Pilot Study of Preconception Carrier Screening in Russia: Initial Findings and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment

2.2. Panel Design

2.3. Testing

2.4. DNA Isolation

2.5. Analysis of CYP21A2 Common Variants

2.6. Analysis of CFTR 21kb Deletion

2.7. Analysis of SMN1 Exon 7 Deletion

2.8. Analysis of DMD Exonic Deletions and Duplications

2.9. Exome Libraries Preparation and Sequencing

2.10. Targeted Amplicon Sequencing

2.10.1. Bioinformatics Analysis of Clinical Exomes Data

2.10.2. Variant Interpretation

2.10.3. Statistics

3. Results

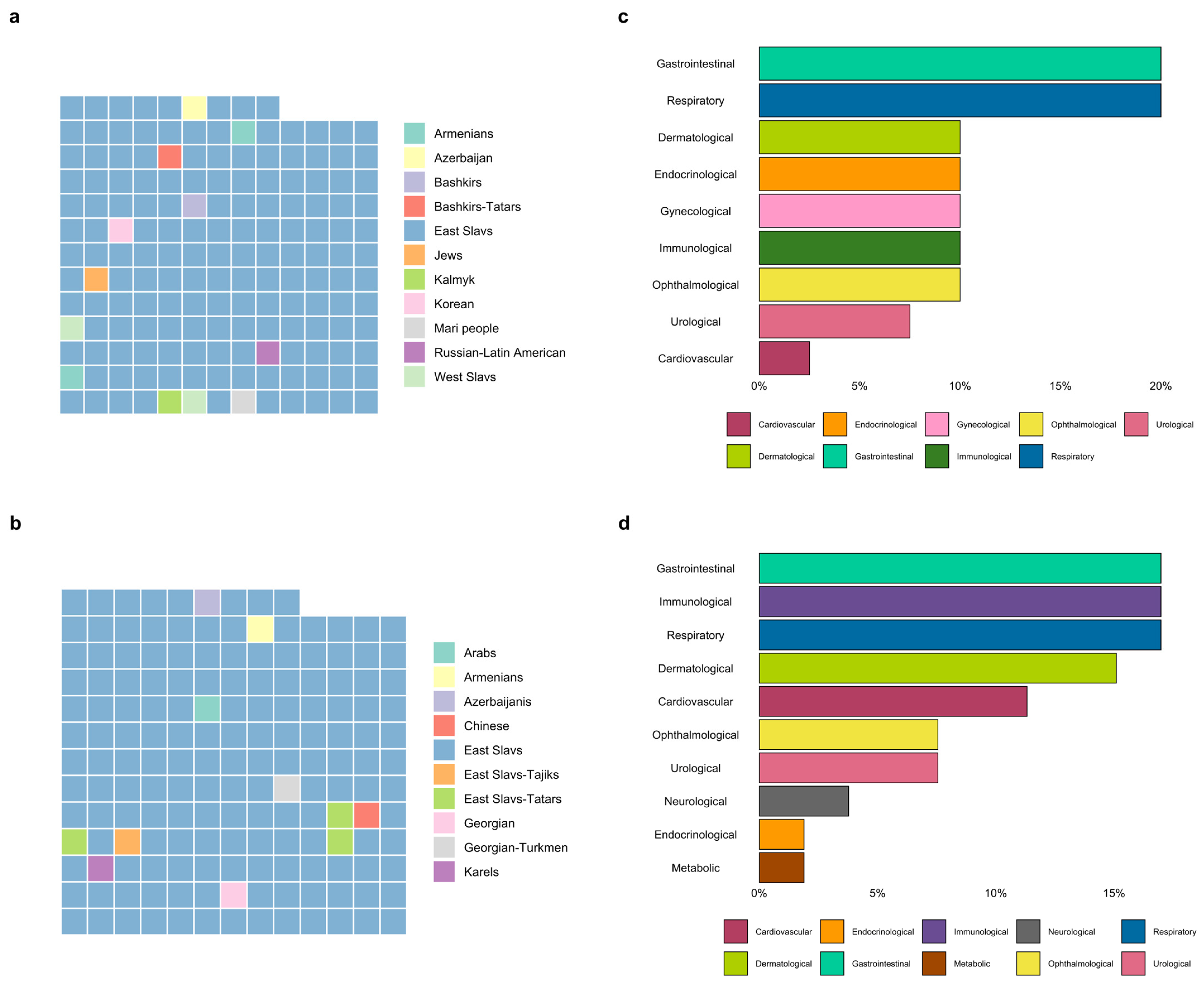

3.1. Description of the Group

3.2. Assessment of the Carrier Frequency

3.3. Couples at High Risk of AR or XL Disease

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| AR | Autosomal Recessive |

