Bridging East and West: Real-World Clinicogenomic Landscape of Metastatic NSCLC in Türkiye

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

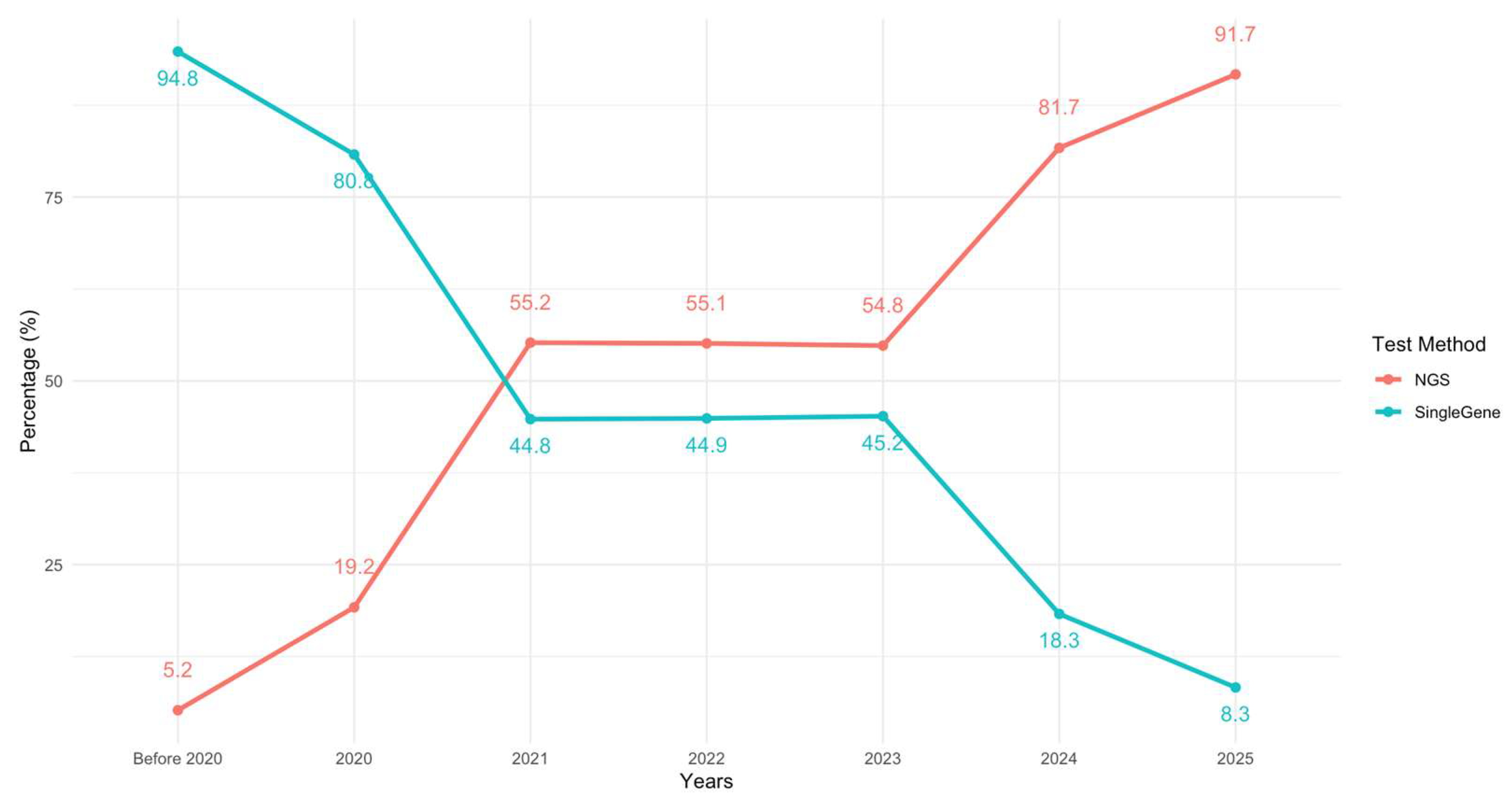

3.2. Molecular Testing

3.3. Driver Mutations

3.4. Frequency of Targetable Mutations by Histologic Subtype

3.5. PD-L1 Expression and Association with Oncogenic Driver Mutations

3.6. Co-Mutations in NGS-Tested Patients

3.7. Associations Between Clinical Characteristics and Driver Mutations

3.8. Treatment and Follow-Up

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sonkin, D.; Thomas, A.; Teicher, B.A. Cancer treatments: Past, present, and future. Cancer Genet. 2024, 286–287, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, M.S.C.; Mok, K.K.S.; Mok, T.S.K. Developments in targeted therapy & immunotherapy-how non-small cell lung cancer management will change in the next decade: A narrative review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2023, 11, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riely, G.J.; Wood, D.E.; Aisner, D.L.; Loo, B.W., Jr.; Axtell, A.L.; Bauman, J.R.; Bharat, A.; Chang, J.Y.; Desai, A.; Dilling, T.J.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 7.2025. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2025, 23, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeman, N.I.; Cagle, P.T.; Aisner, D.L.; Arcila, M.E.; Beasley, M.B.; Bernicker, E.H.; Colasacco, C.; Dacic, S.; Hirsch, F.R.; Kerr, K.; et al. Updated Molecular Testing Guideline for the Selection of Lung Cancer Patients for Treatment With Targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Guideline From the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018, 142, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cangır, A.K.; Yumuk, P.F.; Sak, S.D.; Akyürek, S.; Eralp, Y.; Yılmaz, Ü.; Selek, U.; Eroğlu, A.; Tatlı, A.M.; Dinçbaş, F.Ö.; et al. Lung Cancer in Turkey. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Statistical Institute. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=Nufus-ve-Demografi-109 (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GATS (Global Adult Tobacco Survey) Fact Sheet, Turkey 2016. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/872 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Akkoç, Y.; Sulhan, H.; Akgöllü, E.; Çift, A. The effect of HOTAIR gene variants on the development of bladder cancer and its clinicopathological characteristics in a Caucasian population. Cancer Genet. 2025, 296–297, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agaoglu, N.B.; Unal, B.; Hayes, C.P.; Walker, M.; Ng, O.H.; Doganay, L.; Can, N.D.; Rana, H.Q.; Ghazani, A.A. Genomic disparity impacts variant classification of cancer susceptibility genes in Turkish breast cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hendriks, L.E.; Kerr, K.M.; Menis, J.; Mok, T.S.; Nestle, U.; Passaro, A.; Peters, S.; Planchard, D.; Smit, E.F.; Solomon, B.J.; et al. Oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Security Institution. Available online: https://www.sgk.gov.tr/Istatistik/Yillik/fcd5e59b-6af9-4d90-a451-ee7500eb1cb4/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Tezel, G.G.; Şener, E.; Aydın, Ç.; Önder, S. Prevalence of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in Turkish Population. Balk. Med. J. 2017, 34, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calibasi-Kocal, G.; Amirfallah, A.; Sever, T.; Umit Unal, O.; Gurel, D.; Oztop, I.; Ellidokuz, H.; Basbinar, Y. EGFR