1. Introduction

The Global Risk Report identifies water crises having the fourth most significant societal impact after weapons of mass destruction, climate change and extreme weather events, ahead of natural disasters [

1]. Water, a basic human need and right, permits human functioning and activity, allowing for improved standard of living, as well as improve the agricultural, industrial and service sector productive capacities [

2]. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 addresses drinking water resources, with an endeavour to achieve “universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all” by 2030. However, there is also recognition that water affects the entire global development agenda [

3,

4]. In that light, SDG 5 avers to end barriers preventing women and girls from realising their full potential [

5]. In achieving both SDGs 5 and 6, it is peculiar that women and girls are responsible in providing water security. A report by UN Women [

6] actually identifies that women are not only central in water security, but across all the 17 SDGs.

The majority of the 1.2 billion poor people worldwide, with two thirds being women, and mostly located in Sub Sahara Africa (SSA) and South Asia, do not have access to safe and reliable sources of water [

7,

8]. Six hundred and sixty-three million people worldwide (with some estimates running up to 785 million) are officially recognised as having no access to an improved drinking water source [

9,

10,

11]. This has been exacerbated by rapid population growth (expected to triple by 2050), urbanization, increased pollution and changing lifestyles, which enhance the gap between supply and demand of water. By the end of the 21st century, water demand in many SSA countries is projected to double [

12].

South Africa is the 30th driest country, described as being water scarce with uneven distribution across the country [

13,

14]. The country is divided into 19 water management areas (WMAs) for management purposes [

15]. In 60% of these WMAs, the country is already using 98% of its existing water supplies [

16]. South Africa had 7.1 million people without basic water supply in 2000, which decreased to 5.4 million in 2004 further decreasing to 4.2 million in 2017 [

17]. This has been attributed to heavy investment in water infrastructure since 1994, with over 4395 registered dams [

18,

19]. The average person uses 25 L of water a day, with projections that water use in the country will rise to 30 billion cubic metres per year by 2030 [

16]. Maintaining the current water usage in the country will result in a 17% water deficit by 2030 [

20]. Due to the country’s political history and cognisance of the country’s racial and gender discrimination, resulting in conflict of water use, inadequate water supply and slow progress towards promotion of equitable distribution, equity is a strong driver on water policy in South Africa [

14,

21]. However, water related policy such as the 1994 White Paper on Water Supply and Sanitation, the White Paper on National Water Policy and the 1997 Water Services Act 108, have paid lip-service to the gender perspectives in terms of water security [

22,

23].

There exists differentiated relationships to water access, use, knowledge, governance and experiences between men and women, mainly based on gendered division of labour associating women with water [

24]. The relationship between water and gender plays out in four ways [

25]: (a) mirroring gender inequalities in forms such as control and ownership of assets, employment, exposures to risk and decision making, (b) unique and gendered nonmonetary and noneconomic values, (c) solidification of the status quo through noneconomic and nonmonetary values, having differential effect on men and women, and (d) equalizing gender relations in water influencing overall gender equality. Globally, women and girls are responsible for water collection in 80% of the households which have no water on their premises [

5,

26]. However, women are disproportionately affected by resource scarcity, with global indicators on water access not reflecting the gender-disaggregated benefits and burdens. For instance, a report by UN [

27] identifies that in SSA, women spend 16 million hours a day collecting water, whilst men and children spend 6 million and 4 million per day, respectively. At a more individualistic level, women and girls spend between 3 min and 3 h per day collecting water [

8]. This is time foregone in pursuit of agricultural and livelihood activities. Furthermore, the girl child’s school attendance can be improved by 12% if the time taken to fetch water is reduced by 50%. This puts into question the celebrated achievement of the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 7, of halving the proportion of the population with access to safe drinking water by 2015 [

28].

Due to their proximity and activities concerning water, women are vulnerable to water insecurity through exposures to water-borne diseases, fatigue from physically carrying water and exposure to sexual and physical harassment, amongst others [

28]. Proximity to treated water and their wellbeing also has an effect on their sensitivity and adaptive capacity to water insecurity. The great distances, difficult terrain and heavy lifting expose women to vulnerabilities of water insecurity. However, few studies have quantified the vulnerabilities and burdens on women, with a few taking a phenomenological qualitative approach [

26,

29]. Vulnerability studies have also been scanty in the water security realm, with most studies taking linear forms of either quantifying exposures, sensitivities or adaptive capacities in climate change studies. Most water security studies have quantified vulnerabilities through use of indices, such as the Falkenmark water stress index, the Water Resources Vulnerability Index, the Water Poverty Index, the Household Water Insecurity Access Scale (HWIAS) whilst others have used measures such as the Consumption Water Footprint (CW) and the Production Water Footprint (PW), amongst others [

21,

30,

31]. There are limited studies on the pathways between water insecurity and supply, as well as the complexities surrounding patterns of water availability, access and use [

32]. A few studies have tried to operationalize the relationship between the water security attributes [

21,

32,

33]. Fewer still have tried to incorporate gender inequality in these studies [

31,

34]. Observing that women spend more time on water related issues underscores that in order to attain sustainable benefits and unlock the potential of half the global society, emphasis should be placed on female related activities [

27]. The current study argues for the need of a water insecurity vulnerability assessment especially for women into research agendas as well as policy interventions, monitoring and evaluation. The study aims to identify and provide pathways through which female-headed households are water insecure. Value and choice of water is differentiated according to its attributes (quality, affordability, reliability and availability), dependent on the intended use [

10]. The country’s National Water and Sanitation Master Plan as well as the National Water Resource Strategy recognise that it is the prerogative of the water sector to provide universal and equitable access to reliable water supply as enshrined in the country’s National Water Act and the Water Services Act [

35]. However, narrowly focussing on the supply side of water does not guarantee equitable access to satisfy demand especially for disadvantaged classes such as women. The current study is not antagonistic and does not dispel institutional capacitation in providing equitable access to water. The study, however, reinforces the need for better identification of need for female-headed households, with tier benefits of achieving water security, and equitably.

