Assessment of Water Quality in Roof-Harvested Rainwater Barrels in Greater Philadelphia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas and Survey

2.2. Barrel Water Sampling

2.3. Physico-Chemical Parameters

2.4. Heavy Metals

2.5. Enumeration of Fecal Indicator Bacteria (FIB)

2.6. DNA Extraction and Assessment of PCR Inhibition

2.7. Pathogen Quantification

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. 2014 Pilot on-Site Observations and Survey/Sanitary Survey Data for 2016 Rain Barrels

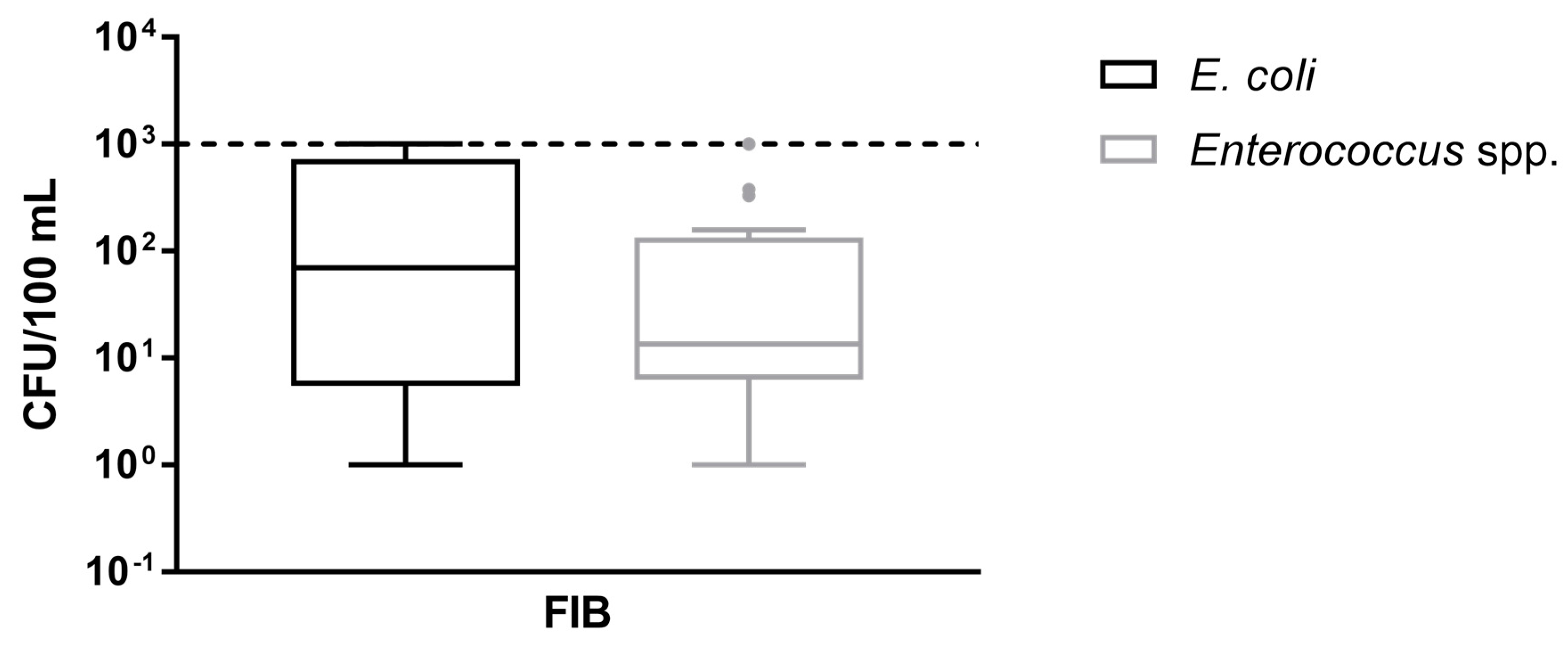

3.2. Physico-Chemical Parameters and Fecal Indicator Bacteria (FIB) from 2016 Samplings

3.3. Concentrations of Potential Opportunistic Pathogens in 2014 and 2016 Tank Water Samples

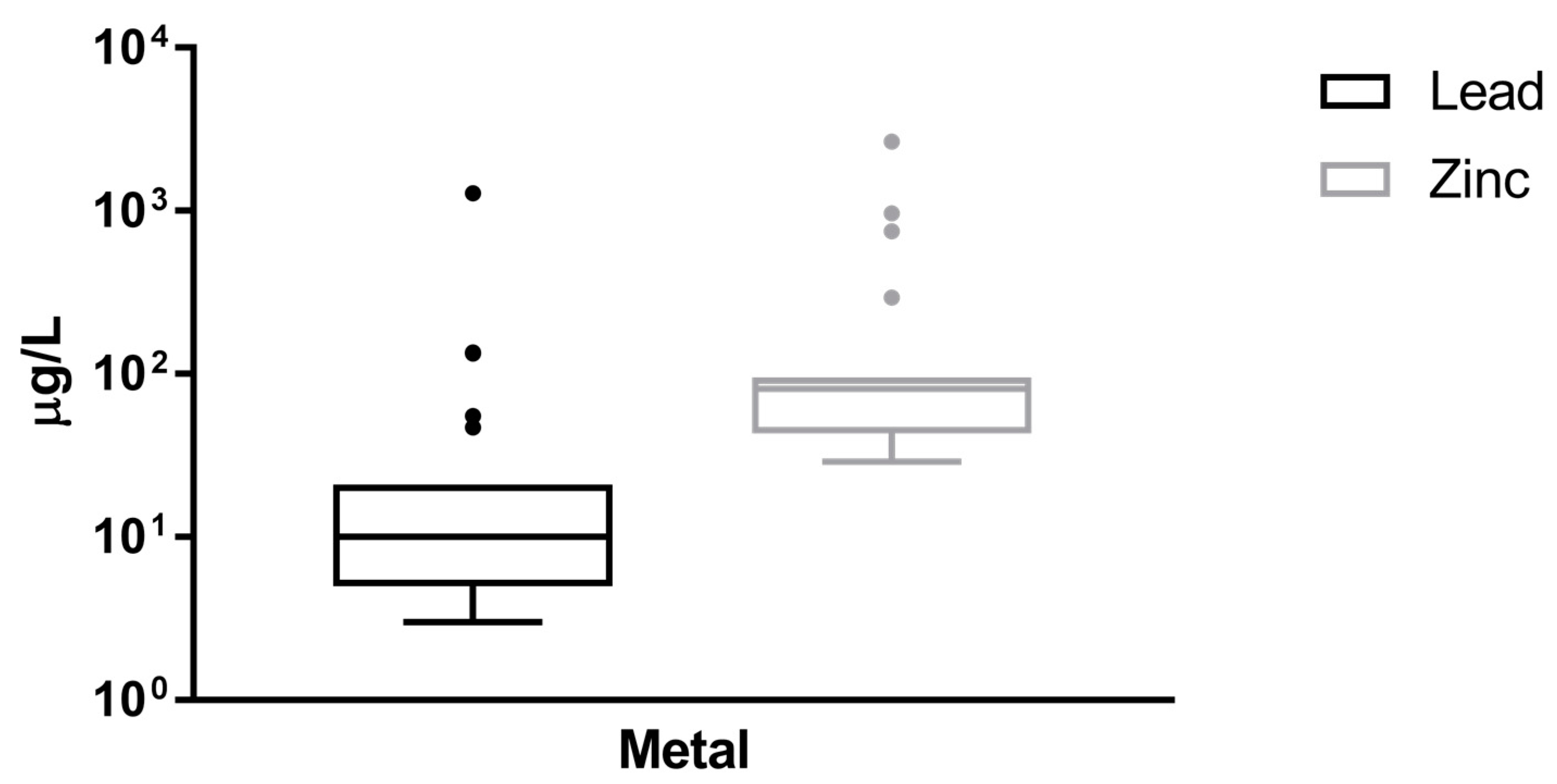

3.4. Lead and Zinc

3.5. Correlations among Contaminants, and between Contaminants and Physico-Chemical Parameters

3.6. Correlations between Contaminants, Meteorological, and Survey Parameters

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hanjra, M.A.; Blackwell, J.; Carr, G.; Zhang, F.; Jackson, T.M. Wastewater irrigation and environmental health: Implications for water governance and public policy. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2007, 215, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.B.; Kirisits, M.J.; Lye, D.J.; Kinney, K.A. Rainwater harvesting in the United States: A survey of common system practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 75, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philadelphia Water Department (PWD). Philadelphia Water Department Rain Check. 2017. Available online: http://www.phillywatersheds.org/whats_in_it_for_you/residents/raincheck/rain-barrel (accessed on 15 June 2016).

