Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Insights into the Hepatic Response to Dietary Carvacrol in Pengze Crucian Carp (Carassius auratus var. Pengze)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Husbandry

2.2. Experimental Design and Sampling

2.3. Cytokine Levels and Antioxidant Capacity

2.4. Transcriptomic Analysis

2.4.1. RNA Extraction

2.4.2. Library Preparation for Transcriptome Sequencing

2.4.3. Clustering and Sequencing

2.4.4. Data Processing

2.4.5. RT-qPCR Validations of RNA-Seq Data

2.5. Metabolome Analysis

2.5.1. Sample Preparation and Extraction

2.5.2. HPLC Conditions

2.5.3. MS Conditions (AB)

2.5.4. Analysis of LC-MS Data

3. Results

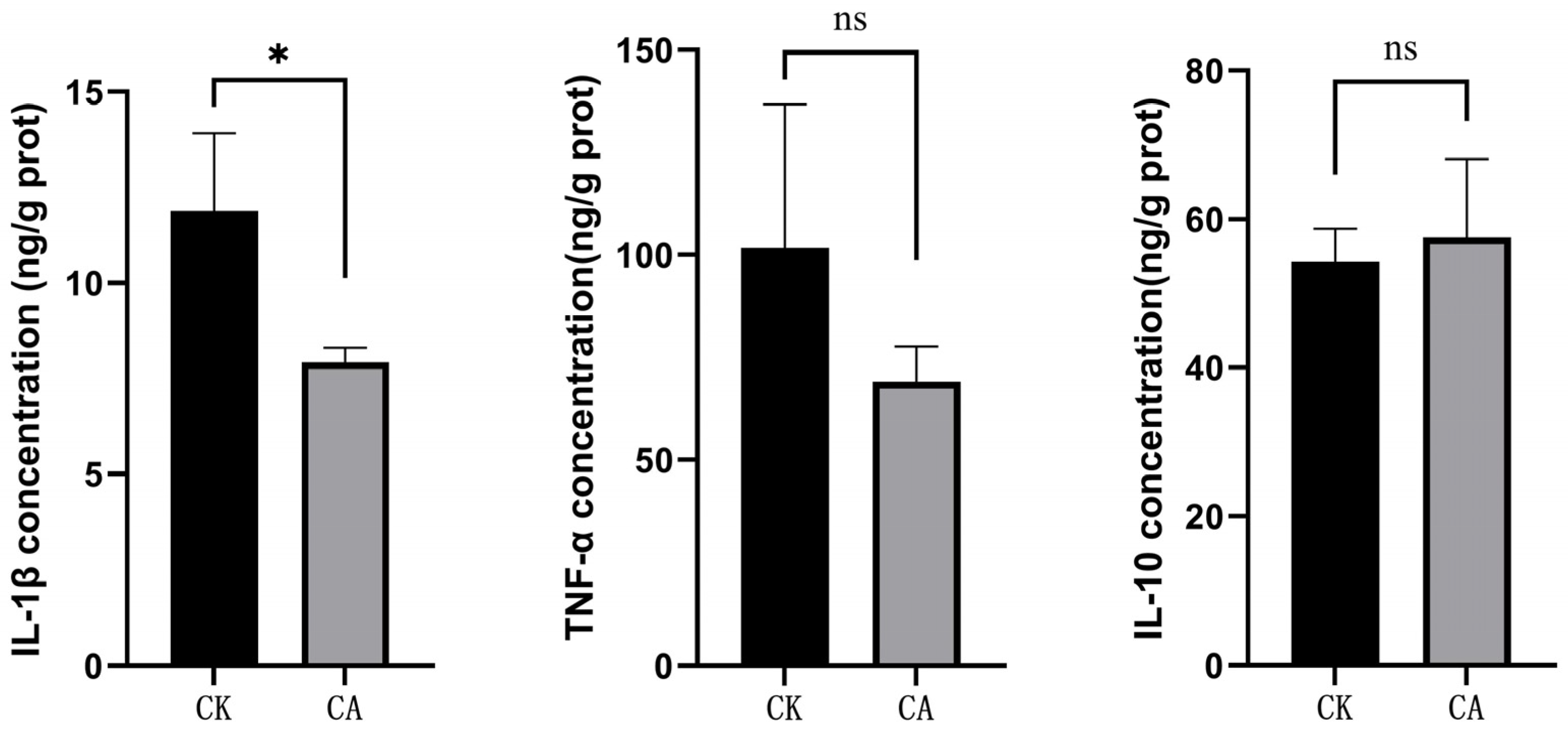

3.1. Changes of Cytokine Levels and Antioxidant Capacity

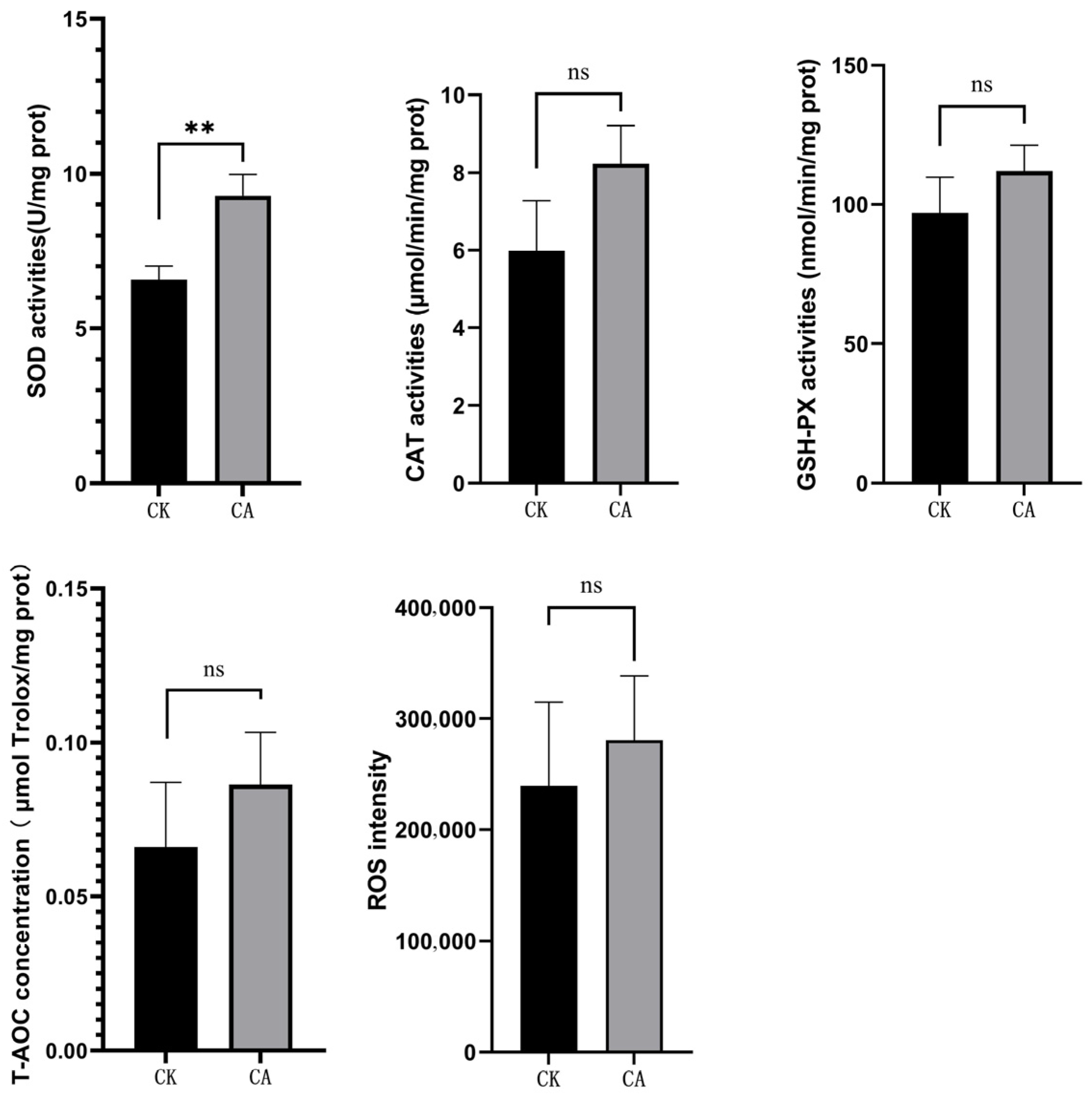

3.2. Transcriptome Changes

3.2.1. Transcriptome Sequence Assembly

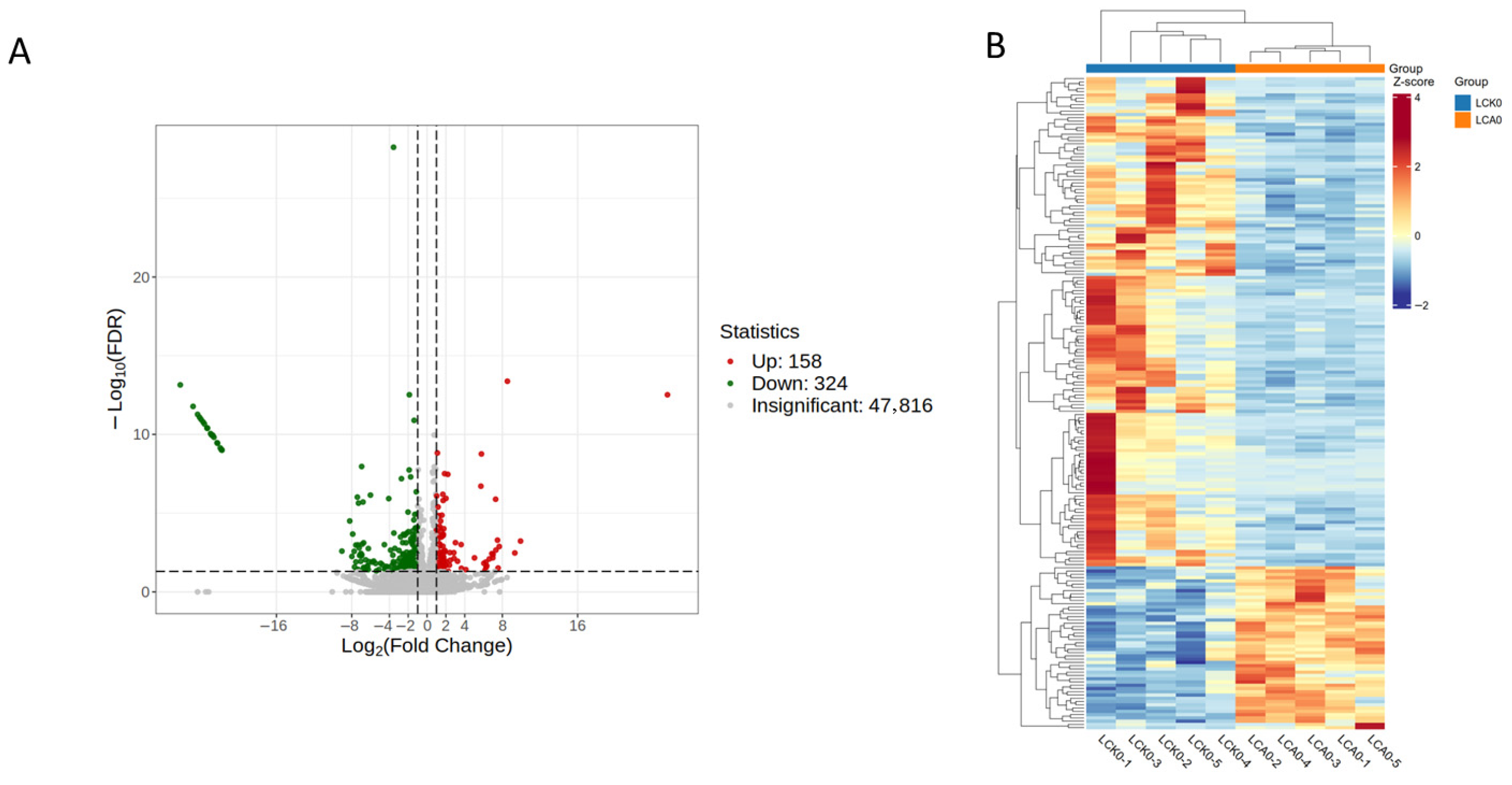

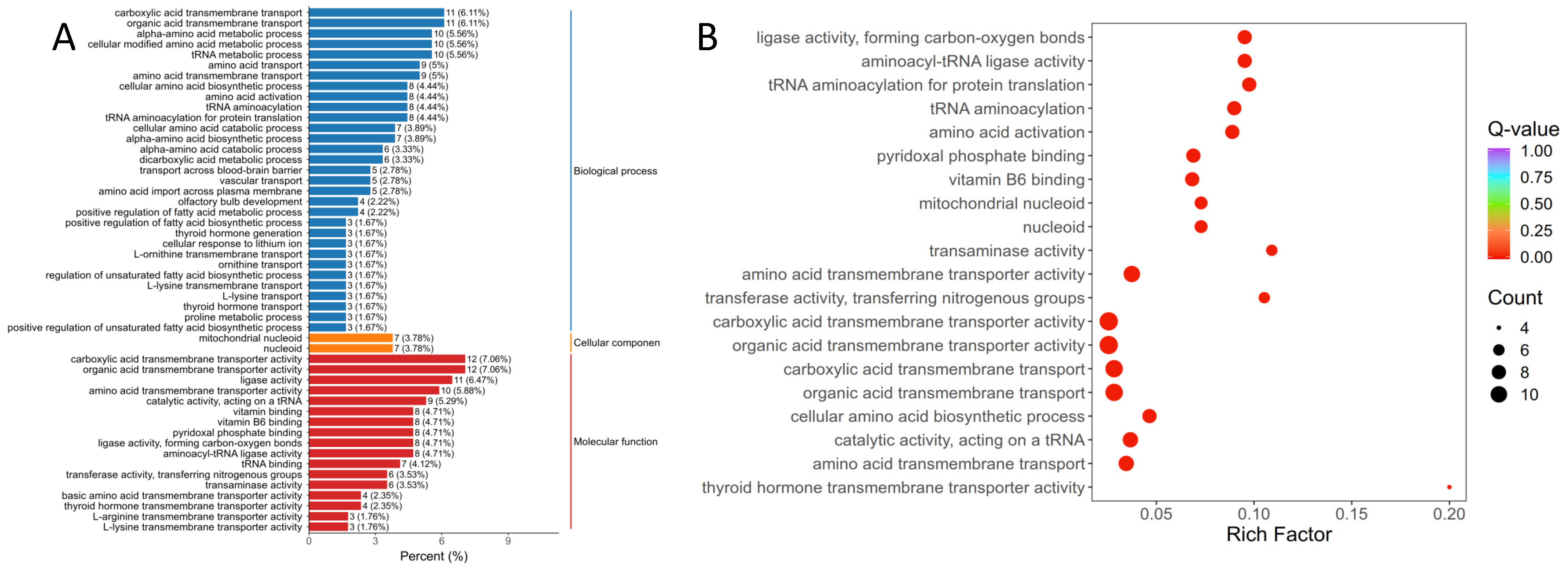

3.2.2. Annotation and Function Analysis

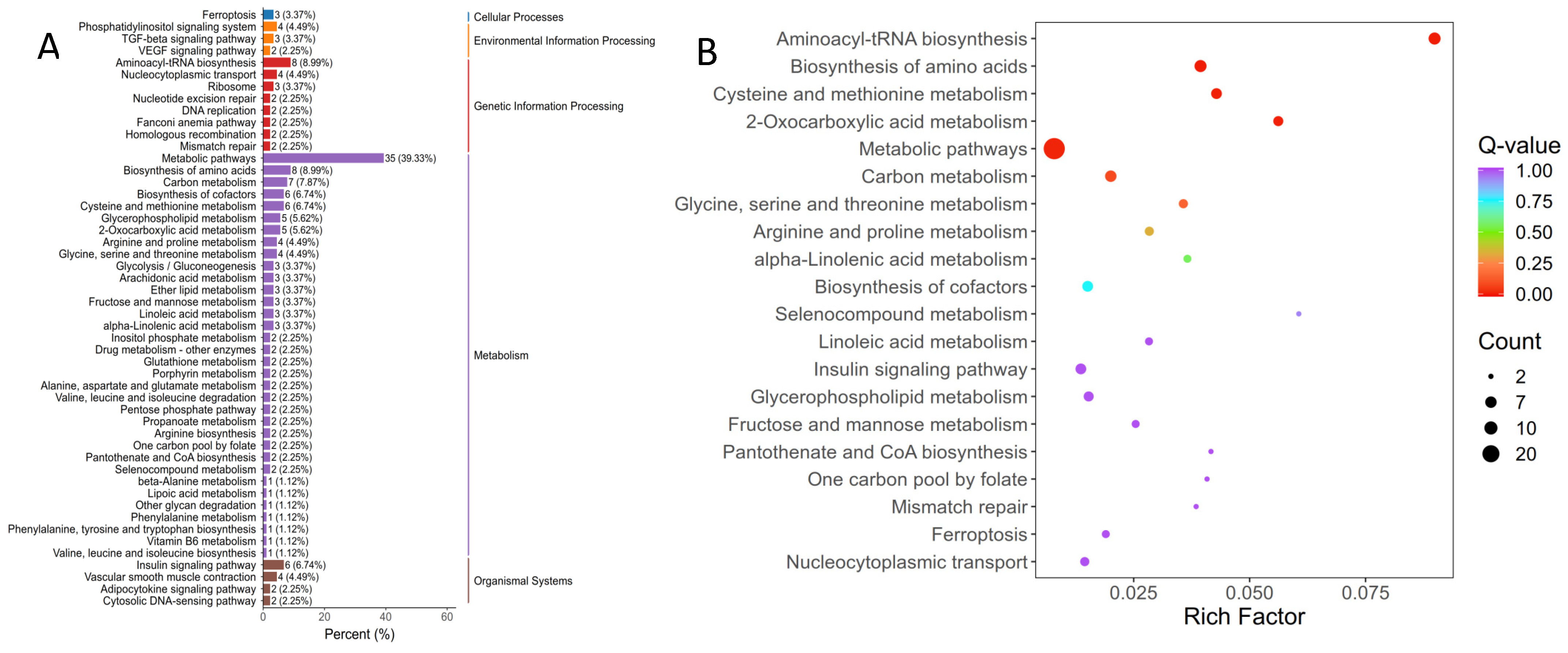

3.2.3. Changes in Gene Expression

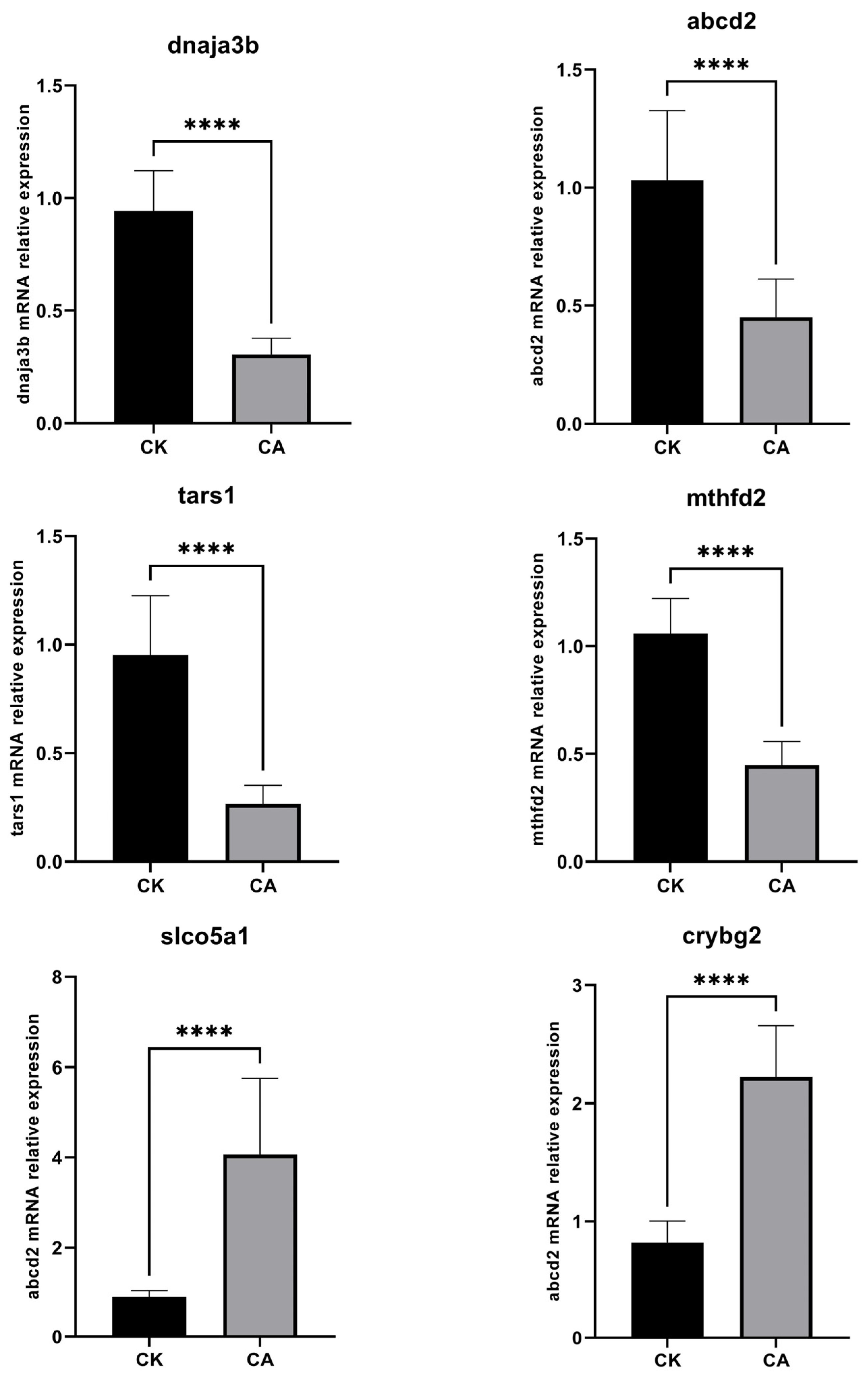

3.2.4. Expression Level of Validated Genes

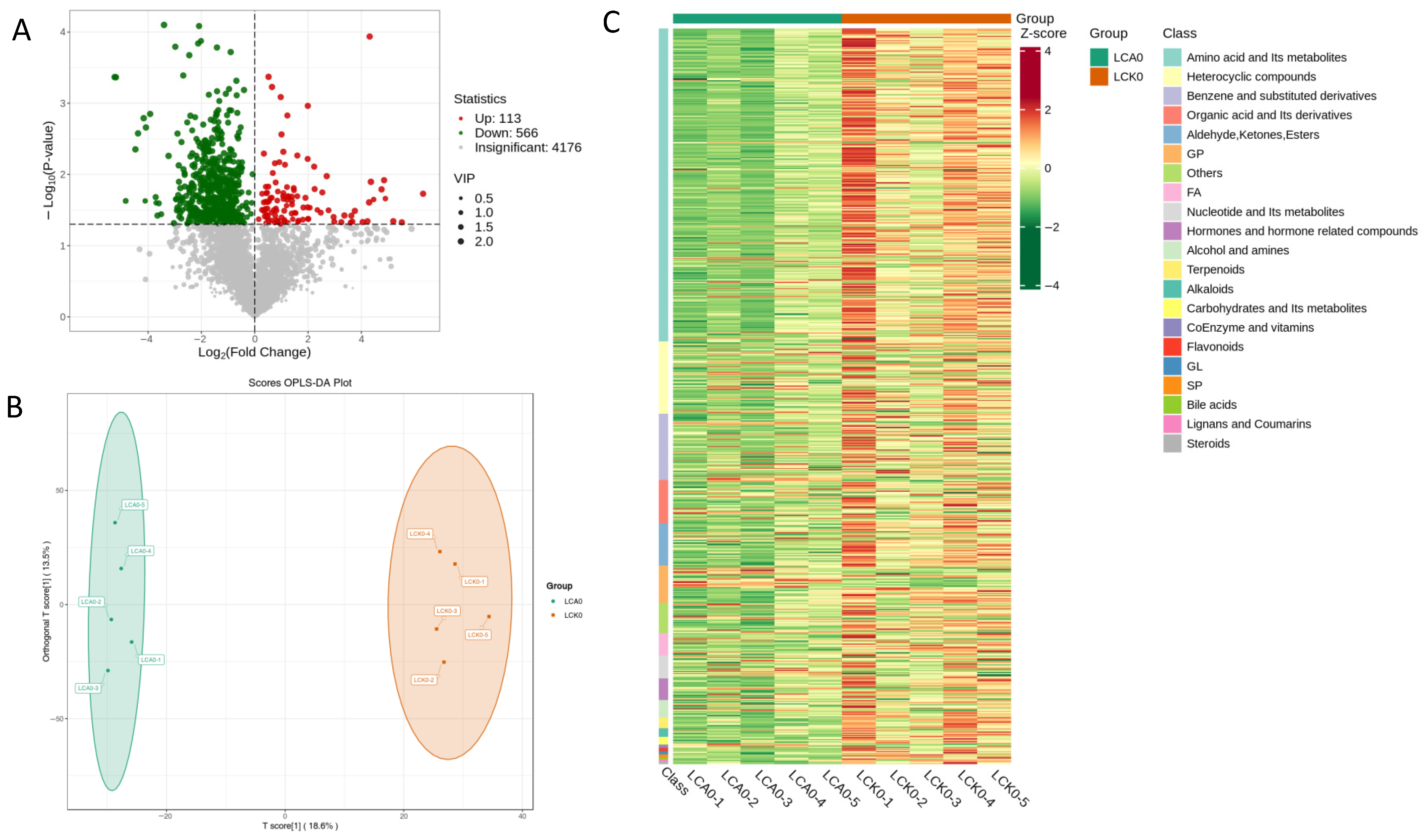

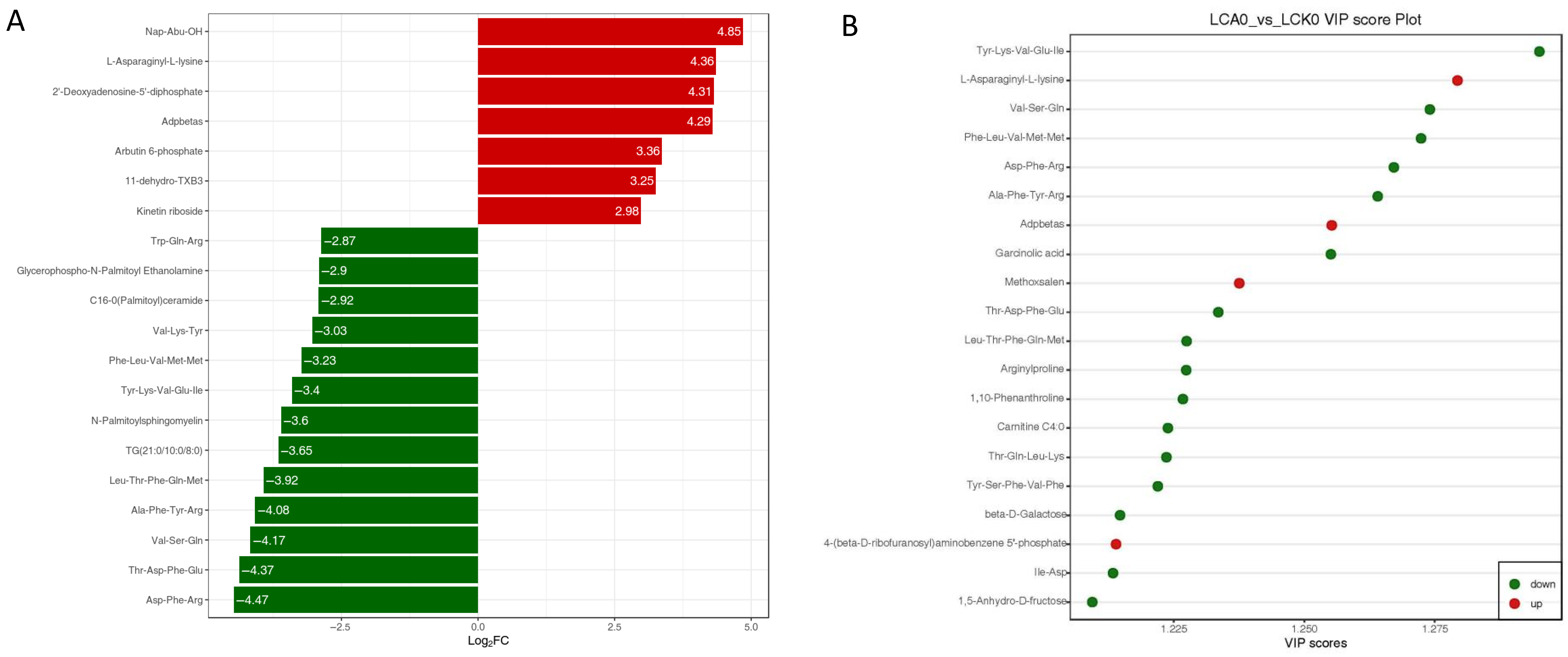

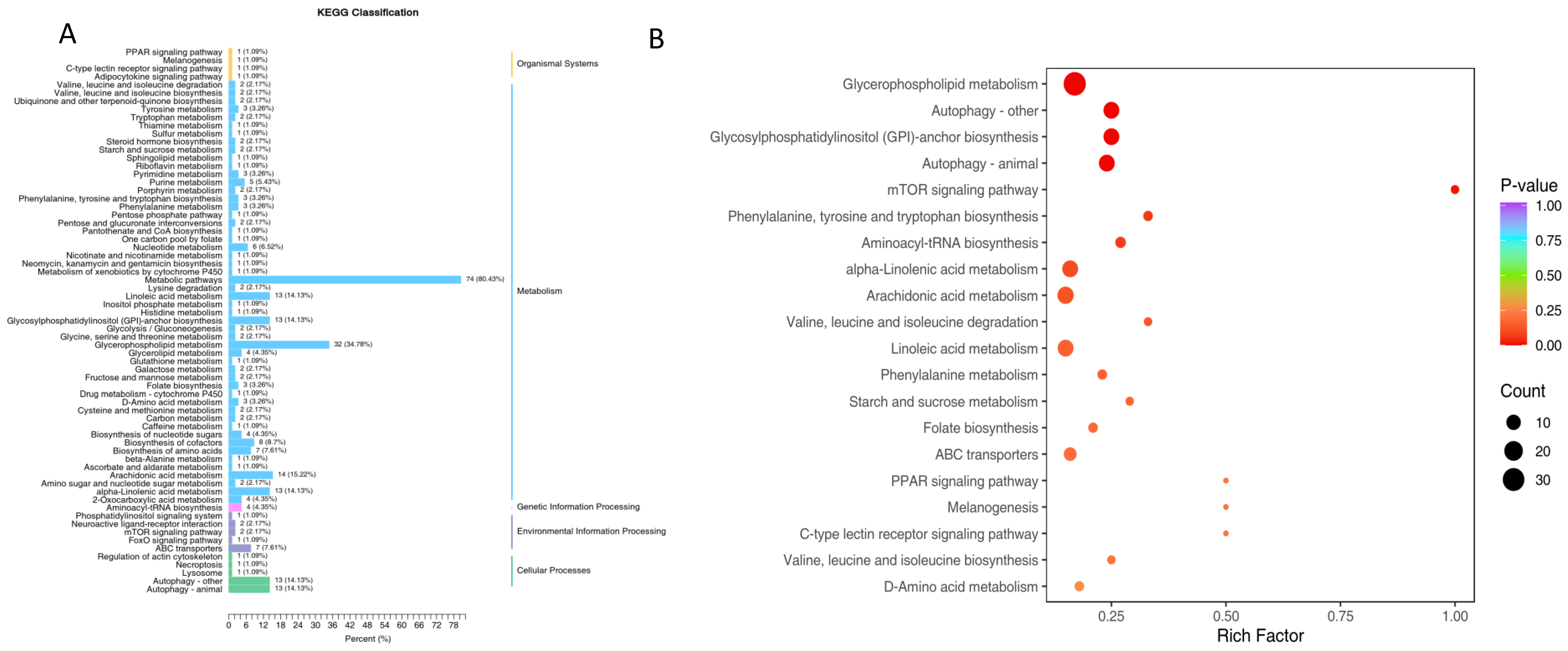

3.3. Changes of Metabolic Profiles

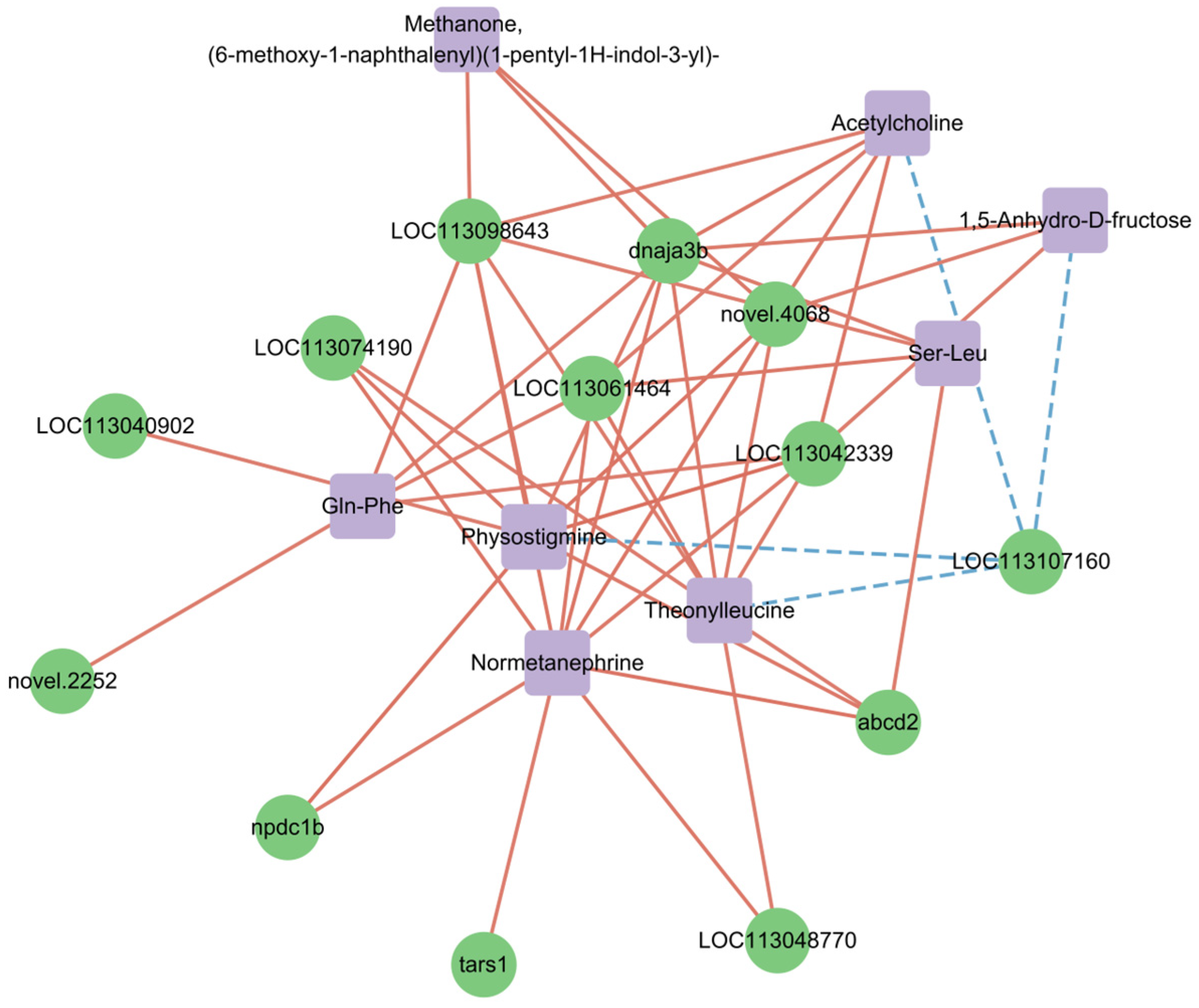

3.4. Conjoint Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ancillotti, M.; Eriksson, S.; Andersson, D.I.; Godskesen, T.; Fahlquist, J.N.; Veldwijk, J. Preferences regarding antibiotic treatment and the role of antibiotic resistance: A discrete choice experiment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limbu, S.M.; Chen, L.Q.; Zhang, M.L.; Du, Z.Y. A global analysis on the systemic effects of antibiotics in cultured fish and their potential human health risk: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 1015–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbee, C.R.; Green, R.; Matsumoto, M. Antibiotics in animal feeds: Risks and costs. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1985, 67, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.D. Antibiotic use in animal feed and its impact on human health. J. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2000, 13, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Hong, Y.K.; Yang, J.E.; Kwon, O.K.; Kim, S.C. Bioaccumulation and mass balance analysis of veterinary antibiotics in an agricultural environment. Toxics 2022, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, L.; Tanunchai, B.; Glaser, B. Antibiotics residues in pig slurry and manure and its environmental contamination potential. A Meta-analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marutescu, L.G.; Jaga, M.; Postolache, C.; Barbuceanu, F.; Milita, N.M.; Romascu, L.M.; Schmitt, H.; Roda Husman, A.M.; Sefeedpari, P.; Glaeser, S.; et al. Insights into the impact of manure on the environmental antibiotic residues and resistance pool. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 965132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, D.M. The EU precautionary bans of animal feed additive antibiotics. Toxicol. Lett. 2002, 128, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.J.; Jensen, H.H.; Backstrom, L.; Fabiosa, J. Economic impact of a ban on the use of over the counter antibiotics in US swine rations. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2001, 4, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.Q.; Li, C.; Zhao, M.Y.; Wang, H.N.; Tang, Y.Z. Withdrawal of antibiotic growth promoters in China and its impact on the foodborne pathogen Campylobacter coli of swine origin. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1004725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; El Zowalaty, M.E.; Lundkvist, Å.; Järhult, J.D.; Nayem, M.R.K.; Tanzin, A.Z.; Badsha, M.R.; Khan, S.A.; Ashour, H.M. Residual antimicrobial agents in food originating from animals. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.F.; Zhu, Y.L.; Abdel-Samie, M.A.; Li, C.Z.; Cui, H.Y.; Lin, L. Biological properties of essential oil emphasized on the feasibility as antibiotic substitute in feedstuff. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2023, 6, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhou, S.Y.D.; Jin, M.K.; Lu, T.; Cui, L.; Qian, H.F. Macleaya cordata extract, an antibiotic alternative, does not contribute to antibiotic resistance gene dissemination. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Liu, C.J.; Xue, Z. Application of immunostimulants in aquaculture: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Aquac. Res. 2017, 48, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Qin, T.; Chen, K.; Pan, L.K.; Xie, J.; Xi, B.W. Antimicrobial and antivirulence activities of carvacrol against pathogenic Aeromonas hydrophila. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novriadi, R.; Malahayati, S.; Kuan, S. Supplementation effect of dietary carvacrol and thymol polyphenols from Oregano Origanum vulgare on growth performance and health condition of pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Asian J. Fish. Aquat. Res. 2023, 24, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magouz, F.I.; Amer, A.A.; Faisal, A.; Sewilam, H.; Aboelenin, S.M.; Dawood, M.A. The effects of dietary oregano essential oil on the growth performance, intestinal health, immune, and antioxidative responses of Nile tilapia under acute heat stress. Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frota, R.; Gallani, S.U.; dos Santos, P.D.P.; de Souza Pereira, C.; Oishi, C.A.; Gonçalves, L.U.; Valladão, G.M.R. Effects of thymol: Carvacrol association on health and zootechnical performance of tambaqui Colossoma macropomum. Bol. Inst. Pesca 2022, 48, e725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafarifarsani, H.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Javahery, S.; Van Doan, H. Effects of dietary vitamin C, thyme essential oil, and quercetin on the immunological and antioxidant status of common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Aquaculture 2022, 553, 738053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.S.; Guo, X.Z.; Chen, Y.L.; Tang, Y.Q.; Xiao, H.H.; Li, S.M. Carvacrol promotes intestinal health in Pengze crucian carp, enhancing resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 17, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Liu, H.; Yan, X.; Huang, W.; Pan, S.; Zhou, M.; Lu, B.Q.; Tan, B.P.; Dong, X.H.; Yang, Y. Effect of dietary oregano oil on growth performance, disease resistance, intestinal morphology, immunity, and microbiota of hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂). Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1038394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.D.; Paz, A.D.L.; Val, A.L. Effect of carvacrol on the haemato--immunological parameters, growth and resistance of Colossoma macropomum (Characiformes: Serrasalmidae) infected by Aeromonas hydrophila. Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 3291–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboub, H.H.; Tartor, Y.H. Carvacrol essential oil stimulates growth performance, immune response, and tolerance of Nile tilapia to Cryptococcus uniguttulatus infection. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2020, 141, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.W.; Harmon, C.; O’Farrelly, C. Liver immunology and its role in inflammation and homeostasis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.Y.; Liu, C.H.; Lei, M.; Zeng, Q.M.; Li, L.; Tang, H.; Zhang, N.N. Metabolic regulation of the immune system in health and diseases: Mechanisms and interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülşafak, İ.; Küçükgül, A.; Küçükgül, A. Bio-functions of carvacrol-supplemented feeds on lipopolysaccharide-induced rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum, 1792). Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 2019, 18, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Aslam, M.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Saeed, F.; Ahmad, I.; Afzaal, M.; Arshad, M.U.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; El-Ghorab, A.H.; Khames, A.; et al. Therapeutic application of carvacrol: A comprehensive review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 3544–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruslé, J.; I Anadon, G.G. The structure and function of fish liver. In Fish Morphology; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, L.D.; Kang, K.