1.1. Conceptual Frameworks

1.1.1. Drinking Water Decision Framework

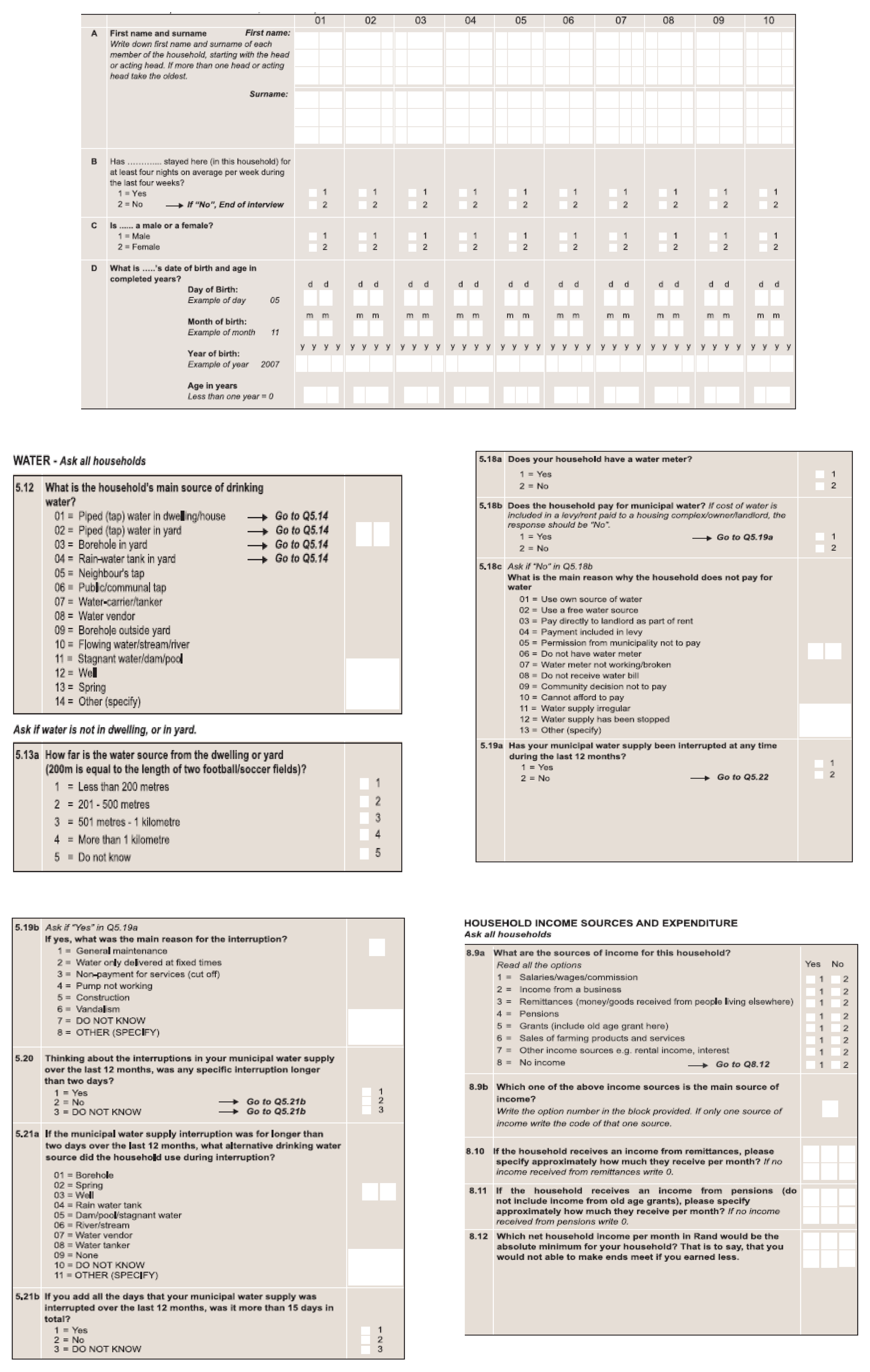

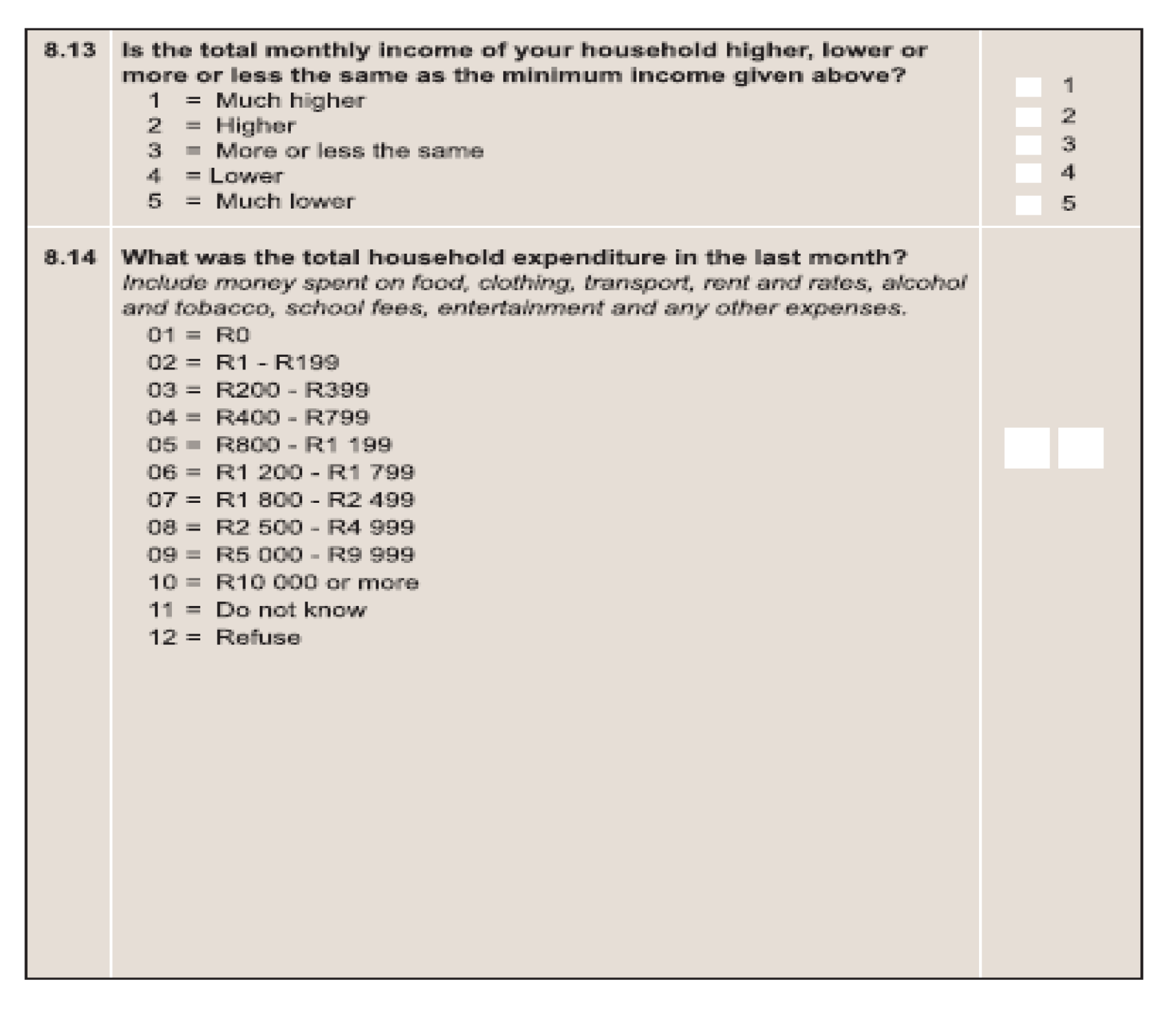

There are various drinking water sources available to households in South Africa. However, various factors mediate people’s ability to access these different sources of water (

Figure 1). Women are responsible for collecting water, even though place and time decision may be influenced by the spouse or adult male in the household. The initial decision will depend on the source of water available to the household as depicted by

Figure 1.

A series of factors related to the source (e.g., cost and reliability of the water source) as well as socio-economic (e.g., ability of the household to afford water and perceptions towards its safety) that will shape decision making concerning which source of water to access [

10]. The peripheral ring from

Figure 1 shows the competing livelihood decision making relative to drinking water. Thus decisions pertaining to drinking water collection are complex and multi-dimensional. The socio-cultural factors in the context of the study refer to the role women play in water decision making. Distance to water sources act as determinants to the quantity of water. This is also influenced by the risk associated with these distances. Competing demands may influence the ability to queue for water, and thus encourage use of expedient sources even if they are of a lower quality. Intermittent water supplies can influence water collectors to seek more reliable water sources, even if it is of a lower quality [

10,

36]. Unreliable water supply prompts people to adapt through coping strategies such as storing water and drilling wells and boreholes [

37]. Unreliability of water results in more prioritisation towards drinking with less towards other important tasks, like washing hands. Households without piped connections often pay more for their water than those with a connection. The high cost of water means that households will not consume as much safe water as they need [

10]. According to Price et al. [

10], the actual or perceived quality of water is key in decision making about drinking water.

