The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Encyclia tampensis (Orchidaceae): Structural Variation and Heterogeneous Evolutionary Dynamics in Epidendreae

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, DNA Extraction, and Quality Assessment

2.2. Genome Sequencing and Plastome Assembly

2.3. Plastome Annotation and Visualization

2.4. Data Curation and Comparative Dataset Assembly

2.5. Analysis of Relative Synonymous Codon Usage

2.6. Neutrality Analysis and Evolutionary Forces

2.7. Analysis of Codon Usage Bias Using ENC–GC3 Plots

2.8. Parity Rule 2 (PR2) Plot Analysis

2.9. Multivariate Analysis of Codon Usage Patterns

2.10. Identification and Characterization of Chloroplast Simple Sequence Repeats

2.11. Analysis of Evolutionary Selection Pressures (Ka/Ks)

2.12. Genome Structure and Synteny Analysis

2.13. Phylogenetic Reconstruction Using Plastomes

3. Results

3.1. Plastome Assembly, Structure and Characteristics of Epidendreae

3.2. RSCU Analysis

3.3. SSR Analysis

3.4. ENC-GC3 Analysis

3.5. Neutrality Analysis

3.6. PR2 Bias Analysis

3.7. COA

3.8. Ka/Ks Analysis

3.9. Collinearity Analysis

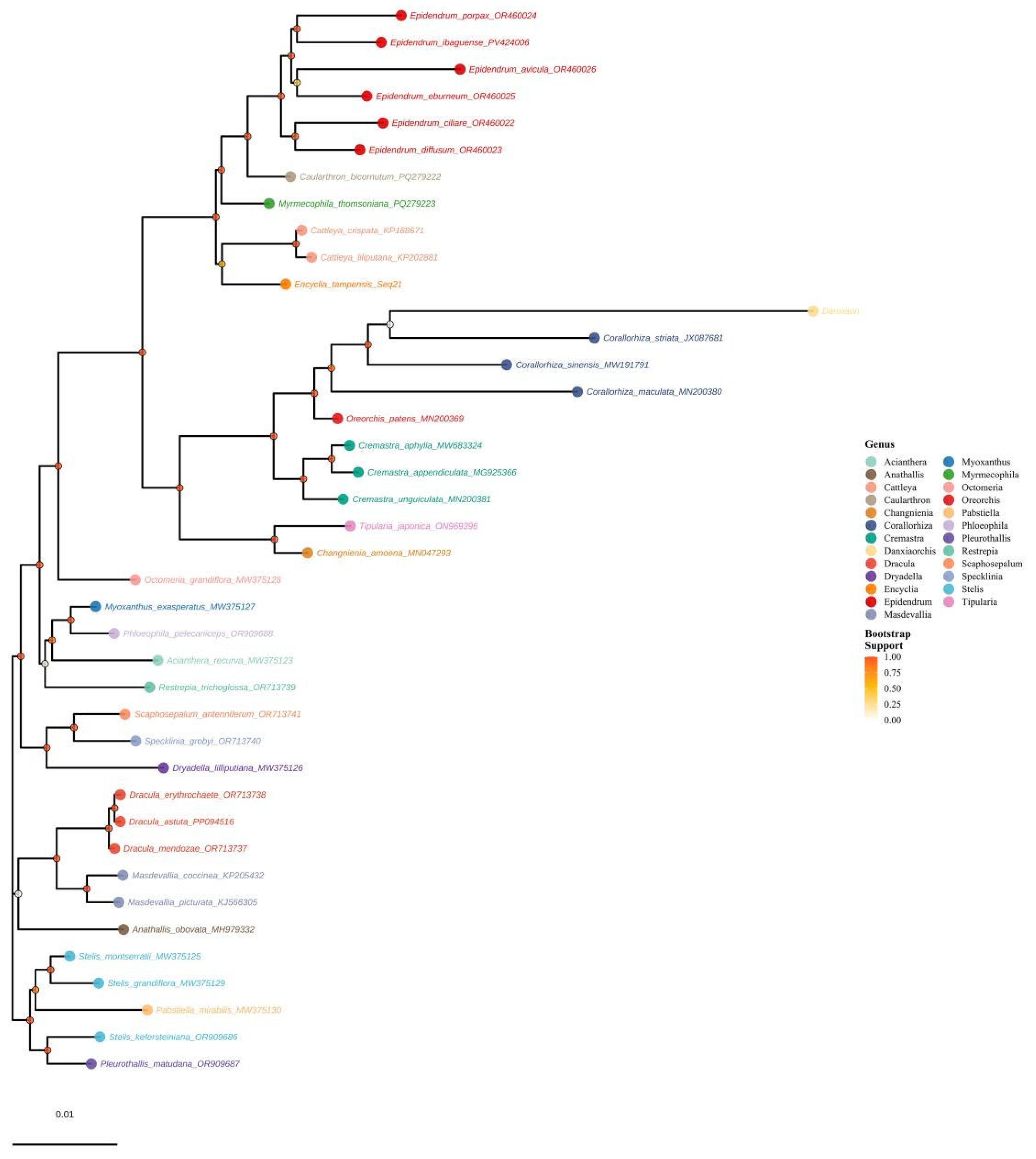

3.10. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Plastid Genome Structural Characteristics and Evolutionary Dynamics

4.2. Codon Usage Patterns and Evolutionary Drivers

4.3. Phylogenetic Significance and Taxonomic Implications

4.4. Conservation Genetics Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phillips, R.D.; Reiter, N.; Peakall, R. Orchid conservation: From theory to practice. Ann. Bot. 2020, 126, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-T. Orchid Biochemistry; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Naive, M.A.K.; Handoyo, F.; Ormerod, P.; Champion, J. Dendrobium niveolabium (Crchidaceae, section Grastidium), a new dendrobiinae species from papua, indonesia. Phytotaxa 2021, 490, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, E.R.S.; Nugroho, A.S.; Ulfah, M. Types of epiphytic orchids and host plants on ungaran mountain limbangan kendal central java and its potential as orchid conservation area. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2020, 11, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, M.E.; Woods, C.L. A case for studying biotic interactions in epiphyte ecology and evolution. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2022, 54, 125658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hu, Y.; Huang, M.Z.; Huang, W.C.; Liu, D.K.; Zhang, D.; Hu, H.; Downing, J.L.; Liu, Z.J.; Ma, H. Comprehensive phylogenetic analyses of Orchidaceae using nuclear genes and evolutionary insights into epiphytism. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1204–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, C.; Goldman, D.H.; Freudenstein, J.V.; Pridgeon, A.M.; Cameron, K.M.; Chase, M.W. An overview of the phylogenetic relationships within Epidendroideae inferred from multiple DNA regions and recircumscription of Epidendreae and Arethuseae (Orchidaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2005, 92, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, A.H. Phylogeny and Evolution of Mycorrhizal Associations in the Myco-Heterotrophic Hexalectris Raf.(Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae). Ph.D. Thesis, Miami University, Oxford, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, G.H.; Koroleva, O.Y.; Dalling, J.W.; Winter, K. Acclimation of tropical tree seedlings to excessive light in simulated tree--fall gaps. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravendeel, B.; Smithson, A.; Slik, F.J.; Schuiteman, A. Epiphytism and pollinator specialization: Drivers for orchid diversity? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunth, K.S. Considérations Générales sur les Graminées; éditeur non identifié; 1815. [Google Scholar]

