Identification and Validation of Tissue-Specific Housekeeping Markers for the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Total RNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatics Analyses and Identification of Housekeeping Genes (HKGs)

2.4. Multiple Alignments and Cladograms

2.5. Validation of Candidate Housekeeping Gene (HKG) Markers

2.6. Marker Specificity and Amplification Efficiency

2.7. Methods for Analyzing HKG Stability

3. Results

3.1. Gene Identification and Characterization

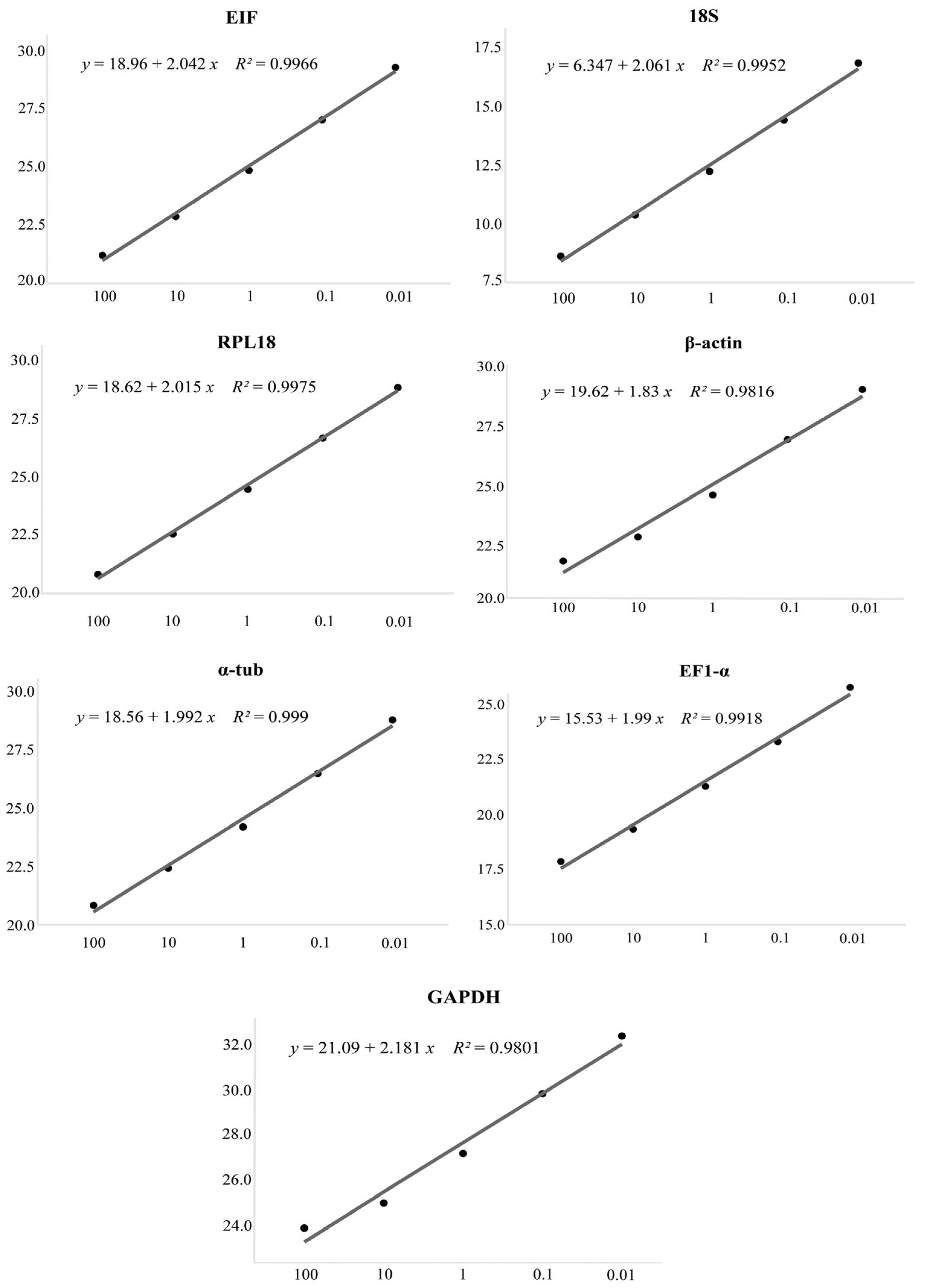

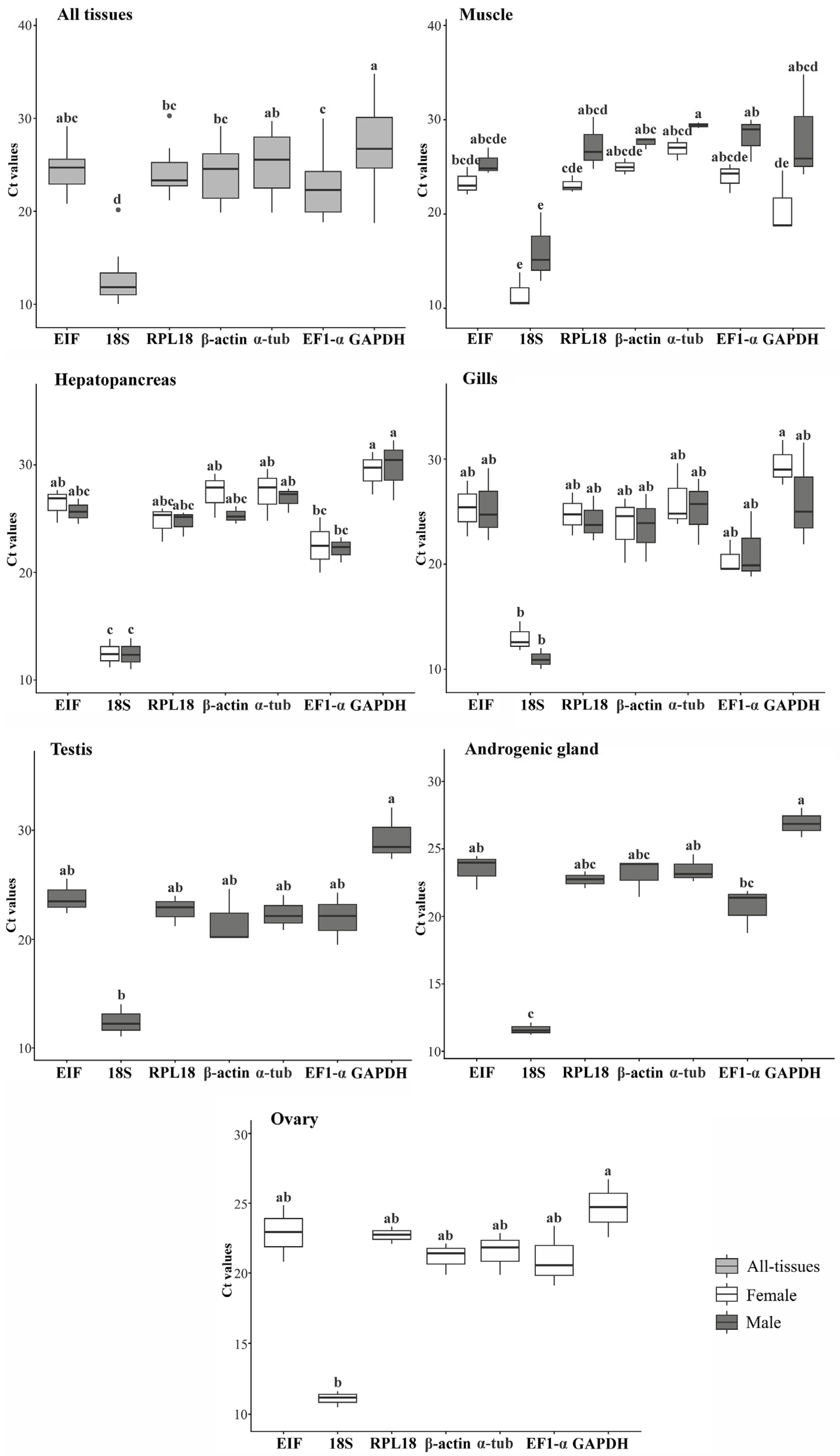

3.2. Specificity and Efficiency of Housekeeping Markers

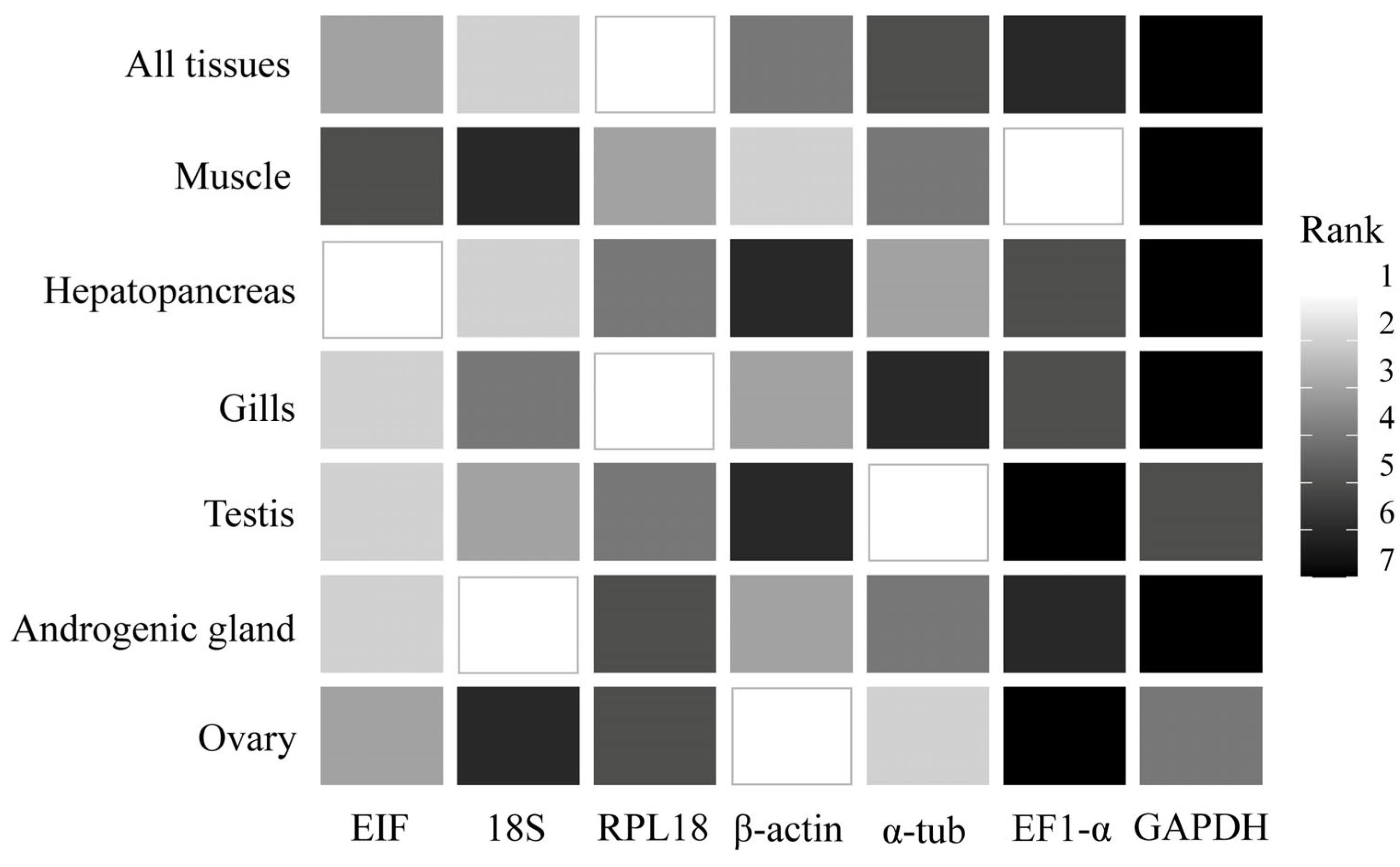

3.3. Stability of Candidate HKGs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kubista, M.; Andrade, J.M.; Bengtsson, M.; Forootan, A.; Jonák, J.; Lind, K.; Sindelka, R.; Sjöback, R.; Sjögreen, B.; Strömbom, L.; et al. The Real-time polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Asp. Med. 2006, 27, 95–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.; Roy-Chowdhuri, S. Quantitative Real-Time PCR: Recent Advances. In Clinical Applications of PCR; Luthra, R., Singh, R.R., Patel, K.P., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1392, pp. 161–176. ISBN 978-1-4939-3358-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bustin, S. Absolute quantification of mRNA Using Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Assays. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000, 25, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, D.; Meulia, T.; Fenster, S. Real-Time PCR. In Current Protocols Essential Laboratory Techniques; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, L.F.; Piovezani, A.R.; Ivanov, D.A.; Yoshida, L.; Segal Floh, E.I.; Kato, M.J. Selection and validation of reference genes for measuring gene expression in piper species at different life stages using RT-qPCR analysis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 171, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Gao, Q.; Cheng, H.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yuan, X.; Bao, S.; Kuan, C.; Zhang, H. Optimal reference genes for gene expression analysis of overmating stress-induced aging and natural aging in male Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qian, Z.; Lu, W.; Ding, H.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Identification and characterization of reference genes for normalizing expression data from red swamp crawfish Procambarus clarkii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 21591–21605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Mu, B.-R.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, Q.-L.; Li, B.; Wang, D.-M.; Lu, M.-H. Research trends and development dynamics of qPCR-Based biomarkers: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis. In Molecular Biotechnology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lv, Y.; Cheng, P.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, C.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Xie, J.; Chen, J.; Shi, Q.; et al. Expression profiles of housekeeping genes and tissue-specific genes in different tissues of chinese sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis). Animals 2024, 14, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, E.; Levanon, E.Y. Human housekeeping genes, revisited. Trends Genet. 2013, 29, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozera, B.; Rapacz, M. Reference Genes in Real-Time PCR. J. Appl. Genet. 2013, 54, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunde, T.T.; Pedra, A.C.K.; De Oliveira, N.R.; Dellagostin, O.A.; Bohn, T.L.O. A systematic review on the selection of reference genes for gene expression studies in rodents: Are the classics the best choice? Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Hernandez, N.; Véliz, D.; Vega-Retter, C. Selection of suitable reference genes for gene expression analysis in gills and liver of fish under field pollution conditions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Lai, M. Actin, a reliable marker of internal control? Clin. Chim. Acta 2007, 385, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikand, K.; Singh, J.; Ebron, J.S.; Shukla, G.C. Housekeeping gene selection advisory: Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-Actin are targets of miR-644a. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Cao, J.; Niu, G.; Xia, L.; Zou, D.; Wang, F.; Xu, X.; Han, X.; et al. ICG: A wiki-driven knowledgebase of internal control genes for RT-qPCR normalization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D121–D126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, M.R.; Araújo, I.P.; Da Costa Arruda, W.; Lima, A.A.; Ságio, S.A.; Chalfun-Junior, A.; Barreto, H.G. RGeasy: A reference gene analysis tool for gene expression studies via RT-qPCR. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dammannagoda, L.K.; Pavasovic, A.; Prentis, P.J.; Hurwood, D.A.; Mather, P.B. Expression and characterization of digestive enzyme genes from hepatopancreatic transcripts from redclaw crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus). Aquacult Nutr. 2015, 21, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, C.; Martinez-Rodriguez, G.; Costas, B.; Mancera, J.M.; Fernandez-Boo, S.; Rodulfo, H.; De Donato, M. Shrimp immune response: A transcriptomic perspective. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 1136–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, Y.; Fu, H. Recent progress of male sexual differentiation and development in the oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense): A Review. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Shi, X.; Fang, S.; Zhang, Y.; You, C.; Ma, H.; Lin, F. Comparative transcriptome analysis combining smrt and ngs sequencing provides novel insights into sex differentiation and development in mud crab (Scylla paramamosain). Aquaculture 2019, 513, 734447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, M.; Levy, T.; Ventura, T.; Sagi, A. monosex populations of the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii—From a pre-molecular start to the Next Generation Era. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Fu, H.; Qiao, H.; Sun, S.; Zhang, W.; Jin, S.; Jiang, S.; Gong, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, Y. Validation and evaluation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in Macrobrachium nipponense. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, H.; Das, R.; Kumar, P.; Babu, G.; Javed, H.; Krishna, G.; Marappan, M.; Chaudhari, A. Characterization and evaluation of selected house-keeping genes for quantitative RT-PCR in Macrobrachium rosenbergii morphotypes. Fish. Technol. 2015, 52, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.-M.; Tao, Z.; Shen, C.; Qian, D.; Wang, C.-L.; Zhou, Q.-C.; Jin, S. β-Actin gene expression is variable among individuals and not suitable for normalizing mrna levels in Portunus trituberculatus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 81, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, C.R.; Valenti, W.C. Biology, Fisheries, and Aquaculture of the amazon river prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum: A Review. Nauplius 2009, 17, 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, L.D.S.; Silva, T.A.; Muniz, J.I.; Freire, F.A.M.; Pinheiro, A.P.; Moraes, S.A.S.N.D.; Alencar, C.E.R.D. Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda, Palaemonidae): Geographic distribution, new occurrences and biogeographic insights. Aquat. Biol. 2025, 34, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong-Carrillo, O.; Vega-Villasante, F.; Arencibia-Jorge, R.; Akintola, S.L.; Michán-Aguirre, L.; Cupul-Magaña, F.G. Research on the river shrimps of the genus Macrobrachium (Bate, 1868) (Decapoda: Caridea: Palaemonidae) with known or potential economic importance: Strengths and weaknesses shown through scientometrics. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2015, 43, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, G.M.; Abrunhosa, F.A.; Maciel, B.R.; Lutz, Í.; Sousa, J.d.S.A.d.L.; Maciel, C.M.T.; Maciel, C.R. In silico identification of the laccase-encoding gene in the transcriptome of the amazon river prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862). Genes 2024, 15, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, L.D.; de Moura, L.B.; de Lima, G.M.; Maciel, C.M.T.; Campelo, D.A.V.; Maciel, C.R. Amazon river prawn is able to express endogenous endo-β-1,4-glucanase and using cellulose as energy source. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 33, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.P.; Maciel, C.M.T.; Valenti, W.C.; Moraes-Valenti, P.; Sampaio, I.; Maciel, C.R. Prospection of putative genes for digestive enzymes based on functional genome of the hepatopancreas of Amazon river prawn. Acta Sci.