Nasal Retinal Degeneration Is a Feature of a Subset of CRX-Associated Retinopathies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

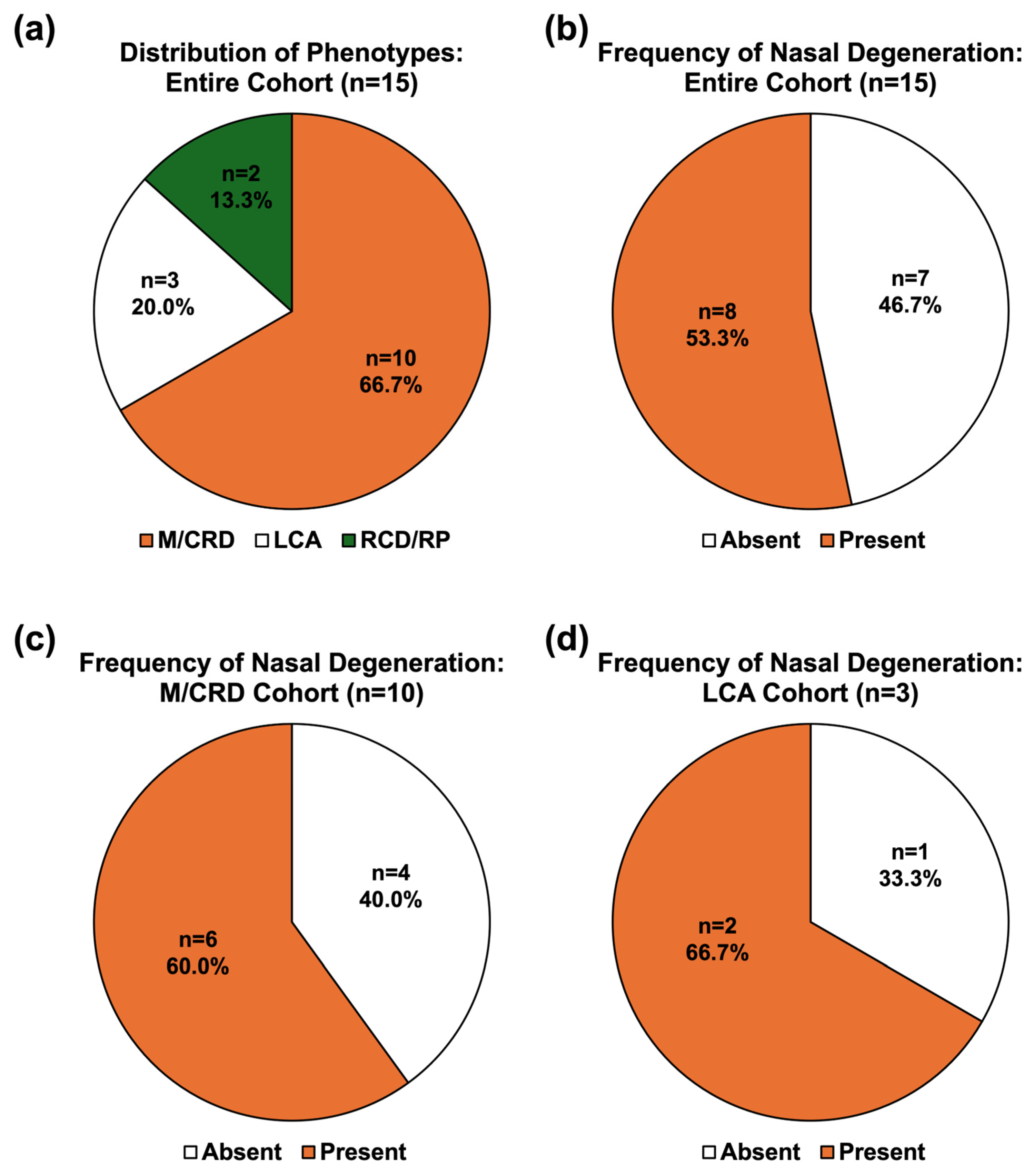

