Role of Genetic and Epigenetic Biomarkers in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiological and Clinical Context of TRD

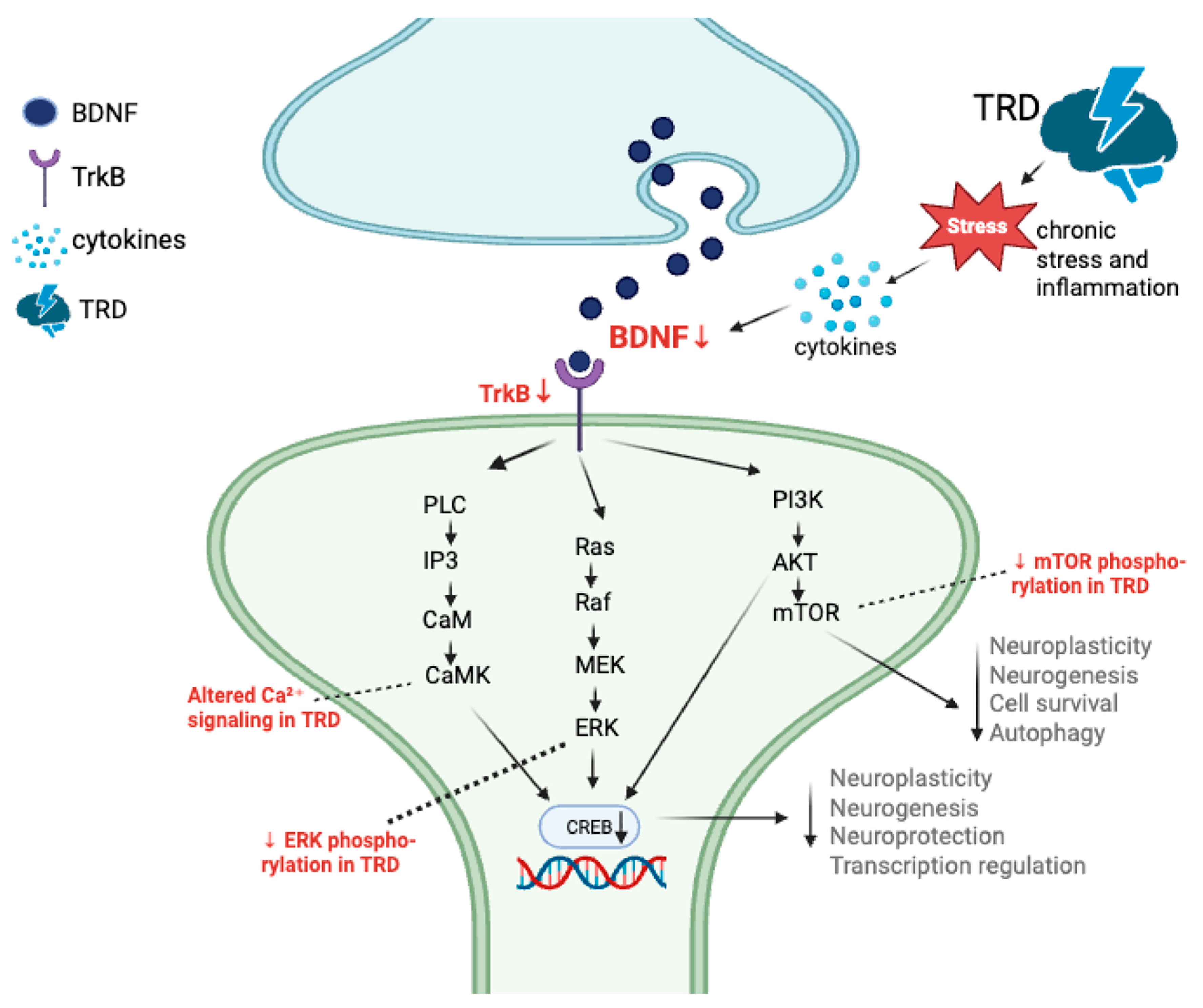

1.2. Neuroplasticity as a Core Mechanism of Treatment Response

1.3. Pharmacogenomic Foundations and Genetic Variability

1.4. Neurotrophic and Synaptic Gene Networks

1.5. Glutamatergic Dysregulation and Synaptic Signaling

1.6. Ketamine and Rapid-Acting Antidepressant Mechanisms

1.7. Epigenetic and RNA-Based Regulation of Neuroplasticity

1.8. Rationale and Objectives of the Review

2. Materials and Methods

- Peer-reviewed original research articles or reviews published in English.

