Flood Prediction Using Machine Learning Models: Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

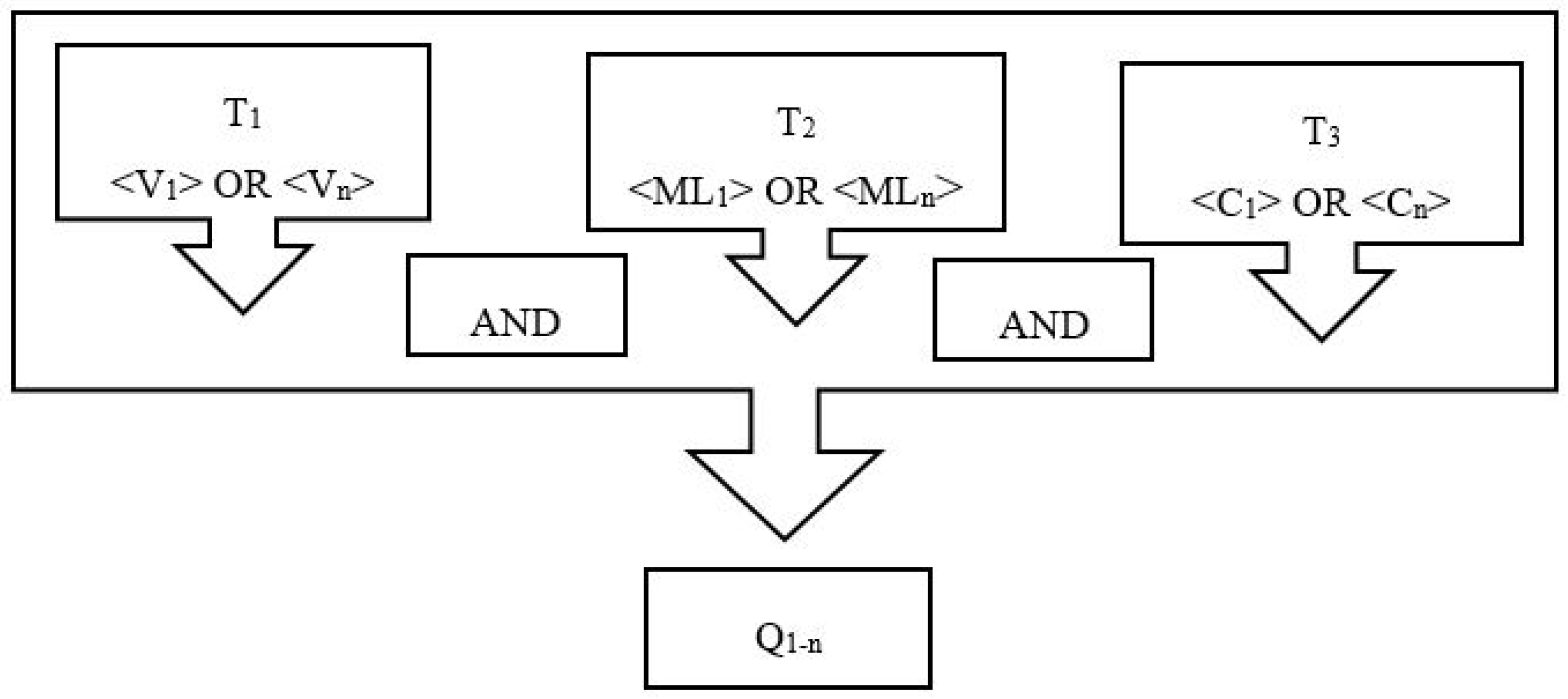

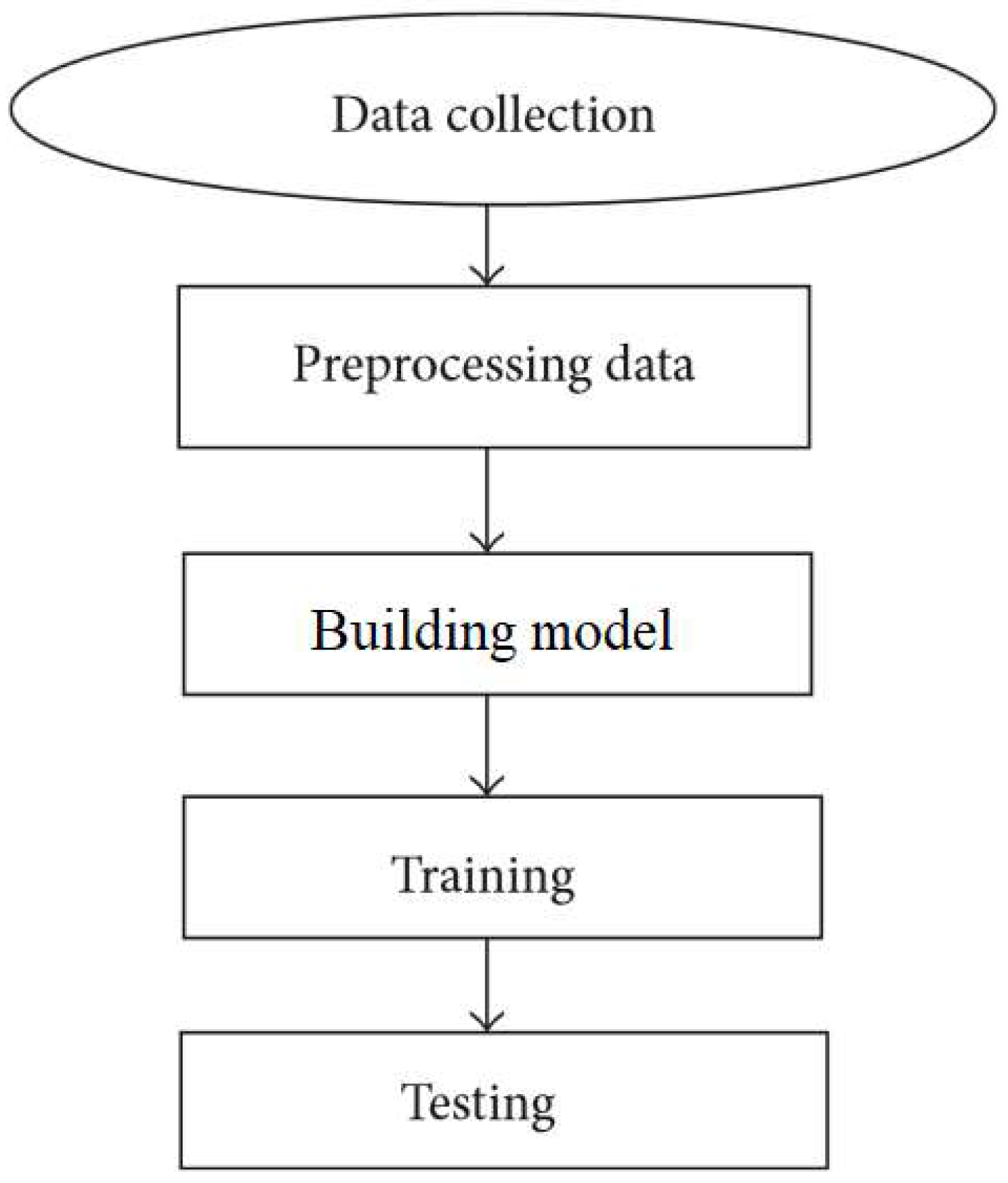

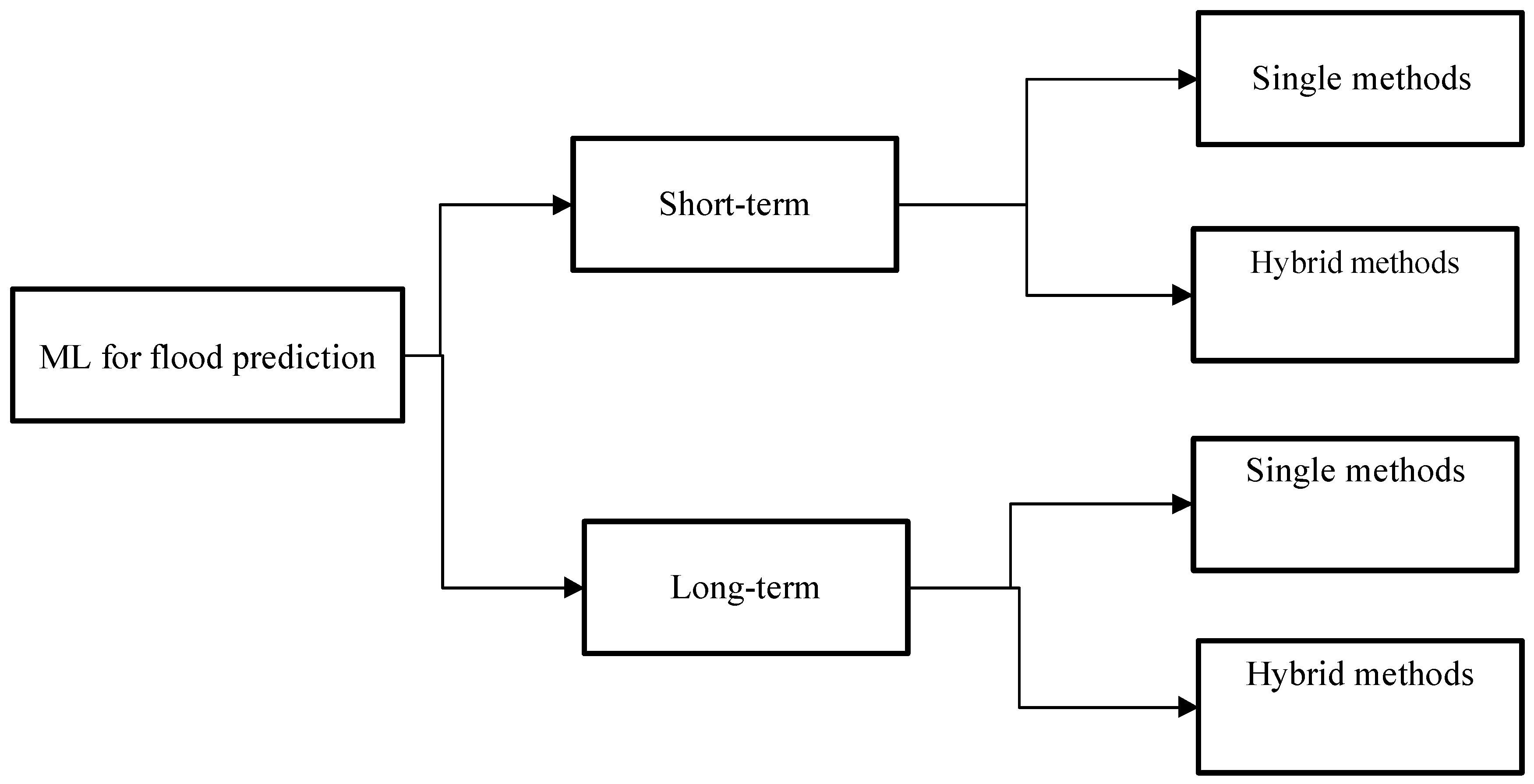

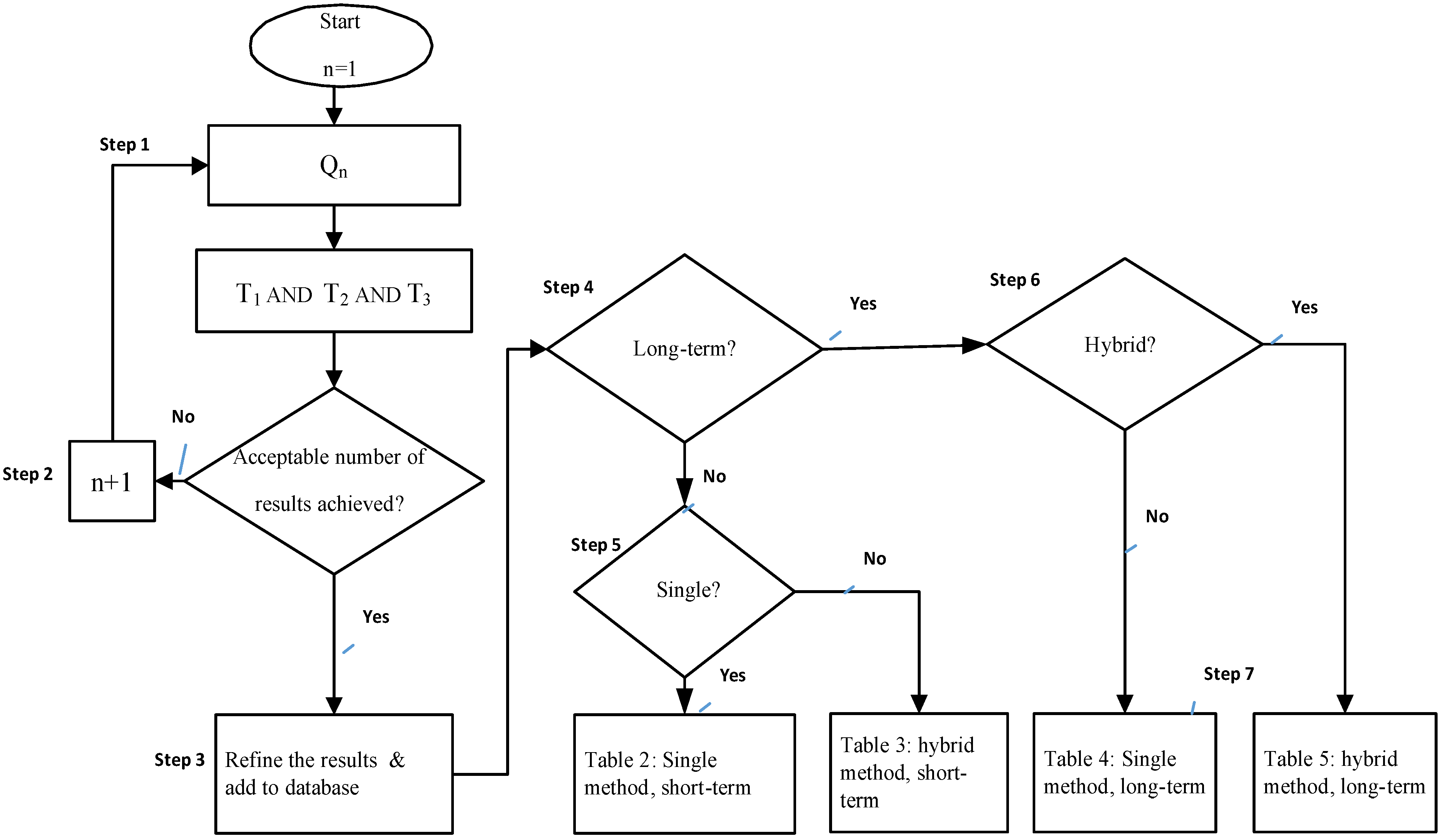

2. Method and Outline

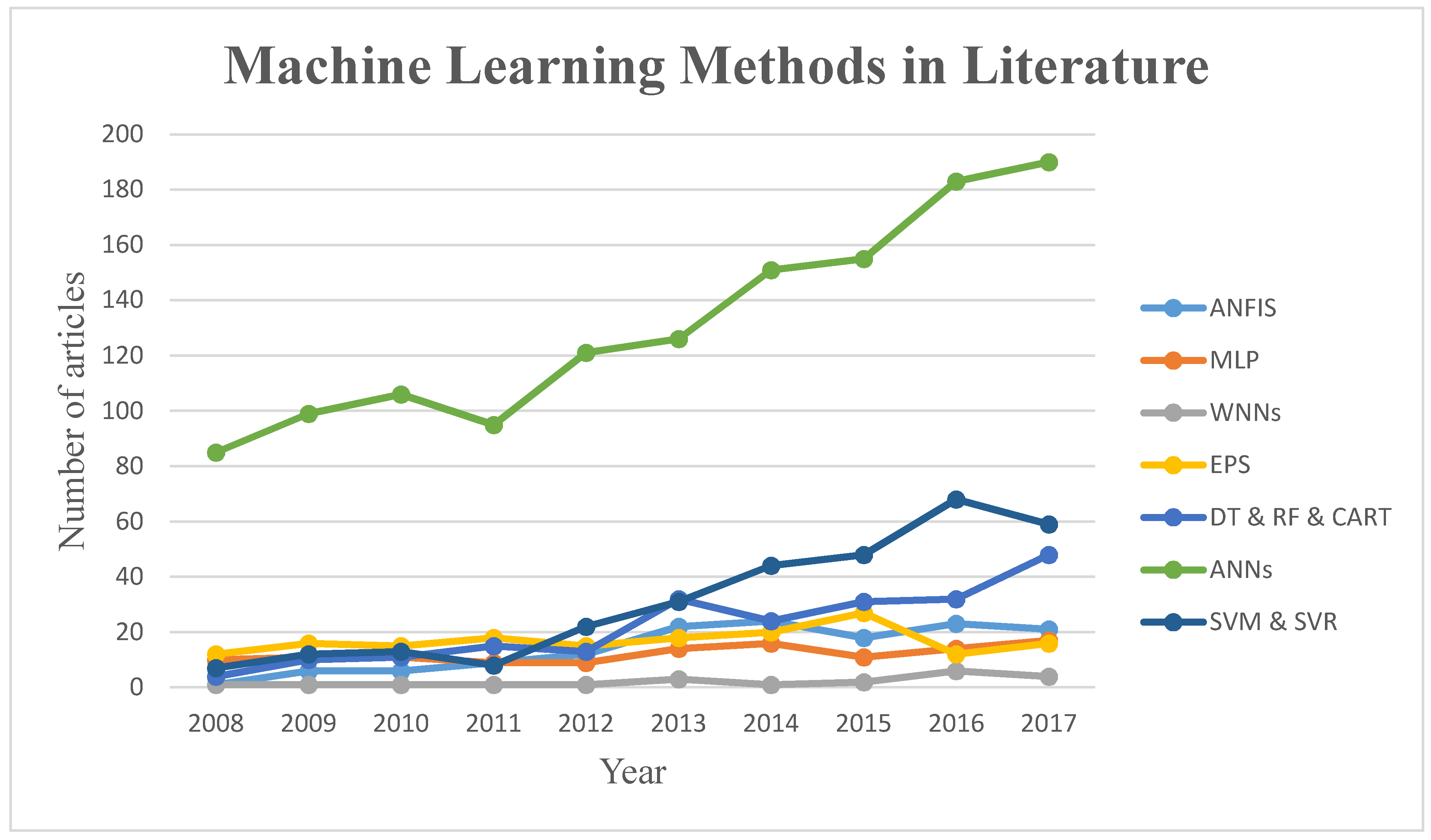

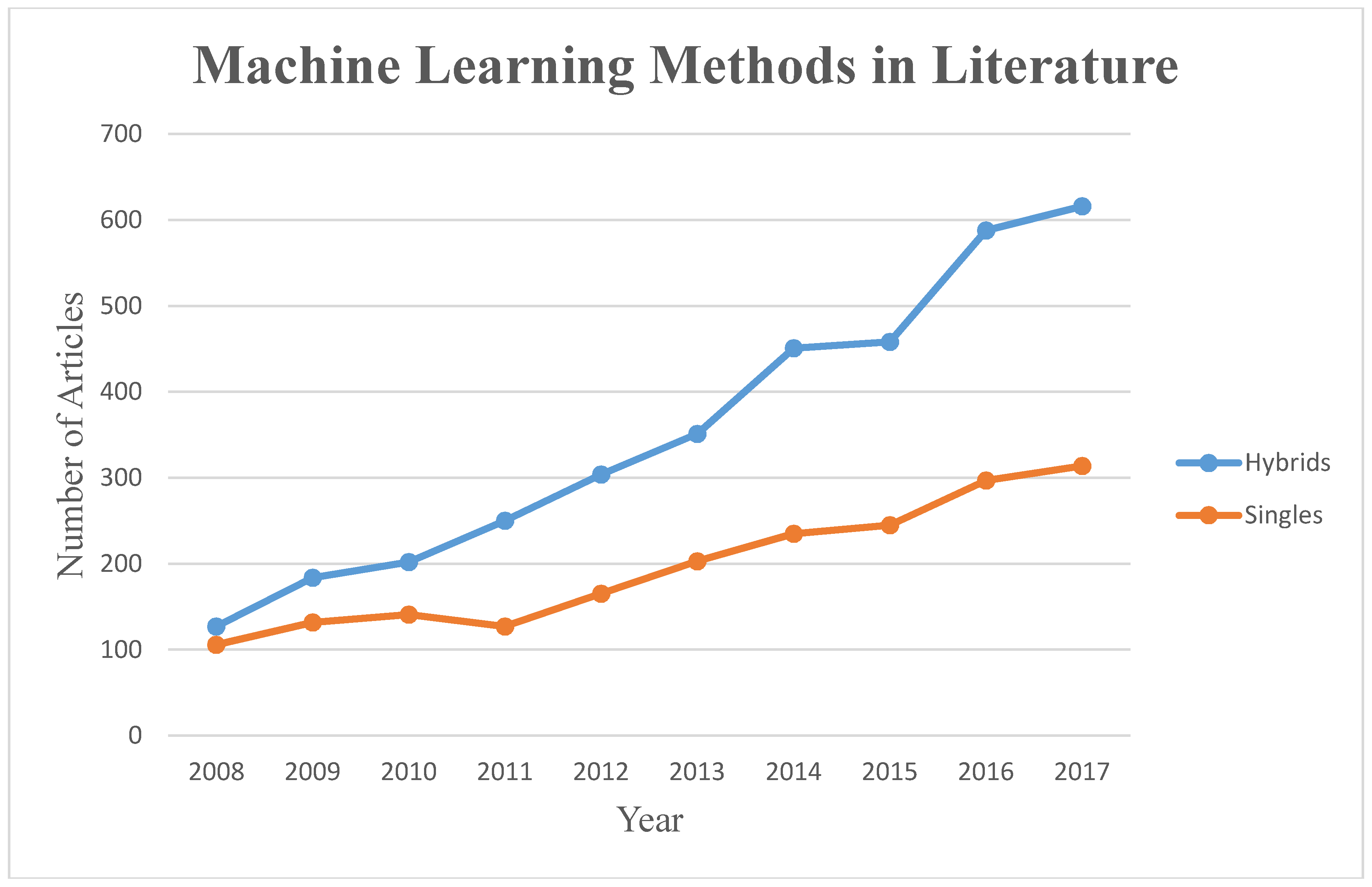

3. State of the Art of ML Methods in Flood Prediction

3.1. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

3.2. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)

3.3. Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS)

3.4. Wavelet Neural Network (WNN)

