Functional Genome Prediction and Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling of the Rhizobacteria Serratia liquefaciens Strain UNJFSC002

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genomic Data Collection and Assembly

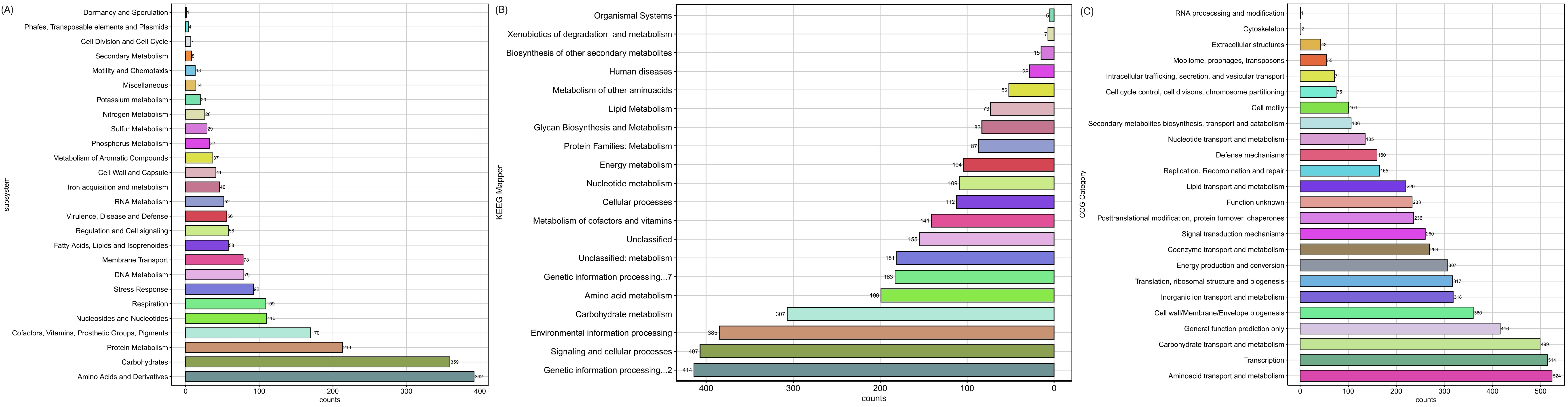

2.2. Genome Assembly, Annotation and Functional Analysis

2.3. Phylogenetic Tree Analysis, Comparative Genome and Pan Genome Analysis

2.4. Computational Phenotyping

2.5. Genome-Scale Metabolic Models Network S. liquefaciens Cepa UNJFSC002

2.6. Screening for Plant-Growth-Promoting Traits

3. Results

3.1. Genomic Data Collection and Assembly of S. liquefaciens Strain UNJFSC002

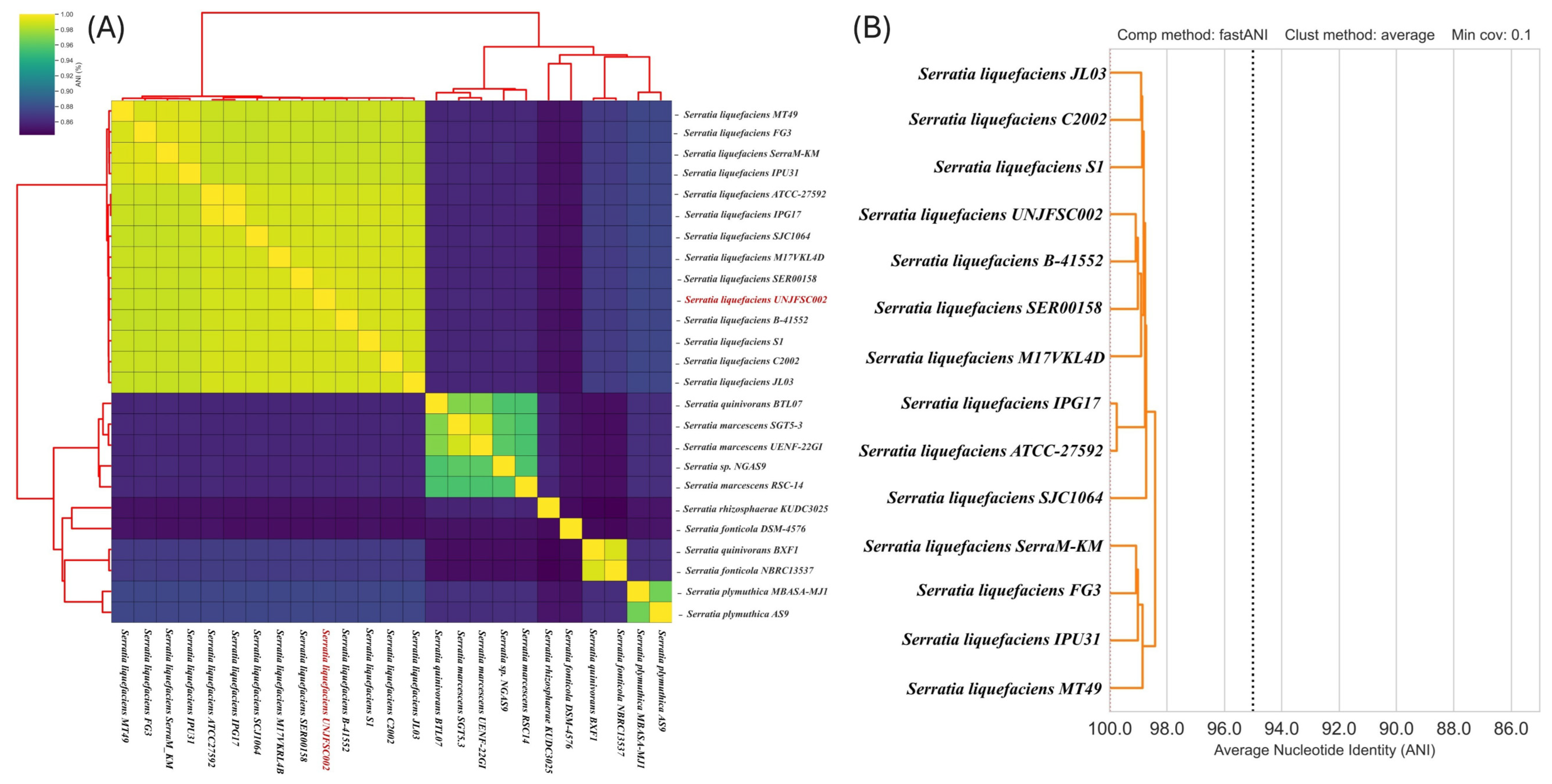

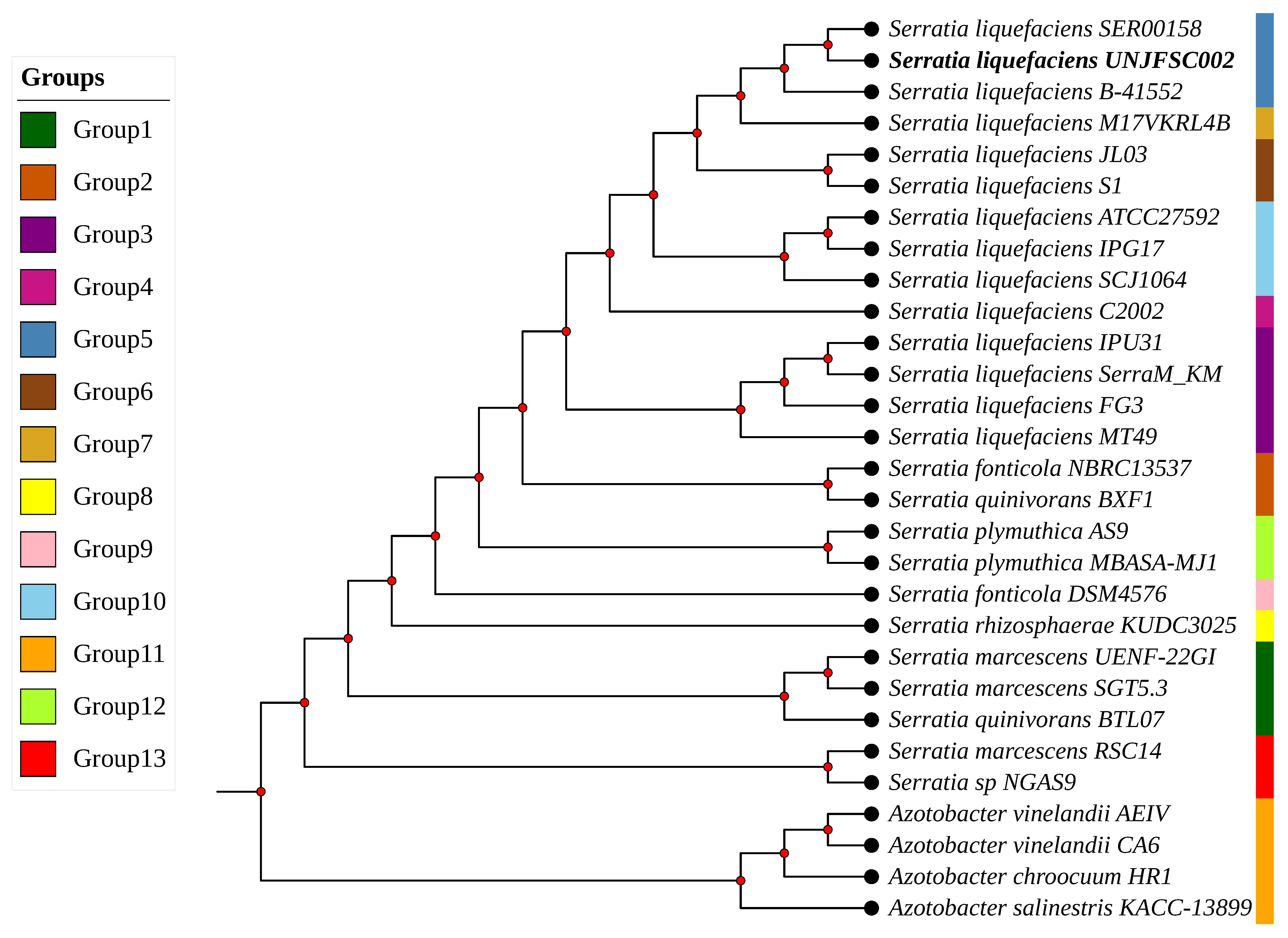

3.2. Comparative Analysis of the Complete Genome and Phylogeny

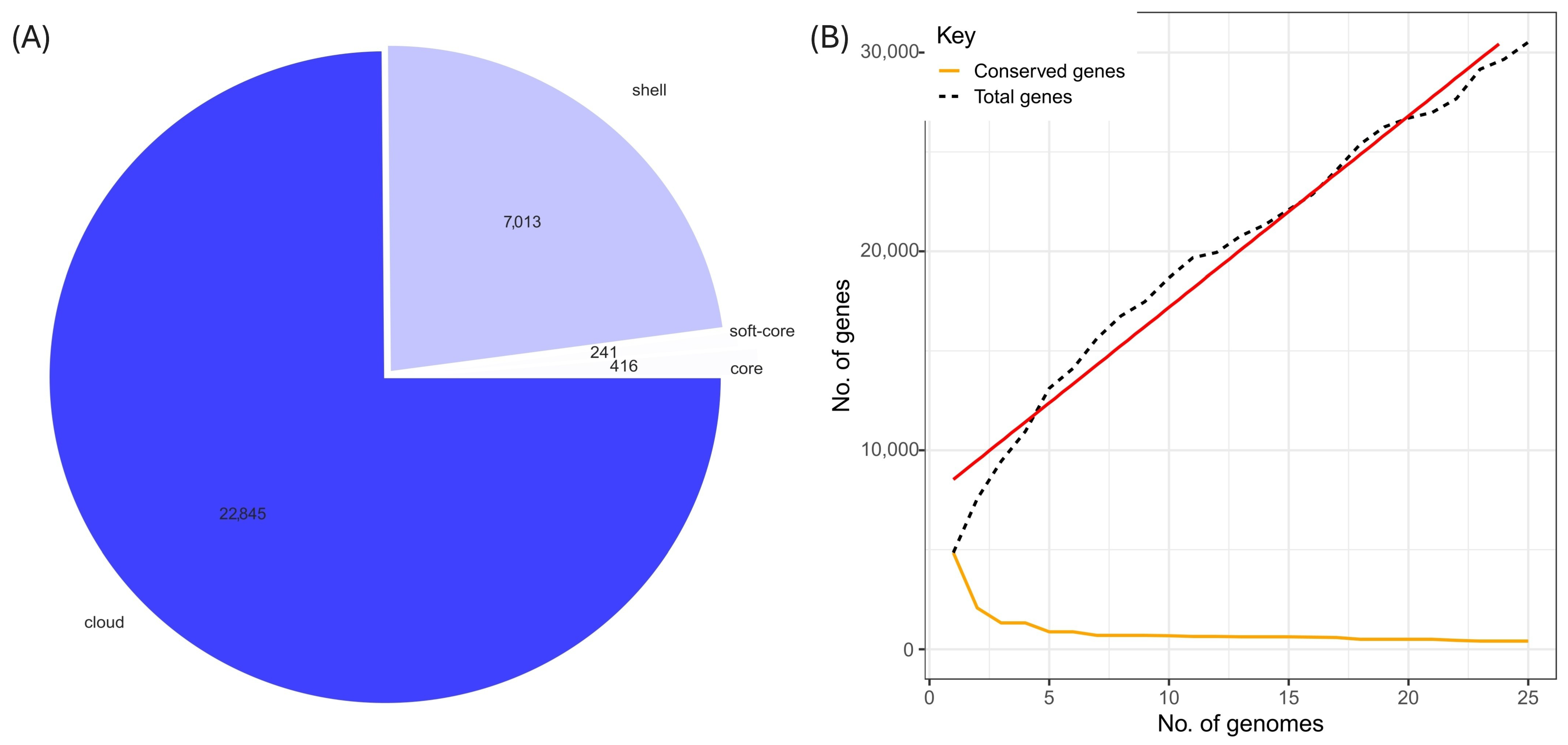

3.3. Comparative Analysis of the Pangenome of S. liquefaciens UNJFSC002

3.4. Computational Phenotyping

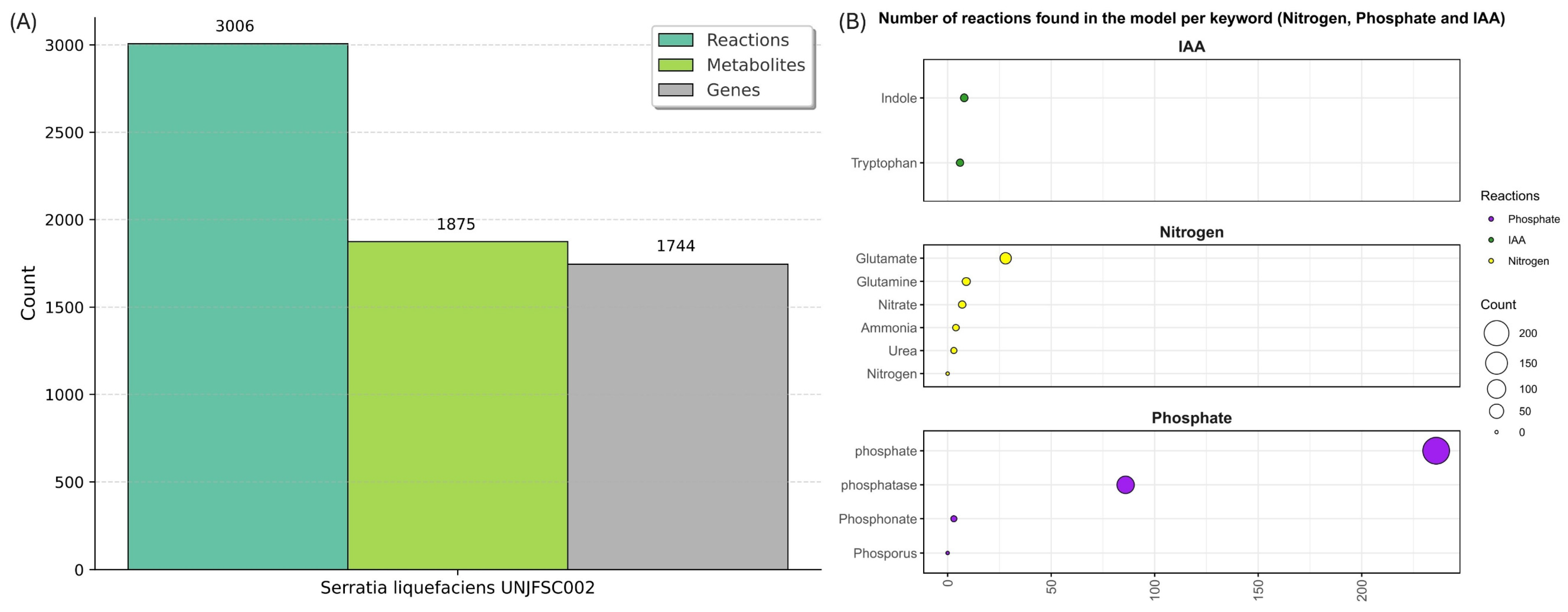

3.5. Top-Down Reconstruction Metabolics Model Strain UNJFSC002

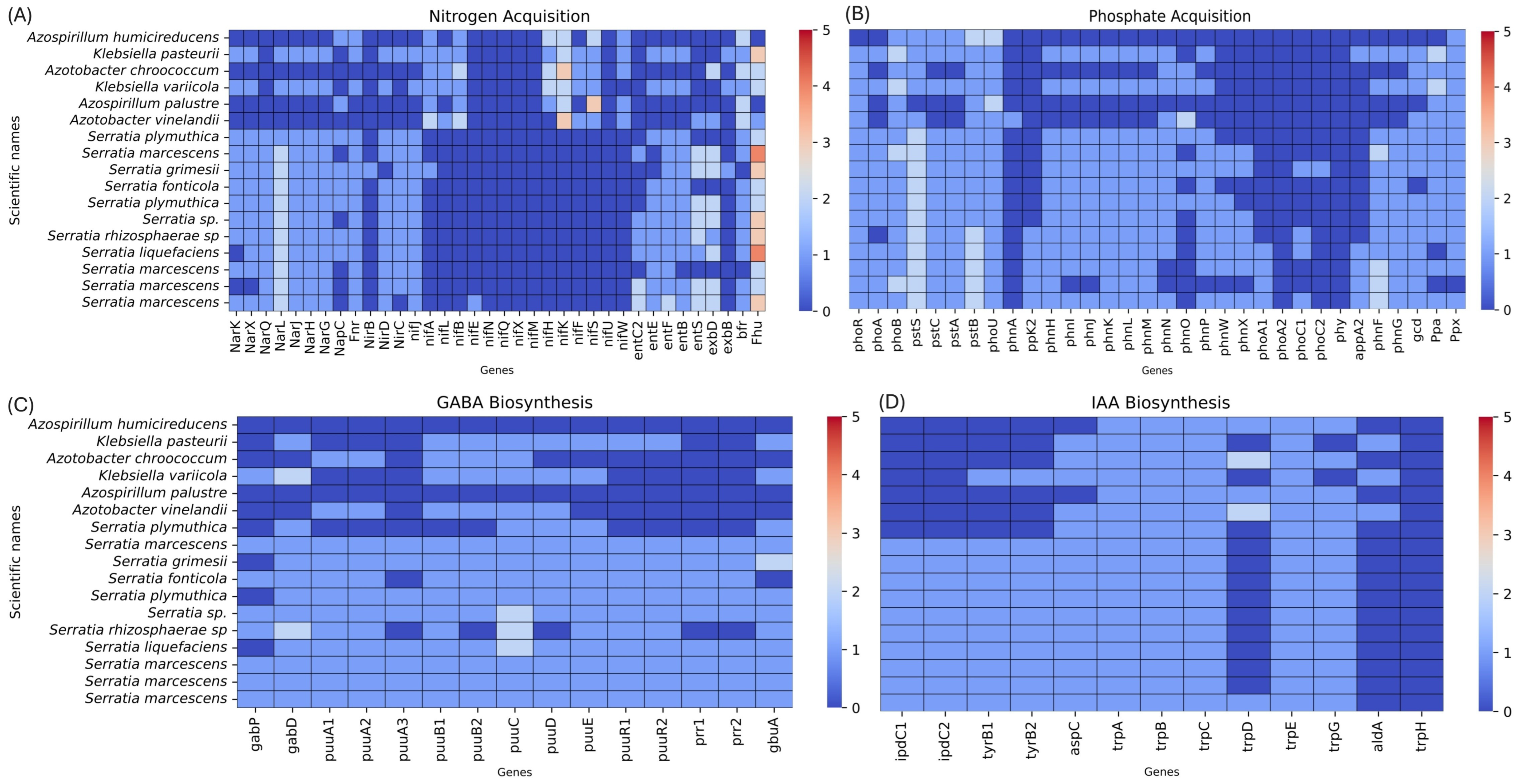

3.6. Characterization of Strain PGPR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martínez, O.A.; Encina, C.; Tomckowiack, C.; Droppelmann, F.; Jara, R.; Maldonado, C.; Muñoz, O.; García-Fraile, P.; Rivas, R. Serratia strains isolated from the rhizosphere of raulí (Nothofagus alpina) in volcanic soils harbour PGPR mechanisms and promote raulí plantlet growth. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2018, 18, 804–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Rodríguez, M.; Almaraz-Suárez, J.J.; Vázquez-Vázquez, C.; Angulo-Castro, A.; Ríos-Vega, M.E.; González-Mancilla, A. Effect of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on the growth and yield of jalapeño pepper. Rev. Mex. De Cienc. Agrícolas 2022, 13, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M.F.; Becerra-Rivera, V.A. The biosynthesis and functions of polyamines in the interaction of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria with plants. Plants 2023, 12, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, B.R. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: Mechanisms and applications. Scientifica 2012, 2012, 963401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backer, R.; Rokem, J.S.; Ilangumaran, G.; Lamont, J.; Praslickova, D.; Ricci, E.; Subramanian, S.; Smith, D.L. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: Context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Wohlleben, W. Polyamine and ethanolamine metabolism in bacteria as an important component of nitrogen assimilation for survival and pathogenicity. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.Y.; Cho, K.S. Isolation and characterization of a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium, Serratia sp. SY5. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 19, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Viveros, O.; Jorquera, M.A.; Crowley, D.E.; Gajardo, G.; Mora, M.L. Mechanisms and practical considerations involved in plant growth promotion by rhizobacteria. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2010, 10, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myo, E.M.; Ge, B.; Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Ma, T.; Liu, Y. Indole-3-acetic acid production by Streptomyces fradiae NKZ-259 and its formulation to enhance plant growth. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, R.; Kumar, V.; Gupta, P.; Chandra, A. Potential use of Solanum lycopersicum and plant growth promoting rhizobacterial (PGPR) strains for the phytoremediation of endosulfan stressed soil. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharucha, U.; Patel, K.; Trivedi, U.B. Optimization of Indole Acetic Acid Production by Pseudomonas putida UB1 and its Effect as Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria on Mustard (Brassica nigra). Agric. Res. 2013, 2, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, R.R.; Mali, G.V.; Waghmare, S.R.; Nadaf, N.H.; Nimbalkar, M.S.; Sonawane, K.D. Impact of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria Serratia nematodiphila RGK and Pseudomonas plecoglossicida RGK on secondary metabolites of turmeric rhizome. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 47, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouremani, N.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Silini, A.; Bouket, A.C.; Luptakova, L.; Alenezi, F.N.; Baranov, O.; Belbahri, L. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR): A Rampart against the Adverse Effects of Drought Stress. Water 2023, 15, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawaa, A.; Hichem, H.; Labidi, S.; Ben, F.J.; Mhadhbi, H.; Nceur, D. Influence of biofertilizers on potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) growth and physiological modulations for water and fertilizers managing. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 174, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeolu, M.; Alnajar, S.; Naushad, S.; Radhey, S.; Gupta, R.S. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: Proposal for Enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. Nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morganellaceae fam. nov., and Budviciaceae fam. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 5575–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkova, I.; Wróbel, B.; Dobrzyński, J. Serratia spp. as plant growth-promoting bacteria alleviating salinity, drought, and nutrient imbalance stresses. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1342331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, J.; Hao, X.; Feng, G.; Shen, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, Z. Serratia marcescens LYGN1 Reforms the Rhizosphere Microbial Community and Promotes Cucumber and Pepper Growth in Plug Seedling Cultivation. Plants 2024, 13, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessì, A.; Puddu, M.; Testa, M.; Marcialis, M.A.; Pintus, M.C.; Fanos, V. Serratia marcescens infections and outbreaks in neonatal intensive care units. J. Chemother. 2009, 21, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.M.; Tisa, L.S. Friend or foe? A review of the mechanisms that drive Serratia towards diverse lifestyles. Can. J. Microbiol. 2013, 59, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreo, E.; Altier, N. Pangenome of Serratia marcescens strains from nosocomial and environmental origins reveals different populations and the links between them. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordstedt, N.P.; Jones, M.L. Genomic analysis of Serratia plymuthica MBSA-MJ1: A plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria that improves water stress tolerance in greenhouse ornamentals. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 653556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, U.; Khatri, I.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, L.; Sharma, D.; Subramanian, S.; Saini, A.K. Draft Genome Sequence of a Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacterium, Serratia fonticola Strain AU-P3(3). Genome Announc. 