Public Awareness of Drinking Water Safety and Contamination Accidents: A Case Study in Hainan Province, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Information of Respondents

3.2. Public Awareness about Drinking Water Safety

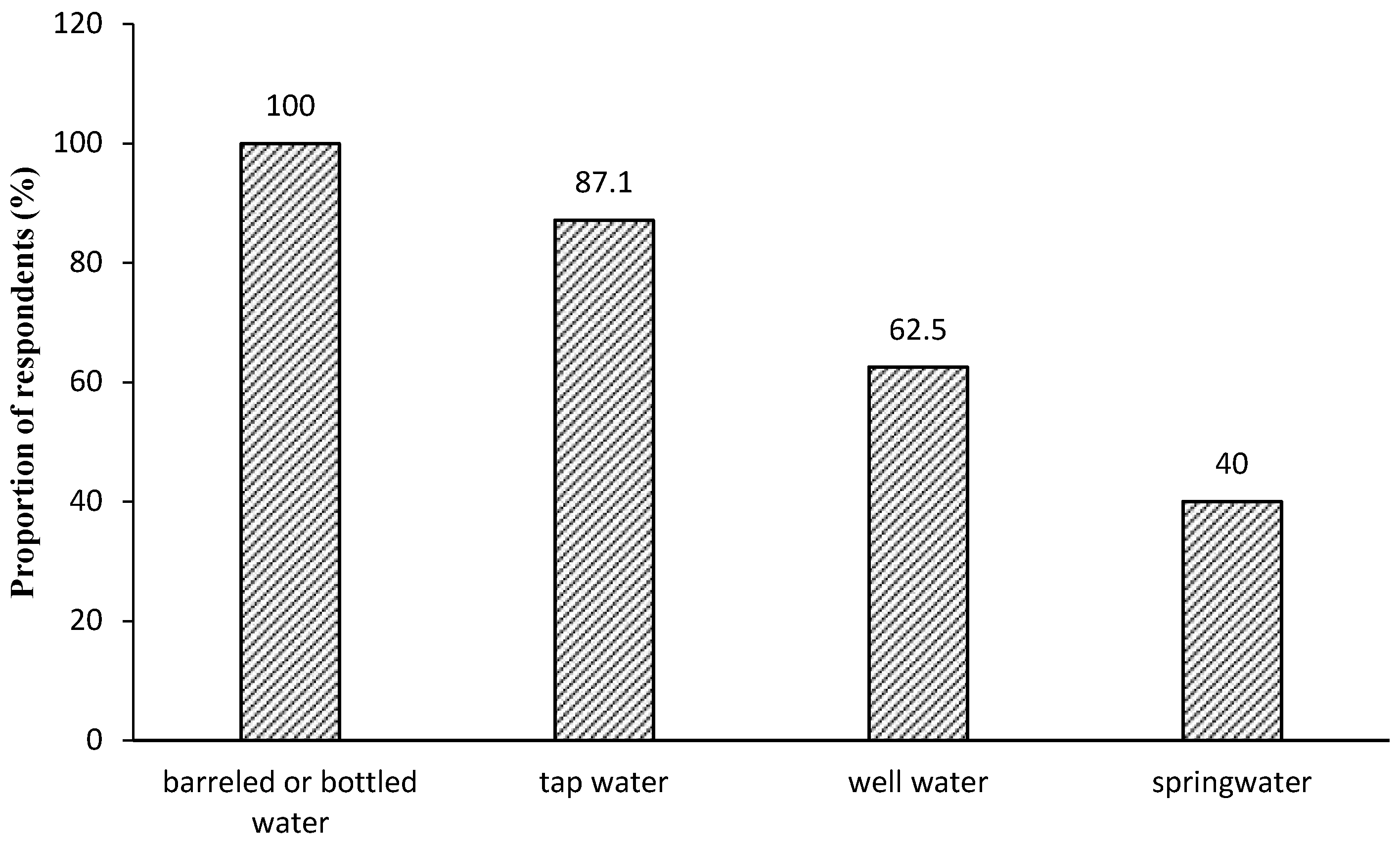

3.2.1. Household Drinking Water Sources

3.2.2. Public Attention of Local Drinking Water Quality

3.2.3. Public Satisfaction with Drinking Water Quality

3.2.4. Public Trust in the Safety of Drinking Water

3.2.5. Public Awareness of Tap Water Common Problems and Solutions

3.3. Public Awareness about Water Contamination Accidents

3.3.1. Public Awareness about Water Pollution Events

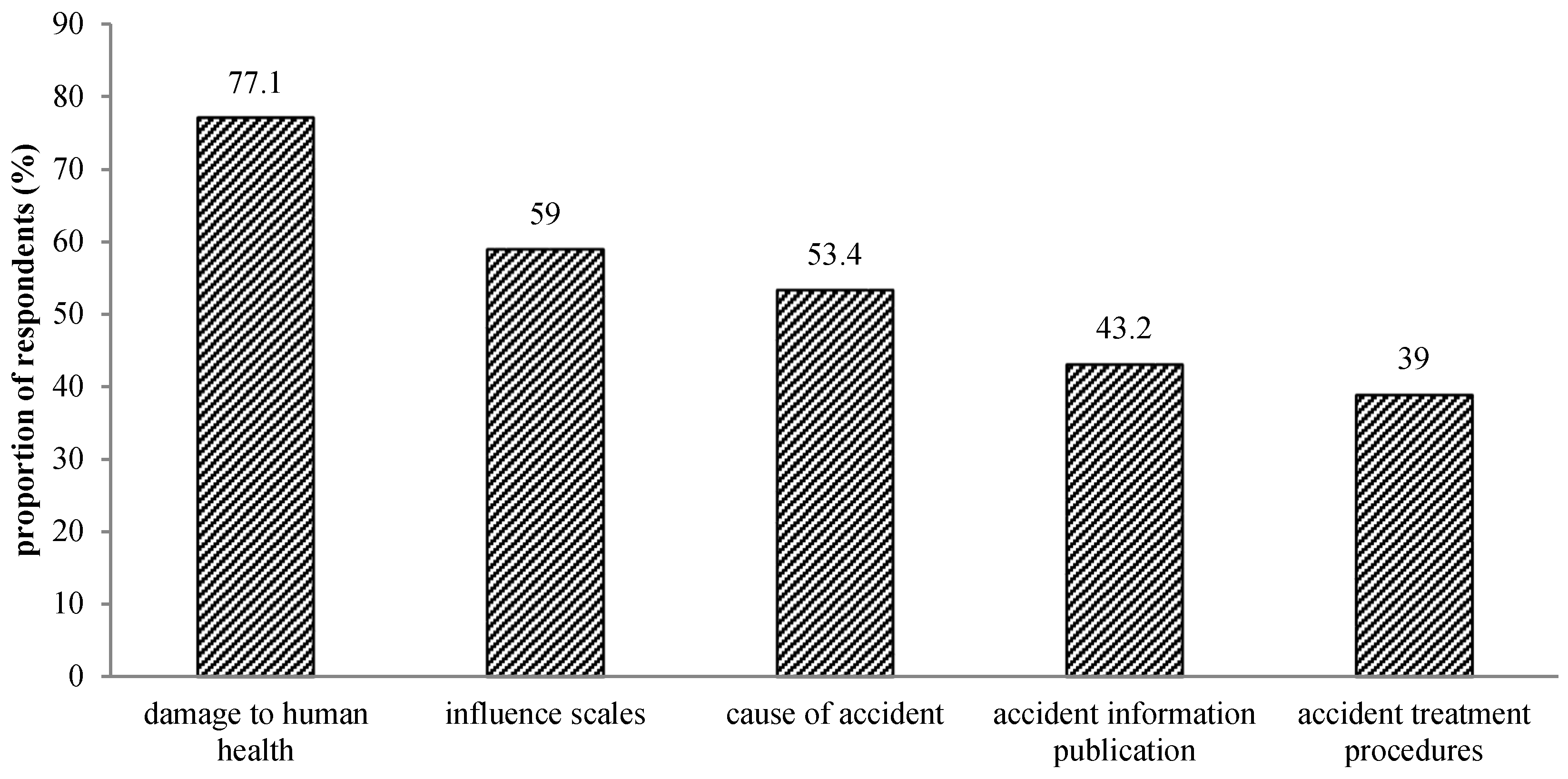

3.3.2. Public Knowledge about Water Pollution Accidents

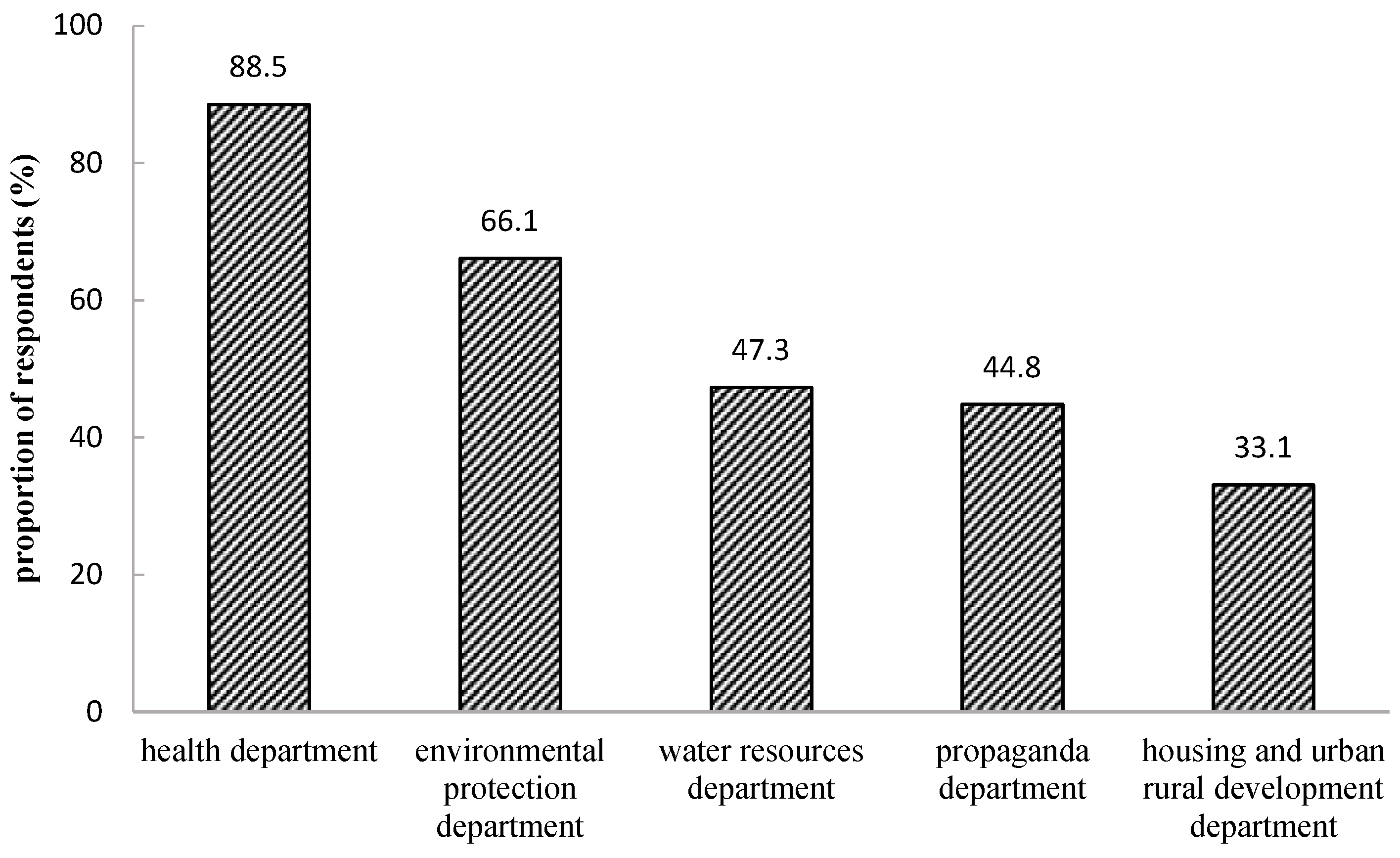

3.3.3. Measures Taken for Preventing Water Pollution Accidents

3.4. Comparison between Ding’an County and Ledong County

3.5. Influencing Factors of Public Awareness about Drinking Water Safety and Pollution Accidents

3.5.1. Influencing Factors of Public Satisfaction with Drinking Water Safety

3.5.2. Influencing Factors of Public Awareness about Drinking Water Pollution Accidents

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.J.; Chen, C.; Lin, P.F.; Hou, A.X.; Niu, Z.B.; Wang, J. Emergency drinking water treatment during source water pollution accidents in China: Origin analysis, framework and technologies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleick, P.H.; Cohen, M.J. The World’s Water 2008-2009: The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Xu, J.P.; Luo, H.W. An integrated approach to modelling the Economy-Society-Ecology system in urbanization process. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1946–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Sun, M.X.; Yang, X.C.; Yuan, X.L. Public awareness and willingness to pay for tackling smog pollution in China: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria, M. Factors influencing public perception of drinking water quality. Water Policy 2010, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Water Association (IWA). The Bonn Charter for Safe Drinking Water; IWA: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mahler, R.L.; Barber, M.E.; Shafii, B. Urban public satisfaction with drinking water since 2002 in the Pacific northwest, USA. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2015, 10, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, E.G. Drinking water quality in the new millennium: The risk of underestimating public perception. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 2002, 94, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mihaly, M. Citizen participation in the making of environmental decisions: Evolving obstacles and potential solutions through partnership with experts and agents. Pace Environ. Law Rev. 2009, 27, 151–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hoedjes, J.C.B. Public Participation in Environmental Research; Occasional Paper 22; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.M.; Wen, P. Review on environmental policies in China: Evolvement, features, and evaluation. Environ. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. China 2008, 2, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.H.; Tseng, Y.H.; Chen, C.P. Environmental regulations, induced R&D, and productivity: Evidence from Taiwan’s manufacturing industries. Resour. Energy Econ. 2012, 34, 514–532. [Google Scholar]

- European Economic Area (EEA). Public Participation: Contributing to Better Water Management Experiences from Eight Case Studies across Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J.A.; Yang, H.; Rivett, U.; Gundrg, S.W. Public perception of drinking water safety in South Africa 2002–2009: A repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calicioglu, O.; Hepgunes, E.; Firat, Μ.; Alp, E. Public perception and willingness to pay analysis for the improved water quality in Ankara, Turkey. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, Rhodes, Greece, 8–10 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fröhler, M.; Elmadfa, I. Public perception of drinking water quality in Austria. Nutrition 2010, 34, 206–214. [Google Scholar]

- Doria, M.D.; Pidgeon, N.; Hunter, P.R. Perceptions of drinking water quality and risk and its effect on behaviour: A cross-national study. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 5455–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgeon, S.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Theriault, M.; Levallois, P. Perception of drinking water in the Quebec City region (Canada): The influence of water quality and consumer location in the distribution system. J. Environ. Manag. 