3.5. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

3.6. Decision Tree (DT)

3.7. Ensemble Prediction Systems (EPSs)

3.8. Classification of ML Methods and Applications

4. Short-Term Flood Prediction with ML

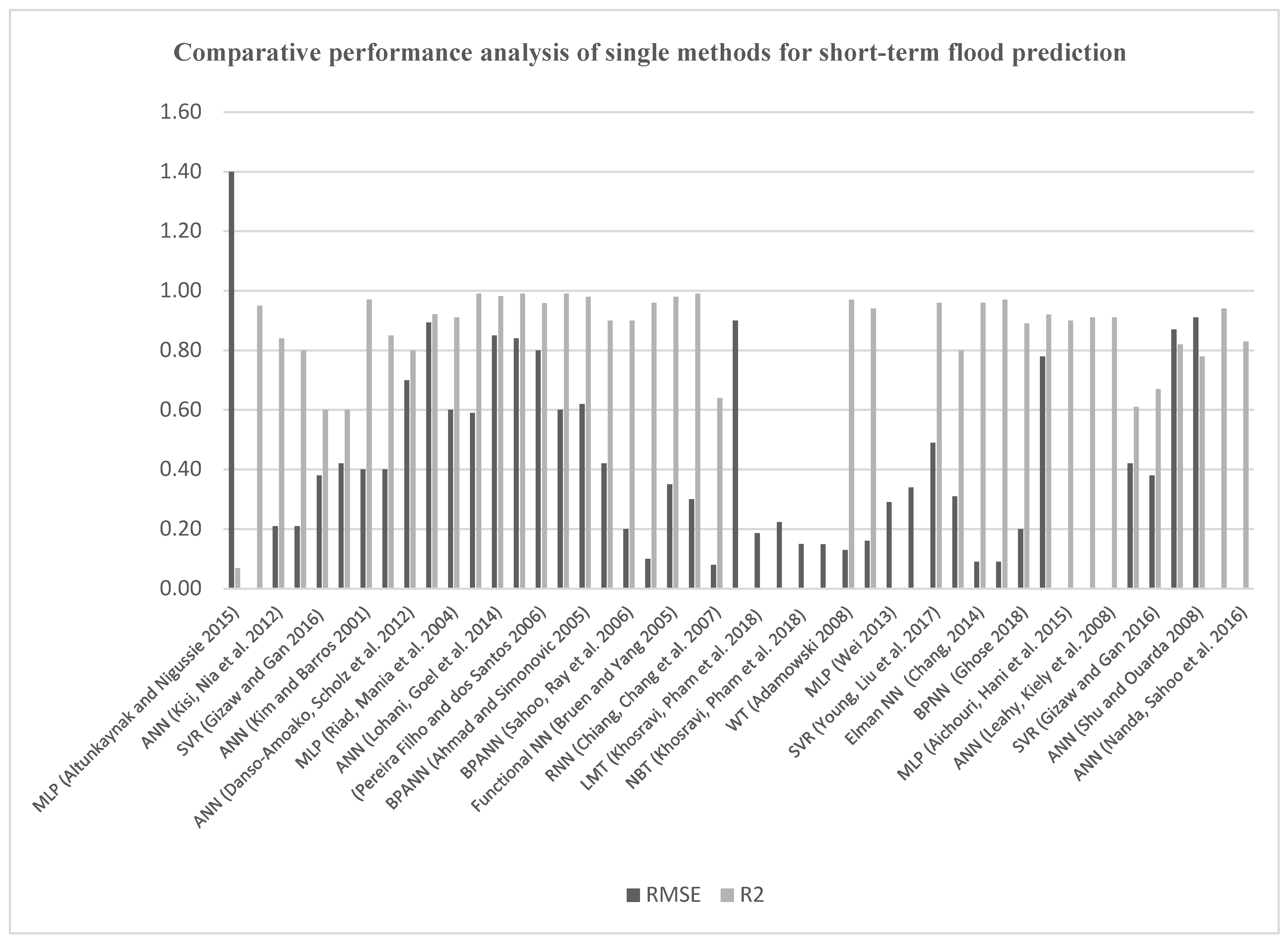

4.1. Short-Term Flood Prediction Using Single ML Methods

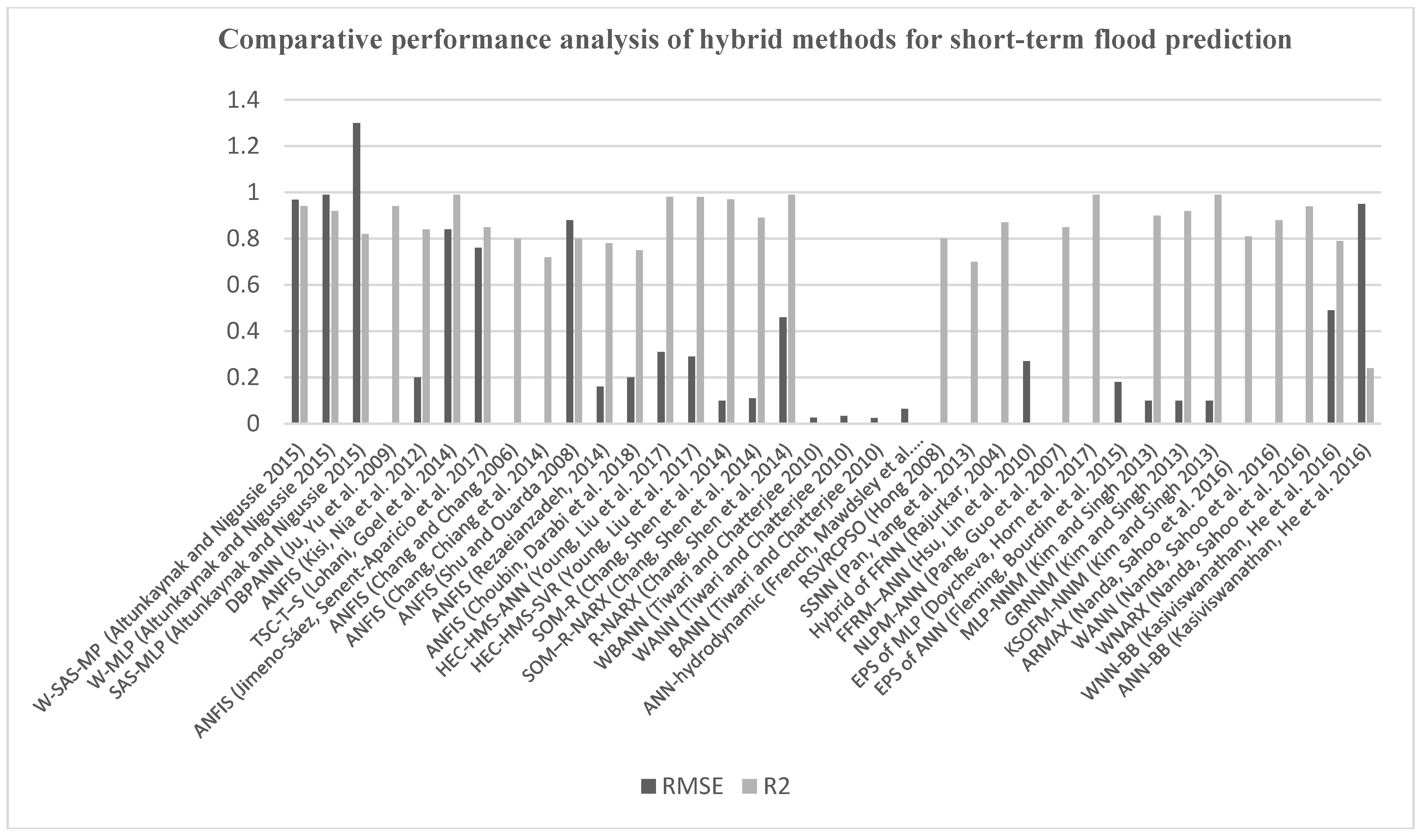

4.2. Short-Term Flood Prediction Using Hybrid ML Methods

4.3. Comparative Performance Analysis

5. Long-Term Flood Prediction with ML

5.1. Long-Term Flood Prediction Using Single ML Methods

5.2. Long-Term Flood Prediction Using Hybrid ML Methods

6. Comparative Performance Analysis and Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclatures

| WMO | World meteorological organization |

| GCM | Global circulation models |

| SPOTA | Seasonal Pacific Ocean temperature analysis |

| ANN | Artificial neural networks |

| POTA | Pacific Ocean temperature analysis |

| QPE | Quantitative precipitation estimation |

| CLIM | Climatology average method |

| EOF | Empirical orthogonal function |

| MLR | Multiple linear regressions |

| QPF | Quantitative precipitation forecasting |

| MNLR | Multiple nonlinear regressions |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MLR | Multiple linear regression |

