Brain Matters in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: DMD Mutation Sites and Their Association with Neurological Comorbidities Through Isoform Impairment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Clinical Assessment

- The neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) including intellectual disability (ID), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and language and/or speech disorders (LSD). Cognitive ability was measured using Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children (WISC), Raven’s Progressive Matrices, or Mental Developmental Scales depending on the patient’s age. Patients were divided into intellectually normal or disabled, based either on the IQ or DQ at the moment of the assessment. A small number of patients had severe developmental delay and were not able to complete these scales therefore they were directly categorized into the intellectual disability group. The diagnosis of ADHD and ASD was established by pediatric psychiatrists based on criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV-TR and DSM V). Patients were classified as having language and/or speech disorders based on Verbal Comprehension Index scores from the Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children (WISC) and based on the healthcare professionals’ reports at presentation.

- The behavioral emotional (BE) group was divided in two: a. the externalizing symptoms (ES) group including oppositional/aggressive behavior, anger problems, and behavioral outbursts—analyzed by pediatric neurologists at presentation or reported by the family; and b. the internalizing symptoms (IS) group including anxiety and depression—diagnosis was established by pediatric psychiatrists based on the criteria of the DSM IV-TR/DSM V.

- The diagnosis of epilepsy was established based on history, clinical aspects of seizures, and EEG evaluation findings. Seizure diagnosis respected the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification [35,36,37]. Patients with febrile seizures, family history of epilepsy, or other known etiology for the seizures were excluded from this category.