-Anim. Sci. 2022, 44, e53894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.D.S.A.D.L.; Lima, G.M.D.; Maciel, B.R.; Lutz, Í.; Maciel, C.M.T.; Maciel, C.R. In silico characterization of acid phosphatase in the functional genome of the Amazon Prawn. Braz. J. Anim. Environ. Res. 2024, 7, e70373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babraham Bioinformatics. FastQC a Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. v. 0.12.0. 2023. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-Length transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, C.M.T. Transcriptomas do Macrobrachium amazonicum Desenvolvidos no Sequenciador Ion Torrent TM; Programa de Pós- Graduação em Genética e Biologia Molecular—Bioinformática da UFPA; UFPA: Belém, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. In Nucleic acids symposium series; Oxford Universiy Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; Volume 41, pp. 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; De Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, X.; Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W320–W324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, G.; Zhang, C.; Prado, M.G.; Paiardini, A. PyMod 2.0: Improvements in protein sequence-structure analysis and homology modeling within PyMOL. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, J.; Buso, N.; Gur, T.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Basutkar, P.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Potter, S.C.; Finn, R.D.; et al. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W636–W641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, D.; New, M.B. Biology. In Freshwater Prawn Culture; New, M.B., Valenti, W.C., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 18–40. ISBN 978-0-632-05602-6. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B. RefFinder: A Web-Based Tool for comprehensively analyzing and identifying reference genes. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, N.; Best, S.; Jiang, J.; Thein, S.L. Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using Real-Time PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W.; Tichopad, A.; Prgomet, C.; Neuvians, T.P. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: Bestkeeper—Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.L.; Jensen, J.L.; Ørntoft, T.F. Normalization of Real-Time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR Data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5245–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, research0034.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H. Ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics, v. 3.5.1; The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Chen, M.; Huang, J.-D.; Deng, H.K.; Dong, S.; Deng, W.; Tsang, S.L.; Huen, M.S.; Chen, L.; Zan, T.; Zhu, G.-X.; et al. Overexpression of eIF-5A2 in mice causes accelerated organismal aging by increasing chromosome instability. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, Q.; Li, X.; Chan, T.-Y.; Chu, K.H.; Gan, Z. Molecular phylogeny of the superfamily Palaemonoidea (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea) based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA reveals discrepancies with the current classification. Invertebr. Syst. 2013, 27, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Cormano, L.; Brisset, J.; Chan, T.-Y.; Corbari, L.; Puillandre, N.; Utge, J.; Zbinden, M.; Zuccon, D.; Samadi, S. An improved taxonomic sampling is a necessary but not sufficient condition for resolving inter-families relationships in Caridean Decapods. Genetica 2015, 143, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Iyengar, A.; Marins, L.F.; Biemar, F.; Hanley, S.; Maclean, N.; Smith, T.J.; Martial, J.A.; Muller, M. Gene structure and promoter function of a teleost ribosomal protein: A tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) L18 gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Struct. Expr. 2001, 1520, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, M.L.; Ammar, D.; Quispe, R.L.; Guzman, F.; Margis, R.; Nazari, E.M.; Müller, Y.M.R. Identification and evaluation of reference genes for expression studies by RT-qPCR during embryonic development of the emerging model organism, Macrobrachium olfersii. Gene 2017, 598, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.