| ANN | Neural networks |

| WNN | Wavelet-based neural network |

| ARIMA | Auto regressive integrated moving average |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| FFA | Flood frequency analyses |

| QRT | Quantile regression techniques |

| SPOTA | Seasonal Pacific Ocean temperature analysis |

| SVM | Support vector machines |

| LS-SVM | Least-square support vector machines |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| VRM | Vector Regression Machine |

| FFNN | Feed-forward neural network |

| FBNN | Feed-backward networks |

| MLP | Multilayer perceptron |

| ANFIS | Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system |

| BPNN | Backpropagation neural network |

| SVR | Support vector regression |

| LR | Linear regression |

| FIS | Fuzzy inference system |

| CART | Classification and regression tree |

| LMT | Logistic model trees |

| NWP | Numerical weather prediction |

| NBT | Naive Bayes trees |

| ARMA | Autoregressive moving averaging |

| REPT | Reduced-error pruning trees |

| DT | Decision tree |

| ELM | Extreme learning machine |

| EPS | Ensemble prediction systems |

| SNIP | Source normalized impact per paper |

| SRM | Structural risk minimization |

| AR | Autoregressive |

| SJR | SCImago journal rank |

| ARMAX | Linear autoregressive moving average with exogenous inputs |

| LMT | Logistic model trees |

| ARMA | Autoregressive moving averaging |

| ADT | Alternating decision trees |

| NARX network | Nonlinear autoregressive network with exogenous inputs |

| RMSE | Root-mean-square error |

| RFFA | Regional flood frequency analysis |

| NLR | Nonlinear regression |

| AR | Autoregressive |

| WARM | Wavelet autoregressive model |

| NLR-R | Nonlinear regression with regionalization approach |

| E | Nash Sutcliffe index |

| FR | Frequency ratio |

| SOM | Self-organizing map |

| CHIM | Cluster-based hybrid inundation model |

| FFRM | Flash flood routing model |

| KGE | Kling-Gupta efficiency |

| AME | ANN-based monsoon rainfall enhancement |

| SSNN | State-space neural network |

| SSL | Suspended sediment load |

| NSE | Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency |

| E-CHAID | Exhaustive CHAID |

| CHAID | Chi-squared automatic interaction detector |

| CLIM | Climatology average model |

| HEC–HMS | Hydrologic engineering left–hydrologic modeling system |

| SOM | Self-organizing map |

| PBIAS | Percent bias |

| NLPM | Nonlinear perturbation model |

| RF | Rotation forest |

| KSOFM-NNM | Kohonen self-organizing feature maps neural networks model |

| DBP | Division-based backpropagation |

| DBPANN | DBP neural network |

| NLPM-ANN | Nonlinear perturbation model based on neural network |

| GRNNM | Generalized regression neural networks model |

| IIS | Iterative input selection |

| EEMD | Ensemble empirical mode decomposition |

| ANNE | Artificial neural network ensembles |

| DWT | Discrete wavelet transform |

| SFF | Seasonal flood forecasting |

| MP | Water monitoring points |

| WBANN | Wavelet–bootstrap–ANN |

| HBI | Hilsenhoff’s biotic index |

| RT | Regression trees |

| EMD | Empirical mode decomposition |

| LLR | Local linear regression |

| BFGS | Broyden Fletcher Goldfarb Shanno |

| M-EMD | Modified empirical mode decomposition |

| IIS | Iterative input selection |

| SAR | Seasonal first-order autoregressive |

| BFGSNN | Broyden Fletcher Goldfarb Shanno neural network |

| GRNN | Artificial neural networks including generalized regression network |

| T–S | Takagi–Sugeno |

| WLGP | Wavelet linear genetic programming |

| E | Nash coefficients |

| TSC-T–S | Clustering based Takagi–Sugeno |

| TCs | Tropical cyclones |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

- Danso-Amoako, E.; Scholz, M.; Kalimeris, N.; Yang, Q.; Shao, J. Predicting dam failure risk for sustainable flood retention basins: A generic case study for the wider greater manchester area. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2012, 36, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Ozbay, K.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, H. Evacuation zone modeling under climate change: A data-driven method. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2017, 23, 04017013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, M. Learning Lessons from the 2007 Floods; Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lohani, A.K.; Goel, N.; Bhatia, K. Improving real time flood forecasting using fuzzy inference system. J. Hydrol. 2014, 509, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, A.; Bathla, Y.; Varkonyi-Koczy, A. Predicting the Future Using Web Knowledge: State of the Art Survey. In Recent Advances in Technology Research and Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Hendon, H.H. Representation and prediction of the indian ocean dipole in the poama seasonal forecast model. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2009, 135, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, D.K. Hydrologic procedures of storm event watershed models: A comprehensive review and comparison. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 3472–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabile, P.; Costanzo, C.; Macchione, F. A storm event watershed model for surface runoff based on 2D fully dynamic wave equations. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 554–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cea, L.; Garrido, M.; Puertas, J. Experimental validation of two-dimensional depth-averaged models for forecasting rainfall–runoff from precipitation data in urban areas. J. Hydrol. 2010, 382, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pato, J.; Caviedes-Voullième, D.; García-Navarro, P. Rainfall/runoff simulation with 2D full shallow water equations: Sensitivity analysis and calibration of infiltration parameters. J. Hydrol. 2016, 536, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviedes-Voullième, D.; García-Navarro, P.; Murillo, J. Influence of mesh structure on 2D full shallow water equations and SCS curve number simulation of rainfall/runoff events. J. Hydrol. 2012, 448, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabile, P.; Costanzo, C.; Macchione, F. Comparative analysis of overland flow models using finite volume schemes. J. Hydroinform. 2012, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Liang, Q.; Ming, X.; Hou, J. An efficient and stable hydrodynamic model with novel source term discretization schemes for overland flow and flood simulations. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 3730–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Wood, E.F.; Burges, S.J. A simple hydrologically based model of land surface water and energy fluxes for general circulation models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1994, 99, 14415–14428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabile, P.; Macchione, F. Enhancing river model set-up for 2-D dynamic flood modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 67, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.; Sudheer, K.; Rangan, D.; Ramasastri, K. Short-term flood forecasting with a neurofuzzy model. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Sanders, B.F.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Guinot, V. Urban flood modeling with porous shallow-water equations: A case study of model errors in the presence of anisotropic porosity. J. Hydrol. 2015, 523, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Honert, R.C.; McAneney, J. The 2011 brisbane floods: Causes, impacts and implications. Water 2011, 3, 1149–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Georgakakos, K.P. Operational rainfall prediction on meso-γ scales for hydrologic applications. Water Resour. Res. 1996, 32, 987–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, D.; Robertson, D.; Wang, Q.; Pagano, T.; Hapuarachchi, H. Evaluation of numerical weather prediction model precipitation forecasts for short-term streamflow forecasting purpose. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 1913–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, V.; Tsakiris, G. A hybrid method for flood simulation in small catchments combining hydrodynamic and hydrological techniques. J. Hydrol. 2016, 540, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bout, B.; Jetten, V. The validity of flow approximations when simulating catchment-integrated flash floods. J. Hydrol. 2018, 556, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabile, P.; Macchione, F.; Natale, L.; Petaccia, G. Flood mapping using lidar dem. Limitations of the 1-D modeling highlighted by the 2-D approach. Nat. Hazards 2015, 77, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, M.; Banihabib, M.E.; Behbahani, S.M.R. Parameters estimate of autoregressive moving average and autoregressive integrated moving average models and compare their ability for inflow forecasting. J. Math. Stat. 2012, 8, 330–338. [Google Scholar]

