Social Learning: Methods Matter but Facilitation and Supportive Context Are Key—Insights from Water Governance in Sweden

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- 1.

- How is SL in water governance currently understood?

- 2.

- What can be observed from practical water governance in the Swedish case about

- a.

- SL in terms of trust, commitment, reframing and reflexivity, new knowledge, new relationships, and new activities; and

- b.

- Obstacles and enablers to SL in terms of participants, process design (including methods and facilitation), and context?

- 3.

- What kinds of scientific conclusions and practical recommendations can be derived both from the cases themselves and water governance in general and from a wider context?

2. Background

2.1. Swedish Water Management and Associated Participation

2.2. Participation in Water Governance in Sweden

3. Theory

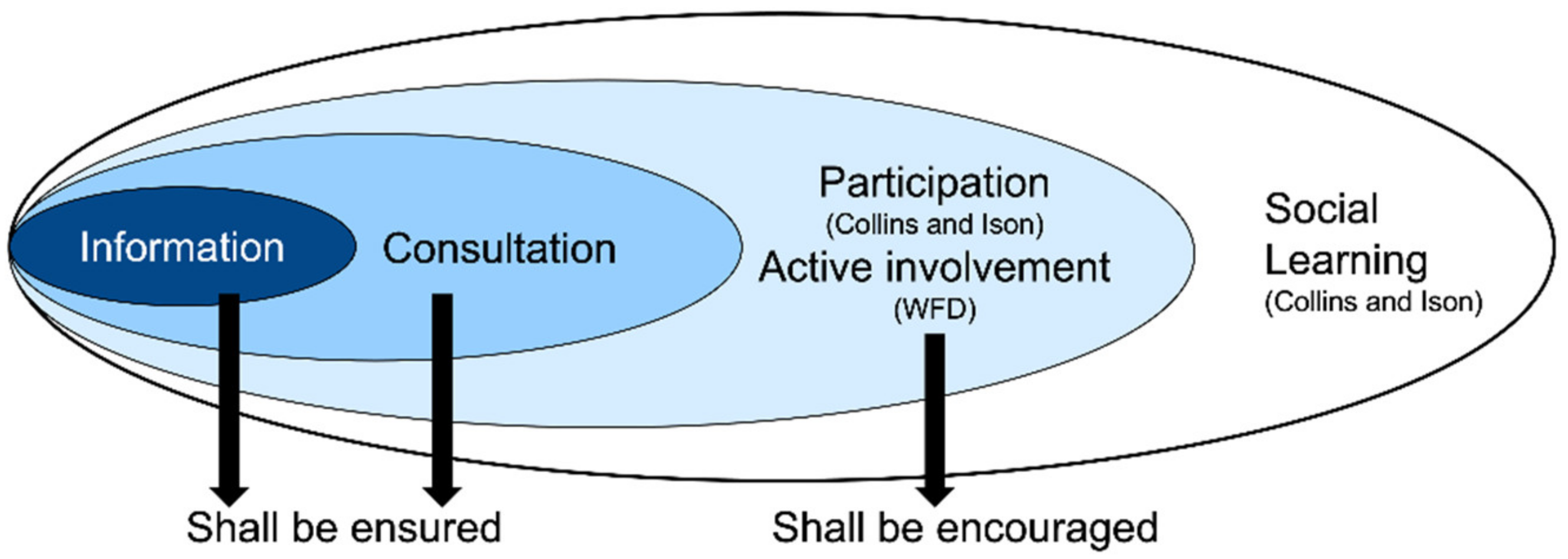

3.1. Participation and Communication

3.2. Social Learning

3.2.1. Orders of Learning

3.2.2. Reflective and Reflexive Communication

3.2.3. Trust, Transparency, and Conflict Management

3.3. Analysing Social Learning: Analytical Framework and Operationalisation of Indicators