| ART | Assisted reproductive technologies |

| CS | Carrier screening |

| IVF | In Vitro Fertilization |

| P/LP | Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic variant |

| PD | Prenatal diagnosis |

| PGT-M | Preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disease |

References

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM®. 2025. Available online: https://www.omim.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- EURODIS. Available online: https://eurodis.com/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Rowe, C.A.; Wright, C.F. Expanded universal carrier screening and its implementation within a publicly funded healthcare service. J. Community Genet. 2020, 11, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grody, W.W.; Thompson, B.H.; Gregg, A.R.; Bean, L.H.; Monaghan, K.G.; Schneider, A.; Lebo, R.V. ACMG position statement on prenatal/preconception expanded carrier screening. Genet. Med. 2013, 15, 482–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aul, R.B.; Canales, K.E.; De Bie, I.; Laberge, A.-M.; Langlois, S.; Nelson, T.N.; Walji, S.; Yu, A.C.; Lazier, J. Reproductive carrier screening for genetic disorders: Position statement of the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists. J. Med. Genet. 2025, 62, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.; Sagi-Dain, L. Impact of a national genetic carrier-screening program for reproductive purposes. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregg, A.R.; Aarabi, M.; Klugman, S.; Leach, N.T.; Bashford, M.T.; Goldwaser, T.; Chen, E.; Sparks, T.N.; Reddi, H.V.; Rajkovic, A.; et al. Screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions during pregnancy and preconception: A practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1793–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, A.D.; McClaren, B.J.; Caruana, J.; Tutty, E.; King, E.A.; Halliday, J.L.; Best, S.; Kanga-Parabia, A.; Bennetts, B.H.; Cliffe, C.C.; et al. The Australian Reproductive Genetic Carrier Screening Project (Mackenzie’s Mission): Design and Implementation. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, S.; Zhang, V.W.; Cao, L.; Liu, H.; Wei, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, F.; et al. Customizing carrier screening in the Chinese population: Insights from a 334-gene panel. Prenat. Diagn. 2024, 44, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurmans, J.; Birnie, E.; Van Den Heuvel, L.M.; Plantinga, M.; Lucassen, A.; Van Der Kolk, D.M.; Abbott, K.M.; Ranchor, A.V.; Diemers, A.D.; Van Langen, I.M. Feasibility of couple-based expanded carrier screening offered by general practitioners. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 27, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gug, M.; Andreescu, N.; Caba, L.; Popoiu, T.