Biodiversity and Habitat Assessment of Coastal Benthic Communities in a Sub-Arctic Industrial Harbor Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

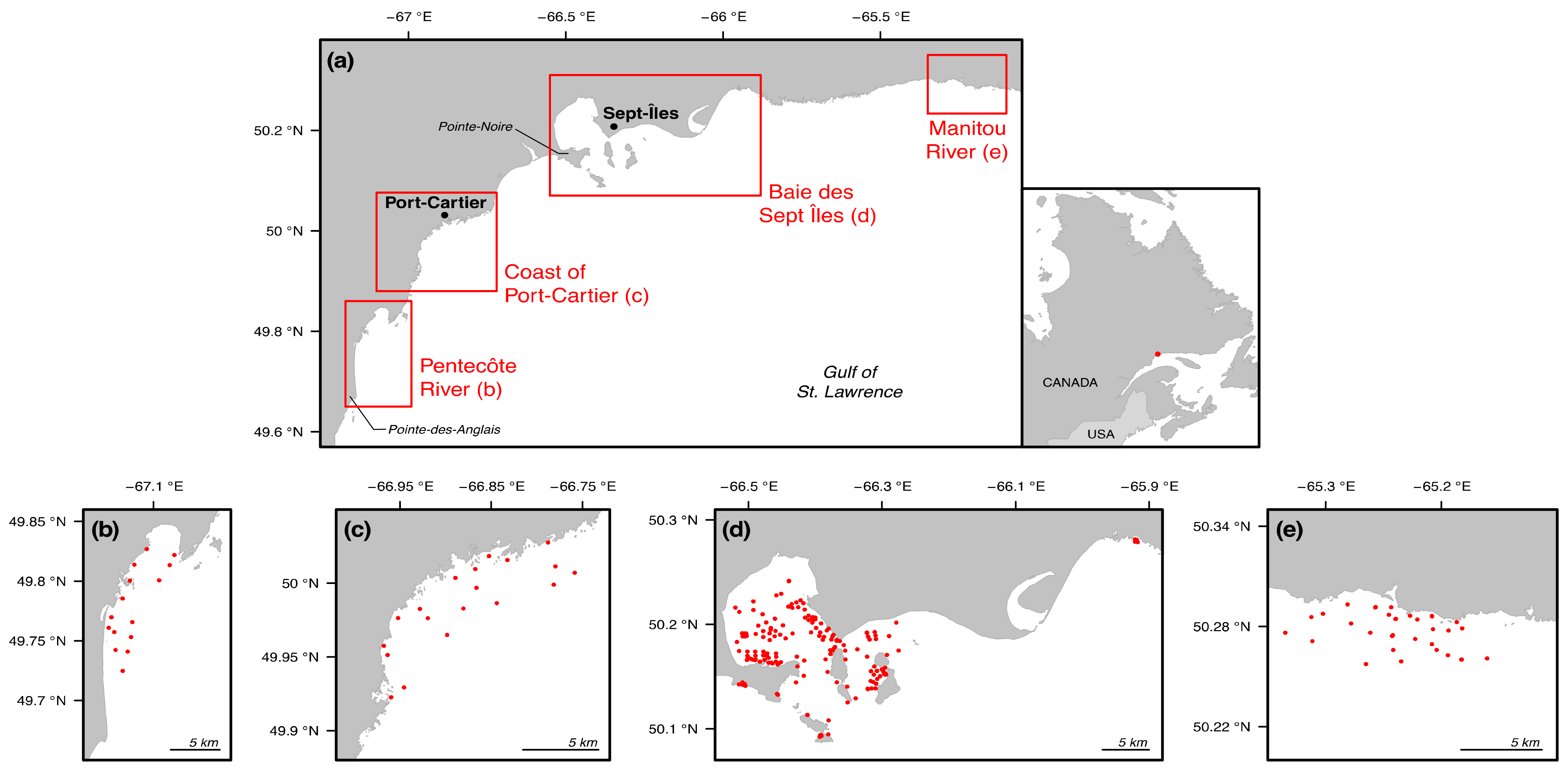

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Laboratory Work

2.3.1. Habitat Parameters

2.3.2. Biological Samples

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Description of the Ecosystems