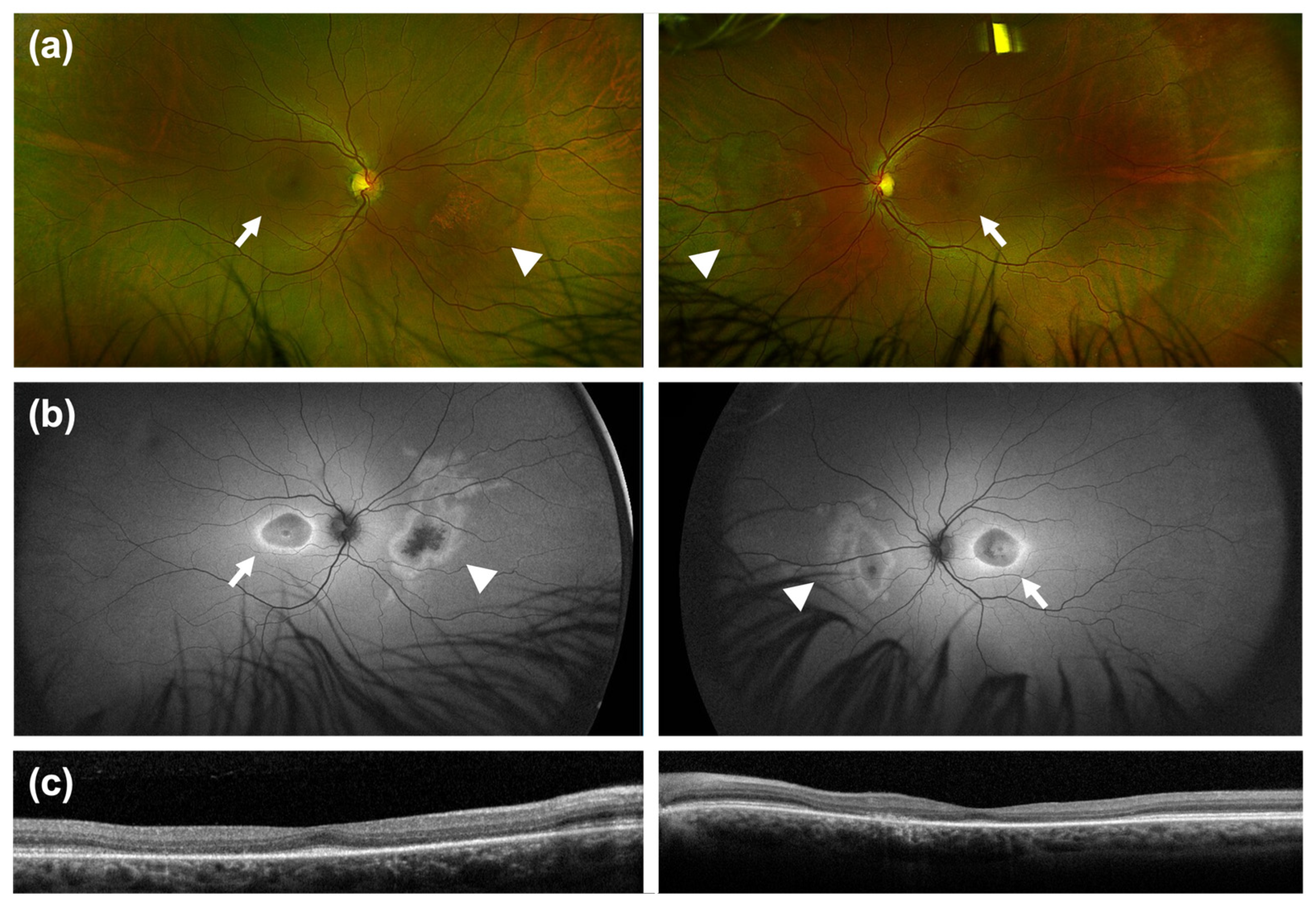

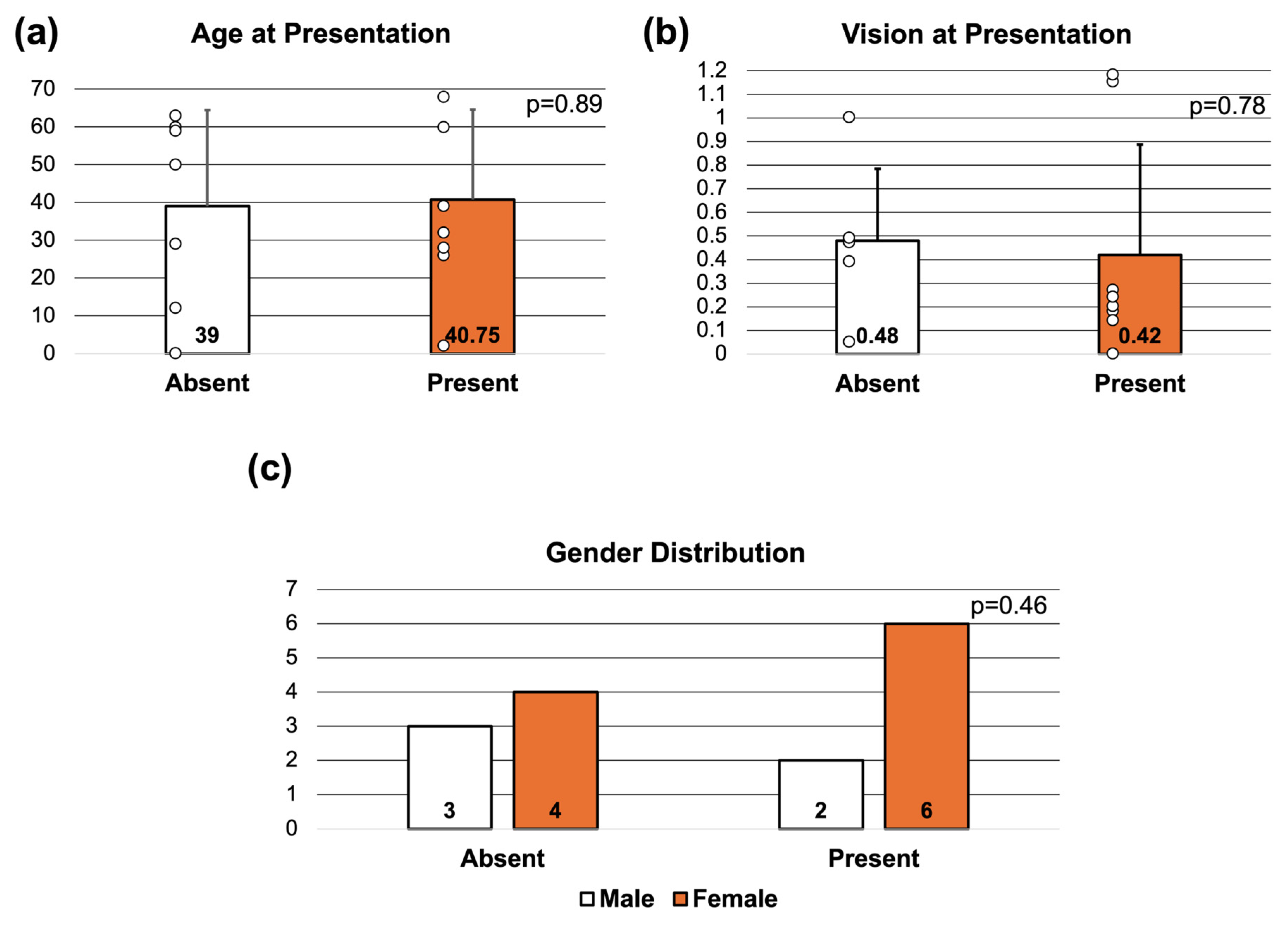

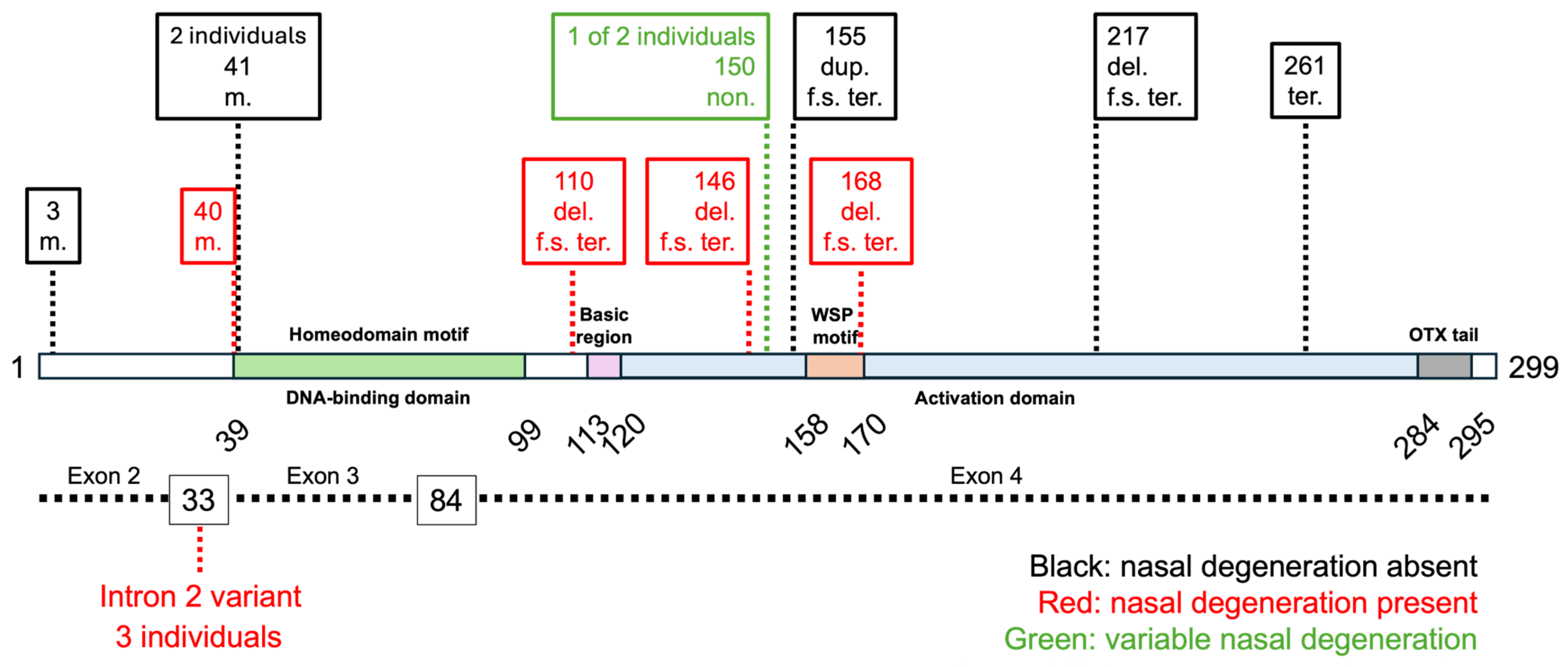