mutation status in a series of Turkish non-small cell lung cancer patients. Biomed. Rep. 2020, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melosky, B.; Kambartel, K.; Häntschel, M.; Bennetts, M.; Nickens, D.J.; Brinkmann, J.; Kayser, A.; Moran, M.; Cappuzzo, F. Worldwide Prevalence of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2022, 26, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skov, B.G.; Høgdall, E.; Clementsen, P.; Krasnik, M.; Larsen, K.R.; Sørensen, J.B.; Skov, T.; Mellemgaard, A. The prevalence of EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer in an unselected Caucasian population. J. Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 123, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahr, S.; Stoehr, R.; Geissinger, E.; Ficker, J.H.; Brueckl, W.M.; Gschwendtner, A.; Gattenloehner, S.; Fuchs, F.S.; Schulz, C.; Rieker, R.J.; et al. EGFR mutational status in a large series of Caucasian European NSCLC patients: Data from daily practice. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation status in pure squamous-cell lung cancer in Chinese patients. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Kong, W.; Yu, Z.; He, X. 29P Genomic features of Chinese lung squamous cell carcinoma patients. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, S253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Tjulandin, S.; Hagiwara, K.; Normanno, N.; Wulandari, L.; Laktionov, K.; Hudoyo, A.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.P.; Wang, M.Z.; et al. EGFR mutation prevalence in Asia-Pacific and Russian patients with advanced NSCLC of adenocarcinoma and non-adenocarcinoma histology: The IGNITE study. Lung Cancer 2017, 113, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, A.G.; Tsao, M.S.; Beasley, M.B.; Borczuk, A.C.; Brambilla, E.; Cooper, W.A.; Dacic, S.; Jain, D.; Kerr, K.M.; Lantuejoul, S.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Advances Since 2015. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gün, E.; Çakır, İ.E.; Ersöz, H.; Oflazoğlu, U.; Sertoğullarından, B. The Epidermal Growth Factor, Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase, and ROS Proto-oncogene 1 Mutation Profile of Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinomas in the Turkish Population: A Single-Center Analysis. Thorac. Res. Pract. 2024, 25, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayten, Ö.; Çalışkan, T.; Canoğlu, K.; Kaya Terzi, N.; Emirzeoğlu, L.; Okutan, O. Oncogenic Mutation Frequencies in Lung Cancer Patients. Hamidiye Med. J. 2020, 1, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, M.G.; Belluomini, L.; Smimmo, A.; Sposito, M.; Avancini, A.; Giannarelli, D.; Milella, M.; Pilotto, S.; Bria, E. Meta-analysis of the prognostic impact of TP53 co-mutations in EGFR-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2023, 184, 103929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Hou, H.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, X. Prognostic value of TP53 concurrent mutations for EGFR- TKIs and ALK-TKIs based targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzuto, F.; Hofman, V.; Bontoux, C.; Fortarezza, F.; Lunardi, F.; Calabrese, F.; Hofman, P. The significance of co-mutations in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer: Optimizing the efficacy of targeted therapies? Lung Cancer 2023, 181, 107249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciuti, B.; Arbour, K.C.; Lin, J.J.; Vajdi, A.; Vokes, N.; Hong, L.; Zhang, J.; Tolstorukov, M.Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Spurr, L.F.; et al. Diminished Efficacy of Programmed Death-(Ligand)1 Inhibition in STK11- and KEAP1-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma Is Affected by KRAS Mutation Status. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoulidis, F.; Goldberg, M.E.; Greenawalt, D.M.; Hellmann, M.D.; Awad, M.M.; Gainor, J.F.; Schrock, A.B.; Hartmaier, R.J.; Trabucco, S.E.; Gay, L.; et al. STK11/LKB1 Mutations and PD-1 Inhibitor Resistance in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, K.; Toyokawa, G.; Tagawa, T.; Kohashi, K.; Shimokawa, M.; Akamine, T.; Takamori, S.; Hirai, F.; Shoji, F.; Okamoto, T.; et al. PD-L1 expression according to the EGFR status in primary lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2018, 116, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, K.; Yu, H.A.; Wei, W.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; DeVeaux, M.; Choi, J.; Rizvi, H.; Lisberg, A.; Truini, A.; Lydon, C.A.; et al. EGFR mutation subtypes and response to immune checkpoint blockade treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, N.J.; Schneider, J.L.; Patil, T.; Zhu, V.W.; Goldman, D.A.; Yang, S.R.; Falcon, C.J.; Do, A.; Nie, Y.; Plodkowski, A.J.; et al. Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition as Monotherapy or in Combination With Chemotherapy in Metastatic ROS1-Rearranged Lung Cancers. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2021, 2, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Chakravarty, D.; Dienstmann, R.; Jezdic, S.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Lopez-Bigas, N.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Bedard, P.L.; Tortora, G.; Douillard, J.Y.; et al. A framework to rank genomic alterations as targets for cancer precision medicine: The ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets (ESCAT). Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, J.; Jang, H.L.; Hong, J.Y.; Kim, S.T.; Park, S.H.; Park, J.O.; Kim, K.M.; Geun Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Lim, S.H. Prevalence and clinical implications of PIK3CA aberrations across cancer types: A real-world next-generation sequencing approach. Cancer Genet. 2025, 296–297, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, R.; Borea, R.; Drago, F.; Russo, A.; Nigita, G.; Rolfo, C. Genetic drivers of tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer: The role of KEAP1, SMARCA4, and PTEN mutations. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e012288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Joshi, R.M.; Telang, B.; Soni, G.; Khalife, A. Overview of perspectives on cancer, newer therapies, and future directions. Oncol. Transl. Med. 2024, 10, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EGFR Mutation | ALK Fusion | ROS1 Fusion | BRAF V600E mutation | KRAS G12C mutation | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | All Patients (n = 1023) | Mutant (n = 164) | Wild (n = 856) | p | Fusion Positive (n = 51) | Wild (n = 943) | p | Fusion Positive (n = 18) | Wild (n = 909) | p | Mutant (n = 22) | Wild (n = 671) | p-Value | Mutant (n = 26) | Wild (n = 964) | p |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 64.06 ± 9.79 | 63.31 ± 11.46 | 64.21 ± 9.45 | 0.282 | 59.69 ± 11.66 | 64.22 ± 9.57 | 0.001 | 63.97 ± 9.62 | 58.83 ± 10.10 | 0.025 * | 66.91 ± 10.69 | 63.90 ± 9.44 | 0.143 * | 63.93 ± 9.76 | 64.62 ± 8.30 | 0.724 * |

