce basal erosion at the slope toe, thus triggering failures and enhancing higher hillslope-channel connectivity [136,319,320,321,322,323] (see Figure 9). Such mass movement activity would also induce vegetation disturbance on the hillslopes and introduce large wood into the fluvial system. The supply of sediment and wood during such an event adds further complexity in terms of downstream connectivity (for large wood, these effects have been described in Section 2.2 [188,194,324]). While the frequency and relative importance of such effects at the basin scale is unclear, in theory, they could result in a self-reinforcing (positive) feedback between hillslope and channel activity, akin to that observed in association with lateral activity on a braidplain and bank undercutting [123,325]. Recent observation of a non-attenuating basin-scale sediment “wave” [326] suggests that the connectivity between the channel and lateral sources indeed need to be considered in studies of sediment pulses. When the whole channel network is considered, the degree to which sediment pulses in different tributaries are synchronized may also greatly complicate the nature of downstream transfer [327,328] and, thus, observed sediment yield.

Figure 9.

Process interaction in fluvial systems: lateral channel activity (channel-valley floor connectivity) leads to slope toe undercutting, triggering or contributing to slope failures (hillslope-channel connectivity). (A) Large, deep-seated landslide along Stillaguamish River, WA. (B) Smaller slides along White Chuck River, WA. Image credit: USDA (NAIP).

4. Summary and Conclusions

Rivers are complex systems, constantly adjusting to a suite of changing governing conditions, which include climate and the characteristics of the biophysical landscape within which they are embedded. Geomorphic connectivity provides a useful framework to consider how vegetation cover regulates clastic material fluxes and how this biotic control may influence fluvial landscape’s behavior, including response to past and future environmental change, or to restoration efforts. In this manuscript I focused specifically on vegetation-connectivity linkages in mountain fluvial environments. Through a selective review, I highlighted the pervasiveness of the plants’ effects on sediment mobility and fluxes and the resulting geomorphic connections within the channel network and between river channels and the broader landscape. These diverse biotic influences on geomorphic processes include biostabilization/bioprotection, bioturbation/biogenic transport, bioaccumulation/bioconstruction, the regulation of soil/sediment moisture regime and the creation of preferential flow pathways, as well as surface flow routing. I supplemented this discussion by outlining specific areas of research that, in my view, are key to better understand biogeomorphic interactions influence the overall behavior of the riverine landscape. Namely, a multi-scale approach was suggested as a promising way forward. On the one hand, the dynamic feedbacks between local hydrogeomorphic processes and plants need to be explored in more detail. For example, such a biogeomorphic perspective would benefit from a stronger integration of plant physiology, biomechanics and morphology into the geomorphic process studies. On the other hand, at the basin scale, a landscape system approach is needed, in which fluvial biogeomorphic interactions are considered jointly with biogeomorphic interactions on the adjacent hillslopes. Because of complex, nonlinear internal dynamics of fluvial systems, and the resultant emergent phenomena, mechanistic understanding of local processes alone may be insufficient to interpret the record of past behavior or forecast future responses to environmental change at such a scale [232,305]. A refined insight, which may result from the hierarchical framework, is also necessary to guide improved management of natural resources, including environmental conservation and restoration [213].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Planet Labs Inc. (Planet.com) for providing access to and enabling use of Planet Scope and Rapid Eye imagery.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Church, M. Bed Material Transport and the Morphology of Alluvial River Channels. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2006, 34, 325–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, M. Channel stability: Morphodynamics and the morphology of rivers. In Rivers–Physical, Fluvial and Environmental Processes; Rowinski, P., Radecki-Pawlik, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 281–321. [Google Scholar]

