Genome-Wide Identification of the DFR Gene Family in Lonicera japonica Thunb. and Response to Drought and Salt Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Stress Treatments

2.2. Identification and Chromosomal Distribution of the LjDFR Gene Family

2.3. Cloning, Physicochemical Properties, and Structural Characteristic Analysis of LjDFR Genes

2.4. Subcellular Localization Analysis

2.5. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. Conserved Motif and Gene Structure Analysis

2.7. Collinearity Analysis and Identification of Cis-Acting Elements in Promoters of the LjDFR Gene Family

2.8. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and qRT-PCR Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification, Full-Length Cloning, and Chromosomal Distribution of the LjDFR Gene Family

3.2. Protein Physicochemical Properties and Structural Analysis of the LjDFR Gene Family

3.3. Subcellular Localization Analysis of LjDFR Proteins

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of the LjDFR Family

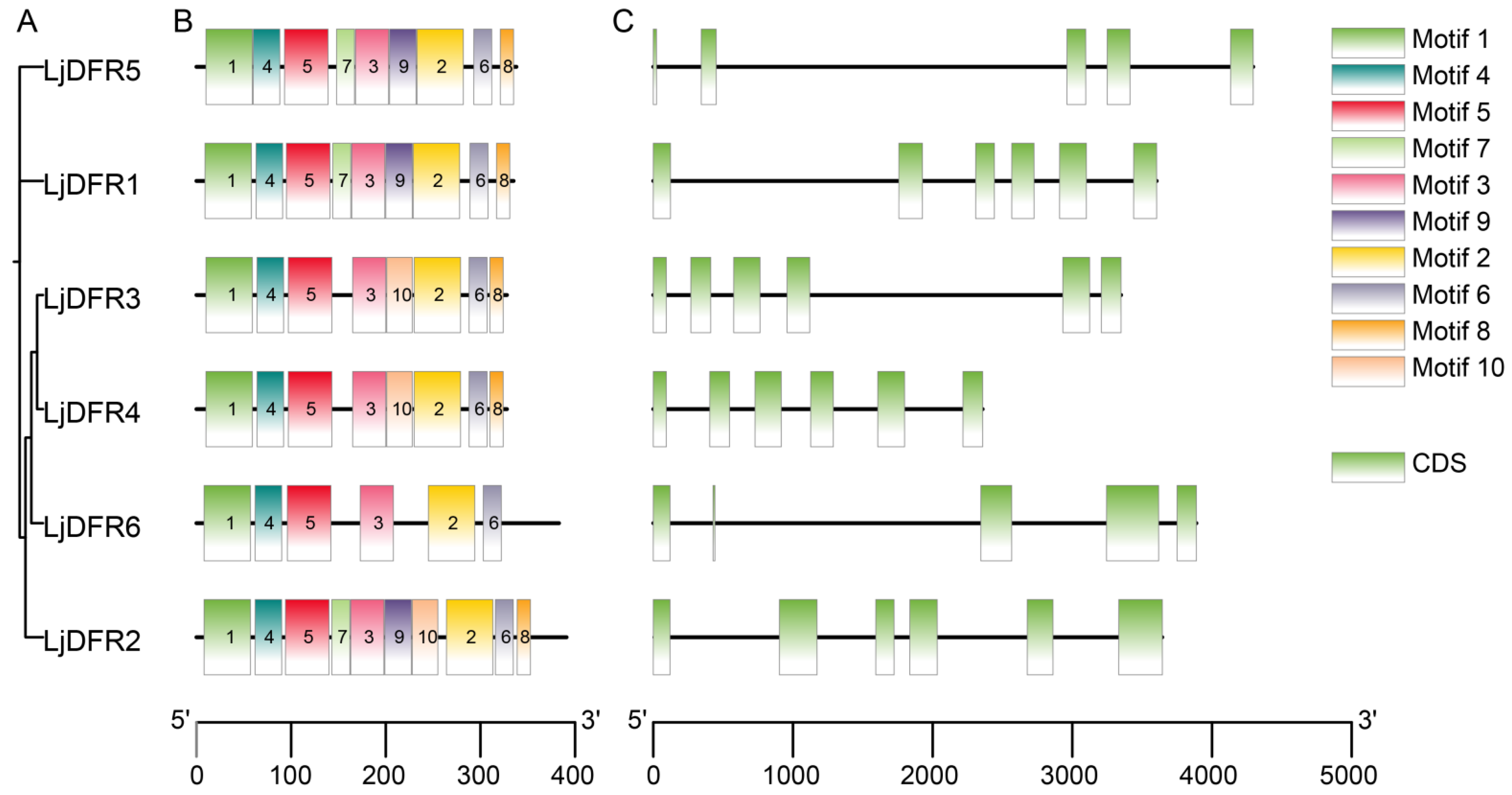

3.5. Gene Structure, Conserved Motifs, and Synteny Analysis of the LjDFR Gene Family

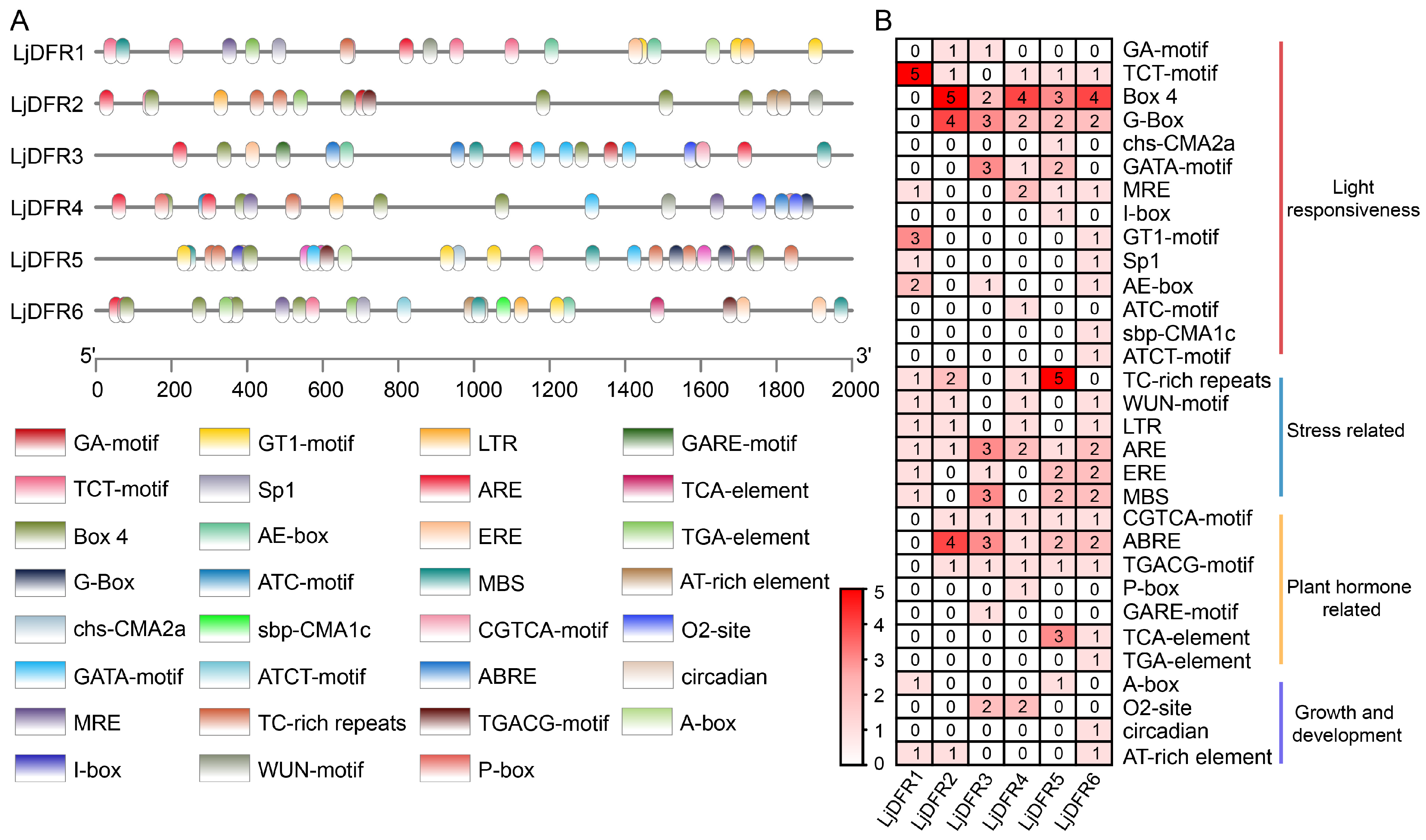

3.6. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in the Promoters of LjDFR Genes