2.3. Genetic Analysis

2.3.1. Structural Classification of the Identified DMD Variants

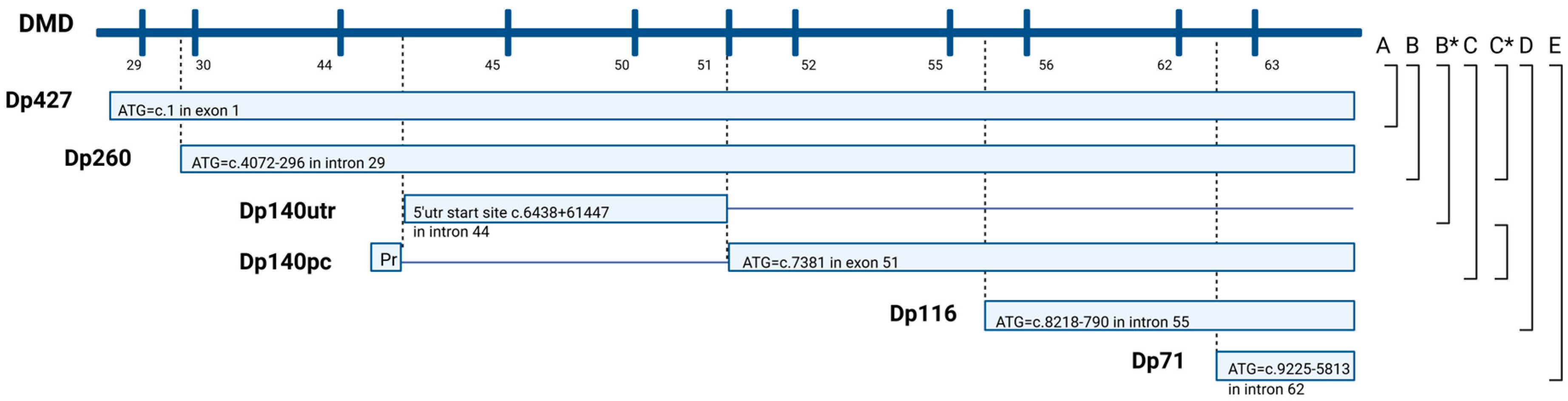

2.3.2. Functional Classification of the Identified DMD Variants

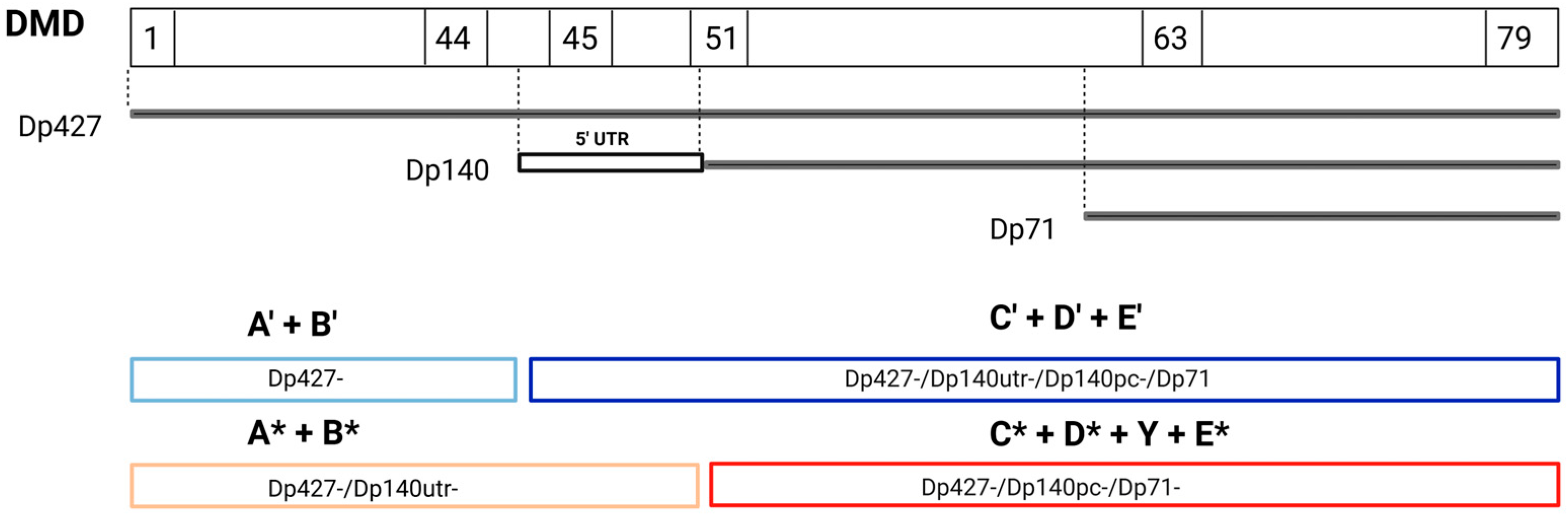

2.3.3. Functional Versus Structural Comparison and Study of Dp140 5′ UTR Variants

2.3.4. Genotype–Phenotype Correlations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Results

3.2. Structural Classification of the Identified DMD Variants

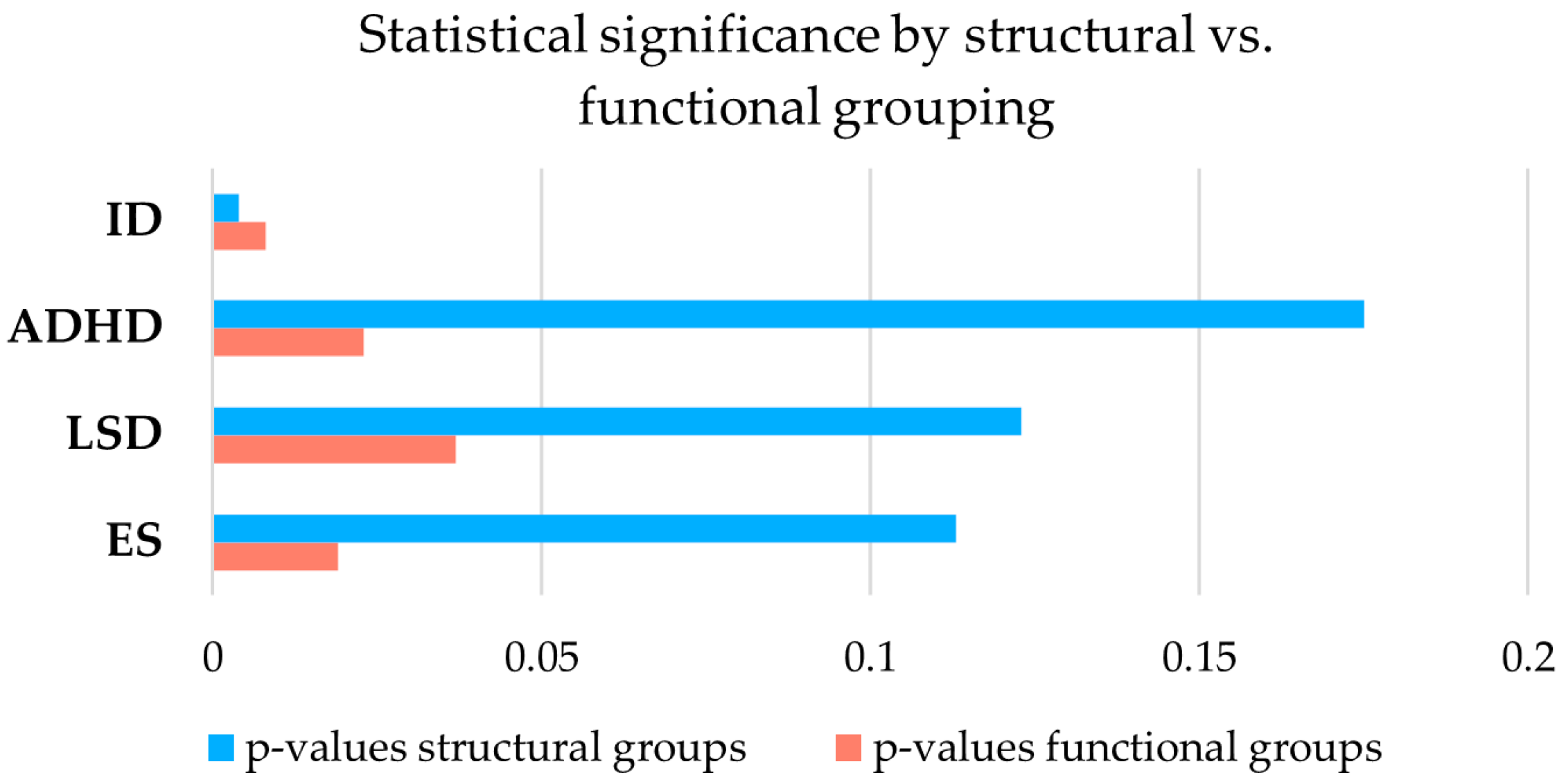

3.3. Functional Versus Structural Comparison and Study of Dp140 5′UTR Variants

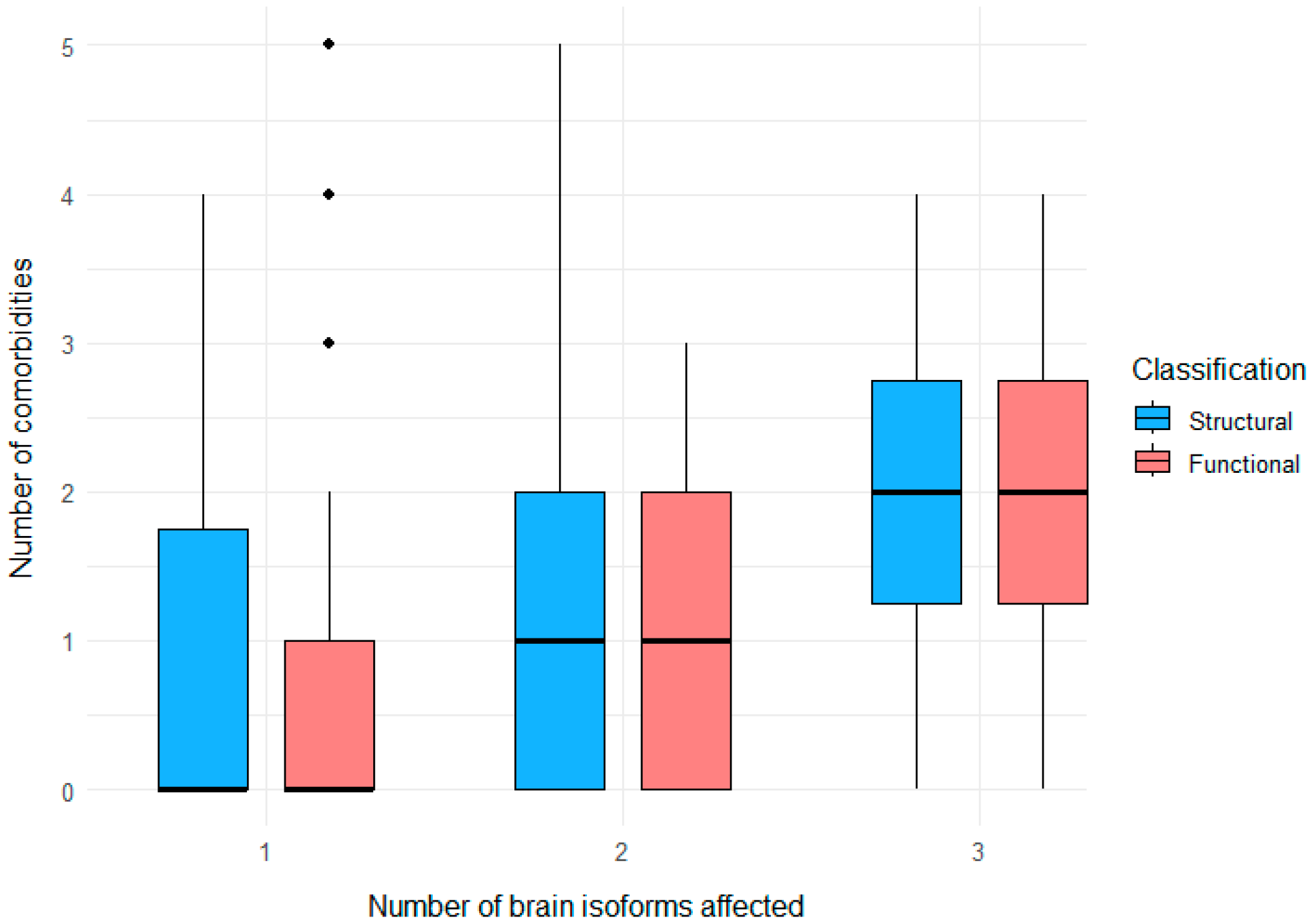

3.4. Clustering of Neurological and Psychiatric Comorbidities

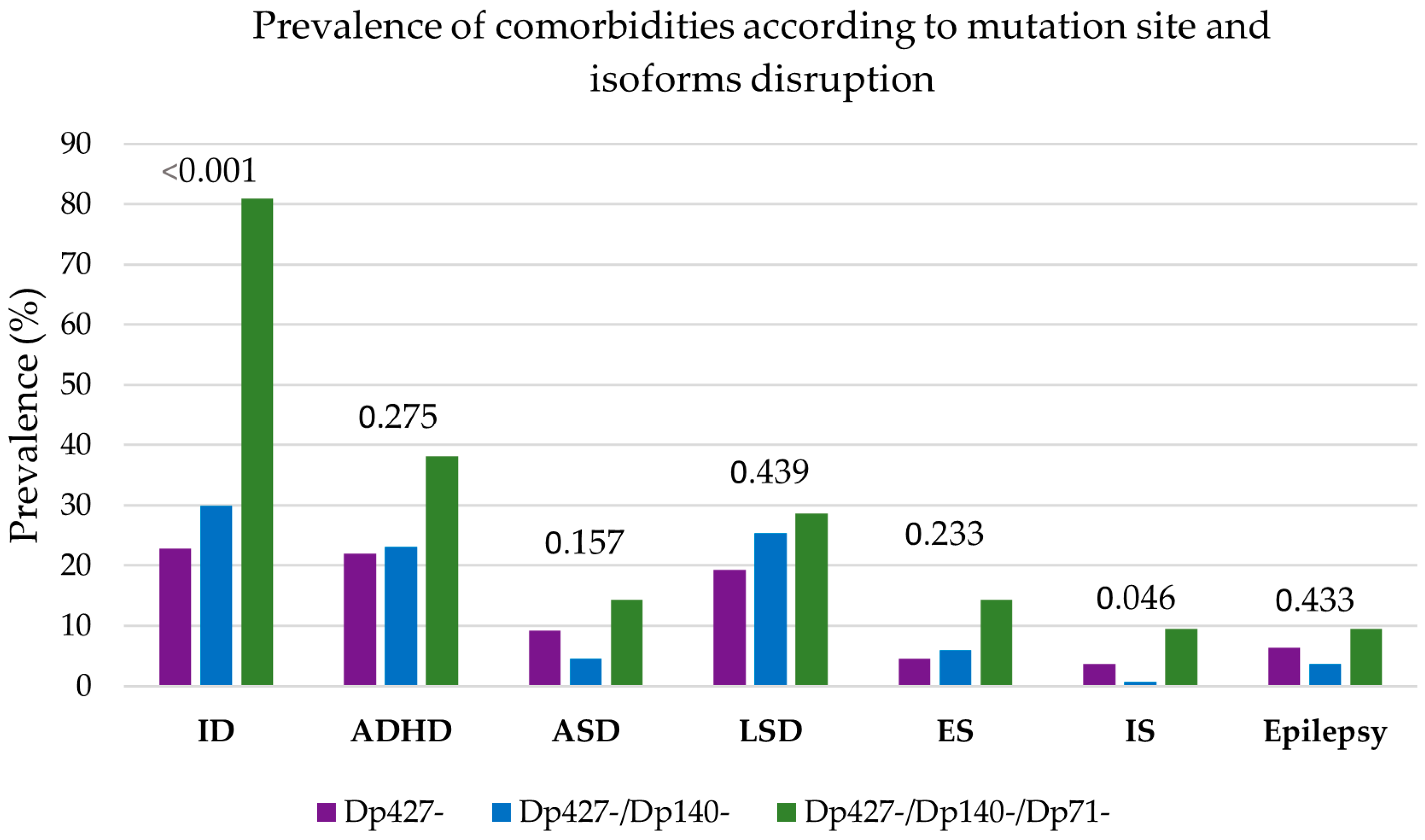

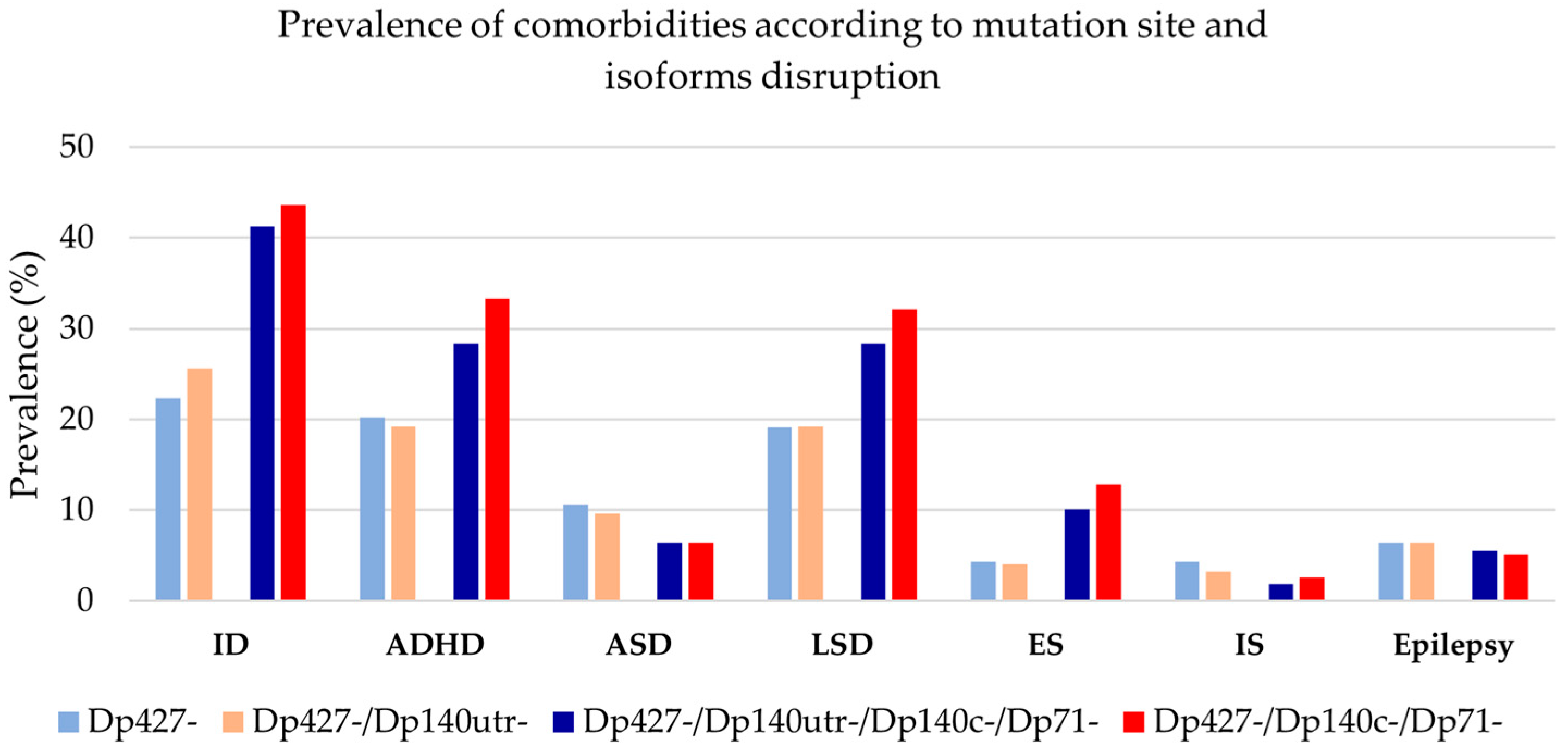

3.5. Genotype–Phenotype Correlations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emery, A.E. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet 2002, 359, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; Head, S.I.; Rae, C.; Morley, J.W. Brain function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Brain 2002, 125, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, S.; Voudouris, N.J.; Greenwood, K.M. Intelligence and Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Full-scale, verbal, and performance intelligence quotients. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2001, 43, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotton, S.M.; Voudouris, N.J.; Greenwood, K.M. Association between intellectual functioning and age in children and young adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Further results from a meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005, 47, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchenne de Boulogne, G.B.A. Studies on pseudohypertrophic muscular paralysis or myosclerotic paralysis. In Neurological Classics; Wilkins, R.H., Brody, I.A., Eds.; American Association of Neurological Surgeons: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ciafaloni, E.; Fox, D.J.; Pandya, S.; Westfield, C.P.; Puzhankara, S.; Romitti, P.A.; Mathews, K.D.; Miller, T.M.; Matthews, D.J.; Miller, L.A.; et al. Delayed diagnosis in duchenne muscular dystrophy: Data from the Muscular Dystrophy Surveillance, Tracking, and Research Network (MD STARnet). J. Pediatr. 2009, 155, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, M.; Hoffman, E.P.; Bertelson, C.J.; Monaco, A.P.; Feener, C.; Kunkel, L.M. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell 1987, 50, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntoni, F.; Torelli, S.; Ferlini, A. Dystrophin and mutations: One gene, several proteins, multiple phenotypes. Lancet Neurol. 2003, 2, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidov, H.G.; Byers, T.J.; Watkins, S.C.; Kunkel, L.M. Localization of dystrophin to postsynaptic regions of central nervous system cortical neurons. Nature 1990, 348, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidov, H.G.; Byers, T.J.; Kunkel, L.M. The distribution of dystrophin in the murine central nervous system: An immunocytochemical study. Neuroscience 1993, 54, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelly, J.; Hamard, G.; Koulakoff, A.; Kaplan, J.C.; Kahn, A.; Berwald-Netter, Y. Dystrophin gene transcribed from different promoters in neuronal and glial cells. Nature 1990, 344, 64–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.J.; Weir, A.; Newey, S.E.; Davies, K.E. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 291–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, V.N.; Nguyen, T.M.; Morris, G.E.; Karges, W.; Pillers, D.A.; Ray, P.N. A novel dystrophin isoform is required for normal retinal electrophysiology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995, 4, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadoulet-Puccio, H.M.; Kunkel, L.M. Dystrophin and its isoforms. Brain Pathol. 1996, 6, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardoni, A.; Felisari, G.; Sironi, M.; Comi, G.; Lai, M.; Robotti, M.; Bresolin, N. Loss of Dp140 regulatory sequences is associated with cognitive impairment in dystrophinopathies. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2000, 10, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, T.J.; Lidov, H.G.; Kunkel, L.M. An alternative dystrophin transcript specific to peripheral nerve. Nat. Genet. 1993, 4, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, R.C.; Morris, G.E.; Howard, P.L.; Klamut, H.J.; Ray, P.N. Expression and synthesis of alternatively spliced variants of Dp71 in adult human brain. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2000, 10, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotti, V.; Mandy, W.P.; Scoto, M.; Pane, M.; Deconinck, N.; Messina, S.; Mercuri, E.; Skuse, D.H.; Muntoni, F. Neurodevelopmental, emotional, and behavioural problems in Duchenne muscular dystrophy in relation to underlying dystrophin gene mutations. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moizard, M.P.; Billard, C.; Toutain, A.; Berret, F.; Marmin, N.; Moraine, C. Are Dp71 and Dp140 brain dystrophin isoforms related to cognitive impairment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy? Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998, 80, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, M.G.; Lorusso, M.L.; Civati, F.; Comi, G.P.; Magri, F.; Del Bo, R.; Guglieri, M.; Molteni, M.; Turconi, A.C.; Bresolin, N. Neurocognitive profiles in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and gene mutation site. Pediatr. Neurol. 2011, 45, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Betts, G.A.; Maroulis, S.; Gilissen, C.; Pedersen, R.L.; Mowat, D.R.; Johnston, H.M.; Buckley, M.F. Dystrophin gene mutation location and the risk of cognitive impairment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.E.; Simmons, C.; Nguyen, T.M. Apo-dystrophins (Dp140 and Dp71) and dystrophin splicing isoforms in developing brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 215, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorusso, M.L.; Civati, F.; Molteni, M.; Turconi, A.C.; Bresolin, N.; D’Angelo, M.G. Specific profiles of neurocognitive and reading functions in a sample of 42 Italian boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Child. Neuropsychol. 