- Human studies or translational studies with direct relevance to major depressive disorder or treatment-resistant depression.

- Investigations of DNA variants (candidate gene studies, GWAS, multi-omic models with genetic focus) or RNA-based biomarkers (gene expression, microRNAs).

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Predictors of TRD

3.2. Epigenetic Regulation in TRD

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Predictors and Convergent Signaling

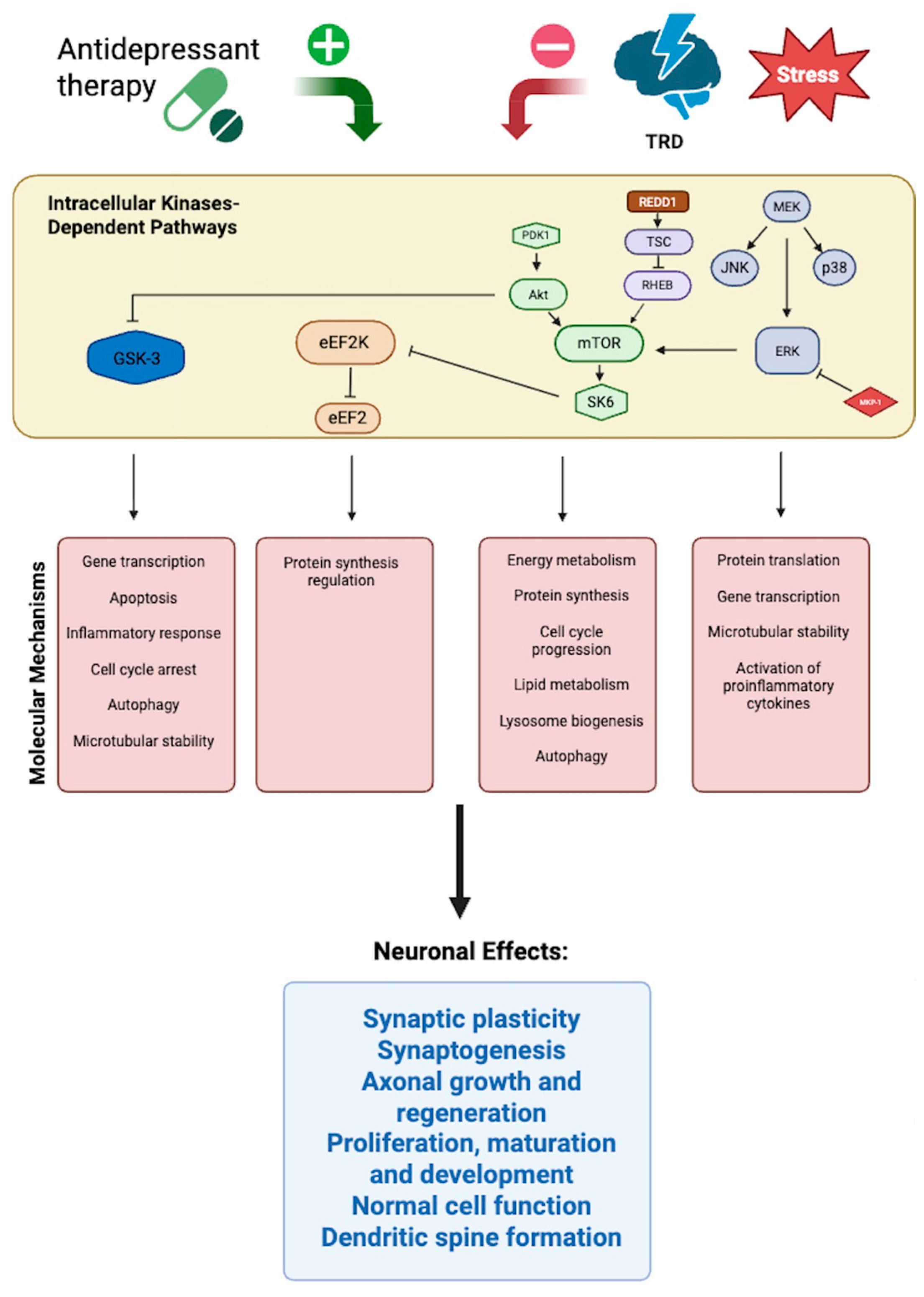

4.2. Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Networks

4.3. Epigenetic and RNA-Based Modulation of Neuroplasticity

4.4. Translational and Clinical Implications

- Patient stratification—Combining pre-treatment genetic markers (e.g., BDNF rs6265, GRIN2B polymorphisms) with circulating miRNAs could help identify patients most likely to benefit from ketamine or ECT.

- Response monitoring—Longitudinal profiling of miRNAs offers real-time indicators of treatment efficacy, particularly for ECT and ketamine.

- Drug development—Pathways such as TrkB signaling, NMDA/AMPA receptor balance, and miRNA-regulated immune–neuroplastic crosstalk represent promising therapeutic targets.

- Cross-treatment biomarkers—The overlap of DNA and miRNA predictors across ketamine, ECT, and TMS suggests that unified biomarker panels may guide multimodal treatment strategies.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Anterior cingulate cortex |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| AMPA | α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor |

| ARC | Activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CaM | Calmodulin |

| CaMK | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase |

| CACNA1C | Calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 C |

| CLOCK | Circadian locomotor output cycles kaput |

| COMT | Catechol-O-methyltransferase |

| CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein |

| DHPS | Deoxyhypusine synthase |

| DOHH | Deoxyhypusine hydroxylase |

| ECT | Electroconvulsive therapy |

| eEF2 | Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 |

| eEF2K | Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase |

| eIF5A | Eukaryotic initiation factor 5A |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FKBP5 | FK506 binding protein 5 |

| FT3 | Free triiodothyronine |

| GSK3B | Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta |

| GRIA2/3 | Glutamate ionotropic AMPA receptor subunit 2/3 |

| GRIN2A/2B | Glutamate ionotropic NMDA receptor subunit 2A/2B |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis |

| IL6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IL6R | Interleukin 6 receptor |

| IP3 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MAPK1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 |

| MEK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| MKP-1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NMDAR | N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor |

| NR3C1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 (glucocorticoid receptor) |

| NTRK2 (TrkB) | Neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (tropomyosin receptor kinase B) |

| PDK1 | 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PLC | Phospholipase C |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| RAF | Rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma kinase |

| RAS | Ras GTPase protein |

| REDD1 | Regulated in development and DNA damage response 1 |

| RHEB | Ras homolog enriched in brain |

| SK6 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 |

| SYN1 | Synapsin I |

| TNFAIP3 | Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 |

| TMS | Transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| TSC | Tuberous sclerosis complex |

