Avoiding the Use of Exhausted Drinking Water Filters: A Filter-Clock Based on Rusting Iron

Abstract

:1. Introduction

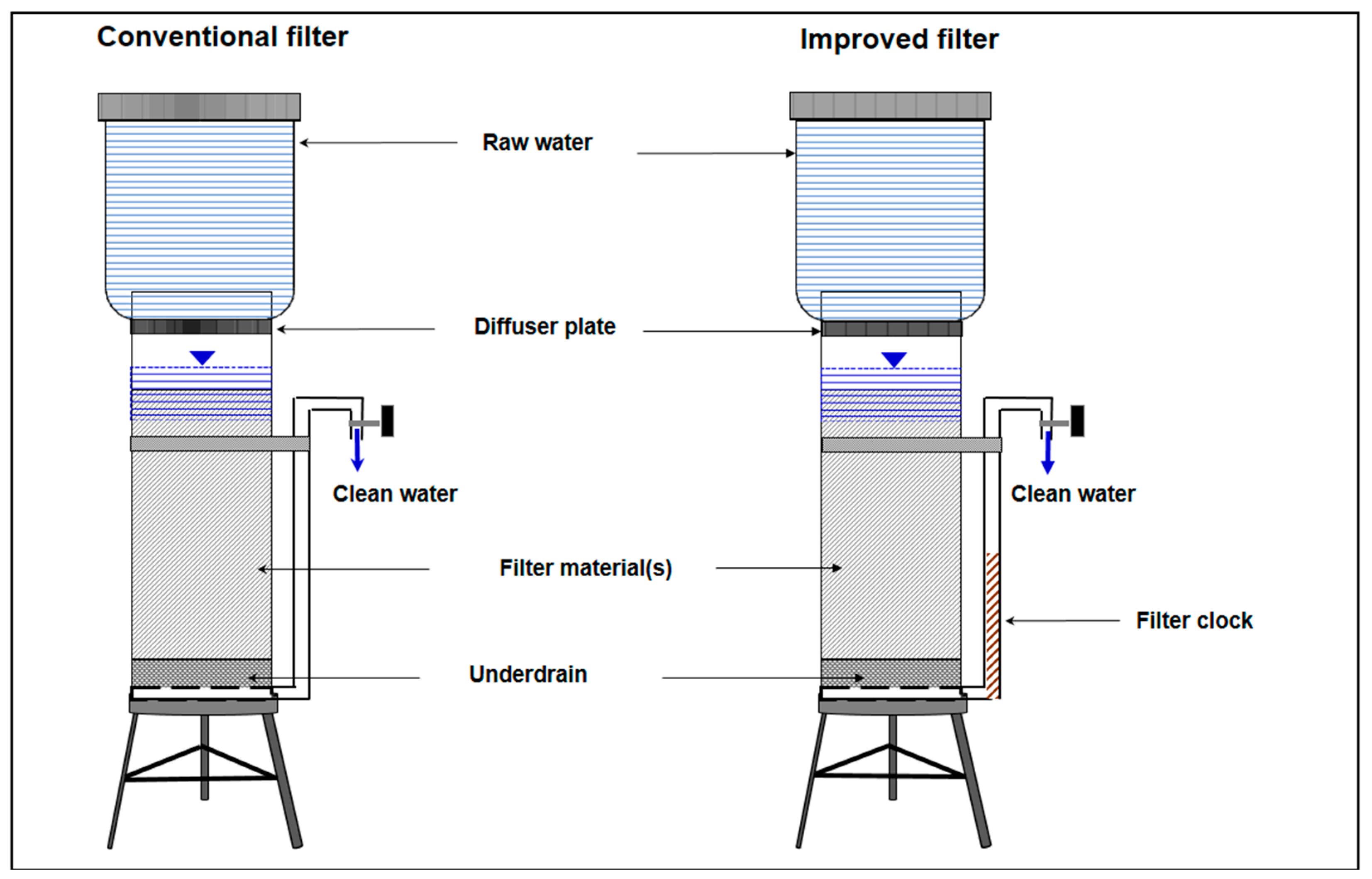

2. Commercial Household Water Filters: Now and Then

3. Fe0-Based Filter Clocks

3.1. General Aspects

3.2. Design Aspects

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shannon, M.A.; Bohn, P.W.; Elimelech, M.; Georgiadis, J.G.; Marinas, B.J.; Mayes, A.M. Science and technology for water purification in the coming decades. Nature 2008, 452, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, I. New generation adsorbents for water treatment. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5073–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chankova, S.; Hatt, L.; Musange, S. A community-based approach to promote household water treatment in Rwanda. J. Water Health 2012, 10, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, K.J.; Hand, D.W.; Crittenden, J.C.; Trussell, R.R.; Tchobanoglous, G. Principles of Water Treatment; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; p. 674. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.I. Alternatives for safe water provision in urban and peri-urban slums. J. Water Health 2010, 8, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseri, E.; Ndé-Tchoupé, A.I.; Mwakabona, H.T.; Nanseu-Njiki, C.P.; Noubactep, C.; Njau, K.N.; Wydra, K.D. Making Fe0-based filters a universal solution for safe drinking water provision. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I. The quest for active carbon adsorbent substitutes: Inexpensive adsorbents for toxic metal ions removal from wastewater. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2010, 39, 95–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Khan, T.A. Low cost adsorbents for removal of organic pollutants from wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 113, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, I. Water treatment by adsorption columns: Evaluation at ground level. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2014, 43, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, T.; Chaudhari, S. A cost-effective technology for arsenic removal: Case study of zerovalent iron-based IIT Bombay arsenic filter in West Bengal. In Water and Sanitation in the New Millennium; Nath, K., Sharma, V., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Makota, S.; Nde-Tchoupe, A.I.; Mwakabona, H.T.; Tepong-Tsindé, R.; Noubactep, C.; Nassi, A.; Njau, K.N. Metallic iron for water treatment: Leaving the valley of confusion. Appl. Water Sci. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubactep, C.; Temgoua, E.; Rahman, M.A. Designing iron-amended biosand filters for decentralized safe drinking water provision. Clean Soil Air Water 2012, 40, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caré, S.; Crane, R.; Calabrò, P.S.; Ghauch, A.; Temgoua, E.; Noubactep, C. Modelling the permeability loss of metallic iron water filtration systems. Clean Soil Air Water 2013, 41, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domga, R.; Togue-Kamga, F.; Noubactep, C.; Tchatchueng, J.B. Discussing porosity loss of Fe0 packed water filters at ground level. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 263, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Goldar, B.; Misra, S. Value of arsenic-free drinking water to rural households in Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 74, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndé-Tchoupé, A.I.; Crane, R.A.; Mwakabona, H.T.; Noubactep, C.; Njau, K.N. Technologies for decentralized fluoride removal: Testing metallic iron-based filters. Water 2015, 7, 6750–6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilling, N.B.; Bedworth, R.E. The oxidation of metals at high temperatures. J. Inst. Met. 1923, 29, 529–591. [Google Scholar]

- Caré, S.; Nguyen, Q.T.; L’Hostis, V.; Berthaud, Y. Mechanical properties of the rust layer induced by impressed current method in reinforced mortar. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, W.R. Water Supply, Considered Mainly from a Chemical and Sanitary Standpoint; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1883; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Devonshire, E. The purification of water by means of metallic iron. J. Frankl. Inst. 1890, 129, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakabona, H.T.; Ndé-Tchoupé, A.I.; Njau, K.N.; Noubactep, C.; Wydra, K.D. Metallic iron for safe drinking water provision: Considering a lost knowledge. Water Res. 2017, 117, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahi, E. Africa’s U-Turn in defluoridation policy: From the Nalgonda technique to bone char. Res. Rep. Fluoride 2016, 49 Pt 1, 401–416. [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale, R.A.; Emmons, A.H. A method for decontaminating small volumes of radioactive water. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 1951, 43, 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Gillham, R.W.; O’Hannesin, S.F. Enhanced degradation of halogenated aliphatics by zero-valent iron. Ground Water 1994, 32, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.D.; Demond, A.H. Long-term performance of zero-valent iron permeable reactive barriers: A critical review. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2007, 24, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheju, M. Hexavalent chromium reduction with zero-valent iron (ZVI) in aquatic systems. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011, 222, 103–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauch, A. Iron-based metallic systems: An excellent choice for sustainable water treatment. Freib. Online Geosci. 2015, 32, 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer, H.; Crittenden, J.C.; Summers, R.S. Activated Carbon for Water Treatment, 2nd ed.; DVGW-Forschungsstelle Karlsruhe: Karlsruhe, Germany, 1988; p. 722. [Google Scholar]

