Genetics and Epigenetics of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Genomics

2.1. Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

2.2. Copy Number Variant (CNV) Studies

2.3. Rare Variants from Whole Exome and Whole Genome Sequencing (WES, WGS)

3. Epigenomics

3.1. Methylation

3.2. MicroRNAs

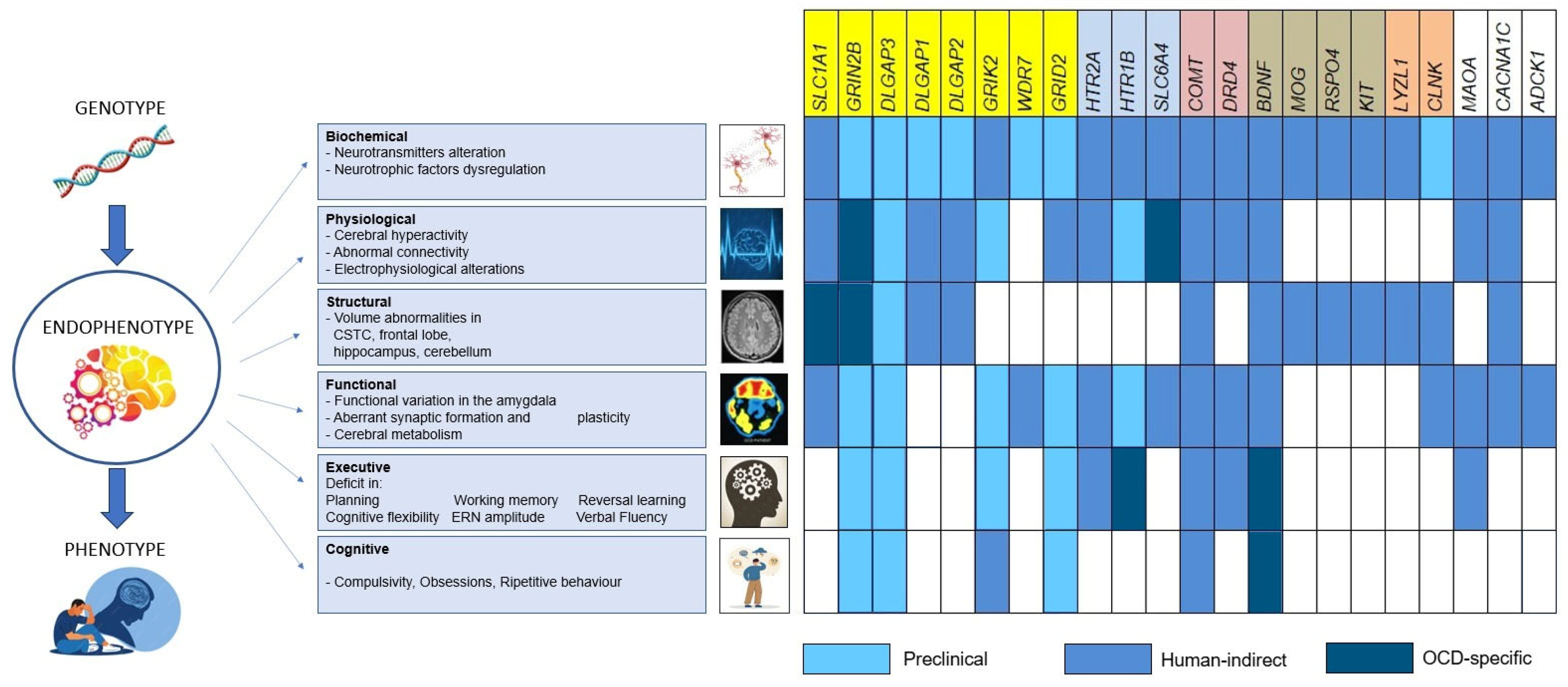

4. Endophenotypes

4.1. Glutamatergic Genes

4.2. Serotonergic Genes

4.3. Dopaminergic Genes

4.4. Neurotrophic and Neurodevelopmental Genes

4.5. Immune-Linked Genes

4.6. Other Genes

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OCD | Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder |

| GWAS | Genome Wide Association Study |

| CNV | Copy Number Variation |

| WES | Whole Exome Sequencing |

| WGS | Whole Genome Sequencing |

| MWAS | Methylome-Wide Association Studies |

| EWAS | Epigenomic-Wide Association Studies |

| CSTC | Cortico–Striato–Thalamo–Cortical |

| PFC | Prefrontal cortex |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| MRS | Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| OFC | Orbitofrontal Cortex |