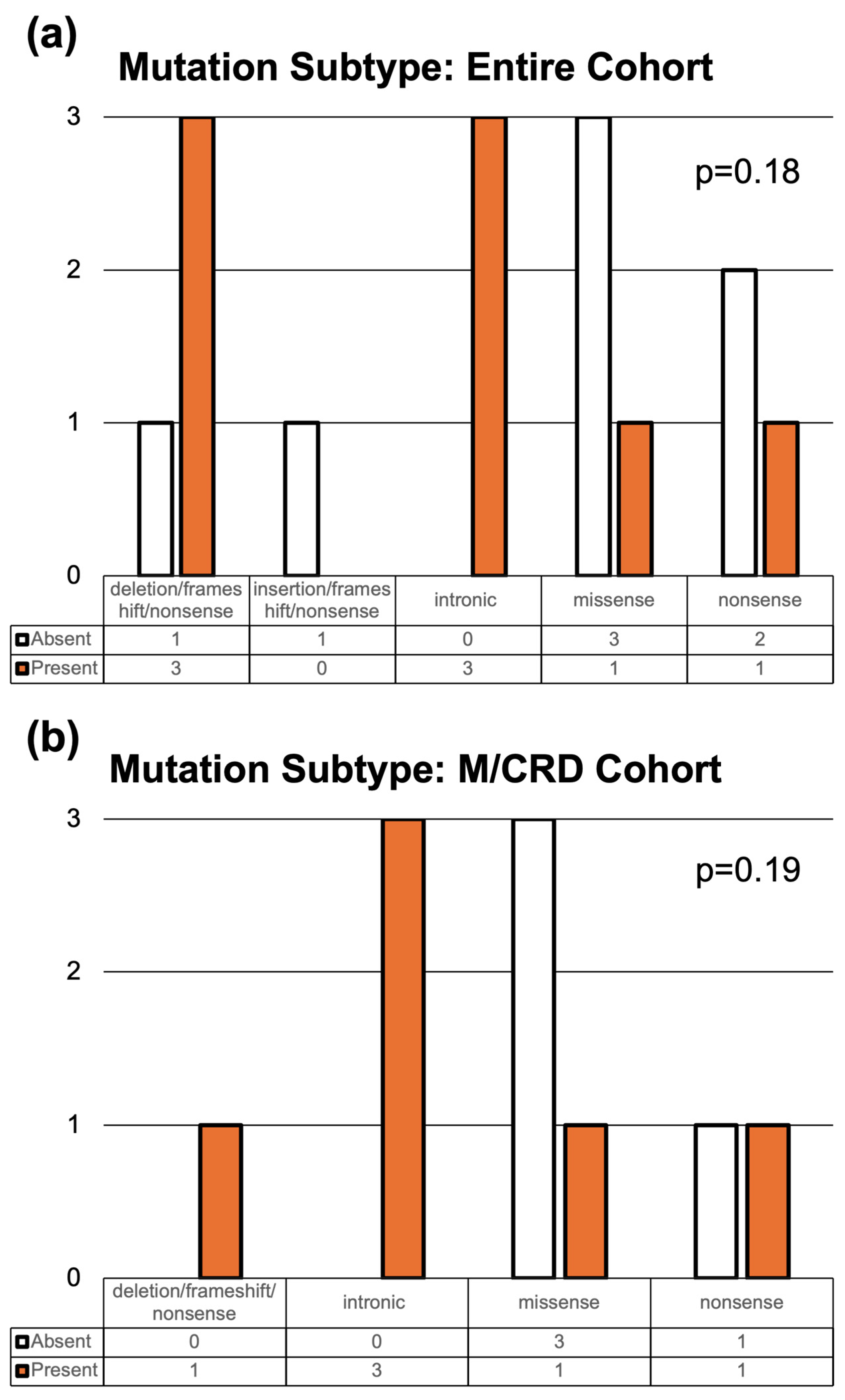

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRX | Cone-rod homeobox |

| IRD | Inherited retinal diseases |

| LCA | Leber congenital amaurosis |

| RCD | Rod-cone dystrophy |

| RP | Retinitis pigmentosa |

| M | Maculopathy |

| CRD | Cone-rod dystrophy |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| OTX | Orthodenticle-related homeobox |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| VUS | Variant of uncertain significance |

