Abstract

As water scarcity becomes of greater concern in arid and semi-arid regions due to altered weather patterns, greater and more accurate knowledge regarding evapotranspiration of crops produced in these areas is of increased significance to better manage limited water resources. This study aimed at determining the actual evapotranspiration (ETa) and crop coefficients (Ka) in California date palms. The residual of energy balance method using a combination of surface renewal and eddy covariance techniques was applied to measure ETa in six commercial mature date palm orchards (8–22 years old) over one year. The experimental orchards represent various soil types and conditions, irrigation management practices, canopy characteristics, and the most common date cultivars in the region. The results demonstrated considerable variability in date palm consumptive water use, both spatially and temporally. The cumulative ETa (CETa) across the six sites ranged from 1299 to 1501 mm with a mean daily ETa of 7.2 mm day−1 in June–July and 1.0 mm day−1 in December at the site with the highest crop water consumption. The mean monthly Ka values varied between 0.63 (December) and 0.90 (June) in the non-salt-affected, sandy loam soil date palms with an average density of 120 plants ha−1 and an average canopy cover and tree height of more than 80% and 11.0 m, respectively. However, the values ranged from 0.62 to 0.75 in a silty clay loam saline-sodic date palm orchard with 55% canopy cover, density of 148 plants ha−1, and 7.3 m tree height. Inverse relationships were derived between the CETa and soil salinity (ECe) in the crop root zone; and between the mean annual Ka and ECe. This information addresses the immediate needs of date growers for irrigation management in the region and enables them to more efficiently utilize water and to achieve full economic gains in a sustainable manner, especially as water resources become less available or more expensive.

1. Introduction

Dates (Phoenix dactylifera L.) are one of the world’s oldest cultivated fruits [1]. Originating in the Middle East, its distribution extended to the United States in the last century. The geographical distribution of commercial date production is limited to arid and semi-arid regions where there is abundant water supply. The low desert of California with a planted area of nearly 4500 hectares of date palms [2] is the major date production area within the United States followed by Arizona. Since the date industry is currently economically successful and robust in California, date production is expected to increase as many new groves were planted in recent years and are currently being planted. Accurate information on crop water use along with irrigation best management practices are immediate needs of date palm growers, specifically when the region is facing increasing uncertainty concerning water supplies and efficient use of irrigation water is the highest conservation priority.

The best date palm growing regions are characterized by long, hot, dry summers with minimal summer–fall rainfall since a long, hot, and arid growing season is required for date palm growth and the development of ripe fruits. Early maturing varieties such as ‘Medjool’ and ‘Deglet Noor’ in the low desert region, require about 6500 degree-days of heat units from flowering (February–March) to fruit ripening (September–November) [3]. The date palm is believed to be a relatively high water-use crop where substantial water resources are needed for date production in highly productive areas. For instance, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with over 40 million date palm trees, has the largest number of date palms in the world [4], and there are more than 23 million date palms reported in Saudi Arabia [5]. In the UAE, irrigation water of date palm accounts for about one third of the country’s groundwater resources, and hence, there are serious water quantity challenges and emerging problems associated with the increasing salinity of the remaining groundwater resources [6].

Despite the date palm’s regional and international importance and its dependence on irrigation or a shallow water table for survival, relatively little research on irrigation requirements and management has been published. Date palm growers have started to adopt the use of microirrigation, but, in many instances, irrigation management is based upon data developed decades ago in flood (basin) irrigated orchards. Both micro/drip and flood irrigation are common practices in the low desert region of California, and some growers, who have installed microirrigation systems in their groves, prefer to irrigate their date palms through an integrated micro-flood irrigation system.

Various methods of evapotranspiration measurement have been discussed by several researchers [7,8,9,10]. The most common methods for evapotranspiration (ET) measurement may be categorized as hydrological approaches (soil water balances and lysimeter measurements), micrometeorological approaches (eddy covariance, surface renewal, and Bowen ratio energy balances), and plant physiology approaches (chamber systems and sap flow measurements). In recent decades, satellite-based ET estimates using vegetation indices and scintillometer systems were developed as a result of rapid advances in instrumentation, data acquisition, and remote data access.

The early work in the United States on the water requirements of date palm was conducted near Indio, California by Furr and Armstrong in 1956 [11] using gravimetric soil sampling to estimate the annual water use of flood irrigated date palms. They reported annual irrigation water needs of 1300–1600 mm. Since this early work in the United States, only a few researchers have studied date palm water use using different techniques. For instance, Kassem [12] monitored the water use of date palm over a season on a commercial farm in Saudi Arabia using both the Bowen ratio energy balance method and a soil water-balance approach. An average annual actual crop water use of 1710 mm was calculated for drip-irrigated 15-year-old date palms. The corresponding crop coefficients (Kc) were 0.63 for February and 0.70 for July. Using a simple water-balance approach, the actual evapotranspiration was estimated to be 1800 mm per season for an 11-year-old palm in Jordan [13]. The seasonal Kc values were 0.75 for the winter, 1.00 for the spring, and 1.10 for the summer.

In Tunisia, the sap flow method (recalibrated Granier’s TDP-method) was used to monitor transpiration rate in four individual date palms [14]. The average transpiration rates ranged from about 0.5 mm day−1 in the winter (daytime temperature range of 9.0–19.0 °C) to 3.5 mm day−1 in the summer (daytime temperature range of 24.0–42.0 °C). The crop coefficient values varied from 0.60 to 0.70 in winter to 1.18 in summer. A daily annual mean ETc (crop water requirements) of 140 L day−1 was found for ‘Lulu’ date-palm tree in a study in the UAE [15]. The area covered by each tree was 64 m2. The measurements were conducted using the compensation heat-pulse method on six ‘Lulu’ date trees, a salt-tolerant date variety, at the International Center for Biosaline Agriculture.

An earlier experiment on date palm water management in the Riyadh, Saudi Arabia area indicated that the average amount of date palm water consumption per year was 2396 mm [5]. According to FAO [16], the crop water requirement for mature date palms varies from 1150 to 3060 mm depending upon the orchard conditions and the annual potential evapotranspiration. In another study, estimations of water requirements ranged between 300 and 700 L day−1 for a mature date palm during the peak demand period [17]. Different factors were considered for this estimation including localized evapotranspiration rates, precipitations, soil types, leaching requirements, and water quality.

The surface renewal (SR) and eddy covariance (ECov) techniques are classified as the residual energy balance (REB) method to measure the sensible heat flux density (H) and to calculate the latent heat flux density (LE) using the measurements of net radiation (Rn) and ground heat flux density (G) [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. The ECov method uses a sonic anemometer to measure sensible heat flux (H) and the SR method uses a fine-wire thermocouple to measure an uncalibrated sensible heat flux (H0) to estimate H. The ECov method is more widely accepted, but the SR method has the advantage that the least expensive sonic anemometer is more than 300 times more expensive than a thermocouple [25]. The ECov method involves simultaneous high-frequency measurements of vertical air velocity and scalar concentration, followed by computation of their covariance, which represents the vertical flux of the measured scalar. The ECov technique’s applicability at the farm level is limited, mainly because of the high cost of the sensors, complexity of their operation, and the intensive data analysis. The fetch requirement for SR is much less than for ECov.

To calibrate the SR method, the least squares regression of the ECov H versus the uncalibrated SR H0 data is computed and the slope of the regression through the origin provides a calibration where the product of H0 and the calibration factor provides an estimate of H. The calibration is computed separately for positive and negative H0 values to adjust for differences due to stable and unstable atmospheric conditions. Surface renewal H is calculated from the average heating of the air parcel and the number of times the air parcel is renewed at the surface over 30-min intervals as follows:

where α is a calibration factor, z is the measurement height, is the air density (g m−3), Cp is the specific heat of air at constant pressure (J g−1 K−1), and a is the average ramp amplitude (K), which corresponds to the temperature enhancement of the air parcel. The tr is the mean air parcel renewal time over the sampling period [27].

The ramp amplitude (a) and duration (tr) are determined using the Van Atta ramp model [28], which uses half-hour means of the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th moments of the air temperature structure function (Equation (2)).

where m is the number of data points in the half-hour interval measured at frequency (f), n is the order of the structure function, j is a sample lag between data points corresponding to a time lag (r = j/f), and Ti is the ith temperature sample (K). The 2nd, 3rd, and 5th moments are calculated and recorded for both r = 0.25 s and r = 0.50 s. Uncalibrated H values (H0) are calculated separately for each time lag from the mean ramp amplitude and mean ramp period (Equation (1)).

