Transcriptome Profiling of the Anterior Cingulate Cortex in a CFA-Induced Inflammatory Pain Model Identifies ECM-Related Genes in a Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition and Processing

2.2. Experimental Animals

2.3. GO and KEGG Functional Enrichment Analysis

2.4. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

2.5. PPI Network Construction and Hub Gene Identification

2.6. Random Forest Analysis for Gene Ranking

2.7. Establishment of the CFA-Induced Inflammatory Pain Model and Tissue Collection

2.8. Behavioral Tests

2.8.1. Assessment of Mechanical Allodynia (Von Frey Test)

2.8.2. Assessment of Thermal Hyperalgesia

2.8.3. Measurement of Paw Edema

2.9. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.9.1. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

2.9.2. qPCR Detection

2.10. Ethical Statement

3. Results

3.1. Dataset Selection and Differential Gene Expression

3.2. Functional Annotation

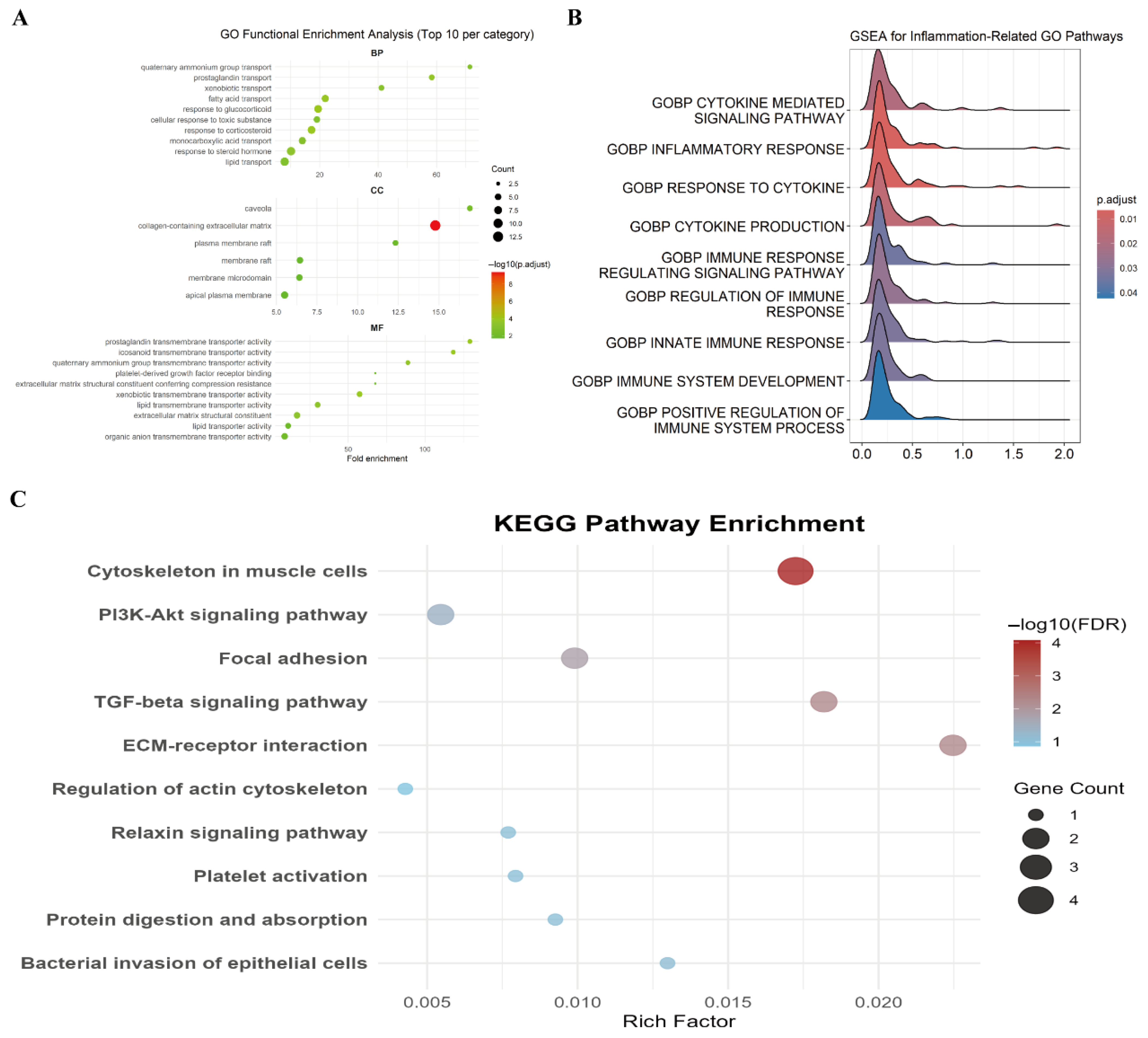

3.2.1. GO Enrichment Analysis

3.2.2. GSEA

3.2.3. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

3.3. PPI Network and Machine Learning Analysis

3.4. Experimental Validation of Hub Gene Expression

3.4.1. CFA Model and Behavioral Assessment

3.4.2. qPCR Validation of Gene Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Y.; Chen, H.; Lv, W.; Wei, S.; Zou, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; She, W.; Yuan, L.; Tao, J.; et al. Global, regional and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis from 1990 to 2021, with projections of incidence to 2050: A systematic and comprehensive analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2021. Biomark. Res. 2025, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyand, C.M.; Goronzy, J.J. The immunology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesemann, N.; Margerie, D.; Asbrand, C.; Rehberg, M.; Savova, V.; Agueusop, I.; Klemmer, D.; Ding-Pfennigdorff, D.; Schwahn, U.; Dudek, M.; et al. Additive efficacy of a bispecific anti–TNF/IL-6 nanobody compound in translational models of rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabq4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.V.; Schett, G.; Steffen, U. Autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: Historical background and novel findings. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 63, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletaha, D.; Smolen, J.S. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: A review. JAMA 2018, 320, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerschbaumer, A.; Sepriano, A.; Smolen, J.S.; van der Heijde, D.; Dougados, M.; van Vollenhoven, R.; McInnes, I.B.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Burmester, G.R.; de Wit, M.; et al. Efficacy of pharmacological treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic literature research informing the 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figus, F.A.; Piga, M.; Azzolin, I.; McConnell, R.; Iagnocco, A. Rheumatoid arthritis: Extra-articular manifestations and comorbidities. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malange, K.F.; Navia-Pelaez, J.M.; Dias, E.V.; Lemes, J.B.P.; Choi, S.-H.; Dos Santos, G.G.; Yaksh, T.L.; Corr, M. Macrophages and glial cells: Innate immune drivers of inflammatory arthritic pain perception from peripheral joints to the central nervous system. Front. Pain Res. 2022, 3, 1018800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hou, N.; Cheng, W.; Lu, X.; Wang, M.; Bai, S.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhang, P.; et al. MiR-378 exaggerates angiogenesis and bone erosion in collagen-induced arthritis mice by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.D.; Luo, Y.J.; Su, W.K.; Ge, J.; Crowther, A.; Chen, Z.-K.; Wang, L.; Lazarus, M.; Liu, Z.-L.; Qu, W.-M.; et al. Anterior cingulate cortex projections to the dorsal medial striatum underlie insomnia associated with chronic pain. Neuron 2024, 112, 1328–1341.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Liu, Y.; Shao, S.; Song, W.; Chen, X.-H.; Dong, Y.-T.; Zhang, Y.-M. The microglial innate immune receptors TREM-1 and TREM-2 in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) drive visceral hypersensitivity and depressive-like behaviors following DSS-induced colitis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 112, 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Cai, B.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X. Somatosensory neuron types and their neural networks as revealed via single-cell transcriptomics. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 654–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, J.; Xue, X.; Dai, T.; Zhu, W.; Jiao, S.; Wu, H.; Meng, Q. Identification of aging-related genes in diagnosing osteoarthritis via integrating bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Aging 2024, 16, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Yue, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, S.; Li, D.; Zhen, F.; Liu, L.; Zhu, H.; Xie, M. Anemoside B4 alleviates arthritis pain via suppressing ferroptosis-mediated inflammation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Wang, F.; He, X.; Zhou, K.; Wu, X.; Wu, X. Protective effect of corynoline on the CFA induced rheumatoid arthritis via attenuation of oxidative and inflammatory mediators. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chinnathambi, A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Bai, L. Copper oxide nanoparticles from Rabdosia rubescens attenuates the complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) induced rheumatoid arthritis in rats via suppressing the inflammatory proteins COX-2/PGE2. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 5639–5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-J.; Zhang, K.; Sun, T.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.-Y.; Yang, L.; Yang, Q.; Li, Y.-J.; Liu, S.-B.; Zhao, M.-G.; et al. Epigenetic suppression of liver X receptor β in anterior cingulate cortex by HDAC5 drives CFA-induced chronic inflammatory pain. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga, K.; Shimoyama, S. The Expression Profiling of the Anterior Cingulate Cortex and Hippocampus in Chronic Inflammatory Pain Mice—Gene Expression Omnibus 2021, GSE147216. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE147216 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Barrett, T.; Wilhite, S.E.; Ledoux, P.; Evangelista, C.; Kim, I.F.; Tomashevsky, M.; Marshall, K.A.; Phillippy, K.H.; Sherman, P.M.; Holko, M.; et al. NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data sets—Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D991–D995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, S.P.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Cai, Y.-D. Prediction and analysis of essential genes using the enrichments of gene ontology and KEGG pathways. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleino, I.; Frolovaitė, P.; Suomi, T.; Elo, L.L. Computational solutions for spatial transcriptomics. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 4870–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynal, L.; Marin, J.M.; Pudlo, P.; Ribatet, M.; Robert, C.P.; Estoup, A. ABC Random Forests for Bayesian parameter inference. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1720–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 35892-2018; Guidelines for Ethical Review of Laboratory Animal Welfare. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Darvish-Ghane, S.; Baumbach, J.; Martin, L.J. Influence of inflammatory pain and dopamine on synaptic transmission in the mouse ACC. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.; Dityatev, A. Crosstalk between glia, extracellular matrix and neurons. Brain Res. Bull. 2018, 136, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscitti, P.; Liakouli, V.; Panzera, N.; Angelucci, A.; Berardicurti, O.; Di Nino, E.; Navarini, L.; Vomero, M.; Ursini, F.; Mauro, D.; et al. Tofacitinib may inhibit myofibroblast differentiation from rheumatoid-fibroblast-like synoviocytes induced by TGF-β and IL-6. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, W.; Pan, Y.; Wei, W.; Gerner, S.T.; Huber, S.; Juenemann, M.; Butz, M.; Bähr, M.; Huttner, H.B.; Doeppner, T.R. TGF-β1 decreases microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and lipid droplet accumulation in an in vitro stroke model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, P.; Zhou, S.; Cao, C.; Zhao, W.; Zeng, L.; Rong, X. The elucidation of the anti-inflammatory mechanism of EMO in rheumatoid arthritis through an integrative approach combining bioinformatics and experimental verification. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1195567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.H.; Chen, S.C.; Chen, H.Y.; Wu, C.B.; Huang, W.T.; Chiang, H.Y. Astrocyte-associated fibronectin promotes the proinflammatory phenotype of astrocytes through β1 integrin activation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 125, 103848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, D.A.; Moon, S.A.; Lee, S.E.; Lee, S.H.; Koh, J.-M. Lumican, an exerkine, protects against skeletal muscle loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Peng, J.; Pang, J.; Guo, K.; Zhang, L.; Yin, S.; Zhou, J.; Gu, L.; Tu, T.; Mu, Q.; et al. Biglycan regulates neuroinflammation by promoting M1 microglial activation in early brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurochem. 2020, 152, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupczyk, D.; Bilski, R.; Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Mądra-Gackowska, K.; Studzińska, R. The Role of Diet in Modulating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Ankylosing Spondylitis, and Psoriatic Arthritis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Forward Primers | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| M-Actb | CCACCATGTACCCAGGCATT | CAGCTCAGTAACAGTCCGCC |