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleyn, M.S.; Akinyemi, M.O.; Bezuidenhout, C.; Adeleke, R.A. Draft genome sequences of three Serratia liquefaciens strains isolated from vegetables in South Africa. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2025, 14, e00772-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.L.; Constantinidou, C.; Alam, M.T. Applications of genome-scale metabolic models to investigate microbial metabolic adaptations in response to genetic or environmental perturbations. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbad439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, J.D.; Thiele, I.; Palsson, B.Ø. What is flux balance analysis? Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, I.; Palsson, B.Ø. A protocol for generating a high-quality genome-scale metabolic reconstruction. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 93–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakır, T.; Khatibipour, M.J. Metabolic network discovery by top-down and bottom-up approaches and paths for reconciliation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2014, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twycross, J.; Band, L.R.; Bennett, M.J.; King, J.R.; Krasnogor, N. Stochastic and deterministic multiscale models for systems biology: An auxin-transport case study. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkelmann, F.; Laubenbacher, R. Boolean models of bistable biological systems. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0912.2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzo, V.; Galperin, M.Y. Microbial systems biology: Bottom up and top down. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 33, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Orešič, M. Integrating Omics Data in Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling: A Methodological Perspective for Precision Medicine. Metabolites 2023, 13, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, F.; Nogales, J. Toward merging bottom–up and top–down model-based designing of synthetic microbial communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 69, 102169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, B.R.; Timmerman, L.E.; Daringer, N.M.; Leonard, J.N.; Jewett, M.C. Biology by design: From top to bottom and back. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 232016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Grados, P.M.; Arbizu, C.I.; Castillo, G.; Camel, V.; Conteras-Liza, S. Draft genome sequence of the Serratia liquefaciens strain UNJFSC002, isolated from the soil of a potato field of the Bicentenaria variety. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2025, 14, e00495-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, C.A.; Durand, Z.H.; Rodriguez-Grados, P.M.; Tineo, D.L.; Takei, D.H.; Arbizu, C.I.; Contreras-Liza, S. The Growth-Promoting Ability of Serratia liquefaciens UNJFSC002, a Rhizobacterium Involved in Potato Production. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data [Online]. 2010. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, F.A.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Ioannidis, P.; Kriventseva, E.V.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO online supplementary information: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3210–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R. Classifying prokaryotic genomes using thein microbial genomes atlas (MiGA) webserver. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seemann, T. Barrnap 0.9: Rapid Ribosomal RNA Prediction [Software]. 2013. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST Server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laslett, D.; Canbäck, B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, Y.; Itoh, M.; Okuda, S.; Yoshizawa, A.C.; Kanehisa, M. KAAS: An automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldbauer, R.; Gosch, L.; Lüftinger, L.; Hyden, P.; Flexer, A.; Rattei, T. DeepNOG: Fast and accurate protein orthologous group assignment. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 5304–5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumsille, A.; Durán, R.E.; Rodríguez-Delherbe, A.; Saona-Urmeneta, V.; Cámara, B.; Seeger, M.; Araya, M.; Jara, N.; Buil-Aranda, C. GenoVi, an open-source automated circular genome visualizer for bacteria and archaea. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1010998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Na, S.-I.; Kim, D.; Chun, J. UBCG2: Up-to-date bacterial core genes and pipeline for phylogenomic analysis. J. Microbiol. 2021, 59, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R.; Teeling, E. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, L.; Harrington, B.; Cock, P.; Davey, R.; Waters, N.; Brankovics, B.; Esen, Ö. Pyani: Whole-Genome Classification Using Average Nucleotide Identity; University of Strathclyde: Glasgow, Scotland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olm, M.R.; Brown, C.T.; Brooks, B.; Banfield, J.F. dRep: A tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2864–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.G.; Fookes, M.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaskom/Seaborn, version 0.8.1. [Software]. Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, September 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in python. SciPy 2010, 445, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, D.; Andrejev, S.; Tramontano, M.; Patil, K.R. Fast automated reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models for microbial species and communities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 7542–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Z.A.; Lu, J.S.; Dräger, A.; Miller, P.C.; Federowicz, S.; Lerman, J.A.; Ebrahim, A.; Palsson, B.O.; Lewis, N.E. BiGG Models: A platform for integrating, standardizing, and sharing genome-scale models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D515–D522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernandez-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Römer, M.; Eichner, J.; Dräger, A.; Wrzodek, C.; Wrzodek, F.; Zell, A. ZBIT Bioinformatics Toolbox: A web-platform for systems biology and expression data analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieven, C.; Beber, M.E.; Olivier, B.G.; Bergmann, F.T.; Ataman, M.; Babaei, P.; Bartell, J.A.; Blank, L.M.; Chauhan, S.; Correia, K.; et al. MEMOTE for standardized genome-scale metabolic model testing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Z.A.; Dräger, A.; Ebrahim, A.; Sonnenschein, N.; Lewis, N.E.; Palsson, B.O. Escher: A web application for building, sharing, and embedding data-rich visualizations of biological pathways. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.; Liao, J.C.; Palsson, B.