2013, 19, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, M.; Lombardo, M.E.; Alfieri, P.; D’Amico, A.; Bianco, F.; Vasco, G.; Piccini, G.; Mallardi, M.; Romeo, D.M.; Ricotti, V.; et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and cognitive function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Phenotype-genotype correlation. J. Pediatr. 2012, 161, 705–709.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, J.G.; Vles, J.S. Neuropsychiatric disorders in males with duchenne muscular dystrophy: Frequency rate of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, and obsessive--compulsive disorder. J. Child Neurol. 2008, 23, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, V.J.; Cyrulnik, S.E.; Fee, R.J.; Batchelder, A.; Kiefel, J.M.; Goldstein, E.M.; Kaufmann, P.; De Vivo, D.C. Association of autistic spectrum disorders with dystrophinopathies. Pediatr. Neurol. 2009, 41, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Kuban, K.C.; Allred, E.; Shapiro, F.; Darras, B.T. Association of Duchenne muscular dystrophy with autism spectrum disorder. J. Child. Neurol. 2005, 20, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmahkasih, A.J.; Rybalsky, I.; Tian, C.; Shellenbarger, K.C.; Horn, P.S.; Lambert, J.T.; Wong, B.L. Neurodevelopmental, behavioral, and emotional symptoms common in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 2020, 61, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, F.; Muntoni, F.; Dubowitz, V. Epilepsy in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies. Eur. J. Paediatr. 1997, 1, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemadifar, M.; Molaei, S. Epilepsy in boys with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2004, 3, 116–199. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, M.; Messina, S.; Bruno, C.; D’amico, A.; Villanova, M.; Brancalion, B.; Sivo, S.; Bianco, F.; Striano, P.; Battaglia, D.; et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy and epilepsy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2013, 23, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriksen, R.G.F.; Vles, J.S.H.; Aalbers, M.W.; Chin, R.F.M.; Hendriksen, J.G.M. Brain-related comorbidities in boys and men with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A descriptive study. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2018, 22, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnkrant, D.J.; Bushby, K.; Bann, C.M.; Apkon, S.D.; Blackwell, A.; Brumbaugh, D.; Case, L.E.; Clemens, P.R.; Hadjiyannakis, S.; Pandya, S.; et al. DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: Diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 251–267, Erratum in Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 495. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30125-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnkrant, D.J.; Bushby, K.; Bann, C.M.; Apkon, S.D.; Blackwell, A.; Colvin, M.K.; Cripe, L.; Herron, A.R.; Kennedy, A.; Kinnett, K.; et al. DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: Primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. From the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 1981, 22, 489–501. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.S.; Cross, J.H.; French, J.A.; Higurashi, N.; Hirsch, E.; Jansen, F.E.; Lagae, L.; Moshé, S.L.; Peltola, J.; Roulet Perez, E.; et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffer, I.E.; Berkovic, S.; Capovilla, G.; Connolly, M.B.; French, J.; Guilhoto, L.; Hirsch, E.; Jain, S.; Mathern, G.W.; Moshé, S.L.; et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, T.; Sack, L.M.; Arjona, D.; Tan, D.; Mei, H.; Cui, H.; Gao, H.; Bean, L.J.; Ankala, A.; Del Gaudio, D.; et al. Adapting ACMG/AMP sequence variant classification guidelines for single-gene copy number variants. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 336–344, Erratum in Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 670–671. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0725-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangarajh, M.; Hendriksen, J.; McDermott, M.P.; Martens, W.; Hart, K.A.; Griggs, R.C. Relationships between DMD mutations and neurodevelopment in dystrophinopathy. Neurology 2019, 93, e1597–e1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, P.; Nobile, M.; Tesei, A.; Civati, F.; Gandossini, S.; Mani, E.; Molteni, M.; Bresolin, N.; D’Angelo, G. Assessing mental health in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Emotional, behavioural and neurodevelopmental profile in an Italian clinical sample. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2017, 21, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banihani, R.; Smile, S.; Yoon, G.; Dupuis, A.; Mosleh, M.; Snider, A.; McAdam, L. Cognitive and Neurobehavioral Profile in Boys With Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J. Child. Neurol. 2015, 30, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perronnet, C.; Vaillend, C. Dystrophins, utrophins, and associated scaffolding complexes: Role in mammalian brain and implications for therapeutic strategies. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 849426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, M.; Zushida, K.; Yoshida, M.; Maekawa, M.; Kamichi, S.; Yoshida, M.; Sahara, Y.; Yuasa, S.; Takeda, S.I.; Wada, K. A deficit of brain dystrophin impairs specific amygdala GABAergic transmission and enhances defensive behaviour in mice. Brain 2009, 132, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, F.; Candelario-Martinez, A.; Billard, J.M.; Avital, A.; Khelfaoui, M.; Rozenvald, Y.; Guegan, M.; Mornet, D.; Jaillard, D.; Nudel, U.; et al. Role of mental retardation-associated dystrophin-gene product Dp71 in excitatory synapse organization, synaptic plasticity and behavioral functions. PLoS ONE 2008, 4, e6574, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2010, 5. https://doi.org/10.1371/annotation/1cf456c8-c517-4f04-9e98-8f3ee3b29ce3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidov, H.G.; Selig, S.; Kunkel, L.M. Dp140: A novel 140 kDa CNS transcript from the dystrophin locus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995, 4, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doorenweerd, N.; Mahfouz, A.; van Putten, M.; Kaliyaperumal, R.; t’Hoen, P.A.; Hendriksen, J.G.; Aartsma-Rus, A.M.; Verschuuren, J.J.; Niks, E.H.; Reinders, M.J.; et al. Timing and localization of human dystrophin isoform expression provide insights into the cognitive phenotype of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doorenweerd, N.; Straathof, C.S.; Dumas, E.M.; Spitali, P.; Ginjaar, I.B.; Wokke, B.H.; Schrans, D.G.; van den Bergen, J.C.; van Zwet, E.W.; Webb, A.; et al. Reduced cerebral gray matter and altered white matter in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 76, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preethish-Kumar, V.; Shah, A.; Polavarapu, K.; Kumar, M.; Safai, A.; Vengalil, S.; Nashi, S.; Deepha, S.; Govindaraj, P.; Afsar, M.; et al. Disrupted structural connectome and neurocognitive functions in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Classifying and subtyping based on Dp140 dystrophin isoform. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 2113–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenggi, T.; Soontornmalai, A.; Schaub, M.C.; Fritschy, J.M. The role of utrophin and Dp71 for assembly of different dystrophin-associated protein complexes (DPCs) in the choroid plexus and microvasculature of the brain. Neuroscience 2004, 129, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, F.; Angeard, N.; Demerre, B.; Martie, I.; Benyaou, R.; Leturcq, F.; Cossee, M.; Deburgrave, N.; Saillour, Y.; Tuffery, S.; et al. Analysis of Dp71 contribution in the severity of mental retardation through comparison of Duchenne and Becker patients differing by mutation consequences on Dp71 expression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 3779–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, N.C.; Adams, M.E.; Froehner, S.C.; Kofuji, P. The potassium channel Kir4.1 associates with the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex via alpha-syntrophin in glia. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 28387–28392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, R.G.; Schipper, S.; Hoogland, G.; Schijns, O.E.; Dings, J.T.; Aalbers, M.W.; Vles, J.S. Dystrophin Distribution and Expression in Human and Experimental Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2016, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogland, G.; Hendriksen, R.G.; Slegers, R.J.; Hendriks, M.P.; Schijns, O.E.; Aalbers, M.W.; Vles, J.S. The expression of the distal dystrophin isoforms Dp140 and Dp71 in the human epileptic hippocampus in relation to cognitive functioning. Hippocampus 2019, 29, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Morena, C.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Saz-Lara, A.; López-Gil, J.F.; Fernández-Bravo-Rodrigo, J.; Cavero-Redondo, I. Epileptic disorders in Becker and Duchenne muscular dystrophies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 3461–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogland, G.; Hendriksen, R.G.; Slegers, R.J.; Hendriks, M.P.; Schijns, O.E.; Aalbers, M.W.; Vles, J.S. Intellectual ability in the duchenne muscular dystrophy and dystrophin gene mutation location. Balkan J. Med. Genet. 