4. Approach and Methods

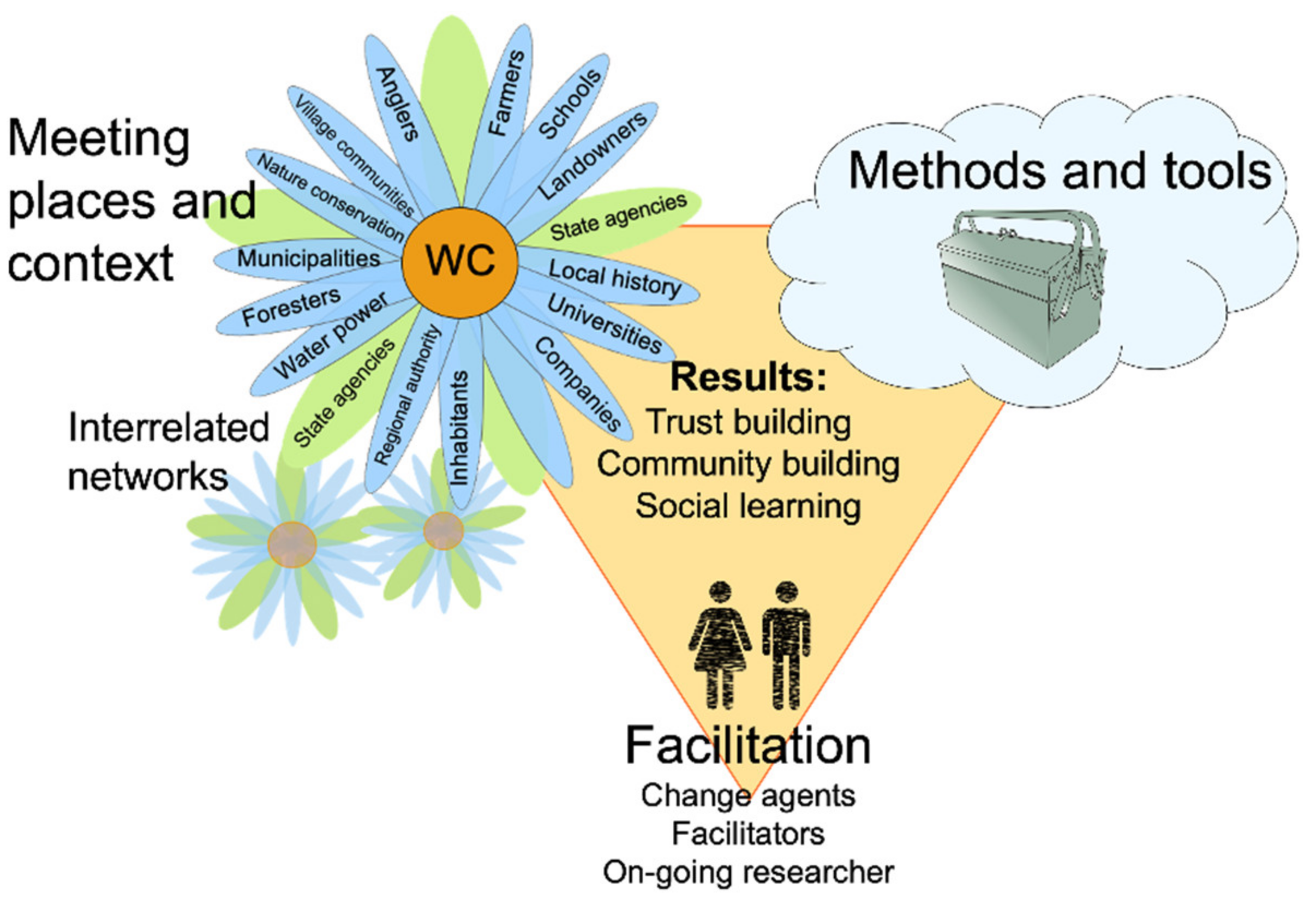

4.1. The Swedish Water Co-Governance Project: Overall Approach, Cases, and Sub-Cases

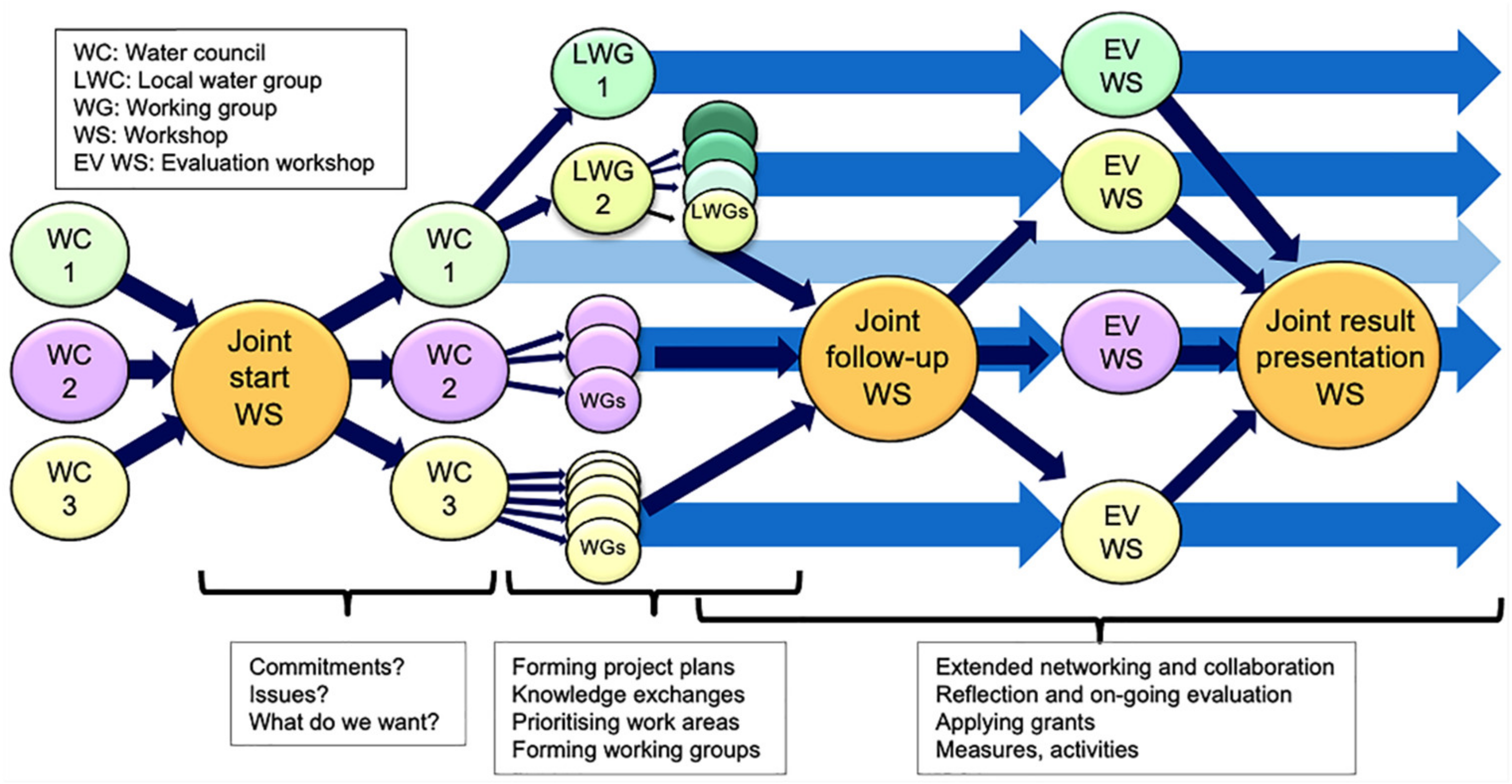

4.2. The Design of the Processes for the Water Councils

4.3. The Overall Research Approach

4.4. Methods of Data Collection

4.4.1. Key Methods and Sources

4.4.2. Complementary Methods and Sources

5. Results: Stepwise and Overall Outcomes

5.1. Relevant Meetings for All the Three WCs and Their Pilots

5.2. The Outcomes of the Steering Group

5.3. Overall Results—Observations and Outcomes of the Four Pilots

5.3.1. Overall Effects of Working Methods Used

5.3.2. Trust—Based on Access, Standing and Influence

5.3.3. Transparency

5.3.4. New Relations

5.3.5. New Knowledge

“It is my opinion that there is a widespread fascination for maps and that they have a function in addition to carrying knowledge and information. Do not know if it is about concretely seeing one’s own place as part of the whole, or about something else. In any case, they function as a tool in themselves to create commitment and often function as icebreakers/conversation openers.” (Municipal official).