3.1.1. Sediment Parameters

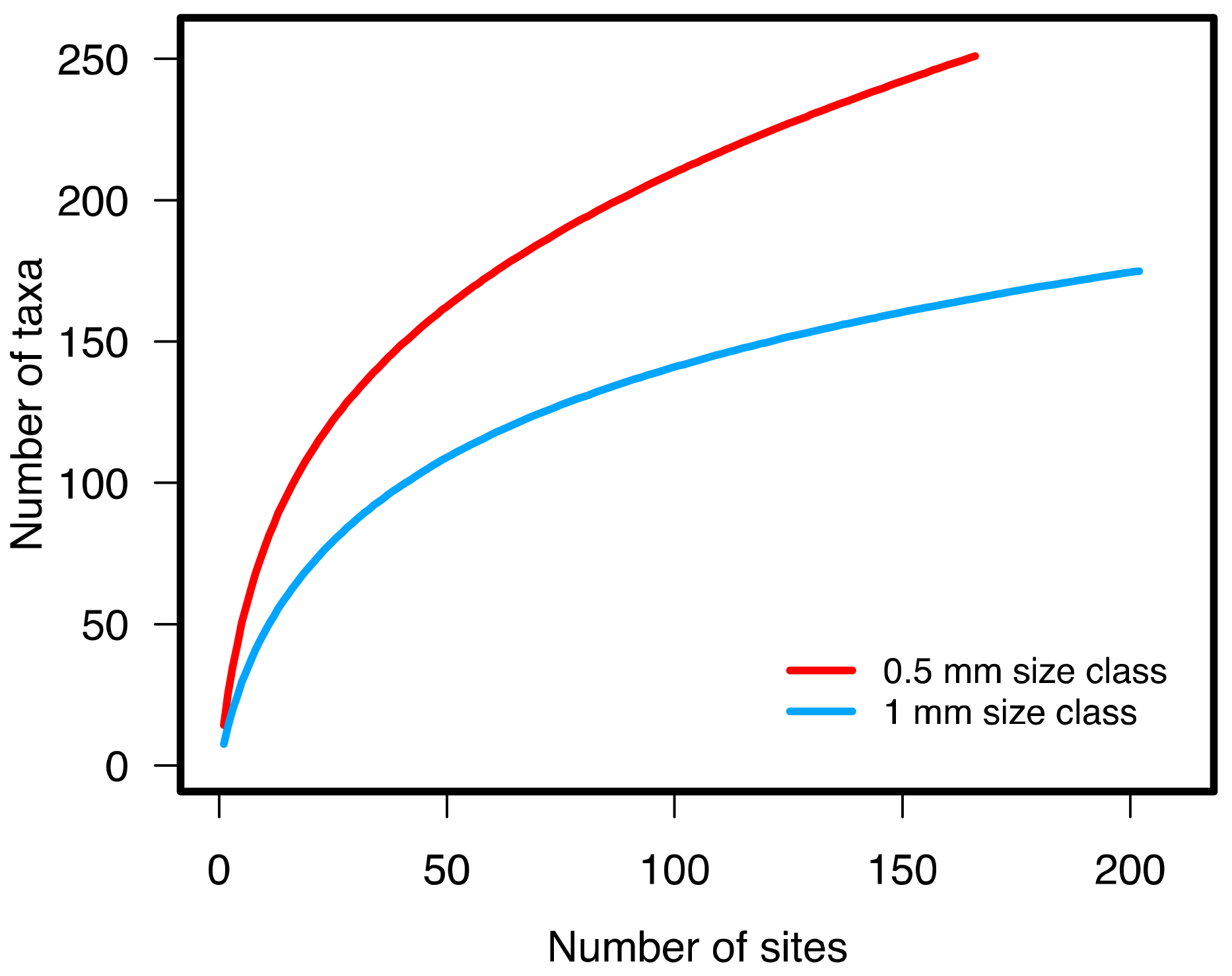

3.1.2. Benthic Community

3.2. Similarity between Taxa Assemblages

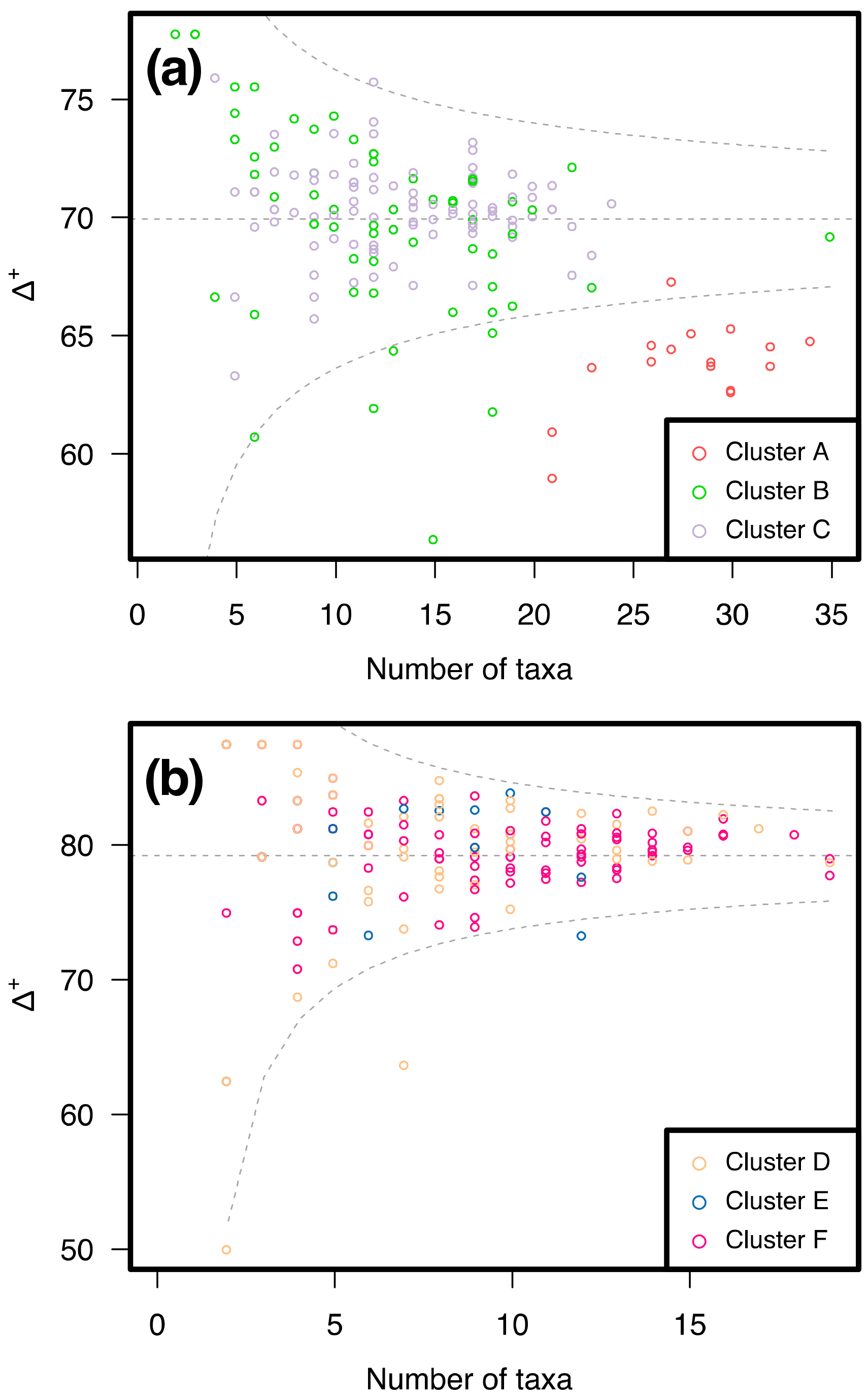

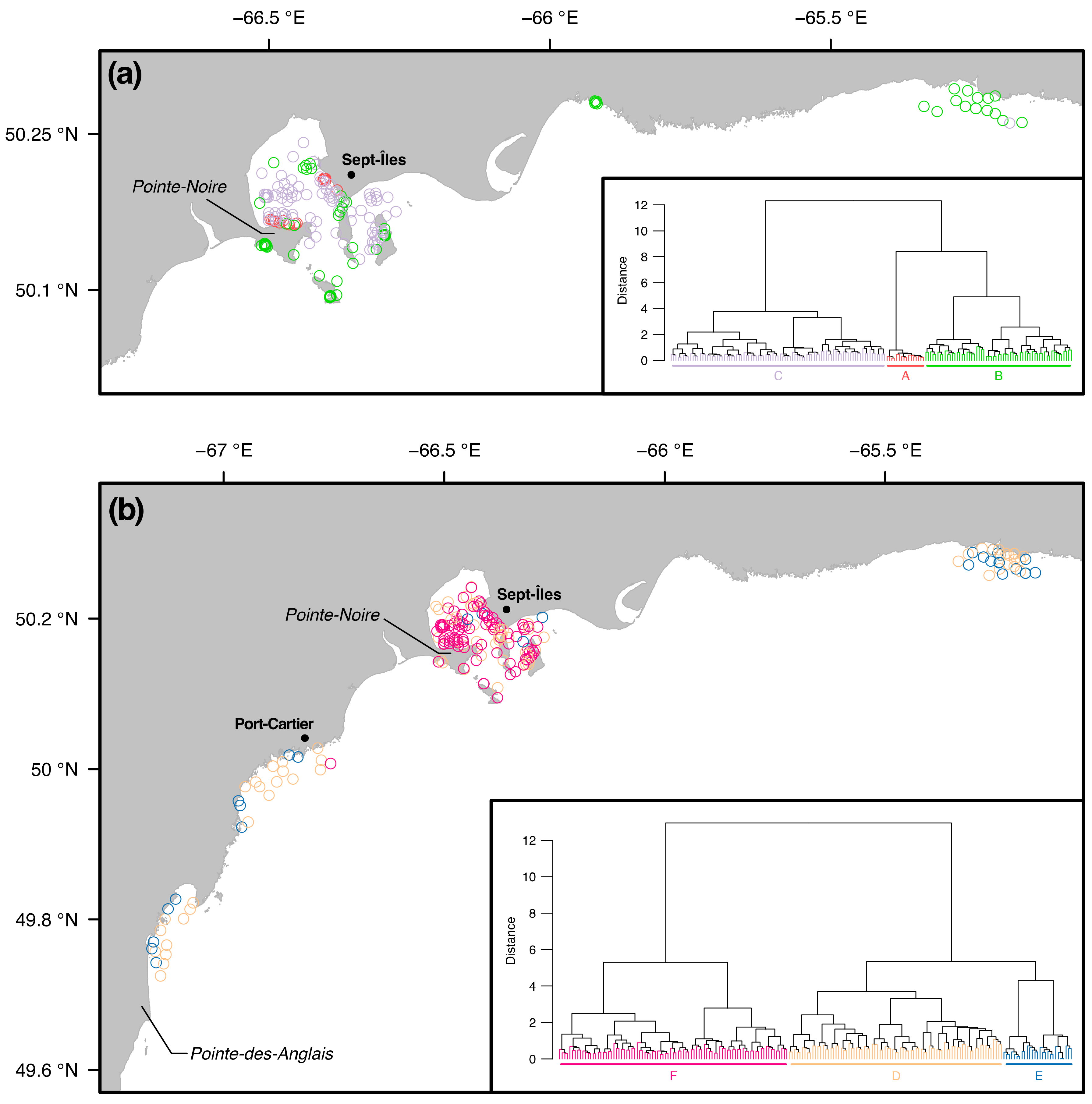

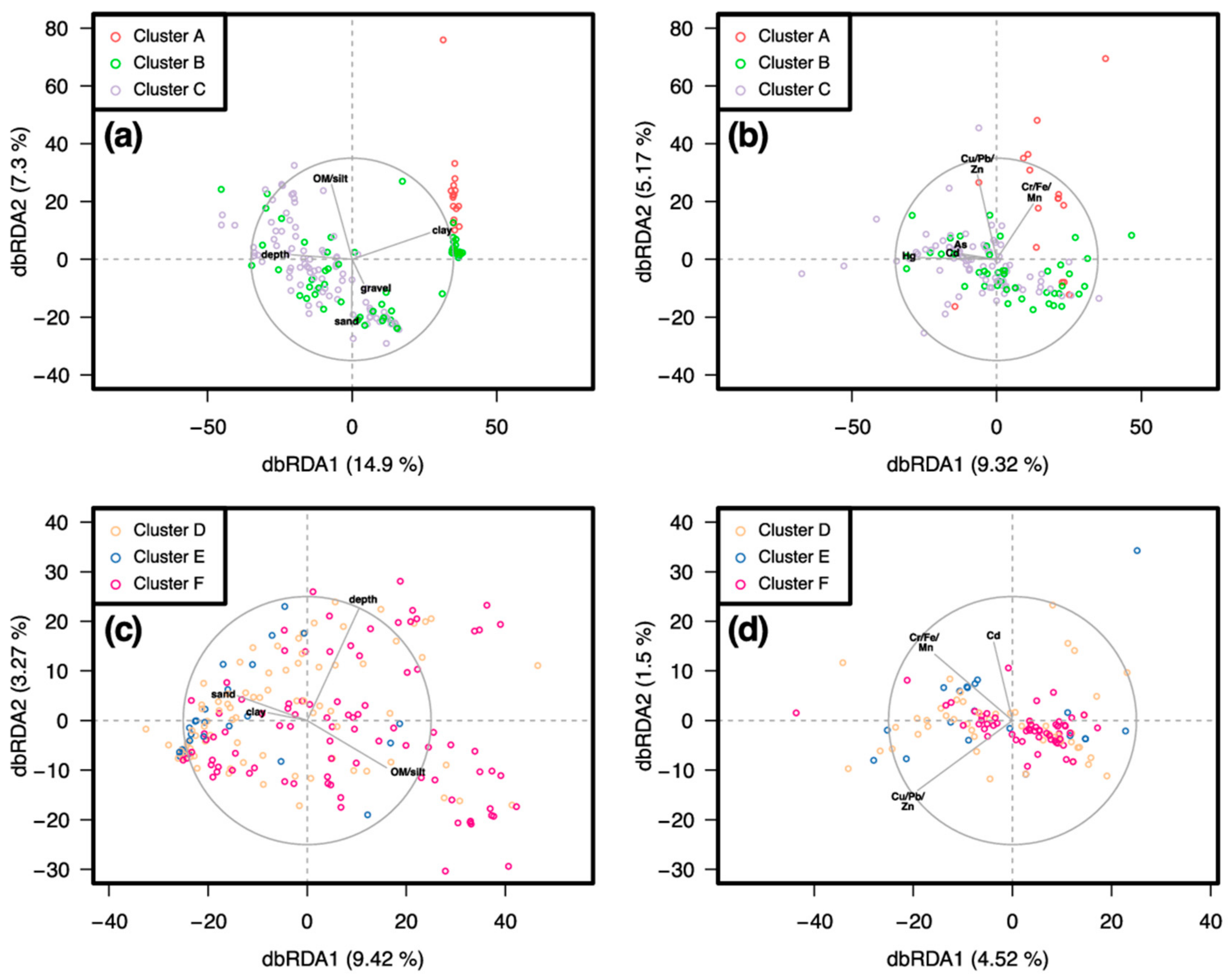

3.2.1. 0.5 mm Size Class

3.2.2. 1 mm Size Class

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Data and Code Availability

References

- Halpern, B.S.; Frazier, M.; Afflerbach, J.; Lowndes, J.S.; Micheli, F.; O’Hara, C.; Scarborough, C.; Selkoe, K.A. Recent pace of change in human impact on the world’s ocean. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, B.S.; Selkoe, K.A.; Micheli, F.; Kappel, C.V. Evaluating and ranking the vulnerability of global marine ecosystems to anthropogenic threats. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, T.H.; Rosenberg, R. Macrobenthic succession in relation to organic enrichment and pollution of the marine environment. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 1978, 16, 229–311. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, E.; Knowlton, N. Global marine biodiversity trends. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, K.; Botsford, L.W.; Ciannelli, L.; Fogarty, M.J.; Heath, M.; Planque, B.; Shannon, L.J.; Wieland, K. Human impacts on marine ecosystems. In Marine Ecosystems and Global Change; Barange, M., Field, J.G., Harris, R.P., Hofmann, E.E., Perry, R.I., Werner, F.E., Ashby, D.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Piot, A.; Nozais, C.; Archambault, P. Meiofauna affect the macrobenthic biodiversity-ecosystem functioning relationship. Oikos 2014, 123, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edie, S.M.; Jablonski, D.; Valentine, J.W. Contrasting responses of