- Vidic, R.D.; Suidan, M.T.; Traegner, U.K.; Nakhla, G.F. Adsorption isotherms: Illusive capacity and role of oxygen. Water Res. 1990, 24, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi, W.; Chaukura, N.; Noubactep, C.; Mukome, F.N.D. Biochar-based water treatment systems as a potential low-cost and sustainable technology for clean water provision. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igalavithana, A.D.; Mandal, S.; Niazi, N.K.; Vithanage, M.; Parikh, S.J.; Mukome, F.N.D.; Rizwan, M.; Oleszczuk, P.; Al-Wabel, M.; Bolan, N.; et al. Advances and future directions of biochar characterization methods and applications. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tratneyk, P.G. Putting corrosion to use: Remediating contaminated groundwater with zero-valent metals. Chem. Ind. 1996, 13, 499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Fairweather, V. When toxics meet metal. Civ. Eng. 1996, 66, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gheju, M.; Balcu, I. Removal of chromium from Cr(VI) polluted wastewaters by reduction with scrap iron and subsequent precipitation of resulted cations. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 196, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, A.D.; Demond, A.H. Impact of solids formation and gas production on the permeability of ZVI PRBs. J. Environ. Eng. 2011, 137, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antia, D.D.J. Desalination of water using ZVI, Fe0. Water 2015, 7, 3671–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubactep, C. Metallic iron for environmental remediation: A review of reviews. Water Res. 2015, 85, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatcha-Bandjun, N.; Noubactep, C.; Loura Mbenguela, B. Mitigation of contamination in effluents by metallic iron: The role of iron corrosion products. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2017, 8, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndé-Tchoupé, A.I.; Makota, S.; Nassi, A.; Hu, R.; Noubactep, C. The Suitability of Pozzolan as Admixing Aggregate for Fe0-Based Filters. Water 2018, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enthaler, S.; Junge, K.; Beller, M. Sustainable metal catalysis with iron: From rust to a rising star? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3317–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraci, N.; Lelo, D.; Bilardi, S.; Calabrò, P.S. Modelling long-term hydraulic conductivity behaviour of zero valent iron column tests for permeable reactive barrier design. Can. Geotech. J. 2016, 53, 946–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubactep, C. Designing metallic iron packed-beds for water treatment: A critical review. Clean Soil Air Water 2016, 44, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubactep, C. No scientific debate in the zero-valent iron literature. Clean Soil Air Water 2016, 44, 330–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubactep, C. Research on metallic iron for environmental remediation: Stopping growing sloppy science. Chemosphere 2016, 153, 528–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noubactep, C. Predicting the hydraulic conductivity of metallic iron filters: Modeling gone astray. Water 2016, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhoff, P.; James, J. Nitrate removal in zero-valent iron packed columns. Water Res. 2003, 37, 1818–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comba, S.; Di Molfetta, A.; Sethi, R. A Comparison between field applications of nano-, micro-, and millimetric zero-valent iron for the remediation of contaminated aquifers. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011, 215, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacławek, S.; Nosek, J.; Cádrová, L.; Antoš, V.; Černík, M. Use of various zero valent irons for degradation of chlorinated ethenes and ethanes. Ecol. Chem. Eng. 2015, S22, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubactep, C.; Makota, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Rescuing Fe0 remediation research from its systemic flaws. Res. Rev. Insights 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubactep, C. Metallic iron (Fe0) provide possible solution to universal safe drinking water provision. J. Water Technol. Treat. Methods 2018, 1, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndé-Tchoupé, A.I. Conception et Dimensionnement des Filtres à fer méTallique Pour Emploi Domestique. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Douala, Douala, Cameroon, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ndé-Tchoupé, A.I.; Lufingo, M.; Hu, R.; Gwenzi, W.; Ntwampe, S.K.O.; Noubactep, C.; Njau, K.N. Avoiding the Use of Exhausted Drinking Water Filters: A Filter-Clock Based on Rusting Iron. Water 2018, 10, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10050591

Ndé-Tchoupé AI, Lufingo M, Hu R, Gwenzi W, Ntwampe SKO, Noubactep C, Njau KN. Avoiding the Use of Exhausted Drinking Water Filters: A Filter-Clock Based on Rusting Iron. Water. 2018; 10(5):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10050591

Chicago/Turabian StyleNdé-Tchoupé, Arnaud Igor, Mesia Lufingo, Rui Hu, Willis Gwenzi, Seteno Karabo Obed Ntwampe, Chicgoua Noubactep, and Karoli N. Njau. 2018. "Avoiding the Use of Exhausted Drinking Water Filters: A Filter-Clock Based on Rusting Iron" Water 10, no. 5: 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10050591

APA StyleNdé-Tchoupé, A. I., Lufingo, M., Hu, R., Gwenzi, W., Ntwampe, S. K. O., Noubactep, C., & Njau, K. N. (2018). Avoiding the Use of Exhausted Drinking Water Filters: A Filter-Clock Based on Rusting Iron. Water, 10(5), 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10050591