-J.; Dai, Z.-M.; Liu, J.; Yang, W.-J. Actin gene in prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii: Characteristics and differential tissue expression during embryonic development. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 140, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, J.; Du, J.; Li, F.; Xiang, J. Actin genes and their expression in pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2018, 293, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, D.L.; Verzi, M.P.; Burgents, J.E.; Tanner, C.A.; Glomski, K.; Lee, J.J.; Towle, D.W. Expression profiles of Na+,K+-ATPase during acute and chronic hypo-osmotic stress in the blue crab Callinectes sapidus. Biol. Bull. 2006, 211, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.M.; Reversade, B. Characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel band 4.1-like protein in zebrafish. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1997, 75, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wang, J.; Ji, G.; Zhang, X. Significant genes in response to low temperature in Fenneropenaeus chinensis screened through multiple transcriptome group comparisons. J. Therm. Biol. 2022, 107, 103198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portran, D.; Schaedel, L.; Xu, Z.; Théry, M.; Nachury, M.V. Tubulin acetylation protects long-lived microtubules against mechanical ageing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinji, J.; Miyanishi, H.; Kaneko, T.; Gotoh, H.; Kaneko, T. Appendage regeneration after autotomy is mediated by baboon in the crayfish Procambarus fallax f. virginalis Martin, Dorn, Kawai, Heiden and Scholtz, 2010 (Decapoda: Astacoidea: Cambaridae). J. Crustac. Biol. 2016, 36, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Ye, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Huang, H. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the fatty acid-binding protein (Sp-FABP) gene in the mud crab (Scylla paramamosain). Genet. Mol. Biol. 2013, 36, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Jiménez, L.; Peregrino-Uriarte, A.B.; Martínez-Quintana, J.A.; Yepiz-Plascencia, G. The Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase of the shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei: Molecular cloning, characterization and expression during hypoxia. Mar. Environ. Res. 2018, 138, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, D.; Poling, L.L.; Lyons-Weiler, M.; Hedges, S.B. The colonization of land by animals: Molecular phylogeny and divergence times among arthropods. BMC Biol. 2004, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, J.Y.; Sun, X.H.; Wu, R. Structure of two unlinked Drosophila melanogaster Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase genes. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 8220–8228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ortiz, R.; Fernández-Rosales, J.P.; García-Peña, M.F.; Hernández, A.; Espino-Saldaña, A.E.; Martínez-Torres, A. Altered motor activity and social behavior in zebrafish lacking the Hcn2b ion channel. Neuroscience 2025, 586, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Huang, B.; Zhang, G.; Li, L. Validation of housekeeping genes as internal controls for studying gene expression during pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) development by quantitative Real-Time PCR. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 34, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, J.; Wu, J.; Li, D.; Yang, X.; Huang, A.; Bu, G.; Meng, F.; Kong, F.; Cao, X.; et al. Transcriptome-based evaluation and validation of suitable housekeeping gene for quantification Real-Time PCR under specific experiment condition in teleost fishes. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 98, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.R.; Waldenström, J. With reference to reference genes: A systematic review of endogenous controls in gene expression studies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cline, S.D. Mitochondrial DNA damage and its consequences for mitochondrial gene expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 2012, 1819, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotrys, A.V.; Szczesny, R.J. Mitochondrial gene expression and beyond—Novel aspects of cellular physiology. Cells 2019, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mposhi, A. Unravelling the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Metabolic Diseases; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Leelatanawit, R.; Klanchui, A.; Uawisetwathana, U.; Karoonuthaisiri, N. Validation of reference genes for Real-Time PCR of reproductive system in the black tiger shrimp. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Yu, Q.; Li, X.; Ning, X.; Wang, J.; Zou, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Hu, J.; Hu, X.; et al. Identification of reference genes for qRT-PCR Analysis in yesso scallop Patinopecten yessoensis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.C.; Elizur, A.; Ventura, T. The decapod researcher’s guide to the galaxy of sex determination. Hydrobiologia 2018, 825, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, T.; Sagi, A. The “IAG-Switch”—A key controlling element in decapod crustacean sex differentiation. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurley, A.T.; Callard, G.V. Characterization of housekeeping genes in zebrafish: Male-female differences and effects of tissue type, developmental stage and chemical treatment. BMC Mol. Biol. 2008, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, M.; Sato, C.; Rogaeva, E. Segmental duplications in genome-wide significant loci and housekeeping genes; warning for GAPDH and ACTB. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 1710.e1–1710.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Redies, C. Histological evidence: Housekeeping genes Beta-actin and GAPDH are of limited value for normalization of gene expression. Dev. Genes. Evol. 2012, 222, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, W.-Y.; Yao, F.-J.; Tang, T.; Shi, S.-S. Evaluation of the expression stability of β-actin under bacterial infection in Macrobrachium nipponense. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Shi, W.; Pawar, R.A.; Liu, Y.; Xu, C.; Cong, W.; Hu, Q.; Lu, T.; et al. β-Actin is a useful internal control for tissue-specific gene expression studies using Quantitative Real-Time PCR in the half-smooth tongue sole cynoglossus semilaevis challenged with LPS or Vibrio anguillarum. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 29, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, W.C. Laboratory life history of the palaemonid shirmp Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller) (Decapoda, Palaemonidae). Crustaceana 1979, 37, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes-Riodades, P.M.C.; Valenti, W.C. Morphotypes in male amazon river prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture 2004, 236, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloubert, V.; Rink, L. Selection of an inadequate housekeeping gene leads to misinterpretation of target gene expression in zinc deficiency and zinc supplementation models. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2019, 56, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, T.; Killam, B.Y.; Grozdanović, M.; Dobosz-Bartoszek, M.; Loerke, J.; Bürger, J.; Mielke, T.; Copeland, P.R.; Simonović, M.; Spahn, C.M.T. Structure of the mammalian ribosome as it decodes the selenocysteine UGA codon. Science 2022, 376, 1338–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.V.; Rogers, S.L.; Carter, A.P. CryoET shows cofilactin filaments inside the microtubule lumen. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e57264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers, D.M.; Metcalf, A.E.; Talbot, P.; Hyman, B.C. Multiple lobster tubulin isoforms are encoded by a simple gene family. Gene 1996, 171, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriles, A.A.; Mills, A.; Muñoz-Alonso, M.; Gutiérrez, D.; Domínguez, J.M.; Hermoso, J.A.; Gago, F. Structural cues for understanding eEF1A2 moonlighting. ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 374–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, J.; Song, S.; Lin, Z. Structure of Apo-Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase from Palinurus versicolor. J. Struct. Biol. 2000, 130, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5′-3′) | Length (bp) | GC% | Ta (°C) | E (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIF | F: GAGACTTGGGCACAGAAATC | 115 | 50 | 61 | 97.14 | 0.9966 |