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.G.; Zhao, H.F.; Sun, X.Y.; Tong, L.Q.; Zhang, F. Carvacrol alleviates ischemia reperfusion injury by regulating the PI3K-Akt pathway in rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrah, S.; Ozcicek, F.; Gundogdu, B.; Cicek, B.; Coban, T.A.; Suleyman, B.; Altuner, D.; Bulut, S.; Suleyman, H. Carvacrol prevents acrylamide-induced oxidative and inflammatory liver damage and dysfunction in rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1161448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GÜMÜŞ, R.; Erol, H.S.; Imik, H.; Halici, M. The effects of the supplementation of lamb rations with oregano essential oil on the performance, some blood parameters and antioxidant metabolism in meat and liver tissues. Kafkas Üniv. Vet. Fak. 2017, 23, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.Y.; Wu, L.J.; Yuan, S.Y.; Liu, G.F.; Wang, Y.L.; Fang, L.; Xu, D.J. Carvacrol alleviates liver fibrosis by inhibiting TRPM7 and modulating the MAPK signaling pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 898, 173982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajagai, Y.S.; Radovanovic, A.; Steel, J.C.; Stanley, D. The Effects of continual consumption of Origanum vulgare on liver transcriptomics. Animals 2021, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabino, M.; Capomaccio, S.; Cappelli, K.; Verini-Supplizi, A.; Bomba, L.; Ajmone-Marsan, P.; Cobellis, G.; Olivieri, O.; Pieramati, C.; Trabalza-Marinucci, M. Oregano dietary supplementation modifies the liver transcriptome profile in broilers: RNASeq analysis. Res. Veter. Sci. 2018, 117, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Coz, J.; Ilic, S.; Fibi-Smetana, S.; Schatzmayr, G.; Zaunschirm, M.; Grenier, B. Exploring with transcriptomic approaches the underlying mechanisms of an essential oil-based phytogenic in the small intestine and liver of pigs. Front. Veter. Sci. 2021, 8, 650732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.J.; Zhao, C.Y.; Kuan, K.C.S.; Cao, X.Y.; Wang, B.W.; Ren, Y.C. Effects