-A.; Mozos, I.; Gug, C. The Landscape of Genetic Variation and Disease Risk in Romania: A Single-Center Study of Autosomal Recessive Carrier Frequencies and Molecular Variants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasovskiy, S.A.; Kashirskaya, N.Y.; Chernyak, A.V.; Amelina, E.L.; Petrova, N.V.; Polyakov, A.V.; Kondrat’eva, E.I.; Voronkova, A.Y.; Usacheva, M.V.; Adyan, T.A.; et al. Genetic characterization of cystic fibrosis patients in Russian Federation according to the National Register, 2014. Pulmonology 2016, 26, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barbitoff, Y.A.; Khmelkova, D.N.; Pomerantseva, E.A.; Slepchenkov, A.V.; Zubashenko, N.A.; Mironova, I.V.; Kaimonov, V.S.; Polev, D.E.; Tsay, V.V.; Glotov, A.S.; et al. Expanding the Russian allele frequency reference via cross-laboratory data integration: Insights from 7452 exome samples. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nykamp, K.; Anderson, M.; Powers, M.; Garcia, J.; Herrera, B.; Ho, Y.-Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Patil, N.; Thusberg, J.; Westbrook, M.; et al. Sherloc: A comprehensive refinement of the ACMG–AMP variant classification criteria. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryzhkova, O.P.; Kardymon, O.L.; Prokhorchuk, E.B.; Konovalov, F.A.; Maslennikov, A.B.; Stepanov, V.A.; Afanasyev, A.A.; Zaklyazminskaya, E.V.; Rebrikov, D.V.; Savostyanov, K.V.; et al. Guidelines for the Interpretation of Human DNA Sequence Data Obtained by Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS) Methods (2018 Edition, Version 2). Med. Genet. 2019, 18, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinovskaya, N.S.; Glavnova, O.B.; Yarmolinskaya, M.I.; Sultanov, I.Y.; Klyuchnikov, D.Y.; Tkachenko, N.N.; Nasykhova, Y.A.; Glotov, A.S. Analysis of the pathogenic CYP21A2 gene variants in patients with clinical, biochemical and combined manifestations of hyperandrogenism. J. Obstet. Women’s Dis. 2022, 71, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbitoff, Y.A.; Skitchenko, R.K.; Poleshchuk, O.I.; Shikov, A.E.; Serebryakova, E.A.; Nasykhova, Y.A.; Polev, D.E.; Shuvalova, A.R.; Shcherbakova, I.V.; Fedyakov, M.A.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing provides insights into monogenic disease prevalence in Northwest Russia. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2019, 7, e964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratyeva, E.I.; Voronkova, A.Y.; Kashirskaya, N.Y.; Krasovsky, S.A.; Starinova, M.A.; Amelina, E.L.; Avdeev, S.N.; Kutsev, S.I. Russian registry of patients with cystic fibrosis: Lessons and perspectives. Pulmonology 2023, 33, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glotov, A.S.; Chernykh, V.B.; Solovova, O.A.; Polyakov, A.V.; Donnikov, M.Y.; Kovalenko, L.V.; Barbitoff, Y.A.; Nasykhova, Y.A.; Lazareva, T.E.; Glotov, O.S. Russian Regional Differences in Allele Frequencies of CFTR Gene Variants: Genetic Monitoring of Infertile Couples. Genes 2023, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselev, A.; Maretina, M.; Shtykalova, S.; Al-Hilal, H.; Maslyanyuk, N.; Plokhih, M.; Serebryakova, E.; Frolova, M.; Shved, N.; Krylova, N.; et al. Establishment of a Pilot Newborn Screening Program for Spinal Muscular Atrophy in Saint Petersburg. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, T.M.; Blitzer, M.G.; Wolf, B. Technical standards and guidelines for the diagnosis of biotinidase deficiency. Genet. Med. 2010, 12, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 762: Prepregnancy Counseling. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, e78–e89. [CrossRef]

