Enhancing Ecological Functions in Chinese Yellow Earth: Metagenomic Evidence of Microbial and Nitrogen Cycle Reassembly by Organic Amendments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Overview

2.2. Plant-Based Organic Amendments and Soil

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Sample Collection and Determination

2.4.1. Sample Collection

2.4.2. Determination Method

2.5. Metagenomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

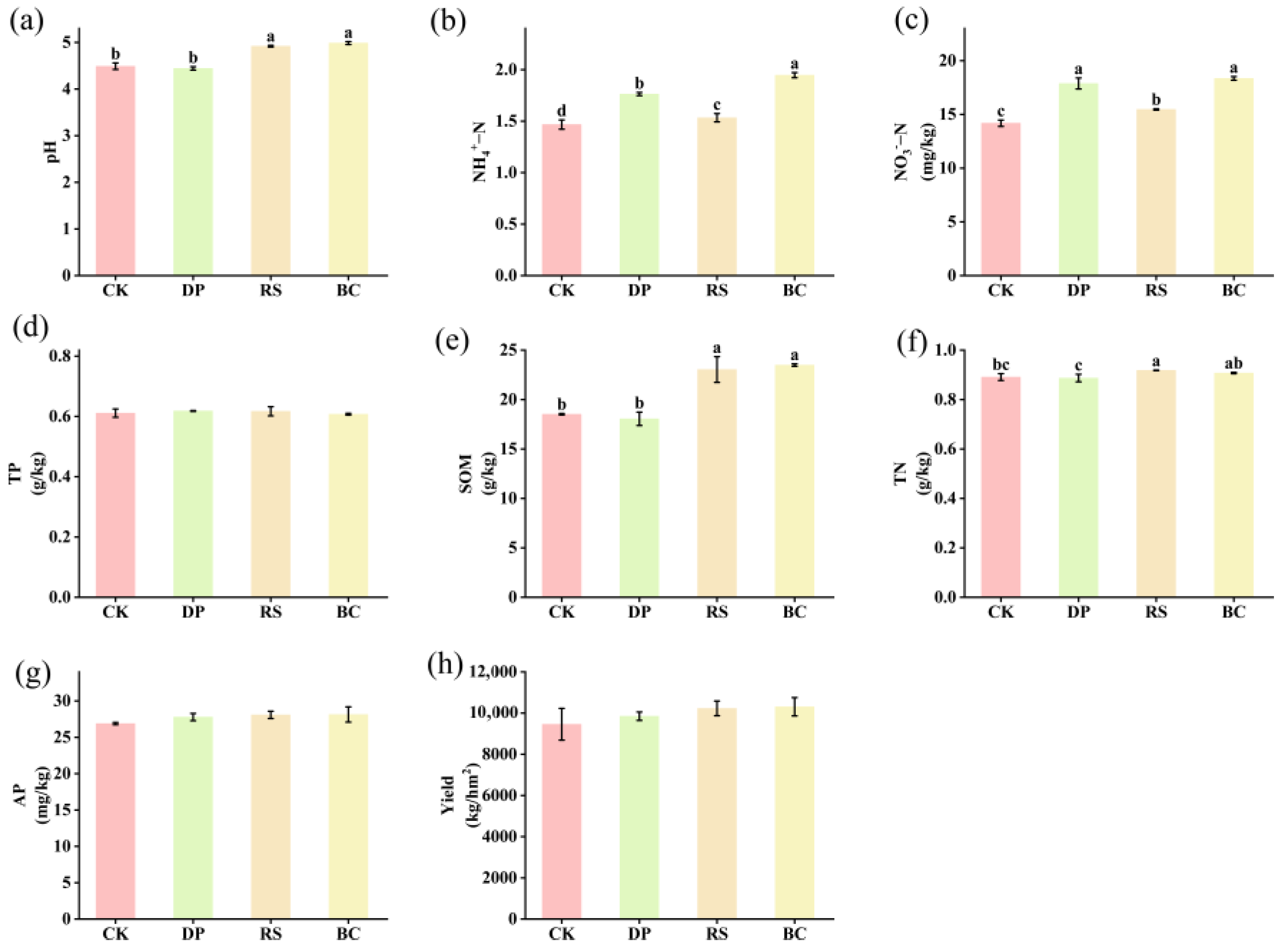

3.1. Soil Nutrient Content and Crop Yield

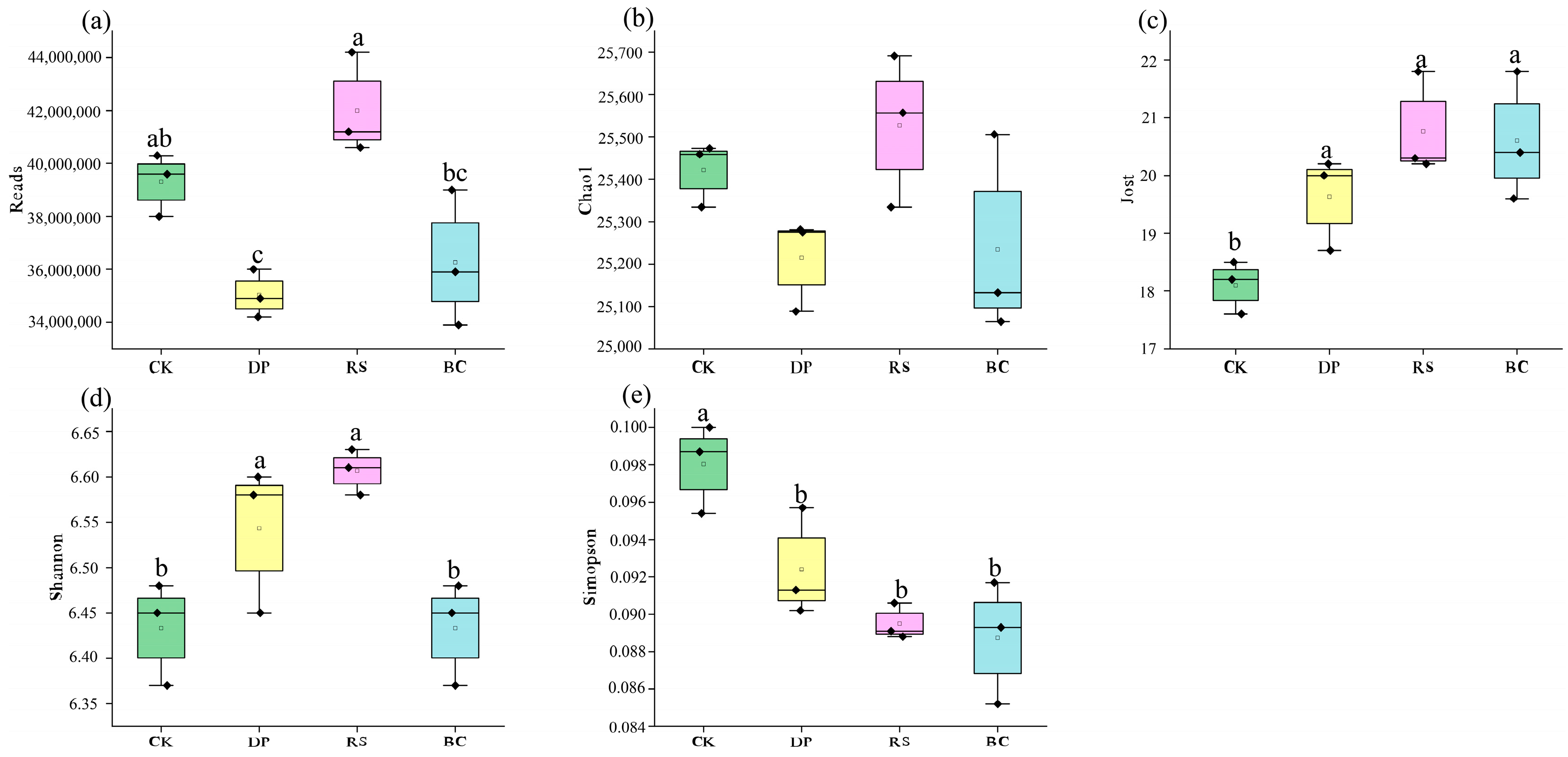

3.2. Changes in Soil Microbial Community Diversity

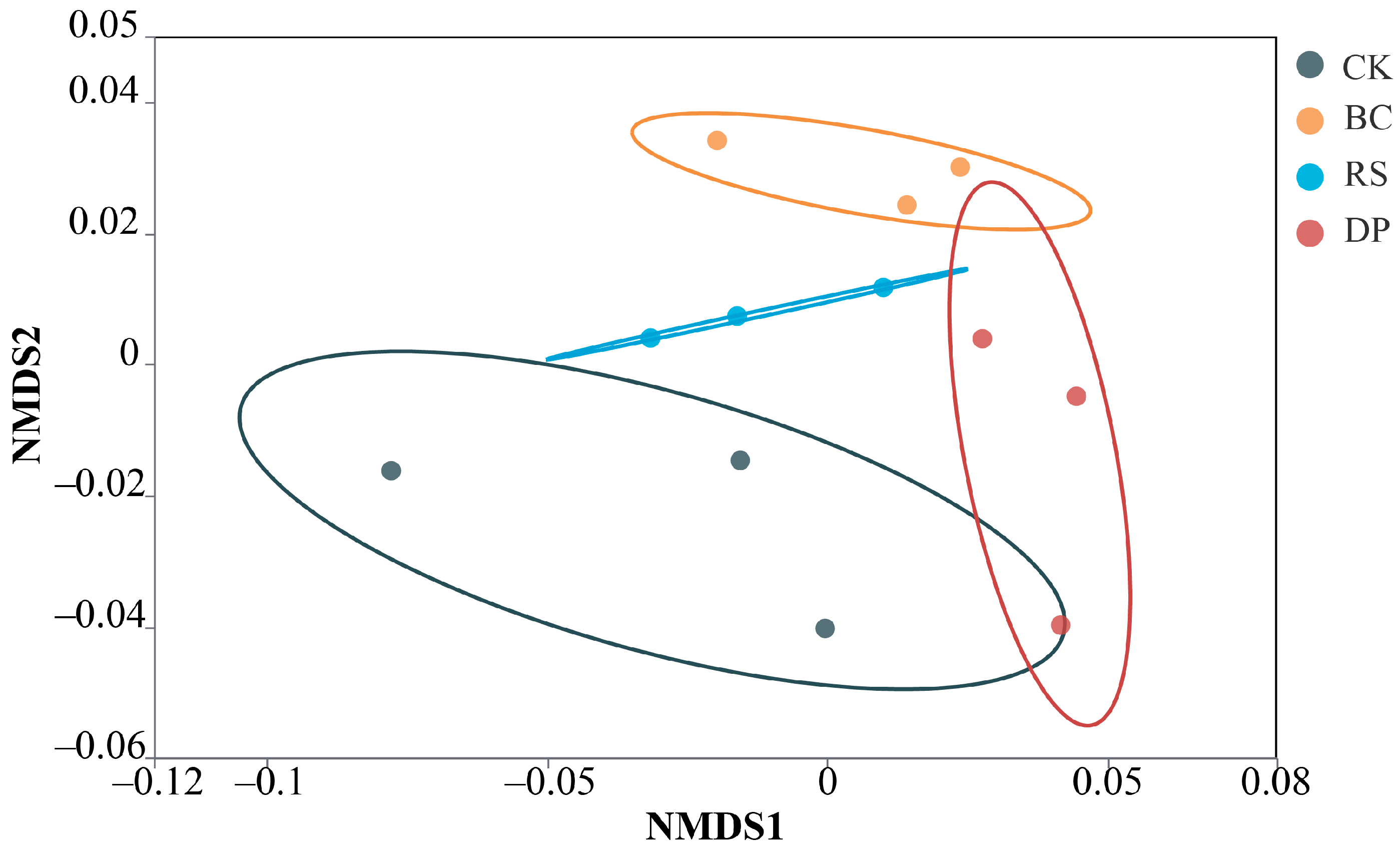

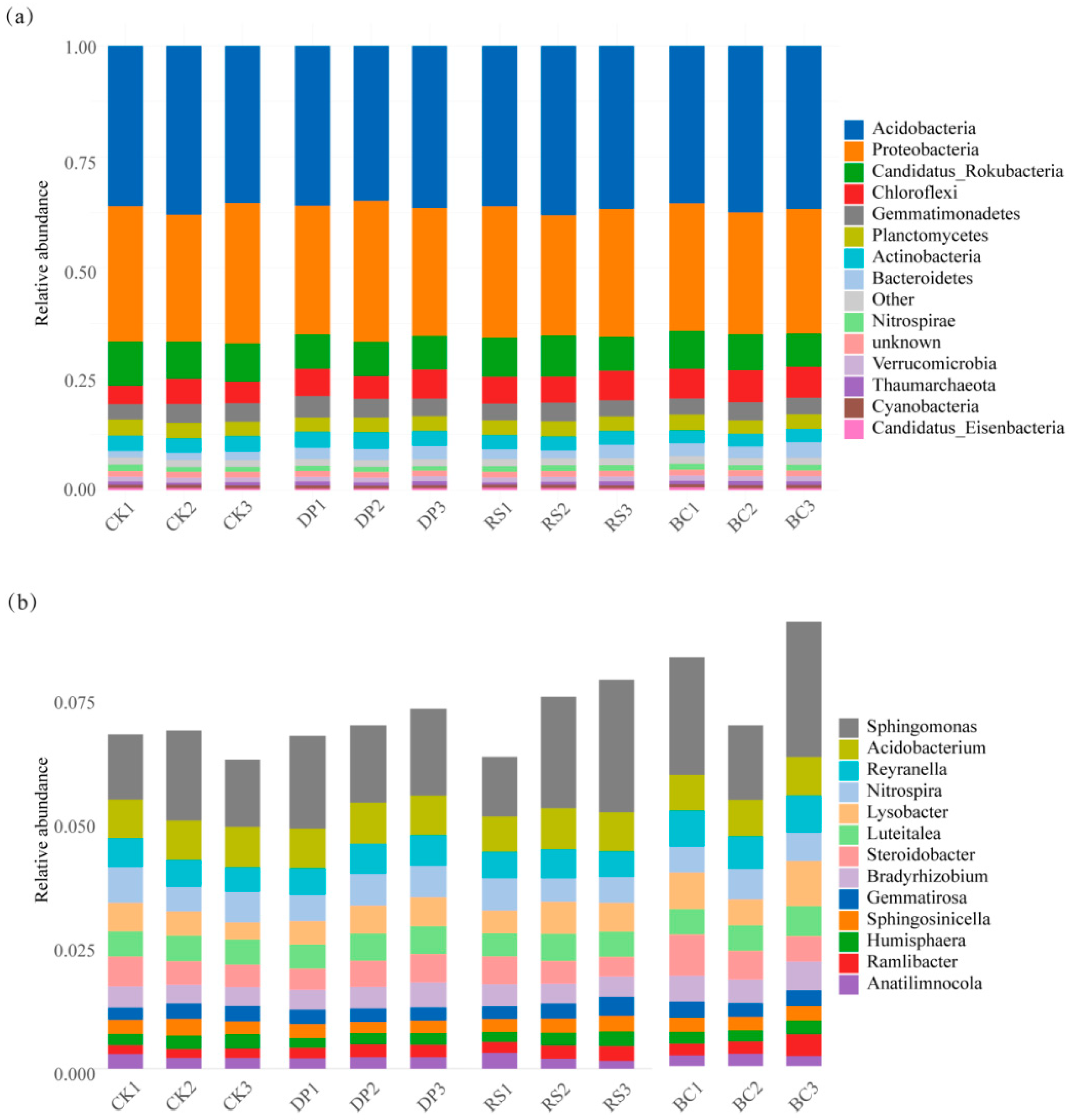