| SD-OCT | Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography |

| FAF | Fundus autofluorescence |

| ffERG | Full-field electroretinography |

| mfERG | Multifocal electroretinography |

| M/CRD | Maculopathy/cone-rod dystrophy |

| RCD/RP | Rod-cone dystrophy/retinitis pigmentosa |

References

- Evans, K.; Fryer, A.; Inglehearn, C.; Duvall-Young, J.; Whittaker, J.L.; Gregory, C.Y.; Butler, R.; Ebenezer, N.; Hunt, D.M.; Bhattacharya, S. Genetic Linkage of Cone-Rod Retinal Dystrophy to Chromosome 19q and Evidence for Segregation Distortion. Nat. Genet. 1994, 6, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, L.C.; van der Veen, I.; Georgiou, M.; van Schooneveld, M.J.; Ten Brink, J.B.; Florijn, R.J.; Mahroo, O.A.; de Carvalho, E.R.; Webster, A.R.; Bergen, A.A.; et al. Clinical, Genetic, and Histopathological Characteristics of CRX-Associated Retinal Dystrophies. Ophthalmol. Retina 2024, 9, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, G.-H.; Ahmad, O.; Ahmad, F.; Liu, J.; Chen, S. The Photoreceptor-Specific Nuclear Receptor Nr2e3 Interacts with Crx and Exerts Opposing Effects on the Transcription of Rod versus Cone Genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, S.; Arno, G.; Plagnol, V.; Chamney, S.; Russell-Eggitt, I.; Thompson, D.; Ramsden, S.C.; Black, G.C.M.; Robson, A.G.; Holder, G.E.; et al. The Phenotypic Variability of Retinal Dystrophies Associated with Mutations in CRX, with Report of a Novel Macular Dystrophy Phenotype. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 6934–6944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Chen, S. Gene Augmentation for Autosomal Dominant CRX-Associated Retinopathies. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1415, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolta, C.; Berson, E.L.; Dryja, T.P. Dominant Leber Congenital Amaurosis, Cone-Rod Degeneration, and Retinitis Pigmentosa Caused by Mutant Versions of the Transcription Factor CRX. Hum. Mutat. 2001, 18, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.G.; Joo, K.; Han, J.; Choi, M.; Kim, S.-W.; Park, K.H.; Park, S.J.; Lee, C.S.; Byeon, S.H.; Woo, S.J. Genotypic Profile and Clinical Characteristics of CRX-Associated Retinopathy in Koreans. Genes 2023, 14, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, L.L.; Alur, R.P.; Boobalan, E.; Sergeev, Y.V.; Caruso, R.C.; Stone, E.M.; Swaroop, A.; Johnson, M.A.; Brooks, B.P. Two Novel CRX Mutant Proteins Causing Autosomal Dominant Leber Congenital Amaurosis Interact Differently with NRL. Hum. Mutat. 2010, 31, E1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, S.; Smith, C.E.L.; Poulter, J.A.; McKibbin, M.; Arno, G.; Ellingford, J.; Kämpjärvi, K.; Khan, M.I.; Cremers, F.P.M.; Hardcastle, A.J.; et al. Late-Onset Autosomal Dominant Macular Degeneration Caused by Deletion of the CRX Gene. Ophthalmology 2023, 130, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Arno, G.; Robson, A.G.; Schiff, E.R.; Mohamed, M.D.; Michaelides, M.; Webster, A.R.; Mahroo, O.A. Bifocal Retinal Degeneration Observed on Ultra-Widefield Autofluorescence in Some Cases of CRX-Associated Retinopathy. Eye 2025, 39, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, F.-O.; Hamroun, D.; Lalande, M.; Collod-Béroud, G.; Claustres, M.; Béroud, C. Human Splicing Finder: An Online Bioinformatics Tool to Predict Splicing Signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujinami-Yokokawa, Y.; Yang, L.; Joo, K.; Tsunoda, K.; Liu, X.; Kondo, M.; Ahn, S.J.; Li, H.; Park, K.H.; Tachimori, H.; et al. Occult Macular Dysfunction Syndrome: Identification of Multiple Pathologies in a Clinical Spectrum of Macular Dysfunction with Normal Fundus in East Asian Patients: EAOMD Report No. 5. Genes 2023, 14, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.C.; Carrera, W.M.; McDonald, H.R.; Agarwal, A. Heterozygous CRX R90W Mutation-Associated Adult-Onset Macular Dystrophy with Phenotype Analogous to Benign Concentric Annular Macular Dystrophy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2020, 41, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.K.; Nuzbrokh, Y.; Lee, W.; de Carvalho, J.R.L.; Wong, N.K.; Sparrow, J.; Allikmets, R.; Tsang, S.H. A Mutation in CRX Causing Pigmented Paravenous Retinochoroidal Atrophy. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 32, NP235–NP239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, L.A.; Scanga, H.; Traboulsi, E.; Nischal, K.K. Novel Clinical Presentation of a CRX Rod-Cone Dystrophy. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e233711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.F.; DeBenedictis, M.J.; Traboulsi, E.I. A Novel Dominant CRX Mutation Causes Adult-Onset Macular Dystrophy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2018, 39, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Srikrupa, N.; Maitra, P.; Srilekha, S.; Porkodi, P.; Gnanasekaran, H.; Bhende, M.; Khetan, V.; Mathavan, S.; Bhende, P.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Genetic Testing and Phenotype Correlation in Retinitis Pigmentosa Patients from India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 2512–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.T.; Alarcon-Martinez, T.; Lopez, I.; Fajardo, N.; Chiang, J.; Koenekoop, R.K. A Complete, Homozygous CRX Deletion Causing Nullizygosity Is a New Genetic Mechanism for Leber Congenital Amaurosis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.M.; Petersen-Jones, S.M. Modifiers and Their Impact on Inherited Retinal Diseases: A Review. Ophthalmic Genet. 2025, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicinelli, M.V.; Manitto, M.P.; Parodi, M.B.; Bandello, F. Regressive Retinal Flecks in CRX-Mutated Early-Onset Retinal Dystrophy. Optom. Vis. Sci. Off. Publ. Am. Acad. Optom. 2016, 93, 1315–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piergentili, M.; Spagnuolo, V.; Murro, V.; Mucciolo, D.P.; Giorgio, D.; Passerini, I.; Pelo, E.; Giansanti, F.; Virgili, G.; Sodi, A. Atypic Retinitis Pigmentosa Clinical Features Associated with a Peculiar CRX Gene Mutation in Italian Patients. Med. Kaunas Lith. 2024, 60, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lines, M.A.; Hébert, M.; McTaggart, K.E.; Flynn, S.J.; Tennant, M.T.; MacDonald, I.M. Electrophysiologic and Phenotypic Features of an Autosomal Cone-Rod Dystrophy Caused by a Novel CRX Mutation. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 1862–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Tan, H.; Zeng, J.; Tao, D.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y. A Novel CRX Variant (p.R98X) Is Identified in a Chinese Family of Retinitis Pigmentosa with Atypical and Mild Manifestations. Genes Genom. 2019, 41, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Z.; Xiao, X.; Li, S.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Q. Pathogenicity Discrimination and Genetic Test Reference for CRX Variants Based on Genotype-Phenotype Analysis. Exp. Eye Res. 2019, 189, 107846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapi, M.; Sabbaghi, H.; Suri, F.; Alehabib, E.; Rahimi-Aliabadi, S.; Jamali, F.; Jamshidi, J.; Emamalizadeh, B.; Darvish, H.; Mirrahimi, M.; et al. Incomplete Penetrance of CRX Gene for Autosomal Dominant Form of Cone-Rod Dystrophy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2019, 40, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K.A.J.; Dhanji, S.R.; Kolawole, O.U.; Gregory-Evans, C.Y.; Gregory-Evans, K. Ethnic Disparities in Inherited Retinal Degenerations. Can. J. Ophthalmol. J. Can. Ophtalmol. 2025, 60, e869–e878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massengill, M.T.; Ash, N.F.; Young, B.M.; Ildefonso, C.J.; Lewin, A.S. Sectoral Activation of Glia in an Inducible Mouse Model of Autosomal Dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, M.; Grewal, P.S.; Narayan, A.; Alser, M.; Ali, N.; Fujinami, K.; Webster, A.R.; Michaelides, M. Sector Retinitis Pigmentosa: Extending the Molecular Genetics Basis and Elucidating the Natural History. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 221, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.S.; Martin, P.R.; Grünert, U. Topography of Neurons in the Rod Pathway of Human Retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 2848–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BCVA (Snellen, [logMAR]) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Gender | Age | OD | OS | Race | Ethnicity | Phenotype | Mutation | Mutation Subtype | Inheritance | Variant Classification |

