Identification of Exercise-Related Signature Genes Potentially Associated with Cocaine Addiction by Integrating Bioinformatics and Mendelian Randomization Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Identification of Exercise-Related Differentially Expressed Genes

2.3. Protein Interaction Networks and Principal Component Analysis of Exercise-Related Differential Genes

2.4. Functional and Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Exercise-Related DEGs

2.5. Immunoinfiltration Analysis of DEGs

2.6. Identification of Signature Genes from Exercise-Related DEGs

2.7. GSEA Enrichment Analysis of Signature Genes

2.8. Mendelian Randomization Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of DEGs Between the Cocaine Addiction and Control Group

3.2. PPI Network Construction, Correlation and Functional Enrichment Analysis of Exercise-Related DEGs

3.3. Immunological Characterization of Cocaine Addiction and Exercise-Related DEGs

3.4. Identification and Characterization of Exercise-Related Signature Genes

3.5. The Value of Exercise-Related Signature Genes in the Diagnosis of Cocaine Addiction

3.6. Functional Analysis of Exercise-Related Signature Genes and Correlation Analysis of Immune Infiltration

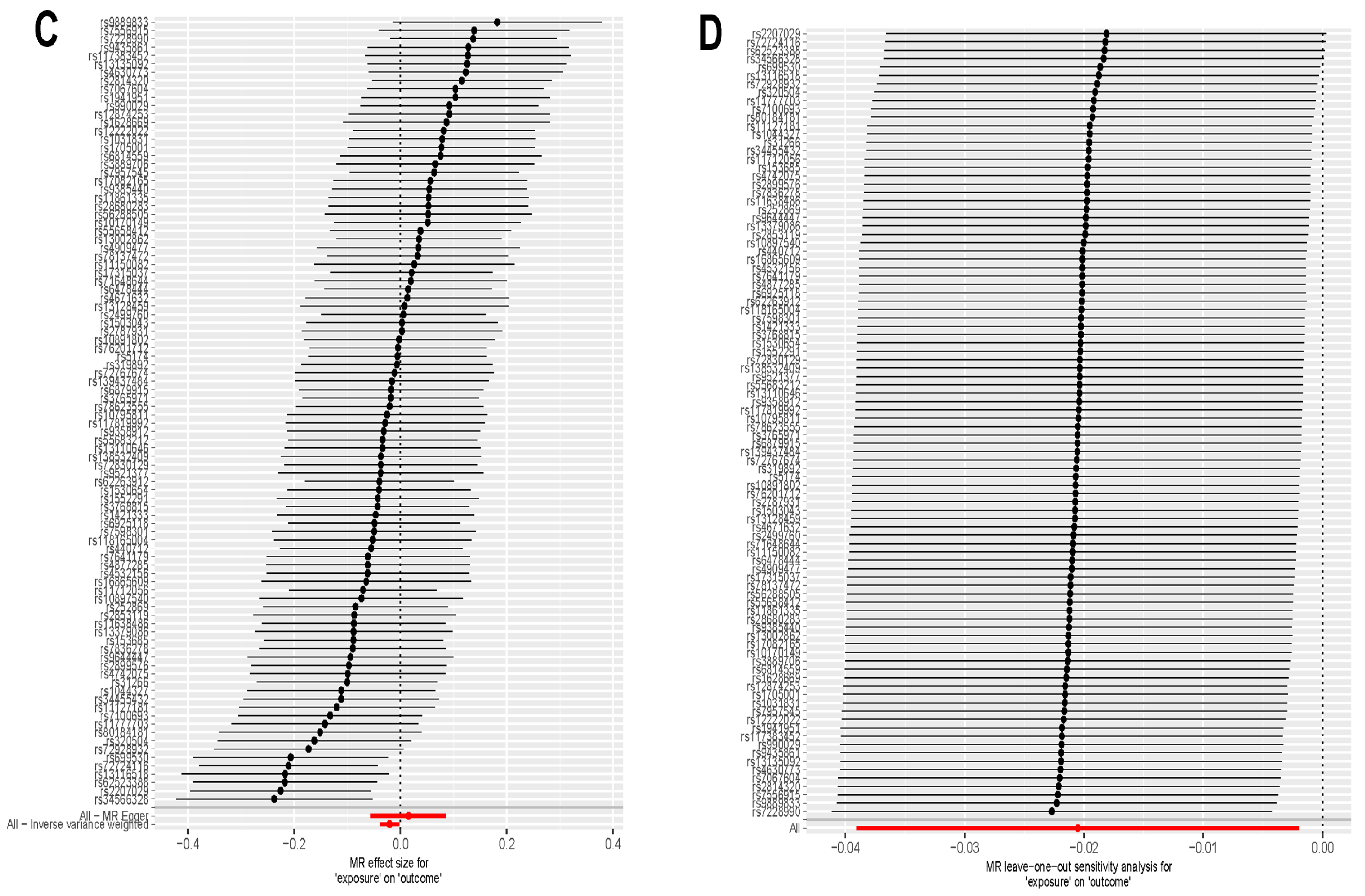

3.7. Directional Correlation Analysis Between Exercise and Addiction

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ross, S.; Peselow, E. The neurobiology of addictive disorders. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2009, 32, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, K.; Zhu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Gao, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L. Exercise regulates the metabolic homeostasis of methamphetamine dependence. Metabolites 2022, 12, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, S.; Chen, H.; Yun, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Lv, J.; He, Y.; Li, W. Identification of key genes and therapeutic drugs for cocaine addiction using integrated bioinformatics analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1201897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreek, M.J.; Levran, O.; Reed, B.; Schlussman, S.D.; Zhou, Y.; Butelman, E.R. Opiate addiction and cocaine addiction: Underlying molecular neurobiology and genetics. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 3387–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Castillo, N.; Cabana-Dominguez, J.; Corominas, R.; Cormand, B. Molecular genetics of cocaine use disorders in humans. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, R.C.; Fant, B.; Swinford-Jackson, S.E.; Heller, E.A.; Berrettini, W.H.; Wimmer, M.E. Environmental, genetic and epigenetic contributions to cocaine addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Liang, X.; Huang, Q.; Zheng, T.; Li, X. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on social health and physical and mental health of methamphetamine-dependent individuals: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 997960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.A.; Fronk, G.E.; Abel, J.M.; Lacy, R.T.; Bills, S.E.; Lynch, W.J. Resistance exercise decreases heroin self-administration and alters gene expression in the nucleus accumbens of heroin-exposed rats. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, W.J.; Peterson, A.B.; Sanchez, V.; Abel, J.; Smith, M.A. Exercise as a novel treatment for drug addiction: A neurobiological and stage-dependent hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 1622–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batatinha, H.; Lira, F.; Kruger, K.; Rosa Neto, J. Physical exercise and metabolic reprogramming. In Essential Aspects of Immunometabolism in Health and Disease; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Guida, C.R.; Maia, J.M.; Ferreira, L.F.R.; Rahdar, A.; Branco, L.G.; Soriano, R.N. Advancements in addressing drug dependence: A review of promising therapeutic strategies and interventions. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 134, 111070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, C.; Li, R. Sex differences in drug addiction and response to exercise intervention: From human to animal studies. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2016, 40, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.-G.; Gan, Y.; Fu, Y.; Shi, H.; Dai, S.; Yu, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Wang, F.; Yuan, T.-F. Treadmill exercise training inhibits morphine CPP by reversing morphine effects on GABA neurotransmission in D2-MSNs of the accumbens-pallidal pathway in male mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 49, 1700–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.; Hanna, C.; Sajjad, M.; Yao, R.; Blum, K.; Gold, M.S.; Quattrin, T.; Thanos, P.K. Exercise Influences the Brain’s Metabolic Response to Chronic Cocaine Exposure in Male Rats. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Guglielmo, G.; Carrette, L.; Kallupi, M.; Brennan, M.; Boomhower, B.; Maturin, L.; Conlisk, D.; Sedighim, S.; Tieu, L.; Fannon, M.J. Large-scale characterization of cocaine addiction-like behaviors reveals that escalation of intake, aversion-resistant responding, and breaking-points are highly correlated measures of the same construct. eLife 2024, 12, RP90422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Jia, S.; Wang, P.; Liu, C.; Li, Y. Effect of exercise on cravings levels in individuals with drug dependency: A systematic review. Addict. Behav. 2024, 158, 108127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Zhou, C. Impact of physical exercise on substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, S.E.; Ussher, M. Exercise-based treatments for substance use disorders: Evidence, theory, and practicality. Am. J. Drug Alcohol. Abus. 2015, 41, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, M.F. The role of bioinformatics in molecular biology: Tools and techniques for data analysis. Multidiscip. J. Biochem. 2024, 1, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, Z.E.; Wootton, R.E.; Munafò, M.R. Using Mendelian randomization to explore the gateway hypothesis: Possible causal effects of smoking initiation and alcohol consumption on substance use outcomes. Addiction 2022, 117, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, R. Transforming clinical research: The power of high-throughput omics integration. Proteomes 2024, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranstam, J.; Cook, J.A. LASSO regression. J. Br. Surg. 2018, 105, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigatti, S.J. Random forest. J. Insur. Med. 2017, 47, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saika, F.; Kiguchi, N.; Wakida, N.; Kobayashi, D.; Fukazawa, Y.; Matsuzaki, S.; Kishioka, S. Upregulation of CCL7 and CCL2 in reward system mediated through dopamine D1 receptor signaling underlies methamphetamine-induced place preference in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 665, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Li, Z.; Ma, S.; Luo, J.; Xu, S.; Lu, A.; Gan, W.; Su, P.; Lin, H.; Li, S. Heroin activates Bim via c-Jun N-terminal kinase/c-Jun pathway to mediate neuronal apoptosis. Neuroscience 2013, 233, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasakul, S.; Watiktinkorn, P.; Thanoi, S.; Dalton, C.F.; Fachim, H.A.; Nudmamud-Thanoi, S.; Reynolds, G.P. Increased DNA methylation in the parvalbumin gene promoter is associated with methamphetamine dependence. Pharmacogenomics 2017, 18, 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, H.; Ji, J.; Zhang, R.; Dang, W.; Xie, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J. Expression quantitative trait locus rs6356 is associated with susceptibility to heroin addiction by potentially influencing TH gene expression in the Hippocampus and nucleus Accumbens. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 72, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; Cho, J. Role of chemokine CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 in neurodegenerative diseases. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2013, 36, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beitner-Johnson, D.; Nestler, E.J. Morphine and cocaine exert common chronic actions on tyrosine hydroxylase in dopaminergic brain reward regions. J. Neurochem. 1991, 57, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-M.; Hamza, M.; Wu, T.-X.; Dionne, R.A. Upregulation of IL-6, IL-8 and CCL2 gene expression after acute inflammation: Correlation to clinical pain. Pain® 2009, 142, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.; Peng, Q.; Xie, Z.; Chen, F.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, C. Integration of molecular inflammatory interactome analyses reveals dynamics of circulating cytokines and extracellular vesicle long non-coding RNAs and mRNAs in heroin addicts during acute and protracted withdrawal. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 730300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Sun, Y.; Zan, G.; Zhao, M. The interaction between central and peripheral immune systems in methamphetamine use disorder: Current status and future directions. J. Neuroinflamm. 2025, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Elnazar, S.; Moaaz, M.; Ghoneim, H.; Molokhia, T.; El-Korany, W. Th17/Treg imbalance in opioids and cannabinoids addiction: Relationship to NF-κB activation in CD4+ T cells. Egypt. J. Immunol. 2014, 21, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, C.E.; Daugherity, E.K.; Rogers, A.B.; Abi Abdallah, D.S.; Denkers, E.Y.; Maurer, K.J. CCR2 and CD44 promote inflammatory cell recruitment during fatty liver formation in a lithogenic diet fed mouse model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebur, N.A.; Enad, M.A.; Awad, A.S. HSP70 Levels as New Metabolic Marker for the Early Detection and Diagnosis of Stroke in Patients with Cocaine Addiction. Sch. Int. J. Biochem. 2025, 8, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Marchena, N.; Barrera, M.; Mestre-Pintó, J.I.; Araos, P.; Serrano, A.; Pérez-Mañá, C.; Papaseit, E.; Fonseca, F.; Ruiz, J.J.; Rodríguez de Fonseca, F. Inflammatory mediators and dual depression: Potential biomarkers in plasma of primary and substance-induced major depression in cocaine and alcohol use disorders. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, Q.; Su, H.; Chen, T.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Shi, S.; Du, J.; Jiang, H. Peripheral Blood Exosomal miR-184-3p in Methamphetamine Use Disorder: Biomarker Potential and CRTC1-Mediated Neuroadaptation. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-X.; Wang, X.-Q.; Haghparast, A.; He, W.-B.; Zhang, J.-J. Advances in the study of the role of chemokines in drug addiction and the potential effects of traditional Chinese medicines. Brain Behav. Immun. Integr. 2023, 4, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskiewicz, D.E.; Uhl, G.R.; Hall, F.S. The role of cell adhesion molecule genes regulating neuroplasticity in addiction. Neural Plast. 2018, 2018, 9803764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Meseguer, J.; Tortosa-Martínez, J.; Cortell-Tormo, J.M. The benefits of physical exercise on mental disorders and quality of life in substance use disorders patients. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschucke, E.; Heinz, A.; Ströhle, A. Exercise and physical activity in the therapy of substance use disorders. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 901741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, S.; Dudbridge, F.; Thompson, S.G. Combining information on multiple instrumental variables in Mendelian randomization: Comparison of allele score and summarized data methods. Stat. Med. 2016, 35, 1880–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.; Walia, G.; Sachdeva, M. ‘Mendelian randomization’: An approach for exploring causal relations in epidemiology. Public Health 2017, 145, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Symbol | logFC | Change | AveExpr | t | p. Value | adj. P.Val | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVALB | −0.9040713 | Down | 10.9340726 | −4.117985 | 0.00011699 | 0.01874068 | 1.08834444 |