- Walling, D.E. The Response of Sediment Yields to Environmental Change. IAHS Publ. 1997, 245, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hinderer, M.; Einsele, G. The World’s Large Lake Basins as Denudation-Accumulation Systems and Implications for Their Lifetimes. J. Paleolimnol. 2001, 26, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, M.G.; Lewin, J.; Woodward, J.C. The Fluvial Record of Climate Change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2012, 370, 2143–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerolmack, D.J.; Paola, C. Shredding of Environmental Signals by Sediment Transport. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romans, B.W.; Castelltort, S.; Covault, J.A.; Fildani, A.; Walsh, J.P. Environmental Signal Propagation in Sedimentary Systems across Timescales. Earth Sci. Rev. 2016, 153, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryirs, K. (Dis)Connectivity in Catchment Sediment Cascades: A Fresh Look at the Sediment Delivery Problem. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2013, 38, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, L.J.; Turnbull, L.; Wainwright, J.; Bogaart, P. Sediment Connectivity: A Framework for Understanding Sediment Transfer at Multiple Scales. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2015, 40, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeppl, R.E.; Keesstra, S.D.; Maroulis, J. A Conceptual Connectivity Framework for Understanding Geomorphic Change in Human-Impacted Fluvial Systems. Geomorphology 2017, 277, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, E.; Brierley, G.; Cadol, D.; Coulthard, T.J.; Covino, T.; Fryirs, K.; Grant, G.E.; Hilton, R.G.; Lane, S.N.; Magilligan, F.J.; et al. Connectivity as an Emergent Property of Geomorphic Systems. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, T.; Cavalli, M.; Cerdan, O.; Foerster, S.; Javaux, M.; Lode, E.; Smetanová, A.; Vericat, D.; Brardinoni, F. Indices of Sediment Connectivity: Opportunities, Challenges and Limitations. Earth Sci. Rev. 2018, 187, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A.J.; Wainwright, J.; Brazier, R.E.; Powell, D.M. Is Sediment Delivery a Fallacy? Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2018, 31, 1325–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sinha, R.; Tandon, S.K. Geomorphic Connectivity and Its Application for Understanding Landscape Complexities: A Focus on the Hydro-Geomorphic Systems of India. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, L.; Hütt, M.-T.; Ioannides, A.A.; Kininmonth, S.; Poeppl, R.; Tockner, K.; Bracken, L.J.; Keesstra, S.; Liu, L.; Masselink, R.; et al. Connectivity and Complex Systems: Learning from a Multi-Disciplinary Perspective. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2018, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumm, S.A. To Interpret the Earth: Ten Ways to Be Wrong; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; ISBN 0-521-64602-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fryirs, K.A. River Sensitivity: A Lost Foundation Concept in Fluvial Geomorphology. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2017, 42, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsden, D.; Thornes, J.B. Landscape Sensitivity and Change. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1979, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsden, D. A Critical Assessment of the Sensitivity Concept in Geomorphology. Catena 2001, 42, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.D. Changes, Perturbations and Responses in Geomorphic Systems. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2009, 33, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.F. Landscape Sensitivity in Time and Space—An Introduction. Catena 2001, 42, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, G.; Fryirs, K.; Jain, V. Landscape Connectivity: The Geographic Basis of Geomorphic Applications. Area 2006, 38, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallins, J.A. Geomorphology and Ecology: Unifying Themes for Complex Systems in Biogeomorphology. Geomorphology 2006, 77, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A.M.; Piegay, H.; Swanson, F.J.; Gregory, S.V. Large Wood and Fluvial Processes. Freshw. Biol. 2002, 47, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, E. Floodplains and Wood. Earth Sci. Rev. 2013, 123, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, E. Bridging the Gaps: An Overview