| R: TACTTCATGTTTGGCTTAGTAGC | 39.1 | 61 | ||||

| 18S | F: GATTAAGTCCCTGCCCTTTG | 110 | 50 | 60 | 95.97 | 0.9952 |

| R: GCTGGAAGAAACCACTAGAC | 50 | 60 | ||||

| RPL18 | F: TGTCCAAAATTAACAAGCCTC | 93 | 38.1 | 59 | 98.96 | 0.9975 |

| R: CCACAACAACAAAGATTCGC | 45 | 60 | ||||

| β-actin | F: CACGAGACCACCTACAATTC | 223 | 50 | 60 | 95.67 | 0.9816 |

| R: GAGAAGCCAAGATAGAACCG | 50 | 60 | ||||

| α-tub | F: CATTCCGATTGTGCCTTTATG | 94 | 42.9 | 60 | 100.57 | 0.9929 |

| R: TCAGGTTGGTGTATGATGGA | 41 | 61 | ||||

| EF1-α | F: TGTACCCATCATTCCCATTTC | 120 | 42.9 | 60 | 100.68 | 0.9918 |

| R: GTCTCGTATTCATAAGATCCACTC | 41.7 | 60 | ||||

| GAPDH | F: TCCAGGTCTTCAACGAAATG | 200 | 45 | 60 | 92.14 | 0.9801 |

| R: GTACTTCTCCAGGTTTACACC | 47.6 | 60 |

| Gene | Species | Nt | aa | % nt | Access NCBI | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIF | Macrobrachium amazonicum * | 2621 | 157 | - | PX278678.1 | Present study |

| EIF | Macrobrachium nipponense | 2872 | 210 | 95.5 | MH540106.1 | [23] |

| EIF | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 2291 | 157 | 96.9 | XM_067081428.1 | Unpublished |

