Host Immunogenetics and Chronic HCV Infection Shape Atopic Risk in Pediatric Beta-Thalassemia: A Genotype–Phenotype Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Clinical and Allergy Assessment

2.3. IgE Quantification

2.4. Virological Testing

2.5. Genotyping Procedures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

| Parameter | Subgroup | Mean IgE (IU/mL) | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCV RNA | Positive (n = 19) | 17.2 | ns |

| HCV RNA | Negative (n = 18) | 17.26 | - |

| Transfusion Reaction | Present (n = 5) | 81.0 | p < 0.05 |

| Transfusion Reaction | Absent (n = 41) | 21.0 | - |

| Splenectomy + HCV-negative | Yes (n = 4) | Highest observed values | Descriptive only |

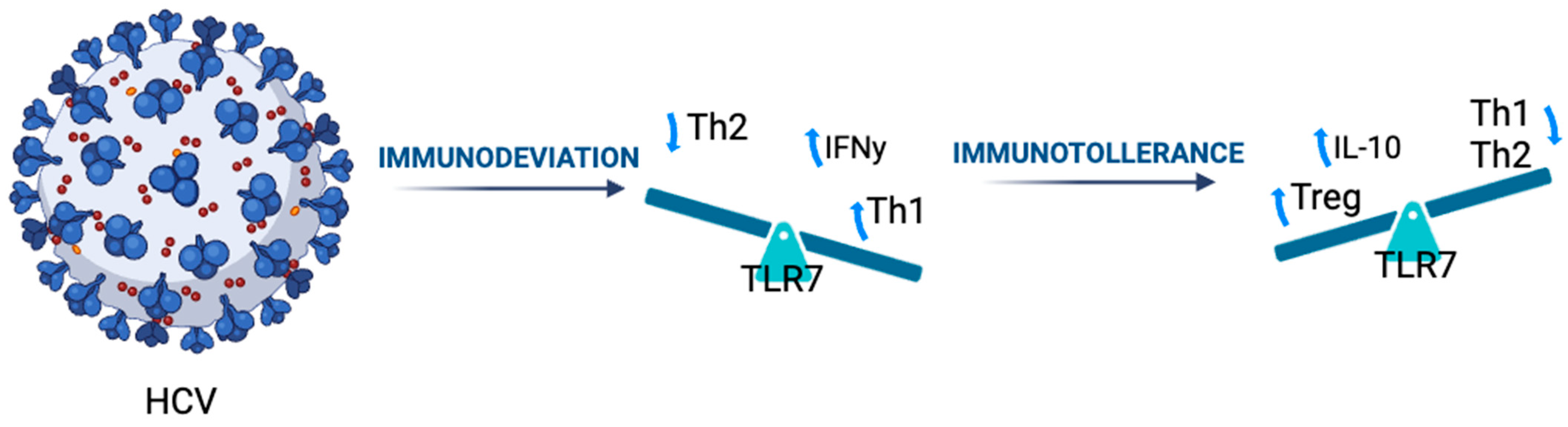

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| IL10 | Interleukin 10 |

| TLR7 | Toll-Like Receptor 7 |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cell |

| MIS-C | Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children |

| ATP6V1B2 | ATPase H+ Transporting V1 Subunit B2 |

| CF | Cystic Fibrosis |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| Th | T-helper |