3.3. Organic Amendments Alter Maize Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structure

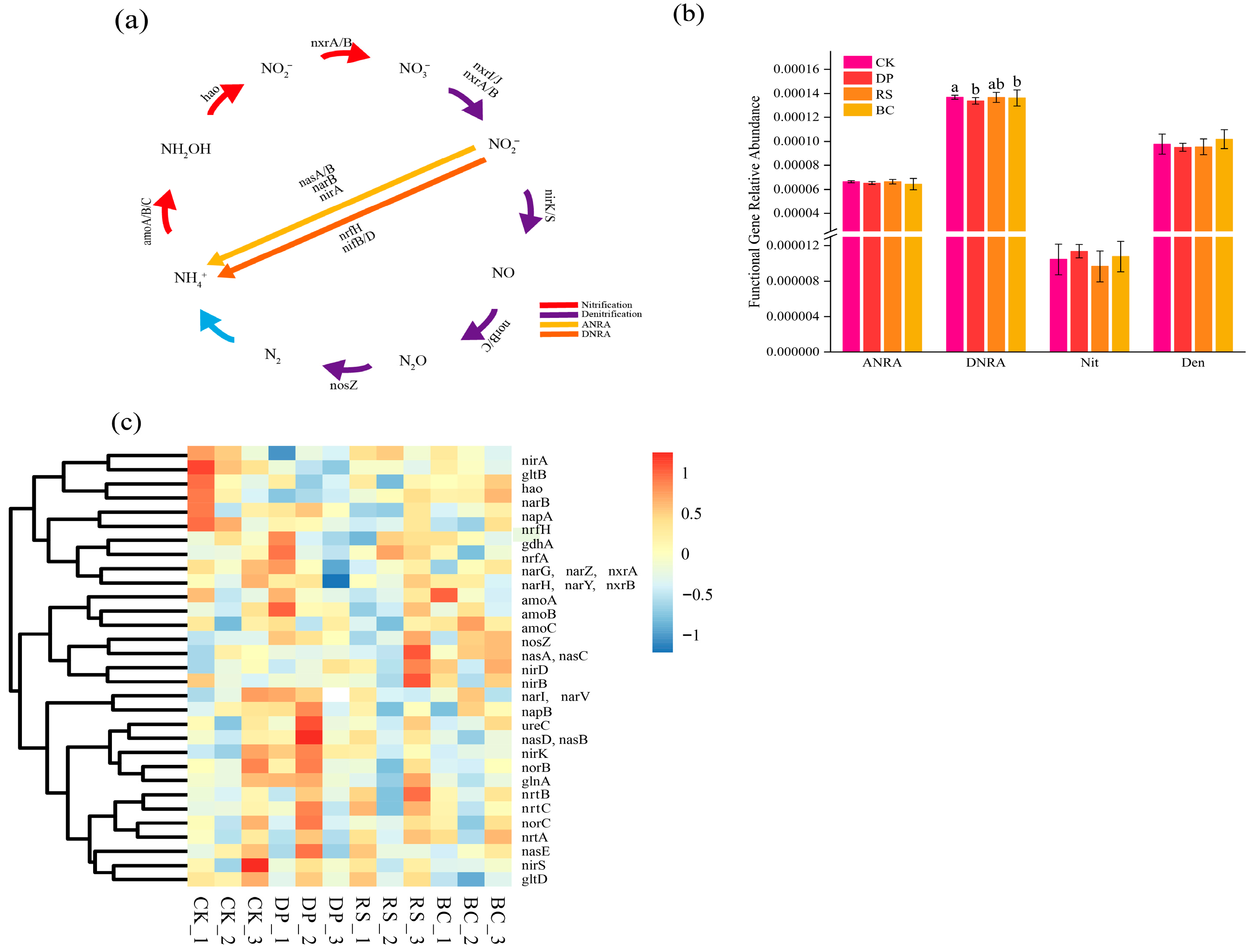

3.4. Effects of Organic Amendments on the Abundance of Nitrogen-Cycling Functional Genes

3.5. Association Between Microbial Community, Function, and Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Statistically Significant Differences in Soil Physical and Chemical Properties and Crop Yield Under Organic Amendments Treatments

4.2. Organic Substrate-Mediated Differentiation in Microbial Community Abundance

4.3. Physicochemical Improvement-Driven Pathway for Organic Amendments Yield Increase: Concurrent with Reduced Microbial Diversity and Formation of Specific Dominant Bacterial Populations