Since ECov is based on eddy covariance and SR is based on energy conservation, the two methods are independent, and good agreement implies a good estimate for H. The advantage from using SR is that the fetch requirement is less since it is possible to mount the thermocouple sensor closer to a canopy than the sonic anemometer. The residual of the energy balance method, like the Bowen Ratio, assumes closure of the energy balance and uses Equation (3):

where LE, G, and H are positive away from the surface and Rn is positive towards the surface. The G is the ground heat flux density at the soil surface. It assumes that Rn, G, and H are measured accurately. While use of the full eddy covariance method often does not demonstrate closure, Twine et al. [29] recommended that H and LE ECov raw fluxes can be forced to have closure by holding the measured Bowen ratio (H/LE) constant and increasing the H and LE values until Rn − G = H + LE. Twine et al. [29] also reported that using the REB method gave nearly the same accuracy as using the Bowen ratio correction. Recent research has shown that self-calibration of the SR method is possible if corrections are made for the wire diameter [30].

LE = Rn − G − H

The data available on crop water consumption of the date palm varies considerably from one country to another and even within an individual country, mainly as a result of differences in climate, canopy characteristics, soil types and conditions, and management practices. In addition, many of the studies were reported before the adoption of the standardized reference evapotranspiration (ETo) equation for short canopies [7,31,32], and therefore the crop coefficient reports prior to 1998 are possibly out-of-date.

The objective of this study is to acquire crop water use and crop coefficient information for California date palm production systems. Its aims are to better understand the impacts of environmental and plant factors on crop water use and to conduct a preliminary assessment on monthly date palm crop coefficient values. The novelty of the attempt is using the REB method with a combination of surface renewal and eddy covariance techniques, which its application to date palms had not been conducted previously. This original combination allows a more robust determination of the latent heat flux than the direct measurement using ECov and fast response hygrometers. While there is only scarce information on the water use of date orchards, this study intends to develop a data set and relationships that could serve as a reference for further studies and applications to date production in arid and semi-arid regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Orchards

Six mature commercial date palm orchards in the Coachella and Imperial Valleys, California (designated “DP1” through “DP6”) were chosen and instrumentation installed in March 2019. The experimental orchards represent various soil types and conditions, irrigation management practices, canopy features, and the most common date cultivars in the California low desert region. The irrigation practices consisted of flood irrigation, drip/microsprinkler, and integrated drip and flood irrigation (Table 1). The irrigation system has dual driplines at sites DP3 and DP5 and a single dripline at sites DP1 and DP2. During summer, the irrigation systems are typically running six days a week for about 8–10 h a day with a nominal emitter’s flow rate of 3.8 L h−1.

Table 1.

General information for date palm sites 1–6 (DP1, DP2, DP3, DP4, DP5, and DP6).

The experimental orchards were 8–22 years old. Sites DP1 and DP6 were planted with the ‘Medjool’ cultivar and sites DP2 through DP5 were planted with the ‘Deglet Noor’ cultivar. Soil characteristics referring to four generic horizons are provided in Table 2. The orchards have a relatively heterogeneous soil; however, the dominant soil texture varies from sandy loam at sites DP1, DP2, DP3, and DP4 to silty loam and silty-clay loam at sites DP5 and DP6. Soil cation exchange capacity (CEC) ranged between 6.6 and 13.9 meq/100 g at DP2 to between 26.1 and 35.8 meq/100 g at DP5. The Colorado River was the source of irrigation water with a pH of 8.1 and an electrical conductivity (EC) of 1.1 dS m−1 for all orchards. The irrigation water is classified as water with medium salinity and sodium hazards. Groundwater data are limited for the study area because of the poor quality in the upper 100 m. Since the groundwater table is deep enough, insignificant contribution is expected from groundwater resources.

Table 2.

Physical and chemical properties of the soils of the experimental sites. CEC represents the cation exchange capacity (meq/100 g). DP1, DP2, DP3, DP4, DP5, and DP6 represent date palm sites 1 through 6.

The quantitative data of soil evaporation is not available for the experimental orchards. Theses date palms are organic orchards. The sources of organic matter are pruning, animal manure, and compost. Prunings are dropped under trees, disk, and buried in the soil to speed up decomposition. Applying manure and composts in the late fall to winter, and multiple tillage operations the entire season are common soil management practices in the date palm orchards. Soils high in clay and silt (particularly orchards DP5 and DP6) swell and shrink as their moisture content fluctuates from wet to dry. Shrinking results in moderate to severe cracking, and cracks often extend down several centimeters. A higher soil surface evaporation is expected in orchards DP5 and DP6 when compared with orchards DP1–DP4.

2.2. Monitoring Stations and Data Processing

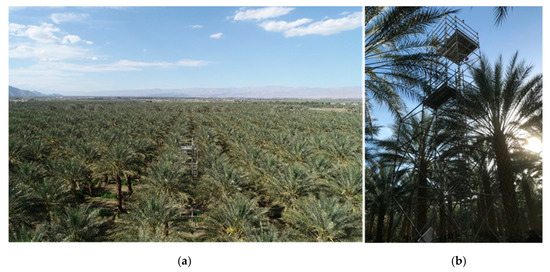

In this study, a combination of two methods of energy balance calculations (ECov and SR techniques) was applied to measure date palm actual ET (ETa). A flux density measurement tower was set up in each of the experimental date palm sites (Figure 1). The towers were placed in the orchard rows midway between two trees. Two different types of flux tower, i.e., full-flux and lite-flux were used in this study. Sites DP1, DP3, and DP6 were equipped with the full-flux tower and sites DP2, DP4, and DP5 were equipped with the lite-flux tower.

Figure 1.

(a) Flux tower set up at the DP3 experimental site located in Thermal, California, and (b) an aerial view of the tower from a distance and the right picture demonstrates a ground view of the tower.

The full-flux tower consisted of (1) a sonic anemometer (RM Young Inc. model 81000RE, Traverse City, MI, USA) to collect high frequency wind velocities in three orthogonal directions at 10 Hz for estimating H using the eddy covariance technique; (2) two 76.2 μm diameter, type-E, chromel-constantan thermocouples model FW3 (Campbell Scientific Inc., Logan, UT, USA) to measure high frequency temperature data for computing uncalibrated sensible heat flux (H0) using the surface renewal technique; (3) a NR LITE 2 net radiometer (Kipp and Zonen Ltd., Delft, The Netherlands) to measure net radiation; (4) three HFT3 heat flux plates (Radiation and Energy Balance Systems (REBS) Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) inserted at 0.05 m depth below the soil surface to measure soil heat storage at three different locations; (5) three 107 thermistor probes (Campbell Scientific Inc.) to measure soil temperature at three depths in the soil layer above the heat flux plates; (6) three EC5 soil moisture sensors (METER Groups, Inc., Pullman, WA, USA) to measure soil volumetric water content at the depths and locations near the heat flux plate and thermistor probes; (7) EE181 temperature and RH sensor (Campbell Scientific Inc.) to measure air temperature and relative humidity; (8) an SP LITE 2 Pyranometer (Kipp and Zonen Ltd.) to measure solar radiation; (9) a TE525MM tipping-bucket rain gauge with magnetic reed switch to measure precipitation; and (10) two SI-411fixed view-angle infrared thermometers (IRTs, Apogee Instruments, Logan, UT, USA) to measure canopy temperature.

One of the G packages was located in the tree row (where the ET tower was set up) next to the tree trunk where the surrounding soil was wetted when the drip system operated. The second G package was located at 1/3 of the distance between the row and the first G package, while the third G package was located at 2/3 of the distance to the next row. The ground heat flux at the soil surface was estimated using a continuity equation as described by De Vries [33] using the mean HFT3 heat flux plate measurements, the temperature changes in the depths measured by 107 thermistor probes, and the volumetric water content.

To avoid shading/reflections and to promote spatial averaging, the net radiometers were set up about 1.2–1.3 m above the maximum height of date trees and away from all obstructions or reflective surfaces that might adversely affect the measurement. The net radiometers were mounted at the edge of the scaffold structures to obtain a good integrated view of the canopy and orchard floor. Except for the soil sensors, all other sensors were set up 0.8 m above the tree canopy on the top of the flux towers. The two IRTs were installed on opposite sides of flux tower and were angled below the horizon to ensure sensing primarily the canopy of the two trees adjacent to the tower. The data were recorded using a combination of a Campbell Scientific CR1000X data logger and a CDM-A116 analog input module. Direct two-way communication with each monitoring station was possible using a cellular phone modem model CELL210 (Campbell Scientific Inc.). The data of the sonic anemometer and fine wire thermocouples were collected at a 10 Hz sampling rate and the data of the other sensors were sampled once per minute. Half-hourly data were archived for later analysis.