functional diversity to major losses in taxonomic diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoste, É.; Piot, A.; Archambault, P.; McKindsey, C.W.; Nozais, C. Bioturbation activity of three macrofaunal species and the presence of meiofauna affect the abundance and composition of benthic bacterial communities. Mar. Environ. Res. 2018, 136, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Biological Diversity. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-en.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/news/communications-material (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Brown, C.J.; Saunders, M.I.; Possingham, H.P.; Richardson, A.J. Interactions between global and local stressors of ecosystems determine management effectiveness in cumulative impact mapping. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, Á.; Dauer, D.M.; Grémare, A. The importance of setting targets and reference conditions in assessing marine ecosystem quality. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvin, J.C.; Ruellet, T.; Desroy, N.; Janson, A.-L. The ecological quality status of the Bay of Seine and the Seine estuary: Use of biotic indices. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2007, 55, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, D.R.; Lohrer, A.M.; Pilditch, C.A.; Thrush, S.F. Changes in ecosystem function across sedimentary gradients in Estuaries. Ecosystems 2014, 17, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largaespada, C.; Guichard, F.; Archambault, P. Meta-ecosystem engineering: Nutrient fluxes reveal intraspecific and interspecific feedbacks in fragmented mussel beds. Ecology 2012, 93, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, H.; Piepenburg, D.; Archambault, P. Are hotspots always hotspots? The relationship between diversity, resource and ecosystem functions in the Arctic. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belley, R.; Snelgrove, P.V.R.; Archambault, P.; Juniper, S.K. Environmental drivers of benthic flux variation and ecosystem functioning in Salish Sea and Northeast Pacific sediments. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, J.R.; Demopoulos, A.W.J. The influence of different deep-sea coral habitats on sediment macrofaunal community structure and function. PeerJ 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauer, D.M. Biological criteria, environmental health and estuarine macrobenthic community structure. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1993, 26, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, A.; Franco, J.; Pérez, V. A marine Biotic Index to establish the ecological quality of soft-bottom benthos within European estuarine and coastal environments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 1100–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriou, A.; McIntyre, A. Methods for the Study of Marine Benthos, 3rd ed.; Eleftheriou, A., McIntyre, A., Eds.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2005; p. 418. ISBN 0632054883. [Google Scholar]

- McKindsey, C.W.; Bourget, E. Body size and spatial variation of community structure in subarctic intertidal boulder fields. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 216, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, J.D.; Hughes, D.J.; Gonzalez-Vecino, J.L. Sieve size influence in estimating biomass, abundance and diversity in samples of deep-sea macrobenthos. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002, 225, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, T.; Patrício, J.; Neto, J.M.; Ceia, F.R.; Franco, J.; Marques, J.C. The influence of mesh size in environmental quality assessment of estuarine macrobenthic communities. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 1162–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belley, R.; Archambault, P.; Sundby, B.; Gilbert, F.; Gagnon, J.M. Effects of hypoxia on benthic macrofauna and bioturbation in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada. Cont. Shelf Res. 2010, 30, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigle, R.M.; Archambault, P.; Halpern, B.S.; Lowndes, J.S.; Côté, I.M. Incorporating public priorities in the ocean health index: Canada as a case study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schloss, I.; Archambault, P.; Beauchesne, D.; Bourgault, D.; Cusson, M.; Dumont, D.; Ferreyra, G.; Levasseur, M.; Pelletier, É.; St-Louis, R.; et al. Impacts potentiels cumulés des facteurs de stress liés aux activités humaines sur l’écosystème marin du Saint-Laurent. In Les Hydrocarbures Dans le Golfe du Saint-Laurent—Enjeux Sociaux, Economiques et Environnementaux; Archambault, P., Schloss, I., Grant, C., Plante, S., Eds.; Notre Golfe: Rimouski, QC, Canada, 2017; pp. 132–165. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Shipping in Canada: 2011; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Update of Stock Status Indicators for Northern Shrimp in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence; Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Demers, K.A.; le Hénaff, A.; Carrière, J. État des glaces. In Observatoire Environnemental de la Baie de Sept-Îles; Carrière, J., Ed.; INREST: Sept-Îles, QC, Canada, 2018; pp. 593–612. [Google Scholar]