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, R.; Deng, H.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Deng, O. Plot-Scale Runoff Generation and Sediment Loss on Different Forest and Other Land Floors at a Karst Yellow Soil Region in Southwest China. Sustainability 2022, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Peng, B.; Xie, X.; Guo, C.; Ye, H. Analysis of spatiotemporal changes and driving forces of cultivated land in China from 1996 to 2019. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 983289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Han, W.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, G. Estimating and Mapping the Dynamics of Soil Salinity under Different Crop Types Using Sentinel-2 Satellite Imagery. Geoderma 2023, 440, 116738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yuan, M.; Chapman, S.J.; Zheng, N.; Yao, H.; Kuzyakov, Y. Bio-Converted Organic Wastes Shape Microbiota in Maize Rhizosphere: Localization and Identification in Enzyme Hotspots. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 184, 109105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Xiao, B.; Adnan, M. Effects of Ca2+ on Migration of Dissolved Organic Matter in Limestone Soils of the Southwest China Karst Area. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 5069–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, Q.; de Vries, W.; Ros, G.H.; Chen, X.; Muneer, M.A.; Zhang, F.; Wu, L. Effects of Soil Amendments on Soil Acidity and Crop Yields in Acidic Soils: A World-Wide Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Qi, Y.; Yin, C.; Liu, X. Effects of Nitrogen Reduction at Different Growth Stages on Maize Water and Nitrogen Utilization under Shallow Buried Drip Fertigated Irrigation. Agronomy 2024, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.; Nunes, M.R.; Kane, D.A.; Lin, Y. Soil health explains the yield-stabilizing effects of soil organic matter under drought. Soil Environ. Health 2023, 1, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, B.; Wu, Y.; Wu, L.; Bai, Y.; Chen, D. Soil Biota Associated with Soil N Cycling under Multiple Anthropogenic Stressors in Grasslands. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 193, 105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, M.T.; Raza, A.; Ali, S.; Bashir, S.; Kanwal, F.; Khan, I.; Raza, M.A.; Hussain, S.; Shen, F. Integrating By-Products from Bioenergy Technology to Improve the Morpho-Physiological Growth and Yield of Soybean under Acidic Soil. Chemosphere 2023, 327, 138424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Khan, A.L.; Al-Harrasi, A. Sphingomonas: From Diversity and Genomics to Functional Role in Environmental Remediation and Plant Growth. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Li, L.; Han, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Ruan, Z. Structural and Functional Analysis of the Bacterial Community in the Soil of Continuously Cultivated Lonicera Japonica Thunb. and Screening Antagonistic Bacteria for Plant Pathogens. Agronomy 2024, 14, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Chen, P.; Du, Q.; Yang, H.; Luo, K.; Wang, X.; Yang, F.; Yong, T.; Yang, W. Soil Organic Matter, Aggregates, and Microbial Characteristics of Intercropping Soybean under Straw Incorporation and N Input. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Niu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wei, W. 44-Years of Fertilization Altered Soil Microbial Community Structure by Changing Soil Physical, Chemical Properties and Enzyme Activity. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 3150–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis 2000, 3rd ed.; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.K. Soil Agricultural Chemistry Analysis Methods; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Islabão, G.O.; Vahl, L.C.; Timm, L.C.; Paul, D.L.; Kath, A.H. Rice Husk Ash as Corrective of Soil Acidity. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2014, 38, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malathi, P.; Preetha, K.; Selvi, D.; Parameswari, E.; Thamaraiselvi, S.P.; Sellamuthu, K.M. Eco-Friendly Utilization of Rice Husk Ash for Amending Acid Soils. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, E.M.; Kour, B.; Ramya, S.; Krishna, P.D.; Nazla, K.A.; Sudheer, K.; Anith, K.N.; Jisha, M.S.; Ramakrishnan, B. Rice in Acid Sulphate Soils: Role of Microbial Interactions in Crop and Soil Health Management. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 196, 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhao, F. Response Patterns of Soil Nitrogen Cycling to Crop Residue Addition: A Review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 1761–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dongchu, L.; Jing, H.; Ahmed, W.; Abbas, M.; Qaswar, M.; Anthonio, C.K.; Lu, Z.; Boren, W.; Yongmei, X.; et al. Soil Microbial Biomass and Extracellular Enzymes Regulate Nitrogen Mineralization in a Wheat-Maize Cropping System after Three Decades of Fertilization in a Chinese Ferrosol. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 21, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-L.; Lee, C.-H.; Jien, S.-H. Reduction of Nutrient Leaching Potential in Coarse-Textured Soil by Using Biochar. Water 2020, 12, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benghzial, K.; Raki, H.; Bamansour, S.; Elhamdi, M.; Aalaila, Y.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D.H. GHG Global Emission Prediction of Synthetic N Fertilizers Using Expectile Regression Techniques. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan-quan, C. Effcets of Slow-Released Nitrogen Fertilizer on Nitrogen Absorption, Distribution and Soil Nitrate, Ammonium Nitrogen Content of Plastic Film Mulching Contions. Guangdong Nong Ye Ke Xue 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, X.; Wu, C.; Cai, F.; Xu, Y. Effects of Delayed Nitrogen Fertilizer Drip Timing on Soil Total Salt, Cotton Yield and Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Efficiency. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 312, 109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Chen, H.; Tang, B.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G. Biochar Integrate Dicyandiamide Modified Soil Aggregates and Optimized Nitrogen Supplying to Boosting the Soybean-Wheat Yield in Saline-Alkali Soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2026, 257, 106922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yang, C.; Sainju, U.M.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, F.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Differential Responses of Soil Microbial N-Cycling Functional Genes to 35 Yr Applications of Chemical Fertilizer and Organic Manure in Wheat Field Soil on Loess Plateau. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.; Hou, R.; Dong, S.; Xue, P.; Yang, X.; Gao, Y. A Strategy for Reducing Nitrogen Fertilizer Application Based on Application of Biochar: A Case in Northeast China Black Soil Region (Mollisols). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 4997–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Xin, X.; Zheng, J.; Zong, T.; Dou, C. Effects of Biochar on Gaseous Carbon and Nitrogen Emissions in Paddy Fields: A Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Qu, J. Combined Application of Organic Materials Improves Soil Properties and Promotes Soil Nitrogen Cycling. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 36, 5711–5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Si, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lu, X.; Chen, X.; Han, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zou, W. Drivers of soil quality and maize yield under long-term tillage and straw incorporation in Mollisols. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 246, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Yong, T.; Yang, W. A Global Synthesis Reveals Additive Density Design Drives Inter cropping Effects on Soil N-Cycling Variables. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 191, 109318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Shang, J.; Liu, K.; He, Y.; Shao, X. The Synergistic Effect of Biochar and Microorganisms Greatly Improves Vegetation and Microbial Structure of Degraded Alpine Grassland on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, L.C.; Schulz, K.; Rißmann, C.; Cerull, E.; Plakias, A.; Schlichting, I.; Prochnow, A.; Ruess, L.; Trost, B.; Theuerl, S. Nitrogen Fertilization and Irrigation Types Do Not Affect the Overall N2O Production Potential of a Sandy Soil, but the Microbial Community Structure and the Quantity of Functional Genes Related to the N Cycle. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 192, 105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, F.-C.; Jia, B.; Gang, S.; Li, Y.; Mou, X.M.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Li, X.G. Regulation of Soil Nitrogen Cycling by Shrubs in Grasslands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 191, 109327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, Q.; Song, Q.; Liang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Song, F. Effects of Different Nitrogen Fertilizer Application Rates on Soil Microbial Structure in Paddy Soil When Combined with Rice Straw Return. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- XU, J.-Y.; MAO, Y.-P. From Canonical Nitrite Oxidizing Bacteria to Complete Ammonia Oxidizer: Discovery and Advances. Microbiology 2019, 46, 879–890. [Google Scholar]