The residual of energy balance method was used (Equation (3)) to calculate the latent heat flux density. The available energy components, Rn and G, were measured, and the ECov and SR techniques were employed to determine H values. For the SR calculations, a time lag of 0.5 s was considered to calculate uncalibrated half-hourly SR sensible heat flux density (H0) using a modified version of the van Atta [28] structure function. The modified version was defined by Shapland et al. [30]. After acquiring the half-hourly H0 data, a calibration factor (α) was established by determining the slope through the origin H values from the ECov technique versus H0 from the SR technique separately for positive and negative values of H0. The calibrated SR H value was finally estimated as H = α∙H0. The ECov H was preferentially used over the SR H0, but α∙H0 was used when the ECov data were missing. The advantage from using both the ECov and SR methods is that they are independent and similar results provide a high level of confidence in the data used [25,34].

The daily LE was derived as the sum of the 48 half-hourly LE calculations over a 24-h day. Daily LE (MJ m−2 day−1) was converted to daily actual ET, ETa (mm day−1) using Equation (4):

ETa = LE/2.45

In which 2.45 MJ kg−1 is the approximate energy needed to vaporize 1.0 mm depth of water from a 1.0 m2 surface area within the surface temperature range commonly observed in this project.

The lite-flux towers consisted of two 76.2 μm diameter chromel-constantan thermocouples model FW3 (Campbell Scientific Inc.), a NR LITE 2 net radiometer (Kipp and Zonen Ltd.), and two SI-411fixed view-angle infrared thermometers (Apogee Instruments). The infrared thermometers had a bandpass filter in the thermal portion (8–14 µm) of the electromagnetic spectrum, the accuracy of this sensor was ±0.2 °C over a temperature range of −10–65 °C, and an average output sensitivity of 55.178 µV/°C. In each of the lite stations, a RM Young sonic anemometer (model 81000RE) was used for a 40-day period to estimate ECov and H and develop the SR calibration factor (α). The daily LE was obtained by summing the 48 half-hourly LE calculations over a 24-h day as LE = Rn − α∙Ho. A daily total ground heat flux of 0 was assumed for the LE calculations. Even though the half-hourly LE for the lite stations is not strictly correct because of this assumption, the daily LE provides a good estimation for daily latent heat flux.

In both full and lite-flux stations, a combination of Watermark Granular Matrix Sensors (Irrometer Company Inc., Riverside, CA, USA) was used to measure soil water tension and TEROS 12 sensors (METER Groups Inc.) to measure soil volumetric water content (VWC). They were installed at depths of 0.15, 0.30, 0.45, 0.60, 0.90, and 1.20 m to monitor both soil water tension and soil water content on a continuous basis. The data of the TEROS 12 and Watermark sensors were recorded by a ZL6 cellular data logger and 900M Monitor on a 30-min basis, respectively. The location of soil moisture sensors relative to the date palm root system and drip emitters influence the usefulness of the sensor readings. If sensors are placed too far from active roots, the effect of water movement in the mass flow cannot be captured. Likewise, placement too far from the emitter can lead to excess watering of the date tree if the sensor is not within the desired wetting pattern of a routine irrigation set. To avoid over watering, the sensors were placed 10–15 cm from the emitter. The soil moisture sensors were positioned within 60–70 cm of date trunk and in line with driplines.

Using the daily ETa determined in each of the experimental sites and the daily reference ET (ETo) retrieved from the spatial CIMIS (California Irrigation Management Information System) data [35] for the coordinates of the monitoring station, the daily actual crop coefficient (Ka = Ks × Kc) was calculated for each site (Ka = ETa/ETo). To obtain the actual crop ET, a daily stress coefficient (Ks) representing water and salt stresses, management, and environmental multipliers is needed to adjust the crop coefficient (Kc). Spatial CIMIS combines remotely sensed satellite data with traditional CIMIS stations data to produce site specific ETo on a 2-km grid, which provides a better estimate of ETo for the individual sites. CIMIS uses the Penman–Monteith equation and a version of Penman’s equation modified by Pruitt and Doorenbos [36]. The modified Penman employs a wind function developed at UC Davis and is therefore referred to as the CIMIS Penman equation in different literatures. CIMIS uses hourly weather data to calculate hourly ETo and adds them up over 24 h (midnight to midnight) to estimate daily ETo.

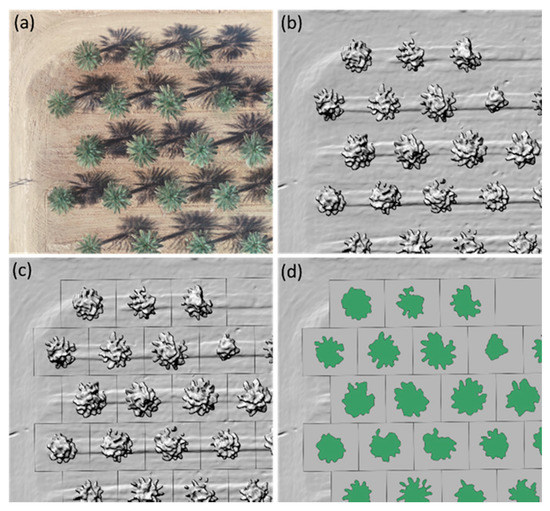

2.3. High Resolution Aerial Imagery Data Acquisition

Aerial image acquisition and processing was conducted by the Digital Agriculture laboratory at UC Davis. Oblique aerial RGB imagery was acquired using a small unmanned aerial system (sUAS; Phantom 4 PRO, DJI, Shenzhen, China) that includes a built-in full frame RGB camera with 20 megapixels resolution (effective pixels). The flight was conducted at 75 m altitude above ground in a double grid pattern with 82%, and 85% side, and front overlaps. The average ground sampling distance (imagery spatial resolution) was 1.86 cm. A third-party software (Pix4D Mapper, Lausanne, Switzerland) was used to process aerial imagery and generate orthomosaic (Figure 2a) and densified 3D point cloud reconstruction of date palm orchards using a photogrammetry technique [37]. A digital surface model (DSM, that is a 2.5D image in which each pixel represents the altitude of the corresponding point on the ground; Figure 2b) was extracted from point cloud data using Pix4D mapper software for each site. Individual palm trees were localized in the DSM and pixels belonging to trees were segmented from the ground pixel using a 0.5 m altitude threshold (that considered all pixels with altitude more than 0.5 m from the ground level as tree pixels). Individual tree height was calculated by averaging the tree pixel values in the DSM. Canopy cover feature was defined as the percentage of the allocated area for each tree (a rectangle with dimension tree spacing and row spacing, Figure 2c) that is occupied by tree canopy segmented from the ground (Figure 2d). Canopy cover provides a good estimation of canopy size and the amount of light that it can intercept [38]. More information about the virtual orchard approach can be found in https://digitalag.ucdavis.edu/research/virtual-orchard.

Figure 2.

Aerial image processing steps include (a) aerial orthomosaic RGB; (b) digital surface model (DSM); (c) allocated area for each tree; and (d) canopy segmented from the ground.

2.4. Soil Salinity Assessment

Soil properties were surveyed and characterized within an approximate footprint area of 200 m × 200 m around the flux monitoring towers. Surveys of apparent soil electrical conductivity (ECa) were conducted in April through June 2019 using mobile electromagnetic induction (EMI) equipment following guidelines developed by the U.S. Salinity Laboratory of the United States Department of Agriculture for field-scale salinity assessment [39,40,41,42]. Measurements of ECa were taken with a dual-dipole EM38 sensor (Geonics Ltd., Mississauga, ON, Canada), in the horizontal (EMh) and vertical (EMv) dipole modes to provide shallow (0–0.75 m) and deep (0–1.5 m) measurements of ECa, respectively. The measurements were taken both on the center of the bed in-line with the tree trunks (L0), and along the driplines (L1). At the sites where flood irrigation was the only irrigation system used, the measurements were taken both on the center of the bed in-line with the tree trunks (L0), and at the outer branch line, parallel to the tree trunk row lines, approximately 0.9 m away from the “L0” cores (L1). At each site, soil cores at four distinct depth ranges (0–0.3, 0.3–0.6, 0.6–0.9, and 0.9–1.2 m) were taken from 12 sampling locations (each location includes Lo and L1). A comprehensive laboratory analysis was conducted on the soil samples.

