Not All Rivers Are Created Equal: The Importance of Spring-Fed Rivers under a Changing Climate

Abstract

1. Introduction

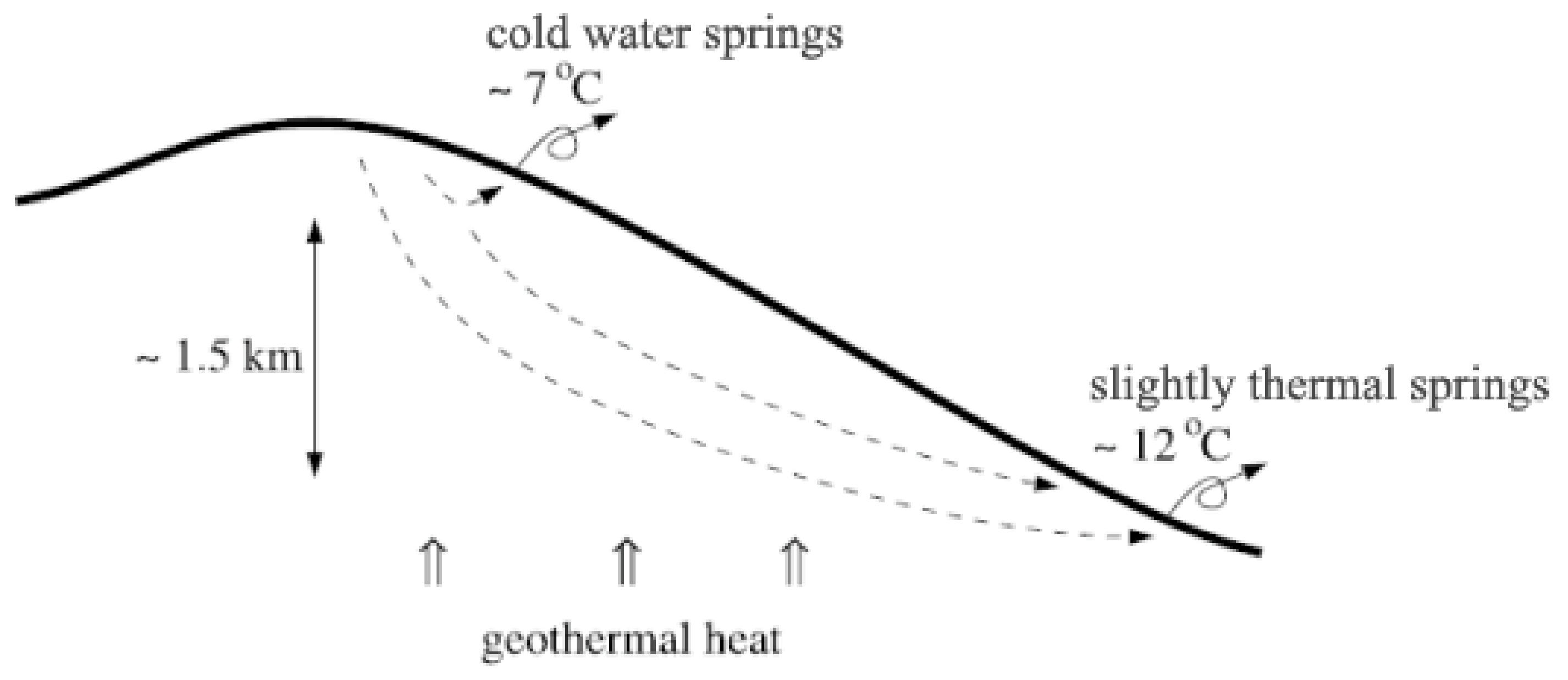

2. Volcanic Spring Geology and Physical Processes

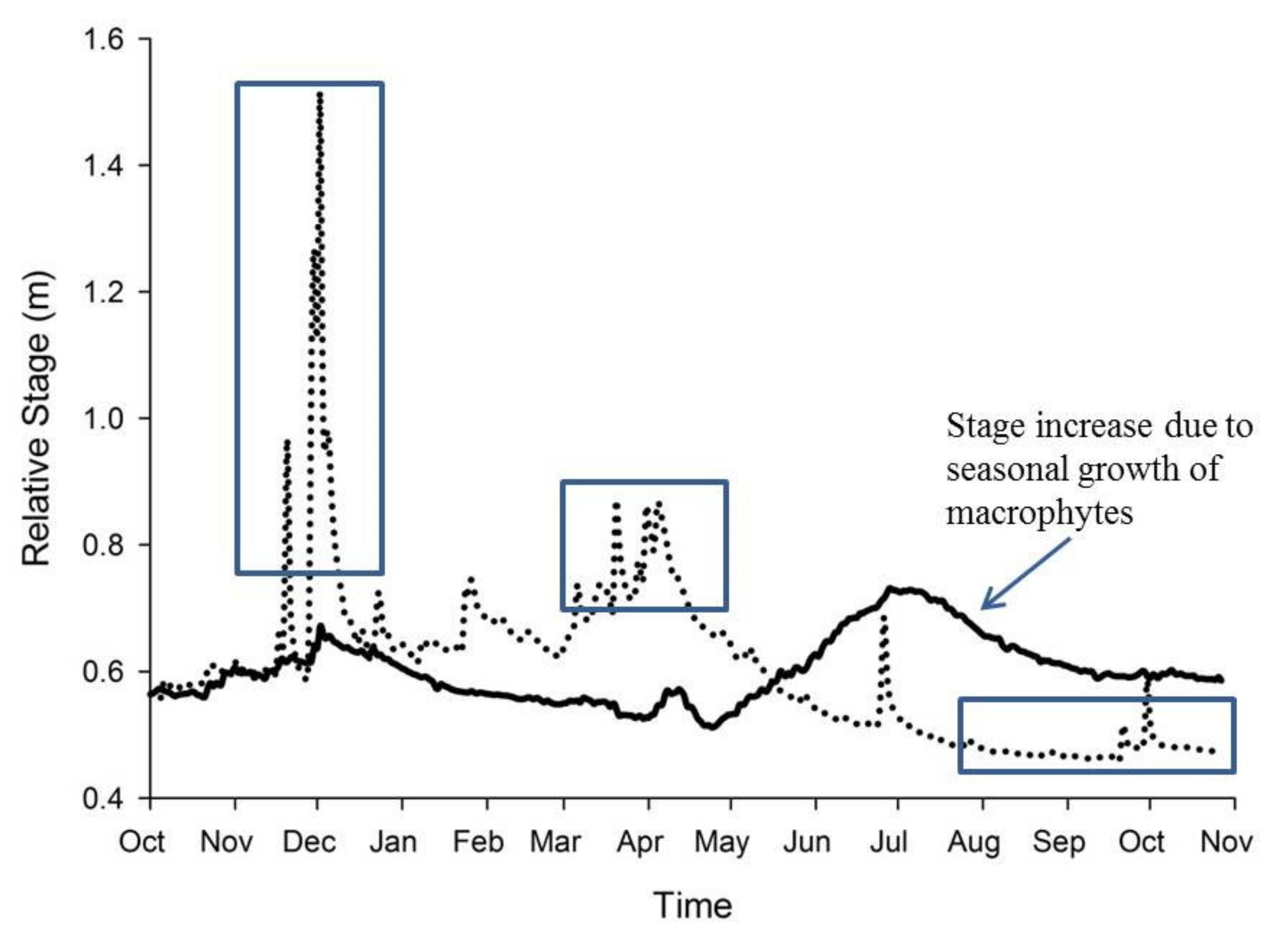

3. Spring-Fed River Geomorphology

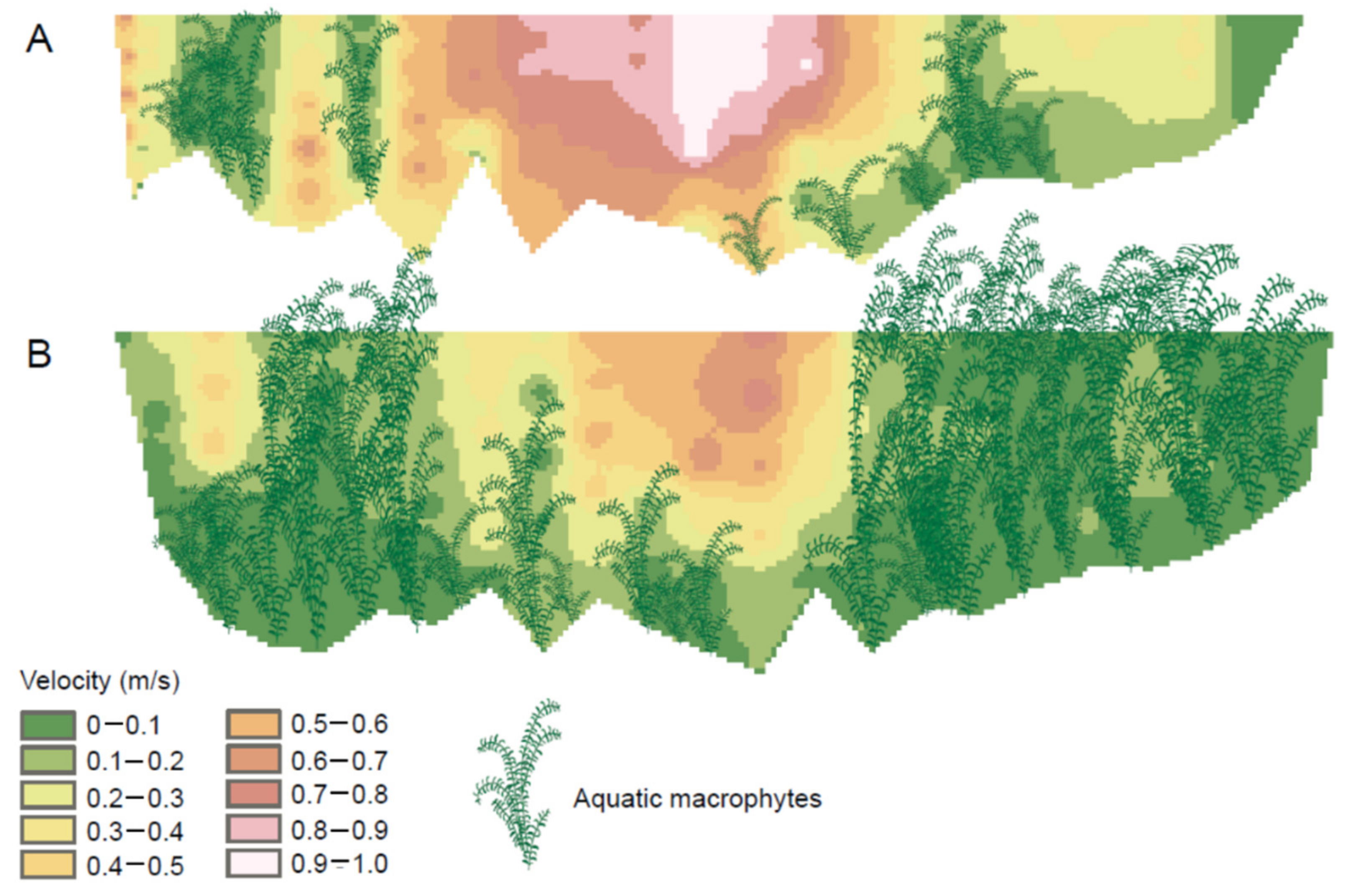

4. Macrophytes and the Stream Environment

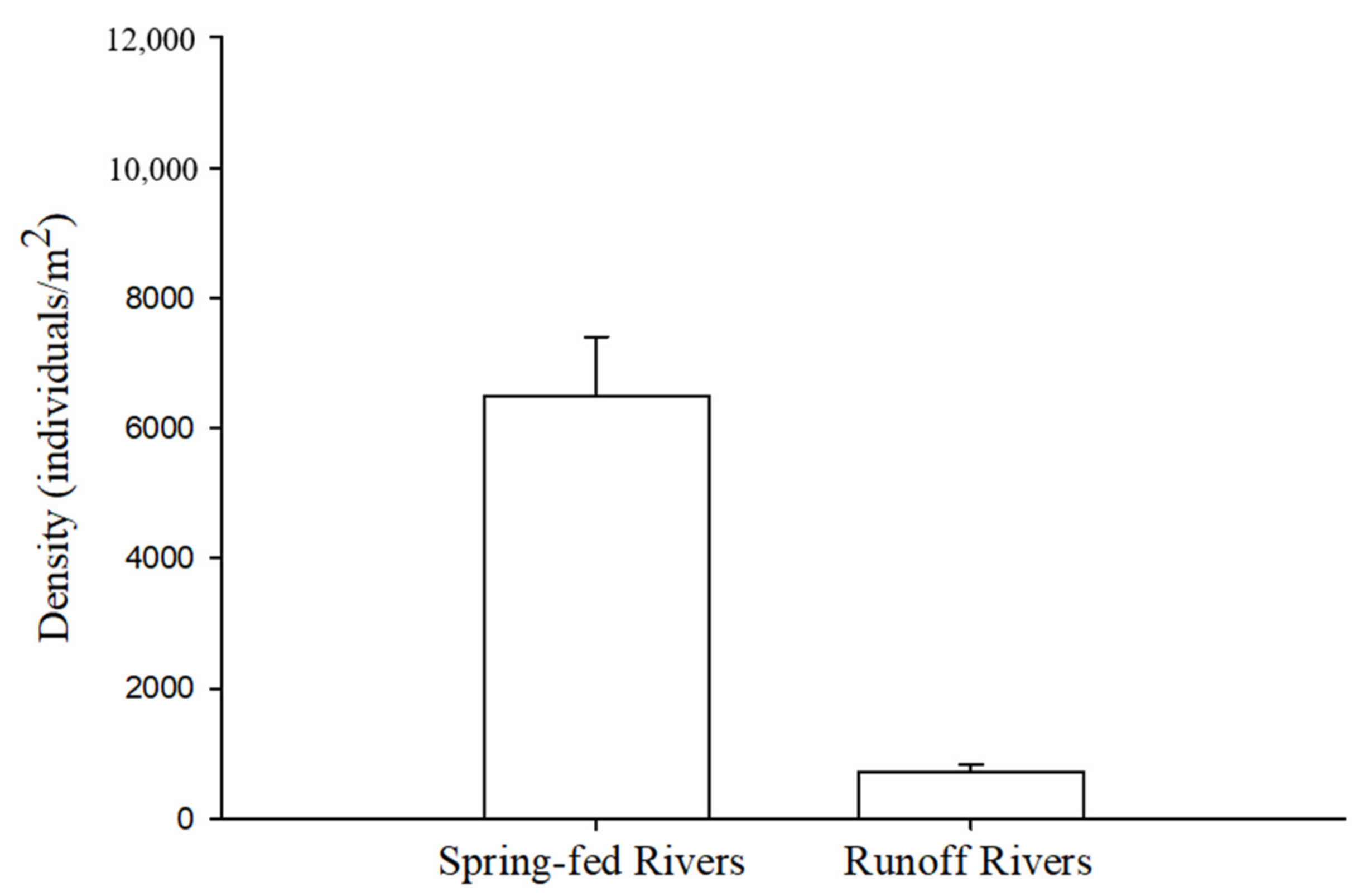

5. Macroinvertebrate Communities

6. Macroinvertebrate Diversity

7. Salmonids and Spring-Fed Rivers

8. Spring-fed Rivers and Climate Change

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ricciardi, A.; Rasmussen, J.B. Extinction Rates of North American Freshwater Fauna. Conserv. Biol. 1999, 13, 1220–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, P.B.; Williams, J.E. Biodiversity Loss in the Temperate Zon-Decline of Native Fish Fauna of California. Conserv. Biol. 1990, 4, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, P.B.; Lusardi, R.A.; Samuel, P.J.; Katz, J.V.E. State of the Salmonids: Status of California’s Emblematic Fishes; 579: UC Davis; Center for Watershed Sciences and California Trout: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, S.J.; Isaak, D.J.; Luce, C.H.; Neville, H.M.; Fausch, K.D.; Dunham, J.B.; Dauwalter, D.C.; Young, M.K.; Elsner, M.M.; Rieman, B.E.; et al. Flow regime, temperature, and biotic interactions drive differential declines of trout species under climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14175–14180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantonati, M.; Füreder, L.; Gerecke, R.; Jüttner, I.; Cox, E.J. Crenic habitats, hotspots for freshwater biodiversity conservation: Toward an understanding of their ecology. Freshw. Sci. 2012, 31, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, L.E.; Meretsky, V.J. (Eds.) Aridland Springs in North America: Ecology and Conservation; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2008; p. 406. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, R.A.; Jeffres, C.A.; Moyle, P.B. Stream macrophytes increase invertebrate production and fish habitat utilization in a California stream. River Res. Appl. 2018, 34, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.M.; Anderson, N.H. The Insect Fauna of Spring Habitats in Semiarid Rangelands in Central Oregon. J. Kans. Entomol. Soc. 1995, 68, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D.; Scarsbrook, M.R.; Harding, J.S. Spatial biodiversity patterns in a large New Zealand braided river. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2006, 40, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.J.; Moog, D.B. The geometric, sedimentologic and hydrologic attributes of spring-dominated channels in volcanic areas. Geomorphology 2001, 39, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrin, M.; Giberson, D.J. Life history and production of mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera) in a spring-fed stream in Prince Edward Island, Canada: Evidence for population asynchrony in spring habitats? Can. J. Zool. 2003, 81, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantonati, M.; Stevens, L.; Segadelli, S.; Springer, A.; Goldscheider, N.; Celico, F.; Filippini, M.; Ogata, K.; Gargini, A. Ecohydrogeology: The interdisciplinary convergence needed to improve the study and stewardship of springs and other groundwater-dependent habitats, biota, and ecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 110, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, J.H. The Decline of the Shasta River King Salmon Run. In Bureau of Fish and Wildlife: California Division of Fish and Game; California Division of Fish and Game: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- NRC. Endangered and Threatened Fishes in the Klamath River Basin; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, R.A.; Bogan, M.T.; Moyle, P.B.; Dahlgren, R.A. Environment shapes invertebrate assemblage structure differences between volcanic spring-fed and runoff rivers in northern California. Freshw. Sci. 2016, 35, 1010–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, R.A.; Hammock, B.G.; Jeffres, C.A.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Kiernan, J.D. Oversummer growth and survival of juvenile coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) across a natural gradient of stream water temperature and prey availability: An in situ enclosure experiment. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2020, 77, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzer, O.E. Large Springs in the United States; US Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett, J.; Poeschel, K.; Thornton, J. A Water-Resources Appraisal of the Mount Shasta Area in Northern California, 1985; Water-Resources Investigations Report 87-4239; US Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- James, E.; Manga, M.; Rose, T.; Hudson, G. The use of temperature and the isotopes of O, H, C, and noble gases to determine the pattern and spatial extent of groundwater flow. J. Hydrol. 2000, 237, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannet, M.W.; Lite, K.E.; Morgan, D.S.; Collins, C.A. Groundwater Hydrology of the Upper Deschute Basin, Oregon; Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4162; United States Geological Survey: Portland, OR, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ingebritsen, S.E.; Sherrod, D.R.; Mariner, R.H. Rates and patterns of groundwater flow in the Cascade Range Volcanic Arc, and the effect on subsurface temperatures. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1992, 97, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, T.P.; Davisson, M.L.; Criss, R.E.; Roses, T.P. Isotope hydrology of voluminous cold springs in fractured rock from an active volcanic region, northeastern California. J. Hydrol. 1996, 179, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tague, C.; Grant, G.E. A geological framework for interpreting the low-flow regimes of Cascade streams, Willamette River Basin, Oregon. Water Resour. Res. 2004, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, A.; Grant, G.E.; Lewis, S.L. A River Runs Underneath It: Geological Control of Spring and Channel Systems and Management Implications, Cascade Range, Oregon. In Advancing the fundamental sciences. Proceedings of the Forest Service National Earth Sciences Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 18–22 October 2004; General Technical Report PNW-GTR (689, Part 2); Furniss, M.J., Clifton, C.F., Ronnenberg, K.L., Eds.; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 2007; pp. 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Nathenson, M.; Thompson, J.; White, L. Slightly thermal springs and non-thermal springs at Mount Shasta, California: Chemistry and recharge elevations. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2003, 121, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingebritsen, S.; Mariner, R. Hydrothermal heat discharge in the Cascade Range, northwestern United States. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2010, 196, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M. Using Springs to Study Groundwater Flow and Active Geologic Processes. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2001, 29, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariner, R.; Evans, W.; Presser, T.; White, L. Excess nitrogen in selected thermal and mineral springs of the Cascade Range in northern California, Oregon, and Washington: Sedimentary or volcanic in origin? J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2003, 121, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M.; Kirchner, J.W. Interpreting the Temperature of Water at Cold Springs and the Importance of Gravitational Potential Energy. Water Resour. Res. 2004, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.D.; Castillo, M.M. Stream Ecology: Structure and Function of Running Waters, 2nd ed.; Springer: Dordrect, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, D.D.; Robinson, C.T. Resource Limitation in a Stream Community: Phosphorus Enrichment Effects on Periphyton and Grazers. Ecology 1990, 71, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavik, K.; Peterson, B.J.; Deegan, L.A.; Bowden, W.B.; Hershey, A.E.; Hobbie, J.E. Long-Term Responses of the Kuparuk River Ecosystem to Phosphorus Fertilization. Ecology 2004, 85, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.F.; Wallace, J.B.; Rosemond, A.D.; Eggert, S.L. Whole-System Nutrient Enrichment Increases Secondary Production in a Detritus-Based Ecosystem. Ecology 2006, 87, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, J.M.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Hansen, B.; Casey, W.H. Contribution of bedrock nitrogen to high nitrate concentrations in stream water. Nature 1998, 395, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, J.M.; Dahlgren, R.A. Nitrogen in rock: Occurrences and biogeochemical implications. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2002, 16, 65-1–65-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, R.; Jeffres, C.; Nichols, A.; Deas, M.; Willis, A.; Mount, J. Geologic Sources of Nutrients for Aquatic Ecosystems; American Geophysical Union: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, P.J.; Stamm, J. The hydrology and form of spring-dominated channels. Geomorphology 1995, 12, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M.; Kirchner, J.W. Stress partitioning in streams by large woody debris. Water Resour. Res. 2000, 36, 2373–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, D.W.; Chapin, D.M.; Devries, P.; Ramey, M.P. Flow Regime and Ecosystem Interactions in Spring-Dominated Streams: Implications for Selecting Instream Flow Methods. Hydroécologie Appliquée 2004, 14, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.E.; Anderson, D.E.; Springer, A.E. The morphology and hydrology of small spring-dominated channels. Geomorphology 2008, 102, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, J.; Wharton, G.; Bass, J.; Heppell, C.; Wotton, R. The effects of seasonal changes to in-stream vegetation cover on patterns of flow and accumulation of sediment. Geomorphology 2006, 77, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