2004, 70, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, M.W.; Talkhande, A.V.; Andey, S.P.; Kelkar, P.S. Urban community perception towards intermittent water supply system. Indian J. Environ. Health 2002, 44, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. Available online: http://www.unicef.org/wash/index_watersecurity.html (accessed on 7 November 2017).

- Van Der Linden, S. Exploring beliefs about bottled water and intentions to reduce consumption: The dual-effect of social norm activation and persuasive information. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 526–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, T.K.; Tae, S.K. Analysis of brand naming and marketing implications of mineral water sold in China: Jeju SamDaSoo, Evian, and Tibet Spring 5100. J. Hum. Stud. 2015, 36, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- 2016 Hainan Environmental Status Bulletin. Available online: http://hi.people.com.cn/n2/2017/0605/c231190-30278269.html (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Brikké, F.; Bredero, M. Linking Technology Choice with Operation and Maintenance in the Context of Community Water Supply and Sanitation: A Reference Document for Planners and Project Staff; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre: Hague, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Water Safety Planning for Small Community Water Supplies: Step-by-Step Risk Management Guidance for Drinking-Water Supplies in Small Communities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, T.; Xin, K.; Xia, Y.; Liu, S. A risk assessment of the tap drinking water quality in a water distribution system based on consumer complaints. Water Distrib. Syst. Anal. 2011, 2010, 595–603. [Google Scholar]