2015, 17, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushby, K.M.; Appleton, R.; Anderson, L.V.; Welch, J.L.; Kelly, P.; Gardner-Medwin, D. Deletion status and intellectual impairment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 1995, 37, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, S.V.; Abbs, S.; Clark, S.; Manzur, A.; Heckmatt, J.Z.H.; Dubowitz, V.; Bobrow, M. Correlation of clinical and deletion data in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy, with special reference to mental ability. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1992, 2, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolmaleky, H.M.; Zhou, J.R.; Thiagalingam, S. Cataloging recent advances in epigenetic alterations in major mental disorders and autism. Epigenomics 2021, 13, 1231–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, D.; Goemans, N.; Takeda, S.; Mercuri, E.; Aartsma-Rus, A. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrouki, F.; Relizani, K.; Bizot, F.; Tensorer, T.; Garcia, L.; Vaillend, C.; Goyenvalle, A. Partial Restoration of Brain Dystrophin and Behavioral Deficits by Exon Skipping in the Muscular Dystrophy X-Linked (mdx) Mouse. Ann. Neurol. 2022, 92, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoudi, A.; Barberat, S.; Le Coz, O.; Vacca, O.; Caquant, M.D.; Tensorer, T.; Sliwinski, E.; Garcia, L.; Muntoni, F.; Vaillend, C.; et al. Partial restoration of brain dystrophin by tricyclo-DNA antisense oligonucleotides alleviates emotional deficits in mdx52 mice. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 32, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Kuniishi, H.; Sakai, K.; Fukushima, Y.; Du, X.; Yamashiro, K.; Hori, K.; Imamura, M.; Hoshino, M.; Yamada, M.; et al. Brain Dp140 alters glutamatergic transmission and social behaviour in the mdx52 mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, 216, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyenvalle, A.; Griffith, G.; Babbs, A.; Andaloussi, S.E.; Ezzat, K.; Avril, A.; Dugovic, B.; Chaussenot, R.; Ferry, A.; Voit, T.; et al. Functional correction in mouse models of muscular dystrophy using exon-skipping tricyclo-DNA oligomers. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relizani, K.; Griffith, G.; Echevarría, L.; Zarrouki, F.; Facchinetti, P.; Vaillend, C.; Leumann, C.; Garcia, L.; Goyenvalle, A. Efficacy and Safety Profile of Tricyclo-DNA Antisense Oligonucleotides in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Mouse Model. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2017, 8, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barbarii, T.; Tudorache, R.A.; Craiu, D.; Neagu, E.; Brinduse, L.A.; Burloiu, C.M.; Iliescu, C.M.; Budisteanu, M.; Minciu, I.; Barca, D.G.; et al. Brain Matters in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: DMD Mutation Sites and Their Association with Neurological Comorbidities Through Isoform Impairment. Genes 2026, 17, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010012