- Ahmed, W.; Hodgers, L.; Sidhu, J.P.S.; Toze, S. Fecal indicators and zoonotic pathogens in household drinking water taps fed from rainwater tanks in Southeast Queensland, Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrowsky, P.H.; De Kwaadsteniet, M.; Cloete, T.E.; Khan, W. Distribution of indigenous bacterial pathogens and potential pathogens associated with roof-harvested rainwater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.A.; Ahmed, W.; Palmer, A.; Sidhu, J.P.S.; Hodgers, L.; Toze, S.; Haas, C.N. Public health implications of Acanthamoeba and multiple potential opportunistic pathogens in roof-harvested rainwater tanks. Environ. Res. 2016, 150, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daoud, A.K.; Swaileh, K.M.; Hussein, R.M.; Matani, M. Quality assessment of roof-harvested rainwater in the West Bank, Palestinian Authority. J. Water Health 2011, 9, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uba, B.N.; Aghogho, O. Rainwater quality from different roof catchments in the Port Harcourt district, Rivers State, Nigeria. J. Water Supply Res. Technol. 2000, 49, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, F.; Köchling, T.; Luz, J.; Santos, S.M.; Gavazza, S. Water quality and microbial diversity in cisterns from semiarid areas in Brazil. J. Water Health 2014, 12, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Despins, C.; Farahbakhsh, K.; Leidl, C. Assessment of rainwater quality from rainwater harvesting systems in Ontario, Canada. J. Water Supply Res. Technol. 2009, 58, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Sidhu, J.P.S.; Toze, S. An attempt to identify the likely sources of Escherichia coli harboring toxin genes in rainwater tanks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 5193–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilvers, B.L.; Cowan, P.E.; Waddington, D.C.; Kelly, P.J.; Brown, T.J. The prevalence of infection of Giardia spp. and Cryptosporidium spp. in wild animals on farmland, southeastern North Island, New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 1998, 8, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.A.; Ahmed, W.; Palmer, A.; Smith, K.; Toze, S.; Haas, C.N. A seasonal assessment of opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens in roof-harvested rainwater tanks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 1742–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, E.D.; Iseman, M.D. Underlying host risk factors for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. In Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine; Thieme Medical Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 110–123. [Google Scholar]