- Atputharaj, A.U.E. The Influence of Service Quality Factors on Customer Satisfaction and Drinking Water Quality in Syarikat Bekalan Air Selangor (SYABAS). Master’s Thesis, University Utara Malaysia, Changlun, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, D.P. Tapping into consumer perceptions of drinking water quality in Canada: Capturing consumer demand to assist in better management of water resources. Can. Water Resour. J. 2005, 30, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Consumer Confidence Reports: Building Public Trust; National Primary Drinking Water Standards; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Johnson, B.B. Do reports on drinking water affect customers’ concerns? Experiments in report content. Risk Anal. 2003, 23, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hainan from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hainan (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Lu, W.Q.; Xie, S.H.; Zhou, W.S.; Zhang, S.H.; Liu, A.L. Water pollution and health impact in China: A mini review. Open Environ. Sci. 2008, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Spatial-Temporal analysis of heavy metal water pollution and the impact on public health in China. J. Plant Res. 2015, 116, 455–460. [Google Scholar]

- Hainan Province Environmental Information Public Publishing System. Available online: http://wr.hnsthb.gov.cn/wry/ (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- The World Bank. Water Pollution Emergencies in China: Prevention and Response; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Wang, X.L.; Li, K.Q.; Liang, S.; Qian, G.D.; Jin, H.; Dai, A.Q. Estimation methods and monitoring network issues in the quantitative estimation of land-based COD and TN loads entering the sea: A case study in Qingdao City, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 10067–10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistical Bureau of Hainan Province. Hainan Statistical Yearbook 2017; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Eilam, E.; Trop, T. Factors influencing adults’ environmental attitudes and behaviors and the role of environmental schools in influencing their communities. Educ. Urban Soc. 2014, 46, 234–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaim, J.; Maloni, M.; Napshin, S.; Henley, A. Influences on student intention and behavior toward environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | The main questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | What kind of water do you use as the main source of your drinking water? |

| 2 | Do you pay attention to local drinking water quality? |

| 3 | Are you satisfied with your drinking water quality? |

| 4 | Do you trust the safety of your drinking water? |

| 5 | Do you have any problems with your tap water quality? |

| 6 | When you have problems with your drinking water (such as water quality abnormal, pipeline damage, faucet water leakage, etc.), how do you solve these problems? |

| 7 | What factors can affect the quality of tap water? |

| 8 | Do you pay attention to the water pollution events reported on TV or in the newspaper? |

| 9 | What kind of water pollution events do you pay attention to? |

| 10 | What information do you mainly pay attention to the water pollution events? |

| 11 | Who do you think as the main emergency response provider during drinking water contamination accidents? |

| 12 | What do you think should be strengthened at the emergency disposal process? |

| 13 | What do you think should be done to reduce pollution emergencies? |

| Total | Ding’an County | Ledong County | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Age | ||||||

| >50 | 72 | 17.6% | 43 | 21.4% | 29 | 13.9% |

| 35–50 | 163 | 39.8% | 71 | 35.3% | 92 | 44.0% |

| 20–34 | 162 | 39.5% | 79 | 39.3% | 83 | 39.7% |

| <20 | 13 | 3.2% | 8 | 4.0% | 5 | 2.4% |

| Sex | ||||||

| male | 167 | 40.7% | 95 | 47.3% | 72 | 34.4% |

| female | 243 | 59.3% | 106 | 52.7% | 137 | 65.6% |

| Education level | ||||||

| bachelor and above | 74 | 18.0% | 46 | 22.9% | 28 | 13.4% |

| college | 112 | 27.3% | 48 | 23.9% | 64 | 30.6% |

| high school | 156 | 38.0% | 64 | 31.8% | 92 | 44.0% |

| middle school | 57 | 13.9% | 35 | 17.4% | 22 | 10.5% |

| primary school and below | 11 | 2.7% | 8 | 4.0% | 3 | 1.4% |

| Total | Ding’an County | Ledong County | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Sources of household drinking water | ||||||