- Adamowski, J.; Fung Chan, H.; Prasher, S.O.; Ozga-Zielinski, B.; Sliusarieva, A. Comparison of multiple linear and nonlinear regression, autoregressive integrated moving average, artificial neural network, and wavelet artificial neural network methods for urban water demand forecasting in montreal, Canada. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, M.; Banihabib, M.E.; Behbahani, S.M.R. Comparison of the ARMA, ARIMA, and the autoregressive artificial neural network models in forecasting the monthly inflow of Dez dam reservoir. J. Hydrol. 2013, 476, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.T.; Maidment, D.R.; Larry, W. Mays. Applied hydrology; International Edition; MacGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1988; p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, K.; Rahman, A.; Fang, G.; Shrestha, S. Application of artificial neural networks in regional flood frequency analysis: A case study for australia. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2014, 28, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, C.N.; Vogel, R.M. Probability distribution of low streamflow series in the united states. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2002, 7, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, B.P.; Krishnamurti, T. Ensemble forecast of a typhoon flood event. Weather Forecast. 2001, 16, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, K.; Rahman, A. Regional flood frequency analysis in eastern australia: Bayesian GLS regression-based methods within fixed region and ROI framework–quantile regression vs. Parameter regression technique. J. Hydrol. 2012, 430, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.A. Hydrology for Water Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhoven, E.; Gan, T.Y. A modified ISBA surface scheme for modeling the hydrology of Athabasca river basin with GCM-scale data. Adv. Water Resour. 2006, 29, 808–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnash, R.J.; Ferral, R.L.; McGuire, R.A. A Generalized Streamflow Simulation System, Conceptual Modeling for Digital Computers; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, D.; Kanae, S.; Kim, H.; Oki, T. A physically based description of floodplain inundation dynamics in a global river routing model. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, R.; Stone, R. A comparison of two seasonal rainfall forecasting systems for Australia. Aust. Meteorol. Oceanogr. J. 2010, 60, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekanik, F.; Imteaz, M.; Gato-Trinidad, S.; Elmahdi, A. Multiple regression and artificial neural network for long-term rainfall forecasting using large scale climate modes. J. Hydrol. 2013, 503, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, A.; Rabczuk, T.; Varkonyi-Koczy, A.R. Reviewing the novel machine learning tools for materials design. In Recent Advances in Technology Research and Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Abbot, J.; Marohasy, J. Input selection and optimisation for monthly rainfall forecasting in Queensland, Australia, using artificial neural networks. Atmos. Res. 2014, 138, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.I.; Wikle, C.K. A bayesian quantitative precipitation nowcast scheme. Weather Forecast. 2005, 20, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, B.; Hall, J.; Disse, M.; Schumann, A. Fluvial flood risk management in a changing world. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, J. Short-term inflow forecasting using an artificial neural network model. Hydrol. Process. 2002, 16, 2423–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-García, E.; Salcedo-Sanz, S.; Casanova-Mateo, C. Accurate precipitation prediction with support vector classifiers: A study including novel predictive variables and observational data. Atmos. Res. 2014, 139, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Matsumi, Y.; Pan, S.; Mase, H. A real-time forecast model using artificial neural network for after-runner storm surges on the Tottori Coast, Japan. Ocean Eng. 2016, 122, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, A.; Edalatifar, M. A.; Edalatifar, M. A Hybrid Neuro-Fuzzy Algorithm for Prediction of Reference Evapotranspiration. In Recent Advances in Technology Research and Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Dineva, A.; Várkonyi-Kóczy, A.R.; Tar, J.K. Fuzzy expert system for automatic wavelet shrinkage procedure selection for noise suppression. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 18th International Conference on Intelligent Engineering Systems (INES), Tihany, Hungary, 3–5 July 2014; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Suykens, J.A.; Vandewalle, J. Least squares support vector machine classifiers. Neural Process. Lett. 1999, 9, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizaw, M.S.; Gan, T.Y. Regional flood frequency analysis using support vector regression under historical and future climate. J. Hydrol. 2016, 538, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherei Ghazvinei, P.; Hassanpour Darvishi, H.; Mosavi, A.; Yusof, K.B.W.; Alizamir, M.; Shamshirband, S.; Chau, K.W. Sugarcane growth prediction based on meteorological parameters using extreme learning machine and artificial neural network. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2018, 12, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiviswanathan, K.; He, J.; Sudheer, K.; Tay, J.-H. Potential application of wavelet neural network ensemble to forecast streamflow for flood management. J. Hydrol. 2016, 536, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravansalar, M.; Rajaee, T.; Kisi, O. Wavelet-linear genetic programming: A new approach for modeling monthly streamflow. J. Hydrol. 2017, 549, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, A.; Rabczuk, T. Learning and intelligent optimization for material design innovation. In Learning and Intelligent Optimization; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 358–363. [Google Scholar]

- Dandagala, S.; Reddy, M.S.; Murthy, D.S.; Nagaraj, G. Artificial neural networks applications in groundwater hydrology—A review. Artif. Intell. Syst. Mach. Learn. 2017, 9, 182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Deka, P.C. Support vector machine applications in the field of hydrology: A review. Appl. Soft Comput. 2014, 19, 372–386. [Google Scholar]

- Fotovatikhah, F.; Herrera, M.; Shamshirband, S.; Chau, K.-W.; Faizollahzadeh Ardabili, S.; Piran, M.J. Survey of computational intelligence as basis to big flood management: Challenges, research directions and future work. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2018, 12, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizollahzadeh Ardabili, S.; Najafi, B.; Alizamir, M.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Rabczuk, T. Using SVM-RSM and ELM-RSM Approaches for Optimizing the Production Process of Methyl and Ethyl Esters. Energies 2018, 11, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.T.; Yang, C.-C. Improving measurement invariance assessments in survey research with missing data by novel artificial neural networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 10456–10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapalan, M.; Blöschl, G.; Merz, R.; Gutknecht, D. Linking flood frequency to long-term water balance: Incorporating effects of seasonality. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, H.R.; Jain, A.; Dandy, G.C.; Sudheer, K.P. Methods used for the development of neural networks for the prediction of water resource variables in river systems: Current status and future directions. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafdani, E.K.; Nia, A.M.; Pahlavanravi, A.; Ahmadi, A.; Jajarmizadeh, M. Research article daily rainfall-runoff prediction and simulation using ANN, ANFIS and conceptual hydrological MIKE11/NAM models. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2013, 1, 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, C. Flash flood forecasting: What are the limits of predictability? Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2007, 133, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.-J.; Breidenbach, J. Real-time correction of spatially nonuniform bias in radar rainfall data using rain gauge measurements. J. Hydrometeorol. 2002, 3, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecu, M.; Krajewski, W. A large-sample investigation of statistical procedures for radar-based short-term quantitative precipitation forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2000, 239, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, R.A.; Zhang, J.; Gourley, J.J.; Howard, K.W. Weather radar coverage over the contiguous united states. Weather Forecast. 2002, 17, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campolo, M.; Andreussi, P.; Soldati, A. River flood forecasting with a neural network model. Water Resour. Res. 1999, 35, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, O.; Sudheer, K.; Srinivasan, K. Improved higher lead time river flow forecasts using sequential neural network with error updating. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 2014, 62, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Ouarda, T. Regional flood frequency analysis at ungauged sites using the adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. J. Hydrol. 2008, 349, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Chua, L.H.C.; Quek, C.; Qin, X. A fully-online neuro-fuzzy model for flow forecasting in basins with limited data. J. Hydrol. 2017, 545, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.-S.; Yang, T.-C.; Chen, S.-Y.; Kuo, C.-M.; Tseng, H.-W. Comparison of random forests and support vector machine for real-time radar-derived rainfall forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2017, 552, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, V.; Baghanam, A.H.; Adamowski, J.; Kisi, O. Applications of hybrid wavelet–artificial intelligence models in hydrology: A review. J. Hydrol. 2014, 514, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, M.R.; Amin, S.; Khalili, D.; Singh, V.P. Daily outflow prediction by multi layer perceptron with logistic sigmoid and tangent sigmoid activation functions. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 2673–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Simonovic, S. Streamflow forecast and reservoir operation performance assessment under climate change. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chau, K.-W. Data-driven models for monthly streamflow time series prediction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2010, 23, 1350–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, J.; Wahab, S.H. Heavy rainfall forecasting model using artificial neural network for flood prone area. In It Convergence and Security 2017; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kar, A.K.; Lohani, A.K.; Goel, N.K.; Roy, G.P. Development of flood forecasting system using statistical and ANN techniques in the downstream catchment of mahanadi basin, india. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2010, 2, 880. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Prasad Indurthy, S. Closure to “comparative analysis of event-based rainfall-runoff modeling techniques—Deterministic, statistical, and artificial neural networks” by ASHU JAIN and SKV prasad indurthy. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2004, 9, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohani, A.; Kumar, R.; Singh, R. Hydrological time series modeling: A comparison between adaptive neuro-fuzzy, neural network and autoregressive techniques. J. Hydrol. 2012, 442, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanty, R.; Desmukh, T.S. Application of artificial neural network in hydrology—A review. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Res. 2015, 4, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kişi, O. Streamflow forecasting using different artificial neural network algorithms. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2007, 12, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseldin, A.Y. Artificial neural network model for river flow forecasting in a developing country. J. Hydroinform. 2010, 12, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrzadeh, H.; Sarukkalige, R.; Jayawardena, A. Impact of multi-resolution analysis of artificial intelligence models inputs on multi-step ahead river flow forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2013, 507, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Eli, R.N. Neural-network models of rainfall-runoff process. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 1995, 121, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormina, R.; Chau, K.-W.; Sethi, R. Artificial neural network simulation of hourly groundwater levels in a coastal aquifer system of the Venice Lagoon. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2012, 25, 1670–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalaiah, K.; Deo, M. River stage forecasting using artificial neural networks. J. Hydrol. Eng. 1998, 3, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagoulia, D. Artificial neural networks and high and low flows in various climate regimes. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2006, 51, 563–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagoulia, D.; Tsekouras, G.; Kousiouris, G. A multi-stage methodology for selecting input variables in ann forecasting of river flows. Glob. Nest J. 2017, 19, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, R.C.; Şahin, M. Application of the artificial neural network model for prediction of monthly standardized precipitation and evapotranspiration index using hydrometeorological parameters and climate indices in Eastern Australia. Atmos. Res. 2015, 161, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, P.; Dibike, Y.B.; Anctil, F. Downscaling precipitation and temperature with temporal neural networks. J. Hydrometeorol. 2005, 6, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoof, J.T.; Pryor, S. Downscaling temperature and precipitation: A comparison of regression-based methods and artificial neural networks. Int. J. Climatol. 2001, 21, 773–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.; Shamsudin, S.; Harun, S.; Malek, M.A.; Hamidon, N. Suitability of ANN applied as a hydrological model coupled with statistical downscaling model: A case study in the northern area of peninsular Malaysia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-S.; Xiao, X.-C. Predicting chaotic time series using recurrent neural network. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2000, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.-B.; Zhu, Q.-Y.; Siew, C.-K. Extreme learning machine: Theory and applications. Neurocomputing 2006, 70, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.R.; Cannon, A.J.; Hsieh, W.W. Forecasting daily streamflow using online sequential extreme learning machines. J. Hydrol. 2016, 537, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Z.M.; Jaafar, O.; Deo, R.C.; Kisi, O.; Adamowski, J.; Quilty, J.; El-Shafie, A. Stream-flow forecasting using extreme learning machines: A case study in a semi-arid region in Iraq. J. Hydrol. 2016, 542, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, G.; Ray, C. Flow forecasting for a Hawaii stream using rating curves and neural networks. J. Hydrol. 2006, 317, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Singh, V.P. Flood forecasting using neural computing techniques and conceptual class segregation. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2013, 49, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, S.; Mania, J.; Bouchaou, L.; Najjar, Y. Rainfall-runoff model using an artificial neural network approach. Math. Comput. Model. 2004, 40, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil Kumar, A.; Sudheer, K.; Jain, S.; Agarwal, P. Rainfall-runoff modelling using artificial neural networks: Comparison of network types. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 2005, 19, 1277–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Soft computing and fuzzy logic. In Fuzzy Sets, Fuzzy Logic, and Fuzzy Systems: Selected Papers by Lotfi a Zadeh; World Scientific: Singapore, 1996; pp. 796–804. [Google Scholar]

