Stratospheric Polar Vortex as an Important Link between the Lower Atmosphere Circulation and Solar Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Polar Vortex as a Possible Reason for Temporal Variability of Solar–Atmospheric Links

2.1. Polar Vortex and Its Role in Atmospheric Processes

2.2. Temporal Variability of Solar Activity Effects on the Lower Atmosphere Characteristics: Previous Data

2.3. Spatial and Temporal Variability in Galactic Cosmic Ray Effects on Troposphere Pressure

2.4. Temporal Variability of Solar Activity Effects on Troposphere Pressure in the Northern Hemisphere and the Epochs of Large-Scale Circulation

2.5. Evolution of the Polar Vortex as a Possible Reason for Temporal Variability in Solar Activity Effects on the Lower Atmosphere Circulation

2.6. Destruction of Cloud-GCR Correlation: Possible Role of the Vortex Weakening

3. Solar Activity Influences of the Polar Vortex State

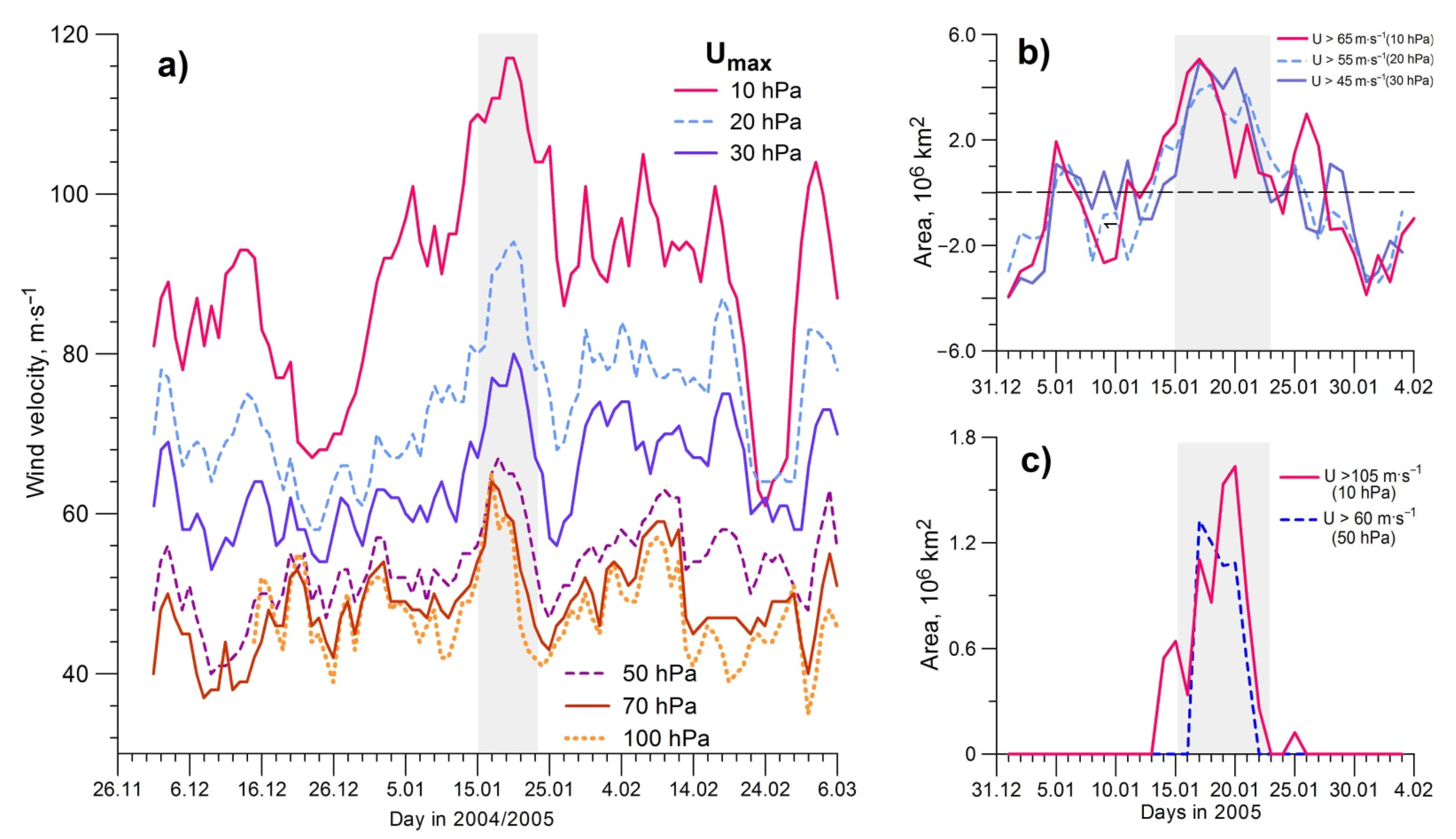

3.1. Vortex Intensification Associated with Solar Proton Events

3.2. Possible Factors of the Vortex Intensification on the Multidecadal Time Scale

3.3. Possible Mechanisms of Solar Activity Effects on the Polar Vortex Intensity

4. Conclusions

- Temporal variability of solar activity phenomena on the circulation of the lower atmosphere reveals a roughly 60-year periodicity that seems to be associated with changes in the epochs of large-scale circulation. The reversals of correlation links between troposphere pressure variations at extratropical latitudes (development of extratropical baric systems) and solar activity phenomena were found to coincide with the turning points in the evolution of the main forms of atmospheric circulation according to the Vangengeim–Girs classification.

- In turn, changes in the circulation epochs seem to be related to the transitions between the different states of the stratospheric polar vortex. As follows from the analysis of the stratospheric data and sea level pressure/temperature oscillations at polar latitudes, the intensity of the vortex undergoes oscillations with a period close to 60 years. Under a strong vortex, increases in GCR fluxes contribute to the intensification of extratropical cyclones, whereas under a weak vortex, the effects change the sign. The intensification of extratropical cyclogenesis associated with GCR increases under a strong vortex regime resulted in a high positive correlation between cloudiness and GCR intensity in ~1980–2000. A sharp weakening of the vortex near 2000 seems to be a possible reason for the destruction of this correlation. The obtained results show that the stratospheric polar vortex plays an important part in the mechanism of solar–atmospheric links, which seems to be due to its capability to affect troposphere–stratosphere interaction via planetary waves.

- The state of the polar vortex may be affected by different solar activity phenomena contributing to a roughly 60-year oscillation of its intensity. A high-latitudinal location of the vortex is favorable for the effects of ionization increases associated with charged particle fluxes (solar and galactic cosmic rays as well as auroral and radiation belt electrons). The ionization increases result in changes in the chemical composition (ozone depletion), influencing the temperature regime of the polar atmosphere, as well as conductivity increases, influencing the vertical electric currents and microphysical processes in clouds.