| DMP | Differentially Methylated Position |

| DMR | Differentially Methylated Region |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR®), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de la Cruz, L.; Rydell, M.; Runeson, B.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Brander, G.; Rück, C.; Lichtenstein, P.; Larsson, H.; Mataix-Cols, D. Suicide in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: A Population-Based Study of 36 788 Swedish Patients. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1626–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampaloni, I.; Morris, L.; Tyagi, H.; Pessina, E.; Marriott, S.; Fischer, C.; Mohamed, H.; Govender, A.; Chandler, A.; Pallanti, S. Clarifying the Prevalence of OCD: A Response to Reader Comments. Compr. Psychiatry 2024, 135, 152492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteford, H.A.; Degenhardt, L.; Rehm, J.; Baxter, A.J.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.E.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Flaxman, A.D.; Johns, N.; et al. Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Mental and Substance Use Disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013, 382, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestadt, G.; Samuels, J.; Riddle, M.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Liang, K.-Y.; LaBuda, M.; Walkup, J.; Grados, M.; Hoehn-Saric, R. A Family Study of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.-H.; Cheng, C.-M.; Tsai, S.-J.; Bai, Y.-M.; Li, C.-T.; Lin, W.-C.; Su, T.-P.; Chen, T.-J.; Chen, M.-H. Familial Coaggregation of Major Psychiatric Disorders among First-Degree Relatives of Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Nationwide Study. Transl. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataix-Cols, D.; Boman, M.; Monzani, B.; Rück, C.; Serlachius, E.; Långström, N.; Lichtenstein, P. Population-Based, Multigenerational Family Clustering Study of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Vieira, T.; Radua, J.; Marcelino, L.; Bloch, M.; Mataix-Cols, D.; do Rosário, M.C. The Genetic Epidemiology of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.H.; Karimian, M.; Mirzaei, H.; Milajerdi, A. Epigenetic Modifications and Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: What Do We Know? Brain Struct. Funct. 2023, 228, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, A.; Mathews, C.A. Meta-analysis of the Association between the Catecholamine-O-methyl-transferase Gene and Obsessive-compulsive Disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2003, 123B, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. Molecular Genetics of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of Genetic Association Studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Hanna, G.L.; Rosenberg, D.R.; Arnold, P.D. The Role of Glutamate Signaling in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2012, 100, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerentes, M.; Pelissolo, A.; Rajagopal, K.; Tamouza, R.; Hamdani, N. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Autoimmunity and Neuroinflammation. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strom, N.I.; Gerring, Z.F.; Galimberti, M.; Yu, D.; Halvorsen, M.W.; Abdellaoui, A.; Rodriguez-Fontenla, C.; Sealock, J.M.; Bigdeli, T.; Coleman, J.R.; et al. Genome-Wide Analyses Identify 30 Loci Associated with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halvorsen, M.W.; de Schipper, E.; Bäckman, J.; Strom, N.I.; Hagen, K.; Chen, L.L.; Djurfeldt, D.R.; Höffler, K.D.; Kähler, A.K.; Lichtenstein, P.; et al. A Burden of Rare Copy Number Variants in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 1510–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S.B.; Olfson, E.; Cappi, C.; Greenspun, S.; Zai, G.; Rosário, M.C.; Willsey, A.J.; Shavitt, R.G.; Miguel, E.C.; Kennedy, J.L.; et al. Characterizing Rare DNA Copy-Number Variants in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjani, B.; Birnbaum, R.; Buxbaum Grice, A.; Cappi, C.; Jung, S.; Avila, M.N.; Reichenberg, A.; Sandin, S.; Hultman, C.M.; Buxbaum, J.D.; et al. Phenotypic Impact of Rare Potentially Damaging Copy Number Variation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Chronic Tic Disorders. Genes 2022, 13, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappi, C.; Oliphant, M.E.; Péter, Z.; Zai, G.; Conceição do Rosário, M.; Sullivan, C.A.W.; Gupta, A.R.; Hoffman, E.J.; Virdee, M.; Olfson, E.; et al. De Novo Damaging DNA Coding Mutations Are Associated with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Overlap with Tourette’s Disorder and Autism. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, M.; Samuels, J.; Wang, Y.; Greenberg, B.D.; Fyer, A.J.; McCracken, J.T.; Geller, D.A.; Knowles, J.A.; Zoghbi, A.W.; Pottinger, T.D.; et al. Exome Sequencing in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder Reveals a Burden of Rare Damaging Coding Variants. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappi, C.; Brentani, H.; Lima, L.; Sanders, S.J.; Zai, G.; Diniz, B.J.; Reis, V.N.S.; Hounie, A.G.; Conceição do Rosário, M.; Mariani, D.; et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Identifies Rare Mutations in Immunological and Neurodevelopmental Pathways. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.N.; Song, W.; Wang, W.; Wang, P.; Yu, H.; Cai, W.; Jiang, X.; Huang, W.; Qian, W.; Chen, Y.; et al. De Novo Mutations Identified by Whole-Genome Sequencing Implicate Chromatin Modifications in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabi6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullana, M.A.; Abramovitch, A.; Via, E.; López-Sola, C.; Goldberg, X.; Reina, N.; Fortea, L.; Solanes, A.; Buckley, M.J.; Ramella-Cravaro, V.; et al. Diagnostic Biomarkers for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Reasonable Quest or Ignis Fatuus? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 118, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jannatdoust, P.; Valizadeh, P.; Bagherieh, S.; Cattarinussi, G.; Sambataro, F.; Cirella, L.; Delvecchio, G. Neuroimaging Alterations in Relatives of Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Review of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 384, 180–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boedhoe, P.S.W.; Schmaal, L.; Abe, Y.; Ameis, S.H.; Arnold, P.D.; Batistuzzo, M.C.; Benedetti, F.; Beucke, J.C.; Bollettini, I.; Bose, A.; et al. Distinct Subcortical Volume Alterations in Pediatric and Adult OCD: A Worldwide Meta- and Mega-Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibar, D.P.; Cheung, J.W.; Medland, S.E.; Mufford, M.S.; Jahanshad, N.; Dalvie, S.; Ramesar, R.; Stewart, E.; van den Heuvel, O.A.; Pauls, D.L.; et al. Significant Concordance of Genetic Variation That Increases Both the Risk for Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder and the Volumes of the Nucleus Accumbens and Putamen. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honea, R.; Verchinski, B.A.; Pezawas, L.; Kolachana, B.S.; Callicott, J.H.; Mattay, V.S.; Weinberger, D.R.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Impact of Interacting Functional Variants in COMT on Regional Gray Matter Volume in Human Brain. Neuroimage 2009, 45, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.T.; Fineberg, N.A.; Pellegrini, L.; Laws, K.R. The Relationship between Cognitive Phenotypes of Compulsivity and Impulsivity and Clinical Variables in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Compr. Psychiatry 2024, 133, 152491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.; Hajcak, G.; Hayden, E.; Sheikh, H.I.; Singh, S.M.; Klein, D.N. A Genetic Variant Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Polymorphism Interacts with Hostile Parenting to Predict Error-Related Brain Activity and Thereby Risk for Internalizing Disorders in Children. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.E.; Mayerfeld, C.; Arnold, P.D.; Crane, J.R.; O’Dushlaine, C.; Fagerness, J.A.; Yu, D.; Scharf, J.M.; Chan, E.; Kassam, F.; et al. Meta-analysis of Association between Obsessive-compulsive Disorder and the 3′ Region of Neuronal Glutamate Transporter Gene SLC1A1. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2013, 162, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, L.C.; Cappi, C.; Simpson, H.B.; Stein, D.J.; Viswanath, B.; van den Heuvel, O.A.; Reddy, Y.J.; Miguel, E.C.; Shavitt, R.G. Cutting-Edge Genetics in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Fac. Rev. 2020, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjani, B.; Bey, K.; Boberg, J.; Burton, C. Genetics of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 2247–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Braber, A.; Zilhão, N.R.; Fedko, I.O.; Hottenga, J.-J.; Pool, R.; Smit, D.J.A.; Cath, D.C.; Boomsma, D.I. Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms in a Large Population-Based Twin-Family Sample Are Predicted by Clinically Based Polygenic Scores and by Genome-Wide SNPs. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, C.L.; Lemire, M.; Xiao, B.; Corfield, E.C.; Erdman, L.; Bralten, J.; Poelmans, G.; Yu, D.; Shaheen, S.-M.; Goodale, T.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Traits: Shared Genetic Risk between Traits and Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, L.M.; Yu, D.; Marshall, C.; Davis, L.K.; Thiruvahindrapuram, B.; Li, B.; Cappi, C.; Gerber, G.; Wolf, A.; Schroeder, F.A.; et al. Copy Number Variation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Tourette Syndrome: A Cross-Disorder Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 53, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrei, M.; Burton, C.L.; Engchuan, W.; Young, E.J.; Higginbotham, E.J.; MacDonald, J.R.; Trost, B.; Chan, A.J.S.; Walker, S.; Lamoureux, S.; et al. A Large Data Resource of Genomic Copy Number Variation across Neurodevelopmental Disorders. NPJ Genom. Med. 2019, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmelkov, S.V.; Hormigo, A.; Jing, D.; Proenca, C.C.; Bath, K.G.; Milde, T.; Shmelkov, E.; Kushner, J.S.; Baljevic, M.; Dincheva, I.; et al. Slitrk5 Deficiency Impairs Corticostriatal Circuitry and Leads to Obsessive-Compulsive-Like Behaviors in Mice. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Mathews, C.A.; Stewart, S.E.; Shmelkov, S.V.; Mezey, J.G.; Rodriguez-Flores, J.L.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Britton, J.C.; Oh, Y.-S.; Walkup, J.T.; et al. Rare Synaptogenesis-Impairing Mutations in SLITRK5 Are Associated with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Cheng, W.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Lu, T.; Zhang, D.; Tang, M.; Huang, Y. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Patients. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappi, C.; Diniz, J.B.; Requena, G.L.; Lourenço, T.; Lisboa, B.C.G.; Batistuzzo, M.C.; Marques, A.H.; Hoexter, M.Q.; Pereira, C.A.; Miguel, E.C.; et al. Epigenetic Evidence for Involvement of the Oxytocin Receptor Gene in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. BMC Neurosci. 2016, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellia, F.; Vismara, M.; Annunzi, E.; Cifani, C.; Benatti, B.; Dell’Osso, B.; D’Addario, C. Genetic and Epigenetic Architecture of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: In Search of Possible Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 137, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiele, M.A.; Lipovsek, J.; Schlosser, P.; Soutschek, M.; Schratt, G.; Zaudig, M.; Berberich, G.; Köttgen, A.; Domschke, K. Epigenome-Wide DNA Methylation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Martin, R.; Bey, K.; Elsner, B.; Reuter, B.; Klawohn, J.; Philipsen, A.; Kathmann, N.; Wagner, M.; Ramirez, A. Epigenome-Wide Analysis Identifies Methylome Profiles Linked to Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Disease Severity, and Treatment Response. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 4321–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höffler, K.D.; Stavrum, A.-K.; Halvorsen, M.W.; Eide, T.O.; Hagen, K.; Høberg, A.; Kvale, G.; Crowley, J.J.; Haavik, J.; Ressler, K.J.; et al. Methylome-Wide Association Study of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remenyi, J.; Hunter, C.J.; Cole, C.; Ando, H.; Impey, S.; Monk, C.E.; Martin, K.J.; Barton, G.J.; Hutvagner, G.; Arthur, J.S.C. Regulation of the MiR-212/132 Locus by MSK1 and CREB in Response to Neurotrophins. Biochem. J. 2010, 428, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Hou, X.; Chen, X.; Cheng, M.; Wen, S. Dysregulated Plasma Levels of MiRNA-132 and MiRNA-134 in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirdogan Aydin, E.; Alsaadoni, H.; Gokovali Begenen, A.; Ozer, O.A.; Karamustafalioglu, K.O.; Pence, S. Can MiRNA Expression Levels Predict Treatment Resistance to Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 32, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, N.D.; Elibol, B.; Durmus, Z.; Ozdemir, A.; Akbas, F.; Guloksuz, S.; Sahbaz, C.D. Evaluation of Potential Biomarker MiRNAs and the Levels of Serotonin and Dopamine in Female Patients with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Neuroscience 2025, 581, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunoz, S.; Dolapoglu, N.; Baykan, O.; Bolat, H.; Avcikurt, A.S.; Karlidere, T. Could Transforming Growth Factor Beta and Target MicroRNA Dysregulation Serve as Biomarkers of Symptom Severity in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2025, 85, e70070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirdoğan Aydın, E.; Demirci, H.; Gokovali Begenen, A.; Alsaadoni, H.; Özer, Ö.A. The Relationship between MiRNAs and Executive Functions in Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: An Exploratory Analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2025, 28, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Teng, C.; Xu, Y.; Tian, L.; Cao, P.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Guan, C.; Hu, X. Genetic and Molecular Correlates of Cortical Thickness Alterations in Adults with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: A Transcription–Neuroimaging Association Analysis. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 3469–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milad, M.R.; Rauch, S.L. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Beyond Segregated Cortico-Striatal Pathways. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012, 16, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beucke, J.C.; Sepulcre, J.; Talukdar, T.; Linnman, C.; Zschenderlein, K.; Endrass, T.; Kaufmann, C.; Kathmann, N. Abnormally High Degree Connectivity of the Orbitofrontal Cortex in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apergis-Schoute, A.M.; Bijleveld, B.; Gillan, C.M.; Fineberg, N.A.; Sahakian, B.J.; Robbins, T.W. Hyperconnectivity of the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Brain Neurosci. Adv. 2018, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, P.D.; Sicard, T.; Burroughs, E.; Richter, M.A.; Kennedy, J.L. Glutamate Transporter Gene SLC1A1 Associated with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porton, B.; Greenberg, B.D.; Askland, K.; Serra, L.M.; Gesmonde, J.; Rudnick, G.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Kao, H.