Ø. COBRApy: COnstraints-Based Reconstruction and Analysis for Python. BMC Syst. Biol. 2013, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, C.S. An efficient microbiological growth medium for screening phosphate solubilizing microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 170, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, D.; Gómez, R.; Garrido, M.; Bonilla, R. Inoculation with plant growth promoting bacteria on tomato under greenhouse conditions. Rev. Mex. De Cienc. Agrícolas 2012, 3, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga Dávila, D.E. Manual de microbiología agrícola. Rhizobium, PGPRs, Indicadores de Fertilidad e Inocuidad; Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina: Lima, Peru, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Samira, M.; Mohammad, R.; Gholamreza, G. Carboxymethylcellulase and Filter-paperase Activity of New Strains Isolated from Persian Gulf. Microbiol. J. 2011, 1, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-R, L.M.; Conrad, R.E.; Viver, T.; Feistel, D.J.; Lindner, B.G.; Venter, S.N.; Orellana, L.H.; Amann, R.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Konstantinidis, K.T. An ANI gap within bacterial species that advances the definitions of intra-species units. mBio 2023, 15, e02696-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.S.; Thakur, S.; Ye, M.; Monteil-Rivera, F.; Pan, Y.; Qin, W.; Yang, T.C. Uncovering the lignin-degrading potential of Serratia quinivorans AORB19: Insights from genomic analyses and alkaline lignin degradation. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Xu, Y.; Feng, X. DeepMetabolism: A deep learning system to predict phenotype from genome sequencing. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.03094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Córdoba, L.K.; Chande, A.T.; Rishishwar, L.; Mayer, L.W.; Valderrama-Aguirre, L.C.; Valderrama-Aguirre, A.; Gaby, J.C.; Kostka, J.E.; Jordan, I.K. Genomic characterization and computational phenotyping of nitrogen-fixing bacteria isolated from Colombian sugarcane fields. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Chen, Y.; Gustafsson, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xing, X. Genome-scale metabolic models applied for human health and biopharmaceutical engineering. Quant. Biol. 2023, 11, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, P.D.; Billington, R.; Caspi, R.; A Fulcher, C.; Latendresse, M.; Kothari, A.; Keseler, I.M.; Krummenacker, M.; E Midford, P.; Ong, Q.; et al. The BioCyc collection of microbial genomes and metabolic pathways. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.S.; DeJongh, M.; Best, A.A.; Frybarger, P.M.; Linsay, B.; Stevens, R.L. High-throughput generation, optimization and analysis of genome-scale metabolic models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; Viteri, G.; Gong, C.; Lorente, P.; Fabregat, A.; Sidiropoulos, K.; Cook, J.; Gillespie, M.; Haw, R.; et al. The Reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, S.; Tran, V.D.; Mehl, F.; Ibberson, M.; Pagni, M. MetaNetX/MNXref: Unified namespace for metabolites and biochemical reactions in the context of metabolic models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, J.; Owen, G.; Dekker, A.; Ennis, M.; Kale, N.; Muthukrishnan, V.; Turner, S.; Swainston, N.; Mendes, P.; Steinbeck, C. ChEBI in 2016: Improved services and an expanding collection of metabolites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, I.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Sikandar, S.; Shahzad, S. Plant beneficial endophytic bacteria: Mechanisms, diversity, host range and genetic determinants. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 221, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliute, I.; Buzaite, O.; Baniulis, D.; Stanys, V. Bacterial endophytes in agricultural crops and their role in stress tolerance: A review. CABI Rev. 2015, 4, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, G.; Moreno-Hagelsieb, G.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.C.; Glick, B.R. Plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 183, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaresan, N.; Senthil Kumar, M.; Annapurna, K.; Kumar, K.; Sankaranarayanan, A. (Eds.) Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology: Bacteria and Fungi, 1st ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dastager, S.G.; Deepa, C.K.; Pandey, A. Potential plant growth-promoting activity of Serratia nematodiphila NII-0928 on black pepper (Piper nigrum L.). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Jha, P.N. The multifarious PGPR Serratia marcescens CDP-13 augments induced systemic resistance and enhanced salinity tolerance of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Park, G.-S.; Asaf, S.; Hong, S.-J.; Jung, B.K.; Shin, J.-H. Complete genome analysis of Serratia marcescens RSC-14: A plant growth-promoting bacterium that alleviates cadmium stress in host plants. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Khatun, A.; Gupta, D.R.; Surovy, M.Z.; Rahman, M.M.; Mahmud, N.U.; Emes, R.D.; Warry, A.; West, H.M.; Clarke, M.L.; et al. Whole-genome sequence of a plant growth-promoting strain, Serratia marcescens BTL07, isolated from the rhizoplane of Capsicum annuum L. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020, 9, e01484-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, M.A.; Mohamed, E.T. Characterization of Serratia marcescens (OK482790)’ prodigiosin along with in vitro and in silico validation for its medicinal bioactivities. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matteoli, F.P.; Passarelli-Araujo, H.; Reis, R.J.A.; da Rocha, L.O.; de Souza, E.M.; Aravind, L.; Olivares, F.L.; Venancio, T.M. Genome sequencing and assessment of plant growth-promoting properties of a Serratia marcescens strain isolated from vermicompost. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Borker, S.S.; Thakur, A.; Thapa, P.; Kumar, S.; Mukhia, S.; Anu, K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Kumar, S. Physiological and genomic evidence supports the role of Serratia quinivorans PKL:12 as a biopriming agent for the biohardening of micropropagated Picrorhiza kurroa plantlets in cold regions. Genomics 2021, 113, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.; Yu, X.; Ye, Z. Biosynthetic pathways and functions of indole-3-acetic acid in microorganisms. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsigian, C.J.; Pusarla, N.; McConn, J.L.; Yurkovich, J.T.; Dräger, A.; Palsson, B.O.; King, Z. BiGG Models 2020: Multi-strain genome-scale models and expansion across the phylogenetic tree. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D402–D406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queenan, A.M.; Bush, K. Carbapenemases: The Versatile β-Lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 440–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L.H.; Jensen, L.B.; Sørensen, H.I.; Sørensen, S.J. Substrate specificity of the OqxAB multidrug resistance pump in Escherichia coli and selected enteric bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, G.A. AmpC β-Lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | NCBI Reference Sequence | Country | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. plymuthica AS9 | NC_015567.1 | Sweden | Rhizosphere |