5.3.6. New Activities

5.3.7. Commitment

5.3.8. Reflexivity and Reframing

5.3.9. Lock-in Situations

6. Discussion: Observed Patterns and Conceptual Refinement of SL

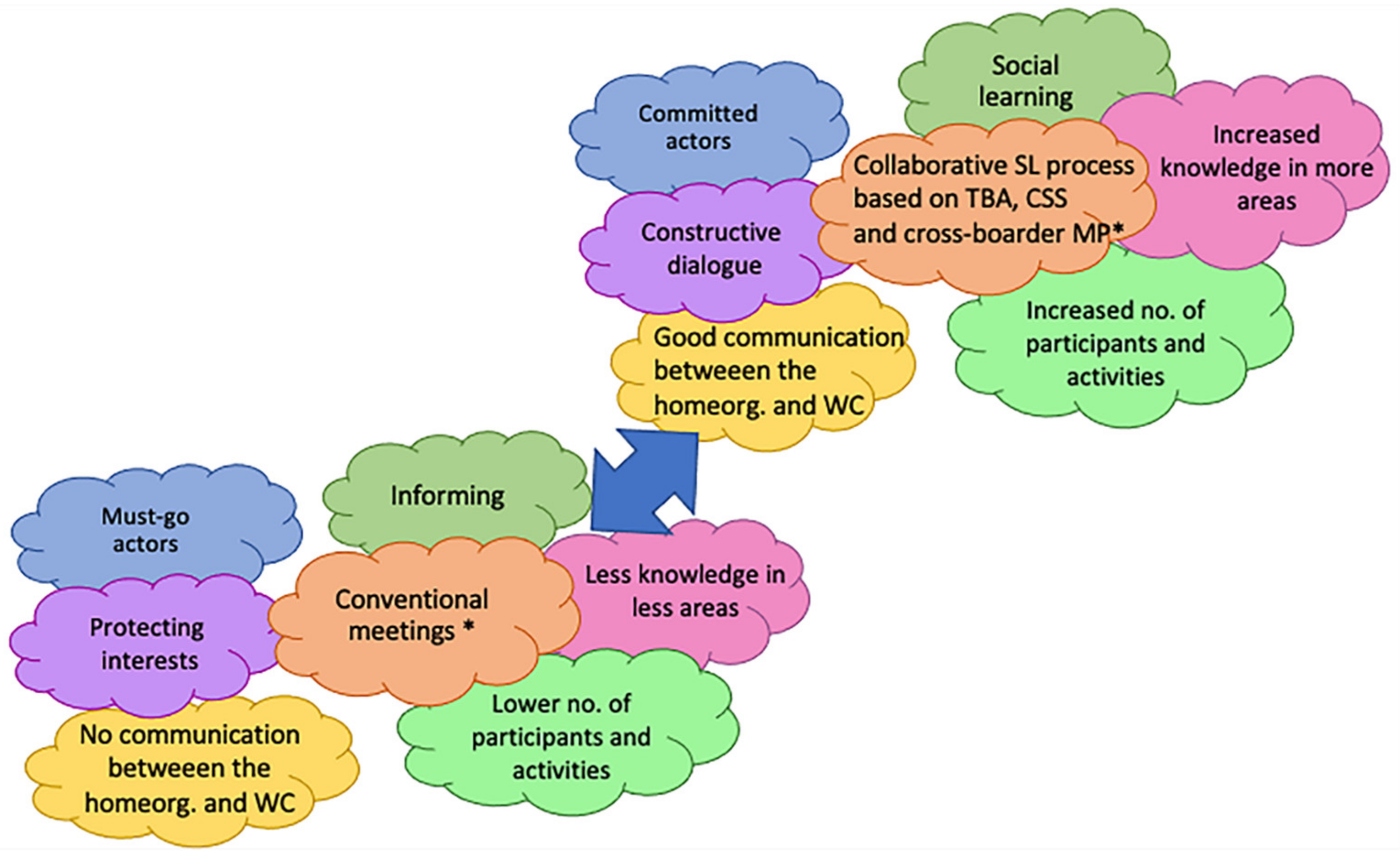

6.1. Gradual Change of Key Process Characteristics through Factors Promoting Social Learning

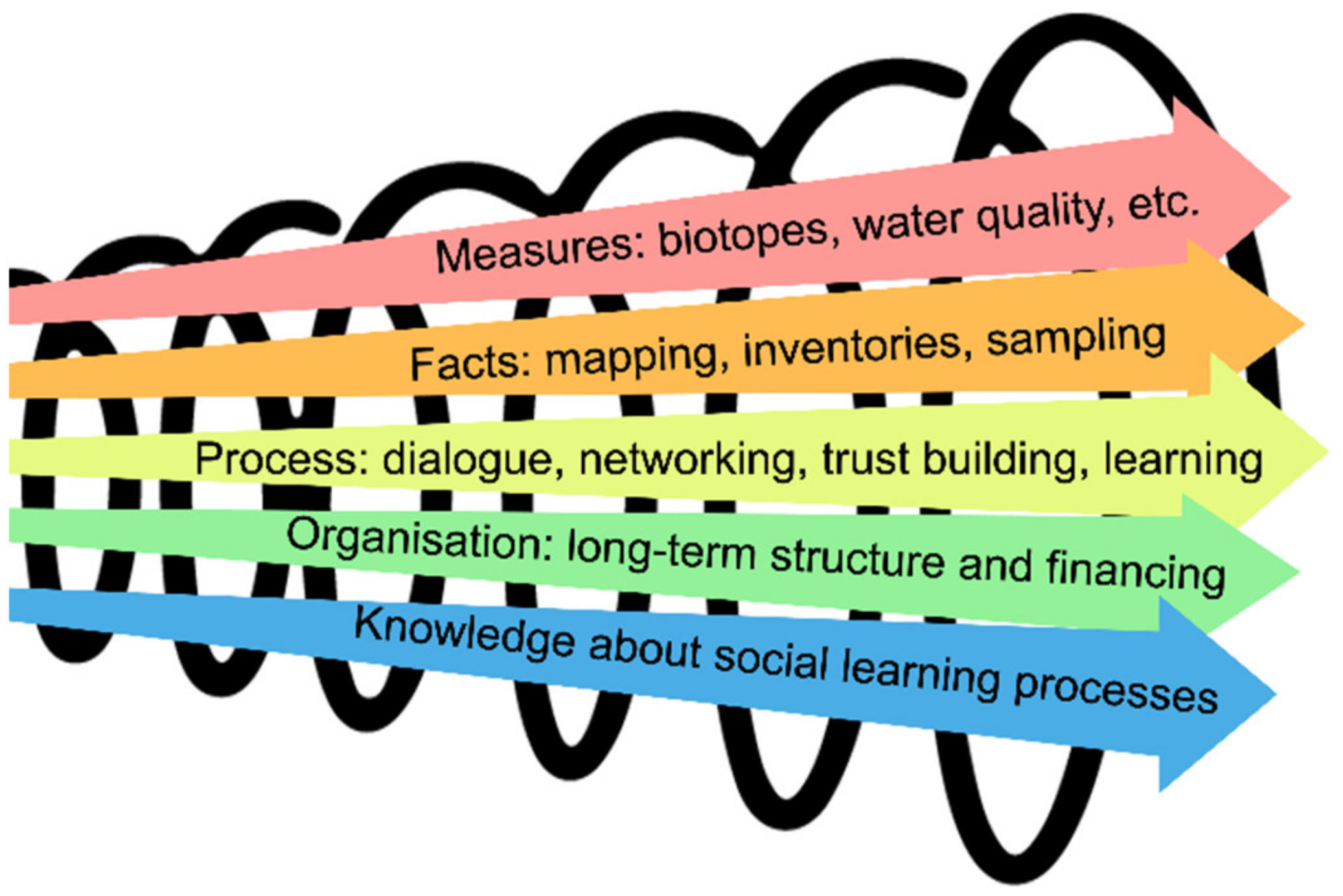

6.2. Diverse Knowledge Production in SL-Processes

6.3. Reflectivity, Reflexivity, and Reframing

6.4. Obstacles to Social Learning (Lock-in Situations) and How to Address Them

6.4.1. Dysfunctional Collaboration Patterns

6.4.2. Power Structures, Trust, and Risks in the Process

6.4.3. Context and Cross-Boundary Work—Both Challenging and Enabling

6.4.4. Mutual Respect and Allowing Difference—A Condition for Resolution

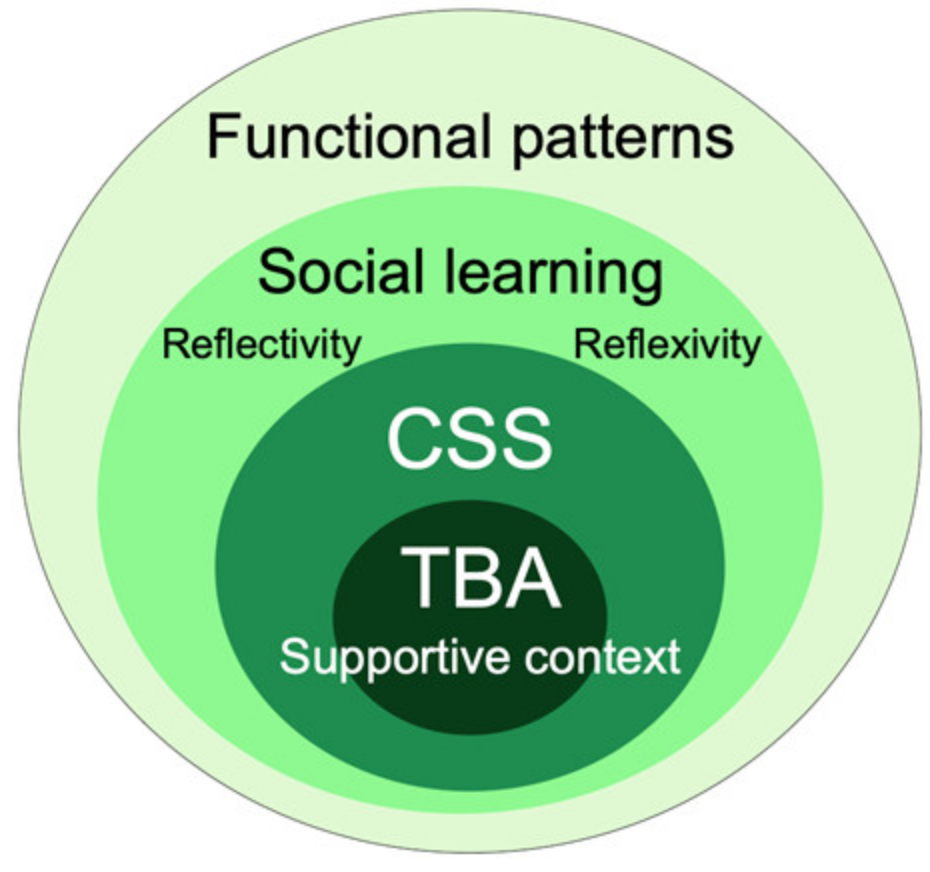

6.5. Synthesis

6.5.1. Participatory Methods Need an Overall Framing by Trust-Based Approaches

6.5.2. Collaboration Supporting Structures Further Promote Social Learning

6.5.3. Functional and Dysfunctional Patterns, Risks, and Reflexivity

6.5.4. Context—Widening Both Process and Perspectives

7. Conclusions and Outlook

7.1. Deepening the Conceptualisation of SL

7.2. Developing SL in Water and Natural Resource Governance

7.3. Outlook: A Wider Context of Application for TBA and CSS

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. EU Water Framework Directive 2000/60; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.; Webber, M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S.; Chuenpagdee, R. Fisheries and coastal governance as a wicked problem. Mar. Policy 2009, 33, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senecah, S.L. The trinity of voice: The role of practical theory in planning and evaluating the effectiveness of environmental participatory processes. In Communication and Public Participation in Environmental Decision Making; Depoe, S.P., Delicath, J.W., Elsenbeer, M.-F.A., Eds.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, K.; Ison, R. Jumping off Arnstein’s ladder: Social learning as a new policy paradigm for climate change adaptation. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, J.; Wal, M.M.v.D.; Beers, P.J.; Wals, A.E.J. Reframing the future: The role of reflexivity in governance networks in sustainability transitions. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 24, 1383–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Broman, K.; Hansen, S. Strategi och Plan för Vattenmyndighetens Kommunikation och Samverkan inom Norra Östersjöns Vattendistrikt; Vattenmyndighetens kansli, Länsstyrelsen i Västmanlands Län: Västmanlands Län, Sweden, 2013; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. European Landscape Convention; European Council: Florence, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Common Implementation Strategy for the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC): Guidance Document no 8: Public Participation in Relation to the Water Framework Directive; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Morf, A. Participation and Planning in the Management of Coastal Resources Conflicts: Case Studies in West Swedish Municipalities; Göteborgs Universitet: Göteborg, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Morf, A.; Kull, M.; Piwowarczyk, J.; Gee, K. Towards a ladder of marine/maritime spatial planning participation. In Maritime Spatial Planning Past, Present, Future; Zaucha, J., Gee, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 219–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J.N. Participatory learning for sustainable agriculture. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uphoff, N.T. Reasons for Success: Learning from Instructive Experiences in Rural Development; Esman, M.J., Krishna, A., Eds.; Kumarian Press (Worldwide) or Vistaar Publications (India and Surroundings): West Hartford, CT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ronnby, A. Den. Lokala Kraften: Människor i Utvecklingsarbete, 1st ed.; Liber Utbildning: Stockholm, Sweden, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wates, N. The Community Planning Handbook: How People Can Shape Their Cities, Towns and Villages in Any Part of the World; Earthscan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A. Common property institutions and sustainable governance of resources. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1649–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Gadgil, M. Traditional ecological knowledge, biodiversity, resilience and sustainability. In Biodiversity Conservation: Problems and Policies; Perrings, C.A., Mäler, K., Folke, C., Jansson, B., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.R.; Sinclair, A.J. Strategies for self-organization: Learning from a village-level community-based conservation initiative in India. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigendal, M.; Östergren, P.-O. Malmös Väg Mot en Hållbar Framtid: Hälsa, Välfärd och Rättvisa, 2nd ed.; Kommissionen för Ett Socialt Hållbart Malmö: Malmö, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Väntänen, A.; Marttunen, M. Public involvement in multi-objective water level regulation development projects—Evaluating the applicability of public involvement methods. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 25, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.; Khotari, U. Participation: The New Tyranny? Zed Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosse, D.; Cooke, B.; Khotari, U. People’s knowledge, participation and patronage: Operations and representations in rural development. In Participation: The New Tyranny? Cooke, B., Khotari, U., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Communication and the Evolution of Society; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.R. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age; University of California Press: Berkley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, C. Wittgenstein, Political Theory and Democracy. In The Democratic Paradox; Verso: London, UK; Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2000; Available online: http://them.polylog.org/2/amc-en.htm (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Abrahamsson, H. Dialog och medskapande i vår tids stora samhällsomdaning. Utbildning och lärande 2015, 9, 20–40. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling, A. “Opening up” and “closing down”. Power, participation, and pluralism in the social appraisal of technology. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2008, 33, 262–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, M.; Gupta, J. The split ladder of participation: A diagnostic, strategic, and evaluation tool to assess when participation is necessary. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 50, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Democracy and Education; Macmillian: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA,, 1991; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Learning and pedagogy in communities of practice. In Learners and Pedagogy; Leach, J., Moon, B., Eds.; Chapman: London, UK, 1999; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E.; McDermott, R.; Snyder, W.M. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology; Jason Aronson Inc.: Northvale, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Transformative learning and sustainability: Sketching the conceptual ground. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 5, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.; Shah, R.; Wedlock, E.; Ison, R.; Blackmore, C. Enhancing Systems Thinking in Practice at the Workplace: eSTEeM final report; The OU Centre for STEM Pedagogy: Milton Keynes, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Temple Smith: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sol, J.; Beers, P.J.; Wals, A.E.J. Social learning in regional innovation networks: Trust, commitment and reframing as emergent properties of interaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 49, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, C. (Ed.) Managing systemic change: Future roles for social learning systems and communities of practice. In Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, the Open University; Springer London Limited: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, W.M.; Wenger, E. Our world as a learning system: A communities-of-practice approach. In Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice; Blackmore, C., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Glasl, F. Konfliktmanagement; Haupt, Freies Geistesleben: Bern/Stuttgart, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2007, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schön, D.A.; Rein, M. Frame Reflection: Towards the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, D.; Clark, W.C.; Alcock, F.; Dickson, N.M.; Eckley, N.; Jäger, J. Salience, Credibility, Legitimacy and Boundaries: Linking Research, Assessment and Decision Making. Work. Pap. Ser. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suchman, M. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Skagerrak and Kattegat Water District Authority. The Four Pilot Projects in Three WCs in Skagerrak and Kattegat Water District, Sweden, Involved in the WaterCoG Project; The Skagerrak and Kattegat Water District Authority: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nolbrant, P. Lokal Samverkan och Medskapande Arbetssätt för Bättre Vatten Resultat och Tankar Från Projektet Water Co-Governance i Sverige; Havs-och Vattenmyndigheten: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2020; Volume 2020:6, p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Prutzer, M. Lokal Samverkan i Vattenförvaltningen Med Vattenråden i Fokus: Utvärdering av Projektet Water Co-Governance i Sverige; Havs-och vattenmyndigheten: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prutzer, M.; Soneryd, L. Samverkan och