-T. Isoforms of the Neuronal Glutamate Transporter Gene, SLC1A1/EAAC1, Negatively Modulate Glutamate Uptake: Relevance to Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3, e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zike, I.D.; Chohan, M.O.; Kopelman, J.M.; Krasnow, E.N.; Flicker, D.; Nautiyal, K.M.; Bubser, M.; Kellendonk, C.; Jones, C.K.; Stanwood, G.; et al. OCD Candidate Gene SLC1A1/EAAT3 Impacts Basal Ganglia-Mediated Activity and Stereotypic Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 5719–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, P.D.; MacMaster, F.P.; Hanna, G.L.; Richter, M.A.; Sicard, T.; Burroughs, E.; Mirza, Y.; Easter, P.C.; Rose, M.; Kennedy, J.L.; et al. Glutamate System Genes Associated with Ventral Prefrontal and Thalamic Volume in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Brain Imaging Behav. 2009, 3, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arnold, P.D.; MacMaster, F.P.; Richter, M.A.; Hanna, G.L.; Sicard, T.; Burroughs, E.; Mirza, Y.; Easter, P.C.; Rose, M.; Kennedy, J.L.; et al. Glutamate Receptor Gene (GRIN2B) Associated with Reduced Anterior Cingulate Glutamatergic Concentration in Pediatric Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2009, 172, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jung, W.B.; Moon, H.; Im, G.H.; Noh, Y.W.; Shin, W.; Kim, Y.G.; Yi, J.H.; Hong, S.J.; Jung, Y.; et al. Anterior Cingulate Cortex-Related Functional Hyperconnectivity Underlies Sensory Hypersensitivity in Grin2b-Mutant Mice. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 3195–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigman, J.L.; Daut, R.A.; Wright, T.; Gunduz-Cinar, O.; Graybeal, C.; Davis, M.I.; Jiang, Z.; Saksida, L.M.; Jinde, S.; Pease, M.; et al. GluN2B in Corticostriatal Circuits Governs Choice Learning and Choice Shifting. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, J.M.; Lu, J.; Rodriguiz, R.M.; Trotta, N.C.; Peca, J.; Ding, J.-D.; Feliciano, C.; Chen, M.; Adams, J.P.; Luo, J.; et al. Cortico-Striatal Synaptic Defects and OCD-like Behaviours in Sapap3-Mutant Mice. Nature 2007, 448, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Lai, J.; Sun, X.; Xu, Q.; Feng, G. Lateral Orbitofrontal Dysfunction in the Sapap3 Knockout Mouse Model of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019, 44, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamothe, H.; Schreiweis, C.; Mondragón-González, L.S.; Rebbah, S.; Lavielle, O.; Mallet, L.; Burguière, E. The Sapap3−/− Mouse Reconsidered as a Comorbid Model Expressing a Spectrum of Pathological Repetitive Behaviours. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Ade, K.K.; Caffall, Z.; Ilcim Ozlu, M.; Eroglu, C.; Feng, G.; Calakos, N. Circuit-Selective Striatal Synaptic Dysfunction in the Sapap3 Knockout Mouse Model of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Züchner, S.; Wendland, J.R.; Ashley-Koch, A.E.; Collins, A.L.; Tran-Viet, K.N.; Quinn, K.; Timpano, K.C.; Cuccaro, M.L.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Steffens, D.C.; et al. Multiple Rare SAPAP3 Missense Variants in Trichotillomania and OCD. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bienvenu, O.J.; Wang, Y.; Shugart, Y.Y.; Welch, J.M.; Grados, M.A.; Fyer, A.J.; Rauch, S.L.; McCracken, J.T.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Murphy, D.L.; et al. Sapap3 and Pathological Grooming in Humans: Results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2009, 150B, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.E.; Yu, D.; Scharf, J.M.; Neale, B.M.; Fagerness, J.A.; Mathews, C.A.; Arnold, P.D.; Evans, P.D.; Gamazon, E.R.; Osiecki, L.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünblatt, E.; Hauser, T.U.; Walitza, S. Imaging Genetics in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Linking Genetic Variations to Alterations in Neuroimaging. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 121, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrete-Díaz, J.V.; Falcón-Moya, R.; Rodríguez-Moreno, A. Kainate Receptors: From Synaptic Activity to Disease. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 5074–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryazantseva, M.; Englund, J.; Shintyapina, A.; Huupponen, J.; Shteinikov, V.; Pitkänen, A.; Partanen, J.M.; Lauri, S.E. Kainate Receptors Regulate Development of Glutamatergic Synaptic Circuitry in the Rodent Amygdala. eLife 2020, 9, e52798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheau, J.; Vimeney, A.; Normand, E.; Mulle, C.; Riedel, G. Impaired Hippocampus-dependent Spatial Flexibility and Sociability Represent Autism-like Phenotypes in GluK2 Mice. Hippocampus 2014, 24, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, N.; Awasthi, R.; Ozdogan, T.; Johenning, F.W.; Imbrosci, B.; Morris, G.; Schmitz, D.; Barkai, E. A Cellular Mechanism Underlying Enhanced Capability for Complex Olfactory Discrimination Learning. eNeuro 2019, 6, ENEURO.0198-18.2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhang, W.; Yi, Z.; Lu, W.; Wu, Z.; Chen, J.; Yu, S.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, C. Influence of Polymorphisms in Genes SLC1A1, GRIN2B, and GRIK2 on Clozapine-Induced Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms. Psychopharmacology 2013, 230, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, F.; Kawabe, H.; Nakanishi, H.; Shinohara, M.; Deguchi-Tawarada, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Sasaki, T.; Takai, Y. Rabconnectin-3, a Novel Protein That Binds Both GDP/GTP Exchange Protein and GTPase-Activating Protein for Rab3 Small G Protein Family. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 9629–9632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einhorn, Z.; Trapani, J.G.; Liu, Q.; Nicolson, T. Rabconnectin3α Promotes Stable Activity of the H+ Pump on Synaptic Vesicles in Hair Cells. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 11144–11156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crummy, E.; Mani, M.; Thellman, J.C.; Martin, T.F.J. The Priming Factor CAPS1 Regulates Dense-Core Vesicle Acidification by Interacting with Rabconnectin3β/WDR7 in Neuroendocrine Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 9402–9415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskolka, M.C.; Winkley, S.R.; Kane, P.M. RAVE and Rabconnectin-3 Complexes as Signal Dependent Regulators of Organelle Acidification. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 698190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, T.; Lee, S.-J.; Yasumura, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Yoshida, T.; Ra, M.; Taguchi, R.; Sakimura, K.; Mishina, M. Trans-Synaptic Interaction of GluRδ2 and Neurexin through Cbln1 Mediates Synapse Formation in the Cerebellum. Cell 2010, 141, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwabuchi, N.; Ikeda, K.; Araki, K.; Hirano, T.; Shibuki, K.; Takayama, C.; Inoue, Y.; Kutsuwada, T.; Yagi, T.; Kang, Y.; et al. Impairment of Motor Coordination, Purkinje Cell Synapse Formation, and Cerebellar Long-Term Depression in GluRδ2 Mutant Mice. Cell 1995, 81, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Z.; Edmiston, E.K.; Versace, A.; Fournier, J.C.; Graur, S.; Greenberg, T.; Lima Santos, J.P.; Chase, H.W.; Stiffler, R.S.; Bonar, L.; et al. Functional Disruption of Cerebello-Thalamo-Cortical Networks in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2020, 5, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzaki, M. Cerebellar LTD vs. Motor Learning—Lessons Learned from Studying GluD2. Neural Netw. 2013, 47, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, D.J.A.; Cath, D.; Zilhão, N.R.; Ip, H.F.; Denys, D.; den Braber, A.; de Geus, E.J.C.; Verweij, K.J.H.; Hottenga, J.; Boomsma, D.I. Genetic Meta-analysis of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder and Self-report Compulsive Symptoms. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2020, 183, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aznar, S.; Hervig, M.E.-S. The 5-HT2A Serotonin Receptor in Executive Function: Implications for Neuropsychiatric and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 64, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, R. Serotonergic Regulation of Neuronal Excitability in the Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropharmacology 2011, 61, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Maeso, J.; Weisstaub, N.V.; Zhou, M.; Chan, P.; Ivic, L.; Ang, R.; Lira, A.; Bradley-Moore, M.; Ge, Y.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Hallucinogens Recruit Specific Cortical 5-HT2A Receptor-Mediated Signaling Pathways to Affect Behavior. Neuron 2007, 53, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, S.; Pagerols, M.; Gassó, P.; Ortiz, A.; Rodriguez, N.; Morer, A.; Plana, M.T.; Lafuente, A.; Lazaro, L. Role of GAD2 and HTR1B Genes in Early-onset Obsessive-compulsive Disorder: Results from Transmission Disequilibrium Study. Genes Brain Behav. 2014, 13, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, R.; Roberts, A.C.; Robbins, T.W. Serotoninergic Regulation of Emotional and Behavioural Control Processes. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenberg, S.F.; Christ, C.C.; Highland, K.B. Serotonin System Gene Polymorphisms Are Associated with Impulsivity in a Context Dependent Manner. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 39, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, N.A.; Velez, L.P.; Masten, V.L.; Dulawa, S.C. Essential Role for Orbitofrontal Serotonin 1B Receptors in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder-Like Behavior and Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Response in Mice. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 70, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-Z.; Lipsky, R.H.; Zhu, G.; Akhtar, L.A.; Taubman, J.; Greenberg, B.D.; Xu, K.; Arnold, P.D.; Richter, M.A.; Kennedy, J.L.; et al. Serotonin Transporter Promoter Gain-of-Function Genotypes Are Linked to Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 78, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimold, M.; Smolka, M.N.; Zimmer, A.; Batra, A.; Knobel, A.; Solbach, C.; Mundt, A.; Smoltczyk, H.U.; Goldman, D.; Mann, K.; et al. Reduced Availability of Serotonin Transporters in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Correlates with Symptom Severity–a [11C]DASB PET Study. J. Neural Transm. 2007, 114, 1603–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, S.; Stengler, K.; Regenthal, R.; Patt, M.; Becker, G.-A.; Franke, A.; Knüpfer, H.; Meyer, P.M.; Luthardt, J.; Jahn, I.; et al. The Serotonin Transporter Availability in Untreated Early-Onset and Late-Onset Patients with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 14, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remijnse, P.L.; Nielen, M.M.A.; van Balkom, A.J.L.M.; Cath, D.C.; van Oppen, P.; Uylings, H.B.M.; Veltman, D.J. Reduced Orbitofrontal-Striatal Activity on a Reversal Learning Task in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltby, N.; Tolin, D.F.; Worhunsky, P.; O’Keefe, T.M.; Kiehl, K.A. Dysfunctional Action Monitoring Hyperactivates Frontal–Striatal Circuits in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: An Event-Related FMRI Study. Neuroimage 2005, 24, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Heuvel, O.A.; Veltman, D.J.; Groenewegen, H.J.; Cath, D.C.; van Balkom, A.J.L.M.; van Hartskamp, J.; Barkhof, F.; van Dyck, R. Frontal-Striatal Dysfunction During Planning in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, L.J.; Taylor, S.F.; Liu, Y.; Radua, J.; Chye, Y.; De Wit, S.J.; Huyser, C.; Karahanoglu, F.I.; Luks, T.; Manoach, D.; et al. Error Processing and Inhibitory Control in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis Using Statistical Parametric Maps. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 85, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckert, M.; Kudielka, B.M.; Reuter, M.; Fiebach, C.J. The COMT Val158Met Polymorphism Modulates Working Memory Performance under Acute Stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 1810–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.M.; Makeig, S.; Stemmler, G.; Hennig, J.; Wacker, J. Dopamine Effects on Human Error Processing Depend on Catechol-O-Methyltransferase VAL158MET Genotype. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 15818–15825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.M.; Burgdorf, C.; Chavanon, M.; Schweiger, D.; Hennig, J.; Wacker, J.; Stemmler, G. The COMT Val158Met Polymorphism Regulates the Effect of a Dopamine Antagonist on the Feedback-related Negativity. Psychophysiology 2014, 51, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Amelsvoort, T.; Zinkstok, J.; Figee, M.; Daly, E.; Morris, R.; Owen, M.J.; Murphy, K.C.; De Haan, L.; Linszen, D.H.; Glaser, B.; et al. Effects of a Functional COMT Polymorphism on Brain Anatomy and Cognitive Function in Adults with Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Qin, W.; Li, Q.; Li, W.; Liu, F.; Liu, B.; Jiang, T.; Yu, C. Prefrontal Volume Mediates Effect of COMT Polymorphism on Interference Resolution Capacity in Healthy Male Adults. Cereb. Cortex 2016, 27, 5211–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Qin, W.; Liu, B.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Jiang, T.; Yu, C. Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Val158Met Polymorphism Modulates Gray Matter Volume and Functional Connectivity of the Default Mode Network. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, S.; Belcher, A.M.; Bonaventura, J.; Quiroz, C.; Sánchez-Soto, M.; Casadó-Anguera, V.; Cai, N.-S.; Moreno, E.; Boateng, C.A.; Keck, T.M.; et al. Functional and Pharmacological Role of the Dopamine D4 Receptor and Its Polymorphic Variants. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1014678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptacek, R.; Kuzelova, H.; Stefano, G.B. Dopamine D4 Receptor Gene DRD4 and Its Association with Psychiatric Disorders. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011, 17, RA215–RA220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, M.F.; Kojima, M.; Callicott, J.H.; Goldberg, T.E.; Kolachana, B.S.; Bertolino, A.; Zaitsev, E.; Gold, B.; Goldman, D.; Dean, M.; et al. The BDNF Val66met Polymorphism Affects Activity-Dependent Secretion of BDNF and Human Memory and Hippocampal Function. Cell 2003, 112, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tükel, R.; Gürvit, H.; Özata, B.; Öztürk, N.; Ertekin, B.A.; Ertekin, E.; Baran, B.; Kalem, Ş.A.; Büyükgök, D.; Direskeneli, G.S. Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor Gene Val66Met Polymorphism and Cognitive Function in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2012, 159B, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zai, G.; Bezchlibnyk, Y.B.; Richter, M.A.; Arnold, P.; Burroughs, E.; Barr, C.L.; Kennedy, J.L. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG) Gene Is Associated with Obsessive-compulsive Disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2004, 129B, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaydon, D.C.; Ishii, Y.; O’Toole, E.A.; Unsworth, H.C.; Teh, M.-T.; Rüschendorf, F.; Sinclair, C.; Hopsu-Havu, V.K.; Tidman, N.; Moss, C.; et al. The Gene Encoding R-Spondin 4 (RSPO4), a Secreted Protein Implicated in Wnt Signaling, Is Mutated in Inherited Anonychia. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 1245–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasif, N.; Ahmad, W. A Novel Nonsense Mutation in RSPO4 Gene Underlies Autosomal Recessive Congenital Anonychia in a Pakistani Family. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2013, 30, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.Y.; Davidson, D.; Yu, J.; Latour, S.; Veillette, A. Clnk, a Novel Slp-76–Related Adaptor Molecule Expressed in Cytokine-Stimulated Hemopoietic Cells. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 190, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolla, N.J.; Bortolato, M. The Role of Monoamine Oxidase A in the Neurobiology of Aggressive, Antisocial, and Violent Behavior: A Tale of Mice and Men. Prog. Neurobiol. 2020, 194, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolato, M.; Chen, K.; Shih, J.C. Monoamine Oxidase Inactivation: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ming, Q.; Zhong, X.; Dong, D.; Li, C.; Xiong, G.; Cheng, C.; Cao, W.; He, J.; Wang, X.; et al. The MAOA Gene Influences the Neural Response to Psychosocial Stress in the Human Brain. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckholtz, J.W.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. MAOA and the Neurogenetic Architecture of Human Aggression. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Buckholtz, J.W.; Kolachana, B.; Hariri, A.R.; Pezawas, L.; Blasi, G.; Wabnitz, A.; Honea, R.; Verchinski, B.; Callicott, J.H.; et al. Neural Mechanisms of Genetic Risk for Impulsivity and Violence in Humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 6269–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, A.; McClay, J.; Moffitt, T.E.; Mill, J.; Martin, J.; Craig, I.W.; Taylor, A.; Poulton, R. Role of Genotype in the Cycle of Violence in Maltreated Children. Science (1979) 2002, 297, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussos, P.; Giakoumaki, S.G.; Georgakopoulos, A.; Robakis, N.K.; Bitsios, P. The CACNA1C and ANK3 Risk Alleles Impact on Affective Personality Traits and Startle Reactivity but Not on Cognition or Gating in Healthy Males. Bipolar Disord. 2011, 13, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, J.M.; Navas, P. Regulation of Coenzyme Q Biosynthesis Pathway in Eukaryotes. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 165, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, N.; Zhao, Y. The ADCK Kinase Family: Key Regulators of Bioenergetics and Mitochondrial Function and Their Implications in Human Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotzinger, A.D.; Werme, J.; Peyrot, W.J.; Frei, O.; de Leeuw, C.; Bicks, L.K.; Guo, Q.; Margolis, M.P.; Coombes, B.J.; Batzler, A.; et al. Mapping the genetic landscape across 14 psychiatric disorders. Nature 2025, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Meur, N.; Holder-Espinasse, M.; Jaillard, S.; Goldenberg, A.; Joriot, S.; Amati-Bonneau, P.; Guichet, A.; Barth, M.; Charollais, A.; Journel, H.; et al. MEF2C Haploinsufficiency Caused by Either Microdeletion of the 5q14.3 Region or Mutation Is Responsible for Severe Mental Retardation with Stereotypic Movements, Epilepsy and/or Cerebral Malformations. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 47, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.C.; Skinner, S.A. MEF2C-Related Disorder. In GeneReviews; Adam, M.P., Bick, S., Mirzaa, G.M., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, H.; Tang, Q.; Guo, R.; Cao, G.; Feng, Y.; Sun, X.; Lu, H. Genetic Analysis of a Child with Complex Cortical Dysplasia with Other Brain Malformations Type 6 Due to a p.M73V Variant of the TUBB Gene. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi 2023, 40, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahi-Buisson, N.; Maillard, C. Tubulinopathies Overview. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Bick, S., Mirzaa, G.M., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guler, S.; Aslanger, A.D.; Uygur Sahin, T.; Alkan, A.; Yalcinkaya, C.; Saltik, S.; Yesil, G. Long-Term Disease Course of Pontocerebellar Hypoplasia Type 10. Pediatr. Neurol. 2024, 158, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaghan, C.E.; Adamson, S.I.; Kapur, M.; Chuang, J.H.; Ackerman, S.L. The Clp1 R140H Mutation Alters TRNA Metabolism and MRNA 3′ Processing in Mouse Models of Pontocerebellar Hypoplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2110730118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, J.H.; Go, G.; Cunningham, J.; Patton, B.L.; Jarad, G. Transgenic Isolation of Skeletal Muscle and Kidney Defects in Lamininβ2 Mutant Mice: Implications for Pierson Syndrome. Development 2006, 133, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matejas, V.; Hinkes, B.; Alkandari, F.; Al-Gazali, L.; Annexstad, E.; Aytac, M.B.; Barrow, M.; Bláhová, K.; Bockenhauer, D.; Cheong, H.I.; et al. Mutations in the Human Laminin Β2 (LAMB2) Gene and the Associated Phenotypic Spectruma. Hum. Mutat. 2010, 31, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikkawa, Y.; Hashimoto, T.; Takizawa, K.; Urae, S.; Masuda, H.; Matsunuma, M.; Yamada, Y.; Hamada, K.; Nomizu, M.; Liapis, H.; et al. Laminin Β2 Variants Associated with Isolated Nephropathy That Impact Matrix Regulation. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e145908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, A.; Karasawa, T.; Tago, K.; Kimura, H.; Kamata, R.; Usui-Kawanishi, F.; Watanabe, S.; Ohta, S.; Funakoshi-Tago, M.; Yanagisawa, K.; et al. ARIH2 Ubiquitinates NLRP3 and Negatively Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 3614–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, M.; Treccarichi, S.; Galati Rando, R.; Musumeci, A.; Todaro, V.; Federico, C.; Saccone, S.; Elia, M.; Calì, F. A de Novo ARIH2 Gene Mutation Was Detected in a Patient with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Intellectual Disability. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattheisen, M.; Samuels, J.F.; Wang, Y.; Greenberg, B.D.; Fyer, A.J.; McCracken, J.T.; Geller, D.A.; Murphy, D.L.; Knowles, J.A.; Grados, M.A.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Results from the OCGAS. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzellone, M.J.; Zarrei, M.; Burton, C.L.; Walker, S.; Uddin, M.; Shaheen, S.M.; Coste, J.; Rajendram, R.; Schachter, R.J.; Colasanto, M.; et al. Uncovering Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Risk Genes in a Pediatric Cohort by High-Resolution Analysis of Copy Number Variation. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2016, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation Genetics Collaborative (IOCDF-GC); OCD Collaborative Genetics Association Studies (OCGAS). Revealing the Complex Genetic Architecture of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder Using Meta-Analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1181–1188. [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.-F.; Yan, Y.-T.; Wu, S.-Y.; Djoko, B.; Tsai, M.-T.; Cheng, C.-J.; Yang, R.-B. Domain and Functional Analysis of a Novel Platelet-Endothelial Cell Surface Protein, SCUBE1. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 12478–12488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, G.M.; Sharpe, P.T.; Cobourne, M.T. Scube1 Is Expressed during Facial Development in the Mouse. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2009, 312B, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Name | Function | Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLC25A17 | Solute carrier family 25 member 17 | Peroxisomal transporter of CoA and related cofactors involved in lipid and oxidative metabolism. | Peroxisomal/mitochondrial metabolism |