References

- Cunningham, M.J. Update on Thalassemia: Clinical Care and Complications. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 24, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, M.J.; Macklin, E.A.; Neufeld, E.J.; Cohen, A.R. Thalassemia Clinical Research Network. Complications of beta-thalassemia major in North America. Blood 2004, 104, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, S.F.; Yi, Q.L.; Fan, W.; Scalia, V.; Kleinman, S.H.; Vamvakas, E.C. Current incidence and estimated residual risk of transfusion-transmitted infections in donations made to Canadian Blood Services. Transfusion 2007, 47, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, J.P.; Thomas, I.; Sauleda, S. Nucleic acid testing for emerging viral infections. Transfus. Med. Oxf. Engl. 2002, 12, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inati, A.; Taher, A.; Ghorra, S.; Koussa, S.; Taha, M.; Aoun, E.; Sharara, A.I. Efficacy and tolerability of peginterferon alpha-2a with or without ribavirin in thalassaemia major patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Br. J. Haematol. 2005, 130, 644–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A. Carrier screening and genetic counselling in β-thalassemia. Int. J. Hematol. 2002, 76, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M.; Walters, M.C. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for thalassemia and sickle cell disease: Past, present and future. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2008, 41, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-Y.; Liang, D.-C.; Liu, H.-C.; Chang, F.; Wang, C.; Chan, Y.; Lin, M. Alloimmunization among patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia in Taiwan. Transfus. Med. 2006, 16, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sestito, S.; Parisi, F.; Tallarico, V.; Cardiology, S.I.F.O.P.; Tarsitano, F.; Roppa, K.; Pensabene, L.; Chimenz, R.; Ceravolo, G.; Calabrò, M.P.; et al. Cardiac involvement in lysosomal storage diseases. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scavone, M.; Tallarico, V.; Stefanelli, E.; Cardiology, S.I.F.O.P.; Parisi, F.; De Sarro, R.; Salpietro, C.; Ceravolo, G.; Sestito, S.; Pensabene, L.; et al. Cardiac malformations in children with congenital hypothyroidism. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Linganagouda, S.; Jadhav, R.S.; Verma, S.; Bharaswadkar, R.S. Autosomal Recessive Hyper-IgE Syndrome in a Child with Beta Thalassemia Trait: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e61864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pembrey, L.; Waiblinger, D.; Griffiths, P.; Wright, J. Age at cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus and varicella zoster virus infection and risk of atopy: The Born in Bradford cohort, UK. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 30, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadelain, M.; Lisowski, L.; Samakoglu, S.; Rivella, S.; May, C.; Riviere, I. Progress Toward the Genetic Treatment of the β-Thalassemias. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1054, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppari, C.; Ceravolo, G.; Ceravolo, M.D.; Cardiology, S.I.F.O.P.; Sestito, S.; Nicocia, G.; Chimenz, R.; Salpietro, C.; Calabrò, M.P. COVID-19 and cardiac involvement in childhood: State of the art. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scorrano, G.; David, E.; Calì, E.; Chimenz, R.; La Bella, S.; Di Ludovico, A.; Di Rosa, G.; Gitto, E.; Mankad, K.; Nardello, R.; et al. The Cardiofaciocutaneous Syndrome: From Genetics to Prognostic–Therapeutic Implications. Genes 2023, 14, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceravolo, G.; Zhelcheska, K.; Squadrito, V.; Pellerin, D.; Gitto, E.; Hartley, L.; Houlden, H. Update on leukodystrophies and developing trials. J. Neurol. 2023, 271, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, L.; Sorrentino, F.; Caprari, P.; Taliani, G.; Massimi, S.; Risoluti, R.; Materazzi, S. HCV Infection in Thalassemia Syndromes and Hemoglobinopathies: New Perspectives. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Borrego, A.; Jonas, M.M. Treatment options for hepatitis C infection in children. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 2004, 7, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimenz, R.; Tropeano, A.; Chirico, V.; Ceravolo, G.; Salpietro, C.; Cuppari, C. IL-17 serum level in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis disease. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimben, F.; Peri, F.M.; Impellizzeri, P.; Cardiology, S.I.F.O.P.; Chimenz, R.; Cannavò, L.; Pellegrino, D.; Ceravolo, G.; Calabrò, M.P.; Gitto, E.; et al. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of congenital cardiopathies. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reiter, C.D.; Gladwin, M.T. An emerging role for nitric oxide in sickle cell disease vascular homeostasis and therapy. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2003, 10, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escolar, M.L.; Poe, M.D.; Provenzale, J.M.; Richards, K.C.; Allison, J.; Wood, S.; Wenger, D.A.; Pietryga, D.; Wall, D.; Champagne, M.; et al. Transplantation of Umbilical-Cord Blood in Babies with Infantile Krabbe’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 2069–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarnezhad Tameshkel, F.; Karbalaie Niya, M.H.; Amirkalali, B.; Motamed, N.; Vafaeimanesh, J.; Maadi, M.; Sohrabi, M.; Faraji, A.H.; Khoonsari, M.; Ajdarkosh, H.; et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of Thalassemia Major Patients with Hepatitis C Virus Treated with Sofosbuvir and Daclatasvir: A Cohort Study. Arch. Med. Res. 2022, 53, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzkiewicz, M.; Łoś-Rycharska, E.; Gawryjołek, J.; Gołębiewski, M.; Krogulska, A.; Grzybowski, T. The methylation profile of IL4, IL5, IL10, IFNG and FOXP3 associated with environmental exposures differed between Polish infants with the food allergy and/or atopic dermatitis and without the disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1209190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppari, C.; Amatruda, M.; Ceravolo, G.; Ceravolo, M.D.; Oreto, L.; Colavita, L.; Barbalace, A.; Calabrò, M.P.; Salpietro, C. Myocarditis in children-from infection to autoimmunity. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Loddo, L.; Cutrupi, M.C.; Concolino, D.; De Sarro, R.; Barbalace, A.; Salpietro, A.; Busceti, D.; Ceravolo, M.D.; Calabrò, M.P.; Ceravolo, G.; et al. Cardiac defects in rasopathies: A review of genotype-phenotype correlations. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; To, K.K.W.; Zhang, A.J.X.; Lee, A.C.Y.; Zhu, H.; Mak, W.W.N.; Hung, I.F.N.; Yuen, K.