| EIF | Palaemon carinicauda | 2303 | 204 | 89.5 | XM_068365025.1 | Unpublished |

| EIF | Procambarus clarkii | 1478 | 157 | 83.0 | KR135170.1 | [7] |

| EIF | Homarus americanus | 3222 | 157 | 82.4 | XM_042380784.1 | Unpublished |

| EIF | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum | 1573 | 153 | 80.9 | XM_033122722.1 | Unpublished |

| EIF | Rattus norvegicus | 4871 | 153 | 79.7 | XM_001063995.1 | [52] |

| 18S | Macrobrachium amazonicum * | 2272 | - | - | PX279125.1 | Present study |

| 18S | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 1844 | - | 96.2 | DQ642856.1 | Unpublished |

| 18S | Macrobrachium nipponense | 1902 | - | 96.5 | XR_010313754.1 | Unpublished |

| 18S | Palaemon carinicauda | 1902 | - | 96.4 | XR_011045428.1 | Unpublished |

| 18S | Macrobrachium superbum | 1885 | - | 96.4 | KC515055.1 | [53] |

| 18S | Palaemon gravieri | 1884 | - | 96.3 | KC515058.1 | [53] |

| 18S | Exopalaemon orientis | 1885 | - | 96.3 | KC515053.1 | [53] |

| 18S | Palaemon serrifer | 1884 | - | 96.3 | KC515060.1 | [53] |

| 18S | Caridina serratirostris | 1852 | - | 96.7 | KP725709.1 | [53] |

| 18S | Exopalaemon vietnamicus | 1884 | - | 96.1 | KC515054.1 | [53] |

| 18S | Palaemon pacificus | 1884 | - | 96.0 | KC515059.1 | [53] |

| 18S | Palaemon debilis | 1885 | - | 95.9 | KC515057.1 | [53] |

| 18S | Palaemon macrodactylus | 1855 | - | 96.3 | DQ642849.1 | Unpublished |

| 18S | Macrobrachium lanchesteri | 1852 | - | 96.2 | KP725754.1 | [54] |

| 18S | Danio rerio | 1887 | - | 82.5 | XR_012407109.1 | Unpublished |

| RPL18 | Macrobrachium amazonicum * | 630 | 188 | - | PX278679.1 | Present study |

| RPL18 | Macrobrachium nipponense | 672 | 188 | 96.5 | MH540112.1 | Unpublished |

| RPL18 | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 710 | 188 | 96.7 | XM_067089493.1 | Unpublished |

| RPL18 | Palaemon carinicauda | 657 | 188 | 89.3 | XM_068359494.1 | Unpublished |

| RPL18 | Procambarus clarkii | 665 | 188 | 74.0 | XM_045761550.2 | Unpublished |

| RPL18 | Oreochromis niloticus | 649 | 188 | 82.0 | NM_001279463.1 | [55] |

| β-actin | Macrobrachium amazonicum * | 1129 | 332 | - | PX278680.1 | Present study |

| β-actin | Macrobrachium amazonicum * | 689 | 229 | 99.5 | JX948081.1 | Unpublished |

| β-actin | Macrobrachium nipponense | 1324 | 376 | 97.1 | KY780298.1 | Unpublished |

| β-actin | Macrobrachium olfersii | 1131 | 376 | 96.9 | KY027067.1 | [56] |

| β-actin | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 1281 | 376 | 96.4 | AY626840.1 | [57] |

| β-actin | Exopalaemon carinicauda | 1335 | 376 | 91.1 | JQ045354.1 | Unpublished |

| β-actin | Lysmata vittata | 1131 | 376 | 89.3 | MT114194.1 | Unpublished |

| β-actin | Marsupenaeus japonicus | 1327 | 376 | 87.4 | AB055975.1 | Unpublished |

| β-actin | Penaeus vannamei | 1249 | 376 | 87.1 | MF627840.1 | [58] |

| β-actin | Fenneropenaeus chinensis | 1358 | 376 | 87.1 | DQ205426.1 | Unpublished |

| β-actin | Scylla paramamosain | 1358 | 376 | 88.5 | GU992421.1 | Unpublished |

| β-actin | Callinectes sapidus | 1338 | 376 | 88.1 | DQ084066.1 | [59] |

| β-actin | Portunus trituberculatus | 1382 | 376 | 87.9 | KC131030.1 | Unpublished |

| β-actin | Eriocheir sinensis | 1425 | 376 | 86.9 | KY356885.1 | Unpublished |

| β-actin | Danio rerio | 1143 | 375 | 87.0 | AF025305.1 | [60] |

| α-tub | Macrobrachium amazonicum * | 1700 | 455 | - | PX278681.1 | Present study |

| α-tub | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 2312 | 451 | 93.5 | XM_067133707.1 | Unpublished |

| α-tub | Macrobrachium nipponense | 1172 | 356 | 92.5 | MH540110.1 | Unpublished |

| α-tub | Palaemon carinicauda | 1664 | 451 | 86.4 | XM_068357483.1 | Unpublished |

| α-tub | Portunus trituberculatus | 2106 | 450 | 83.9 | XM_045281753.1 | Unpublished |