| Fn1 | GCTCAGCAAATCGTGCAGC | CTAGGTAGGTCCGTTCCCACT |

| Bgn | TGCCATGTGTCCTTTCGGTT | CAGGTCTAGCAGTGTGGTGTC |

| Lum | CTCTTGCCTTGGCATTAGTCG | GGGGGCAGTTACATTCTGGTG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xie, G.-X.; Li, J.-M.; Liu, B.-T.; Wang, J.-T.; Xie, L.-S.; Xiong, X.-Y.; Wu, Q.-F.; Yu, S.-G. Transcriptome Profiling of the Anterior Cingulate Cortex in a CFA-Induced Inflammatory Pain Model Identifies ECM-Related Genes in a Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Genes 2026, 17, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010015

Xie G-X, Li J-M, Liu B-T, Wang J-T, Xie L-S, Xiong X-Y, Wu Q-F, Yu S-G. Transcriptome Profiling of the Anterior Cingulate Cortex in a CFA-Induced Inflammatory Pain Model Identifies ECM-Related Genes in a Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Genes. 2026; 17(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Guang-Xin, Jian-Mei Li, Bai-Tong Liu, Jiang-Tao Wang, Lu-Shuang Xie, Xiao-Yi Xiong, Qiao-Feng Wu, and Shu-Guang Yu. 2026. "Transcriptome Profiling of the Anterior Cingulate Cortex in a CFA-Induced Inflammatory Pain Model Identifies ECM-Related Genes in a Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis" Genes 17, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010015

APA StyleXie, G.-X., Li, J.-M., Liu, B.-T., Wang, J.-T., Xie, L.-S., Xiong, X.-Y., Wu, Q.-F., & Yu, S.-G. (2026). Transcriptome Profiling of the Anterior Cingulate Cortex in a CFA-Induced Inflammatory Pain Model Identifies ECM-Related Genes in a Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Genes, 17(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010015