| ATP5MC1 | ATP synthase membrane subunit c locus 1 | Subunit of mitochondrial ATP synthase proton channel required for oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production. | Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation |

| ZDHHC5 | zDHHC palmitoyltransferase 5 | Palmitoyltransferase that controls membrane localization and trafficking of synaptic and signalling proteins. | Palmitoylation/synaptic trafficking |

| IER3 | Immediate early response 3 | Stress-inducible regulator of cell survival and apoptosis in immune and inflammatory signalling. | Stress response/immune–apoptotic signalling |

| CCDC71 | Coiled-coil domain containing 71 | Coiled-coil scaffold protein implicated in cytoskeletal organisation and intracellular signalling complexes. | Cytoskeleton/scaffold |

| XPNPEP3 | X-prolyl aminopeptidase 3 | Mitochondrial metallopeptidase involved in peptide processing and ciliary/renal function. | Mitochondrial/ciliary function |

| ACSF2 | Acyl-CoA synthetase family member 2 | Acyl-CoA synthetase contributing to mitochondrial fatty-acid activation and lipid metabolism. | Lipid metabolism/mitochondria |

| CTNND1 | Catenin delta 1 | Catenin family adaptor linking cadherin-mediated cell adhesion to intracellular signalling and cytoskeletal dynamics. | Cell adhesion/junctional signalling |

| MEF2C | Myocyte enhancer factor 2C | Transcription factor regulating neuronal differentiation, synaptic plasticity, and broader neurodevelopmental programmes. | Transcriptional regulation/neurodevelopment |

| KLHDC8B | Kelch domain containing 8B | Kelch-repeat β-propeller protein organising protein complexes during mitosis and cell-cycle progression. | Cytoskeletal/cell-cycle regulation |

| YWHAB | Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein beta | Phosphoserine-binding 14-3-3 adaptor that integrates kinase signalling and cell-cycle control. | Intracellular/synaptic signalling |

| UBE2Z | Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 Z | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) that tags substrates for proteasomal degradation and signalling regulation. | Ubiquitin–proteasome/signalling |

| TRIM27 | Tripartite motif containing 27 | RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in transcriptional repression and developmental signalling pathways. | Transcriptional repression/ubiquitin signalling |

| ARIH2 | Ariadne RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 | RBR E3 ubiquitin ligase implicated in Hedgehog signalling, immune regulation and protein quality control. | Ubiquitin ligase/immune–developmental |

| DALRD3 | DALR anticodon binding domain containing 3 | tRNA-binding protein thought to modulate translation and RNA metabolism. | RNA metabolism/translation |

| PABPC1L | Poly(A) binding protein cytoplasmic 1 like | Cytoplasmic poly(A)-binding protein controlling mRNA stability and translation during early development. | mRNA stability/translation |

| CLP1 | Cleavage factor polyribonucleotide kinase subunit 1 | RNA kinase in tRNA splicing and pre-mRNA 3′-end processing; essential for normal neurodevelopment. | RNA processing/neurodevelopment |

| TUBB | Tubulin beta class I | β-tubulin isoform forming microtubules critical for neuronal morphology and axonal transport. | Cytoskeleton/microtubules |

| LAMB2 | Laminin subunit beta 2 | Laminin β2 subunit in basement membranes, mediating cell adhesion, neurite outgrowth, and synapse stabilisation. | Extracellular matrix/synaptic connectivity |

| WDR6 | WD repeat domain 6 | WD-repeat scaffold protein interacting with LKB1 and implicated in growth and metabolic signalling. | Signalling scaffold/growth regulation |

| AURKB | Aurora kinase B | Serine/threonine kinase controlling chromosome segregation and mitotic spindle dynamics. | Cell-cycle/mitosis |

| TMX2 | Thioredoxin related transmembrane protein 2 | ER-resident thioredoxin-like protein involved in redox-dependent protein folding at mitochondria-associated membranes. | ER stress/redox homeostasis |

| FLOT1 | Flotillin 1 | Membrane-raft protein participating in endocytosis, vesicle trafficking, and organisation of signalling microdomains. | Membrane microdomains/vesicle trafficking |

| P4HTM | Prolyl 4-hydroxylase, transmembrane | ER prolyl-4-hydroxylase regulating HIFα stability and cellular responses to oxygen tension. | Hypoxia/HIF signalling |

| MAIP1 | Matrix AAA peptidase interacting protein 1 | Mitochondrial matrix protein supporting ribosome binding and calcium-dependent mitochondrial homeostasis. | Mitochondrial function/Ca2+ homeostasis |

| Gene | Full Name | Function (Short) | Pathway | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDE1 | Nuclear distribution element 1 | Centrosomal/microtubule-associated protein required for neuronal proliferation, migration and cortical development. | Neurodevelopment/microtubule–centrosome | Mahjani et al., 2022 [17] |

| MIR484 | MicroRNA 484 | Brain-expressed miRNA at 16p13.11 that modulates neurogenesis and protocadherin-19 signalling in experimental models. | miRNA regulation/neurodevelopment | Mahjani et al., 2022 [17] |

| SMAD2 | SMAD family member 2 | Intracellular effector of TGF-β signalling controlling cell proliferation, differentiation, and early neurodevelopment. | TGF-β/neurodevelopment | Abdallah et al., 2025 [16] |

| MDM2 | MDM2 proto-oncogene, E3 ubiquitin ligase | Negative regulator of p53 that controls cell-cycle progression and apoptosis, influencing cortical proliferation/survival. | Cell-cycle/p53–apoptosis | Abdallah et al., 2025 [16] |

| ANAPC1 | Anaphase-promoting complex subunit 1 | Core component of the APC/C E3 ubiquitin ligase complex required for mitotic progression and neurodevelopmental timing. | Cell-cycle/ubiquitin ligase | Abdallah et al., 2025 [16] |

| Gene | Full Name | Function (Short) | Pathway | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD8 | Chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 8 | Chromatin-remodelling factor that regulates large neurodevelopmental gene networks; high-confidence ASD/neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) risk gene. | Chromatin remodelling/neurodevelopment | Cappi et al., 2020 [18] |

| SCUBE1 | Signal peptide, CUB domain and EGF-like domain-containing protein 1 | Secreted EGF-related glycoprotein involved in early CNS and vascular development and growth-factor signalling. | Growth-factor signalling/neurovascular | Cappi et al., 2020 [18] |

| SLITRK5 | SLIT and NTRK-like family member 5 | Postsynaptic adhesion molecule regulating excitatory/inhibitory synapse formation within cortico-striatal circuits. | Synaptic adhesion/CSTC signalling | Halvorsen et al., 2021 [19] |

| SETD5 | SET domain-containing protein 5 | Histone lysine methyltransferase that regulates broad neurodevelopmental transcriptional programmes; LoF causes NDD with ID/ASD. | Chromatin modification/neurodevelopment | Lin et al., 2022 [21] |

| KDM3B | Lysine demethylase 3B | H3K9 histone demethylase essential for epigenetic control of transcription; pathogenic variants cause Diets–Jongmans syndrome. | Epigenetic regulation/transcription | Lin et al., 2022 [21] |

| ASXL3 | Additional sex combs-like protein 3 | Scaffold for chromatin-remodelling complexes; truncating variants cause Bainbridge–Ropers syndrome with severe NDD. | Chromatin remodelilng/epigenetic control | Lin et al., 2022 [21] |

| FBL | Fibrillarin | Core nucleolar 2′-O-methyltransferase of box C/D snoRNPs linking rRNA modification, ribosome biogenesis and transcriptional control. | Ribosome biogenesis/RNA–chromatin interface | Lin et al., 2022 [21] |

| Epigenetic/chromatin/transcriptional regulation DNMT3A, DAXX, GADD45A, CBFA2T3, FAM120B, HIVEP3, HEMK1, RBM47, LINC00511, LINC01271, LINC01996, RN7SL363P, RPL17P34, ZNF833P, MIR29A, MIR21, MIR4489, HNRNPA1P10, EEF1A1P49 |