| tap water | 313 | 70.7% | 175 | 80.3% | 138 | 61.3% |

| barreled or bottled water | 23 | 5.2% | 7 | 3.2% | 16 | 7.1% |

| well water | 101 | 22.8% | 33 | 15.1% | 68 | 30.2% |

| spring water | 5 | 1.1% | 3 | 1.4% | 2 | 0.9% |

| others | 1 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.4% |

| Public attention of local water quality | ||||||

| special attention | 93 | 22.7% | 35 | 17.4% | 58 | 27.8% |

| comparatively high attention | 230 | 56.1% | 117 | 58.2% | 113 | 54.1% |

| no concerned | 67 | 16.3% | 44 | 21.9% | 23 | 11.0% |

| no answer | 20 | 4.9% | 5 | 2.5% | 15 | 7.2% |

| The degree of public satisfaction with drinking water quality | ||||||

| very satisfied | 84 | 20.5% | 71 | 35.3% | 13 | 6.2% |

| relatively satisfied | 245 | 59.8% | 109 | 54.2% | 136 | 65.1% |

| dissatisfied | 75 | 18.3% | 21 | 10.4% | 54 | 25.8% |

| no answer | 6 | 1.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 2.9% |

| The degree of public trust in the safety of drinking water | ||||||

| confident | 70 | 17.1% | 64 | 31.8% | 6 | 2.9% |

| relatively confident | 173 | 42.2% | 85 | 42.3% | 88 | 42.1% |

| somewhat worried | 143 | 34.9% | 43 | 21.4% | 100 | 47.8% |

| extremely worried | 21 | 5.1% | 8 | 4.0% | 13 | 6.2% |

| no answer | 3 | 0.7% | 1 | 0.5% | 2 | 1.0% |

| Public awareness of problems with their tap water | ||||||

| never had problems | 258 | 62.9% | 155 | 77.1% | 103 | 49.3% |

| had problems once or twice a year | 106 | 25.9% | 34 | 16.9% | 72 | 34.4% |

| had problems frequently | 18 | 4.4% | 8 | 4.0% | 10 | 4.8% |

| no answer | 28 | 6.8% | 4 | 2.0% | 24 | 11.5% |

| The measures taken to solve problems that arise with tap water | ||||||

| solve problems by themselves | 206 | 52.4% | 108 | 37.8% | 98 | 39.7% |

| help by local water utility | 68 | 17.3% | 35 | 12.2% | 33 | 13.4% |

| complain to the local department of health | 166 | 42.2% | 87 | 30.4% | 79 | 32.0% |

| help by the residential property maintenance staff | 86 | 21.9% | 52 | 18.2% | 34 | 13.8% |

| call the local government telephone hotline for help | 7 | 1.8% | 4 | 1.4% | 3 | 1.2% |

| Degree of Public Satisfaction with Drinking Water Quality a | B | Std. Error | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% Confidence Interval for Exp (B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||||

| very satisfied | intercept | −0.939 | 1.544 | 0.370 | 1 | 0.543 | |||

| >50 | −0.194 | 0.994 | 0.038 | 1 | 0.846 | 0.824 | 0.117 | 5.783 | |

| 35–50 | 0.755 | 0.946 | 0.637 | 1 | 0.425 | 2.128 | 0.333 | 13.603 | |

| 20–34 | −0.301 | 0.952 | 0.100 | 1 | 0.752 | 0.740 | 0.115 | 4.781 | |

| <20 | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| male | 0.349 | 0.391 | 0.798 | 1 | 0.372 | 1.418 | 0.659 | 3.048 | |

| female | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| bachelor and above | 0.141 | 1.327 | 0.011 | 1 | 0.915 | 1.151 | 0.085 | 15.507 | |

| college | −0.754 | 1.266 | 0.354 | 1 | 0.552 | 0.471 | 0.039 | 5.625 | |

| high school | −1.018 | 1.236 | 0.678 | 1 | 0.410 | 0.361 | 0.032 | 4.074 | |

| middle school | −0.965 | 1.264 | 0.584 | 1 | 0.445 | 0.381 | 0.032 | 4.533 | |

| primary school and below | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| within CDWQHMN | 2.627 | 0.413 | 40.552 | 1 | 0.000 | 13.833 | 6.163 | 31.051 | |