- Falkinham, J.O., III. Ecology of nontuberculous Mycobacteria-where do human infections come from? In Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine; Thieme Medical Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Falkinham, J.O., III; Hilborn, E.D.; Arduino, M.J.; Pruden, A.; Edwards, M.A. Epidemiology and ecology of opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens: Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacterium avium, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartrand, T.A.; Causey, J.J.; Clancy, J.L. Naegleria fowleri: An emerging drinking water pathogen. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 2014, 10, E418–E432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechtsen, H.J. Microbiological investigations of rainwater and graywater collected for toilet flushing. Water Sci. Technol. 2002, 46, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.; Goonetilleke, A.; Gardner, T. Implications of faecal indicator bacteria for the microbiological assessment of roof-harvested rainwater quality in Southeast Queensland, Australia. Can. J. Microbiol. 2010, 56, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, P.; Griffith, M.; Angles, M.; Deere, D.; Ferguson, C. Concentrations of pathogens and indicators in animal feces in the Sydney watershed. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5929–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). National Primary Drinking Water Regulations; Office of Groundwater and Drinking Water (OGWDW): Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Guidelines for Water Reuse; Office of Wastewater Management, Office of Water National Risk Management Research Laboratory, US Agency for International Development: Washington, DC, USA; Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- The Texas Water Development Board. The Texas Manual on Rainwater Harvesting; The Texas Water Development Board: Austin, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Texas Rainwater Harvesting Evaluation Committee. Rainwater Harvesting Potential and Guidelines for Texas Report to the 80th Legislature; The Texas Water Development Board: Austin, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kloss, C. Managing Wet Weather with Green Infrastructure Municipal Handbook: Rainwater Harvesting Policies. Available online: https://dep.wv.gov/WWE/Programs/stormwater/MS4/guidance/handbooks/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- NSF/ANSI 350 350-2011 (NSF). Onsite Residential and Commercial Water Reuse Treatment Systems; National Sanitation Foundation: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Macomber, P.S. Guidelines on Rainwater Catchment Systems for Hawaii; University of Hawaii at Manoa, College of Tropical Agriculture & Human Resources: Manoa, HI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA). Food Safety Modernization Act: Proposed Rule for Produce: Standards for the Growing, Harvesting, Packing, and Holding of Produce for Human Consumption; Food and Drug Administration: College Park, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, T.; Abbasi, S.A. Sources of pollution in rooftop rainwater harvesting systems and their control. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 41, 2097–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Lead-ToxFAQs; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Division of Toxicology and Human Health Sciences: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, E.C.; Ferretti, L.E.; Shucard, D.W. Effects of low level lead exposure on cognitive function in children: A review of behavioral, neuropsychological and biological evidence. Neurotoxicology 1997, 18, 237–281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 40 CFR Parts 141 and 142 National Primary Drinking Water Regulations for Lead and Copper: Short Term Regulatory Revisions and Clarifications; Final Rule; Cornell Law School: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Drinking Water Regulations and Contaminants; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- LaMotte. LaMotte 2020 we/wi Turbidimeter; 1970-EPA, 1970-ISO; LaMotte: Chestertown, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Method 200.8: Determination of Trace Elements in Water and Wastes by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry; Revision 5.4; Environmental Monitoring Systems Laboratory, Office of Research and Development: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Brandes, H.; Gyawali, P.; Sidhu, J.P.S.; Toze, S. Opportunistic pathogens in roof-captured rainwater samples, determined using quantitative PCR. Water Res. 2014, 53, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Method 1600: Membrane Filter Test Method for Enterococci in Water; Office of Water: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Method 1603: Escherichia coli (E. coli) in Water by Membrane Filtration Using Modified Membrane-Thermotolerant Escherichia coli Agar (Modified mTEC); Office of Water: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Haugland, R.A.; Siefring, S.C.; Wymer, L.J.; Brenner, K.P.; Dufour, A.P. Comparison of Enterococcus measurements in freshwater at two recreational beaches by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and membrane filter culture analysis. Water Res. 2005, 39, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chern, E.C.; King, D.; Haugland, R.; Pfaller, S. Evaluation of quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays targeting Mycobacterium avium, M. intracellulare, and M. avium subspecies paratuberculosis in drinking water biofilms. J. Water Health 2015, 13, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarian, E.J.; Bopp, D.J.; Saylors, A.; Limberger, R.J.; Musser, K.A. Design and implementation of a protocol for the detection of Legionella in clinical and environmental samples. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 62, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivière, D.; Szczebara, F.M.; Berjeaud, J.-M.; Frère, J.; Héchard, Y. Development of a real-time PCR assay for quantification of Acanthamoeba trophozoites and cysts. J. Microbiol. Methods 2006, 64, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, K.E.; Lee, D.-Y.; Trevors, J.T.; Beaudette, L.A. Application of real-time quantitative PCR for the detection of selected bacterial pathogens during municipal wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 382, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mull, B.J.; Narayanan, J.; Hill, V.R. Improved method for the detection and quantification of Naegleria fowleri in water and sediment using immunomagnetic separation and real-time PCR. J. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 2013, 608367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, M.; Nordentoft, S.; Pedersen, K.; Madsen, M. Detection of Campylobacter spp. in chicken fecal samples by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 5125–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). National Centers for Environmental Information. Available online: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/search (accessed on 1 November 2017).

- Helsel, D.R. Statistics for Censored Environmental Data Using Minitab and R; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Vieritz, A.; Goonetilleke, A.; Gardner, T. Health risk from the use of roof-harvested rainwater in Southeast Queensland, Australia, as potable or nonpotable water, determined using quantitative microbial risk assessment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 7382–7391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.A.; Ahmed, W.; Toze, S.; Haas, C.N. Human health risks for Legionella and Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) from potable and non-potable uses of roof-harvested rainwater. Water Res. 2017, 119, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fewtrell, L.; Kay, D. Quantitative microbial risk assessment with respect to Campylobacter spp. in toilets flushed with harvested rainwater. Water Environ. J. 2007, 21, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberland, M.; Bakacs, M.; Yergeau, S. An investigation of the water quality of rainwater harvesting systems. J. NACAA 2013, 6. Available online: https://www.nacaa.com/journal/index.php?jid=205 (accessed on 16 January 2018).