-Y. Co-stimulation With TLR7 Agonist Imiquimod and Inactivated Influenza Virus Particles Promotes Mouse B Cell Activation, Differentiation, and Accelerated Antigen Specific Antibody Production. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramaglia, S.M.C.; Cuppari, C.; Salpietro, C.; Ceravolo, A.; Cutrupi, M.C.; Concolino, D.; De Sarro, R.; Amatruda, M.; Mondello, P.; Ceravolo, G.; et al. Congenital heart disease in Down Syndrome. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Locasciulli, A.; Monguzzi, W.; Tornotti, G.; Bianco, P.; Masera, G. Hepatitis C virus infection and liver disease in children with thalassemia. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1993, 12 (Suppl. S1), 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ceravolo, G.; La Macchia, T.; Cuppari, C.; Dipasquale, V.; Gambadauro, A.; Casto, C.; Ceravolo, M.D.; Cutrupi, M.; Calabrò, M.P.; Borgia, P.; et al. Update on the classification and pathophysiological mechanisms of pediatric cardiorenal syndromes. Children 2021, 8, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Krenger, P.; Krueger, C.C.; Zha, L.; Han, J.; Yermanos, A.; Roongta, S.; Mohsen, M.O.; Oxenius, A.; Vogel, M.; et al. TLR7 Signaling Shapes and Maintains Antibody Diversity Upon Virus-Like Particle Immunization. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 827256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimenz, R.; Cannavò, L.; Gasbarro, A.; Nascimben, F.; Cardiology, S.I.F.O.P.; Sestito, S.; Rizzuti, L.; Ceravolo, G.; Ceravolo, M.D.; Calabrò, M.P.; et al. Pphn and oxidative stress: A review of literature. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ceravolo, G.; Fusco, M.; Salpietro, C.; Concolino, D.; De Sarro, R.; La Macchia, T.; Ceravolo, A.; Oreto, L.; Colavita, L.; Chimenz, R.; et al. Hypertension in childhood. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Meloni, A.; Pistoia, L.; Maffei, S.; Ricchi, P.; Casini, T.; Corigliano, E.; Putti, M.C.; Cuccia, L.; Argento, C.; Positano, V.; et al. Bone status and HCV infection in thalassemia major patients. Bone 2023, 169, 116671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzi, A.; Reis, B.S.; Pereira, P.P.; Pedroso, E.P.; Goes, A.M. Interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 single nucleotide gene polymorphisms in Paracoccidioidomycosis. Cytokine 2009, 48, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.S.; Cheng, G. Role of interleukin 10 transcriptional regulation in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 32, 23–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; He, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Mechanisms of Interleukin-10-Mediated Immunosuppression in Viral Infections. Pathogens 2025, 14, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hakeem, M.S.; Bédard, N.; Murphy, D.; Bruneau, J.; Shoukry, N.H. Signatures of Protective Memory Immune Responses During Hepatitis C Virus Reinfection. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 870–881.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestito, S.; Roppa, K.; Parisi, F.; Moricca, M.T.; Pensabene, L.; Chimenz, R.; Ceravolo, M.D.; Cucinotta, U.; Ceravolo, G.; Calabrò, M.P.; et al. The heart in anderson-fabry disease. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kerkar, N.; Hartjes, K. Hepatitis C Virus–Pediatric and Adult Perspectives in the Current Decade. Pathogens 2024, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, G.; Giannitto, N.; De Luca, F.L.; Salpietro, A.; Cardiology, S.I.F.O.P.; Oreto, L.; Viola, I.; Ceravolo, A.; Nicocia, G.; Sio, A.; et al. Kawasaki disease and cardiac involvement: An update on the state of the art. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, S.; Fan, Y.; Sheng, C.; Ge, W. Association Between IL10 Polymorphisms and the Susceptibility to Sepsis: A Meta-Analysis. Biochem. Genet. 2023, 61, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambadauro, A.; Cucinotta, U.; Galletta, F.; Marseglia, L.; Cannavò, L.; Ceravolo, G.; Damiano, C.; Paino, C.; Marseglia, G.L.; Rulli, I.; et al. A case of myocarditis in a child with Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS-C) related to previous Sars-CoV-2 infection: Our experience. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2022, 36, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Y. Association between IL10 rs1800896 polymorphism and risk of pediatric asthma: A meta-analysis. Clin. Respir. J. 2023, 17, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, E.; Sestito, S.; Lucente, M.; Morrone, A.; Cardiology, S.I.F.O.P.; Zampini, L.; Chimenz, R.; Ceravolo, M.D.; De Sarro, R.; Ceravolo, G.; et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy in mucolipidosis type 2. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Amore, G.; Calì, E.; Spanò, M.; Ceravolo, G.; Mangano, G.D.; Scorrano, G.; Efthymiou, S.; Salpietro, V.; Houlden, H.; Di Rosa, G. ATP6V1B2-related disorders featuring Lennox-Gastaut-syndrome: A case-based overview. Brain Dev. 2023, 45, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolonen, J.P.; Parolin Schnekenberg, R.; McGowan, S.; Sims, D.; McEntagart, M.; Elmslie, F.; Shears, D.; Stewart, H.; Tofaris, G.K.; Dabir, T.; et al. Detailed Analysis of ITPR1 Missense Variants Guides Diagnostics and Therapeutic Design. Mov. Disord. 2024, 39, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.K.; Chan, P.K.S.; Ling, S.C.; Ha, S.Y. Interferon and ribavirin as frontline treatment for chronic hepatitis C infection in thalassaemia major. Br. J. Haematol. 2002, 117, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherker, A.H.; Senosier, M.; Kermack, D. Treatment of transfusion-dependent thalassemic patients infected with hepatitis C virus with interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin. Hepatology 2003, 37, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calì, E.; Lin, S.J.; Rocca, C.; Sahin, Y.; Al Shamsi, A.; El Chehadeh, S.; Chaabouni, M.; Mankad, K.; Galanaki, E.; Efthymiou, S.; et al. A homozygous MED11 C-terminal variant causes a lethal neurodegenerative disease. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 2194–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, A.; Gambadauro, A.; Dipasquale, V.; Casto, C.; Ceravolo, M.D.; Accogli, A.; Scala, M.; Ceravolo, G.; Iacomino, M.; Zara, F.; et al. Biallelic variants in kif17 associated with microphthalmia and coloboma spectrum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | N | Mean Age (Years) | M:F Ratio | Mean IgE (IU/mL) | Comparison (HCV+ vs. HCV−) | Allergy Symptoms (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV-positive BT | 37 | 10.1 ± 3.2 | 21:16 | 18.73 ± 4.2 | p < 0.001 | 21.6% |