| TRD | Treatment-resistant depression |

| VAMP2 | Vesicle associated membrane protein 2 |

References

- Bains, N.; Abdijadid, S. Major Depressive Disorder. [Updated]. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559078/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Depression Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Koretz, D.; Merikangas, K.R.; Rush, A.J.; Walters, E.E.; Wang, P.S.; National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003, 289, 3095–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, D.M.; Canuso, C.M.; Daly, E.; Johnson, J.C.; Fu, D.J.; Doherty, T.; Blauer-Peterson, C.; Cepeda, M.S. Suicide-specific mortality among patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, major depressive disorder with prior suicidal ideation or suicide attempts, or major depressive disorder alone. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rush, A.J.; Trivedi, M.H.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Stewart, J.W.; Warden, D.; Niederehe, G.; Thase, M.E.; Lavori, P.W.; Lebowitz, B.D.; et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: A STAR*D report. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1905–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voineskos, D.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Blumberger, D.M. Management of Treatment-Resistant Depression: Challenges and Strategies. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saelens, J.; Gramser, A.; Watzal, V.; Zarate, C.A., Jr.; Lanzenberger, R.; Kraus, C. Relative effectiveness of antidepressant treatments in treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 50, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brown, S.; Rittenbach, K.; Cheung, S.; McKean, G.; MacMaster, F.P.; Clement, F. Current and Common Definitions of Treatment-Resistant Depression: Findings from a Systematic Review and Qualitative Interviews. Can. J. Psychiatry 2019, 64, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maj, M.; Stein, D.J.; Parker, G.; Zimmerman, M.; Fava, G.A.; De Hert, M.; Demyttenaere, K.; McIntyre, R.S.; Widiger, T.; Wittchen, H.U. The clinical characterization of the adult patient with depression aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kasper, S. Is treatment-resistant depression really resistant? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 58, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, M.; Sanches, M. Experimental Therapeutics in Treatment-Resistant Major Depressive Disorder. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2021, 13, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kubitz, N.; Mehra, M.; Potluri, R.C.; Garg, N.; Cossrow, N. Characterization of treatment resistant depression episodes in a cohort of patients from a US commercial claims database. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Alsuwaidan, M.; Baune, B.T.; Berk, M.; Demyttenaere, K.; Goldberg, J.F.; Gorwood, P.; Ho, R.; Kasper, S.; Kennedy, S.H.; et al. Treatment-resistant depression: Definition, prevalence, detection, management, and investigational interventions. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ormel, J.; Kessler, R.C.; Schoevers, R. Depression: More treatment but no drop in prevalence: How effective is treatment? And can we do better? Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lépine, J.P.; Briley, M. The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2011, 7 (Suppl. 1), 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Souery, D.; Oswald, P.; Massat, I.; Bailer, U.; Bollen, J.; Demyttenaere, K.; Kasper, S.; Lecrubier, Y.; Montgomery, S.; Serretti, A.; et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: Results from a European multicenter study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carlo, V.; Calati, R.; Serretti, A. Socio-demographic and clinical predictors of non-response/non-remission in treatment resistant depressed patients: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 240, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kautzky, A.; Baldinger-Melich, P.; Kranz, G.S.; Vanicek, T.; Souery, D.; Montgomery, S.; Mendlewicz, J.; Zohar, J.; Serretti, A.; Lanzenberger, R.; et al. A New Prediction Model for Evaluating Treatment-Resistant Depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrman, H.; Patel, V.; Kieling, C.; Berk, M.; Buchweitz, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Furukawa, T.A.; Kessler, R.C.; Kohrt, B.A.; Maj, M.; et al. Time for united action on depression: A Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet 2022, 399, 957–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222, Erratum in Lancet 2020, 396, 1562. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32226-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mann, J.J.; Michel, C.A.; Auerbach, R.P. Improving Suicide Prevention Through Evidence-Based Strategies: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 178, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delgado, P.L. Depression: The case for a monoamine deficiency. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 61 (Suppl. 6), 7–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major depressive disorder: Hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, X.T. The involvement of K+ channels in depression and pharmacological effects of antidepressants on these channels. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, I.; Deacon, B.J.; Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Scoboria, A.; Moore, T.J.; Johnson, B.T. Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: A meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Chaimani, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Leucht, S.; Ruhe, H.G.; Turner, E.H.; Higgins, J.P.T.; et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trivedi, M.H.; Rush, A.J.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Warden, D.; Ritz, L.; Norquist, G.; Howland, R.H.; Lebowitz, B.; McGrath, P.J.; et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: Implications for clinical practice. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, R.S.; Aghajanian, G.K. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: Potential therapeutic targets. Science 2012, 338, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krystal, J.H.; Abdallah, C.G.; Sanacora, G.; Charney, D.S.; Duman, R.S. Ketamine: A Paradigm Shift for Depression Research and Treatment. Neuron 2019, 101, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Allen, J.; Romay-Tallon, R.; Brymer, K.J.; Caruncho, H.J.; Kalynchuk, L.E. Mitochondria and Mood: Mitochondrial Dysfunction as a Key Player in the Manifestation of Depression. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cai, L.; Xu, J.; Liu, J.; Luo, H.; Yang, R.; Gui, X.; Wei, L. miRNAs in treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, R.S.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Altered Connectivity in Depression: GABA and Glutamate Neurotransmitter Deficits and Reversal by Novel Treatments. Neuron 2019, 102, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdallah, C.G.; Sanacora, G.; Duman, R.S.; Krystal, J.H. The neurobiology of depression, ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: Is it glutamate inhibition or activation? Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 190, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Castrén, E.; Monteggia, L.M. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Signaling in Depression and Antidepressant Action. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 90, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohoff, F.W. Overview of the genetics of major depressive disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2010, 12, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Porcelli, S.; Drago, A.; Fabbri, C.; Gibiino, S.; Calati, R.; Serretti, A. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressant response. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2011, 36, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Binder, E.B.; Salyakina, D.; Lichtner, P.; Wochnik, G.M.; Ising, M.; Pütz, B.; Papiol, S.; Seaman, S.; Lucae, S.; Kohli, M.A.; et al. Polymorphisms in FKBP5 are associated with increased recurrence of depressive episodes and rapid response to antidepressant treatment. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekman, M.; Laje, G.; Charney, D.; Rush, A.J.; Wilson, A.F.; Sorant, A.J.; Lipsky, R.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Manji, H.; McMahon, F.J.; et al. The FKBP5-gene in depression and treatment response--An association study in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) Cohort. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 63, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kautzky, A.; Dold, M.; Bartova, L.; Spies, M.; Kranz, G.S.; Souery, D.; Montgomery, S.; Mendlewicz, J.; Zohar, J.; Fabbri, C.; et al. Clinical factors predicting treatment resistant depression: Affirmative results from the European multicenter study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 139, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tansey, K.E.; Guipponi, M.; Hu, X.; Domenici, E.; Lewis, G.; Malafosse, A.; Wendland, J.R.; Lewis, C.M.; McGuffin, P.; Uher, R. Contribution of common genetic variants to antidepressant response. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, C.; Kasper, S.; Kautzky, A.; Bartova, L.; Dold, M.; Zohar, J.; Souery, D.; Montgomery, S.; Albani, D.; Raimondi, I.; et al. Genome-wide association study of treatment-resistance in depression and meta-analysis of three independent samples. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 214, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.; Lima, L.; Carvalho, S.; Silva, D.; Pereira, A.; Madeira, N. The Impact of BDNF, NTRK2, NGFR, CREB1, GSK3B, AKT, MAPK1, MTOR, PTEN, ARC, and SYN1 Genetic Polymorphisms in Antidepressant Treatment Response Phenotypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, M.; Fortaner-Uyà, L.; Lorenzi, C.; Mandelli, L.; Menculini, G.; Tempesta, D.; Calati, R.; Fabbri, C.; Serretti, A. Association between NTRK2 Polymorphisms, Hippocampal Volumes and Treatment Resistance in Major Depressive Disorder. Genes 2023, 14, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, E.; Erkoreka, L.; Moreno-Calle, T.; Berjano, B.; Gonzalez-Pinto, A.; Basterreche, N.; Arrue, A. Genetic variables of the glutamatergic system associated with treatment-resistant depression: A review of the literature. World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H.; Kao, C.F.; Tsai, S.J.; Li, C.T.; Lin, W.C.; Hong, C.J.; Bai, Y.M.; Tu, P.C.; Su, T.P. Treatment response to low-dose ketamine infusion for treatment-resistant depression: A gene-based genome-wide association study. Genomics 2021, 113, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelada, M.I.; Garrido, V.; Liberona, A.; Jones, N.; Zúñiga, K.; Silva, H.; Nieto, R.R. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) as a Predictor of Treatment Response in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numakawa, T.; Odaka, H.; Adachi, N. Actions of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Glucocorticoid Stress in Neurogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, L.; Gong, W.K.; Yang, C.P.; Shao, C.C.; Song, N.N.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhou, L.Q.; Zhang, K.S.; Li, S.; Huang, Z.; et al. Pten is a key intrinsic factor regulating raphe 5-HT neuronal plasticity and depressive behaviors in mice. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cruceanu, C.; Kutsarova, E.; Chen, E.S.; Checknita, D.R.; Nagy, C.; Lopez, J.P.; Alda, M.; Rouleau, G.A.; Turecki, G. DNA hypomethylation of Synapsin II CpG islands associates with increased gene expression in bipolar disorder and major depression. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karege, F.; Perroud, N.; Burkhardt, S.; Schwald, M.; Ballmann, E.; La Harpe, R.; Malafosse, A. Alteration in kinase activity but not in protein levels of protein kinase B and glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in ventral prefrontal cortex of depressed suicide victims. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Bijur, G.N.; Jope, R.S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta, mood stabilizers, and neuroprotection. Bipolar Disord. 2002, 4, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, N.; Lee, B.; Liu, R.J.; Banasr, M.; Dwyer, J.M.; Iwata, M.; Li, X.Y.; Aghajanian, G.; Duman, R.S. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science 2010, 329, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanacora, G.; Treccani, G.; Popoli, M. Towards a glutamate hypothesis of depression: An emerging frontier of neuropsychopharmacology for mood disorders. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berman, R.M.; Cappiello, A.; Anand, A.; Oren, D.A.; Heninger, G.R.; Charney, D.S.; Krystal, J.H. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2000, 47, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, Y. Evidence demonstrating role of microRNAs in the etiopathology of major depression. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2011, 42, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lopez, J.P.; Lim, R.; Cruceanu, C.; Crapper, L.; Fasano, C.; Labonte, B.; Maussion, G.; Yang, J.P.; Yerko, V.; Vigneault, E.; et al. miR-1202 is a primate-specific and brain-enriched microRNA involved in major depression and antidepressant treatment. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Belzeaux, R.; Lin, R.; Turecki, G. Potential Use of MicroRNA for Monitoring Therapeutic Response to Antidepressants. CNS Drugs 2017, 31, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cătană, C.S.; Mureșanu, D.F.; Bădescu, S.; Perju-Dumbravă, L.; Chirilă, I.; Manea, M. MicroRNAs: A Novel Approach for Monitoring Treatment Response in Major Depressive Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaurani, L.; Besse, M.; Methfessel, I.; Methi, A.; Zhou, J.; Pradhan, R.; Burkhardt, S.; Kranaster, L.; Sartorius, A.; Habel, U.; et al. Baseline levels of miR-223-3p correlate with the effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy in patients with major depression. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Galbiati, C.; Dattilo, V.; Bortolomasi, M.; Vitali, E.; Abate, M.; Menesello, V.; Meattini, M.; Carvalho Silva, R.; Gennarelli, M.; Bocchio Chiavetto, L.; et al. Plasma microRNA Levels After Electroconvulsive Therapy in Treatment-Resistant Depressed Patients. J. ECT, 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statharakos, N.; Savvidis, V.; Gravanis, T. Towards Precision ECT: A systematic review of epigenetic biomarkers in treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatriki, 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, C.E.; Altinay, M.; Bailey, K.; Bhati, M.T.; Carr, B.R.; Conroy, S.K.; Khurshid, K.; McDonald, W.M.; Mickey, B.J.; Murrough, J.W.; et al. Genetics of Response to ECT, TMS, Ketamine and Esketamine. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2025, 198, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kang, M.J.Y.; Hawken, E.; Vazquez, G.H. The Mechanisms Behind Rapid Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine: A Systematic Review with a Focus on Molecular Neuroplasticity. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 860882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Duman, R.S.; Voleti, B. Signaling pathways underlying the pathophysiology and treatment of depression: Novel mechanisms for rapid-acting agents. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nemec, C.M.; Singh, A.K.; Ali, A.; Tseng, S.C.; Syal, K.; Ringelberg, K.J.; Ho, Y.H.; Hintermair, C.; Ahmad, M.F.; Kar, R.K.; et al. Noncanonical CTD kinases regulate RNA polymerase II in a gene-class-specific manner. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kajumba, M.M.; Kakooza-Mwesige, A.; Nakasujja, N.; Koltai, D.; Canli, T. Treatment-resistant depression: Molecular mechanisms and management. Mol. Biomed. 2024, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yuan, L.L.; Wauson, E.; Duric, V. Kinase-mediated signaling cascades in mood disorders and antidepressant treatment. J. Neurogenetics 2016, 30, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hall, S.; Parr, B.-A.; Hussey, S.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Arora, D.; Grant, G.D. The neurodegenerative hypothesis of depression and the influence of antidepressant medications. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 983, 176967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Kar, R.K.; Banka, S.; Ziegler, A.; Chung, W.K. Post-translational formation of hypusine in eIF5A: Implications in human neurodevelopment. Amino Acids 2021, 54, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, R.K.; Hanner, A.S.; Starost, M.F.; Springer, D.; Mastracci, T.L.; Mirmira, R.G.; Park, M.H. Neuron-specific ablation of eIF5A or deoxyhypusine synthase leads to impairments in growth, viability, neurodevelopment, and cognitive functions in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, T.; Hammer, J.; Rundén-Pran, E.; Roberg, B.; Thomas, M.J.; Osen, K.; Davanger, S.; Laake, P.; Torgner, I.A.; Lee, T.S.; et al. Increased expression of phosphate-activated glutaminase in hippocampal neurons in human mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Acta Neuropathol. 2007, 113, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, R.K. Recent insights of molecular approaches to study brain tumor associated seizure and epilepsy. In Recent Trends in Diabetes and Cancer Research and its Management. Iterative International Publishers (IIP); Selfypage Developers Pvt Ltd.: Karnataka, India, 2024; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, P.; Shukla, S.; Mondal, M.; Kar, R.K.; Siddiqui, J.A. The nexus of long noncoding RNAs, splicing factors, alternative splicing and their modulations. RNA Biol. 2023, 21, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Full Title | Methodology/Biomarker Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Cai et al. (2024) [33] | miRNAs in treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review | Systematic review; Epigenetics (microRNAs) |