of dietary oregano essential oil-mediated intestinal microbiota and transcription on amino acid metabolism and Aeromonas salmonicida resistance in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 1835–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarghandian, S.; Farkhondeh, T.; Samini, F.; Borji, A. Protective effects of carvacrol against oxidative stress induced by chronic stress in rat’s brain, liver, and kidney. Biochem. Res. Int. 2016, 1, 2645237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarghandian, S.; Azimi-Nezhad, M.; Farkhondeh, T. Preventive effect of carvacrol against oxidative damage in aged rat liver. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2017, 87, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalletta, S.; Flati, V.; Toniato, E.; Di Gregorio, J.; Marino, A.; Pierdomenico, L.; Marchisio, M.; D’Orazi, G.; Cacciatore, I.; Robuffo, I. Carvacrol reduces adipogenic differentiation by modulating autophagy and ChREBP expression. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J.K.; Rao, M.S. Lipid metabolism and liver inflammation. II. Fatty liver disease and fatty acid oxidation. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2006, 290, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristatile, B.; Al–Assafa, A.H.; Pugalendi, K.V. Carvacrol ameliorates the PPAR-α and cytochrome P450 expression on d-galactosamine induced hepatotoxicity rats. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 11, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, J.; Zhou, H.; Chen, L.; Zhao, W.; Wu, Q.; Li, S.S. Effect and mechanism of carvacrol on liver injury in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chin. Arch. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2024, 42, 131–135+280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, B.; De-Medina, T.; Syken, J.; Vidal, M.; Münger, K. A novel human DnaJ protein, hTid-1, a homolog of the Drosophila tumor suppressor protein Tid56, can interact with the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. Virology 1998, 247, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.B.; Shao, Y.M.; Miao, S.; Wang, L. The diversity of the DnaJ/Hsp40 family, the crucial partners for Hsp70 chaperones. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 2560–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traicoff, J.; Hewitt, S.M.; Chung, J.Y. DNAJA3 (DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 3). Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. 2012, 16, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.J.; Qiao, Y.J.; Qu, J.B.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Wang, X.B. The hsp40 gene family in Japanese flounder: Identification, phylogenetic relationships, molecular evolution analysis, and expression patterns. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 7, 596534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.Y.; Hsu, J.Y.; Lin, C.H.; Kuo, Y.C.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, H.Y.; Liu, S.J.; Chien, K.L. Association of stress hormones and the risk of cardiovascular diseases systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev. 2024, 23, 200305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangle, Y.; Bamel, K.; Purty, R.S. Role of acetylcholine and acetylcholinesterase in improving abiotic stress resistance/tolerance. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2024, 17, 2353200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimble, G.K. The significance of peptides in clinical nutrition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1994, 14, 419–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, B.F.; Li, J.; Guo, Q.L.; Zhang, M.; Pei, Z.Y.; Hu, Y. Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of novel ferrocenyl (piperazine-1-yl) methanone-based derivatives. Med. Chem. 2023, 19, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohanka, M. Pharmacological influencing of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in Infectious diseases and inflammatory pathologies. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredient | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| CK | CA | |