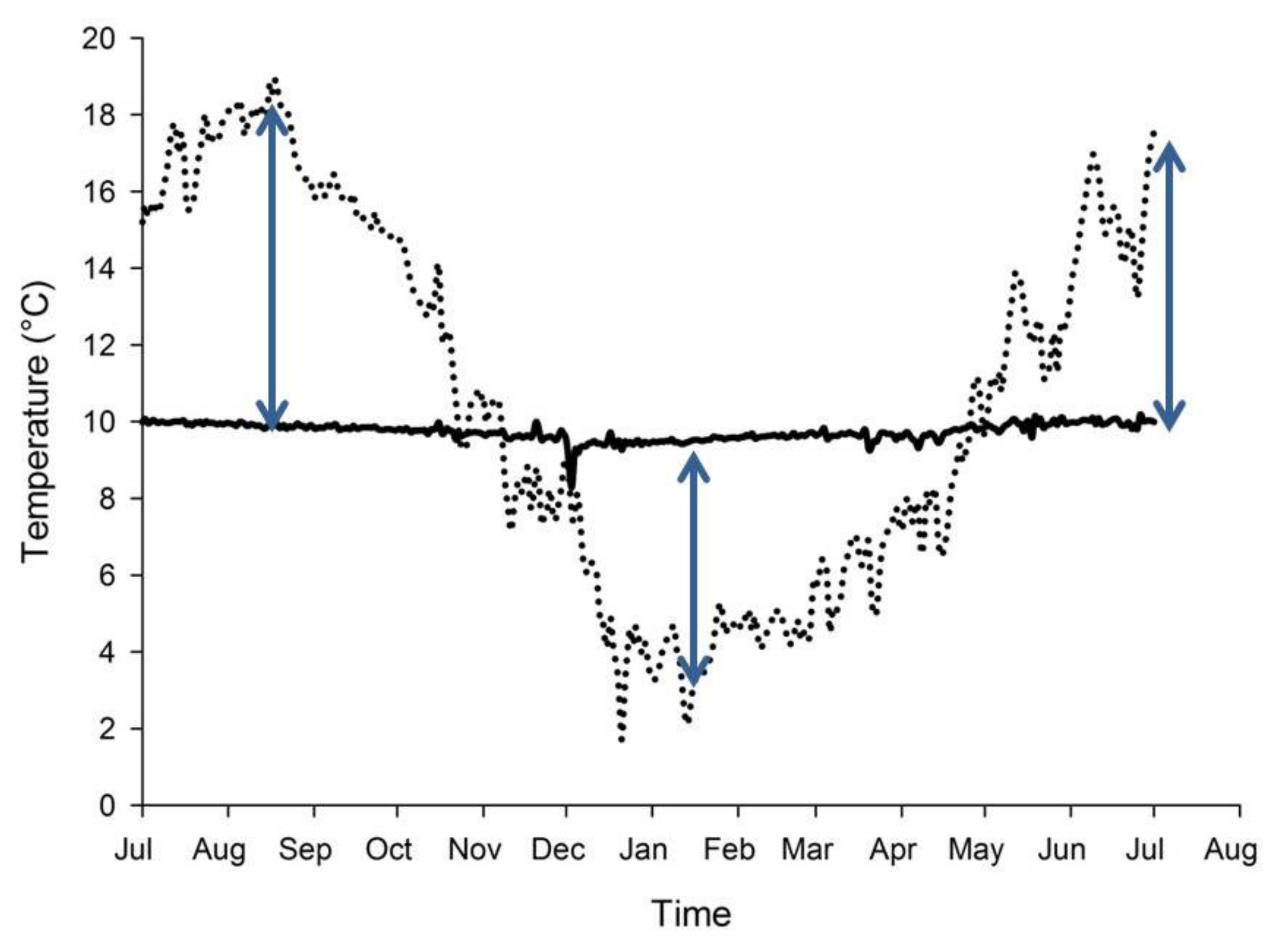

- Nichols, A.L.; Willis, A.D.; Jeffres, C.A.; Deas, M.L. Water Temperature Patterns Below Large Groundwater Springs: Management Implications for Coho Salmon in the Shasta River, California. River Res. Appl. 2013, 30, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, J.; Moyle, P.; Deas, M.; Jeffres, C.; Dahlgren, R.; Kiernan, J.; King, A.; Lusardi, R.; Nichols, A.; Null, S.E.; et al. Baseline Assessment of Physical and Biological Conditions within Waterways on Big Springs Ranch, Siskiyou County, California; California State Water Resources Control Board: Davis, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lapides, D.A.; Manga, M. Large wood as a confounding factor in interpreting the width of spring-fed streams. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2020, 8, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, P.D.; Tanner, C.C. Seasonality of macrophytes and interaction with flow in a New Zealand lowland stream. Hydrobiology 2000, 441, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, A.D.; Nichols, A.L.; Holmes, E.J.; Jeffres, C.A.; Fowler, A.C.; Babcock, C.A.; Deas, M.L. Seasonal aquatic macrophytes reduce water temperatures via a riverine canopy in a spring-fed stream. Freshw. Sci. 2017, 36, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, B.J.F. Hydraulic Habitat of Plants in Streams. Regul. Rivers Res. Manag. 1996, 12, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.D.; Chambers, P.A.; James, W.F.; Koch, E.W.; Westlake, D.F. The interaction between water movement, sediment dynamics and submersed macrophytes. Hydrobiology 2001, 444, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, T.; Biggs, B.J.F. Hydrologic and hydraulic control of macrophyte establishment and performance in streams. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2003, 48, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, B.J.F.; Nikora, V.I.; Snelder, T.H. Linking scales of flow variability to lotic ecosystem structure and function. River Res. Appl. 2005, 21, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, P.; Dunbar, M.; Whitehead, P. Flow controls on lowland river macrophytes: A review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2008, 400, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepf, H.M. Hydrodynamics of vegetated channels. J. Hydraul. Res. 2012, 50, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, R.J.; Champion, P.D.; Nagels, J.W.; Croker, G.F. The Influence of Aquatic Macrophytes on the Hydraulic and Physico-Chemical Properties of a New Zealand Lowland Stream. Hydrobiologia 1999, 416, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffres, C.A.; Nichols, A.L.; Willis, A.D.; Deas, M.L.; Mount, J.F.; Moyle, P.B. Assessment of Restoration Actions on Big Springs Creek, Shasta River, California 2009–2010. National Fish and Wildlife Foundation: Davis, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, K.M.; Gangloff, M.M.; Feminella, J.W. Habitat Modification by the Stream Macrophyte Justicia Americana and Its Effects on Biota. Oecologia 2004, 140, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, T.; Dodds, K.; Kristensen, P.B.; Baisner, A.J. Nitrogen Cycling and Dynamics in a Macrophyte-Rich Stream as Determined by a N-15-Nh4+ Release. Freshw. Biol. 2012, 57, 1579–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, W.W.; Rose, F.L. Influences of Aquatic Macrophytes on Invertebrate Community Structure, Guild Structure, and Microdistribution in Streams. Hydrobiologia 1985, 128, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand-Jensen, K. Influence of submerged macrophytes on sediment composition and near-bed flow in lowland streams. Freshw. Biol. 1998, 39, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklov, A.G.; Greenberg, L.A. Effects of Artificial Instream Cover on the Density of 0+ Brown Trout. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 1998, 5, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg, N.; Jacobsen, D. Feeding Plasticity of 2 Detriviore-Shredders. Freshw. Biol. 1994, 32, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand-Jensen, K.; Vindbaek Madsen, T. Invertebrates Graze Submerged Rooted Macrophytes in Lowland Streams. Oikos 1989, 55, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beland, K.F.; Trial, G.; Kocik, J.F. Use of Riffle and Run Habitats with Aquatic Vegetation by Juvenile Atlantic Salmon. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2004, 24, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.J. Vegetation growth in rivers: Influences upon sediment and nutrient dynamics. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2002, 26, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.C. Velocity and turbulence distribution around lotic macrophytes. Aquat. Ecol. 2005, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepf, H.; Ghisalberti, M. Flow and transport in channels with submerged vegetation. Acta Geophys. 2008, 56, 753–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Webb, B.W.; Ladle, M. Microthermal Gradients and Ecological Implications in Dorset Rivers. Hydrol. Process. 1999, 13, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, A.; Holmes, E. Eye in the Sky: Using UAV Imagery of Seasonal Riverine Canopy Growth to Model Water Temperature. Hydrology 2019, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, A.L.; Lusardi, R.A.; Willis, A.D. Seasonal macrophyte growth constrains extent, but improves quality, of cold-water habitat in a spring-fed river. Hydrol. Process. 2019, 34, 1587–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, P.A.; Prepas, E.E.; Bothwell, M.L.; Hamilton, H.R. Roots versus Shoots in Nutrient Uptake by Aquatic Macrophytes in Flowing Waters. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1989, 46, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, T.V.; Cedergreen, N. Sources of nutrients to rooted submerged macrophytes growing in a nutrient-rich stream. Freshw. Biol. 2002, 47, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Death, R.G.; Winterbourn, M.J. Diversity Patterns in Stream Benthic Invertebrate Communities—The Influence of Habitat Stability. Ecology 1995, 76, 1446–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.A.; Peres-Neto, R.; Olden, J.D. What Controls Who Is Where in Freshwater Fish Communities—The Roles of Biotic, Abiotic, and Spatial Factors. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2001, 58, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, M.P.; Moyle, P.B. Effects of Flow Regime on Fish Assemblages in a Regulated California Stream. Ecol. Appl. 2001, 11, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamuro, A.M. Aquatic Insect Adaptations to Different Flow Regimes. Ph.D.’