Deltagande Vattenråd och Vattenförvaltning; Havs och Vattenmyndigheten: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Rural Development: Putting the Last First; Longman Scientific & Technical: Harlow, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, W. Enspirited Envisioning—A Guidebook to the Enspiriting Approach to the Future; FIA International LLC.: Denver, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Illeris, K. Lärande, 2nd ed.; Andersson, S., Ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Heron, J. Cooperative Inquiry: Research into the Human Condition; Sage: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Heron, J.; Reason, P. The Practice of Co-Operative Inquiry: Research “with” rather than “on” People.n.d. Available online: http://www.human-inquiry.com/ciacadem.htm (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Jones, L.; Somekh, B. Observation. In Research Methods in the Social Sciences, 6th ed.; Somekh, B., Lewin, C., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Borowski-Maaser, I.; Graversgaard, M.; Foster, N.; Prutzer, M. Process Evaluation of Selected WaterCoG Pilots—Synthesis; 2020. Available online: https://northsearegion.eu/media/16681/final_watercog_pilotsevaluation_synthesis.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Prutzer, M. Part 2 of WaterCoG Evaluation: Reflection on Pilot Processes in Sweden: Summary of Results; Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prutzer, M. Inledande undersökning inom projektet water co-governance 2017: Sammanställning av de viktigaste enkätfrågorna. In Working Material; Havs-och vattenmyndigheten: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, B.M.; Rasmussen, K.E.; Kemshaw, M.R.; Zornes, D.A. Defining and assessing research quality in a transdisciplinary context. Res. Eval. 2016, 25, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. On human correspondence. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2017, 23, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlmann, M.; Benaim, A.; Muradyan, V. Learning for Change—Introduction to a Process for Collaborative Learning and for Project Assessment; Global Action Plan International and SWEDESD: 2013. Available online: https://legacy17.org/Files/Article-related/L4C.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Sannum, M.; Nolbrant, P. Vision och Handling-Utvärdering och Analys av det Lokala Agenda 21-Arbetet Elva Byar i Svenljunga 1995–1998 Samt Förslag till Arbetsmodell för Lokal Hållbarhet; Studieförbundet Vuxenskolan: Svenljunga, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gilljam, M.; Hermansson, J. (Eds.) Demokratins ideal möter verkligheten. In Demokratins Mekanismer; Liber AB: Malmö, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gilljam, M.; Jodal, O. Fem frågetecken för den deliberativa demokratin. In Demokratins Mekanismer; Gilljam, M., Hermansson, J., Eds.; Liber AB: Malmö, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ernits, H. Omgiven av Gränsgångare: Framväxten av Nya Samverkansroller i Offentlig Sektor; Innovationsplattform Borås: Borås, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Amnå, E. Deltagardemokratin—Önskvärd, nödvändig—Men möjlig. In Demokratins Mekanismer; Gilljam, M., Hermansson, J., Eds.; Liber AB: Malmö, Sweden, 2010; pp. 106–124. [Google Scholar]