- Bentham, G.; Hooker, J. Genera Plantarum (Orchidaceae); Reeve, Co Edition: London, UK, 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Schlechter, R. Das system der orchidaceen. Notizbl. Des königl. Bot. Gart. Und Mus. Zu Berl. 1926, 88, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, R.L. The relationships of meiracyllium (Orchidaceae). Brittonia 1960, 12, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, R.L. Phylogeny and Classification of the Orchid Family; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Szlachetko, D. Systema Orchidalium: Fragmenta Floristica et Geobotanica, Suppl. 3; W Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences: Krakow, Poland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Neyland, R.; Urbatsch, L.E. Phylogeny of subfamily Epidendroideae (Orchidaceae) inferred from ndhF chloroplast gene sequences. Am. J. Bot. 1996, 83, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenstein, J.V.; Rasmussen, F.N. What does morphology tell us about orchid relationships?—A cladistic analysis. Am. J. Bot. 1999, 86, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, K.M.; Chase, M.W.; Whitten, W.M.; Kores, P.J.; Jarrell, D.C.; Albert, V.A.; Yukawa, T.; Hills, H.G.; Goldman, D.H. A phylogenetic analysis of the Orchidaceae: Evidence from rbcL nucleotide sequences. Am. J. Bot. 1999, 86, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenstein, J.V.; Senyo, D.M.; Chase, M.W. Mitochondrial DNA and relationships in the Orchidaceae. In Monocots: Systematics and Evolution: Systematics and Evolution; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2000; 421p. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Berg, C. Molecular Phylogenetics of Tribe Epidendreae with Emphasis on Subtribe Laeliinae (Orchidaceae). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, C. Phylogeny and systematics of Cattleya and Sophronitis. In Proceedings of the 19th World Orchid Conference Miami: American Printing Arts, Miami, FL, USA, 23–27 January 2008; pp. 319–323. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, R.L.; Pollard, G.E. The Genus Encyclia in Mexico; Asociación Mexicana de Orquideología: Comala, Mexico, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Leopardi-Verde, C.L.; Carnevali, G.; Romero-González, G.A. A phylogeny of the genus Encyclia (Orchidaceae: Laeliinae), with emphasis on the species of the Northern Hemisphere. J. Syst. Evol. 2017, 55, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipińska, M.M.; Olędrzyńska, N.; Dudek, M.; Naczk, A.M.; Łuszczek, D.; Szabó, P.; Speckmaier, M.; Szlachetko, D.L. Characters evolution of Encyclia (Laeliinae-Orchidaceae) reveals a complex pattern not phylogenetically determined: Insights from macro-and micromorphology. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevali, G.; Tamayo-Cen, I.; Mendez-Luna, C.E.; Ramírez--Morillo, I.M.; Tapia-Munoz, J.L.; Cetzal-Ix, W.; Romero-Gonzalez, G.A. Phylogenetics and historical biogeography of Encyclia (Laeliinae: Orchidaceae) with an emphasis on the E. adenocarpos complex, a new species, and a preliminary species list for the genus. Org. Divers. Evol. 2023, 23, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, J. Epidendrum odoratissimum. In Edwards’s Botanical Register; James Ridgway: London, UK, 1831. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, J. Folia orchidacea. Epidendrum, 1853. [Google Scholar]