- Lücker, S.; Wagner, M.; Maixner, F.; Pelletier, E.; Koch, H.; Vacherie, B.; Rattei, T.; Damsté, J.S.S.; Spieck, E.; Le Paslier, D.; et al. A Nitrospira Metagenome Illuminates the Physiology and Evolution of Globally Important Nitrite-Oxidizing Bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13479–13484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, H.; Cao, K.; Ye, L. Impact of Reduced Chemical Fertilizer and Organic Amendments on Yield, Nitrogen Use Efficiency, and Soil Microbial Dynamics in Chinese Flowering Cabbage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.F.A.; Pan, Y.; Bloem, J.; Berge, H.t.; Kuramae, E.E. Organic Nitrogen Rearranges Both Structure and Activity of the Soil-Borne Microbial Seedbank. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putz, M.; Schleusner, P.; Rütting, T.; Hallin, S. Relative Abundance of Denitrifying and DNRA Bacteria and Their Activity Determine Nitrogen Retention or Loss in Agricultural Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 123, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; He, T.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, C.; Yang, L.; Yang, L. Review of the Mechanisms Involved in Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction to Ammonium and the Efficacies of These Mechanisms in the Environment. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 345, 123480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley, O.E.; Gios, E.; Close, M.; Weaver, L.; Daughney, C.; Handley, K.M. Nitrogen Cycling and Microbial Cooperation in the Terrestrial Subsurface. ISME J. 2022, 16, 2561–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Xia, K.; Zhao, H.; Deng, P.; Teng, Z.; Xu, X. Soil Organic Carbon, pH, and Ammonium Nitrogen Controlled Changes in Bacterial Community Structure and Functional Groups after Forest Conversion. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1331672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Pang, X.P.; Li, J.; Duan, Y.Y.; Guo, Z.G. Effect of Foraging Tunnels Created by Small Subterranean Mammals on Soil Microbial Biomass Carbon and Organic Carbon Storage in Alpine Grasslands. CATENA 2024, 241, 108046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Basir, A.; Shah, S.T.; Rehman, M.U.; Hassan, M.u.; Zheng, H.; Basit, A.; Székely, Á.; Jamal, A.; Radicetti, E.; et al. Sustainable Soil Management in Alkaline Soils: The Role of Biochar and Organic Nitrogen in Enhancing Soil Fertility. Land 2024, 13, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, S.S.; Dubey, S.K.; Kumar, D.; Toor, A.S.; Walia, S.S.; Randhawa, M.K.; Kaur, G.; Brar, S.K.; Khambalkar, P.A.; Shivey, Y.S. Enhanced Organic Carbon Triggers Transformations of Macronutrients, Micronutrients, and Secondary Plant Nutrients and Their Dynamics in the Soil under Different Cropping Systems-A Review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 5272–5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Yu, S. Impact of Biochar on Nitrogen-Cycling Functional Genes: A Comparative Study in Mollisol and Alkaline Soils. Life 2024, 14, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chen, H.; Lin, H.; Liu, P.; Song, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, M.; Gao, W.; Song, L. Severe Nitrogen Leaching and Marked Decline of Nitrogen Cycle-Related Genes during the Cultivation of Apple Orchard on Barren Mountain. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 367, 108998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, X.; Gao, J.; Guo, J.; Fan, X.; Xing, W.; Gao, W.; Lin, M.; Wang, R. Impacts of Organic Fertilizer Substitution on Soil Ecosystem Functions: Synergistic Effects of Nutrients, Enzyme Activities, and Microbial Communities. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Gao, W.; Huang, S.; Tang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Masiliūnas, D. Organic Amendment Increases Soil Respiration in a Greenhouse Vegetable Production System through Decreasing Soil Organic Carbon Recalcitrance and Increasing Carbon-Degrading Microbial Activity. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 2877–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, X.; Chen, B.; Xiong, S.; Zhou, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Mou, Y. Impacts of Different Types of Straw Returning on Soil Physicochemical Properties, Microbial Community Structure, and Pepper Quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1620502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghari, A.A.; Abro, Q.; Leghari, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumari, L.; Nindwani, B.A.; Gull, S. Soil Organic Matter and Soil Structure Changes with Tillage Practices and Straw Incorporation in a Saline-Sodic Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1681651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; Zhang, J.; Xu, D.; Wang, E.; Bi, J.; Asante-Badu, B.; Njyenawe, M.C.; Sun, M.; Xue, P.; Wang, S.; et al. Keystone Microbial Taxa Drive the Accelerated Decompositions of Cellulose and Lignin by Long-Term Resource Enrichments. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 842, 156814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, S.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Lv, W. Long-Term Effects of Straw Return and Straw-Derived Biochar Amendment on Bacterial Communities in Soil Aggregates. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.; Liu, B.; Wei, R.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, L. Dynamics, Biodegradability. and Microbial Community Shift of Water-Extractable Organic Matter in Rice–Wheat Cropping Soil under Different Fertilization Treatments. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingthaisong, W.; Blagodatsky, S.; Vityakon, P.; Cadisch, G. Mixing Plant Residues of Different Quality Reduces Priming Effect and Contributes to Soil Carbon Retention. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 188, 109242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; He, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Gong, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Sui, G.; Zheng, W. Straw and Biochar Application Alters the Structure of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities in Direct-Seeded Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Paddies. Agronomy 2024, 14, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, K.; Jiang, Y.; Li, D.; Xie, Z.; Sun, B.; Wang, X. Divergent Accumulation of Microbe- and Plant-Derived Carbon in Different Soil Organic Matter Fractions in Paddy Soils under Long-Term Organic Amendments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 366, 108934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wei, X.; Zhu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Kuzyakov, Y.; et al. Organic Fertilizers Incorporation Increased Microbial Necromass Accumulation More than Mineral Fertilization in Paddy Soil via Altering Microbial Traits. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 193, 105137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.T.; Rong, L.; Rene, E.R.; Ali, Z.; Iqbal, H.; Sahito, Z.A.; Chen, Z. Effects of Vermicompost Preparation and Application on Waste Recycling, NH3, and N2O Emissions: A Systematic Review on Vermicomposting. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 35, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Liang, Y.; Dou, Y.; Zhao, F.; Wang, J. Long-Term Fertilization Differentially Increased the CAZyme Encoding Genes Responsible for Soil Organic Matter Decomposition under Winter Wheat on the Loess Plateau of China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 198, 105354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organic Amendments | pH | EC (μS/cm) | TC (g/kg) | TN (g/kg) | TP (g/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice husk | 7.83 | 136.4 | 325.88 | 28.51 | 3.92 |