- Choubin, B.; Khalighi-Sigaroodi, S.; Malekian, A.; Ahmad, S.; Attarod, P. Drought forecasting in a semi-arid watershed using climate signals: A neuro-fuzzy modeling approach. J. Mt. Sci. 2014, 11, 1593–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubin, B.; Khalighi-Sigaroodi, S.; Malekian, A.; Kişi, Ö. Multiple linear regression, multi-layer perceptron network and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system for forecasting precipitation based on large-scale climate signals. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2016, 61, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogardi, I.; Duckstein, L. The fuzzy logic paradigm of risk analysis. In Risk-Based Decisionmaking in Water Resources X; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2003; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- See, L.; Openshaw, S. A hybrid multi-model approach to river level forecasting. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2000, 45, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.K.; Chatterjee, C. Development of an accurate and reliable hourly flood forecasting model using wavelet–bootstrap–ANN (WBANN) hybrid approach. J. Hydrol. 2010, 394, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães Santos, C.A.; da Silva, G.B.L. Daily streamflow forecasting using a wavelet transform and artificial neural network hybrid models. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2014, 59, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supratid, S.; Aribarg, T.; Supharatid, S. An integration of stationary wavelet transform and nonlinear autoregressive neural network with exogenous input for baseline and future forecasting of reservoir inflow. Water Resour. Manag. 2017, 31, 4023–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Shamseldin, A.Y.; Melville, B.W. Comparative study of different wavelet based neural network models for rainfall–runoff modeling. J. Hydrol. 2014, 515, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubossarsky, E.; Friedman, J.H.; Ormerod, J.T.; Wand, M.P. Wavelet-based gradient boosting. Stat. Comput. 2016, 26, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partal, T. Wavelet regression and wavelet neural network models for forecasting monthly streamflow. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2017, 8, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, M.; Kisi, O. Predicting river daily flow using wavelet-artificial neural networks based on regression analyses in comparison with artificial neural networks and support vector machine models. Neural Comput. Appl. 2017, 28, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Tiwari, M.K.; Chatterjee, C.; Mishra, A. Reservoir inflow forecasting using ensemble models based on neural networks, wavelet analysis and bootstrap method. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 4863–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Kim, S.; Kisi, O.; Singh, V.P. Daily water level forecasting using wavelet decomposition and artificial intelligence techniques. J. Hydrol. 2015, 520, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhishri, S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, J.K. Comparative evaluation of neural network and regression based models to simulate runoff and sediment yield in an outer Himalayan watershed. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2016, 18, 681–694. [Google Scholar]

- Hearst, M.A.; Dumais, S.T.; Osuna, E.; Platt, J.; Scholkopf, B. Support vector machines. IEEE Intell. Syst. Their Appl. 1998, 13, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.; Mukherjee, S. Support vector method for multivariate density estimation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2000, 4, 659–665. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ma, K.; Jin, Z.; Zhu, Y. A new flood forecasting model based on SVM and boosting learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2016; pp. 1343–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani, M.; Saghafian, B.; Nasiri Saleh, F.; Farokhnia, A.; Noori, R. Uncertainty analysis of streamflow drought forecast using artificial neural networks and Monte-Carlo simulation. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibike, Y.B.; Velickov, S.; Solomatine, D.; Abbott, M.B. Model induction with support vector machines: Introduction and applications. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2001, 15, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, M.A.; Ghosh, S. Prediction of extreme rainfall event using weather pattern recognition and support vector machine classifier. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2013, 114, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, F.; Gargano, R.; de Marinis, G. Support vector regression for rainfall-runoff modeling in urban drainage: A comparison with the EPA’s storm water management model. Water 2016, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, S.; Wang, H. A comparative study of artificial neural networks, support vector machines and adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system for forecasting groundwater levels near lake okeechobee, Florida. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajarmizadeh, M.; Lafdani, E.K.; Harun, S.; Ahmadi, A. Application of SVM and swat models for monthly streamflow prediction, a case study in South of Iran. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 19, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Xiong, T.; Hu, Z. Multi-step-ahead time series prediction using multiple-output support vector regression. Neurocomputing 2014, 129, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.; Han, D. Identification of support vector machines for runoff modelling. J. Hydroinform. 2004, 6, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrany, M.S.; Pradhan, B.; Mansor, S.; Ahmad, N. Flood susceptibility assessment using GIS-based support vector machine model with different kernel types. Catena 2015, 125, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisi, O.; Parmar, K.S. Application of least square support vector machine and multivariate adaptive regression spline models in long term prediction of river water pollution. J. Hydrol. 2016, 534, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liong, S.Y.; Sivapragasam, C. Flood stage forecasting with support vector machines. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2002, 38, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachindra, D.; Huang, F.; Barton, A.; Perera, B. Least square support vector and multi-linear regression for statistically downscaling general circulation model outputs to catchment streamflows. Int. J. Climatol. 2013, 33, 1087–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De’ath, G.; Fabricius, K.E. Classification and regression trees: A powerful yet simple technique for ecological data analysis. Ecology 2000, 81, 3178–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrany, M.S.; Pradhan, B.; Jebur, M.N. Spatial prediction of flood susceptible areas using rule based decision tree (DT) and a novel ensemble bivariate and multivariate statistical models in GIS. J. Hydrol. 2013, 504, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.; Saghafian, B.; Rivaz, F.; Khodadadi, A. Evaluation of dynamic regression and artificial neural networks models for real-time hydrological drought forecasting. Arabian J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubin, B.; Zehtabian, G.; Azareh, A.; Rafiei-Sardooi, E.; Sajedi-Hosseini, F.; Kişi, Ö. Precipitation forecasting using classification and regression trees (CART) model: A comparative study of different approaches. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubin, B.; Darabi, H.; Rahmati, O.; Sajedi-Hosseini, F.; Kløve, B. River suspended sediment modelling using the cart model: A comparative study of machine learning techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomforest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Lai, C.; Chen, X.; Yang, B.; Zhao, S.; Bai, X. Flood hazard risk assessment model based on random forest. J. Hydrol. 2015, 527, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrany, M.S.; Pradhan, B.; Jebur, M.N. Flood susceptibility mapping using a novel ensemble weights-of-evidence and support vector machine models in GIS. J. Hydrol. 2014, 512, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Tuan, T.A.; Klempe, H.; Pradhan, B.; Revhaug, I. Spatial prediction models for shallow landslide hazards: A comparative assessment of the efficacy of support vector machines, artificial neural networks, kernel logistic regression, and logistic model tree. Landslides 2016, 13, 361–378. [Google Scholar]