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Girs, A.A. Macro-Circulation Method of Long-Term Meteorological Forecasts; Gidrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kanamitsu, M.; Ebisuzaki, W.; Woollen, J.; Yang, S.-K.; Hnilo, J.; Fiorino, M.; Potter, G.L. NCEP-DOE AMIP-II Reanalysis (R-2). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2002, 83, 1631–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnay, E.; Kanamitsu, M.; Kistler, R.; Collins, W.; Deaven, D.; Gandin, L.; Iredell, M.; Saha, S.; White, G.; Woolen, G.; et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1996, 77, 437–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S. Progress towards a quantitative understanding of Antarctic ozone depletion. Nature 1990, 347, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.P.; Dunkerton, T.J. Stratospheric harbingers of anomalous weather regimes. Science 2001, 294, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkovich, Z.M.; Karklin, V.P.; Smolyanitsky, V.M.; Frolov, I.E. On the character and causes of the Earth’s climate change. Probl. Arctic Antarct. 2009, 81, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Labitzke, K. Sunspots, the QBO, and the stratospheric temperature in the north-pole region. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1987, 4, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, J.R.; Tan, H.C. The influence of the equatorial quasi-biennial oscillation on the global circulation at 50 mb. J. Atmos. Sci. 1980, 37, 2200–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köppen, W. On temperature cycles. Nature 1873, 9, 184–185. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, J.R.; Goldberg, R.A. Sun, Weather and Climate; NASA Scientific and Technical Information Branch: Washington, DC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Santillán, N.; Esquivel Herrera, A.; Sánchez-Trejo, R. Evidences for a shift in barometric pressure, air temperature and rainfall pattern circa 1920 and its possible relation to solar activity. Hidrobiologica 2002, 12, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva, K.; Kirov, B.; Tonev, P.; Guineva, V.; Atanasov, D. Long-term variations in the correlation between NAO and solar activity: The importance of north-south solar activity asymmetry for atmospheric circulation. Adv. Space Res. 2007, 40, 1152–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thejll, P.; Christiansen, B.; Gleisner, H. On correlations between the North Atlantic Oscillation, geopotential heights, and geomagnetic activity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukianova, R.; Alekseev, G. Long-term correlation between the NAO and solar activity. Sol. Phys. 2004, 224, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, K.; Kirov, B.; Koucká-Knížová, P.; Mošna, Z.; Kouba, D.; Asenovska, Y. Solar influences on atmospheric circulation. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2012, 90–91, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, N.; Svensmark, H. Low cloud properties influenced by cosmic rays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 5004–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ney, E.P. Cosmic radiation and weather. Nature 1959, 183, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudovkin, M.I.; Raspopov, O.M. The mechanism of action of solar activity on the state of lower atmosphere and meteorological parameters. Geomagn. Aeron. 1992, 32, 593–608. [Google Scholar]