| 1 | Female | 2 | 20/200, [1] | 20/400, [1.3] | White | Non-Hispanic or Latino | LCA | c.503_504del, p.Glu168Valfs*5 | Deletion/frameshift/nonsense | Heterozygous | Likely pathogenic |

| 2 | Female | 26 | 20/20, [0] | 20/70, [0.54] | White | Non-Hispanic or Latino | M/CRD | c.329delG, p.Gly110AlafsTer77 | Deletion/frameshift/nonsense | Heterozygous | Pathogenic |

| 3 | Male | 28 | 20/300, [1.2] | 20/300, [1.2] | White | Non-Hispanic or Latino | LCA | c.435delT, p.Leu146CysfsTer41 | Deletion/frameshift/nonsense | Heterozygous | Likely pathogenic |

| 4 | Male | 32 | 20/30, [0.2] | 20/40, [0.3] | White | Hispanic or Latino | M/CRD | c.449C>G, p.Serl50Ter | Nonsense | Heterozygous | Pathogenic |

| 5 | Female | 39 | 20/20, [0] | 20/20, [0] | White | Non-Hispanic or Latino | M/CRD | c.100+3G>C | Intronic | Heterozygous | VUS |

| 6 | Female | 60 | 20/25, [0.1] | 20/40, [0.3] | White | Non-Hispanic or Latino | M/CRD | c.100+3G>C | Intronic | Heterozygous | VUS |

| 7 | Female | 68 | 20/30, [0.2] | 20/25, [0.1] | White | Non-Hispanic or Latino | M/CRD | c.100+3_100+5delGAGinsTTA | Intronic | Heterozygous | Likely pathogenic |

| 8 | Female | 71 | 20/30, [0.2] | 20/30, [0.2] | White | Hispanic or Latino | M/CRD | c.118C>T, p.Arg40Trp | Missense | Heterozygous | Pathogenic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Massengill, M.T.; Juvier Riesgo, T.; Davis, J.L.; Mendoza-Santiesteban, C.E.; Goldhagen, B.E.; Lam, B.L.; Gregori, N.Z. Nasal Retinal Degeneration Is a Feature of a Subset of CRX-Associated Retinopathies. Genes 2026, 17, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010050

Massengill MT, Juvier Riesgo T, Davis JL, Mendoza-Santiesteban CE, Goldhagen BE, Lam BL, Gregori NZ. Nasal Retinal Degeneration Is a Feature of a Subset of CRX-Associated Retinopathies. Genes. 2026; 17(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleMassengill, Michael T., Tamara Juvier Riesgo, Janet L. Davis, Carlos E. Mendoza-Santiesteban, Brian E. Goldhagen, Byron L. Lam, and Ninel Z. Gregori. 2026. "Nasal Retinal Degeneration Is a Feature of a Subset of CRX-Associated Retinopathies" Genes 17, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010050

APA StyleMassengill, M. T., Juvier Riesgo, T., Davis, J. L., Mendoza-Santiesteban, C. E., Goldhagen, B. E., Lam, B. L., & Gregori, N. Z. (2026). Nasal Retinal Degeneration Is a Feature of a Subset of CRX-Associated Retinopathies. Genes, 17(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010050