- Dutil, J.-D.; Proulx, S.; Galbraith, P.S.; Chasse, J.; Lambert, N.; Laurian, C. Coastal and epipelagic habitats of the estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2012, 3009, 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J.-L.; Bourgault, D.; Dumont, D. Hydrodynamique de la Baie de Sept-Îles. Master’s Thesis, Université du Québec à Rimouski, Rimouski, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, B.E. Loss-on-Ignition as an estimate of soil organic matter. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1974, 38, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, C.K. A Scale of grade and class terms for clastic sediments. J. Geol. 1922, 30, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L. Petrology of Sedimentary Rocks, 2nd ed.; Hemphill Publishing Company: Austin, TX, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Centre d’Expertise en Analyse Environnementale du Québec. Détermination des Métaux: Méthode par Spectrométrie de Masse à Source Ionisante au Plasma D’argon; MA. 200—Mét 1.2, Rév 5; Ministère du Développement Durable de L’environnement et de la Lutte contre les Changements Climatiques du Québec: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Environment Canada and Ministère du Développement Durable de l’environnement et des Parcs du Québec. Criteria for the Assessment of Sediment Quality in Quebec and Application Frameworks: Prevention, Dredging and Remediation; Environment Canada and Ministère du Développement Durable de l’environnement et des Parcs du Québec: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, M.R.T.; Fortin, M.-J. Spatial Analysis: A Guide for Ecologists, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Register of Marine Species. Available online: http://marinespecies.org (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. PRIMER v6: User Manual/Tutorial; Primer-E Ltd.: Albany, AK, New Zealand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, A. Estimating the population size for capture-recapture data with unequal catchability. Biometrics 1987, 43, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotelli, N.J.; Colwell, R.K. Quantifying biodiversity: Procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol. Lett. 2001, 4, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, R.M.; Clarke, K.R. New ‘biodiversity’ measures reveal a decrease in taxonomic distinctness with increasing stress. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1995, 129, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. A taxonomic distinctness index and its statistical properties. J. Appl. Ecol. 1998, 35, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Borcard, D.; Peres-Neto, P.R. Analyzing beta diversity: Partitioning the spatial variation of community composition data. Ecol. Monogr. 2005, 75, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E.; McGill, B.J. Biological Diversity: Frontiers in Measurement and Assessment, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Legendre, P.; Legendre, L.F.J. Numerical Ecology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrêne, M.; Legendre, P. Species assemblages and indicator species: The need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol. Monogr. 1997, 67, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, G.P.; Keough, M.J. Experimental Design and Data Analysis for Biologists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, R.D. Detection of Influential Observation in Linear Regression. Technometrics 1977, 19, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.; Ripley, B. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle, B.H.; Anderson, M.J. Fitting multivariate models to community data: A comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology 2001, 82, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Louis, R.; Montero-Serrano, J.-C.; Archambault, P.; Dreujou, E.; Carrière, J. Qualité des sédiments. In Observatoire Environnemental de la Baie de Sept-Îles; Carrière, J., Ed.; INREST: Sept-Îles, QC, Canada, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 213–376. ISBN 9782981763600. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Nagler, J.J.; Fournier, M.; Lebeuf, M.; Cyr, D.G. Toxicological characterization of sediments from Baie des Anglais on the St. Lawrence Estuary. Chemosphere 1999, 39, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocean Biodiversity Integration System. Available online: https://obis.org (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Brunel, P.; Bossé, L.; Lamarche, G. Catalogue of the Marine Invertebrates of the Estuary and Gulf of Saint Lawrence; Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries, Aquatic Sciences; NRC Research Press: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Simard, N.; Pereira, S.; Estrada, R.; Nadeau, M. État de la situation des espèces envahissantes marines du Québec. In Rapport Manuscrit Canadien des Sciences Halieutiques et Aquatiques; Fisheries and Oceans Canada: Mont-Joli, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.S.; Elliott, M. Ecology of Marine Sediments: From Science to Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Levinton, J.S. Marine Biology: Function, Biodiversity, Ecology, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Piacenza, S.E.; Barner, A.K.; Benkwitt, C.E.; Boersma, K.S.; Cerny-Chipman, E.B.; Ingeman, K.E.; Kindinger, T.L.; Lee, J.D.; Lindsley, A.J.; Reimer, J.N.; et al. Patterns and variation in benthic biodiversity in a large marine ecosystem. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.D.; Phillips, I.R.; Hawker, D.W. Geochemical partitioning of copper, lead, and zinc in benthic, estuarine sediment profiles. J. Environ. Qual. 2005, 34, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.I.; Clark, D.; Atalah, J.; Jiang, W.; Taiapa, C.; Patterson, M.; Sinner, J.; Hewitt, J. Multiple stressor effects on marine infauna: Responses of estuarine taxa and functional traits to sedimentation, nutrient and metal loading. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, G.S. The biology of Aglaophamus neotenus (Polychaeta: Nephtyidae), a new species from Maine and Canada. Biol. Bull. 1980, 158, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocklington, P. Polychaetes of Eastern Canada: An Illustrated Key to Polychaetes of Eastern Canada Including the Eastern Arctic; Department of Fisheries and Oceans: Mont-Joli, QC, Canada, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.A.; Miller, J.E.; Calabrese, A. Effect of heavy metals on bay scallops, surf clams, and blue mussels in acute and long-term exposures. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1988, 17, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation, 2nd ed.; PRIMER-E Ltd.: Plymouth, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Séguin, A.; Gravel, D.; Archambault, P. Effect of disturbance regime on alpha and beta diversity of rock pools. Diversity 2014, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.M.; Curtis, M.; Hussin, W.; Froján, B.; Defew, E.C.; Nye, V.; Paterson, D.M. Implications of dredging induced changes in sediment particle size composition for the structure and function of marine benthic macrofaunal communities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2087–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, E.; Roberts, D. Contaminants reduce the richness and evenness of marine communities: A review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarelli, R.; Roccheri, M.C. Marine invertebrates as bioindicators of heavy metal pollution. Open J. Met. 2014, 4, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, M.; Usseglio-Polatera, P.; Archaimbault, V.; Larras, F.; Méthot, G.; Bernadette, P.-A. Assessing anthropogenic pressure in the St. Lawrence River using traits of benthic macroinvertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 649, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, C.T.; Smith, J.N.; Côté, R. The Saguenay Fiord: A major tributary to the St. Lawrence Estuary. In Oceanography of a Large-Scale Estuarine System; El-Sabh, M., Silverberg, N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 378–420. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, J.L.; Stehr, C.M.; Boyd, D.T.; Burrows, D.G.; Tkalin, A.V.; Lishavskaya, T.S. Organic and trace metal contaminants in sediments and English sole tissues from Vancouver Harbour, Canada. Mar. Environ. Res. 2004, 57, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourget, E. Les Animaux Littoraux du Saint-Laurent; Presses de l’Université Laval: Québec, QC, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelet, G. The choice of a sieving mesh size in the quantitative assessment of marine macrobenthos: A necessary compromise between aims and constraints. Mar. Environ. Res. 1990, 30, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Unit | 0.5 mm Size Class | 1 mm Size Class |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxa richness | taxa | 14.27 (0.53) | 7.58 (0.31) |