- Miroshnichenko, L.I. Solar cosmic rays in the system of solar–terrestrial relations. J. Atm. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2008, 70, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, B.A. The global atmospheric electric circuit and its effects on cloud microphysics. Rep. Progr. Phys. 2008, 71, 66801–66900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazilevskaya, G.A.; Usoskin, I.G.; Flückiger, E.O.; Harrison, R.G.; Desorgher, L.; ·Bütikofer, R.; Krainev, M.B.; Makhmutov, V.S.; ·Stozhkov, Y.I.; Svirzhevskaya, A.K.; et al. Cosmic Ray Induced Ion Production in the Atmosphere. Space Sci. Rev. 2008, 137, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.; Thejll, P. Effects of energetic Solar Proton Events on the cyclone development in the North Atlantic. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2004, 66, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.; Thejll, P. Cyclone regeneration in the North Atlantic intensified by energetic solar proton events. Adv. Space Res. 2005, 35, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artamonova, I.; Veretenenko, S. Galactic cosmic ray variation influence on baric system dynamics at middle latitudes. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2011, 73, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.; Ogurtsov, M. Regional and temporal variability of solar activity and galactic cosmic ray effects on the lower atmosphere circulation. Adv. Space Res. 2012, 49, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.; Ogurtsov, M. Stratospheric polar vortex as a possible reason for temporal variations of solar activity and galactic cosmic ray effects on the lower atmosphere circulation. Adv. Space Res. 2014, 54, 2467–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebisuzaki, W. A method to estimate the statistical significance of a correlation when the data are serially correlated. J. Clim. 1997, 10, 2147–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromov, S.P.; Petrociants, M.A. Meteorology and Climatology; Moscow University Press: Moscow, Russia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Clette, F.; Lefèvre, L. The new sunspot number: Assembling all corrections. Sol. Phys. 2016, 291, 2629–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.; Ogurtsov, M. Manifestation and possible reasons of ~60-year oscillations in solar-atmospheric links. Adv. Space Res. 2019, 64, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangengeim, G.Y. Principles of the macro-circulation methods of long-term meteorological forecasts for the Arctic. Tr. AANII 1952, 34, 11–66. [Google Scholar]