- Ahmed, W.; Gardner, T.; Toze, S. Microbiological quality of roof-harvested rainwater and health risks: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 2011, 40, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.; Huygens, F.; Goonetilleke, A.; Gardner, T. Real-time PCR detection of pathogenic microorganisms in roof-harvested rainwater in Southeast Queensland, Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 5490–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lye, D. Virulence characteristics of bacteria isolated from cistern water systems in rural northern Kentucky. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Rain Water Cistern Systems, Manila, Philippines, 2–4 August 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lye, D. Microbial water quality associated with rooftop rainwater harvesting—Implications for risk management. In Proceedings of the American Water Works Association Sustainable Water Management Conference and Exposition, Portland, OR, USA, 18–21 March 2012; pp. 424–437. [Google Scholar]

- Lye, D.J. Bacterial levels in cistern water systems of northern Kentucky. J. Am. Water Res. Assoc. 1987, 23, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederen, B.M.W. Legionella spp. and Legionnaires’ disease. J. Infect. 2008, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, H.M.; Meng, Z.; Henry, R.; Deletic, A.; Mccarthy, D. Current stormwater harvesting guidelines are inadequate for mitigating risk from Campylobacter during non-potable reuse activities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12498–12507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodribb, R.; Webster, P.; Farrel, D. Recurrent Campylobacter fetus subspecies bacteraemia in a febrile neutropaenicpatient linked to tank water. Commun. Dis. Intell. 1995, 19, 312–313. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, A.; Miles, R.; Bates, J. An outbreak of Campylobacter enteritis on an island resort, north Queensland. Commun. Dis. Intell. 1999, 23, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Struewing, I.; Yelton, S.; Ashbolt, N. Molecular survey of occurrence and quantity of Legionella spp., Mycobacterium spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and amoeba hosts in municipal drinking water storage tank sediments. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonett, D.G.; Wright, T.A. Sample size requirements for estimating Pearson, Kendall and Spearman correlations. Psychometrika 2000, 65, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PWD. Green Infrastructure, on Philadelphia Water Department. 2012. Available online: http://www.phillywatersheds.org/what_were_doing/green_infrastructure (accessed on 31 October 2017).

- Schoen, M.E.; Ashbolt, N.J.; Jahne, M.A.; Garland, J. Risk-based enteric pathogen reduction targets for non-potable and direct potable use of roof runoff, stormwater, and greywater. Microb. Risk Anal. 2017, 5, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, M.E.; Garland, J. Review of pathogen treatment reductions for onsite non-potable reuse of alternative source waters. Microb. Risk Anal. 2015, 5, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Mean (Range) |

|---|---|

| pH | 6.25 (4.82–9.64) |

| Conductivity(µS) | 149 (37.8–648) |

| Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) (ppm) | 101 (18.6–780) |

| Temperature (°C) | 26.6 (22.5–30.5) |

| Dissolved Oxygen (mg/L) | 6.26 (2.60–10.6) |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 4.27 (0.03–61.6) |

| Parameter (Units) | Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) | Mean of Positive Samples (Range) | No. of Positive Sample/Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli/100 mL | 1 | 2.92 × 102 (1–>103)a | 16/26 (61.5) |

| Enterococcus spp./100 mL | 1 | 1.55 × 102 (1–>103)a | 20/26 (76.9) |

| Acanthamoeba spp./L | 333 | 7.48 × 104 (1.01 × 103–4.68 × 105) | 7/38 (18.4) |

| C. jejuni/L | 33.3 | 2.82 × 102 | 1/38 (2.6) |

| Legionella spp./L | 333 | 2.47 × 104 (3.37 × 102–1.63 × 105) | 22/38 (57.9) |

| L. pneumophila/L | 33.3 | ND b | 0/38 (0) |

| M. avium/L | 33.3 | 1.30 × 103 (1.80 × 102–8.10 × 103) | 8/38 (21.1) |

| M. intracellulare/L | 33.3 | 2.59 × 103 (8.41 × 101–2.83 × 104) | 17/38 (44.7) |

| N. fowleri/L | 33.3 | ND | 0/38 (0) |

| P. aeruginosa/L | 333 | 4.57 × 107 (2.95 × 103–9.14 × 107) | 2/38 (5.3) |

| Lead (µg/L) | 3 | 79.4 (3–1282) | 23/26 (88.5) |

| Zinc (µg/L) | 25 | 255.3 (29–2660) | 23/26 (88.5) |

| Parameter [Kendall’s Tau, (P)] a | E. coli | Enterococcus spp. | Acanthamoeba spp. | Legionella spp. | M. avium | M. intracellulare | Lead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus spp. | 0.520 (<0.001) | ||||||