- Grimvall, A.; Svedäng, H.; Farnelid, H.; Moksnes, P.-O.; Albertsson, J. Ekosystembaserad Förvaltning Som Metod för att Hantera Negativa Miljötrender och Oklara Orsakssamband; Havsmiljöinstitutet: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Morf, A.; Moodie, J.; Gee, K.; Giacometti, A.; Kull, M.; Piwowarczyk, J.; Schiele, K.; Zaucha, J.; Kellecioglu, I.; Luttmann, A.; et al. Towards sustainability of marine governance: Challenges and enablers for stakeholder integration in transboundary marine spatial planning in the Baltic Sea. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2019, 177, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, A.; Morf, A.; Fjellborg, D. Disputed policy change: The role of events, policy learning, and negotiated agreements. Policy Stud. J. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, J. Sharing the Joy of Nature: Nature Activities for All Ages; ERIC Clearinghouse: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T.; Vergunst, J.L. Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, G.A. Morel Tales: The Culture of Mushrooming; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bonatti, M.; Schlindwein, I.; Lana, M.; Bundala, N.; Sieber, S.; Rybak, C. Innovative educational tools development for food security: Engaging community voices in Tanzania. Futures 2018, 96, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspects | Trust: Senecah (2004) | SL: Ison and Collins (2009) | SL: Sol et al. (2017) | Operationalisation as Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | In terms of: 1. Access 2. Standing 3. Influence | Trust in the process in terms of: Actors act in a way that is agreeable to other actors. | (1a) Time and place for meetings are appropriate. (1b) Information is understandable and accessible. (2a) All participants have a say and can contribute to work. (2b) Listening to each other is respectful. (3a) Internal: Respectfully consider each other’s thoughts. (3b) External: Influence on decisions and respectfully considering input from the WCs. | |

| Transparency | Is also part of the aspect Standing. | Increasing awareness of each other’s expectations. | Personal/group level: (a) openness about own views and roles. (b) Awareness of others’ perspectives.Process level: (a) clear process in terms of decisions, roles, etc. (b) Summarizing activity, processes, and results and distributing them to everyone. (c) Open for diverse perspectives. | |

| New relations | Growing relational capital. | New relationships. | New persons and stakeholders attend with partly new interests. | |

| New knowledge | Development of common knowledge base. | New knowledge. | New knowledge and learning from each other. | |

| New activities | 1. Increasing agreement on purpose and goals, behaviour, and management during the work. 2. Growing under-standing and implementing coordinated activities. | New actions. | Activities as a proxy for agreement, coordinated and implemented, and better understanding of them. Comparing activities done before with new activities through the project (content and quantity). (a) Activities are coordinated and implemented. (b) Better understanding of the activities. | |

| Commitment | In terms of: 1. Motivation, passion; 2. Personal (time); 3. Financial resources. | Expressed enjoyment or dissatisfaction as drivers for acting. 1. Can be expressed explicit and implicit. 2. Time used by the participants in the process. 3. Received grants and fees. | ||

| Reflexivity | Increasing awareness of each other’s expectations. | In terms of “...reorienting and making the meaning of one’s beliefs and experiences explicit…” | Transformed understanding of water issues and about other’s perspectives on a personal level. | |

| Reframing | Increasing agreement on purpose and goals, behaviour, and management during the work. | Reframing in terms of changing perceptions to a common shared understanding. | Transformed understanding of water issues changed, including more and broader perspectives on group level. | |

| Lock-in situations | Lock-in situations. | (a) Low quality of communication (e.g., lack/low level of communication or in terms of content). (b) Signs of conflict escalation and stalemate between actors (e.g., loss of trust, non-collaboration, guarded behaviour). |

| WC 1 (Ätran) | LWG 1 (Vartofta) | LWG 2 (Högvadsån) | WC 2 (Himleån) | WC 3 (Mölndalsån) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catchment area (km2) | 3300 | 35 | 460 | 200 | 280 |

| Dominant land use | Coniferous forest, lakes, and bogs. | Cultivated landscape. | Coniferous forest, lakes, and bogs. | Cultivated landscape. | Urban areas, coniferous forest, lakes, bogs. |

| Main challenges | Eutrophication, ditch cleaning to maintain farming. | Obstacles to migration, cleaned watercourses. | Eutrophication, flooding, exploitations. | Flooding, exploitations, obstacles to migration. | |

| Starting year | 1973 | 2017 | 2017 | 2009 | 2008 |

| No. of members | 23 | Ca. 15 | Ca. 25 | Ca. 12 | 12 |

| No. of municipalities included | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| No. of stakeholders | 11 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Organisation | Association | Informal network | Informal network | Informal network | Formal network |

| Budget (EUR) | 45,000 | 0 | 0 | 4000 | 4000 |

| LWG 1 | LWG 2 | WC 2 | WC 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Wetland constructions. | Biotope rehabilitation. Removing obstacles for fish migration. | ||

| Surveys | Watercourse hikes. | Nature inventories. Electric fishing. | Water sampling. Pedagogic water environments. Cultural history. | Pedagogic water environments. |

| Information | Information paths. | Reports Day of Himleån. School information. | Reports. Politician information. Information signs. Watercourse hikes. | |

| Influence community planning | Meeting with municipality. | Meeting with municipality. | ||