| outside of CDWQHMN | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| satisfied | intercept | 0.908 | 1.350 | 0.452 | 1 | 0.501 | |||

| >50 | 0.121 | 0.784 | 0.024 | 1 | 0.877 | 1.129 | 0.243 | 5.248 | |

| 35–50 | 0.278 | 0.748 | 0.138 | 1 | 0.710 | 1.321 | 0.305 | 5.723 | |

| 20–34 | −0.199 | 0.741 | 0.072 | 1 | 0.788 | 0.819 | 0.192 | 3.500 | |

| <20 | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| male | 0.334 | 0.315 | 1.130 | 1 | 0.288 | 1.397 | 0.754 | 2.588 | |

| female | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| bachelor and above | 0.943 | 1.235 | 0.583 | 1 | 0.445 | 2.568 | 0.228 | 28.915 | |

| college | 0.086 | 1.172 | 0.005 | 1 | 0.941 | 1.090 | 0.110 | 10.830 | |

| high school | −0.420 | 1.152 | 0.133 | 1 | 0.715 | 0.657 | 0.069 | 6.277 | |

| middle school | −0.480 | 1.170 | 0.169 | 1 | 0.681 | 0.619 | 0.062 | 6.123 | |

| primary school and below | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| within CDWQHMN | 0.633 | 0.302 | 4.380 | 1 | 0.036 | 1.883 | 1.041 | 3.405 | |

| outside of CDWQHMN | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| Public Attention to Local Water Quality a | B | Std. Error | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% Confidence Interval for Exp (B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||||

| extremely concerned | intercept | −0.125 | 1.237 | 0.010 | 1 | 0.920 | |||

| >50 | −0.210 | 0.921 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.819 | 0.810 | 0.133 | 4.930 | |

| 35–50 | −0.590 | 0.871 | 0.459 | 1 | 0.498 | 0.554 | 0.101 | 3.057 | |

| 20–34 | −1.009 | 0.880 | 1.314 | 1 | 0.252 | 0.365 | 0.065 | 2.047 | |

| <20 | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| male | 0.543 | 0.382 | 2.020 | 1 | 0.155 | 1.720 | 0.814 | 3.636 | |

| female | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| bachelor and above | 2.772 | 1.007 | 7.585 | 1 | 0.006 | 15.993 | 2.224 | 115.005 | |

| college | 1.511 | 0.963 | 2.462 | 1 | 0.117 | 4.531 | 0.686 | 29.914 | |

| high school | 1.602 | 0.927 | 2.983 | 1 | 0.084 | 4.961 | 0.806 | 30.539 | |

| middle school | 0.985 | 0.952 | 1.070 | 1 | 0.301 | 2.679 | 0.414 | 17.327 | |

| primary school and below | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| within CDWQHMN | −1.326 | 0.361 | 13.477 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.266 | 0.131 | 0.539 | |

| outside of CDWQHMN | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| fairly concerned | intercept | −0.620 | 1.093 | 0.321 | 1 | 0.571 | |||

| >50 | 0.304 | 0.836 | 0.132 | 1 | 0.716 | 1.355 | 0.263 | 6.979 | |

| 35–50 | −0.014 | 0.790 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.209 | 4.643 | |

| 20–34 | −0.224 | 0.795 | 0.079 | 1 | 0.778 | 0.799 | 0.168 | 3.800 | |

| <20 | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| male | 0.406 | 0.333 | 1.489 | 1 | 0.222 | 1.501 | 0.782 | 2.884 | |

| female | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| bachelor and above | 2.779 | 0.873 | 10.144 | 1 | 0.001 | 16.108 | 2.912 | 89.091 | |