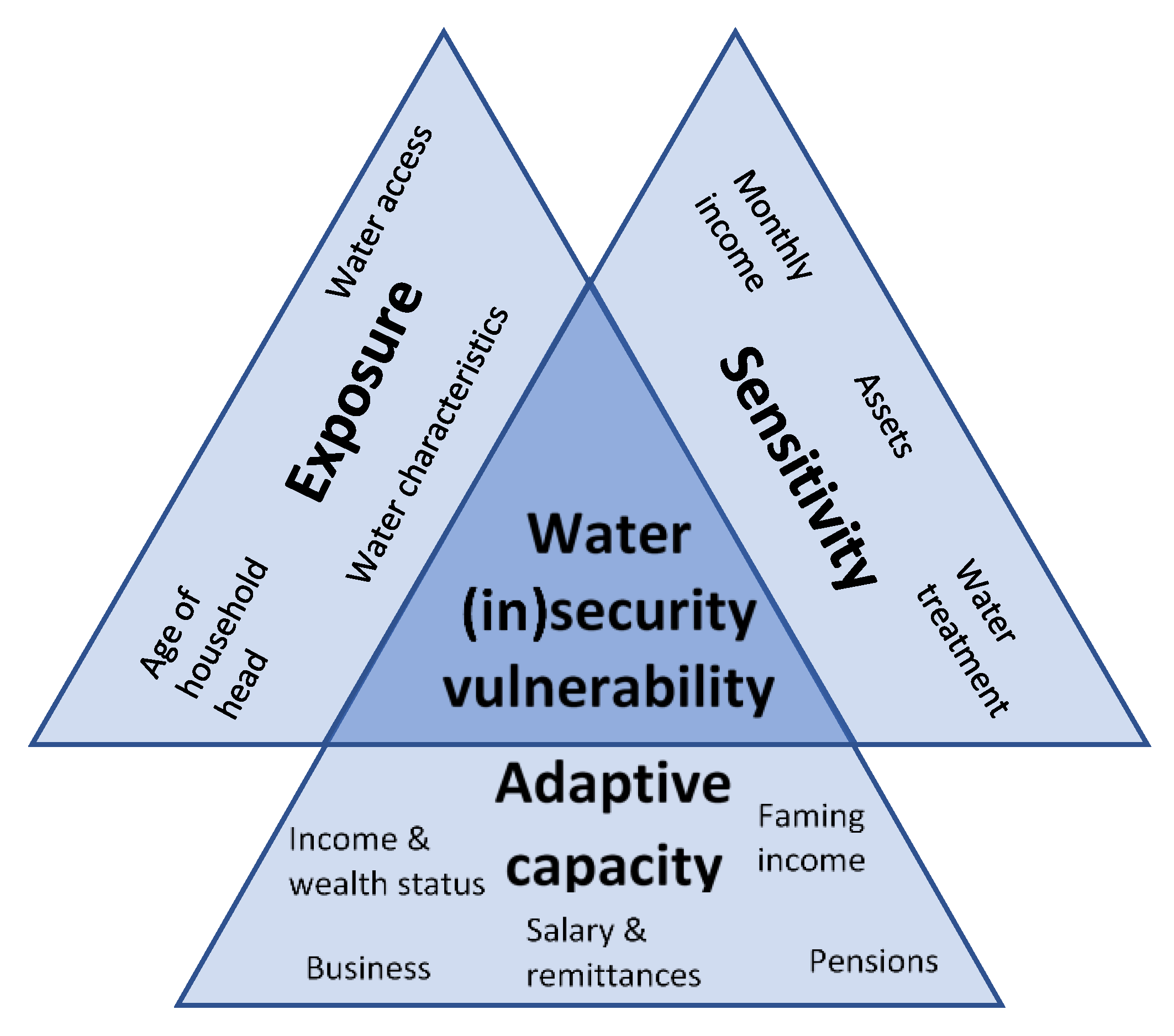

1.1.2. Vulnerability Framework

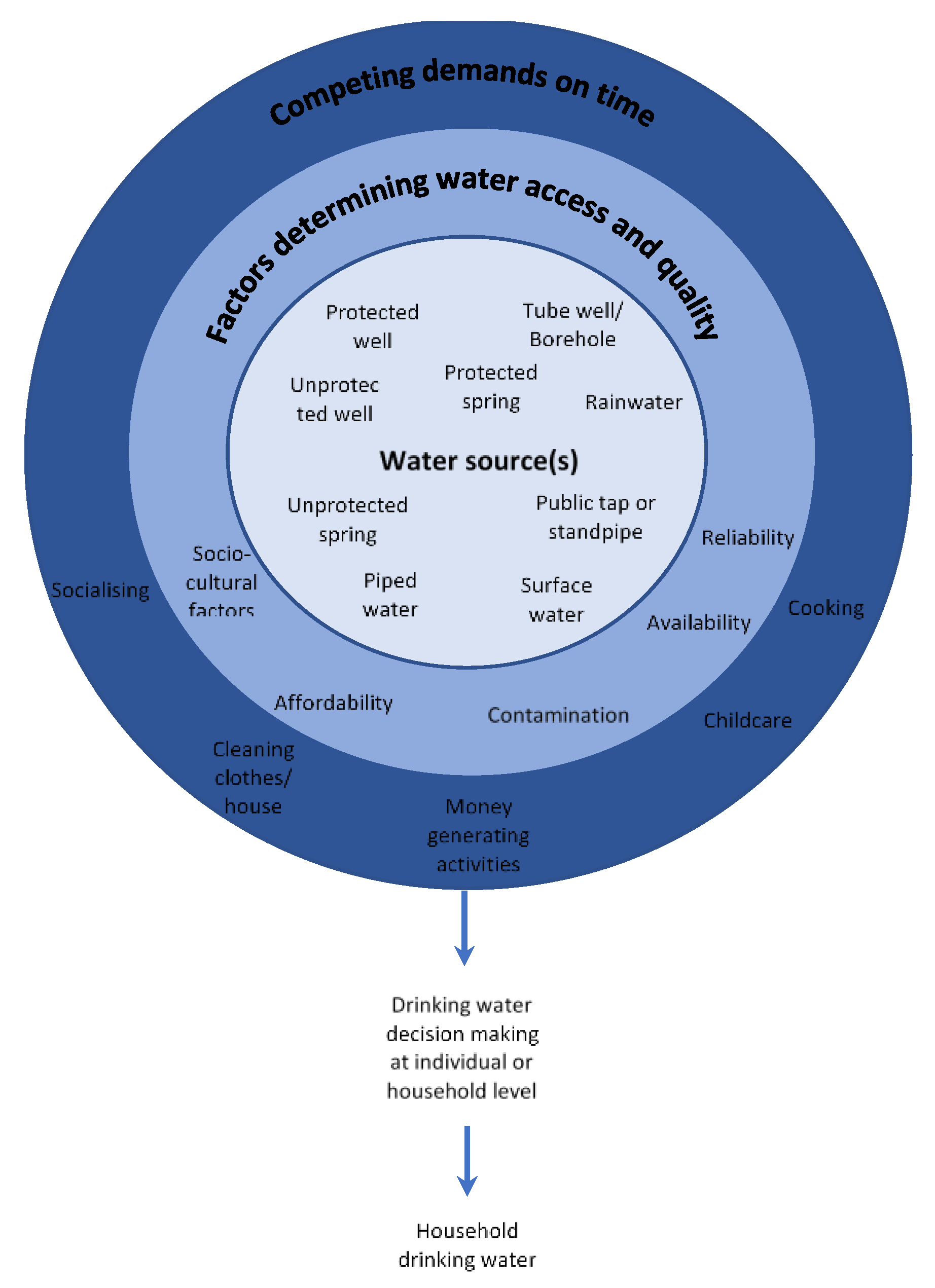

Vulnerability can be utilised in a wide range of contexts, systems and hazards [

38]. In the context of the current study, it takes a social science point of view, depicting the set of socio-economic elements determining people’s ability to cope with stress or change [

39]. In the current study, hazards will refer to physical manifestation of water insecurity, through compromised access, availability and use. Vulnerability is a function of exposure to a stressor, impact (sensitivity or effect) and adaptive capacity (resilience or recovery potential) [

40]. Vulnerability focusses on the exposure to water insecurity, the likelihood or frequency of occurrence of the water insecurity and the sensitivity to the impact of water insecurity. In particular, social vulnerability arises purely from the inherent properties of its internal characteristics. Social vulnerability is determined by factors representing economic well-being, preparedness and coping with respect to water insecurity. The typical vulnerability assessment measure, mostly used in climate change studies, follows the linear form as exhibited by

Figure 2a. However, the current study argues that this linear approach does not highlight the relationships between the constructs of the vulnerability measures, which might be multi-directional/dimensional. Hence, the study will employ a dynamic vulnerability framework as shown in

Figure 2b.

Figure 2b shows that there are multi-directional associations between exposures, sensitivities and adaptive capacities to water insecurity, which are at play in the vulnerability realm. An equilibrium will need to be reached to ascertain the vulnerability to water insecurity.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