| Cătană et al. (2025) [60] | MicroRNAs: a novel approach for monitoring treatment response in major depressive disorder? | Review; Epigenetics (microRNAs) |

| Chen et al. (2021) [47] | Treatment response to low-dose ketamine infusion for treatment-resistant depression: a gene-based genome-wide association study | Candidate gene-based GWAS in TRD; Genetics |

| Franklin et al. (2025) [64] | Genetics of Response to ECT, TMS, Ketamine and Esketamine | Systematic review of candidate genes, GWAS, and PRS; Genetics |

| Galbiati et al. (2025) [62] | Plasma microRNA levels after electroconvulsive therapy in treatment-resistant depressed patients | Clinical plasma miRNA profiling; Epigenetics |

| Kang et al. (2025) [65] | Genetic predictors of ketamine/esketamine response in treatment-resistant depression | Pharmacogenomic association study; Genetics |

| Kaurani et al. (2023) [61] | MicroRNA modulation after electroconvulsive therapy: markers of response in treatment-resistant depression | Clinical study of plasma miRNAs pre/post ECT; Epigenetics |

| Paolini et al. (2023) [45] | Association between NTRK2 polymorphisms, hippocampal volumes and treatment resistance in major depressive disorder | Neuroimaging–genetic study (3T MRI + genotyping); Genetics |

| Santos et al. (2023) [44] | BDNF, NTRK2, NGFR, CREB1, GSK3B, AKT, MAPK1, MTOR, PTEN, ARC, and SYN1 genetic polymorphisms in antidepressant treatment response phenotypes | Candidate gene analysis in MDD/TRD; Genetics |

| Saez et al. (2022) [46] | Genetic variables of the glutamatergic system associated with treatment-resistant depression: a review of the literature | Narrative/systematic review; Genetics (NMDA/AMPA pathways) |

| Statharakos et al. (2023) [63] | Towards precision ECT: a systematic review of epigenetic biomarkers in treatment-resistant depression | Systematic review; Epigenetics |

| Zelada et al. (2025) [48] | Genetics of response to electroconvulsive therapy, TMS, ketamine and esketamine: insights from the Gen-ECT-ic consortium | Multi-center, multi-omic integration; machine learning; Genetics (PRS/consortium) |

| Author (Year) | Sample/Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Santos et al. (2023) [44] | 80 MDD patients, Texas Medication Algorithm; candidate gene analysis | TRD risk: PTEN rs12569998, SYN1 rs1142636, BDNF rs6265. Relapse: MAPK1 rs6928 (protective), GSK3B rs6438552 (higher relapse risk). Pathways: synaptic transmission, glutamatergic signaling. |