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lytle, D.A. Flash Floods and Aquatic Insect Life-History Evolution: Evaluation of Multiple Models. Ecology 2002, 83, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, D.A.; Poff, N. Adaptation to natural flow regimes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, D.A.; Olden, J.D.; McMullen, L.E. Drought-Escape Behaviors of Aquatic Insects Maybe Adaptations to Highly Variable Flow Regimes Characteristic of Desert Rivers. Southwest. Nat. 2008, 53, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füreder, L.; Schütz, C.; Wallinger, M.; Burger, R. Physico-chemistry and aquatic insects of a glacier-fed and a spring-fed alpine stream. Freshw. Biol. 2001, 46, 1673–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquín, J.; Death, R.G. Spatial patterns of macroinvertebrate diversity in New Zealand springbrooks and rhithral streams. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2006, 25, 768–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquin, J.; Death, R.G. Patterns of Invertebrate Diversity in Streams and Freshwater Springs in Northern Spain. Arch. Hydrobiol. 2004, 161, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B.J.; Hobbie, J.E.; Corliss, T.L.; Kriet, K. A continuous-flow periphyton bioassay: Tests of nutrient limitation in a tundra stream1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1983, 28, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, A.E.; Hiltner, A.L.; Hullar, M.A.J.; Miller, M.C.; Vestal, J.R.; Peterson, B.J. Nutrient Influence on a Stream Grazer—Orthocladius Microcommunities Respond to Nutrient Input. Ecology 1988, 69, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundie, J.H.; Simpson, K.S.; Perrin, C.J. Respones of Stream Periphyton and Benthic Insects to Increaes in Dissolved Inorganic Phosphorus in a Mesocosm. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1991, 48, 2061–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, C.J.; Richardson, J.S. N and P Limitation of Benthos Abundance in the Nechako River, British Columbia. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1997, 54, 2574–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusven, M.A.; Meehan, W.R.; Biggam, R.C. The role of aquatic moss on community composition and drift of fish-food organisms. Hydrobiology 1990, 196, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shupryt, M.P.; Stelzer, R.S. Macrophyte beds contribute disproportionately to benthic invertebrate abundance and biomass in a sand plains stream. Hydrobiology 2009, 632, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, D.J.; Gotelli, N.J. Effects of disturbance frequency, intensity, and area on assemblages of stream macroinvertebrates. Oecologia 2000, 124, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menge, B.A. Organization of New England Rocky Intertidal Community—Role of Predation, Competition, and Environemtnal Heterogeneity. Ecol. Monogr. 1976, 46, 355–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckarsky, B.L. Predator-Prey Interactions between Stoneflies and Mayflies: Behavioral Observations. Ecology 1980, 61, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.H. Diversity in Tropical Rain Forests and Coral Reefs—High Diversity of Trees and Corals Is Maintained Only in a Non-Equillibrium State. Science 1978, 199, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resh, V.H.; Brown, A.V.; Covich, A.P.; Gurtz, M.E.; Li, H.W.; Minshall, G.W.; Reice, S.R.; Sheldon, A.L.; Wallace, J.B.; Wissmar, R.C. The Role of Disturbance in Stream Ecology. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 1988, 7, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minshall, G.W. Community dynamics of the benthic fauna in a woodland springbrook. Hydrobiology 1968, 32, 305–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laperriere, J.D. Benthic ecology of a spring-fed river of interior Alaska. Freshw. Biol. 1994, 32, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, C.R.; Scarsbrook, M.R.; Dolédec, S. The intermediate disturbance hypothesis, refugia, and biodiversity in streams. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1997, 42, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquín, J.; Death, R.G. Downstream changes in spring-fed stream invertebrate communities: The effect of increased temperature range? J. Limnol. 2011, 70, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huston, M. A General Hypothesis of Species Diversity. Am. Nat. 1979, 113, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D. Community Ecology: Is It Time to Move On? Am. Nat. 2004, 163, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minshall, G.W.; Petersen, R.C.; Nimz, C.F. Species Richness in Streams of Different Size from the Same Drainage Basin. Am. Nat. 1985, 125, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, C. Natural History of the Quinnat Salmon; 80: Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhards, S.V. Biological Notes on Precocious Male Chinook Salmon Parr in the Salmon River Drainage, Idaho. Progress. Fish Culturist 1960, 22, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffres, C.A.; Adams, C.C. Novel life history tactic observed in fall-run Chinook Salmon. Ecology 2019, 100, e02733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, M.J.; Quinn, T.P.; Kinnison, M.T.; Boustead, N.C. Divergence in Juvenile Growth and Life History in Two Recently Colonized and Partially Isolated Chinook Salmon Populations. J. Fish Biol. 2000, 57, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovtang, J.C. Distribution, Habitat Use and Growth of Juvenile Chinook Salmon in the Metolius River Basin, Oregon. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, R.S.; Letcher, B.H.; Nislow, K.H. Drivers of growth variation in juvenile Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): An elasticity analysis approach. J. Anim. Ecol. 2010, 79, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, P.S.; Gilvear, D.J.; Armstrong, J.D. Variation in performance reveals discharge-related energy costs for foraging Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) parr. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2006, 15, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayllón, D.; Nicola, G.G.; Elvira, B.; Parra, I.; Almodóvar, A. Thermal Carrying Capacity for a Thermally-Sensitive Species at the Warmest Edge of Its Range. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwood, J.W.; Waters, T.F. Effects of Floods on Food Consumption and Production Rates of a Stream Brook Trout Population. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1969, 98, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagrodski, A.; Raby, G.D.; Hasler, C.T.; Taylor, M.K.; Cooke, S.J. Fish stranding in freshwater systems: Sources, consequences, and mitigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 103, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapointe, M.; Eaton, B.; Driscoll, S.; Latulippe, C. Modelling the Probability of Salmonid Egg Pocket Scour Due to Floods. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2000, 57, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.; Kolmes, S.A. Maximum Temperature Limits for Chinook, Coho, and Chum Salmon, and Steelhead Trout in the Pacific Northwest. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2005, 13, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunjak, R.A. Physiological Consequences of Overwintering in Streams: The Cost of Acclimitization? Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1988, 45, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, W.J. Redd Superimposition and Egg Capacity of Pink Salmon Spawning Beds. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1964, 21, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, P.W.; Logerwell, E.A.; Mantua, N.J.; Francis, R.C.; Agostini, V.N. Environmental factors influencing freshwater survival and smolt production in Pacific Northwest coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2004, 61, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.J.; Johnsen, B.O. The functional relationship between peak spring floods and survival and growth of juvenile Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) and Brown Trout (Salmo trutta). Funct. Ecol. 1999, 13, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattanéo, F.; Lamouroux, N.; Breil, P.; Capra, H. The influence of hydrological and biotic processes on brown trout (Salmo trutta) population dynamics. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2002, 59, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unfer, G.; Hauer, C.; Lautsch, E. The influence of hydrology on the recruitment of brown trout in an Alpine river, the Ybbs River, Austria. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2010, 20, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, I.; Maekawa, K. Metapopulation structure of stream-dwelling Dolly Varden charr inferred from patterns of occurrence in the Sorachi River basin, Hokkaido, Japan. Freshw. Biol. 2004, 49, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustard, D.R.; Narver, D.W. Aspects of the Winter Ecology of Juvenile Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) and Steelhead Trout (Salmo gairdneri). J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1975, 32, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, H.H.; Hodgson, G.R.; Harvey, B.C.; Roche, M.F. Distribution of Juvenile Coho Salmon in Relation to Water Temperatures in Tributaries of the Mattole River, California. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2001, 21, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.M.; Hurley, M. A new energetics model for brown trout, Salmo trutta. Freshw. Biol. 1999, 42, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojanguren, A.; Braña, F. Thermal dependence of embryonic growth and development in brown trout. J. Fish Biol. 2003, 62, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.W.; Griffith, J.S. Survival of Rainbow Trout during Their 1st Winter in the Henrys Fork of the Snake River, Idaho. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1994, 123, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, D.A.; Young, R.G. Significance of river–aquifer interactions for reach-scale thermal patterns and trout growth potential in the Motueka River, New Zealand. Hydrogeol. J. 2008, 17, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, W.R.; Adams, C.C.; Crombie, W.B.; Langendorf, H.D.; Stenhouse, S.A.; Kirkby, K.M. Shasta River Juvenile Coho Habitat & Migration Study; 141: CA Dept. of Fish and Wildlife, Prepared for U.S. Bureau of Reclamation; California Department of Fish and Wildlife, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: Yreka, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Null, S.E.; Lund, J.R. Fish Habitat Optimization to Prioritize River Restoration Decisions. River Res. Appl. 2011, 28, 1378–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, N.T.; Perrin, C.J.; Slaney, P.A.; Ward, B.R. Increased Juvenile Salmonid Growth by Whole-River Fertilization. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1990, 47, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausch, K.D.; White, R.J. Compeition between Brook Trout (Salvelinus Fontinalis) and Brown Trout (Salmo Trutta) for Positions in a Michigan Stream. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1981, 38, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, R.A. Foragin Behavior of Free Ranging Wild and Hatchery Brown Trout in a Stream. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1984, 113, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausch, K.D. Profitable stream positions for salmonids: Relating specific growth rate to net energy gain. Can. J. Zool. 1984, 62, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everest, F.H.; Chapman, D.W. Habitat Selection and Spatial Interaction by Juvenile Chinook Salmon and Steelhead Trout in Two Idaho Streams. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1972, 29, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.E.; Hartman, G.F. Influence of Cover Complexity and Current Velocity on Winter Habitat Use by Juvenile Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1989, 46, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonzarich, D.G.; Quinn, T.P. Experimental evidence for the effect of depth and structure on the distribution, growth, and survival of stream fishes. Can. J. Zool. 1995, 73, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culp, J.M.; Scrimgeour, G.J.; Townsend, G.D. Simulated Fine Woody Debris Accumulations in a Stream Increase Rainbow Trout Fry Abundance. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1996, 125, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand, T.C.; Dill, L.M. The Energetic Equivalence of Cover to Juvenile Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus Kisutch): Ideal Free Distribution Theory Applied. Behav. Ecol. 1997, 8, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, W.D.; Pawson, M.G.; Quayle, V.; Ives, M.J. The effects of stream canopy management on macroinvertebrate communities and juvenile salmonid production in a chalk stream. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2009, 16, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggenes, J.; Krog, O.M.W.; Lindas, O.R.; Dokk, J.G.; Bremnes, T. Homostatic Behavioral Responses in a Changing Environment—Brown Trout (Salmo Trutta) Become Nocturnal During Winter. J. Anim. Ecol. 1993, 62, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MakiPetays, A.; Muotka, T.; Huusko, A.; Tikkanen, P.; Kreivi, P. Seasonal Changes in Habitat Use and Preference by Juvenile Brown Trout, Salmo Trutta, in a Northern Boreal River. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1997, 54, 520–530. [Google Scholar]