of Wood across Time and Space in Diverse Rivers. Geomorphology 2017, 279, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, E.; Kramer, N.; Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Scott, D.N.; Comiti, F.; Gurnell, A.M.; Piegay, H.; Lininger, K.B.; Jaeger, K.L.; Walters, D.M.; et al. The Natural Wood Regime in Rivers. BioScience 2019, 69, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutfin, N.A.; Wohl, E.; Fegel, T.S.; Lynch, L.M. Logjams and Channel Morphology Influence Sediment Storage, Transformation of Organic Matter and Carbon Storage within Mountain Stream Corridors. Available online: http://www.essoar.org/doi/10.1002/essoar.10503253.1 (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Langbein, W.B.; Schumm, S.A. Yield of Sediment in Relation to Mean Annual Precipitation. EOS Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1958, 39, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, J.T.; Goodlett, J.C. Geomorphology and Forest Ecology of a Mountain Region in the Central Appalachians; United States Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, L.B.; Wolman, M.G.; Miller, J.P. Fluvial Processes in Geomorphology; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1964; p. 522. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, I. Man, Vegetation and the Sediment Yields of Rivers. Nature 1967, 215, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viles, H.A. Biogeomorphology; B. Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1988; ISBN 0-631-15405-1. [Google Scholar]

- Viles, H. Biogeomorphology: Past, Present and Future. Geomorphology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupp, C.R.; Osterkamp, W.R.; Howard, A.D. Biogeomorphology, Terrestrial and Freshwater Systems. In Proceedings of the Binghamton Symposium in Geomorphology, Binghampton, NY, USA, 6–8 October 1995; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, L.A.; Viles, H.A.; Carter, N.E.A. Biogeomorphology Revisited: Looking towards the Future. Geomorphology 2002, 47, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.B.; Knaapen, M.A.F.; Tal, M.; Kirwan, M.L. Biomorphodynamics: Physical-biological Feedbacks That Shape Landscapes. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corenblit, D.; Baas, A.C.W.; Bornette, G.; Darrozes, J.; Delmotte, S.; Francis, R.A.; Gurnell, A.M.; Julien, F.; Naiman, R.J.; Steiger, J. Feedbacks between Geomorphology and Biota Controlling Earth Surface Processes and Landforms: A Review of Foundation Concepts and Current Understandings. Earth Sci. Rev. 2011, 106, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterkamp, W.R.; Hupp, C.R.; Stoffel, M. The Interactions between Vegetation and Erosion: New Directions for Research at the Interface of Ecology and Geomorphology. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2012, 37, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.R.; Lane, S.N. Biogeomorphic Feedbacks and the Ecosystem Engineering of Recently Deglaciated Terrain. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2019, 43, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, J.M.; Gibbins, C.; Wainwright, J.; Larsen, L.; McElroy, B. Preface: Multiscale Feedbacks in Ecogeomorphology. Geomorphology 2011, 126, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corenblit, D.; Tabacchi, E.; Steiger, J.; Gurnell, A.M. Reciprocal Interactions and Adjustments between Fluvial Landforms and Vegetation Dynamics in River Corridors: A Review of Complementary Approaches. Earth Sci. Rev. 2007, 84, 56–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bätz, N.; Verrecchia, E.P.; Lane, S.N. The Role of Soil in Vegetated Gravelly River Braid Plains: More than Just a Passive Response? Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2015, 40, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Piégay, H.; Gurnell, A.M.; Marston, R.A.; Stoffel, M. Recent Advances Quantifying the Large Wood Dynamics in River Basins: New Methods and Remaining Challenges. Rev. Geophys. 2016, 54, 611–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabacchi, E.; González, E.; Corenblit, D.; Garófano-Gómez, V.; Planty-Tabacchi, A.-M.; Steiger, J. Species Composition and Plant Traits: Characterization of the Biogeomorphological Succession within Contrasting River Corridors. River Res. Appl. 2019, 35, 1228–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.F. Landscape Sensitivity to Rapid Environmental Change—A Quaternary Perspective with Examples from Tropical Areas. Catena 2004, 55, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, M.G.; Lewin, J. Alluvial Responses to the Changing Earth System. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2008, 33, 1374–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaymaker, O.; Owens, P.N. (Eds.) Mountain Geomorphology and Global Environmental Change. In Mountain Geomorphology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; pp. 277–300. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.; Slaymaker, O. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Sediment Delivery from Alpine Lake Basins, Cathedral Provincial Park, Southern British Columbia. Geomorphology 2004, 61, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibling, M.R.; Davies, N.S. Palaeozoic Landscapes Shaped by Plant Evolution. Nature Geosci. 2012, 5, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Slaymaker, O.; Spencer, T.; Embleton-Hamann, C. Geomorphology and Global Environmental Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 0-521-87812-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, E.S.; Palmer, M.A.; Allan, J.D.; Alexander, G.; Barnas, K.; Brooks, S.; Carr, J.; Clayton, S.; Dahm, C.; Follstad-Shah, J. Synthesizing US River Restoration Efforts; American Association for the Advancement of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 0036-8075. [Google Scholar]

- Beechie, T.J.; Sear, D.A.; Olden, J.D.; Pess, G.R.; Buffington, J.M.; Moir, H.; Roni, P.; Pollock, M.M. Process-Based Principles for Restoring River Ecosystems. BioScience 2010, 60, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.A.; Hondula, K.L.; Koch, B.J. Ecological Restoration of Streams and Rivers: Shifting Strategies and Shifting Goals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2014, 45, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, E.; Lane, S.N.; Wilcox, A.C. The Science and Practice of River Restoration. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 5974–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.F.; Thorne, C.R.; Castro, J.M.; Kondolf, G.M.; Mazzacano, C.S.; Rood, S.B.; Westbrook, C. Biomic River Restoration: A New Focus for River Management. River Res. Appl. 2020, 36, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, R.A. Geomorphology and Vegetation on Hillslopes: Interactions, Dependencies and Feedback Loops. Geomorphology 2010, 116, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterkamp, W.R.; Hupp, C.R. Fluvial Processes and Vegetation—Glimpses of the Past, the Present and Perhaps the Future. Geomorphology 2010, 116, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A.M.; Bertoldi, W.; Corenblit, D. Changing River Channels: The Roles of Hydrological Processes Plants and Pioneer Fluvial Landforms in Humid Temperate, Mixed Load, Gravel Bed Rivers. Earth Sci. Rev. 2012, 111, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, Ł. The Role of Trees in the Geomorphic System of Forested Hillslopes—A Review. Earth Sci. Rev. 2013, 126, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A. Plants as River System Engineers. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2014, 39, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Bogaard, T.A. Dynamic Earth System and Ecological Controls of Rainfall-Initiated Landslides. Earth Sci. Rev. 2016, 159, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, S.; Rodríguez-González, P.M.; Laslier, M. Tracing the Scientific Trajectory of Riparian Vegetation Studies: Main Topics, Approaches and Needs in a Globally Changing World. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 1168–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, J.C.; Bendix, J. Multiple Stressors in Riparian Ecosystems. In Multiple Stressors in River Ecosystems; Sabater, S., Elosegi, A., Ludwig, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 81–110. ISBN 978-0-12-811713-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fryirs, K.A.; Brierley, G.J.; Preston, N.J.; Kasai, M. Buffers, Barriers and Blankets: The (Dis)Connectivity of Catchment-Scale Sediment Cascades. Catena 2007, 70, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingerland, R.; Smith, N.D. River Avulsions and Their Deposits. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2004, 32, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, D.M. Process Dominance in Bank Erosion Systems. In Lowland Floodplain Rivers. Geomorphological Perspectives; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler, D.M. The Impact of Scale on the Processes of Channel-Side Sediment Supply: A Conceptual Model. IAHS Publ. Ser. Proc. Rep. Intern. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 1995, 226, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Abernethy, B.; Rutherfurd, I.D. Where along a River’s Length Will Vegetation Most Effectively Stabilise Stream Banks? Geomorphology 1998, 23, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piégay, H.; Darby, S.E.; Mosselman, E.; Surian, N. A Review of Techniques Available for Delimiting the Erodible River Corridor: A Sustainable Approach to Managing Bank Erosion. River Res. Appl. 2005, 21, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florsheim, J.L.; Mount, J.F.; Chin, A. Bank Erosion as a Desirable Attribute of Rivers. AIBS Bull. 2008, 58, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickin, E.J. Vegetation and River Channel Dynamics. Can. Geogr. Le Géographe Canadien 1984, 28, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, R.G. Influence of Bank Vegetation on Alluvial Channel Patterns. Water Resour. Res. 2000, 36, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, E.R.; Kirchner, J.W. Effects of Wet Meadow Riparian Vegetation on Streambank Erosion. 2. Measurements of Vegetated Bank Strength and Consequences for Failure Mechanics. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. J. Br. Geomorphol. Res. Group 2002, 27, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Collison, A.J.C. Quantifying the Mechanical and Hydrologic Effects of Riparian Vegetation on Streambank Stability. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2002, 27, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Wiel, M.J.; Darby, S.E. A New Model to Analyse the Impact of Woody Riparian Vegetation on the Geotechnical Stability of Riverbanks. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. J. Br. Geomorphol. Res. Group 2007, 32, 2185–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, B.C.; Giles, T.R. Assessing the Effect of Vegetation-Related Bank Strength on Channel Morphology and Stability in Gravel-Bed Streams Using Numerical Models. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2018, 34, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, M.; Darby, S.E. 9 Modelling river-bank-erosion processes and mass failure mechanisms: Progress towards fully coupled simulations. In Gravel-Bed Rivers VI: From Process Understanding to River Restoration; Habersack, H., Piégay, H., Rinaldi, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 11, pp. 213–239. [Google Scholar]

- Pollen, N.; Simon, A.; Collison, A. Advances in Assessing the Mechanical and Hydrologic Effects of Riparian Vegetation on Streambank Stability. Riparian Veg. Fluv. Geomorphol. 2004, 8, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hubble, T.C.T.; Docker, B.B.; Rutherfurd, I.D. The Role of Riparian Trees in Maintaining Riverbank Stability: A Review of Australian Experience and Practice. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, M.; Casagli, N. Stability of Streambanks Formed in Partially Saturated Soils and Effects of Negative Pore Water Pressures: The Sieve River (Italy). Geomorphology 1999, 26, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.D.; Wondzell, S.M. Physical Hydrology and the Effects of Forest Harvesting in the Pacific Northwest: A Review 1. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2005, 41, 763–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollen-Bankhead, N.; Simon, A. Hydrologic and Hydraulic Effects of Riparian Root Networks on Streambank Stability: Is Mechanical Root-Reinforcement the Whole Story? Geomorphology 2010, 116, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.S.; Lehmann, J. Double-Funneling of Trees: Stemflow and Root-Induced Preferential Flow. Ecoscience 2006, 13, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, B.; Rutherfurd, I.D. Does the Weight of Riparian Trees Destabilize Riverbanks? Regul. Rivers Res. Manag. Int. J. Devoted River Res. Manag. 2000, 16, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, B.; Rutherfurd, I.D. The Effect of Riparian Tree Roots on the Mass-Stability of Riverbanks. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2000, 25, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollen, N.; Simon, A. Estimating the Mechanical Effects of Riparian Vegetation on Stream Bank Stability Using a Fiber Bundle Model. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollen, N. Temporal and Spatial Variability in Root Reinforcement of Streambanks: Accounting for Soil Shear Strength and Moisture. Catena 2007, 69, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, B.; Rutherfurd, I.D. The Distribution and Strength of Riparian Tree Roots in Relation to Riverbank Reinforcement. Hydrol. Process. 