3. Results

3.1. Meteorological Variables

While there are currently five CIMIS weather stations in the study area, Oasis # 136 CIMIS station was used as the representative weather station. The station is in the Imperial/Coachella Valley Region at elevation 3.6 m above sea level, latitude 33°31′25″ N, and longitude 116°9′21″ W. The study area has a true desert climate with an annual mean air temperature, total annual precipitation, and ETo of 23.1 °C, 52 mm, and 1799 mm, respectively (Table 3). The 12-month period of this study was warmer than usual with a wetter late-winter/early-spring period than normal. The annual mean air temperature, total annual precipitation, and ETo showed increases during the study period when compared with the long-term monthly data. For instance, the annual average air temperature was 24.1 °C and annual rainfall was 127.0 mm during the study period, which were 4% and 245% higher than the long-term means, respectively. The annual average solar radiation was approximately increased by 5%, and there was a 2% increase in the annual mean wind speed.

Table 3.

Monthly mean long-term climate data versus monthly data of the study period for Oasis # 136 California Irrigation Management Information System (CIMIS) station. The mean monthly data of a 10-year period (2009–2018) is reported as long-term climate data, and the monthly data of May 2019 through April 2020 is reported as this study period.

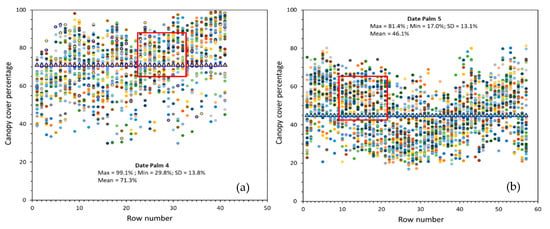

3.2. Orchard Canopy Features

At the experimental sites, canopy vegetation cover percentage for each tree derived from drone-based multispectral imagery ranged from 0 (missing trees) to 100% across. Results for the trees at sites DP4 and DP5 are shown in Figure 3. There were 41 rows and 41 columns with tree spacings of 9.1 m × 9.1 m at site DP4 site, and 58 rows and 51 columns with tree spacings of 8.2 m × 8.2 m at site DP5. Both orchards are surrounded by neighboring date palm plantings of approximately the same age. The canopy cover varied from 32.2% to 98.9% at site DP4 versus from 18.1% to 79.3% at site DP5. High variability of canopy cover percentage was observed at both sites, while the mean values were considerably different. The mean canopy cover was determined to be 71.3% (SD = 13.8%) at site DP4 and 46.2% (SD = 13.1%) at site DP5. The mean canopy cover around the monitoring tower (100 m × 100 m, the station was in the center of this area) was 81.4% and 54.7% at sites DP4 and DP5, respectively. It was assumed that the canopy characteristics around the monitoring stations have the most influence on the measured ETa.

Figure 3.

Canopy cover percentage of each living tree at the (a) DP4 and (b) DP5 sites. There were 41 rows and 41 columns at the DP4 site, and 58 rows and 51 columns at the DP5 site. The red box shows the corresponding canopy cover trees located in a 100 m × 100 m area around the monitoring flux towers. The canopy cover percentage of trees can be read using the row numbers, while dots (trees) with the same colors belong to the same row.

The results indicate that site DP4 has taller trees when compared with site DP5 (Table 4). The mean tree height was estimated 9.2 m (SD = 1.7 m) for the entire orchard and 11.5 m (SD = 0.65 m) around the tower at site DP4. The mean tree height was estimated 5.3 m (SD = 1.4 m) for the entire and 7.3 m (SD = 0.58 m) around the tower at site DP5.

Table 4.

Statistical indicators of trees height (m) at sites DP4 and DP5. The living trees in each of these date palms were considered in the calculations. The number of trees is given in parentheses. SD represents standard deviation.

Sites DP1 and DP2 were close to the airport and the drone flights were conducted at low altitude to prevent interference with the airport operations. As a result, the aerial images were not good enough to produce an accurate densified point cloud and, hence, a good measure of canopy cover in those orchards. Based on the field observations, sites DP2 and DP3 had similar canopy features as site DP4.

While the orchard leaf surface area was not measured in this study, there is an earlier study conducted in the Coachella Valley reported that an average mature date tree in the region has approximately 150–250 leaves of all sizes [3]. Each leaf has a surface area of about one square meter. Therefore, the total leaf area is about 150–250 m2 per date tree.

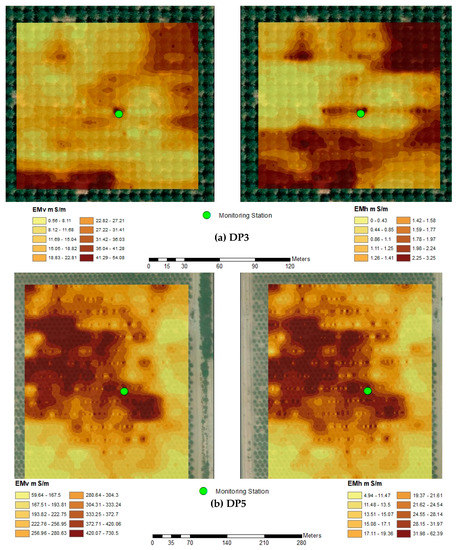

3.3. Soil Salinity Conditions

Soil salinity parameters varied considerably between the experimental site DP5 and the other five sites. Figure 4 illustrates spatially interpolated maps of ECa (EMh and EMv) at sites DP3 and DP5. Low measurements (EMh < 0.54 mS m−1 and EMv < 0.03 dS m−1) defined the entire survey area around the monitoring station at site DP3. Most of the surveyed area at site DP5 exhibited moderate-to large (2.0–4.0 dS m−1), large (4.0 to 6.0 dS m−1), or extremely large (>6.0 dS m−1) EMh measurements. Small EMv measurements (<1.0 dS m−1) were recorded at this site. High soil salinity at site DP5 resulting from poor drainage and the orchard’s location was a major cause of the high EMh measurements. This orchard is located about 2500 m southwest of the Salton Sea, which is a large shallow saline lake located directly on the San Andreas Fault, predominantly in California’s Imperial and Coachella valleys. Inflows from the Alamo and New Rivers comprise of over 80% of the inputs to the Salton Sea. Much of these inflows are comprised of agricultural runoff and drainage water originally derived from the Imperial Valley, which have high levels of salts and other ions from agricultural chemicals [43].

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of ancillary variables EMh (electromagnetic induction measurement in the horizontal coil orientation) and EMv (electromagnetic induction measurement in the vertical coil orientation) at the (a) DP3 and (b) DP5 experimental sites. 100 m S m−1 is equal 1 dS m−1.

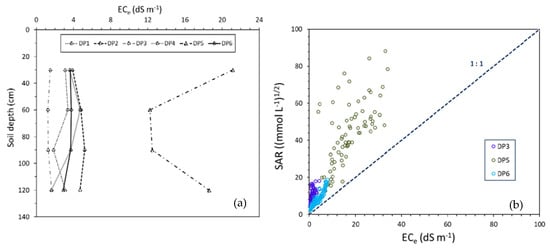

The mean ECe at the experimental sites demonstrates that while the entire soil profile was saline at site DP5 (ECe > 12.0 dS m−1), ECe was more than 20.0 dS m−1 in the topsoil and in the lower subsoil (Figure 5a). Relatively low values of ECe (<5.0 dS m−1) were observed within the crop root zone at the other experimental sites. Extremely large SAR at site DP5 (mean = 44.7 (mmol L−1)1/2, maximum = 88.2 (mmol L−1)1/2, minimum = 13.0 (mmol L−1)1/2, and standard deviation = 17.1 (mmol L−1)1/2) indicates that the orchard is highly sodic as well (Figure 5b). The particle size distribution at site DP5 has a larger clay content below the topsoil than any other site, which along with a high content of soluble salts and high soluble Na resulted in both water penetration and subsurface drainage problems.

Figure 5.

Whole-soil profile representations of (a) mean ECe (electrical conductivity of the saturation extract) distribution of observed values at six experimental date palm sites and (b) soil SAR (sodium adsorption ration) versus ECe at the DP3, DP5, and DP6 sites. The complete data from the 24 soil core sampling locations were used to plot SAR vs. ECe. The salinity surveys were conducted in April through June 2019.