- Sundbaum, K.; Naslund, I. Effects of Woody Debris on the Growth and Behaviour of Brown Trout in Experimental Stream Channels. Can. J. Zool. Rev. Can. Zool. 1998, 76, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, O.; Grant, J.W.; Noël, M.V.; Kim, J.-W. Mechanisms underlying the increase in young-of-the-year Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) density with habitat complexity. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2008, 65, 1956–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, K.M.; Dibattista, J.D.; Thomas, J.B. Physiological Causes and Consequences of Social Status in Salmonid Fish. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2005, 45, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, J.F.; Stachowicz, J.J.; Bertness, M.D. Inclusion of facilitation into ecological theory. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.H.; Hayes, S.A.; Hanson, C.V.; Macfarlane, R.B. Marine survival of steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) enhanced by a seasonally closed estuary. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2008, 65, 2242–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beakes, M.P.; Satterthwaite, W.; Collins, E.M.; Swank, D.R.; Merz, J.E.; Titus, R.G.; Sogard, S.M.; Mangel, M. Smolt Transformation in Two California Steelhead Populations: Effects of Temporal Variability in Growth. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2010, 139, 1263–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, D.E.; Hilborn, R.; Chasco, B.; Boatright, C.P.; Quinn, T.P.; Rogers, L.; Webster, M.S. Population diversity and the portfolio effect in an exploited species. Nature 2010, 465, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, B.L. Risk-Based Reanalysis of the Effects of Climate Change on U.S. Cold-water Habitat. Clim. Change 2006, 76, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhoe, K.; Cayan, D.; Field, C.B.; Frumhoff, P.C.; Maurer, E.P.; Miller, N.L.; Moser, S.C.; Schneider, S.H.; Cahill, K.N.; Cleland, E.E.; et al. Emissions pathways, climate change, and impacts on California. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 12422–12427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, I.T.; Cayan, D.R.; Dettinger, M.D. Changes toward Earlier Streamflow Timing across Western North America. J. Clim. 2005, 18, 1136–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Dettinger, M.D.; Cayan, D.R.; Hidalgo, H.G. Potential increase in floods in California’s Sierra Nevada under future climate projections. Clim. Change 2011, 109, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, P.B.; Kiernan, J.D.; Crain, P.K.; Quiñones, R.M. Climate Change Vulnerability of Native and Alien Freshwater Fishes of California: A Systematic Assessment Approach. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tague, C.; Grant, G.E. Groundwater dynamics mediate low-flow response to global warming in snow-dominated alpine regions. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Null, S.E.; Viers, J.H.; Mount, J.F. Hydrologic Response and Watershed Sensitivity to Climate Warming in California’s Sierra Nevada. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Null, S.E.; Viers, J.H.; Deas, M.L.; Tanaka, S.K.; Mount, J.F. Stream temperature sensitivity to climate warming in California’s Sierra Nevada: Impacts to coldwater habitat. Clim. Change 2012, 116, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M. Hydrology of Spring-Dominated Streams in the Oregon Cascades. Water Resour. Res. 1996, 32, 2435–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tague, C.; Grant, G.; Farrell, M.; Choate, J.; Jefferson, A. Deep groundwater mediates streamflow response to climate warming in the Oregon Cascades. Clim. Change 2007, 86, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörösmarty, C.J.; McIntyre, P.B.; Gessner, M.O.; Dudgeon, D.; Prusevich, A.; Green, P.; Glidden, S.; Bunn, S.E.; Sullivan, C.A.; Liermann, C.R.; et al. Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 2010, 467, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howat, I.M.; Tulaczyk, S.; Rhodes, P.; Israel, K.; Snyder, M. A precipitation-dominated, mid-latitude glacier system: Mount Shasta, California. Clim. Dyn. 2006, 28, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Railsback, S.F.; Rose, K.A. Bioenergetics Modeling of Stream Trout Growth: Temperature and Food Consumption Effects. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1999, 128, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannote, R.L.; Minshall, G.W.; Cummins, K.W.; Sedell, J.R.; Cushing, C.E. River Continuum Concept. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1980, 37, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W.P.; Bayley, P.B.; Sparks, R.E. The Flood Pulse Concept in River—Floodplain Systems. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1989, 106, 110–127. [Google Scholar]