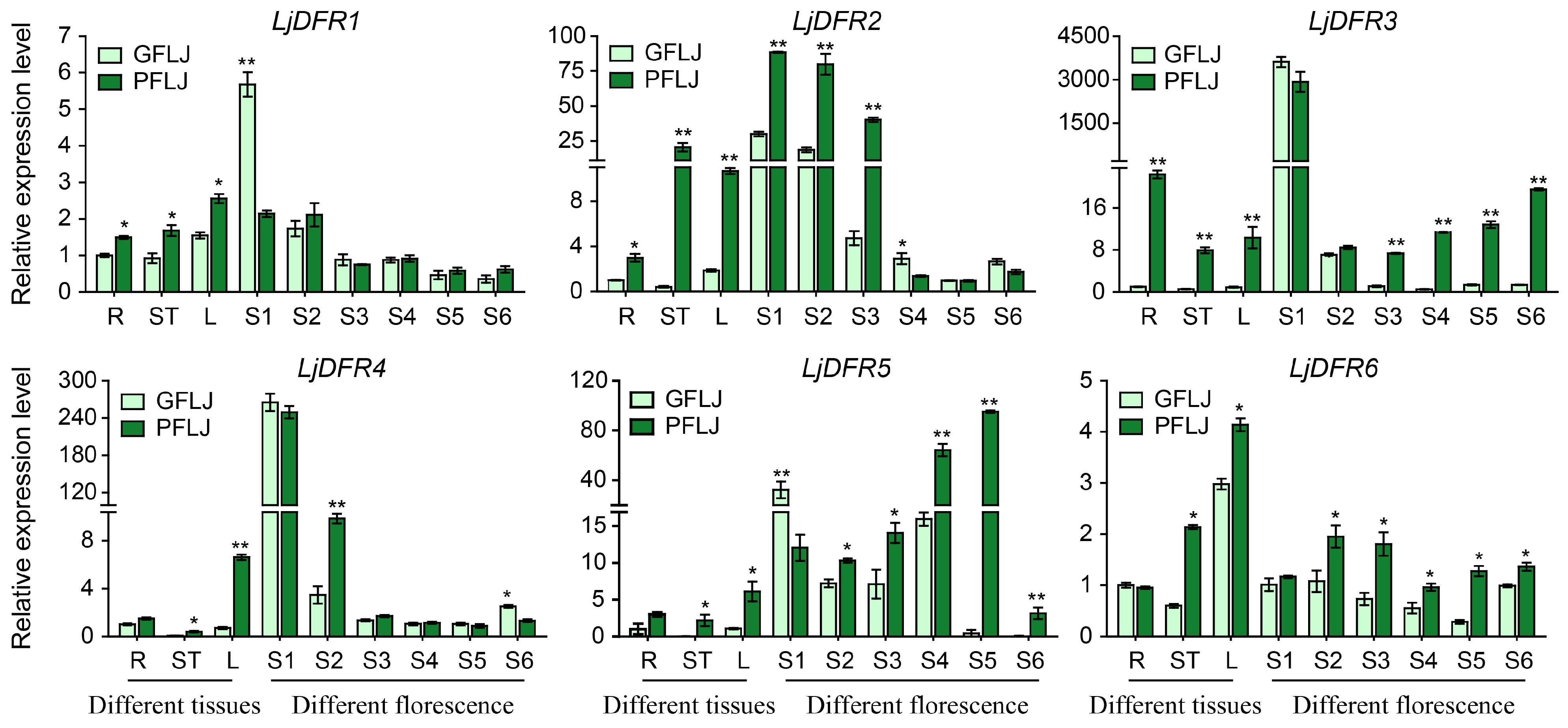

3.7. Tissue Expression Patterns of the LjDFR Gene Family

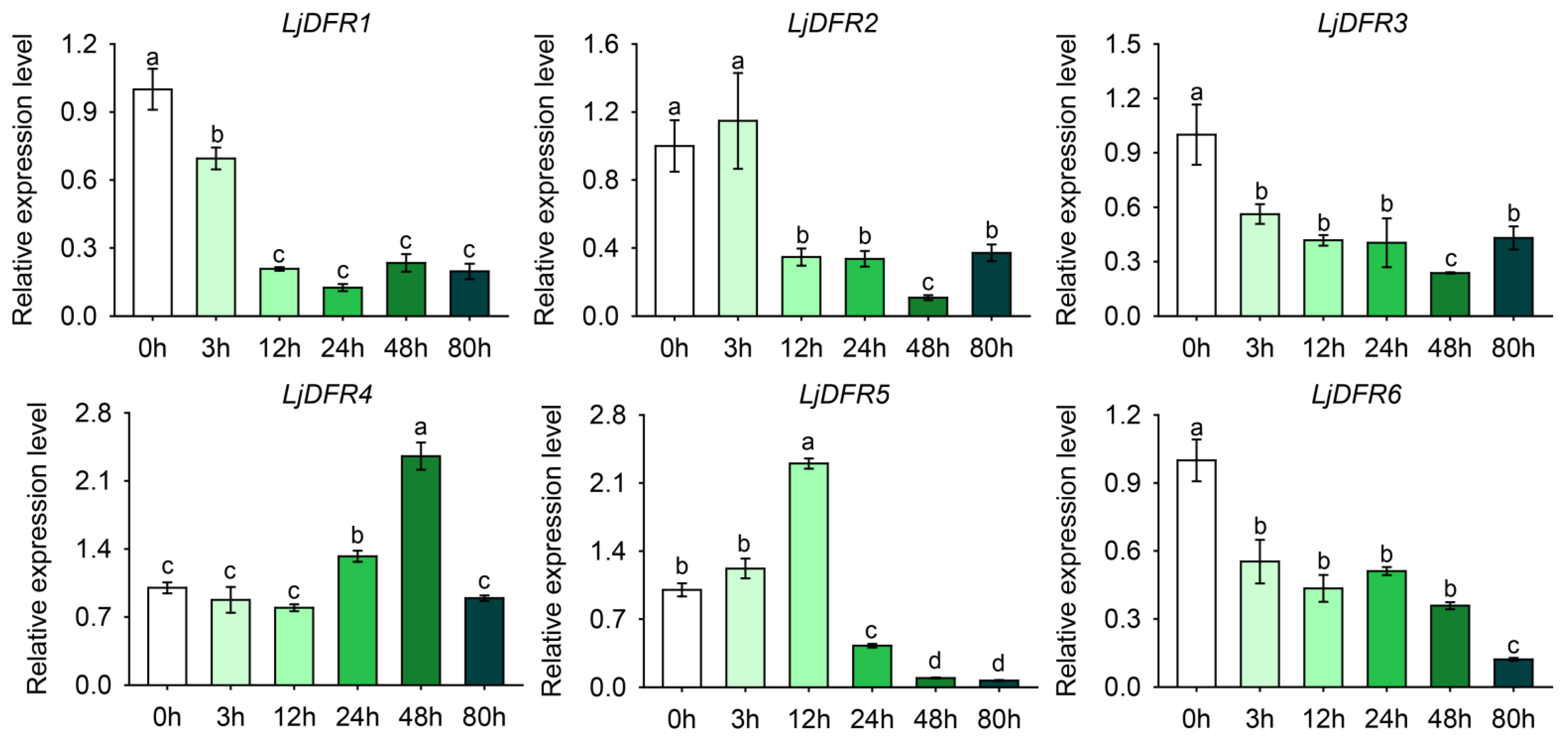

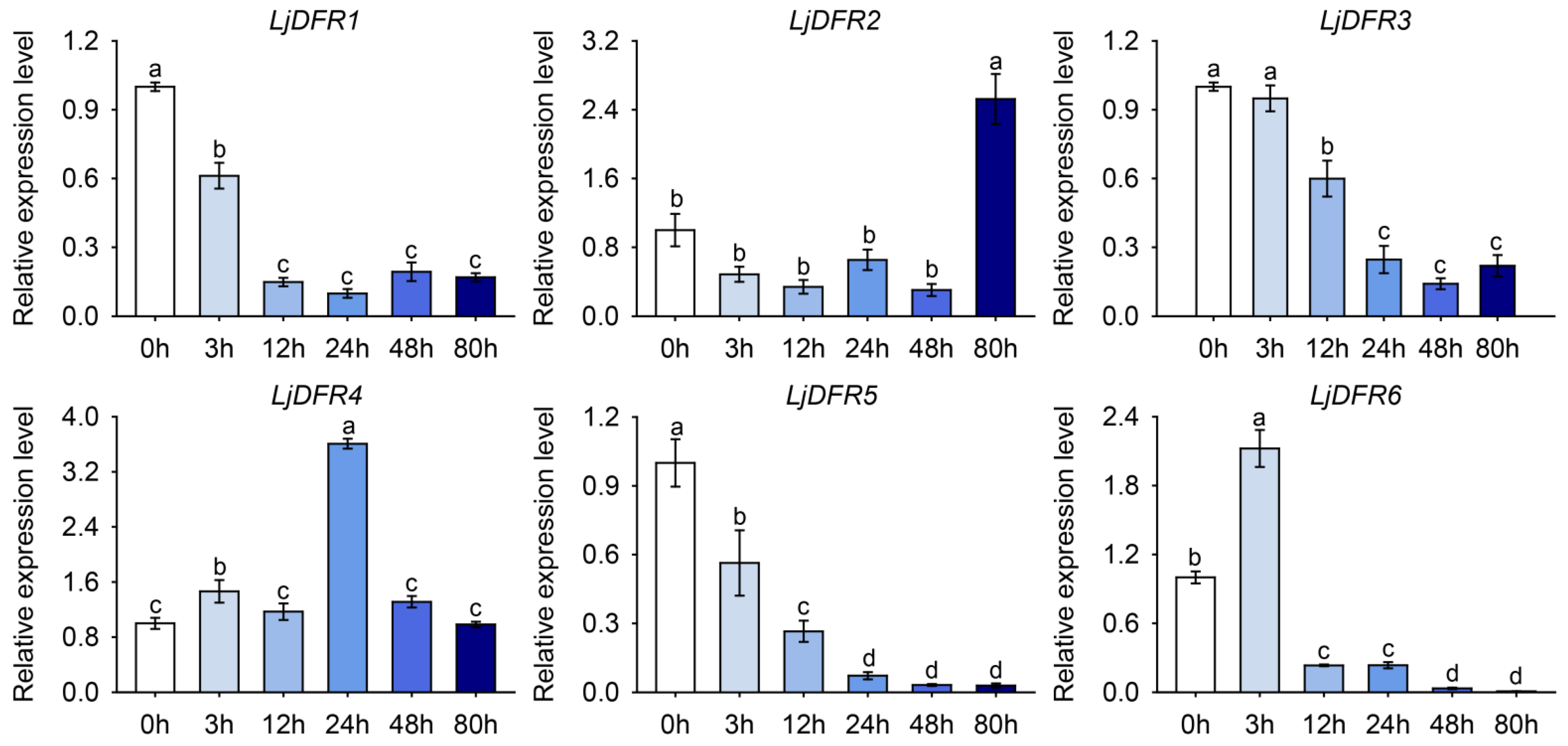

3.8. Expression Patterns of the LjDFR Gene Family Under Drought and Salt Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karanjalker, G.R.; Ravishankar, K.V.; Shivashankara, K.S.; Dinesh, M.R.; Roy, T.K.; Sudhakar Rao, D.V. A Study on the expression of genes involved in carotenoids and anthocyanins during ripening in fruit peel of green, yellow, and red colored mango cultivars. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 184, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Venail, J.; Mackay, S.; Bailey, P.C.; Schwinn, K.E.; Jameson, P.E.; Martin, C.R.; Davies, K.M. The molecular basis for venation patterning of pigmentation and its effect on pollinator attraction in flowers of Antirrhinum. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Butelli, E.; Martin, C. Engineering anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 19, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, Z.W.; Meng, J.F. Reduction of dihydrokaempferol by Vitis vinfera dihydroflavonol 4-reductase to produce orange Pelargonidin-Type anthocyanins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 3524–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaakola, L. New insights into the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in fruits. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFountain, A.M.; Yuan, Y.W. Repressors of anthocyanin biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, N.; Miyahara, T.; Okamoto, M.; Hirose, Y.; Sakaguchi, K.; Hatano, S.; Ozeki, Y. Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase activity is associated with the intensity of flower colors in delphinium. Plant Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Ruan, R.J.; Wang, L.J.; Jiang, Z.F.; Gu, X.J.; Chen, L.S.; Xu, M.J. Functional and correlation analyses of dihydroflavonol-4-reductase genes indicate their roles in regulating anthocyanin changes in Ginkgo biloba. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 152, 112546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.T.; Ryu, S.; Yi, H.; Shin, B.; Cheong, H.; Choi, G. Alteration of a single amino acid changes the substrate specificity of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase. Plant J. 2001, 25, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.L.; Lou, Q.; Ma, J.R.; Su, B.B.; Gao, Z.Z.; Liu, Y.L. Cloning and functional characterization of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase gene involved in anthocyanidin biosynthesis of Grape Hyacinth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, J.; Mattila1, S.; Abdou, S.M.; Sipari, N.; Teeri, T.H. Petunia dihydroflavonol 4-reductase is only a few amino acids away from producing orange pelargonidinbased anthocyanins. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1227219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, X.F.; Pan, H.; Li, M.X.; Miao, X.L.; Ding, H. Lonicera japonica Thunb.: Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important traditional Chinese medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 138, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, O.N.; Kim, G.S.; Park, S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, W.S.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, C.Y.; Jin, J.S.; Choi, S.K.; et al. Determination of polyphenol components of Lonicera japonica Thunb. using liquid chromatography—tandem mass spectrometry: Contribution to the overall antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, X.D.; Huang, L.Q.; Lin, S.F. Anthocyanins from buds of Lonicera japonica Thunb. var. chinensis (Wats.) Bak. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lian, X.; Ye, C.; Wang, L. Analysis of flower color variations at different developmental stages in two L. japonica (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) cultivars. HortScience 2019, 54, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, R.L.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.N. Identification and characterization of DFR gene family and cloning of candidate genes for anthocyanin biosynthesis in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.X.; Shi, X.X.; Gao, L.P.; Rashid, A.; Li, Y.; Lei, T.; Dai, X.L.; Xia, T.; Wang, Y.S. Functional analysis of the dihydroflavonol 4-reductase family of Camellia sinensis: Exploiting key amino acids to reconstruct reduction activity. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.C.D.; Nogueira, R.J.M.C.; Araújo, F.P.D.; Melo, N.F.D.; Neto, A.D.D.A. Physiological responses to salt stress in young umbu plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 63, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.D.