3.4. Energy Flux Density Analysis

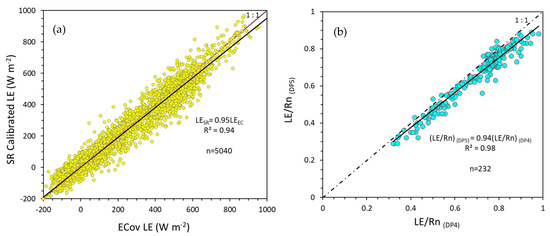

The SR calibration factors were determined separately for the positive and negative half-hourly sensible heat flux values using the ECov H values for each site. Using the half-hourly ECov H and SR H0, LE was calculated from the REB approach, employing the same Rn and G values. The REB estimates of half-hourly LE computed from ECov and SR techniques had a good agreement, for instance, a linear relationship LESR = 0.95∙LEECov with a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.94 was found at site DP3 (Figure 6). The reliability of the SR analysis in LE estimates has been also confirmed for pistachio [44], paddy rice [25], urban landscape [34], wine grapes [45], and wheat [46].

Figure 6.

(a) Half-hourly eddy covariance (ECov) latent heat flux density (LE) versus calibrated surface renewal (SR) LE from a 104-day period at the DP3 experimental site. The LE values were computed using the residual energy balance (REB) method and calculated with either SR sensible heat flux density (H) or ECov H; (b) the ratio of half-hourly LE to half-hourly Rn at site DP6 versus site DP4. Daily time values of a 10-day period (14 June through 23 June 2019) from each site were used for this analysis.

To evaluate the validity of Rn raw data, the ratio of half-hourly LE to half-hourly Rn at site DP5 was compared with the corresponding LE/Rn values at site DP4 over a 10-day period. The LE/Rn values were lower at site DP5 where has a lower canopy cover (average of 54.7% around the monitoring tower) than site DP4 with an average canopy cover of 81.4% around the monitoring tower. Consequently, the Rn measurements were accurate enough for the ETa estimates.

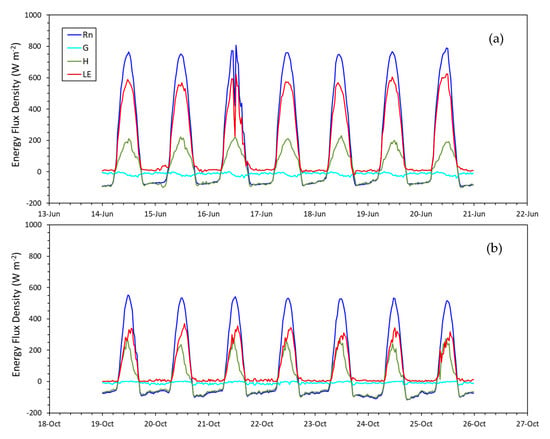

Half-hourly energy flux densities are shown for two different 7-day periods of the year in June (12:00 a.m. on 14 June though 11:30 p.m. on 20 June) and October (12:00 a.m. 19 October through 11:30 p.m. 25 October) at site DP3 (Figure 7). The flux densities of Rn, H, and LE showed a wide range of variations over time (hours of day, daily, and month). While an average daily maximum net radiation of 770 W m−2 was observed in June (during the 7-day period), this value decreased to 534 W m−2 in October. Generally, higher net radiation energy flux was observed in June when global radiation energy was higher (a maximum solar radiation value of 1040 W m−2 was recorded at 12:30 p.m. on 16 June). The average daily maximum LE over the 7-day period in June was 593 W m−2, which reduced to 340 W m−2 in October. The results illustrate that there was not much difference between the soil heat flux values in June and October. In this date palm, the soil surface is under non-deciduous large vegetation cover of date palms that plays the entire season as the role of a blanket for heat exchanges between the soil and the atmosphere. Therefore, the magnitude of the soil heat balance remains relatively the same all along the year. This result is expected to be different for a bare soil or under deciduous trees. More variations were observed in the G values of the site DP1 and DP6 where canopy cover is quite less than site DP3. The results also demonstrate similar H values during June and October showing a larger partitioning of the available energy to sensible rather than latent heat flux in October. Therefore, the elevated latent heat flux in June is mainly due to higher net radiation.

Figure 7.

Half-hourly net radiation (Rn), sensible heat flux density (H), ground heat flux density (G), and latent heat flux density (LE) in a period of 7 days on (a) 14 June through 20 June 2019; and (b) 19 October through 25 October 2019 at the DP3 experimental site.

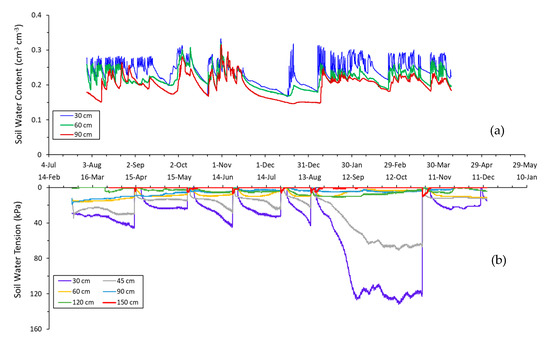

3.5. Soil Moisture and Canopy Temperature Interpretation

Half-hourly soil VWC and soil water tension were recorded at multiple depths in each of the monitoring stations. The results of several-month measurements were plotted for sites DP3 and DP6 in Figure 8. Soil VWC remained high at site DP3 during the summer and the winter–spring reflecting frequent drip irrigation events and three flood irrigation events (Figure 8a). During the fall, irrigation was not as frequent as in other seasons. One flood irrigation event took place on 8 November. At site DP6, six flood irrigation events occurred from mid-April 2019 to late-October 2019 along with 25 mm of rainfall on 9 December (Figure 8b). Soil water tension was maintained at a desired level in the crop root zone at this site due to the flood irrigation events and rainfall, and most likely seepages from the All-American Canal. As a result of the groundwater contribution and shallow water table at site DP6, soil was in a saturated condition at the depth of 150 cm. The applied water (rain + irrigation water) was 1150 mm in this orchard over the 12-month period. Although the average soil water tension varied over time in the top 120 cm of the soil, it never declined below 59.5 kPa including the long period of 11th August through 30th October with no irrigation event and no precipitation. The soil water tension values at 0.30 m and 0.45 m deep exceeded 130 kPa and 70 kPa, respectively, during January and February.

Figure 8.

Half-hourly (a) soil volumetric water content (cm3 cm−3) measured at depths of 30 cm, 60 cm, and 90 cm at the Date Palm 3 (DP3) site and (b) soil water tension (kPa) measured at depths of 30 cm, 45 cm, 60 cm, 90 cm, 120 cm, and 150 cm at the Date Palm 6 (DP6) site. The soil water tension data is reported for the DP6 site to show the soil saturated condition in the deeper depth (150 cm) where no TEROS 12 sensor was available to measure soil volumetric water content. Soil water content at field capacity (FC) and permanent wilting point (PWP) at the site DP3 is approximately 0.09 and 0.23 cm3 cm−3, respectively; and at the site DP6, soil water tension at FC is nearly 13 kPa and at PWP is more than 200 kPa.

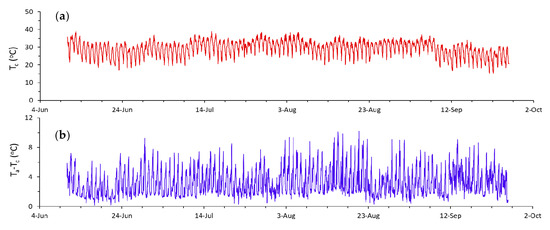

Canopy temperature (Tc) typically follows a diurnal curve that is primarily influenced by the solar radiation cycle (Figure 9a). As an indirect indicator of the plant-water status, the differences between the above canopy air temperature (Ta) and Tc (average temperature recorded by the two IRTs) were calculated on a half-hourly basis. Figure 9b displays Ta − Tc at site DP3 for the summer and early fall 2019. The positive differences indicate that Tc measurements were less than Ta measurements the entire period, with Ta − Tc ranging from 0.7 to 10.1 °C. The largest range in Tc measurements was observed during the mid-afternoon hours, 14:00–14:30, indicating the maximum possible amount of differential stress throughout the day if a water deficit occurred in the crop root zone. The results demonstrate that the minimum Ta − Tc typically happened during the late-afternoon hours, mostly 15:30–16:00, during the summer months.

Figure 9.

Half-hourly (a) canopy temperature and (b) differences between above canopy air temperature and canopy temperature at the DP3 experimental site. The average temperature measured by the two infrared thermometers (IRTs) was considered as canopy temperature and air temperature was measured at a height of about 0.8 m above the top of trees.

Even though high air temperatures were recorded above the canopy at each of the experimental sites, for instance 45.3 °C at site DP3, the Ta − Tc measure always had a positive value in all the date palms except site DP5. Soil moisture variation was similar at all the experimental sites as shown for sites DP3 and DP6. Consequently, the soil water availability at the experimental sites was relatively high and the trees would not likely experience water stress during the study period. It could be assumed that the date palms were fully irrigated over the 12-month period.