| S. liquefaciens ATCC27592 | CP006252.1 | Unknown | N/A |

| S. liquefaciens B-41552 | NZ_MQMW00000000.1 | United States | Ground beef |

| S. marcescens BTL07 | NZ_WNKC00000000.1 | Bangladesh | Capsicum annum rhizoplane |

| S. grimesii BXF1 | NZ_LT883155.1 | Portugal | Diseased Pinus pinaster |

| S. liquefaciens C2002 | NZ_JACAPD010000021.1 | Netherlands | Symptomatic mushroom tissue |

| S. fonticola DSM4576 | NZ_CP011254.1 | Malaysia | Water |

| S. liquefaciens FG3 | NZ_CP033893.1 | Brazil | Flower of Stachytarpheta glabra |

| S. liquefaciens IPG17 | NZ_JAQNAS000000000.1 | United States | Imported Fresh Produce 14 |

| S. liquefaciens IPU31 | NZ_JAWQEN000000000.1 | United States | N/A |

| S. liquefaciens JL03 | NZ_QCYZ00000000.1 | China | Cattle |

| S. rhizosphaerae KUDC3025 | NZ_CP041764.1 | South Korea | Rhizospheric soil |

| S. liquefaciens M17VKL4B | NZ_JAXOWE000000000.1 | South Africa | Leaves |

| S. plymuthica MBSA-MJ1 | NZ_JADCNO000000000.1 | United States | Environment |

| S. liquefaciens MT49 | NZ_CP061082.1 | United States | Groundwater from well |

| S. grimesii NBRC13537 | NZ_BCTT01000040.1 | Japan | N/A |

| Serratia sp. NGAS9 | NZ_CP047605.1 | Germany | Rhizosphere soil |

| S. marcescens RSC-14 | NZ_CP012639.1 | South Korea | Root of Solanum nigrum |

| S. marcescens S1 | NZ_JADKMB000000000.1 | Spain | Human disease |

| S. liquefaciens SER00158 | NZ_JADTPQ000000000.1 | United States | Wound human |

| S. liquefaciens SerraM_KM | NZ_JAHQRD000000000.1 | Greece | Sea bream |

| S. marcescens SGT5.3 | NZ_JAJFEW000000000.1 | United Kingdom | Fruit |

| S. liquefaciens SJC1064 | NZ_CAMKUI000000000.1 | United States | Bloodstream |

| S. marcescens UENF-22GI | NZ_LIAI00000000.1 | Brazil | Vermicompost |

| S. liquefaciens UNJFSC002 | NZ_JBAKHJ000000000.1 | Peru | Bicentennial potato soil |

| Quality Control FastQ | Results |

|---|---|

| High-quality reads | 10,613,744 (99.760%) |

| Low-quality reads | 19,324 (0.182%) |

| Contaminated reads | 336 (0.003%) |

| Short reads | 5852 (0.055%) |

| Trimmed adaptors | Yes |

| Completeness | 100 |

| Contamination | 1.90% |

| GC% | 55.33 |

| No. of BUSCOs a | 439/1/1/0 |

| Contigs N50/L50 (bp) | 376/7 |

| Name | Gene | Resistance | Product | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. plymuthica AS9 | oqxB11 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB11 | NG_050429.1 |

| S. plymuthica AS9 | qnrB96 | Quinolone | quinolone resistance pentapeptide repeat protein QnrB96 | NG_067167.1 |

| S. plymuthica AS9 | bla-C | Beta-Lactam | class C beta-lactamase | NG_047385.1 |

| S. marcescens BTL07 | oqxB9 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB9 | NG_050458.1 |

| S. marcescens BTL07 | blaSST-1 | Cephalosporin | cephalosporin-hydrolyzing class C beta-lactamase SST-1 | NG_050144.1 |

| S. marcescens BTL07 | tet(41) | Tetracycline | tetracycline efflux MFS transporter Tet(41) | NG_048142.1 |

| S. marcescens BTL07 | aac(6’)_Serra | Aminoglycoside | aminoglycoside 6’-N-acetyltransferase | NG_052196.1 |

| S. quinivorans BXF1 | blaSPR-1 | Carbapenem | putative metallo-beta-lactamase SPR-1 | NG_052102.1 |

| K. variicola DX120E | blaFONA-1 | Beta-Lactam | class A beta-lactamase FONA-1 | NG_049092.1 |

| K. variicola DX120E | oqxB9 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB9 | NG_050458.1 |

| K. variicola DX120E | oqxA6 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter periplasmic adaptor subunit OqxA6 | NG_050424.1 |

| K. variicola DX120E | blaLEN-17 | Beta-Lactam | class A beta-lactamase LEN-17 | NG_049271.1 |

| S. plymuthica MBASA-MJ1 | oqxB17 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB17 | NG_050435.1 |

| S. plymuthica MBASA-MJ1 | bla-C | Beta-Lactam | class C beta-lactamase | NG_047385.1 |

| S. plymuthica MBASA-MJ1 | qnrE1 | Quinolone | quinolone resistance pentapeptide repeat protein QnrE1 | NG_054677.1 |

| K. pasteurii NG13 | fosA_gen | Fosfomycin | FosA family fosfomycin resistance glutathione transferase | NG_047885.1 |

| K. pasteurii NG13 | blaOXY-4-1 | Beta-Lactam | class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamase OXY-4-1 | NG_050613.1 |

| K. pasteurii NG13 | oqxA10 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter periplasmic adaptor subunit OqxA10 | NG_050418.1 |

| K. pasteurii NG13 | oqxB20 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB20 | NG_050439.1 |

| Serratia sp. NGAS9 | oqxB30 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB30 | NG_050450.1 |

| Serratia sp. NGAS9 | blaSRT | Cephalosporin | SRT/SST family class C beta-lactamase | NG_047548.1 |