| α-tub | Penaeus chinensis | 1629 | 451 | 83.5 | MW486011.1 | [61] |

| α-tub | Penaeus indicus | 1673 | 451 | 83.4 | XM_063750237.1 | Unpublished |

| α-tub | Penaeus vannamei | 2211 | 451 | 83.3 | XM_027367265.2 | Unpublished |

| α-tub | Bos taurus | 1921 | 451 | 82.7 | NM_001166505.1 | [62] |

| EF1-α | Macrobrachium amazonicum * | 1795 | 461 | - | PX278682.1 | Present study |

| EF1-α | Macrobrachium nipponense | 1762 | 461 | 97.9 | XM_064243189.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 1386 | 461 | 97.7 | OR130524.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Procambarus clarkii | 1673 | 461 | 83.1 | XM_045749314.2 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Penaeus monodon | 1608 | 461 | 83.0 | MG775229.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Procambarus fallax | 1568 | 461 | 82.7 | LC035460.1 | [63] |

| EF1-α | Homarus americanus | 1633 | 461 | 82.5 | XM_042379195.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Penaeus japonicus | 1550 | 461 | 83.1 | AB458256.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Penaeus vannamei | 1658 | 461 | 82.8 | XM_027373349.2 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Penaeus indicus | 1634 | 461 | 82.8 | XM_063731077.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Penaeus chinensis | 1652 | 461 | 82.7 | XM_047615957.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Cherax quadricarinatus | 1660 | 461 | 82.1 | XM_070101441.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Panulirus ornatus | 1656 | 461 | 82.1 | XM_071679762.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Portunus trituberculatus | 1633 | 461 | 82.6 | KU361820.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Scylla paramamosain | 1559 | 461 | 81.9 | JQ824130.1 | [64] |

| EF1-α | Macrobrachium olfersii | 1242 | 413 | 84.5 | KY027069.1 | [56] |

| EF1-α | Eriocheir sinensis | 2050 | 461 | 80.9 | KY356884.1 | Unpublished |

| EF1-α | Epinephelus lanceolatus | 1607 | 462 | 76.8 | XM_033637922.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Macrobrachium amazonicum * | 1652 | 333 | - | PX278683.1 | Present study |

| GAPDH | Macrobrachium nipponense | 1651 | 333 | 89.1 | MH540109.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 1002 | 333 | 95.6 | MH219928.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Macrobrachium olfersii | 1002 | 333 | 94.2 | KY027066.1 | [56] |

| GAPDH | Palaemon carinicauda | 1514 | 333 | 86.3 | KX893516.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Penaeus japonicus | 1826 | 449 | 86.9 | XM_043022172.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Penaeus indicus | 1501 | 333 | 86.1 | XM_063750341.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Penaeus monodon | 1711 | 414 | 85.7 | XM_037920434.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Penaeus chinensis | 1761 | 430 | 85.7 | XM_047617625.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Penaeus vannamei | 1492 | 332 | 86.0 | MG787341.1 | [65] |

| GAPDH | Gammarus locusta | 1264 | 334 | 83.5 | FM165079.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Panulirus ornatus | 1759 | 334 | 82.8 | XM_071689634.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Portunus trituberculatus | 1457 | 334 | 80.9 | EU919707.1 | Unpublished |

| GAPDH | Callinectes sapidus | 888 | 296 | 80.5 | AAS02313.1 | [66] |

| GAPDH | Drosophila melanogaster | 2141 | 332 | 78.0 | M11254.1 | [67] |

| GAPDH | Danio rerio | 1329 | 333 | 69.2 | NM_001115114.1 | [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lima, G.M.d.; Rodrigues, M.A.L.; Paixão, R.V.; Lutz, Í.; Aviz, M.A.B.; Sousa, J.d.S.A.d.L.; Maciel, B.R.; Queiroz, L.D.; Maciel, C.M.T.; Sampaio, I.; et al. Identification and Validation of Tissue-Specific Housekeeping Markers for the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862). Genes 2026, 17, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010026

Lima GMd, Rodrigues MAL, Paixão RV, Lutz Í, Aviz MAB, Sousa JdSAdL, Maciel BR, Queiroz LD, Maciel CMT, Sampaio I, et al. Identification and Validation of Tissue-Specific Housekeeping Markers for the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862). Genes. 2026; 17(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima, Gabriel Monteiro de, Mônica Andressa Leite Rodrigues, Rômulo Veiga Paixão, Ítalo Lutz, Manoel Alessandro Borges Aviz, Janieli do Socorro Amorim da Luz Sousa, Bruna Ramalho Maciel, Luciano Domingues Queiroz, Carlos Murilo Tenório Maciel, Iracilda Sampaio, and et al. 2026. "Identification and Validation of Tissue-Specific Housekeeping Markers for the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862)" Genes 17, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010026

APA StyleLima, G. M. d., Rodrigues, M. A. L., Paixão, R. V., Lutz, Í., Aviz, M. A. B., Sousa, J. d. S. A. d. L., Maciel, B. R., Queiroz, L. D., Maciel, C. M. T., Sampaio, I., Varela, E. S., & Maciel, C. R. (2026). Identification and Validation of Tissue-Specific Housekeeping Markers for the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862). Genes, 17(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010026