- Girs, A.A. About the creation of a unified classification of the macrosynoptic processes in the Northern hemisphere. Meteorol. I Gidrol. 1964, 4, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bolotinskaya, M.S.; Ryzhakov, L.Y. Catalogue of Macrosynoptic Processes According to Vangengeim Classification 1891–1962; Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute: Leningrad, Russia, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Stozhkov, Y.I.; Svirzhevsky, N.S.; Bazilevskaya, G.A.; Kvashnin, A.N.; Makhmutov, V.S.; Svirzhevskaya, A.K. Long-term (50 years) measurements of cosmic ray fluxes in the atmosphere. Adv. Space Res. 2009, 44, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Compo, G.P. A practical guide to wavelet analyses. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998, 79, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlwitz, J.; Graf, H.-F. Troposphere-stratosphere dynamic coupling under strong and weak polar vortex conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdyushin, S.I.; Danilov, A.D. The Sun, weather, and climate: A present-day view of the problem (review). Geomagn. Aeron. 2000, 40, 545–555. [Google Scholar]

- Pudovkin, M.I.; Veretenenko, S.V. Cloudiness decreases associated with Forbush-decreases of galactic cosmic rays. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 1995, 57, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensmark, H.; Friis-Christensen, E. Variations of cosmic ray flux and global cloud coverage – a missing link in solar–climate relationships. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 1997, 59, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlykin, A.D.; Wolfendale, A.W. Cosmic ray effects on cloud cover and their relevance to climate change. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2011, 73, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.; Ogurtsov, M. Cloud cover anomalies at middle latitudes: Links to troposphere dynamics and solar variability. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2016, 149, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.; Ogurtsov, M.; Lindholm, M.; Jalkanen, R. Galactic cosmic rays and low clouds: Possible reasons for correlation reversal. In Cosmic Rays; Szadkowski, Z., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018; pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Matveev, L.T. Physics of Atmosphere; Gidrometeoizdat: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vorobjev, V.I. Synoptic Meteorology; Gidrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Carslaw, K.S.; Harrison, R.G.; Kirkby, J. Cosmic rays, clouds and climate. Science 2002, 298, 1732–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivolutsky, A.A.; Repnev, A.I. Cosmic Influences on the Ozonosphere of the Earth; GEOS: Moscow, Russia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Veretenenko, S.V.; Ogurtsov, M.G. Influence of solar-geophysical factors on the state of the stratospheric polar vortex. Geomagn. Aeron. 2020, 60, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S. Effects of Solar Proton Events of January 2005 on the middle atmosphere dynamics in the Northern hemisphere. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.V. Effects of energetic Solar Proton Events of solar cycle 23 on intensity of the stratospheric polar vortex. Geomagn. Aeron. 2021, 61, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.; Ogurtsov, M.; Obridko, V. Long-term variability in occurrence frequencies of magnetic storms with sudden and gradual commencements. J. Atm. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2020, 205, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurutani, B.T.; Gonzalez, W.D.; Gonzalez, A.L.C.; Guarnieri, F.L.; Gopalswamy, N.; Grande, M.; Kamide, Y.; Kasahara, Y.; Lu, G.; Mann, I.; et al. Corotating solar wind streams and recurrent geomagnetic activity: A review. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, A07S01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretenenko, S.V.; Ogurtsov, M.G.; Obridko, V.N.; Tlatov, A.G. Long-Term Variations in Coronal Hole Areas and Occurrence of Magnetic Storms with Gradual Commencements. Geomagn. Aeron. 2021, 61, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, D.V.; Shatten, K.H. A discussion of plausible solar irradiance variations, 1700–1992. J. Geophys. Res. 1993, 98, 18895–18906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scafetta, N.; Willson, R.C. ACRIM total solar irradiance satellite composite validation versus TSI proxy models. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2014, 350, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, D.W.; Gerard, J.-C.; Solomon, S.; Crutzen, P.J.; Reid, G.C. The effect of particle precipitation events on the neutral and ion chemistry of the middle atmosphere I. Odd nitrogen. Planet Space Sci. 1981, 29, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Rusch, D.W.; Gerard, J.