2001, 15, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.H.; Barker, D. Root-Soil Mechanics and Interactions. Riparian Veg. Fluv. Geomorphol. 2004, 8, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherfurd, I.D.; Grove, J.R. The Influence of Trees on Stream Bank Erosion: Evidence from Root-Plate Abutments. Riparian Veg. Fluv. Geomorphol. 2004, 8, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Beechie, T.J.; Liermann, M.; Pollock, M.M.; Baker, S.; Davies, J. Channel Pattern and River-Floodplain Dynamics in Forested Mountain River Systems. Geomorphology 2006, 78, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ielpi, A.; Lapôtre, M.G. A Tenfold Slowdown in River Meander Migration Driven by Plant Life. Nature Geosci. 2020, 13, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywater-Reyes, S.; Diehl, R.M.; Wilcox, A.C. The Influence of a Vegetated Bar on Channel-Bend Flow Dynamics. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2018, 6, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Rutherfurd, I.D. The Effect of Instream Logs on River-Bank Erosion: Field Measurements of Hydraulics and Erosion Rates. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020, 45, 1677–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Rutherfurd, I.D.; Ghisalberti, M. The Effect of Instream Logs on Bank Erosion Potential: A Flume Study with Multiple Logs. J. Ecohydraulics 2020, 5, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.D.; Montgomery, D.R.; Fetherston, K.L.; Abbe, T.B. The Floodplain Large-Wood Cycle Hypothesis: A Mechanism for the Physical and Biotic Structuring of Temperate Forested Alluvial Valleys in the North Pacific Coastal Ecoregion. Geomorphology 2012, 139–140, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reesink, A.J.H.; Darby, S.E.; Sear, D.A.; Leyland, J.; Morgan, P.R.; Richardson, K.; Brasington, J. Mean Flow and Turbulence Structure over Exposed Roots on a Forested Floodplain: Insights from a Controlled Laboratory Experiment. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, B.D.; Montgomery, D.R. Forest Development, Wood Jams and Restoration of Floodplain Rivers in the Puget Lowland, Washington. Restor. Ecol. 2002, 10, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latterell, J.J.; Scott Bechtold, J.; O’keefe, T.C.; Van Pelt, R.; Naiman, R.J. Dynamic Patch Mosaics and Channel Movement in an Unconfined River Valley of the Olympic Mountains. Freshw. Biol. 2006, 51, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiman, R.J.; Bechtold, J.S.; Beechie, T.J.; Latterell, J.J.; Pelt, R.V. A Process-Based View of Floodplain Forest Patterns in Coastal River Valleys of the Pacific Northwest. Ecosystems 2010, 13, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.D.; Montgomery, D.R.; Sheikh, A.J. Reconstructing the Historical Riverine Landscape of the Puget Lowland. In Restoration of Puget Sound Rivers; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2003; pp. 79–128. [Google Scholar]

- Brummer, C.J.; Abbe, T.B.; Sampson, J.R.; Montgomery, D.R. Influence of Vertical Channel Change Associated with Wood Accumulations on Delineating Channel Migration Zones, Washington, USA. Geomorphology 2006, 80, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaske, B.; Smith, D.G.; Berendsen, H.J.A.; de Boer, A.G.; van Nielen-Kiezebrink, M.F.; Locking, T. Hydraulic and Sedimentary Processes Causing Anastomosing Morphology of the Upper Columbia River, British Columbia, Canada. Geomorphology 2009, 111, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbe, T.B.; Montgomery, D.R. Large Woody Debris Jams, Channel Hydraulics and Habitat Formation in Large Rivers. Regul. Rivers Res. Manag. 1996, 12, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.L.; Bird, S.A.; Hassan, M.A. Spatial and temporal evolution of small coastal gravel-bed streams: Influence of forest management on channel morphology and fish habitats. In Gravel-bed Rivers in the Environment; Klingerman, P.C., Beschta, R.L., Komar, P.D., Bradley, J.B., Eds.; Water Resources Publications, LLC: Highlands Ranch, CO, USA, 1998; pp. 365–392. [Google Scholar]