3.6. Actual Evapotranspiration

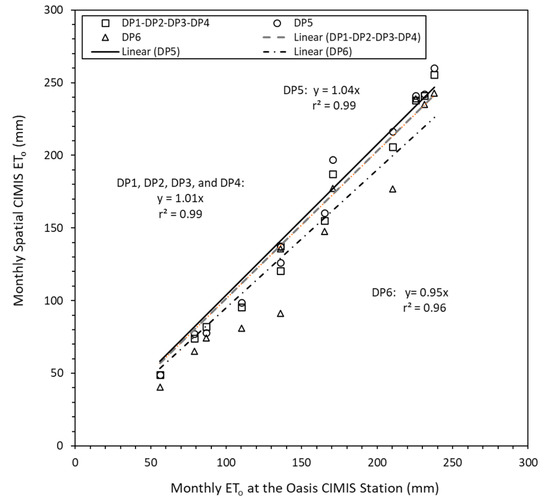

Daily spatial CIMIS ET0 values across the six sites ranged from 0.3 mm day−1 in December to 11.2 mm day−1 in June, while the 12-month totals fell within the range of 1707 (site DP6) to 1884 mm (site DP5; Table 5). The monthly mean spatial CIMIS ETo at the experimental sites varied from 1% (sites DP2-DP3-DP4) to 4% (site DP5) more than the monthly mean to 5% (site DP6) less than the monthly ETo of the Oasis CIMIS station (Figure 10) during the study period. By comparison, the corresponding totals for ETa were 1299 mm at site DP6 and 1310 mm at site DP5. A low cumulative ETa was observed at site DP5, despite of the fact that there was a higher cumulative ETo in this date palm orchard.

Table 5.

Maximum and mean daily actual evapotranspiration (ETa), cumulative actual evapotranspiration (CETa), and cumulative reference evapotranspiration (CETo) at the experimental sites over the 12-month study period (May 2019—April 2020).

Figure 10.

Monthly Spatial CIMIS ETo of the experimental date palms versus monthly ETo at the Oasis # 136 CIMIS station. The difference of spatial CIMIS ETo at DP1-DP4 sites was less than 1%, and as a result only one set of ETo was used to represent the spatial CIMIS ETo of these four sites. The monthly data over the 12-month study period (May 2019–April 2020) were used for this analysis.

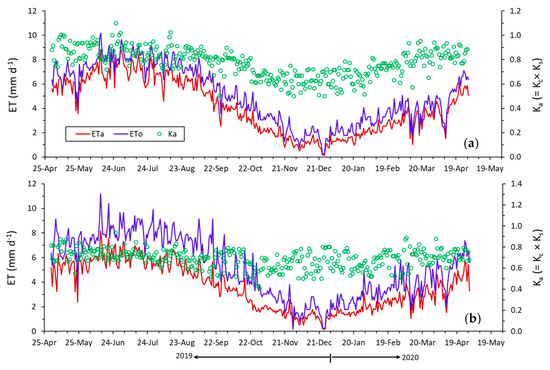

Trivial differences (<3%) were found in the cumulative ETa (CETa) amounts determined across the three sites of DP2, DP3, and DP4, and a mean of 1481 mm was obtained as the CETa for these sites. Daily ETa varied between about 2.9 mm day−1 in February through March (during pollination with a daytime temperature range of 12–23 °C) and about 7.2 mm day−1 in July (at the mature fruit stage of khalal with a daytime temperature range of 27–42 °C). The cumulative ETa was 1501 mm at site DP1, which is about 15% more than the CETa obtained at site DP6. The highest and lowest daily ETa were observed at site DP3 (8.8 mm day−1) on 30 June 2019 and at site DP5 (0.3 mm−1) on 26 December 2019, respectively (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Daily reference evapotranspiration (ETo), actual evapotranspiration (ETa), and actual crop coefficient (Ka) at (a) the DP3 experimental site and (b) site DP5. The results are presented for the 12-month study period (May 2019–April 2020).

The trends of daily Ka values were similar in the experimental orchards over the study period, with more Ka variability during fall and winter months when compared with spring and summer months (Figure 11). A maximum and minimum daily Ka value of 1.17 and 0.50 was obtained at site DP3, respectively. The ETa and Ka values were lower at site DP5 when compared with the corresponding values at site DP3; however, there were no significant differences during December and January. For example, a CETa of 222 mm and 47 mm was observed at site DP3 during a 30-day period of 1 July through 30 July 2019, and 1 January through 30 January 2020, respectively. The CETa values were 188 mm for the July and 49 mm for the January at site DP5. Average Ka values of 0.88 and 0.72 were determined for sites DP3 and DP5 in July, while the mean Ka values were both 0.64 in January.

4. Discussion

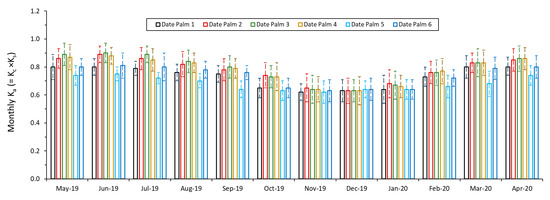

The observed daily ETa and spatial CIMIS ETo in each of the experimental date palm groves were used to compute the monthly Ka values at each site (Figure 12). The results indicate that there is considerable variability in crop coefficient values of date palms, both spatially and temporally. At site DP4, the monthly Ka value varied between 0.64 (SD = 0.1) in December 2019 and 0.88 (SD = 0.06) in June 2019. This flood irrigated orchard has a sandy loam, non-salt affected soil with an average of 81% cover canopy and 11.5 m tree height. There was a mild to moderate water stress experience during July 2019, but soil moisture was maintained during the remainder of the study period.

Figure 12.

Calculated monthly actual crop coefficient (Ka) values at the experimental date palms over the 12-month study period. The observed daily actual evapotranspiration (ETa) and spatial CIMIS reference evapotranspiration (ETo) in each of the experimental date palms were used to compute the monthly Ka values. Standard deviation (SD) of the corresponding Ka values is shown on the bars.

The soil types and conditions at sites DP2, DP3, and DP4 were similar, and the canopy features were similar as well. Both sites DP3 and DP4 had a density of 120 plants ha−1, whereas the density was 124 plants ha−1 at site DP2. All three sites have the ‘Deglet Noor’ date cultivar, slight differences were found among the monthly Ka values of these orchards that are possibly related to irrigation management differences. An integrated irrigation system consisting of drip and flood irrigation was used at sites DP2 and DP3. Both sites are considered fully irrigated orchards over the study period with applied water of 2351 mm at site DP2 and 2420 mm at site DP3, relatively high soil moisture, and relatively cool canopy temperature data. The Ka values for the 12-month period were 0.81, 0.82, and 0.81 at sites DP2, DP3, and DP4, respectively. Within the year, the monthly range of values was from 0.63 (December) to 0.90 (June) at site DP3. These values likely represent the ‘potential’ Kc values for the date palms since the applied irrigation water in these orchards were 50%–60% higher than the measured CETa and both soil moisture and canopy temperature data suggest that no water deficit occurred over the 12-month period.

The monthly Ka value varied from 0.62 (SD = 0.05) in November 2019 to 0.75 (SD = 0.08) in June 2019 at site DP5, a silty clay loam saline-sodic orchard with an average of 55% cover canopy, density of 148 plants ha−1, and 7.3 m tree height. This orchard is regularly irrigated by a microsprinkler and occasionally flood irrigated to leach out heavy salt accumulated in the entire soil profile.