-C.; Reid, G.C.; Crutzen, P.J. The effect of particle precipitation events on the neutral and ion chemistry of the middle atmosphere: II. Odd hydrogen. Planet Space Sci. 1981, 29, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasseur, G.P.; Solomon, S. Aeronomy of the Middle Atmosphere; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, L.H.; Cuikay, R.S.; Corbin, J.R. Ozone measurements in the mesosphere during the solar proton event of 2 November 1969. J. Atmos. Sci. 1972, 29, 1138–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, D.F.; Kruger, A.J.; Crutzen, P.J. Solar proton event: Influence on stratospheric ozone. Science 1977, 197, 886–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadorozhny, A.M.; Kiktenko, V.N.; Kokin, G.A.; Tuchkov, G.A.; Tyutin, A.A.; Chizhov, A.F.; Shtrikov, O.V. Middle atmosphere response to the solar proton events of October 1989 using the results of rocket measurements. J. Geophys. Res. 1994, 99, 21059–21069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, C.H.; McPeters, R.D.; Labow, G.J.; Fleming, E.L. Northern Hemisphere atmospheric effects due to the July 2000 solar proton event. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 2883–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppälä, A.; Verronen, P.T.; Kyrölä, E.; Hassinen, S.; Backman, L.; Hauchecorne, A.; Bertaux, J.L.; Fussen, D.E. Solar proton events of October-November 2003: Ozone depletion in the Northern hemisphere polar winter as seen by GOMOS/ENVISAT. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L19107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, C.H.; Marsh, D.R.; Vitt, F.M.; Roble, R.G.; Randall, C.E.; Bernath, P.F.; Funke, B.; López-Puertas, M.; Versick, S.; Stiller, G.P.; et al. Northern Hemisphere atmospheric influence of the solar proton events and ground level enhancement in January 2005. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 6153–6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivolutsky, A.A.; Klyuchnikova, A.V.; Zakharov, G.R.; Vyushkova, T.Y.; Kuminov, A.A. Dynamical response of the middle atmosphere to solar proton event of July 2000: Three-dimensional model simulations. Adv. Space Res. 2006, 37, 1602–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.N.; Mason, G.M.; Mazur, J.E. A small spacecraft mission with large accomplishments. Eos 2012, 93, 325–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, C.H. Effects of energetic particles on minor constituents of the middle atmosphere. J. Geomagn. Geoelectr. 1991, 43 (Suppl. S2), 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgaertner, A.J.G.; Seppälä, A.; Jöckel, P.; Clilverd, M.A. Geomagnetic activity related NOx enhancements and polar surface air temperature variability in a chemistry climate model: Modulation of the NAM index. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 4521–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanov, E.; Calisto, M.; Egorova, T.; Peter, T.; Schmutz, W. Influence of the precipitating energetic particles on atmospheric chemistry and climate. Surv. Geophys. 2012, 33, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Holzworth, R.H. Observations and parameterization of the stratospheric electrical conductivity. J. Geophys. Res. 1996, 101, 29539–29552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markson, R.; Muir, M. Solar wind control of the Earth’s electric field. Science 1980, 208, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzworth, R.H.; Norville, K.W.; Williamson, P.R. Solar flare perturbations in stratospheric current systems. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1987, 14, 852–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, B.A. Uncertainties in evaluating global electric circuit interactions with atmospheric clouds and aerosols, and consequences for radiation and dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. 2022, 127, e2021JD035954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, J.E.; Tinsley, B.A. The response of longwave radiation at the South Pole to electrical and magnetic variations: Links to meteorological generators and the solar wind. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2018, 179, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, J.E.; Tinsley, B.A.; Zhou, L. Relationships between the solar wind magnetic field and ground-level longwave irradiance at high northern latitudes. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2019, 193, 105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Veretenenko, S. Stratospheric Polar Vortex as an Important Link between the Lower Atmosphere Circulation and Solar Activity. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13071132

Veretenenko S. Stratospheric Polar Vortex as an Important Link between the Lower Atmosphere Circulation and Solar Activity. Atmosphere. 2022; 13(7):1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13071132

Chicago/Turabian StyleVeretenenko, Svetlana. 2022. "Stratospheric Polar Vortex as an Important Link between the Lower Atmosphere Circulation and Solar Activity" Atmosphere 13, no. 7: 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13071132

APA StyleVeretenenko, S. (2022). Stratospheric Polar Vortex as an Important Link between the Lower Atmosphere Circulation and Solar Activity. Atmosphere, 13(7), 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13071132