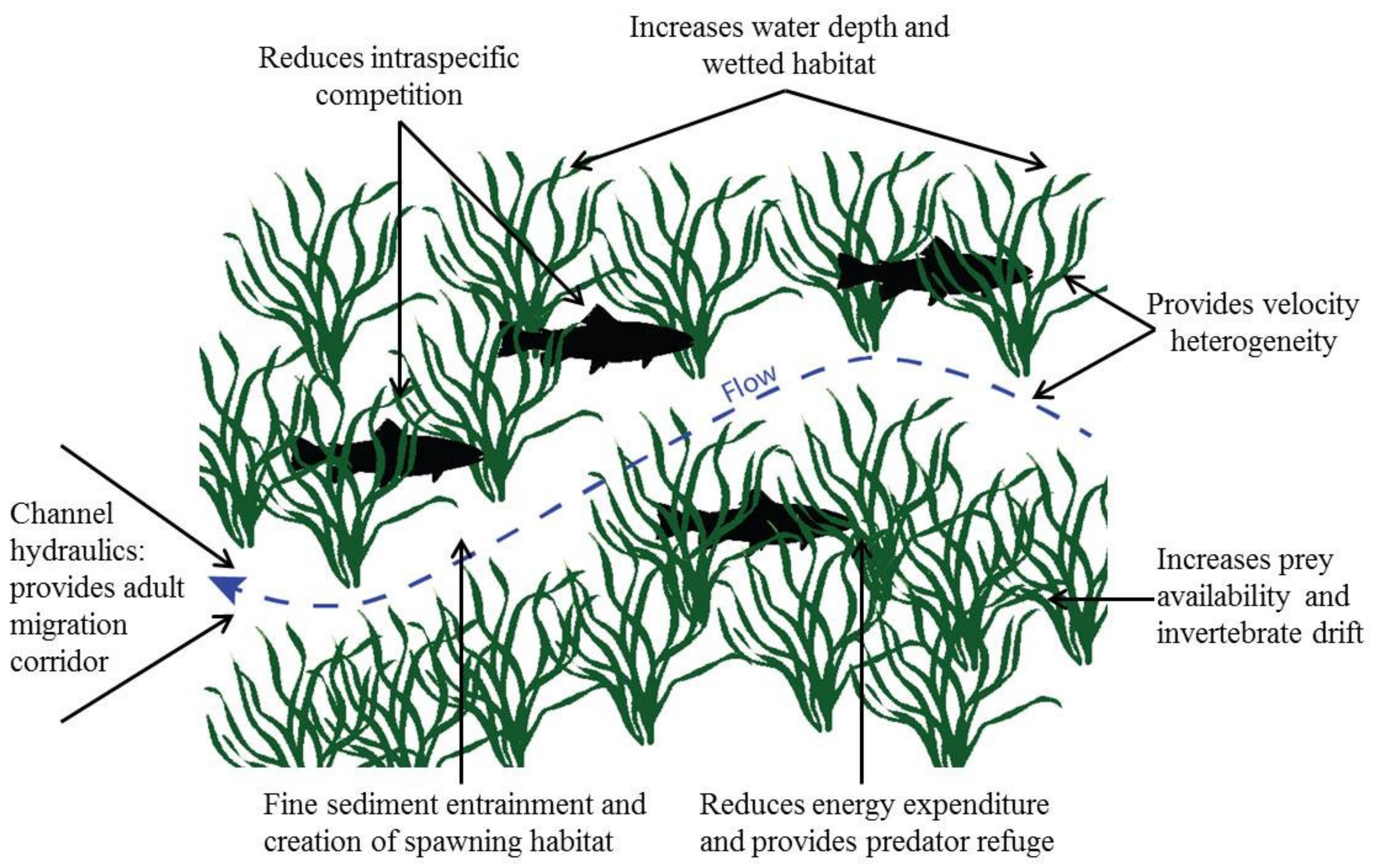

| Type of Effect | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Abiotic | Reduce water velocity | [53] |

| Increase stream depth | [53] | |

| Increase cross-sectional area and wetted habitat | [45] | |

| Modification of channel hydraulics | [54] | |

| Reduce water temperature through shading | [46] | |

| Enhance streambed stability | [55] | |

| Contribute to nutrient cycling | [56] | |

| Biotic | Provide habitat for epiphytes, inverts. and fishes | Various |

| Velocity heterogeneity and refuge for organisms | [57] | |

| Retain fine sediment and organic matter | [58] | |

| Increase prey availability for consumers | [7] | |

| Increase invertebrate drift rates | [7] | |

| Provide predator refuge | [59] | |

| Food resource for detritivores | [60] | |

| Food resource for herbivores | [61] | |

| Provide habitat complexity and heterogeneity | [57] | |

| Provide habitat cover for fish | [62] | |

| Increase invertebrate richness and density | [57] | |

| Increase fish density | [59] | |

| Reduce intraspecific competition in fish | [59] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lusardi, R.A.; Nichols, A.L.; Willis, A.D.; Jeffres, C.A.; Kiers, A.H.; Van Nieuwenhuyse, E.E.; Dahlgren, R.A. Not All Rivers Are Created Equal: The Importance of Spring-Fed Rivers under a Changing Climate. Water 2021, 13, 1652. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13121652

Lusardi RA, Nichols AL, Willis AD, Jeffres CA, Kiers AH, Van Nieuwenhuyse EE, Dahlgren RA. Not All Rivers Are Created Equal: The Importance of Spring-Fed Rivers under a Changing Climate. Water. 2021; 13(12):1652. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13121652

Chicago/Turabian StyleLusardi, Robert A., Andrew L. Nichols, Ann D. Willis, Carson A. Jeffres, A. Haven Kiers, Erwin E. Van Nieuwenhuyse, and Randy A. Dahlgren. 2021. "Not All Rivers Are Created Equal: The Importance of Spring-Fed Rivers under a Changing Climate" Water 13, no. 12: 1652. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13121652

APA StyleLusardi, R. A., Nichols, A. L., Willis, A. D., Jeffres, C. A., Kiers, A. H., Van Nieuwenhuyse, E. E., & Dahlgren, R. A. (2021). Not All Rivers Are Created Equal: The Importance of Spring-Fed Rivers under a Changing Climate. Water, 13(12), 1652. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13121652