Across the six sites, DP3 and DP5 had the highest and lowest Ka values averaged over the 12-month period, respectively. An average 12-month Ka value of 0.70 was obtained at site DP5, which is nearly 17% lower than the average 12-month Ka value of site DP3. Both sites had the same date cultivar; however, site DP5 had a higher planting density and smaller trees. The reduction of tree growth at site DP5 is associated with the physiologic adjustment of trees to the long exposure to high salinity–sodicity environments. Earlier studies indicated that all aspects of date palm vegetative growth may negatively respond to salinity including the rate of production of new leaves and the size of the leaf canopy but at the same time salinity may increase the crop water consumption [46,47,48]. The percentage of light interception was 30% lower in the date palm irrigated by saline water (15.0 dS m−1) in a recent study conducted by Al-Muaini et al. [15]. A similar effect of salinity on crop ET and tree growth was reported by Marino et al. [44] for pistachio orchards grown on saline soils in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

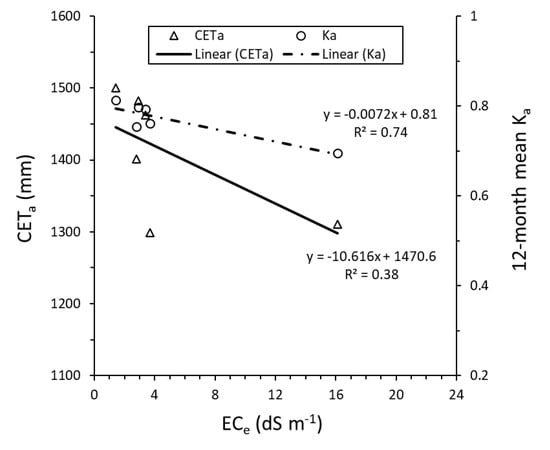

To quantify the impacts of salinity on date palm crop water use, the relations of cumulative ETa and mean annual actual crop coefficient as a function of ECe were derived. Inverse relationships were found between the CETa and ECe; and between the mean annual Ka and ECe (Figure 13). The average ECe of the entire soil profile (1.2 m depth) from the soil samples at each date palm site were used in this analysis to represent an average ECe for the corresponding orchards. A better correlation was obtained between the mean Ka and ECe (linear relationship of −0.0072 × ECe + 0.81 with a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.74) than the linear relationship derived between CETa and ECe (−10.616 × ECe + 1470.6 with a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.38) in a wide range of ECe (1.4 dS m−1 < ECe < 16.1 dS m−1). As was mentioned earlier, other drivers are involved in ETa and Ka values including canopy features and cultivars, soil types, and irrigation management practices. These parameters do not directly contribute to the observed linear relationships; however, they indirectly impact the results. For instance, the reduced vegetative growth at site DP5 site may have resulted from the salinity and drainage issues, and the soil properties. The soil is categorized “silty loam” with silt content greater than 50% at the top 1.2 m, and therefore, it has a very low infiltration rate.

Figure 13.

The relationship of cumulative actual evapotranspiration (CETa) and mean annual actual crop coefficient (Ka) versus electrical conductivity of the saturation extract (ECe). The average ECe of the entire soil profile (1.2 m depth) from the whole soil samples at each date palm site were used to represent the average ECe of crop root zone in each of the experimental sites.

A seasonal comparison of date palm Ka values obtained in the present study with the ones reported by other researchers is given in Table 6. Making direct comparisons of the results of these attempts is complicated because a range of techniques with different assumptions has been used and the studies were conducted under different conventional irrigated and high-water table conditions. Obvious differences were found in Ka values. The mean monthly actual coefficient values in this work ranged between 0.62 and 0.90. Higher crop coefficient values were 0.75–1.10 from Mazahrih et al. [13], 0.90–0.95 from Allen et al. [32], and 0.70–1.00 from FAO [16]. The fixed Ka = 0.85 reported by Alazba [49] for date palm in Saudi Arabia is similar (<3% different) to the mean annual Ka value obtained for the three date palm orchards with the highest Ka values amongst the six date palm orchards studied in this work. A lower and narrower range of Ka from 0.63 to 0.70 was also suggested by Kassem [12] in Saudi Arabia. The lowest Ka = 0.29 was reported by Al-Muaini et al. [15] in UAE using sap flow measurements. The Ka was reduced to 0.20 in a date palm irrigated with saline water (15.0 dS m−1).

Table 6.

Comparison of crop coefficient estimates by this study and the values proposed by other researchers for date palm.

5. Conclusions

It is widely recognized that increasing demands for water in Southern California are affected by actions to reduce and redirect the amount of water imported from the Colorado River. A serious concern is that the demand for this precious natural resource is increasing, while the water resource availability is decreasing. Dates are one of the higher water-use crops in the California low desert region where the application of more accurate crop coefficients may provide an essential tool for determining water-balance information to assist in optimizing irrigation water management. This study aimed at investigating actual crop water use and crop coefficients in date palm production systems in California and understanding their relations with the soil and crop canopy features.

The results from six commercial date palm groves demonstrated clearly that water consumption of date palm varies considerably depending upon site-specific conditions. Across the experimental sites, the 12-month actual ET totals fell within the range of 1299–1501 mm. The corresponding mean daily ETa was 3.6 mm day−1 and 4.1 mm day−1, respectively. A maximum and minimum daily Ka value of 1.17 and 0.50 was observed. A mean 12-month Ka = 0.70 was determined for a silty-clay loam, saline-sodic soil, while a Ka = 0.80 was found for a non-salt-affected, sandy loam soil. A mean of Ka = 0.83 was estimated for April through July, which is about 28% higher than the mean Ka value estimated for November through January.

The findings of this ongoing research may assist growers in employing adaptive tools and water management practices that support efficient and sustainable date palm production and optimize use of water resources. The derived monthly Ka represents coefficients for date palms except in the salt-affected orchard, which experienced a high level of salinity stress. For salt affected orchards a stress coefficient is needed to account for salinity effects on ETa. This Ka enables growers to determine date palm water needs in a reliable, usable, and affordable format, as well as benefits local irrigation districts with their water delivery and conservation programs.

The results are likely applicable to other locations having similar climate to the low desert region of California, as well as orchards with similar varieties, irrigation practices, and canopy and soil features. While this is an ongoing project and the results will be completed and verified over time and when more data are available, a few cautionary notes need to be considered with the results reported and the analysis accomplished in this article:

- -

- Since the ET of date palms is likely reduced from its potential, the ET measured is referred as observed or actual ET (ETa), which is limited by water deficits and salinity in addition to energy limited, whereas the potential crop ET (ETc) is limited by energy availability to vaporize water and not soil hydrology or salinity. The values reported in this paper are actual crop coefficients that are calculated as: Ka = ETa/ETo rather than standard crop coefficients expressed as: Kc = ETc/ETo. This approach was used because it is difficult to find a date palm grove in a desert region that does not experience some water and/or salinity stress during a year.

- -

- Spatial CIMIS ETo was used rather than the ETo of one individual CIMIS station in the region. The variability in the ETo might be a factor causing differences in Ka for the various date palm orchards. In this study, the monthly spatial CIMIS ETo at the experimental sites varied from 1 to 4% more to 5% less than the monthly mean ETo of the Oasis CIMIS station, which was the closest station to the six orchards.

- -

- Various factors could impact the variability of Ka including irrigation management practices, salinity and/or soil differences, groundwater table, height of trees, and percentage ground shading (likely most important driver) that provides a good estimation of canopy size/volume and the amount of light that it can intercept.

Three experimental sites were close to airport and the flights had to be conducted in low altitude to prevent interference with the airport. As a result, the aerial images were inadequate to produce an accurate densified point cloud and the crop cover estimates. While it is hard to retrieve a reliable quantitative relation between the canopy features and the Ka values at this moment, the dependency is obvious. Further aerial imagery data acquisition and/or ground-based light interception measurements are required to evaluate such relationship/s scientifically.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., R.K. and R.L.S.; Data curation, A.M., D.C. and A.P.; Formal analysis, A.M., R.L.S. and A.P.; Funding acquisition, A.M.; Investigation, A.M., C.L. and S.R.; Methodology, A.L., C.L. and R.L.S.; Resources, A.M., C.L. and R.L.S.; Supervision, A.M.; Writing—Original draft, A.M.; Writing—Review and editing, A.M., R.K., R.L.S., D.C., A.P., C.L. and S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this research (Improving Date Palm Water Use Efficiency Through Updated Crop Water Use Information and Irrigation Practices) was made possible by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Agricultural Marketing Service through Grant AM180100XXXXG003. The contents presented in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the USDA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the California Date Commission for providing supports and thoughts, and gratefully acknowledge Hadley Date Gardens, Kohl Ranch, Royal Medjool Growers, and Be Sweet Citrus for allowing us to implement this project on their orchards. Finally, the authors wish to acknowledge the technical support of Tayebeh Hosseini and Tait Rounsaville, whose conscientious works in the field and in the laboratory were crucial to the success of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zohary, D.; Hopf, M. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley; Oxford University Press: Oxon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Montazar, A. Best irrigation management practices in California date palm. UC ANR Knowledge Stream, 30 September 2019. Available online: https://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=31434 (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Abdul-Baki, A.A.; Aslan, S.; Linderman, R.; Cobb, S.; Davis, A. Soil, Water and Nutritional Management of Date Orchards in the Coachella Valley and Bard, 2nd ed.; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- Jaradat, A.; Zaid, A. Quality traits of date palm fruits in a center of origin and center of diversity. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2004, 2, 208–217. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Amoud, A.I.; Bacha, M.A.; Al-Darby, A.M. Seasonal water use of date palm in the central region of Saudi Arabia. Agric. Eng. J. 2000, 9, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment and Water (MOEW). State of Environment Report 2015. United Arab Emirates; 2015; p. 36. Available online: www.moew.gov.ae (accessed on 14 June 2015).