- Abbe, T.B.; Montgomery, D.R. Patterns and Processes of Wood Debris Accumulation in the Queets River Basin, Washington. Geomorphology 2003, 51, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaske, B.; Smith, D.G.; Berendsen, H.J.A. Avulsions, Channel Evolution and Floodplain Sedimentation Rates of the Anastomosing Upper Columbia River, British Columbia, Canada. Sedimentology 2002, 49, 1049–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.; Nisbet, T.R. An Assessment of the Impact of Floodplain Woodland on Flood Flows. Water Environ. J. 2007, 21, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaske, B.; Maas, G.J.; van den Brink, C.; Wolfert, H.P. The Influence of Floodplain Vegetation Succession on Hydraulic Roughness: Is Ecosystem Rehabilitation in Dutch Embanked Floodplains Compatible with Flood Safety Standards? AMBIO 2011, 40, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Aly, T.R.; Pasternack, G.B.; Wyrick, J.R.; Barker, R.; Massa, D.; Johnson, T. Effects of LiDAR-Derived, Spatially Distributed Vegetation Roughness on Two-Dimensional Hydraulics in a Gravel-Cobble River at Flows of 0.2 to 20 Times Bankfull. Geomorphology 2014, 206, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanson, G.C.; Croke, J.C. A Genetic Classification of Floodplains. Geomorphology 1992, 4, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, G.E.; Swanson, F.J. Morphology and Processes of Valley Floors in Mountain Streams, Western Cascades, Oregon. In Natural and Anthropogenic Influences in Fluvial Geomorphology; Costa, J.E., Miller, A.J., Potter, K.W., Wilcock, P.R., Eds.; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 83–101. ISBN 978-1-118-66430-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bywater-Reyes, S.; Wilcox, A.C.; Stella, J.C.; Lightbody, A.F. Flow and Scour Constraints on Uprooting of Pioneer Woody Seedlings. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 9190–9206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywater-Reyes, S.; Wilcox, A.C.; Diehl, R.M. Multiscale Influence of Woody Riparian Vegetation on Fluvial Topography Quantified with Ground-based and Airborne Lidar. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2017, 122, 1218–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsdorf, D.; Rodríguez, E.; Lettenmaier, D. Measuring Surface Water from Space. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudorff, C.M.; Melack, J.M.; Bates, P.D. Flooding Dynamics on the Lower Amazon Floodplain: 1. Hydraulic Controls on Water Elevation, Inundation Extent and River-floodplain Discharge. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czuba, J.A.; David, S.R.; Edmonds, D.A.; Ward, A.S. Dynamics of Surface-Water Connectivity in a Low-Gradient Meandering River Floodplain. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 1849–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, C.R.; Güneralp, İ.; Hales, B.; Güneralp, B. Scale-Free Structure of Surface-Water Connectivity Within a Lowland River-Floodplain Landscape. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL088378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, M.; Paola, C. Effects of Vegetation on Channel Morphodynamics: Results and Insights from Laboratory Experiments. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2010, 35, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, M.; Paola, C. Dynamic Single-Thread Channels Maintained by the Interaction of Flow and Vegetation. Geology 2007, 35, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gran, K.B.; Tal, M.; Wartman, E.D. Co-Evolution of Riparian Vegetation and Channel Dynamics in an Aggrading Braided River System, Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2015, 40, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piegay, H. Interactions between Floodplain Forests and Overbank Flows: Data from Three Piedmont Rivers of Southeastern France. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. Lett. 1997, 6, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, R.; Darby, S.E.; Sear, D.A. The Influence of Vegetation and Organic Debris on Flood-Plain Sediment Dynamics: Case Study of a Low-Order Stream in the New Forest, England. Geomorphology 2003, 51, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sear, D. Integrating Science and Practice for the Sustainable Management of In-Channel Salmonid Habitat. In Salmonid Fisheries: Freshwater Habitat Management; Kemp, P., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 81–118. ISBN 978-1-4443-2333-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Q.W.; Edmonds, D.A.; Yanites, B.J. Integrated UAS and LiDAR Reveals the Importance of Land Cover and Flood Magnitude on the Formation of Incipient Chute Holes and Chute Cutoff Development. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020, 45, 1441–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Ravazzolo, D.; Bertoldi, W. The Role of Vegetation and Large Wood on the Topographic Characteristics of Braided River Systems. Geomorphology 2020, 367, 107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, R.M.; Merritt, D.M.; Wilcox, A.C.; Scott, M.L. Applying Functional Traits to Ecogeomorphic Processes in Riparian Ecosystems. BioScience 2017, 67, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsdorf, D.; Bates, P.; Melack, J.; Wilson, M.; Dunne, T. Spatial and Temporal Complexity of the Amazon Flood Measured from Space. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, M.G.; de Vries, B.; Braat, L.; van Oorschot, M. Living Landscapes: Muddy and Vegetated Floodplain Effects on Fluvial Pattern in an Incised River. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2018, 43, 2948–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierik, H.J.; Stouthamer, E.; Cohen, K.M. Natural Levee Evolution in the Rhine-Meuse Delta, the Netherlands, during the First Millennium CE. Geomorphology 2017, 295, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnqvist, T.E.; Bridge, J.S. Spatial Variation of Overbank Aggradation Rate and Its Influence on Avulsion Frequency. Sedimentology 2002, 49, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, D.A.; Hajek, E.A.; Downton, N.; Bryk, A.B. Avulsion Flow-Path Selection on Rivers in Foreland Basins. Geology 2016, 44, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.J.; Bradley, J.B. A Process-based Classification System for Headwater Streams. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 1993, 18, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.M. Coupling between Hillslopes and Channels in Upland Fluvial Systems: Implications for Landscape Sensitivity, Illustrated from the Howgill Fells, Northwest England. Catena 2001, 42, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, M. Geomorphic Thresholds in Riverine Landscapes. Freshw. Biol. 2002, 47, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korup, O. Geomorphic Imprint of Landslides on Alpine River Systems, Southwest New Zealand. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2005, 30, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.R.H.; Korup, O. Sediment Cascades in Active Landscapes. In Sediment Cascades; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 89–115. ISBN 978-0-470-68287-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lehre, A.K. Sediment Budget of a Small Coast Range Drainage Basin in North-Central California. In Sediment Budgets and Routing in Forested Drainage Basins; Technical Report PNW-141; Forest and Range Experiment Station, US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service General, Pacific Northwest: Portland, OR, USA, 1982; pp. 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, R.G.; Church, M. The Sediment Budget in Severely Disturbed Watersheds, Queen Charlotte Ranges, British Columbia. Can. J. For. Res. 1986, 16, 1092–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaymaker, O. The Sediment Budget of the Lillooet River Basin, British Columbia. Phys. Geogr. 1993, 14, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.; Church, M. Reconnaissance Sediment Budgets for Lynn Valley, British Columbia: Holocene and Contemporary Time Scales. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2003, 40, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, M.; Wilford, D.J. Hydrogeomorphic Processes and Vegetation: Disturbance, Process Histories, Dependencies and Interactions. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2012, 37, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Noguchi, S.; Tsuboyama, Y.; Laursen, K. A Conceptual Model of Preferential Flow Systems in Forested Hillslopes: Evidence of Self-organization. Hydrol. Process. 2001, 15, 1675–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Ziegler, A.D.; Negishi, J.N.; Nik, A.R.; Siew, R.; Turkelboom, F. Erosion Processes in Steep Terrain—Truths, Myths and Uncertainties Related to Forest Management in Southeast Asia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 224, 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, Ł.; Šamonil, P. Soil Creep: The Driving Factors, Evidence and Significance for Biogeomorphic and Pedogenic Domains and Systems—A Critical Literature Review. Earth Sci. Rev. 2018, 178, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehre, A.K. Rates of soil creep on colluvium-mantled hillslopes in north-central California. In Erosion and Sedimentation in the Pacific Rim; Beschta, R.L., Blinn, R., Grant, C., Ice, G., Swanson, F.J., Eds.; IAHS: Wallingford, UK, 1987; pp. 91–100. ISBN 0144-7815. [Google Scholar]