| Saez et al. (2022) [46] | Systematic review of glutamatergic genetics | GRIN2B polymorphisms (rs1805502, rs1806201, rs890) linked to TRD, suicidality, low ACC glutamate. GRIN2A rs16966731 linked to ketamine response. GRIA2/GRIA3 variants linked to MDD onset and suicidal ideation. |

| Paolini et al. (2023) [45] | 121 MDD inpatients; 3T MRI + genotyping | NTRK2 rs1948308 heterozygotes → smaller hippocampal volumes, higher TRD risk. Effect partly mediated by hippocampal volume. No BDNF associations (including Val66Met). |

| Chen et al. (2021) [47] | 65 TRD patients, low-dose ketamine; candidate gene-based GWAS | Predictors: BDNF rs2049048, NTRK2 variants (rs10217777, rs10868590, rs77918527). GRIN2A, GRIN2B, GRIN2C, GRIN3A linked to rapid/sustained response. GRIN2A/2B variants associated with ketamine/norketamine levels. |

| Kang et al. (2025) [65] | TRD patients treated with ketamine/esketamine; pharmacogenomic analysis | Novel associations: SYNGR1, VAMP2 (synaptic vesicle trafficking); IL6R, TNFAIP3 (immune regulation). Pathways: synapse organization, cytokine signaling. Gene–gene interactions: inflammatory variants modulate ketamine efficacy. |

| Zelada et al. (2025) [48] | Multi-center; genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, clinical data; machine learning | Composite panels (BDNF, NTRK2, GRIN2A/2B, IL6, TNFAIP3) → AUC > 0.80. Combined glutamatergic + immune loci improved prediction of ketamine response. |

| Franklin et al. (2025) [64] | Systematic review of 34 candidate gene studies and 9 GWAS across ECT, TMS, ketamine, and esketamine | No single variant consistently predicted outcomes. BDNF and COMT findings were mixed; GWAS remain underpowered but point to glutamatergic and immune processes. Registry-based studies showed depression PRS predicted poorer ECT response, while bipolar PRS predicted better response. Polygenic and integrative approaches show greatest promise. |

| Author (Year) | Sample/Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Cătană et al. (2025) [60] | Review of blood-based miRNA biomarkers | Highlighted miR-30a, miR-133b, miR-16, let-7 family; drug-specific modulation (miR-1202 with citalopram, miR-146a-5p with duloxetine); normalization after effective treatment. |

| Kaurani et al. (2023) [61] | ECT patients, miRNA profiling | Differential regulation of miR-146a, miR-223, miR-126; linked to immune modulation and neuronal plasticity; proposed as ECT-response biomarkers. |

| Galbiati et al. (2025) [62] | Plasma miRNA in TRD patients before/after ECT | Responders showed ↓miR-223-3p, ↓miR-146a-5p; non-responders showed no change; supports use as response-tracking markers. |

| Cai et al. (2024) [33] | Systematic review of MDD/TRD miRNAs | Consistent evidence for miR-1202, miR-16, miR-135, miR-124, miR-146a; central roles in plasticity, serotonergic signaling, and neuroinflammation. |

| Statharakos et al. (2023) [63] | Review of ECT and ketamine miRNA studies | Overlap in regulation of miR-29 family, miR-132, miR-212; both ECT and ketamine modulated miR-29a/c; linked to neuroprotection and plasticity; preliminary evidence for cross-modality biomarkers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sulić, P.; Ražić Pavičić, A.; Đapić Ivančić, B.; Božina, T.; Božina, N.; Živković, M. Role of Genetic and Epigenetic Biomarkers in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Literature Review. Genes 2025, 16, 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121443

Sulić P, Ražić Pavičić A, Đapić Ivančić B, Božina T, Božina N, Živković M. Role of Genetic and Epigenetic Biomarkers in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Literature Review. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121443

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulić, Petra, Andrea Ražić Pavičić, Biljana Đapić Ivančić, Tamara Božina, Nada Božina, and Maja Živković. 2025. "Role of Genetic and Epigenetic Biomarkers in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Literature Review" Genes 16, no. 12: 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121443

APA StyleSulić, P., Ražić Pavičić, A., Đapić Ivančić, B., Božina, T., Božina, N., & Živković, M. (2025). Role of Genetic and Epigenetic Biomarkers in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Literature Review. Genes, 16(12), 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121443