- Etemad-Shahidi, A.; Mahjoobi, J. Comparison between m5′ model tree and neural networks for prediction of significant wave height in lake superior. Ocean Eng. 2009, 36, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietterich, T.G. Ensemble methods in machine learning. In International Workshop on Multiple Classifier Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sajedi-Hosseini, F.; Malekian, A.; Choubin, B.; Rahmati, O.; Cipullo, S.; Coulon, F.; Pradhan, B. A novel machine learning-based approach for the risk assessment of nitrate groundwater contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.J.; Kurt, M.; Eriten, M.; McFarland, D.M.; Bergman, L.A.; Vakakis, A.F. Wavelet-bounded empirical mode decomposition for measured time series analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 99, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-C.; Chau, K.-W.; Xu, D.-M.; Chen, X.-Y. Improving forecasting accuracy of annual runoff time series using ARIMA based on EEMD decomposition. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 2655–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Musaylh, M.S.; Deo, R.C.; Li, Y.; Adamowski, J.F. Two-phase particle swarm optimized-support vector regression hybrid model integrated with improved empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise for multiple-horizon electricity demand forecasting. Appl. Energy 2018, 217, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Lu, W.; Xin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Yu, T. Monthly rainfall forecasting using EEMD-SVR based on phase-space reconstruction. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 2311–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hou, G.; Ma, B.; Hua, W. Operating characteristic information extraction of flood discharge structure based on complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise and permutation entropy. J. Vib. Control 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrzadeh, H.; Sarukkalige, R.; Jayawardena, A. Hourly runoff forecasting for flood risk management: Application of various computational intelligence models. J. Hydrol. 2015, 529, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Barros, A.P. Quantitative flood forecasting using multisensor data and neural networks. J. Hydrol. 2001, 246, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafian, B.; Haghnegahdar, A.; Dehghani, M. Effect of ENSO on annual maximum floods and volume over threshold in the southwestern region of Iran. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2017, 62, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourgialas, N.N.; Dokou, Z.; Karatzas, G.P. Statistical analysis and ann modeling for predicting hydrological extremes under climate change scenarios: The example of a small Mediterranean Agro-watershed. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 154, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, R.K.; Pramanik, N.; Bala, B. Simulation of river stage using artificial neural network and mike 11 hydrodynamic model. Comput. Geosci. 2010, 36, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, R.; Karbassi, A.; Farokhnia, A.; Dehghani, M. Predicting the longitudinal dispersion coefficient using support vector machine and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system techniques. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2009, 26, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Filho, A.J.; dos Santos, C.C. Modeling a densely urbanized watershed with an artificial neural network, weather radar and telemetric data. J. Hydrol. 2006, 317, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingyi, Z.; Hall, M.J. Regional flood frequency analysis for the Gan-Ming River basin in China. J. Hydrol. 2004, 296, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Simonovic, S.P. An artificial neural network model for generating hydrograph from hydro-meteorological parameters. J. Hydrol. 2005, 315, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Q.; Yu, Z.; Hao, Z.; Ou, G.; Zhao, J.; Liu, D. Division-based rainfall-runoff simulations with BP neural networks and Xinanjiang model. Neurocomputing 2009, 72, 2873–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, G.B.; Ray, C.; De Carlo, E.H. Use of neural network to predict flash flood and attendant water qualities of a mountainous stream on Oahu, Hawaii. J. Hydrol. 2006, 327, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, D.K. Measuring Discharge Using Back-Propagation Neural Network: A Case Study on Brahmani River Basin; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 591–598. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.-X.; Cheng, G.-J.; Cai, L. Comparison of the extreme learning machine with the support vector machine for reservoir permeability prediction. Comput. Eng. Sci. 2010, 2, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, F.-J.; Chen, P.-A.; Lu, Y.-R.; Huang, E.; Chang, K.-Y. Real-time multi-step-ahead water level forecasting by recurrent neural networks for urban flood control. J. Hydrol. 2014, 517, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.-Y.; Chang, L.-C. Online multistep-ahead inundation depth forecasts by recurrent NARX networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruen, M.; Yang, J. Functional networks in real-time flood forecasting—A novel application. Adv. Water Resour. 2005, 28, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.-M.; Chang, F.-J.; Jou, B.J.-D.; Lin, P.-F. Dynamic ANN for precipitation estimation and forecasting from radar observations. J. Hydrol. 2007, 334, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, B.; Solomatine, D.P. Neural networks and M5 model trees in modelling water level-discharge relationship. Neurocomputing 2005, 63, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiser, M.; Scheidl, C.; Eisl, J.; Spangl, B.; Hübl, J. Process type identification in torrential catchments in the eastern Alps. Geomorphology 2015, 232, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Pham, B.T.; Chapi, K.; Shirzadi, A.; Shahabi, H.; Revhaug, I.; Prakash, I.; Bui, D.T. A comparative assessment of decision trees algorithms for flash flood susceptibility modeling at haraz watershed, Northern Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aichouri, I.; Hani, A.; Bougherira, N.; Djabri, L.; Chaffai, H.; Lallahem, S. River flow model using artificial neural networks. Energy Procedia 2015, 74, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, M.; Hashemi, S.; Saybani, M.R.; Shamshirband, S.; Mosavi, A. A Hybrid clustering and classification technique for forecasting short-term energy consumption. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2018, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowski, J.F. Development of a short-term river flood forecasting method for snowmelt driven floods based on wavelet and cross-wavelet analysis. J. Hydrol. 2008, 353, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, P.; Kiely, G.; Corcoran, G. Structural optimisation and input selection of an artificial neural network for river level prediction. J. Hydrol. 2008, 355, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.C. Soft computing techniques in ensemble precipitation nowcast. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 2013, 13, 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Schiffer, R.A.; Rossow, W.B. The International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project (ISCCP): The first project of the world climate research programme. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1983, 64, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, E. Functional networks. Neural Process. Lett. 1998, 7, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimeno-Sáez, P.; Senent-Aparicio, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, J.; Pulido-Velazquez, D.; Cecilia, J.M. Estimation of instantaneous peak flow using machine-learning models and empirical formula in peninsular Spain. Water 2017, 9, 347. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, F.-J.; Chang, Y.-T. Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system for prediction of water level in reservoir. Adv. Water Resour. 2006, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, A.; Lopez, A.; Varkonyi-Koczy, A.R. Industrial Applications of Big Data: State of the Art Survey. In Recent Advances in Technology Research and Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaeianzadeh, M.; Tabari, H.; Yazdi, A.A.; Isik, S.; Kalin, L. Flood flow forecasting using ANN, ANFIS and regression models. Neural Comput. Appl. 2014, 25, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrany, M.S.; Pradhan, B.; Jebur, M.N. Flood susceptibility analysis and its verification using a novel ensemble support vector machine and frequency ratio method. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2015, 29, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.C.; Liu, W.C.; Wu, M.C. A physically based and machine learning hybrid approach for accurate rainfall-runoff modeling during extreme typhoon events. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 2017, 53, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunkaynak, A.; Nigussie, T.A. Prediction of daily rainfall by a hybrid wavelet-season-neuro technique. J. Hydrol. 2015, 529, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-C.; Shen, H.-Y.; Chang, F.-J. Regional flood inundation nowcast using hybrid SOM and dynamic neural networks. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, T.; Sahoo, B.; Beria, H.; Chatterjee, C. A wavelet-based non-linear autoregressive with exogenous inputs (WNARX) dynamic neural network model for real-time flood forecasting using satellite-based rainfall products. J. Hydrol. 2016, 539, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.; Mawdsley, R.; Fujiyama, T.; Achuthan, K. Combining machine learning with computational hydrodynamics for prediction of tidal surge inundation at estuarine ports. Procedia IUTAM 2017, 25, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.-C. Rainfall forecasting by technological machine learning models. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008, 200, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.-Y.; Yang, Y.-T.; Kuo, H.-C.; Tan, Y.-C.; Lai, J.-S.; Chang, T.-J.; Lee, C.-S.; Hsu, K.H. Improvement of watershed flood forecasting by typhoon rainfall climate model with an ANN-based southwest monsoon rainfall enhancement. J. Hydrol. 2013, 506, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajurkar, M.; Kothyari, U.; Chaube, U. Modeling of the daily rainfall-runoff relationship with artificial neural network. J. Hydrol. 2004, 285, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Lin, S.-H.; Fu, J.-C.; Chung, S.-F.; Chen, A.S. Longitudinal stage profiles forecasting in rivers for flash floods. J. Hydrol. 2010, 388, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Guo, S.; Xiong, L.; Li, C. A nonlinear perturbation model based on artificial neural network. J. Hydrol. 2007, 333, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doycheva, K.; Horn, G.; Koch, C.; Schumann, A.; König, M. Assessment and weighting of meteorological ensemble forecast members based on supervised machine learning with application to runoff simulations and flood warning. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 33, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.W.; Bourdin, D.R.; Campbell, D.; Stull, R.B.; Gardner, T. Development and operational testing of a super-ensemble artificial intelligence flood-forecast model for a pacific northwest river. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2015, 51, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubin, B.; Khalighi, S.S.; Malekian, A. Impacts of Large-Scale Climate Signals on Seasonal Rainfall in the Maharlu-Bakhtegan Watershed; Journal of Range and Watershed Management: Kashan, Iran, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kisi, O.; Sanikhani, H. Prediction of long-term monthly precipitation using several soft computing methods without climatic data. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 4139–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, J. A data-driven SVR model for long-term runoff prediction and uncertainty analysis based on the Bayesian framework. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 133, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Coulibaly, P. Bayesian flood forecasting methods: A review. J. Hydrol. 2017, 551, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubin, B.; Moradi, E.; Golshan, M.; Adamowski, J.; Sajedi-Hosseini, F.; Mosavi, A. An Ensemble prediction of flood susceptibility using multivariate discriminant analysis, classification and regression trees, and support vector machines. Elsevier Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 651, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, J.; Jakeman, A.; Vaze, J.; Croke, B.F.; Dutta, D.; Kim, S. Flood inundation modelling: A review of methods, recent advances and uncertainty analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 90, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsafi, S.H. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) for flood forecasting at Dongola station in the river Nile, Sudan. Alex. Eng. J. 2014, 53, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, D.; Bazaz, J.B.; Yazd, S.V.J.; Alavi, A.H. Deriving an intelligent model for soil compression index utilizing multi-gene genetic programming. Springer Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Borah, B. Indian summer monsoon rainfall prediction using artificial neural network. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2013, 27, 1585–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, M.A.; Hassan, M.; Ahmad, S.; Zeeshan, M. A comparison of artificial neural networks (ANN) and local linear regression (LLR) techniques for predicting monthly reservoir levels. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeian-Zadeh, M.; Tabari, H.; Abghari, H. Prediction of monthly discharge volume by different artificial neural network algorithms in semi-arid regions. Arabian J. Geosci. 2013, 6, 2529–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazendam, E.; Gharabaghi, B.; Ackerman, J.D.; Whiteley, H. Integrative neural networks models for stream assessment in restoration projects. J. Hydrol. 2016, 536, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-Y.; Cheng, C.-T.; Chau, K.-W. Using support vector machines for long-term discharge prediction. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2006, 51, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.C.; Griffioen, P.; White, M.D.; Nally, R.M. Assessment of ecosystems: A system for rigorous and rapid mapping of floodplain forest condition for Australia’s most important river. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Kalra, A.; Stephen, H. Estimating soil moisture using remote sensing data: A machine learning approach. Adv. Water Resour. 2010, 33, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.D.; Ravinesh, C.; Li, Y.; Maraseni, T. Input selection and performance optimization of ANN-based streamflow forecasts in the drought-prone murray darling basin region using IIS and MODWT algorithm. Atmos. Res. 2017, 197, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, B.; Fanni, A.; Sias, G.; Tronci, S.; Zedda, M.K. River flow forecasting using neural networks and wavelet analysis. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2005, 7, 08651. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, B. An Intelligent Artificial Neural Network-Response Surface Methodology Method for Accessing the Optimum Biodiesel and Diesel Fuel Blending Conditions in a Diesel Engine from the Viewpoint of Exergy and Energy Analysis. Energies 2018, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.M. Wavelet-ANN model for flood events. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Soft Computing for Problem Solving (SocProS 2011), Patiala, India, 20–22 December 2011; pp. 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ramana, R.V.; Krishna, B.; Kumar, S.R.; Pandey, N.G. Monthly rainfall prediction using wavelet neural network analysis. Water Resour. Manag. 2013, 27, 3697–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantanee, S.; Patamatammakul, S.; Oki, T.; Sriboonlue, V.; Prempree, T. Coupled wavelet-autoregressive model for annual rainfall prediction. J. Environ. Hydrol. 2005, 13, 124–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mekanik, F.; Imteaz, M.A.; Talei, A. Seasonal rainfall forecasting by adaptive network-based fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) using large scale climate signals. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 46, 3097–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Chau, K.W.; Cheng, C.T.; Qiu, L. A comparison of performance of several artificial intelligence methods for forecasting monthly discharge time series. J. Hydrol. 2009, 374, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisi, O.; Nia, A.M.; Gosheh, M.G.; Tajabadi, M.R.J.; Ahmadi, A. Intermittent streamflow forecasting by using several data driven techniques. Water Resour. Manag. 2012, 26, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, S.; Zhang, J. Modified NLPM-ANN model and its application. J. Hydrol. 2009, 378, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chang, J.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y. Monthly streamflow prediction using modified EMD-based support vector machine. J. Hydrol. 2014, 511, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhou, J.; Ye, L.; Meng, C. Streamflow estimation by support vector machine coupled with different methods of time series decomposition in the upper reaches of Yangtze River, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.; Bedient, P. Surrogate modeling of joint flood risk across coastal watersheds. J. Hydrol. 2018, 558, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araghinejad, S.; Azmi, M.; Kholghi, M. Application of artificial neural network ensembles in probabilistic hydrological forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2011, 407, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.-F.; Lei, X.-H.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wen, X.; Ji, Y.; Kang, A.-Q. An adaptive middle and long-term runoff forecast model using EEMD-ANN hybrid approach. J. Hydrol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A. Sustainable Business Model: A Review. Preprints 2018, 2018100378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høverstad, B.A.; Tidemann, A.; Langseth, H.; Öztürk, P. Short-term load forecasting with seasonal decomposition using evolution for parameter tuning. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 6, 1904–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantithamthavorn, C.; McIntosh, S.; Hassan, A.E.; Matsumoto, K. Automated parameter optimization of classification techniques for defect prediction models. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACM 38th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Austin, TX, USA, 14–22 May 2016; pp. 321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Varkonyi-Koczy, A.R. Review on the usage of the multiobjective optimization package of modefrontier in the energy sector. In Recent Advances in Technology Research and Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Dineva, A.; Várkonyi-Kóczy, A.R.; Tar, J.K. Anytime fuzzy supervisory system for signal auto-healing. In Advanced Materials Research; Trans Tech Publications: Tihany, Hungary, 2015; pp. 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, M.; Mosavi, A.; Ozturk, P.; Varkonyi-Koczy, A.; Istvan, V. A hybrid machine learning approach for daily prediction of solar radiation. In Recent Advances in Technology Research and Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Solgi, A.; Nourani, V.; Pourhaghi, A. Forecasting daily precipitation using hybrid model of wavelet-artificial neural network and comparison with adaptive neurofuzzy inference system (case study: Verayneh station, Nahavand). Adv. Civ. Eng. 2014, 2014, 279368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrzadeh, H.; Sarukkalige, R.; Jayawardena, A. Improving ann-based short-term and long-term seasonal river flow forecasting with signal processing techniques. River Res. Appl. 2016, 32, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modeling Technique | Reference | Flood Resource Variable | Prediction Type | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN vs. statistical | [1] | Streamflow and flash food | Hourly | USA |