| Neurotransmission and CSTC synaptic signalling GABBR1, GABRB3, GPRIN3, RIN1, ADGRB1 (BAI1), ARHGEF17, ARHGEF10, ZNRF1, SLC12A7 (KCC4), KIFC3 |

| Neurodevelopment, cell polarity and structural plasticity DCHS1, TUBGCP3, ABLIM1, PGBD5, PIWIL1, TEX26, TEX26-AS1, DYNLT4, BTBD19, DLL1, DSE |

| Immune/inflammatory and barrier-related pathways CSF1, TRIM14, LY6E, SBNO2, ABCA7, B3GALT4, CCR1, PTPRJ, MUC2, VMP1, MCRIP1, ADAMTS2, RUNX3 |

| Mitochondrial, lysosomal and metabolic pathways NDUFS7, SNN, PLA2G15, APOB, NAA16, MOB3A |

| Endophenotype | What It Captures | Technique Families |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemical | Neurotransmission and molecular signalling | Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) Molecular imaging (PET/SPECT) Biofluid biomarker assays Cell-based/iPSC-derived neuronal assays |

| Physiological | Circuit excitability and timing | Electroencephalogram/Magnetoencephalography (EEG/MEG) Electromyography Functional Positron Emission Tomography (fPET) Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) |

| Structural | Morphometry and microstructure | Structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (qMRI) |

| Functional | Systems-level activation and connectivity | Task-based functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (Task-fMRI) Resting-state functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (Resting-state fMRI) Perfusion Arterial Spin Labelling Magnetic Resonance Imaging (ASL MRI) Positron Emission Tomography with Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG PET) |

| Executive | Inhibitory control and flexibility | Neuropsychological tasks Computational assays |

| Cognitive | Learning and memory profiles | Memory/learning batteries Associative/extinction tasks Habit/procedural tasks |

| Ref. | Study | Design | Sample Size | Population/Ancestry | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | Strom et al., 2025 | GWAS meta-analysis | 53,660 cases; 2,044,417 controls | European ancestry | Identified 30 loci; used imputed GWAS datasets. |

| [15] | Halvorsen et al., 2025 | CNV burden analysis (microarray) | 2248 cases; 3608 controls | Sweden and Norway (Scandinavian/European) | Rare CNVs ≥ 30 kb; genotype array CNV calling. |

| [16] | Abdallah et al., 2025 | De novo CNVs from WES (paediatric OCD) | 183 OCD trio families; 771 control families | Multi-site; ancestry described as diverse in secondary reports | CNV calling from WES; focus on de novo CNVs. |

| [18] | Cappi et al., 2020 | De novo damaging coding variants (trio exomes) | 222 OCD trios; 855 unaffected control trios (QC subsets: 184/777) | Multi-site; ancestry not fully specified in abstract | Overlap with Tourette syndrome and autism genes. |

| [19] | Halvorsen et al., 2021 | Whole-exome sequencing (rare coding variants) | Total 1313 cases (587 trios, 41 quartets, 644 singletons); case–control: 1263 cases vs. 11,580 controls | Diverse ancestry (multi-cohort) | Suggestive SLITRK5 signal; loss-of-function burden in vulnerable genes. |

| [20] | Cappi et al., 2016 | WES (de novo coding variants; pilot) | 20 OCD trios | Not reported in abstract (multi-site clinical cohorts) | Early WES trio study in OCD. |

| [21] | Lin et al., 2022 | Whole-genome sequencing (de novo variants) | 53 parent-offspring families (paediatric-onset OCD probands) | China (Shanghai clinical cohort; likely Han Chinese) | De novo variants implicating chromatin modification pathways. |

| [29] | Stewart et al., 2013 | GWAS (case–control + family-based) | 1465 cases; 5557 controls; 400 trios | European ancestry + Afrikaner (South Africa) + Ashkenazi Jewish (multi-ancestry cohort) | Genotyping arrays; first GWAS in OCD. |

| [33] | Burton et al., 2021 | GWAS of paediatric OC traits (community cohort) | 5018 unrelated children | Predominantly Caucasian/European ancestry (Canada; TOCS cohort) | Trait-based GWAS (symptom dimensions), not clinical OCD diagnosis. |

| [34] | McGrath et al., 2014 | CNV analysis (cross-disorder OCD/TS) | 1613 OCD cases; 1789 controls (plus 1086 TS cases) | Multi-site; ancestry not uniformly reported in abstract | Large, rare CNVs > 500 kb; cross-disorder design. |

| [38] | Yue et al., 2016 | Epigenome-wide DNA methylation (blood; 450K) | 65 cases; 96 controls | China (clinical sample; likely Han Chinese) | Illumina 450K; 8417 differentially methylated probes reported. |

| [39] | D’Addario et al., 2016 | Candidate methylation (OXTR gene) | 42 cases; 31 controls | Italy (European clinical sample) | OXTR methylation/hydroxymethylation in blood; exploratory candidate approach. |

| [41] | Schiele et al., 2022 | EWAS (blood; EPIC) | 76 cases; 76 controls | European ancestry | Illumina EPIC array; epigenome-wide differential methylation. |

| [42] | Campos-Martin et al., 2023 | Epigenome-wide analysis (blood; EPIC) | 185 cases; 199 controls | Germany (European) | Multi-site German recruitment; methylome profiles linked to OCD. |

| [43] | Hoffler et al., 2025 | MWAS (saliva; EPICv2; preprint) | 414 cases; 384 controls | Scandinavia (likely Norway; clinical cohorts) | Saliva DNA methylation; EPICv2 (Illumina) platform. |

| [45] | Yue et al., 2020 | miRNA candidate biomarker study (plasma) | 30 cases; 32 controls | China | miR-132 and miR-134 expression; case–control design. |

| [46] | Aydin et al., 2022 | miRNA and treatment resistance (SSRI) | 100 cases; 50 controls | Turkey | Assessed whether miRNA expression predicts SSRI treatment resistance. |

| [47] | Korkmaz et al., 2025 | miRNA + monoamine markers (female-only) | 22 cases; 20 controls (female) | Turkey | Female-only sample; serotonin/dopamine activity plus miRNAs. |

| [48] | Altunoz et al., 2025 | TGF-beta signalling + miR-132 (serum) | 48 cases; 48 controls | Not explicitly reported in abstract | Integrated cytokine (TGF-beta) and miRNA measures. |

| [49] | Aydin et al., 2025 | Executive functions + miRNA (case–control) | 70 cases; 35 controls | Turkey | Cognitive testing alongside miRNA measures. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bernoni d’Aversa, F.; Gennarelli, M. Genetics and Epigenetics of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Genes 2026, 17, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020189

Bernoni d’Aversa F, Gennarelli M. Genetics and Epigenetics of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Genes. 2026; 17(2):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020189

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernoni d’Aversa, Federico, and Massimo Gennarelli. 2026. "Genetics and Epigenetics of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder" Genes 17, no. 2: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020189

APA StyleBernoni d’Aversa, F., & Gennarelli, M. (2026). Genetics and Epigenetics of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Genes, 17(2), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020189