| HCV-negative BT | 9 | 9.8 ± 3.0 | 5:4 | 118.76 ± 7.9 | 55.5% | |

| Healthy controls | 50 | 10.5 ± 2.9 | 24:21 | 16.84 ± 5.4 | p < 0.05 (vs. both BT groups) | 22.2% |

| SNP | Genotype | HCV-Positive (n = 37) | HCV-Negative (n = 9) | Atopy Prevalence (%) | Comparison (HCV+ vs. HCV−) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL10 −1082 | AA | 23 (62.2%) | 3 (33.3%) | 13.0% (HCV+) vs. 66.7% (HCV−) | AA higher in HCV+, lower atopy |

| IL10 −1082 | AG/GG | 14 (37.8%) | 6 (66.7%) | 21.4% (HCV+) vs. 33.3% (HCV−) | AG/GG more frequent in HCV− |

| TLR7 rs179008 | TT | 19 (51.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 10.5% (HCV+) vs. 50.0% (HCV−) | TT enriched in HCV+, lower atopy |

| TLR7 rs179008 | CT/CC | 18 (48.6%) | 7 (77.8%) | 22.2% (HCV+) vs. 28.6% (HCV−) | CT/CC more frequent in HCV− |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuppari, C.; Mancuso, A.; Colavita, L.; Cusmano, C.; Tallarico, V.; Caruso, V.; Chimenz, R.; Caloiero, M.; Calafiore, M.; La Mazza, A.; et al. Host Immunogenetics and Chronic HCV Infection Shape Atopic Risk in Pediatric Beta-Thalassemia: A Genotype–Phenotype Study. Genes 2025, 16, 1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121440

Cuppari C, Mancuso A, Colavita L, Cusmano C, Tallarico V, Caruso V, Chimenz R, Caloiero M, Calafiore M, La Mazza A, et al. Host Immunogenetics and Chronic HCV Infection Shape Atopic Risk in Pediatric Beta-Thalassemia: A Genotype–Phenotype Study. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121440

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuppari, Caterina, Alessio Mancuso, Laura Colavita, Clelia Cusmano, Valeria Tallarico, Valerio Caruso, Roberto Chimenz, Mimma Caloiero, Mariarosa Calafiore, Antonina La Mazza, and et al. 2025. "Host Immunogenetics and Chronic HCV Infection Shape Atopic Risk in Pediatric Beta-Thalassemia: A Genotype–Phenotype Study" Genes 16, no. 12: 1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121440

APA StyleCuppari, C., Mancuso, A., Colavita, L., Cusmano, C., Tallarico, V., Caruso, V., Chimenz, R., Caloiero, M., Calafiore, M., La Mazza, A., & Rigoli, L. (2025). Host Immunogenetics and Chronic HCV Infection Shape Atopic Risk in Pediatric Beta-Thalassemia: A Genotype–Phenotype Study. Genes, 16(12), 1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121440