| ANN vs. traditional | [44] | Water and surge level | Hourly | Japan |

| ANN vs. statistical | [149] | Flood | Real-time | UK |

| ANN vs. statistical | [150] | Extreme flow | Hourly | Greece |

| FFANN vs. ANN | [151] | Water level | Hourly | India |

| ANN vs. T–S | [4] | Flood | Hourly | India |

| ANN vs. AR | [153] | Stage level and streamflow | Hourly | Brazil |

| MLP vs. Kohonen NN | [154] | Flood frequency analysis | Long-term | China |

| BPANN | [155] | Peak flow of flood | Daily | Canada |

| BPANN vs. DBPANN | [156] | Rainfall–runoff | Monthly and daily | China |

| BPANN | [157] | Flash flood | Real-time | Hawaii |

| BPANN | [158] | Runoff | Daily | India |

| ELM vs. SVM | [159] | Streamflow | Daily | China |

| BPANN vs. NARX | [160,161] | Urban flood | Real-time | Taiwan |

| FFANN vs. Functional ANN | [162] | River flows | Real-time | Ireland |

| Recurrent NN vs. Z–R relation | [163] | Rainfall prediction | Real-time | Taiwan |

| ANN vs. M5 model tree | [164] | Peak flow | Hourly | India |

| NBT vs. DT vs. Multinomial regression | [165] | Flash flood | Real-time, hourly | Austria |

| DTs vs. NBT vs. ADT vs. LMT, and REPT | [166] | Flood | Hourly/daily | Iran |

| MLP vs. MLR | [167,168] | River flow and rainfall–runoff | Daily | Algeria |

| MLP vs. MLR | [98] | River runoff | Hourly | Morocco |

| MLP vs. WT vs. MLR vs. ANN | [169] | River flood forecasting | Daily | Canada |

| ANN vs. MLP | [170] | River level | Hourly | Ireland |

| MLP vs. DT vs. CART vs. CHAID | [171] | Flood during typhoon | Rainfall–runoff | China |

| SVM vs. ANN | [120] | Rainfall extreme events | Daily | India |

| ANN vs. SVR | [48] | Flood | Daily | Canada |

| RF vs. SVM | [69] | Rainfall | Hourly | Taiwan |

| Modeling Technique | Complexity of Algorithm | Ease of Use | Speed | Accuracy | Input Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN | High | Low | Fair | Fair | Historical |

| BPANN | Fairly high | Low | Fairly high | Fairly high | Historical |

| MLP | Fairly high | Fair | High | Fairly high | Historical |

| ELM | Fair | Fairly high | Fairly high | Fair | Historical |

| CART | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fairly high | Historical |

| SVM | Fairly high | Low | Low | Fair | Historical |

| ANFIS | Fair | Fairly high | Fair | Fairly high | Historical |

| Modeling Technique | Reference | Flood resource Variable | Prediction Type | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANFIS vs. ANN | [174] | Flash floods | Real-time | Spain |

| ANFIS vs. ANN | [175,176] | Water level | Hourly | Taiwan |

| ANFIS vs. ANN | [46] | Watershed rainfall | Hourly | Taiwan |

| ANFIS vs. ANN | [67] | Flood quantiles | Real-time | Canada |

| ANN vs. ANFIS | [177] | Daily flow | Daily | Iran |

| CART vs. ANFIS vs. MLP vs. SVM | [134] | Sediment transport | Daily | Iran |

| MLP vs. GRNNM vs. NNM | [96] | Flood prediction | Daily | Korea |

| SVM-FR vs. DT | [178] | Rainfall–runoff | Real-time | Malaysia |

| HEC–HMS–ANN vs. HEC–HMS-SVR | [179] | Rainfall–runoff | Hourly | Taiwan |

| SAS–MP vs. W-SAS–MP | [180] | Flash flood and streamflow | Daily | Turkey |

| SOM–R-NARX vs. R-NARX | [181] | Regional flood | Hourly | Taiwan |

| Wavelet-based NARX vs. ANN, vs. WANN | [182] | Streamflow forecasting | Daily | India |

| WBANN vs. WANN vs. ANN vs. BANN | [105] | Flood | Hourly | India |

| ANN–hydrodynamic model | [183] | Flood prediction: tidal surge | Hourly | UK |

| RNN–SVR, RSVRCPSO | [184] | Flash flood: rainfall forecasting | Hourly | Taiwan |

| AME and SSNN vs. ANN | [185] | Rainfall forecasting | Hourly | Taiwan |

| Hybrid of FFNN with linear model | [186] | Flood forecasting: daily flows | Daily | India |

| FFNN vs. FBNN vs. FFRM–ANN | [187] | Flash floods | Hourly | Taiwan |

| ANN–NLPM vs. ANN | [188] | Rainfall–runoff | Daily | China |

| EPS of MLP vs. SVM vs. RF | [189] | Runoff simulations | Real-time | Germany |

| EPS of ANNs | [190] | Flood | Daily | Canada |

| Modeling Technique | Reference | Flood Resource Variable | Prediction Type | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANNs | [197] | Water levels | Seasonal | Sudan |

| ANNs | [87] | Precipitation | Monthly | Australia |

| BPNNs | [199] | Heavy rainfall | Seasonal | India |

| BPNNs vs. BFGSNN | [200] | Reservoir levels | Monthly | Turkey |

| BPNN vs. MLP | [201] | Discharge | Monthly | Iran |

| ANNs vs. HBI | [202] | Stream | Weekly | Canada |

| SVM vs. ANN | [203] | Streamflow | Monthly | China |

| RT | [204] | Floodplain forests | Annually | Australia |

| Modeling Technique | Complexity of Algorithm | Ease of Use | Speed | Accuracy | Input Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN | Fairly high | Low | Fair | High | Historical |

| BPNN | Fairly high | Low | Fairly high | Fairly high | Historical |

| MLP | high | Fair | High | Fairly high | Historical |

| SVR | Fairly high | Low | Low | High | Historical |

| RT | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fairly high | Historical |

| SVM | Fairly high | Low | Low | High | Historical |

| M5 tree | Fair | Low | Fair | Fair | Historical |

| Modeling Technique | Reference | Flood Resource Variable | Prediction Type | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoregressive ANN vs. ARMA vs. ARIMA | [26] | River inflow | Monthly and yearly | Iran |

| Hybrid WNN vs. M5 model tree | [206] | Streamflow water level | Monthly | Australia |

| WNN vs. ANN | [207,208] | Rainfall–runoff | Monthly | Italy |

| WNN-BB vs. WNN vs. ANN | [50] | Streamflow | Weekly and few days | Canada |

| WNN vs. ANN | [25] | Urban water | Monthly | Canada |

| WNN vs. ANN | [209] | Peak flows | Seasonal | India |

| WNN vs. ANN | [210] | Rainfall | Monthly | India |

| WARM vs. AR | [211] | Rainfall | Yearly | Thailand |

| ANFIS vs. ANNs | [212] | Rainfall | Seasonal | Australia |

| ANFIS vs. ARMA vs. ANNs vs. SVM | [213] | Discharge | Monthly | China |

| ANFIS, ANNs vs. SVM vs. LLR | [214] | Streamflow | Short-term | Turkey |

| NLPM–ANN | [215] | Flood forecasting | Yearly | China |

| M-EMDSVM vs. ANN vs. SVM | [216] | Streamflow | Monthly | China |

| SVR–DWT–EMD | [217] | Streamflow | Monthly | China |

| Surrogate modeling–ML vs. ANN–Kriging model vs. ANN–PCA | [218] | Rainfall–runoff | Yearly | USA |

| EPS of ANNs: K-NN vs. MLP vs. MLP–PLC vs. ANNE | [219] | Streamflow | Seasonal | Canada |

| EEMD–ANN vs. SVM vs. ANFIS | [220] | Runoff forecast | Monthly | China |

| WNN vs. ANN vs. WLGP | [51] | Streamflow | Monthly | Iran |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mosavi, A.; Ozturk, P.; Chau, K.-w. Flood Prediction Using Machine Learning Models: Literature Review. Water 2018, 10, 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111536

Mosavi A, Ozturk P, Chau K-w. Flood Prediction Using Machine Learning Models: Literature Review. Water. 2018; 10(11):1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111536

Chicago/Turabian StyleMosavi, Amir, Pinar Ozturk, and Kwok-wing Chau. 2018. "Flood Prediction Using Machine Learning Models: Literature Review" Water 10, no. 11: 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111536

APA StyleMosavi, A., Ozturk, P., & Chau, K.-w. (2018). Flood Prediction Using Machine Learning Models: Literature Review. Water, 10(11), 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111536