| Density of individuals | ind.grab−1 | 225.91 (32.94) | 39.62 (4.3) |

| Shannon diversity | NA | 1.79 (0.04) | 1.42 (0.05) |

| Pielou evenness | NA | 0.71 (0.01) | 0.75 (0.02) |

| Taxonomic distinctness | NA | 69.14 (0.5) | 76.49 (1.22) |

| Model 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Depth | OM/silt | Gravel | Sand | Clay | R 2adj | |

| 0.5 mm size class (n = 159) | |||||||

| Specific richness | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.24 (0.07) | 0.29 (0.08) | 0.2 (0.09) | 0.25 (0.12) | 0.75 (0.11) | 0.33 |

| p-value = | 0.7095 | 0.0011 | 0.0005 | 0.0267 | 0.0305 | <0.0001 | |

| Density of individuals | 0.02 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.07) | 0.54 (0.07) | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.11) | 0.89 (0.1) | 0.5 |

| p-value = | 0.7992 | 0.1524 | <0.0001 | 0.137 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Shannon diversity | 0.06 (0.06) | 0.54 (0.07) | — | 0.16 (0.09) | — | 0.29 (0.07) | 0.27 |

| p-value = | 0.3786 | <0.0001 | 0.0671 | <0.0001 | |||

| Pielou evenness | 0.05 (0.07) | 0.31 (0.08) | -0.14 (0.08) | — | −0.2 (0.12) | −0.22 (0.11) | 0.16 |

| p-value = | 0.4181 | <0.0001 | 0.0713 | 0.0825 | 0.0523 | ||

| 1 mm size class (n = 195) | |||||||

| Specific richness | −0.03 (0.06) | 0.27 (0.07) | — | — | −0.39 (0.08) | −0.46 (0.11) | 0.25 |

| p-value = | 0.5874 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Density of individuals | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.17 (0.08) | — | — | −0.2 (0.09) | −0.31 (0.13) | 0.03 |

| p-value = | 0.7931 | 0.0234 | 0.0272 | 0.0217 | |||

| Shannon diversity | −0.03 (0.06) | 0.43 (0.06) | — | -0.12 (0.08) | −0.31 (0.07) | −0.32 (0.11) | 0.34 |

| p-value = | 0.6265 | <0.0001 | 0.1292 | <0.0001 | 0.0029 | ||

| Pielou evenness | 0.02 (0.07) | 0.31 (0.07) | — | — | — | — | 0.1 |

| p-value = | 0.8276 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Model 2 | |||||||

| Intercept | As | Cd | Cr/Fe/Mn | Hg | Cu/Pb/Zn | R2adj | |

| 0.5 mm size class (n = 142) | |||||||

| Specific richness | −0.06 (0.08) | −0.41 (0.13) | −0.69 (0.15) | — | −0.46 (0.16) | 1.03 (0.19) | 0.18 |

| p-value = | 0.4276 | 0.003 | <0.0001 | 0.0051 | <0.0001 | ||

| Density of individuals | −0.11 (0.06) | −0.51 (0.1) | 0.74 (0.13) | 0.27 (0.11) | −0.73 (0.13) | 1.43 (0.16) | 0.49 |

| p-value = | 0.0641 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.013 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Shannon diversity | 0.04 (0.08) | — | — | −0.28 (0.08) | — | — | 0.07 |

| p-value = | 0.6124 | 0.0007 | |||||

| Pielou evenness | 0.06 (0.08) | — | — | −0.17 (0.08) | — | — | 0.02 |

| p-value = | 0.4713 | 0.0345 | |||||

| 1 mm size class (n = 126) | |||||||

| Specific richness | 0.06 (0.08) | — | −0.51 (0.15) | — | — | 0.31 (0.15) | 0.08 |