- Arkhangelskiy, V.N.; Zolotareva, O.A.; Kuchmaeva, O.V. Age-Based Fertility Model for Calendar Years and Real Generations: Method for Constructing and Analytical Possibilities. Vopr. stat. 2024, 31, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Jin, S.; Huang, L.; Shao, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Su, M.; Tan, J.; Cheng, Q.; et al. A capillary electrophoresis-based assay for carrier screening of the hotspot mutations in the CYP21A2 gene. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanlikit, Y.; Panthan, B.; Chitayanan, P.; Klumsathian, S.; Charoenyingwattana, A.; Chantratita, W.; Trachoo, O. Nationwide carrier screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia: Integrated approach of CYP21A2 pathogenic variant genotyping and comprehensive large gene deletion analysis. BMC Med. Genom. 2025, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, L.; Paul, S.; ReKha, A.; Asha, H.; Mathai, S.; Simon, A.; Danda, S.; Thomas, N.; Chapla, A. P227: High carrier frequency of CYP21A2 hotspot mutations in Southern India: Underscoring the need for genetic testing in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Genet. Med. Open 2024, 2, 101124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neocleous, V.; Shammas, C.; Phedonos, A.; Phylactou, L.; Skordis, N. Phenotypic variability of hyperandrogenemia in females heterozygous for CYP21A2 mutations. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, L.; Archibald, A.D.; Dive, L.; Delatycki, M.B.; Kirk, E.P.; Laing, N.; Newson, A.J. Considering severity in the design of reproductive genetic carrier screening programs: Screening for severe conditions. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 33, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Wen, J.; Zhang, H.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, H.; Liang, D.; Wu, L.; Li, Z. Comprehensive analysis of NGS-based expanded carrier screening and follow-up in southern and southwestern China: Results from 3024 Chinese individuals. Hum. Genom. 2024, 18, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinakis, N.M.; Tilemis, F.-N.; Veltra, D.; Svingou, M.; Sofocleous, C.; Kekou, K.; Kosma, K.; Kampouraki, A.; Kontse, C.; Fylaktou, I.; et al. Estimating at-risk couple rates across 1000 exome sequencing data cohort for 176 genes and its importance relevance for health policies. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 33, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, D.; Peng, J.; Chen, G.; Dong, X. Diagnostic yield of expanded carrier screening of a multi-ethnic population in Yunnan, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, E.P.; Delatycki, M.B.; Archibald, A.D.; Tutty, E.; Caruana, J.; Halliday, J.L.; Lewis, S.; McClaren, B.J.; Newson, A.J.; Dive, L.; et al. Nationwide, Couple-Based Genetic Carrier Screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1877–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, I.S.; Lazarin, G.A.; Kang, H.P.; Evans, E.A.; Goldberg, J.D.; Wapner, R.J. Modeled Fetal Risk of Genetic Diseases Identified by Expanded Carrier Screening. JAMA 2016, 316, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grody, W.W.; Cutting, G.R.; Klinger, K.W.; Richards, C.S.; Watson, M.S.; Desnick, R.J. Laboratory standards and guidelines for population-based cystic fibrosis carrier screening. Genet. Med. 2001, 3, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To-Mai, X.-H.; Nguyen, H.-T.; Nguyen-Thi, T.-T.; Nguyen, T.-V.; Nguyen-Thi, M.-N.; Thai, K.-Q.; Lai, M.-T.; Nguyen, T.-A. Prevalence of common autosomal recessive mutation carriers in women in the Southern Vietnam following the application of expanded carrier screening. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, M.J.; Bashar, A.; Soman, V.; Nkrumah, E.A.F.; Al Mulla, H.; Darabi, H.; Wang, J.; Kiehl, P.; Sethi, R.; Dungan, J.; et al. Leveraging diverse genomic data to guide equitable carrier screening: Insights from gnomAD v.4.1.0. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 112, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetruengchai, W.; Phowthongkum, P.; Shotelersuk, V. Carrier frequency estimation of pathogenic variants of autosomal recessive and X-linked recessive mendelian disorders using exome sequencing data in 1642 Thais. BMC Med. Genom. 2024, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, T.S.; Schneider, E.; Boniferro, E.; Brockhoff, E.; Johnson, A.; Stoffels, G.; Feldman, K.; Grubman, O.; Cole, D.; Hussain, F.; et al. Barriers to completion of expanded carrier screening in an inner city population. Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.; Zhou, N.; He, Q.; Lin, N.; He, S.; He, D.; Dai, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, H.; et al. Regional patterns of genetic variants in expanded carrier screening: A next-generation sequencing pilot study in Fujian Province, China. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1527228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksiutenko, E.M.; Bezdvornykh, I.V.; Barbitoff, Y.A.; Nasykhova, Y.A.; Glotov, A.S. PLoV: A comprehensive database of genetic variants leading to pregnancy loss. Database 2025, 2025, baaf037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinovskaya, N.S.; Abashova, E.I.; Yarmolinskaya, M.I.; Bredgauer, M.D.; Sultanov, I.Y.; Nasykhova, Y.A.; Glotov, A.S. Characteristics of polymorphism of genes involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism and steroid hormone synthesis in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Obstet. Women’s Dis. 2025, 73, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubina, J.; Tolmacheva, E.; Maslennikov, D.; Kochetkova, T.; Mukosey, I.; Sadelov, I.; Goltsov, A.; Barkov, I.; Ekimov, A.; Rogacheva, M.; et al. WES-based screening of 7,000 newborns: A pilot study in Russia. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2024, 5, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Gene | Variant |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CFTR | rs113993960 (c.1521_1523del) |