- Allen, R.G.; Pruitt, W.O.; Wright, J.L.; Howell, T.A.; Ventura, F.; Snyder, R.L.; Itenfisu, D.; Steduto, P.; Berengena, J.; Baselga Yrisarry, J.; et al. A recommendation on standardized surface resistance for hourly calculation of reference ETo by the FAO 56 Penman-Monteith method. Agric. Water Man. 2006, 81, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payero, J.O.; Neale, C.M.U.; Wright, J.L.; Allen, R.G. Guidelines for validating Bowen ratio data. Trans. ASAE 2003, 46, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, H.J.; Howell, T.A.; Shuttleworth, W.J.; Bausch, W.C. Evapotranspiration: Progress in measurement and modelling in agriculture. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Howell, T.A.; Jensen, M.E. Evapotranspiration information reporting: I. Factors governing measurement accuracy. Agric. Water Manag. 2011, 98, 899–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furr, J.R.; Armstrong, W.W. The seasonal use of water by Khadrawy date palms. Date Grow. Inst. Rep. 1956, 23, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kassem, M.A. Water requirements and crop coefficient of date palm trees ‘Sukriah cv’. MISR J. Agric. Eng. 2007, 24, 339–359. [Google Scholar]

- Mazahrih, N.T.; Al-Zu’bi, Y.; Ghnaim, H.; Lababdeh, L.; Ghananeem, M.; Ahmadeh, H.A. Determination actual evapotranspiration and crop coefficients of date palm trees (Phoenix dactylifera) in the Jordan Valley. Am. Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2012, 12, 434–443. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Aïssa, I.; Bouarfa, S.; Perrier, A. Utilisation de la mesure thermique du flux de sève pour l’évlauation de la transpiration d’un plmier dattier. In Economies d’Eau en Systèmes Irrigués au Maghreb; Hartani, T., Douaoui, A., Kuper, M., Eds.; Actes du quatrième atelier régional du projet Sirma, Mostaganem, Algéria; CIRAD: Montpellier, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Muaini, A.; Green, S.; Dakheel, A.; Abdullah, A.; Abou-Dahr, W.; Dixon, S.; Kemp, P.; Clothier, B. Irrigation management with saline groundwater of a date palm cultivar in the hyper-arid United Arab Emirates. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 211, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Regional Office for the Near East. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Irrigation of Date Palm and Associate Crops, Chapter 1 (Irrigated Date Palm Production in the Near East), Damascus, Syrian Arab Republic, 27−30 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, D. Date Palms for Australia- Future Developing the Industry; Nuffield Australia: Moama, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tolk, J.A.; Howell, T.A.; Evett, S.R. An evapotranspiration research facility for soil-plant-environment interactions. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2005, 21, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.L.; Spano, D.; Paw U, K.T. Surface Renewal analysis for sensible and latent heat flux density. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 1996, 77, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spano, D.; Snyder, R.L.; Duce, P.; Paw U, K.T. Surface renewal analysis for sensible heat flux density using structure functions. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1997, 86, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.; Massman, W.J.; Law, B.E. Handbook of Micrometeorology: A Guide for Surface Flux Measurement and Analysis; Kluwer: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Massman, W.J.; Lee, X. Eddy covariance flux corrections and uncertainties in long-term studies of carbon and energy exchanges. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2002, 113, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.H.; Snyder, R.L. Evaporation and eddy covariance. In Encyclopedia of Water Science; Stewart, B.A., Howell, T., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paw U, K.T.; Snyder, R.L.; Spano, D.; Su, H.B. Surface renewal estimates of scalar exchange. In Micrometeorology in Agricultural Systems; Hatfield, J.L., Baker, J.M., Eds.; Agronomy Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2005; pp. 455–483. [Google Scholar]

- Montazar, A.; Rejmanek, H.; Tindula, G.N.; Little, C.; Shapland, T.M.; Anderson, F.E.; Inglese, G.; Mutters, R.G.; Linquist, B.; Greer, C.A.; et al. Crop coefficient curve for paddy rice from residual of the energy balance calculations. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2017, 143, 04016076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapland, T.M.; McElrone, A.J.; Paw U, K.T.; Snyder, R.L. A turnkey data logger program for field-scale energy flux density measurements using eddy covariance and surface renewal. Ital. J. Agrometeorol. 2013, 1, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Paw U, K.T.; Qiu, J.; Su, H.B.; Watanabe, T.; Brunet, Y. Surface renewal analysis: A new method to obtain scalar fluxes without velocity data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1995, 74, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Atta, C.W. Effect of coherent structures on structure functions of temperature in the atmospheric boundary layer. Arch. Mech. 1977, 29, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Twine, T.E.; Kustas, W.P.; Norman, J.M.; Cook, D.R.; Houser, P.R.; Meyers, T.P.; Prueger, J.H.; Starks, P.J.; Wesely, M.L. Correcting eddy-covariance flux underestimates over a grassland. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2000, 103, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapland, T.M.; Snyder, R.L.; Paw U, K.T.; McElrone, A.J. Thermocouple frequency response compensation leads to convergence of the surface renewal alpha calibration. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 189, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Walter, I.A.; Elliott, R.L.; Howell, T.A.; Itenfisu, D.; Jensen, M.E.; Snyder, R.L. The ASCE Standardized Reference Evapotranspiration Equation; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2005; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, D.A. Thermal properties of soil. In Physics of Plant Environment; van Wijk, W.R., Ed.; North-Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1963; pp. 210–234. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, R.L.; Pedras, C.; Montazar, A.; Henry, J.M.; Ackley, D.A. Advances in ET-based landscape irrigation management. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 147, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIMIS. Available online: http://wwwcimis.water.ca.gov/SpatialData.aspx (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Pruitt, W.O.; Doorenbos, J. Empirical calibration a requisite for evapotranspiration formulae based on daily or longer mean climatic data. In Proceedings of the International Round Table Conference on “Evapotranspiration”, Budapest, Hungary, 26–28 May 1977; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Birdal, A.C.; Avdan, U.; Türk, T. Estimating tree heights with images from an unmanned aerial vehicle. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2017, 8, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourreza, A.; Zuniga-Ramirez, G.; Zhang, X.; Cheung, K. Almond yield prediction using fusion of canopy profile and spectral features extracted from aerial imagery. Unpublished Article. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Corwin, D.L.; Lesch, S.M. Application of soil electrical conductivity to precision agriculture: Theory, principles, and guidelines. Agron. J. 2003, 95, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L.; Lesch, S.M. Characterizing soil spatial variability with apparent soil electrical conductivity: I. Survey protocols. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2005, 46, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L.; Lesch, S.M. Apparent soil electrical conductivity measurements in agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2005, 46, 11–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L.; Scudiero, E. Field-scale apparent soil electrical conductivity. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Logsdon, S., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tompson, A.; Demir, Z.; Moran, J.; Mason, D.; Wagoner, J.; Kollet, S.; Kayyum, M.; McKereghan, P. Groundwater Availability Within the Salton Sea Basin; Report LLNL-TR-400426; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory: Livermore, CA, USA, 2008.

- Marino, G.; Zaccaria, D.; Snyder, R.L.; Lagos, O.; Lampinen, B.D.; Ferguson, L.; Grattan, S.R.; Little, C.; Shapiro, K.; Maskey, M.; et al. Actual evapotranspiration and tree performance of mature micro-irrigated pistachio orchards grown on saline-sodic soils in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Agriculture 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapland, T.M.; Snyder, R.L.; Smart, D.R.; Williams, L.E. Estimation of actual evapotranspiration in wine grape vineyards located on hillside terrain using surface renewal analysis. Irrig. Sci. 2012, 30, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, N.; Martínez-Cob, A. Evaluation of the surface renewal method to estimate wheat evapotranspiration. Agric. Water Manag. 2002, 55, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripler, E.; Ben-Gal, A.; Shani, U. Consequence of salinity and excess boron on growth, evapotranspiration and ion uptake in date palm (Phoenix dactylifera, L.; cv. Medjool). Plant Soil 2007, 297, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripler, E.; Shani, U.; Mualem, Y.; Ben-Gal, A. Long-term growth, water consumption and yield of date palm as a function of salinity. Agric. Water Manag. 2011, 99, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazba, A. Estimating palm water requirements using Penman-Monteith mathematical model. J. King Saud Univ. Agric. Sci. 2004, 16, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).