| p-value = | 0.4529 | 0.0009 | 0.0375 | ||||

| Density of individuals | 0.02 (0.09) | — | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| p-value = | 0.8373 | ||||||

| Shannon diversity | 0.09 (0.08) | — | −0.43 (0.15) | — | — | 0.29 (0.14) | 0.05 |

| p-value = | 0.2492 | 0.0038 | 0.0437 | ||||

| Pielou evenness | 0.06 (0.08) | — | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| p-value = | 0.4249 | ||||||

| 0.5 mm Size Class | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |

| A | 37.68 | ||

| B | 92.53 | 84.85 | |

| C | 90.37 | 91.67 | 69.35 |

| 1 mm Size Class | |||

| D | E | F | |

| D | 92.57 | ||

| E | 92.16 | 69.15 | |

| F | 94.82 | 97.87 | 75.43 |

| 0.5 mm Size Class | 1 mm Size Class | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unit | Cluster A | Cluster B | Cluster C | Cluster D | Cluster E | Cluster F |

| All four sectors | (n = 16) | (n = 61) | (n = 89) | (n = 83) | (n = 27) | (n = 89) | |

| Depth | m | 6.99 (0.35) | 13.72 (1.64) | 32.76 (2.02) | 21.5 (1.88) | 16.1 (2.53) | 32.52 (2.04) |

| Organic matter | % | 2.58 (0.42) | 0.52 (0.04) | 1.76 (0.1) | 0.72 (0.08) | 0.35 (0.03) | 1.77 (0.1) |

| Gravel | % | 0 (0) | 5.9 (1.8) | 1.7 (1) | 6.8 (1.6) | 2.2 (0.1) | 1.7 (1) |

| Sand | % | 0 (0) | 53.3 (5.3) | 46.3 (2.3) | 63.8 (3.7) | 92.4 (1.8) | 47 (2.5) |

| Silt | % | 0.1 (0) | 11.3 (2.4) | 49.1 (2.2) | 25 (3) | 4.7 (1.2) | 48.4 (2.5) |

| Clay | % | 99.9 (0) | 29.5 (5.6) | 3 (1.6) | 4.4 (1.2) | 0.6 (0.01) | 2.9 (1.5) |

| Baie des Sept Îles only | (n = 16) | (n = 47) | (n = 88) | (n = 42) | (n = 3) | (n = 89) | |

| Arsenic | mg·kg−1 | 3.74 (0.32) | 2.51 (0.19) | 3.89 (0.24) | 3.56 (0.55) | 1.83 (0.52) | 3.96 (0.25) |

| Cadmium | mg·kg-1 | 0.15 (0.01) | 0.11 (0.01) | 0.14 (0.01) | 0.13 (0.01) | 0.1 (0.01) | 0.14 (0.01) |

| Chromium | mg·kg−1 | 80.29 (5.34) | 54.5 (3.68) | 58.07 (1.71) | 51.77 (3.5) | 32.73 (5.27) | 58.19 (1.66) |

| Copper | mg·kg−1 | 19.89 (1.33) | 6.86 (0.73) | 12.33 (0.51) | 9.3 (1.05) | 6.37 (1.39) | 12.26 (0.5) |

| Iron | g·kg−1 | 64.73 (3.73) | 57.56 (4.42) | 55.27 (1.68) | 49.2 (2.47) | 33.56 (4.57) | 54.96 (1.69) |

| Manganese | g·kg−1 | 2.17 (0.32) | 0.93 (0.06) | 1.18 (0.06) | 0.86 (0.06) | 0.57 (0.09) | 1.17 (62.25) |

| Mercury | mg·kg−1 | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) |

| Lead | mg·kg−1 | 7.32 (0.58) | 3.26 (0.27) | 5.46 (0.2) | 4.65 (0.4) | 2.63 (0.37) | 5.59 (0.2) |

| Zinc | mg·kg−1 | 77.21 (4.22) | 43.54 (2.25) | 61.09 (1.77) | 54.28 (4.09) | 39.77 (3.11) | 61.61 (1.68) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dreujou, E.; McKindsey, C.W.; Grant, C.; Tréau de Coeli, L.; St-Louis, R.; Archambault, P. Biodiversity and Habitat Assessment of Coastal Benthic Communities in a Sub-Arctic Industrial Harbor Area. Water 2020, 12, 2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12092424

Dreujou E, McKindsey CW, Grant C, Tréau de Coeli L, St-Louis R, Archambault P. Biodiversity and Habitat Assessment of Coastal Benthic Communities in a Sub-Arctic Industrial Harbor Area. Water. 2020; 12(9):2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12092424

Chicago/Turabian StyleDreujou, Elliot, Christopher W McKindsey, Cindy Grant, Lisa Tréau de Coeli, Richard St-Louis, and Philippe Archambault. 2020. "Biodiversity and Habitat Assessment of Coastal Benthic Communities in a Sub-Arctic Industrial Harbor Area" Water 12, no. 9: 2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12092424

APA StyleDreujou, E., McKindsey, C. W., Grant, C., Tréau de Coeli, L., St-Louis, R., & Archambault, P. (2020). Biodiversity and Habitat Assessment of Coastal Benthic Communities in a Sub-Arctic Industrial Harbor Area. Water, 12(9), 2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12092424