- Schlechter, F.; Schlechter, R. Encyclia Hook. In Schlechter, R, Die Orchideen; Paul Parey: Berlin, Germany, 1914; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, R.L. A reconsideration of Encyclia (Orchidaceae). Brittonia 1961, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withner, C.L. The Bahamian and Caribbean Species; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, W.E.; van den Berg, C.; Whitten, W.M. A combined molecular phylogeny of Encyclia (Orchidaceae) and relationships within Laeliinae. Selbyana 2003, 24, 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Pupulin, F.; Bogarin, D. A taxonomic revision of Encyclia (Orchidaceae: Laeliinae) in Costa Rica. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2012, 168, 395–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, T.L.; Salazar, G.A.; van den Berg, C. Phylogeny of Prosthechea (Laeliinae, Orchidaceae) based on nrITS and plastid DNA sequences: Reassessing the lumper--splitter debate and shedding light on the evolution of this Neotropical genus. Taxon 2024, 73, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, V.P.; Pessoa, E.M.; Demarchi, L.O.; Sader, M.; Fernandez Piedade, M.T. Encyclia, Epidendrum, or Prosthechea? Clar-ifying the phylogenetic position of a rare Amazonian orchid (Laeliinae-Epidendroideae-Orchidaceae). Syst. Bot. 2019, 44, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, W.E. Intergeneric and Intrageneric Phylogenetic Relationships of Encyclia (Orchidaceae) Based upon Holomor-Phology. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pupulin, F.; Bogarín, D. Of greenish Encyclia: Natural variation, taxonomy, cleistogamy, and a comment on DNA barcoding. Lankesteriana Int. J. Orchid. 2011, 11, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, G.I. Chloroplast origin and integration. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.S. Chloroplast genetic engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gügel, I.L.; Soll, J. Chloroplast differentiation in the growing leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. Protoplasma 2017, 254, 1857–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, M.T.; Zurawski, G. Chloroplast DNA and the study of plant phylogeny: Present status and future prospects. In Molecular Systematics of Plants; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.; Liu, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, S. Highly variable chloroplast markers for evaluating plant phylogeny at low taxonomic levels and for DNA barcoding. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zeng, M.-Y.; Wu, Y.-W.; Li, J.-W.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z.-J.; Li, M.-H. Characterization and comparative analysis of the complete plastomes of five Epidendrum (Epidendreae, Orchidaceae) species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weremijewicz, J.; Almonte, J.I.; Hilaire, V.S.; Lopez, F.D.; Lu, S.H.; Marrero, S.M.; Martinez, C.M.; Zarate, E.A.; Lam, A.K.; Ferguson, S.A.N.; et al. Microsatellite primers for two threatened orchids in Florida: Encyclia tampensis and Cyrtopodium punctatum (Orchidaceae). Appl. Plant Sci. 2016, 4, 1500095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, H.; Cao, Y.; Ma, G.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, H.; Song, X.; Sui, S. Reducing costs and shortening the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method to improve DNA extraction efficiency from wintersweet and some other plants. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Latif, A.; Osman, G. Comparison of three genomic DNA extraction methods to obtain high DNA quality from maize. Plant Methods 2017, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brena, R.M.; Auer, H.; Kornacker, K.; Hackanson, B.; Raval, A.; Byrd, J.C.; Plass, C. Accurate quantification of DNA methylation using combined bisulfite restriction analysis coupled with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Foox, J.; Tighe, S.W.; Nicolet, C.M.; Zook, J.M.; Byrska-Bishop, M.; Clarke, W.E.; Khayat, M.M.; Mahmoud, M.; Laaguiby, P.K.; Herbert, Z.T. Performance assessment of DNA sequencing platforms in the ABRF Next-Generation Sequencing Study. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.-J.; Yu, W.-B.; Yang, J.-B.; Song, Y.; DePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.-S.; Li, D.-Z. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillich, M.; Lehwark, P.; Pellizzer, T.; Ulbricht-Jones, E.S.; Fischer, A.; Bock, R.; Greiner, S. GeSeq–versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ni, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, C. CPGView: A package for visualizing detailed chloroplast genome structures. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2023, 23, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.M.; Tuohy, T.M.; Mosurski, K.R. Codon usage in yeast: Cluster analysis clearly differentiates highly and lowly expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986, 14, 5125–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueoka, N. Intrastrand parity rules of DNA base composition and usage biases of synonymous codons. J. Mol. Evol. 1995, 40, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, F. The ‘effective number of codons’ used in a gene. Gene 1990, 87, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueoka, N. Near homogeneity of PR2-bias fingerprints in the human genome and their implications in phylogenetic analyses. J. Mol. Evol. 2001, 53, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-C.; Hickey, D.A. Rapid divergence of codon usage patterns within the rice genome. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, S.; Thiel, T.; Münch, T.; Scholz, U.; Mascher, M. MISA-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2583–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, L.; Roat Kultima, J.; Andersson, S.G. genoPlotR: Comparative gene and genome visualization in R. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2334–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-Y.; Yang, J.-X.; Bai, M.-Z.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Liu, Z.-J. The chloroplast genome evolution of Venus slipper (Paphiopedilum): IR expansion, SSC contraction, and highly rearranged SSC regions. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicke, S.; Schneeweiss, G.M.; Depamphilis, C.W.; Müller, K.F.; Quandt, D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: Gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011, 76, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswari, P.; Kunhikannan, C.; Yasodha, R. Chloroplast genome analysis of Angiosperms and phylogenetic relationships among Lamiaceae members with particular reference to teak (Tectona grandis L.f). bioRxiv 2020, 46, 078212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tong, Y.; Xing, F. DNA barcoding evaluation and its taxonomic implications in the recently evolved genus Oberonia Lindl.(Orchidaceae) in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givnish, T.J.; Spalink, D.; Ames, M.; Lyon, S.P.; Hunter, S.J.; Zuluaga, A.; Iles, W.J.; Clements, M.A.; Arroyo, M.T.; Leebens-Mack, J. Orchid phylogenomics and multiple drivers of their extraordinary diversification. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20151553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Qin, Y.; Shao, B.; Li, J.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, B.; Jin, X. The extremely reduced, diverged and reconfigured plastomes of the largest mycoheterotrophic orchid lineage. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, C.; Xu, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z. Comparative analysis of codon bias in the chloroplast genomes of theaceae species. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 824610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gong, W.; Li, Y. Comparative analysis of the codon usage pattern in the chloroplast genomes of Gnetales species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knill, T.; Reichelt, M.; Paetz, C.; Gershenzon, J.; Binder, S. Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a bacterial-type heterodimeric isopropylmalate isomerase involved in both Leu biosynthesis and the Met chain elongation pathway of glucosinolate formation. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 71, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapralov, M.V.; Filatov, D.A. Widespread positive selection in the photosynthetic Rubisco enzyme. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.-Y.; Lin, W.-J.; Li, R.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.-J.; Li, M.-H. Characterization of Angraecum (Angraecinae, Orchidaceae) plastomes and utility of sequence variability hotspots. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Nie, L.; Deng, S.; Duan, L.; Wang, Z.; Charboneau, J.L.; Ho, B.C.; Chen, H. Characterization of Firmiana danxiaensis plastomes and comparative analysis of Firmiana: Insight into its phylogeny and evolution. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, M.W.; Cameron, K.M.; Freudenstein, J.V.; Pridgeon, A.M.; Salazar, G.; Van den Berg, C.; Schuiteman, A. An updated classification of Orchidaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 177, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-Y.; Liao, M.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Feng, Y.; Ju, W.-B.; Deng, H.-N.; Li, X.; Plenković-Moraj, A.; Xu, B. Comparative chloroplast genomics of seven endangered Cypripedium species and phylogenetic relationships of Orchidaceae. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 911702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Jo, S.; Cheon, S.-H.; Joo, M.-J.; Hong, J.-R.; Kwak, M.; Kim, K.-J. Plastome evolution and phylogeny of Orchidaceae, with 24 new sequences. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-K.; Tu, X.-D.; Zhao, Z.; Zeng, M.-Y.; Zhang, S.; Ma, L.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Wang, M.-M.; Liu, Z.-J.; Lan, S.-R. Plastid phylogenomic data yield new and robust insights into the phylogeny of Cleisostoma–Gastrochilus clades (Orchidaceae, Aeridinae). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2020, 145, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Sharma, J. Efficiency of microsatellite isolation from orchids via next-generation sequencing. PeerJ 2012, 2, e4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, B.; Huang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Yuan, Z.; Yao, Y. The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Encyclia tampensis (Orchidaceae): Structural Variation and Heterogeneous Evolutionary Dynamics in Epidendreae. Genes 2025, 16, 1418. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121418

Liu B, Huang J, Wang Z, Li D, Yuan Z, Yao Y. The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Encyclia tampensis (Orchidaceae): Structural Variation and Heterogeneous Evolutionary Dynamics in Epidendreae. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1418. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121418

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Bing, Ju Huang, Zishuo Wang, Dong Li, Zhangxi Yuan, and Yi Yao. 2025. "The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Encyclia tampensis (Orchidaceae): Structural Variation and Heterogeneous Evolutionary Dynamics in Epidendreae" Genes 16, no. 12: 1418. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121418

APA StyleLiu, B., Huang, J., Wang, Z., Li, D., Yuan, Z., & Yao, Y. (2025). The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Encyclia tampensis (Orchidaceae): Structural Variation and Heterogeneous Evolutionary Dynamics in Epidendreae. Genes, 16(12), 1418. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121418