| Serratia sp. NGAS9 | tet(41) | Tetracycline | tetracycline efflux MFS transporter Tet(41) | NG_048142.1 |

| Serratia sp. NGAS9 | aac(6’)_Serra | Aminoglycoside | aminoglycoside 6’-N-acetyltransferase | NG_052448.1 |

| S. marcescens RSC14 | oqxB25 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB25 | NG_050444.1 |

| S. marcescens RSC14 | aac(6’)_Serra | Aminoglycoside | aminoglycoside 6’-N-acetyltransferase | NG_052468.1 |

| S. marcescens RSC14 | tet(41) | Tetracycline | tetracycline efflux MFS transporter Tet(41) | NG_048142.1 |

| S. marcescens RSC14 | blaSST-1 | Cephalosporin | cephalosporin-hydrolyzing class C beta-lactamase SST-1 | NG_050144.1 |

| S. liquefaciens UNJFSC002 | blaSPR-1 | Carbapenem | putative metallo-beta-lactamase SPR-1 | NG_052102.1 |

| S. liquefaciens UNJFSC002 | oqxB9 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB9 | NG_050458.1 |

| S. liquefaciens UNJFSC002 | bla-C | Beta-Lactam | class C beta-lactamase | NG_047385.1 |

| S. marcescens SGT5.3 | tet(41) | Tetracycline | tetracycline efflux MFS transporter Tet(41) | NG_048142.1 |

| S. marcescens SGT5.3 | blaSST-1 | Cephalosporin | cephalosporin-hydrolyzing class C beta-lactamase SST-1 | NG_050144.1 |

| S. marcescens SGT5.3 | aac(6’)_Serra | Aminoglycoside | aminoglycoside 6’-N-acetyltransferase | NG_052346.1 |

| S. marcescens SGT5.3 | oqxB5 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB5 | NG_050454.1 |

| S. marcescens UENF-22GI | tet(41) | Tetracycline | tetracycline efflux MFS transporter Tet(41) | NG_048142.1 |

| S. marcescens UENF-22GI | blaSST-1 | Cephalosporin | cephalosporin-hydrolyzing class C beta-lactamase SST-1 | NG_050144.1 |

| S. marcescens UENF-22GI | oqxB25 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB25 | NG_050444.1 |

| S. marcescens UENF-22GI | aac(6’)-Ial | Aminoglycoside | aminoglycoside N-acetyltransferase AAC(6’)-Ial | NG_047281.1 |

| K. pasteurii NG13 | fosA_gen | Fosfomycin | FosA family fosfomycin resistance glutathione transferase | NG_047885.1 |

| K. pasteurii NG13 | blaOXY-4-1 | Beta-Lactam | class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamase OXY-4-1 | NG_050613.1 |

| K. pasteurii NG13 | oqxA10 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter periplasmic adaptor subunit OqxA10 | NG_050418.1 |

| K. pasteurii NG13 | oqxB20 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB20 | NG_050439.1 |

| K. variicola DX120E | oqxB9 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter permease subunit OqxB9 | NG_050458.1 |

| K. variicola DX120E | oqxA6 | Phenicol;Quinolone | multidrug efflux RND transporter periplasmic adaptor subunit OqxA6 | NG_050424.1 |

| K. variicola DX120E | blaLEN-17 | Beta-Lactam | class A beta-lactamase LEN-17 | NG_049271.1 |

| Keyword | Reaction Count | Total Flux | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonia | 4 | 318.312751554756 | Nitrogen |

| Nitrate | 7 | 0 | Nitrogen |

| Urea | 3 | 0 | Nitrogen |

| Glutamine | 9 | 246.955109937283 | Nitrogen |

| Glutamate | 28 | 969.168784682527 | Nitrogen |

| Nitrogen | 0 | 0 | Nitrogen |

| Phosphate | 236 | 555.116982396018 | Phosphate |

| Phosphatase | 86 | 196.634440032285 | Phosphate |

| Phosphonate | 3 | 0 | Phosphate |

| Phosphorus | 0 | 0 | Phosphate |

| Indole | 8 | 111.681921901678 | IAA |

| Tryptophan | 9 | 111.681921901678 | IAA |

| In Vitro Test | S. liquefaciens UNJFSC002 |

|---|---|

| Phosphate solubilization | + |

| IAA production | + |

| Biological nitrogen fixation | − |

| Cellulolytic activity | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Andrade Alvarado, C.K.; Honorio Durand, Z.F.; Contreras-Liza, S.E.; Castillo, G.; Guzman Sanchez, W.A.; Takei-Idiaquez, D.H.; Ballen-Gavidia, J.E.; Arbizu, C.I.; Rodriguez-Grados, P.M. Functional Genome Prediction and Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling of the Rhizobacteria Serratia liquefaciens Strain UNJFSC002. Genes 2026, 17, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020169

Andrade Alvarado CK, Honorio Durand ZF, Contreras-Liza SE, Castillo G, Guzman Sanchez WA, Takei-Idiaquez DH, Ballen-Gavidia JE, Arbizu CI, Rodriguez-Grados PM. Functional Genome Prediction and Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling of the Rhizobacteria Serratia liquefaciens Strain UNJFSC002. Genes. 2026; 17(2):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020169

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndrade Alvarado, Cristina Karina, Zoila Felipa Honorio Durand, Sergio Eduardo Contreras-Liza, Gianmarco Castillo, William Andres Guzman Sanchez, Diego Hiroshi Takei-Idiaquez, Julio E. Ballen-Gavidia, Carlos I. Arbizu, and Pedro M. Rodriguez-Grados. 2026. "Functional Genome Prediction and Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling of the Rhizobacteria Serratia liquefaciens Strain UNJFSC002" Genes 17, no. 2: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020169

APA StyleAndrade Alvarado, C. K., Honorio Durand, Z. F., Contreras-Liza, S. E., Castillo, G., Guzman Sanchez, W. A., Takei-Idiaquez, D. H., Ballen-Gavidia, J. E., Arbizu, C. I., & Rodriguez-Grados, P. M. (2026). Functional Genome Prediction and Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling of the Rhizobacteria Serratia liquefaciens Strain UNJFSC002. Genes, 17(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020169