| Letters | Referrals and letters. |

| WC 1 (LWG 1 and 2) | WC 2 | WC 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to the WC process internally | Open participation. Info. difficult to under-stand/lack of relevant info (Approx. 35%). | Open participation. Info. difficult to understand/lack of relevant info (0%). | Rule-based participation. Info. difficult to understand/lack of relevant info (8%). |

| Standing in the WC process internally * | Dialogue-oriented. | Dialogue-oriented. | Too little info. from the participants. Info-oriented- Protecting interests. |

| Average perceived change in dialogue based on individual ratings. ** | 2.73➔4.25 (+1.52) | 3.8➔4.0 (+0.2) | 2.8➔3.15 (+0.35) |

| Influence in WC (internal) *** | Respectful consideration of everyone’s thoughts—Often. | Respectful consideration of everyone’s thoughts—Often. | Respectful consideration of everyone’s thoughts—Less often. |

| Influence on government decisions (external) | Little opportunity to influence decisions (58%). | Little opportunity to influence decisions (17%). | Little opportunity to influence decisions (58%). |

| Perceived increase in knowledge | Five different knowledge areas identified. | Six different knowledge areas identified. | Two different knowledge areas identified. |

| Self-rated commitment. | LWG 1: Decreased commitment (50%), unchanged (50%). LWG 2: Great commitment—increased (91%), unchanged (9%). | Great commitment—but only a little greater than at the beginning of the project (100%). | Commitment unchanged (91%), decreased (9%). |

| Key Methods\Effect on: | Trust (Access, Standing, Influence) | Relations | Knowledge | Activities | Commitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open point of departure (avoiding complete answers from the outset) | Different perspectives invited from the beginning involved in designing of content opened for constructive dialogue. (o) | New participants started up several local water groups based on the participant’s own suggestions. (o) | The design and methods are based on open starting points. It increased exchange of knowledge. (e) | New ideas for activities and measures. (e, o) | Being able to participate and formulate visions, goals, and work has increased commitment. (o) |

| Promoting and emphasising diversity in the group | Increased dynamics in the conversation through more perspectives. (o) | Broader perspectives engage more people. Opportunity for greater collaboration. (o) | Increased diversity of perspectives and knowledge increased learning and holistic understanding. (o) | Increased ideas for improvement, measures, and how they were implemented in collaboration have arisen. (o) | Greater diversity of knowledge and perspectives increased interest and commitment. (o) |

| Emphasis on listening to others—without a need to agree (instead of persuading others of own standpoint) | Does not get caught up in argumentation and conflict, but all participants’ thoughts have time to emerge. (o) | Better opportunity to see collaboration opportunities. (interpreted, based on experience) | Opportunity to listen to everyone’s perspectives, means more learning. (o) | Collaboration around activities and measures can arise more easily. (interpreted, based on experience) | Having time to tell and be listened to and hear other people’s commitment strengthens your own commitment. (o) |

| Thinking for yourself and writing own small notes to share | Greater awareness: everyone’s thoughts are important. (e,o) Curiosity about other’s thoughts. (o) | Increased active participation as more people share their thoughts. (e,o) | Time for reflection where lessons about process are formulated. (e) | New ideas for activities and measures were encouraged. (o) | Emphasises the importance of everyone’s thoughts. Get all thoughts into groups. (e, o) |

| Working in small groups (2–6 persons; as a start-up and complement to large groups) | Easier to get to know each other and everyone had a say. (e,o) | More people actively participate through conversations. (o) | Easier to share knowledge by having time to tell and listen to each other. (o) | Ideas about activities and measures were developed in conversations. (o) | Easier to express commitment and thoughts. (o) |

| Reflection round at the end of a meeting (sharing experiences, thoughts, feelings, ideas) | The reflection increased understanding of each other and influenced the process. (o) | The reflection provided an opportunity to develop and improve the collaboration. (e,o) | Reflecting on what you have done and hearing others’ reflections increased learning. (e,o) | Ideas for improvements of activities/measures can be formulated. (interpreted, based on experience) | Reflecting on what has happened and the process. Influencing the form of the process increased commitment. (o) |

| WC 1 | WC 2 | WC 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 25➔58 | 8➔35 | 15➔16 |

| No. of stakeholders | 10➔14 | 3➔7 | 9➔9 |

| No. of WG/LWG 1 | 3➔10 | 3➔9 | 2➔3 |

| No. of external activities | 2➔16 | 2➔9 | 2➔4 |

| Budget 2017–2019 (SKR) | 1.7➔7.3 M (+330%) | 210➔740 K (+250%) | 210➔370 KR (+76%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prutzer, M.; Morf, A.; Nolbrant, P. Social Learning: Methods Matter but Facilitation and Supportive Context Are Key—Insights from Water Governance in Sweden. Water 2021, 13, 2335. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13172335

Prutzer M, Morf A, Nolbrant P. Social Learning: Methods Matter but Facilitation and Supportive Context Are Key—Insights from Water Governance in Sweden. Water. 2021; 13(17):2335. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13172335

Chicago/Turabian StylePrutzer, Madeleine, Andrea Morf, and Peter Nolbrant. 2021. "Social Learning: Methods Matter but Facilitation and Supportive Context Are Key—Insights from Water Governance in Sweden" Water 13, no. 17: 2335. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13172335

APA StylePrutzer, M., Morf, A., & Nolbrant, P. (2021). Social Learning: Methods Matter but Facilitation and Supportive Context Are Key—Insights from Water Governance in Sweden. Water, 13(17), 2335. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13172335