| GJB2 | rs80338939 (c.35del) | |

| 13 | SMN1 | del7 |

| DHCR7 | rs11555217 (c.452G>A) | |

| 18 | CFTR | rs113993960 (c.1521_1523del) |

| SLC26A2 | c.310del | |

| 21 | CYP21A2 | rs7755898 (c.955C>T) |

| CFTR | rs75961395 (c.254G>A) | |

| 65 | GJB2 | rs80338939 (c.35del) |

| SERPINA1 | rs28929474 (c.1096G>A) | |

| 80 | ATP7B | rs76151636 (c.3207C>A) |

| CYP21A2 | rs7755898 (c.955C>T) | |

| 83 | PAH | rs5030858 (c.1222C>T) |

| SERPINA1 | rs28931570 (c.187C>T) | |

| 90 | DHCR7 | rs11555217 (c.452G>A) |

| GJB2 | rs80338939 (c.35del) | |

| 123 | CYP21A2 | rs7755898 (c.955C>T) |

| DHCR7 | rs749076525 (c.651C>A) | |

| 158 | SMN1 | del7 |

| SERPINA1 | rs17580 | |

| 11 | DMD | dup 38-39 ex c.(5325+1_5326-1)_(5586+1_5587-1)dup |

| ABCA4 | rs1800552 (c.5693G>A) | |

| DHCR7 | rs11555217 (c.452G>A) | |

| 85 | ATP7B | rs191312027 (c.2605G>T) |

| CFTR | rs115545701 (c.220C>T) | |

| SMN1 | del7 | |

| 102 | ACADM | rs147559466 (c.127G>A) |

| ATP7B | rs76151636 (c.3207C>A) | |

| CYP21A2 | rs12530380/rs7755898 (c.710T>A/c.955C>T) | |

| 140 | ABCA4 | rs61749420 (c.1957C>T) |

| CYP21A2 | rs6471 (c.844G>T) | |

| PAH | rs5030858 (c.1222C>T) |

| Gene | Phenotype (MIM Number) | Number of Cases Identified | Carrier Frequency (1 in N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP21A2 | Adrenal Hyperplasia, Congenital, Due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency (201910) Hyperandrogenism, nonclassic type, due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency included | 13 | 1 in 13 |

| GJB2 | Sensorineural nonsyn-dromic hearing loss (604418) | 9 | 1 in 18 |

| SERPINA1 | Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency (613490) | 9 | 1 in 18 |

| ATP7B | Wilson Disease (277900) | 6 | 1 in 28 |

| CFTR | Cystic fibrosis (219700); Congenital bilateral absence of vas deferens (277180) | 5 | 1 in 33 |

| ABCA4 | Stargardt Disease 1 (248200); Cone-rod dystrophy 3 (604116); Retinitis pigmentosa 19 (601718) | 5 | 1 in 33 |

| SMN1 | Spinal Muscular Atrophy-1, 2, 3, 4 (253300, 253550, 253400, 271150) | 5 | 1 in 33 |

| DHCR7 | Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome (270400) | 4 | 1 in 41 |

| GALT | Galactosemia (230400) | 3 | 1 in 55 |

| PKHD1 | Polycystic kidney disease 4, with or without hepatic disease (263200) | 3 | 1 in 55 |

| SLC26A4 | Deafness, autosomal recessive 4, with enlarged vestibular aqueduct (600791); Pendred syndrome (274600) | 2 | 1 in 83 |

| PAH | Phenylketonuria (261600) | 2 | 1 in 83 |

| IDUA | Mucopolysaccharidosis Ih (607014); Mucopolysaccharidosis Ih/s (607015); Mucopolysaccharidosis Is (607016) | 2 | 1 in 83 |

| DMD | Becker muscular dystrophy (300376); Duchenne muscular dystrophy (310200) | 1 | 1 in 165 |

| ALPL | Hypophosphatasia (146300, 241510, 241500) | 1 | 1 in 165 |

| USH2A | Retinitis pigmentosa 39 (613809); Usher syndrome, type 2A (276901) | 1 | 1 in 165 |

| ACADS | Acyl-Coa Dehydrogenase, Short-Chain, Deficiency of (201470) | 1 | 1 in 165 |

| ACADM | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium chain, deficiency of (201450) | 1 | 1 in 165 |

| BTD | Biotinidase deficiency (253260) | 1 | 1 in 165 |

| PLOD1 | Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, kyphoscoliotic type, 1 (225400) | 1 | 1 in 165 |