| Acanthamoeba spp. | 0.015 (0.880) | −0.009 (0.942) | |||||

| Legionella spp. | −0.160 (0.235) | −0.102 (0.470) | −0.014 (0.848) | ||||

| M. avium | −0.157 (0.114) | −0.031 (0.783) | 0.010 (0.841) | 0.161 (0.025) | |||

| M. intracellulare | 0.102 (0.411) | 0.068 (0.602) | 0.058 (0.358) | −0.118 (0.225) | −0.048 (0.480) | ||

| Lead | 0.271 (0.045) | 0.246 (0.077) | 0.151 (0.081) | 0.228 (0.101) | 0.009 (0.951) | 0.025 (0.862) | |

| Zinc | 0.061 (0.645) | 0.102 (0.476) | 0.059 (0.516) | 0.129 (0.358) | −0.052 (0.627) | −0.006 (0.980) | 0.295 (0.035) |

| Parameter [Kendall’s Tau, (P)] a | pH | Conductivity (µS) | Total Dissolved Solids (ppm) | Temp. (°C) | Dissolved Oxygen (mg/L) | Turbidity (NTU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | −0.222 (0.103) | 0.086 (0.535) | 0.123 (0.370) | −0.052 (0.713) | 0.080 (0.565) | 0.193 (0.168) |

| Enterococcus spp. | −0.148 (0.295) | 0.154 (0.275) | 0.191 (0.175) | −0.062 (0.672) | 0.157 (0.265) | 0.167 (0.249) |

| Acanthamoeba spp. | 0.114 (0.194) | 0.132 (0.131) | 0.182 (0.037) | −0.019 (0.857) | 0.012 (0.914) | 0.047 (0.578) |

| Legionella spp. | 0.129 (0.359) | 0.135 (0.336) | 0.080 (0.576) | 0.074 (0.607) | 0.006 (0.982) | 0.010 (0.962) |

| M. avium | −0.006 (0.976) | 0.025 (0.832) | 0.012 (0.928) | −0.062 (0.564) | −0.095 (0.362) | 0.117 (0.247) |

| M. intracellulare | −0.071 (0.588) | 0.080 (0.538) | 0.105 (0.416) | −0.003 (>0.999) | −0.025 (0.863) | <0.001 (>0.999) |

| Lead | 0.059 (0.690) | 0.403 (0.004) | 0.440 (0.002) | 0.231 (0.101) | −0.077 (0.595) | 0.032 (0.026) |

| Zinc | −0.025 (0.877) | 0.037 (0.808) | 0.098 (0.494) | 0.074 (0.611) | 0.074 (0.611) | 0.197 (0.175) |

| Parameter | Overhanging Trees | Presence of Wildlife | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 12) | No (n = 13) | Yes (n = 10) | No (n = 3) | |

| E. coli | 11 (91.7) | 12 (92.3) | 7 (70.0) | 2 (66.7) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 11 (91.7) | 8 (61.5) | 8 (80.0) | 3 (100) |

| Acanthamoeba spp. | 1 (8.33) | 4 (30.8) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (33.3) |

| C. jejuni | 1 (8.33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Legionella spp. | 7 (58.3) | 11 (84.6) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (100) |

| M. avium | 2 (16.7) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) |

| M. intracellulare | 6 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 7 (70.0) | 1 (33.3) |

| P. aeruginosa | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamilton, K.A.; Parrish, K.; Ahmed, W.; Haas, C.N. Assessment of Water Quality in Roof-Harvested Rainwater Barrels in Greater Philadelphia. Water 2018, 10, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10020092

Hamilton KA, Parrish K, Ahmed W, Haas CN. Assessment of Water Quality in Roof-Harvested Rainwater Barrels in Greater Philadelphia. Water. 2018; 10(2):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10020092

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamilton, Kerry A., Kerrianne Parrish, Warish Ahmed, and Charles N. Haas. 2018. "Assessment of Water Quality in Roof-Harvested Rainwater Barrels in Greater Philadelphia" Water 10, no. 2: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10020092

APA StyleHamilton, K. A., Parrish, K., Ahmed, W., & Haas, C. N. (2018). Assessment of Water Quality in Roof-Harvested Rainwater Barrels in Greater Philadelphia. Water, 10(2), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10020092