Barbarii T, Tudorache RA, Craiu D, Neagu E, Brinduse LA, Burloiu CM, Iliescu CM, Budisteanu M, Minciu I, Barca DG, et al. Brain Matters in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: DMD Mutation Sites and Their Association with Neurological Comorbidities Through Isoform Impairment. Genes. 2026; 17(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbarii, Teodora, Raluca Anca Tudorache, Dana Craiu, Elena Neagu, Lacramioara Aurelia Brinduse, Carmen Magdalena Burloiu, Catrinel Mihaela Iliescu, Magdalena Budisteanu, Ioana Minciu, Diana Gabriela Barca, and et al. 2026. "Brain Matters in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: DMD Mutation Sites and Their Association with Neurological Comorbidities Through Isoform Impairment" Genes 17, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010012

APA StyleBarbarii, T., Tudorache, R. A., Craiu, D., Neagu, E., Brinduse, L. A., Burloiu, C. M., Iliescu, C. M., Budisteanu, M., Minciu, I., Barca, D. G., Sandu, C., Tarta-Arsene, O., Pomeran, C., Motoescu, C., Dica, A., Anghelescu, C., Surlica, D., Toma, A. I., & Butoianu, N. (2026). Brain Matters in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: DMD Mutation Sites and Their Association with Neurological Comorbidities Through Isoform Impairment. Genes, 17(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010012