| college | 2.460 | 0.815 | 9.117 | 1 | 0.003 | 11.709 | 2.371 | 57.824 | |

| high school | 2.192 | 0.790 | 7.703 | 1 | 0.006 | 8.950 | 1.904 | 42.075 | |

| middle school | 1.342 | 0.806 | 2.772 | 1 | 0.096 | 3.825 | 0.788 | 18.558 | |

| primary school and below | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| within CDWQHMN | −0.623 | 0.310 | 4.050 | 1 | 0.044 | 0.536 | 0.292 | 0.984 | |

| outside of CDWQHMN | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| Public Awareness of Water Pollution Accidents a | B | Std. Error | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% Confidence Interval for Exp (B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||||

| extremely concerned | intercept | −1.092 | 1.229 | 0.789 | 1 | 0.374 | |||

| >50 | 0.285 | 0.926 | 0.095 | 1 | 0.758 | 1.330 | 0.216 | 8.171 | |

| 35–50 | −0.310 | 0.847 | 0.134 | 1 | 0.714 | 0.733 | 0.139 | 3.860 | |

| 20–34 | −0.324 | 0.860 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.706 | 0.723 | 0.134 | 3.901 | |

| <20 | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| male | 0.791 | 0.378 | 4.370 | 1 | 0.037 | 2.206 | 1.051 | 4.630 | |

| female | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| bachelor and above | 2.959 | 1.032 | 8.214 | 1 | 0.004 | 19.272 | 2.548 | 145.768 | |

| college | 2.696 | 0.963 | 7.840 | 1 | 0.005 | 14.815 | 2.245 | 97.773 | |

| high school | 2.107 | 0.928 | 5.156 | 1 | 0.023 | 8.223 | 1.334 | 50.681 | |

| middle school | 1.502 | 0.942 | 2.543 | 1 | 0.111 | 4.490 | 0.709 | 28.432 | |

| primary school and below | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| within CDWQHMN | −0.739 | 0.340 | 4.733 | 1 | 0.030 | 0.477 | 0.245 | 0.929 | |

| outside of CDWQHMN | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| fairly concerned | intercept | −1.103 | 1.113 | 0.982 | 1 | 0.322 | |||

| >50 | 0.888 | 0.860 | 1.067 | 1 | 0.302 | 2.430 | 0.451 | 13.101 | |

| 35–50 | −0.193 | 0.786 | 0.060 | 1 | 0.806 | 0.825 | 0.177 | 3.851 | |

| 20–34 | −0.091 | 0.797 | 0.013 | 1 | 0.909 | 0.913 | 0.192 | 4.351 | |

| <20 | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| male | 0.326 | 0.360 | 0.820 | 1 | 0.365 | 1.385 | 0.684 | 2.806 | |

| female | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| bachelor and above | 3.467 | 0.930 | 13.883 | 1 | 0.000 | 32.034 | 5.172 | 198.432 | |

| college | 2.905 | 0.862 | 11.349 | 1 | 0.001 | 18.265 | 3.370 | 98.991 | |

| high school | 2.509 | 0.823 | 9.305 | 1 | 0.002 | 12.297 | 2.452 | 61.668 | |

| middle school | 1.623 | 0.830 | 3.819 | 1 | 0.051 | 5.068 | 0.995 | 25.805 | |

| primary school and below | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

| within CDWQHMN | −0.413 | 0.318 | 1.689 | 1 | 0.194 | 0.662 | 0.355 | 1.234 | |

| outside of CDWQHMN | 0.000 | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | . | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Lv, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, B. Public Awareness of Drinking Water Safety and Contamination Accidents: A Case Study in Hainan Province, China. Water 2018, 10, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10040446

Wang L, Zhang L, Lv J, Zhang Y, Ye B. Public Awareness of Drinking Water Safety and Contamination Accidents: A Case Study in Hainan Province, China. Water. 2018; 10(4):446. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10040446

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Li, Lan Zhang, Jia Lv, Yawei Zhang, and Bixiong Ye. 2018. "Public Awareness of Drinking Water Safety and Contamination Accidents: A Case Study in Hainan Province, China" Water 10, no. 4: 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10040446

APA StyleWang, L., Zhang, L., Lv, J., Zhang, Y., & Ye, B. (2018). Public Awareness of Drinking Water Safety and Contamination Accidents: A Case Study in Hainan Province, China. Water, 10(4), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10040446