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Gao, R.R.; Hao, L.J.; Hu, Y.T.; He, C.N.; Sun, W.; Xu, M.M.; Peters, R.J.; et al. The honeysuckle genome provides insight into the molecular mechanism of carotenoid metabolism underlying dynamic flower coloration. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 930–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.D.; Tan, Z.W.; Yu, Y.L.; Li, L.; Xu, L.J.; Yang, H.Q.; Yang, Q.; Dong, W.; An, S.F.; Liang, H.Z. Cloning, structure and expression profile analysis of CtANR2 and CtANR3 genes from Carthamus tinctorius L. Acta Agric. Boreali-Sin. 2023, 38, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.H.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Tang, H.B.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.P.; Wang, X.Y.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.Z.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Y.; Chen, L.; Qiao, Y.G.; Rong, Y.; Wang, J.S. Selection of reference genes by qRT-PCR inflower organ of Lonicera japonica Thunb. J Shanxi Agri Sci. 2017, 45, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P.; Heidmann, I.; Forkmann, G.; Saedler, H. A new Petunia flower colour generated by transformation of a mutant with a maize gene. Nature 1987, 330, 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, S.; Liu, Y.T.; Cui, B.Q.; Cheng, J.L.; Liu, S.Y.; Liu, H.Z. Isolation and functional diversification of dihydroflavonol 4-Reductase gene HvDFR from Hosta ventricosa indicate its role in driving anthocyanin accumulation. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, e2010389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhou, N.N.; Feng, C.; Sun, S.Y.; Tang, M.; Tang, X.X.; Ju, Z.G.; Yi, Y. Functional analysis of a dihydroflavonol 4-reductase gene in Ophiorrhiza japonica (OjDFR1) reveals its role in the regulation of anthocyanin. Peer J 2021, 9, e12323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhou, N.N.; Wang, Y.H.; Sun, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhigang Ju, Z.G.; Yi, Y. Characterization and functional analysis of RdDFR1 regulation on flower color formation in Rhododendron delavayi. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 169, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.X.; Guo, C.C.; Shan, H.Y.; Kong, H.Z. Divergence of duplicate genes in exon-intron structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.W.; Lu, D.D.; Li, L.; Yu, Y.L.; Xu, L.J.; Dong, W.; Yang, H.Q.; Yang, Q.; Li, C.M.; Liang, H.Z. Cloning and expression analysis of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase gene from Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.). Mol. Plant Breed. 2022, 20, 5309–5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.L.; Li, Y.Z.; He, L.L.; Song, Y.H.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Z.X.; Li, P.H.; Liu, S.J. Genome-wide identification and analysis of TPS gene family and functional verification of VvTPS4 in the formation of monoterpenes in Grape. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2025, 58, 1397–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.T.; Wang, H.; Tian, Z.D.; Siyao Xin, S.Y.; Zhu, P.F. The dihydrofavonol 4-reductase BoDFR1 drives anthocyanin accumulation in pink-leaved ornamental kale. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Li, H.; Gao, M.; Guo, C.H.; Guo, D.L.; Bi, Y.D. Cloning of GmDFR gene from Soybean (Glycine max) and identification of its function on resistance to iron deficiency. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 31, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Chen, X.J.; Li, T.J.; Luo, J.; Qu, Y. Cloning and expression analysis of DFR gene from Meconopsis with different colors. Acta Agric. Boreali Sin. 2024, 39, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, F.; Jian, Y.; Huang, W.L.; Liang, S.; Jiang, M.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, Q.M.; Sun, B. Cloning and function identification of Dihydroflavonol 4-Reductase gene BoaDFR in Chinese Kale. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2021, 48, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Y.; Li, C.H.; Liu, X.; Liao, X.S.; Rong, D.Y. Cloning and subcellular localization analysis of LcDRF1 and LcDRF2 in Loropetalum chinense var. rubrum. J. South. Agric. 2020, 51, 2865–2874. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Peng, Q.Z.; Li, K.G.; Xie, D.Y. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a dihydroflavonol 4-reductase from Vitis bellula. Molecules 2018, 23, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Meng, L.; Han, K.T.; Sun, Y.; Dai, S.L. Isolation and expression analysis of key genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis of Cineraria. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2009, 36, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.X.; Wang, Q.H.; Yang, G.X.; Jia, Y.H.; Xie, X.H.; Wu, Y.Y. Cloning and analysis of RhDFR gene in Rhododendron hybridum Hort. Acta Bot. Boreat. Occident. Sin. 2023, 43, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Y.H.; Zhang, L.Y.; Liu, H.; Luo, C.; Cheng, X.; Gao, K.; Huang, C.L.; Chen, D.L. Cloning and expression analysis of CmDFRa gene in Chrysanthemum × morifolium. Mol. Plant Breed. 2024, 4, 1–12. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/46.1068.S.20240424.0948.005 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Lim, S.H.; Park, B.; Kim, D.H.; Park, S.; Yang, J.H.; Jung, J.A.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, J.Y. Cloning and functional characterization of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase gene involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis of Chrysanthemum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, D.; Su, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, C.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L.; Qiao, M.; Yang, H.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification of the DFR Gene Family in Lonicera japonica Thunb. and Response to Drought and Salt Stress. Genes 2025, 16, 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121453

Lu D, Su X, Sun Y, Li L, Yu Y, Li C, Cao Y, Wang L, Qiao M, Yang H, et al. Genome-Wide Identification of the DFR Gene Family in Lonicera japonica Thunb. and Response to Drought and Salt Stress. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121453

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Dandan, Xiaoyu Su, Yao Sun, Lei Li, Yongliang Yu, Chunming Li, Yiwen Cao, Lina Wang, Meiyu Qiao, Hongqi Yang, and et al. 2025. "Genome-Wide Identification of the DFR Gene Family in Lonicera japonica Thunb. and Response to Drought and Salt Stress" Genes 16, no. 12: 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121453

APA StyleLu, D., Su, X., Sun, Y., Li, L., Yu, Y., Li, C., Cao, Y., Wang, L., Qiao, M., Yang, H., Su, M., Tan, Z., & Liang, H. (2025). Genome-Wide Identification of the DFR Gene Family in Lonicera japonica Thunb. and Response to Drought and Salt Stress. Genes, 16(12), 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121453