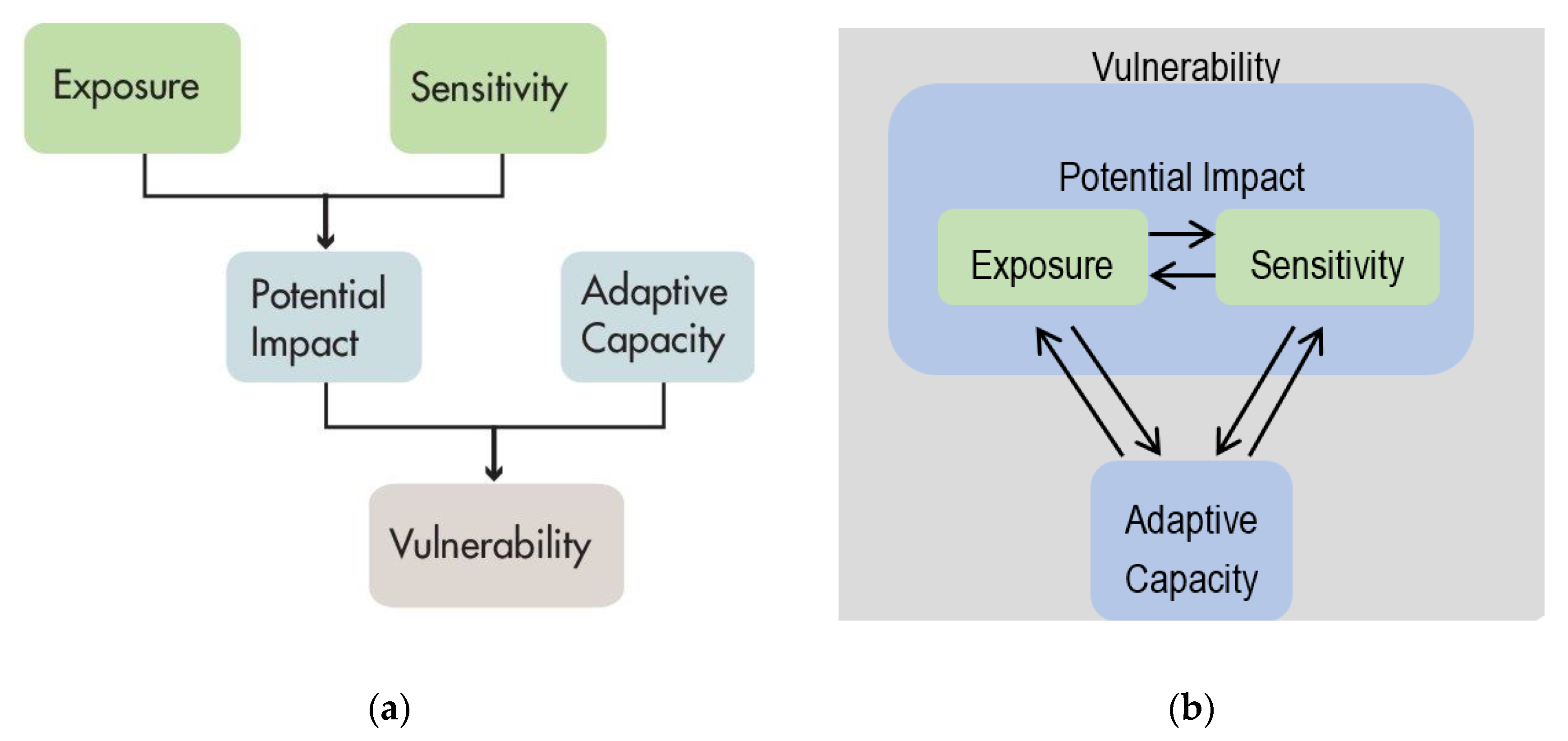

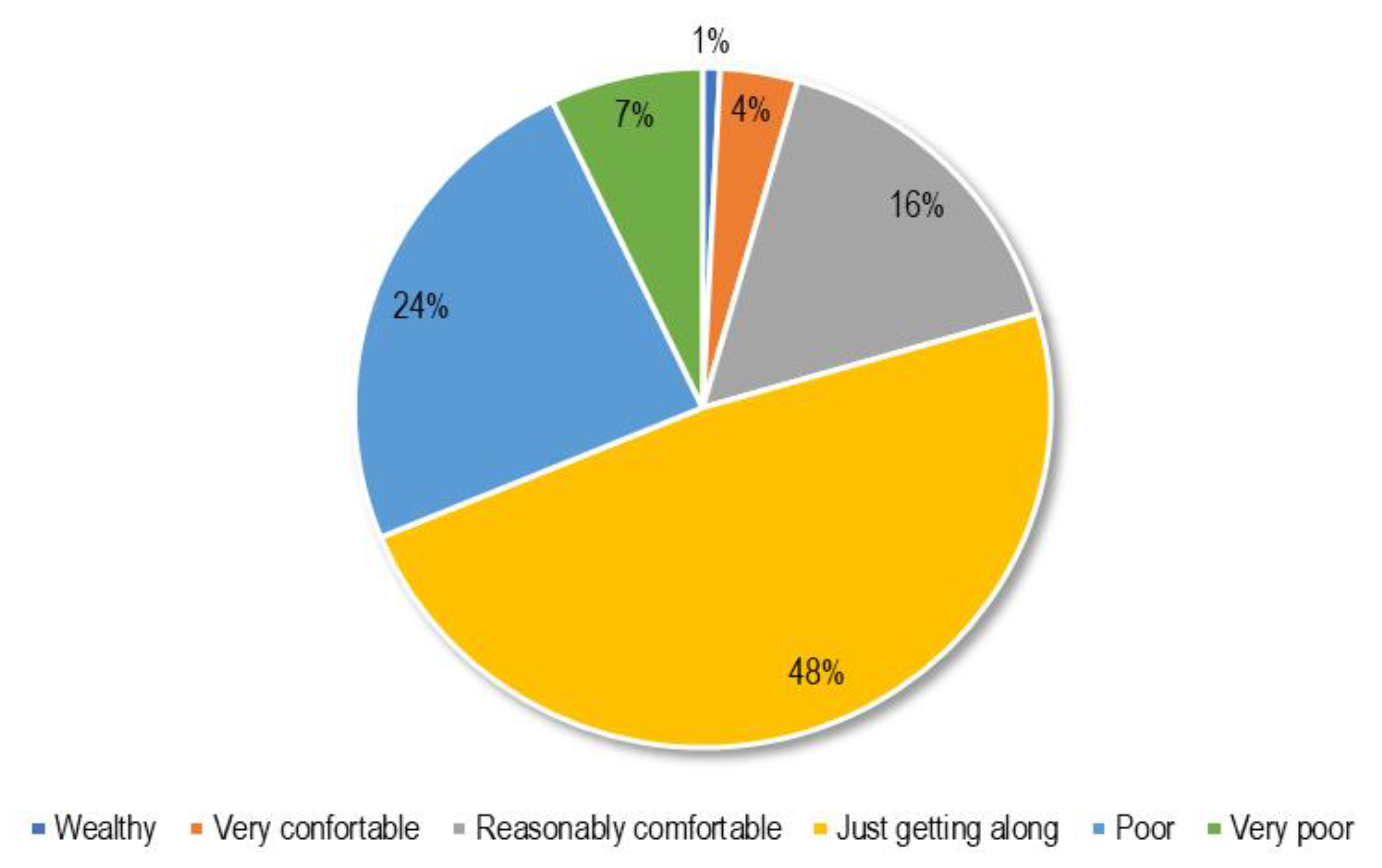

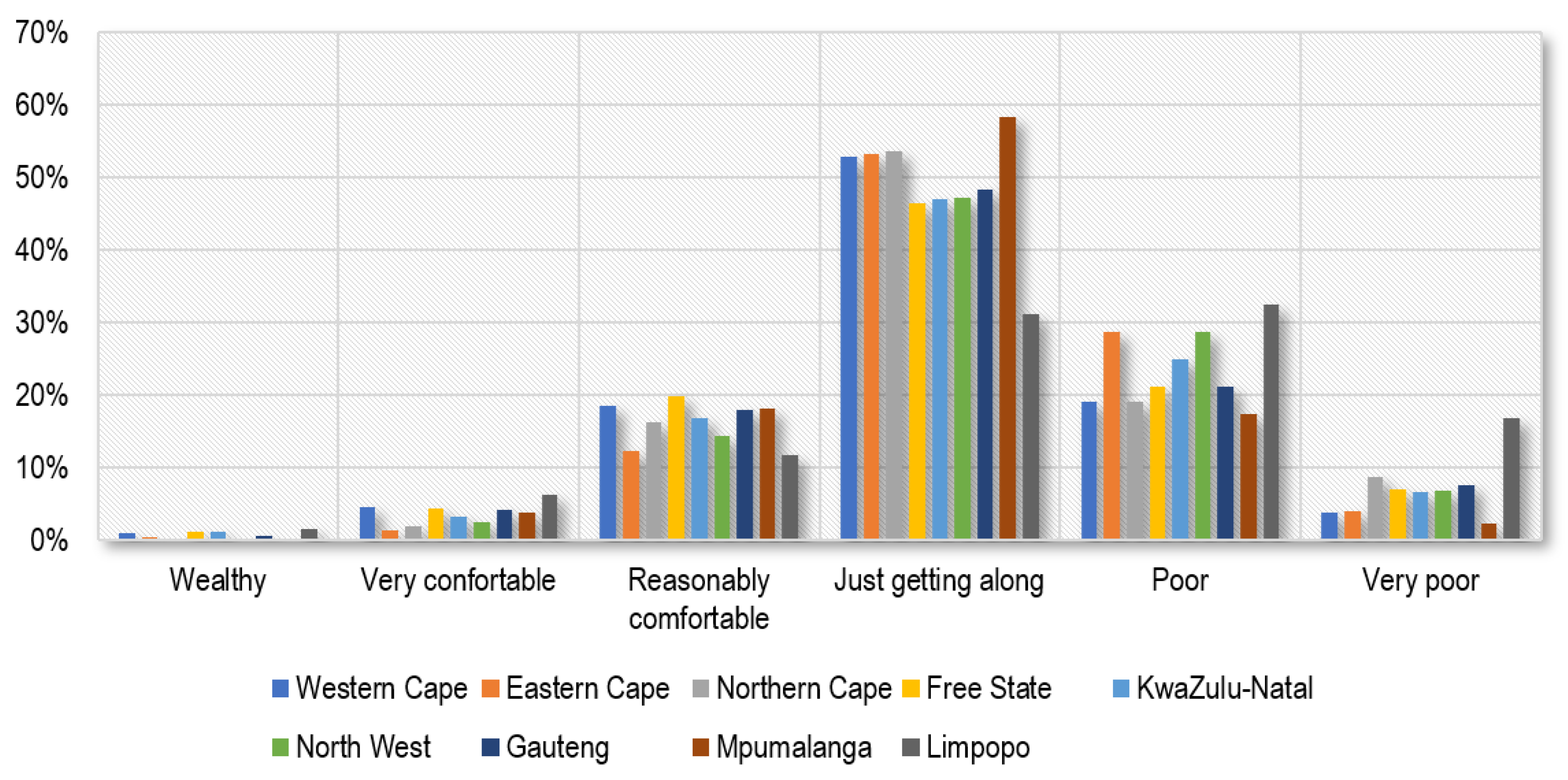

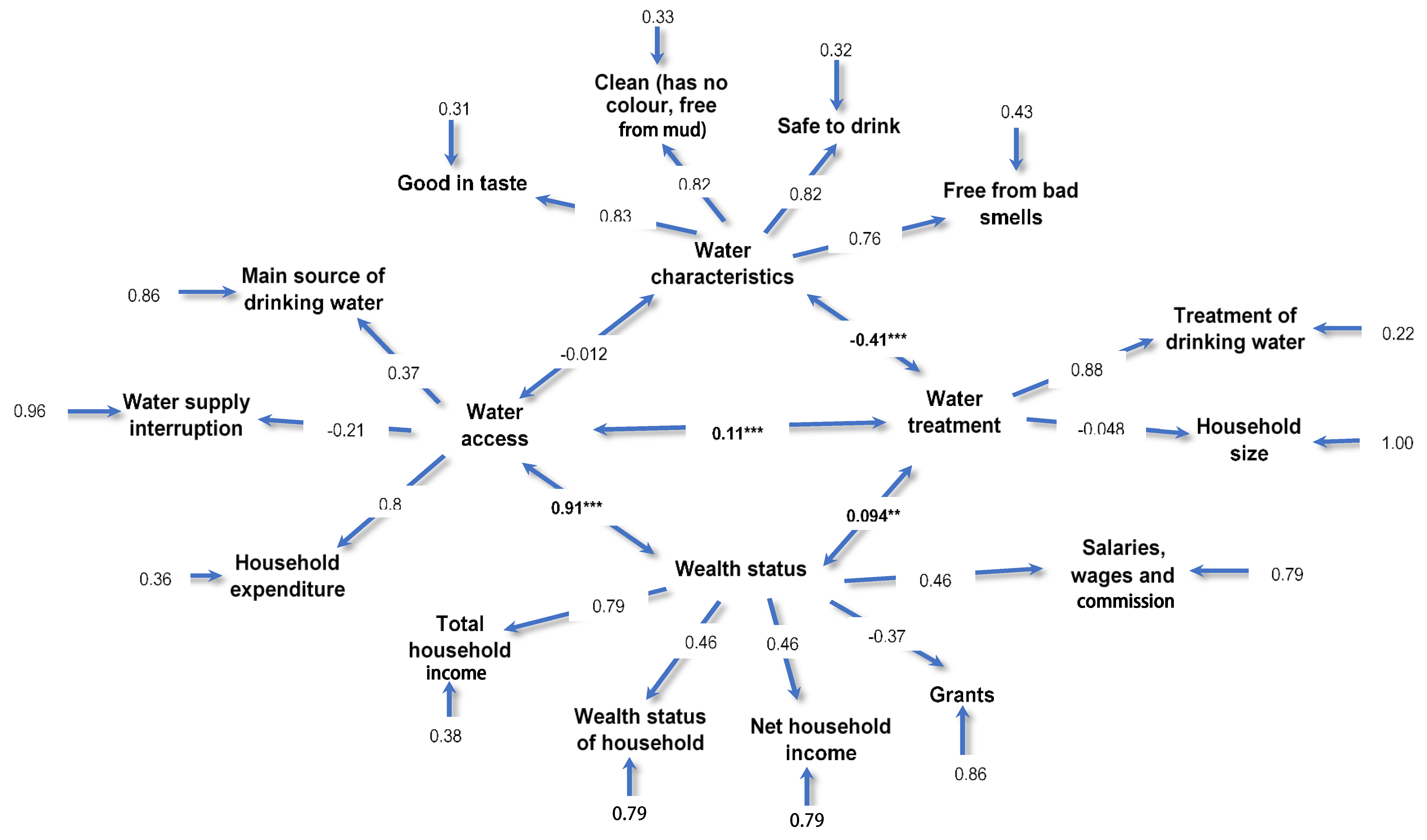

Gender equality and women empowerment is a key driver in ending hunger and poverty as well as improving water security. Women and girls are the primary providers, users and managers of water in the households [

6]. Women are vulnerable through exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacities to water insecurity. However, few studies have quantified the vulnerabilities and burdens of water insecurity on women. Most studies have utilised vulnerability assessments in climate change studies, through quantification of exposures, sensitivities and adaptive capacities. However, these have taken a linear form, neglecting the dynamism and pathways between these constructs of vulnerability. The objective of the study was to identify and provide pathways through which female-headed households were water insecure in South Africa. The study was innovative at two fronts: (i) adopting a vulnerability construct utilised in climate change studies and assessing water insecurity, and (ii) adopting a dynamic model showing pathways relative to a linear model which is typical of vulnerability assessments. This was established through non-convectional vulnerability measures looking at dynamic relationships between the constructs. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) as well as Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was utilised to provide the pathways through which 5928 female-headed households were water insecure. The PCA results indicated that:

- (a)

water characteristics, water access and household head age were the extracted factors for exposures to water insecurity;

- (b)

assets, monthly income and water treatment were the extracted factors for water insecurity sensitivities; and

- (c)

income and wealth status, salary and emittances, pensions, business as well as farm income were the extracted factors in the water insecurity adaptive capacity.

The PSM identified significant interrelationships in water insecurity from four attributes, namely the water characteristics, water access, water treatment and the wealth status of the female headed households. These describe various degrees of exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity to water insecurity. The study concludes that there are various dynamic intricacies between exposures, sensitivity and adaptive capacity to water insecurity for female headed households in South Africa (

Figure 7).

The study fits into the country’s water policy such as the National Water and Sanitation Master Plan (NWSMP) as well as the National Water Resource Strategy (NWRS2), especially in a decade of equity and redistribution [

19,

57,

58]. This is in recognition that there has been little substantive progress in the National Water Act on equity towards redressing gender water allocation [

19]. The NWRS2 has objectives of sustainable and equitable water use, development, conservation, management and control. Equity and redistribution will be achieved through water allocation reform as well as support for local economic development initiatives. This will focus on equity in access to water services, resources and benefits to make sure water is available to previously disadvantaged groups [

19]. The NWSMP recognises that water will become expensive, with everyone having to utilise less water as well as pay for the water [

24]. This will call into question the capabilities of discriminated groups such as women. The current study provides a reference point for the inclusion of women in the equity and redistribution agenda. In terms of practical option for solutions, policy makers are encouraged to be gender sensitive especially in the NWSMP and NWRS2, which tend to provoke equity discourse by rarely offers practical solutions or strategies.

The study identifies that in tackling water insecurity for female headed households in South Africa, a multi-prong approach is required looking at the exposures, sensitivities and adaptive capacities. Empowerment and poverty reduction amongst women will improve their adaptive capacity to water insecurity. This would require policy that increase women participation in the mainstream economy such that they improve their livelihoods through increasing their income generating abilities. Access to water treatment equipment will reduce the sensitivity of female headed households to water insecurity. In reducing the exposures to water insecurity, policy makers should prioritise improving infrastructure that delivers piped water into each household. This study follows a quantitative research approach, and it provided a limitation. However, water insecurity/scarcity/conservation is highly personal as well as context specific. Qualitative data could potentially add richness to the findings.