| Rapeseed cake | 7.33 | 412.0 | 412.19 | 57.14 | 10.27 |

| biochar | 8.07 | 92.7 | 635.42 | 21.45 | 0.22 |

| Treatment | Organic Amendments | Base Fertilizer | Seed Fertilizer | Trumpet Fertilizer | Total N | Total P2O5 | Total K2O | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice Husk | Rapeseed Cake | Biochar | Compound Fertilizer | Ca(H2PO4)2 | N 46% | |||||

| CK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 525 | 225 | 210 | 278 | 303.23 | 104.75 | 78.70 |

| DP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 525 | 225 | 125 | 222 | 238.37 | 104.75 | 78.70 |

| RS | 8010 | 2250 | 0 | 525 | 225 | 125 | 222 | 238.37 | 104.75 | 78.70 |

| BC | 8010 | 2250 | 2010 | 525 | 225 | 125 | 222 | 238.37 | 104.75 | 78.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Li, J.; Long, J.; Liao, H.; Zhan, K.; Chen, H.; Lei, F. Enhancing Ecological Functions in Chinese Yellow Earth: Metagenomic Evidence of Microbial and Nitrogen Cycle Reassembly by Organic Amendments. Genes 2026, 17, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010009

Wu H, Li J, Long J, Liao H, Zhan K, Chen H, Lei F. Enhancing Ecological Functions in Chinese Yellow Earth: Metagenomic Evidence of Microbial and Nitrogen Cycle Reassembly by Organic Amendments. Genes. 2026; 17(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Han, Juan Li, Jian Long, Hongkai Liao, Kaixiang Zhan, Hongjie Chen, and Fenai Lei. 2026. "Enhancing Ecological Functions in Chinese Yellow Earth: Metagenomic Evidence of Microbial and Nitrogen Cycle Reassembly by Organic Amendments" Genes 17, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010009

APA StyleWu, H., Li, J., Long, J., Liao, H., Zhan, K., Chen, H., & Lei, F. (2026). Enhancing Ecological Functions in Chinese Yellow Earth: Metagenomic Evidence of Microbial and Nitrogen Cycle Reassembly by Organic Amendments. Genes, 17(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010009