| SLC26A2 | Achondrogenesis Ib (600972); Atelosteogenesis, type II (256050); Diastrophic dysplasia (222600); Epiphyseal dysplasia, multiple, 4 (226900) | 1 | 1 in 165 |

| Gene | Nucleotide Change | Protein Change | dbSNP | Cohort AF | gnomAD_ allele Frequency v4.1.0 | Northwest Russia, AF | Ruseq AF (Healthy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP21A2 | c.844G>T | p.Val282Leu | rs6471 | 0.0303 | 0.005 | - | - |

| CYP21A2 | c.955C>T | p.Gln319Ter | rs7755898 | 0.0303 | 0.0008961 | 0.00000 | - |

| GJB2 | c.35del | p.Gly12fs | rs80338939 | 0.0303 | 0.00705 | 0.01837 | 0.01521 |

| SMN1 | deletion of the 7 ex | 0.0303 | - | - | - | ||

| SERPINA1 | c.863A>T | p.Glu288Val | rs17580 | 0.02424 | 0.03636 | 0.00669 | 0.007113 |

| SERPINA1 | c.1096G>A | p.Glu366Lys | rs28929474 | 0.01818 | 0.01586 | - | - |

| ABCA4 | c.5882G>A | p.Gly1961Glu | rs1800553 | 0.01818 | 0.003406 | 0.00746 | 0.009775 |

| DHCR7 | c.452G>A | p.Trp151Ter | rs11555217 | 0.01818 | 0.0007107 | 0.00658 | 0.005045 |

| ATP7B | c.3207C>A | p.His1069Gln | rs76151636 | 0.01212 | 0.0009435 | 0.00618 | 0.005651 |

| CFTR | c.1521_1523del | p.Phe508del | rs113993960 | 0.00606 | 0.01193 | 0.00623 | 0.008021 |

| Family ID | Gene | Female Partner P/LP Variant | Male Partner P/LP Variant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | ATP7B | c.3688A>G (p.Ile1230Val, rs200911496) | c.3207C>A (p.His1069Gln, rs76151636) |

| 66 | CFTR | c.1397C>G (p.Ser466Ter, rs121908805) | c.1521_1523del (p.Phe508del, rs113993960) |

| 90 | DHCR7 | c.452G>A (p.Trp151Ter, rs11555217) | c.964-1G>T (rs138659167) |

| 41 | GJB2 | c.35del (p.Gly12fs, rs80338939) | c.101T>C (p.Met34Thr, rs35887622) |

| 65 | GJB2 | c.35del (p.Gly12fs, rs80338939) | c.109G>A (p.Val37Ile, rs72474224) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Glotov, A.S.; Nasykhova, Y.A.; Lazareva, T.E.; Dvoynova, N.M.; Shabanova, E.S.; Danilova, M.M.; Osinovskaya, N.S.; Barbitoff, Y.A.; Maretina, M.A.; Gorodnicheva, E.E.; et al. Pilot Study of Preconception Carrier Screening in Russia: Initial Findings and Challenges. Genes 2026, 17, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010003

Glotov AS, Nasykhova YA, Lazareva TE, Dvoynova NM, Shabanova ES, Danilova MM, Osinovskaya NS, Barbitoff YA, Maretina MA, Gorodnicheva EE, et al. Pilot Study of Preconception Carrier Screening in Russia: Initial Findings and Challenges. Genes. 2026; 17(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlotov, Andrei S., Yulia A. Nasykhova, Tatyana E. Lazareva, Natalya M. Dvoynova, Elena S. Shabanova, Maria M. Danilova, Natalia S. Osinovskaya, Yury A. Barbitoff, Marianna A. Maretina, Elizaveta E. Gorodnicheva, and et al. 2026. "Pilot Study of Preconception Carrier Screening in Russia: Initial Findings and Challenges" Genes 17, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010003

APA StyleGlotov, A. S., Nasykhova, Y. A., Lazareva, T. E., Dvoynova, N. M., Shabanova, E. S., Danilova, M. M., Osinovskaya, N. S., Barbitoff, Y. A., Maretina, M. A., Gorodnicheva, E. E., Tonyan, Z. N., Kiselev, A. V., Basipova, A. A., Bespalova, O. N., & Kogan, I. Y. (2026). Pilot Study of Preconception Carrier Screening in Russia: Initial Findings and Challenges. Genes, 17(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010003