| Fish meal | 14.00 | 14.00 |

| Soybean meal | 26.00 | 26.00 |

| Rapeseed meal | 23.00 | 23.00 |

| Corn grain | 22.00 | 22.00 |

| Soybean oil | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Fish oil | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Coated lysine | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Coated methionine | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Vitamin mixture a | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Mineral mixture b | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Choline | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| CaH2PO4 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| Vitamin C phosphate ester | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose sodium | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose | 6.15 | 5.55 |

| Microencapsulated Carvacrol | 0 | 0.60 |

| Chemical composition | ||

| Crude protein | 33.14 | 33.15 |

| Crude lipid | 4.82 | 4.81 |

| Crude ash | 5.75 | 5.76 |

| Moisture | 10.2 | 10.1 |

| Target Genes | Primers | Oligonucleotide (5′-3′) | References (NCBI Accession No.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | β-actin-F | CTGGTATCGTGATGGACTCT | XM_026258408.1 |

| β-actin-R | AGCTCATAGCTCTTCTCCAG | ||

| dnaja3b | dnaja3b-F | CAGTGTTTCGTCGTGATGGC | XM_026198116.1 |

| dnaja3b-R | GCCTGGAGGAATCGCAATGT | ||

| abcd2 | abcd2-F | AGATGCACATCAATGGCCCC | XM_026225352.1 |

| abcd2-R | CATCCCTTCCTCTACCTTGAAGT | ||

| tars1 | tars1-F | GCAAAGAGTGTCTGCTGAAATACC | XM_026211345.1 |

| tars1-R | GGAGGCCATAGCTTGGAAGAG | ||

| mthfd2 | mthfd2-F | CCCATGACCGTAGCCATGC | XM_026259937.1 |

| mthfd2-R | AGTGTGGAATGTGCAGGAGTTG | ||

| slco5a1 | slco5a1-F | GGATTCACCCACCAGGACAG | XM_026200927.1 |

| slco5a1-R | TCGGTTGGATTCAGTTCGCA | ||

| crybg2 | crybg2-F | GGGCTTTGCTGTGTCCCTAT | XM_026289848.1 |

| crybg2-R | TGACTCCTGGGCCTTCACTA |

| Sample | Raw Reads | Clean Reads | Clean Base (G) | Error Rate (%) | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) | GC Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCK0-1 | 45,791,696 | 42,845,296 | 6.43 | 0.02 | 98.51 | 95.51 | 47.05 |

| LCK0-2 | 49,500,992 | 47,827,558 | 7.17 | 0.02 | 98.41 | 95.16 | 46.88 |

| LCK0-3 | 46,497,432 | 45,024,468 | 6.75 | 0.02 | 98.50 | 95.39 | 47.00 |

| LCK0-4 | 46,874,742 | 45,749,482 | 6.86 | 0.02 | 98.35 | 95.00 | 46.04 |

| LCK0-5 | 46,562,158 | 45,104,346 | 6.77 | 0.03 | 97.93 | 93.93 | 46.68 |

| LCA0-1 | 58,359,686 | 56,624,310 | 8.49 | 0.02 | 98.51 | 95.37 | 47.66 |

| LCA0-2 | 46,806,092 | 45,612,338 | 6.84 | 0.02 | 98.47 | 95.31 | 46.37 |

| LCA0-3 | 54,030,206 | 52,353,992 | 7.85 | 0.02 | 98.46 | 95.29 | 47.11 |

| LCA0-4 | 49,461,430 | 47,833,286 | 7.17 | 0.02 | 98.45 | 95.26 | 46.85 |

| LCA0-5 | 47,379,162 | 45,757,524 | 6.86 | 0.02 | 98.57 | 95.56 | 46.82 |

| Sample | Total Read Pairs | Total Mapped Reads | Uniq Mapped Reads | Multiple Mapped Reads |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCK0-1 | 42,845,296 | 38,651,367 (90.21%) | 34,183,021 (79.78%) | 4,468,346 (10.43%) |

| LCK0-2 | 47,827,558 | 43,101,583 (90.12%) | 38,436,930 (80.37%) | 4,664,653 (9.75%) |

| LCK0-3 | 45,024,468 | 40,645,941 (90.28%) | 37,442,403 (83.16%) | 3,203,538 (7.12%) |

| LCK0-4 | 45,749,482 | 40,413,797 (88.34%) | 37,319,450 (81.57%) | 3,094,347 (6.76%) |

| LCK0-5 | 45,104,346 | 40,729,223 (90.30%) | 36,545,121 (81.02%) | 4,184,102 (9.28%) |

| LCA0-1 | 56,624,310 | 51,227,129 (90.47%) | 45,976,251 (81.20%) | 5,250,878 (9.27%) |

| LCA0-2 | 45,612,338 | 40,862,162 (89.59%) | 37,230,007 (81.62%) | 3,632,155 (7.96%) |

| LCA0-3 | 52,353,992 | 47,370,453 (90.48%) | 43,434,078 (82.96%) | 3,936,375 (7.52%) |

| LCA0-4 | 47,833,286 | 43,238,485 (90.39%) | 39,735,201 (83.07%) | 3,503,284 (7.32%) |

| LCA0-5 | 45,757,524 | 41,165,238 (89.96%) | 37,548,489 (82.06%) | 3,616,749 (7.90%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Lu, J.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, H. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Insights into the Hepatic Response to Dietary Carvacrol in Pengze Crucian Carp (Carassius auratus var. Pengze). Genes 2025, 16, 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121491

Liu W, Wang Y, Guo X, Lu J, Li L, Li S, Tang Y, Xiao H. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Insights into the Hepatic Response to Dietary Carvacrol in Pengze Crucian Carp (Carassius auratus var. Pengze). Genes. 2025; 16(12):1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121491

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Wenshu, Yuzhu Wang, Xiaoze Guo, Jingjing Lu, Lingya Li, Siming Li, Yanqiang Tang, and Haihong Xiao. 2025. "Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Insights into the Hepatic Response to Dietary Carvacrol in Pengze Crucian Carp (Carassius auratus var. Pengze)" Genes 16, no. 12: 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121491

APA StyleLiu, W., Wang, Y., Guo, X., Lu, J., Li, L., Li, S., Tang, Y., & Xiao, H. (2025). Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Insights into the Hepatic Response to Dietary Carvacrol in Pengze Crucian Carp (Carassius auratus var. Pengze). Genes, 16(12), 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121491