| Age ≥ 65, n (%) | 505 (49.4%) | 70 (42.7%) | 433 (50.6%) | 0.064 | 17 (33.3%) | 470 (49.8%) | 0.022 | 5 (27.8%) | 446 (49.1%) | 0.074 * | 11 (50.0%) | 327 (48.7%) | 15 (57.7%) | 15 (57.7%) | 0.363 * | |

| Sex, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.982 * | 0.700 * | 0.133 * | |||||||||||

| Female | 241 (23.6%) | 90 (37.7%) | 149 (17.4%) | 27 (52.9%) | 205 (21.4%) | 4 (22.2%) | 204 (22.4%) | 4 (18.2%) | 145 (21.6%) | 3 (11.5%) | 234 (24.3%) | |||||

| Male | 782 (76.4%) | 74 (62.3%) | 707 (82.6%) | 24 (47.1%) | 738 (78.3%) | 14 (77.8%) | 705 (77.6%) | 18 (81.8%) | 526 (78.4%) | 23 (88.5%) | 730 (75.7%) | |||||

| Smoking status, n(%) (n = 958) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.462 * | 0.077 * | 0.635 * | |||||||||||

| Never-smoker | 173 (18.1%) | 78 (51.0%) | 94 (11.7%) | 24 (54.5%) | 147 (16.6%) | 2 (11.8%) | 158 (18.5%) | 3 (15.0%) | 113 (17.9%) | 3 (11.5%) | 168 (18.5%) | |||||

| Active smoker | 464 (48.4%) | 37 (24.2%) | 425 (53.0%) | 11 (25.0%) | 442 (49.8%) | 11 (64.7%) | 423 (49.6%) | 7 (35.0%) | 348 (55.0%) | 13 (50.0%) | 438 (48.3%) | |||||

| Ex-smoker | 321 (33.5%) | 38 (24.8%) | 283 (35.3%) | 9 (20.5%) | 298 (33.6%) | 4 (23.5%) | 272 (31.9%) | 10 (50.0%) | 172 (27.2%) | 10 (38.5%) | 300 (33.1%) | |||||

| Histology, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.012 * | 0.214 * | 0.082 * | |||||||||||

| Non-squamous carcinoma | 777 (76.0%) | 148 (90.2%) | 626 (73.1%) | 49 (96.1%) | 705 (74.8%) | 671 (73.8%) | 18 (100.0%) | 18 (81.8%) | 466 (69.4%) | 24 (92.3%) | 753 (78.1%) | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 246 (24.0%) | 16 (9.8%) | 230 (26.9%) | 2 (3.9%) | 238 (25.2%) | 238 (26.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (18.2%) | 205 (30.6%) | 2 (7.7%) | 211 (21.9%) | |||||

| PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1% (n = 601), n (%) | 314 (52.2%) | 38 (42.7%) | 276 (54.2%) | 0.045 | 13 (52.0%) | 298 (52.6%) | 0.956 | 2 (18.2%) | 304 (53.8%) | 0.019 * | 6 (46.2%) | 245 (52.7%) | 0.642 * | 8 (40.0%) | 293 (52.5%) | 0.271 * |

| PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% (n = 601), n (%) | 107 (17.8%) | 9 (8.4%) | 98 (19.3%) | 0.056 | 7 (28.0%) | 99 (17.5%) | 0.311 | 104 (18.4%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0.062 * | 2 (15.4%) | 77 (16.6%) | 0.893 * | 2 (10.0%) | 98 (17.6%) | 0.495 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canaslan, K.; Eken, E.; Bilici, M.; Balcıoğlu, F.M.; Öztürk, B.; Çakmak, M.; Bal, Ö.; Turhan, G.; Özdemir, F.; Arvas, H.; et al. Bridging East and West: Real-World Clinicogenomic Landscape of Metastatic NSCLC in Türkiye. Genes 2025, 16, 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121446

Canaslan K, Eken E, Bilici M, Balcıoğlu FM, Öztürk B, Çakmak M, Bal Ö, Turhan G, Özdemir F, Arvas H, et al. Bridging East and West: Real-World Clinicogenomic Landscape of Metastatic NSCLC in Türkiye. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121446

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanaslan, Kübra, Emre Eken, Mehmet Bilici, Fahriye Merve Balcıoğlu, Banu Öztürk, Mehmet Çakmak, Öznur Bal, Görkem Turhan, Feyyaz Özdemir, Hayati Arvas, and et al. 2025. "Bridging East and West: Real-World Clinicogenomic Landscape of Metastatic NSCLC in Türkiye" Genes 16, no. 12: 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121446

APA StyleCanaslan, K., Eken, E., Bilici, M., Balcıoğlu, F. M., Öztürk, B., Çakmak, M., Bal, Ö., Turhan, G., Özdemir, F., Arvas, H., Urakçı, Z., Çiçek, E., Turna, Z. H., & Karaoğlu, A. (2025). Bridging East and West: Real-World Clinicogenomic Landscape of Metastatic NSCLC in Türkiye. Genes, 16(12), 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121446