| TH | −0.6655347 | Down | 13.6742803 | −3.459475 | 0.00099407 | 0.04754572 | −0.8169993 |

| CKMT1B | −0.5378571 | Down | 9.42642172 | −2.7112424 | 0.00869799 | 0.12918337 | −2.7085261 |

| ALDH1A1 | −0.5257757 | Down | 13.2106844 | −2.5519271 | 0.01323805 | 0.16193745 | −3.0666404 |

| GLS | −0.4003609 | Down | 11.7096645 | −2.1415717 | 0.03623662 | 0.26471224 | −3.9074687 |

| NTS | −0.3989501 | Down | 7.53491886 | −2.222223 | 0.02999247 | 0.24193402 | −3.7518751 |

| ACOT7 | −0.392685 | Down | 11.0059734 | −2.9431282 | 0.00459224 | 0.09452388 | −2.1578242 |

| CALM3 | −0.3877455 | Down | 13.9020062 | −3.1237466 | 0.00273296 | 0.07349115 | −1.7059998 |

| CBS | 0.40987253 | UP | 9.82353997 | 3.24744315 | 0.00189576 | 0.06206236 | −1.3856415 |

| MCL1 | 0.43759294 | UP | 8.63790681 | 5.51343691 | 7.57 × 10−7 | 0.00218308 | 5.63078405 |

| EDN1 | 0.44110921 | UP | 8.47453027 | 2.54220771 | 0.01357469 | 0.16452647 | −3.0879343 |

| PNP | 0.44485248 | UP | 8.61166132 | 3.12815678 | 0.00269794 | 0.0732806 | −1.6947275 |

| CLIC1 | 0.45165804 | UP | 9.52609315 | 5.13521173 | 3.13 × 10−6 | 0.00371219 | 4.34961648 |

| CD44 | 0.45530446 | UP | 9.96710693 | 4.43777402 | 3.88 × 10−5 | 0.01210736 | 2.07828665 |

| IL1B | 0.48791033 | UP | 7.7498335 | 2.31589396 | 0.02394641 | 0.21959765 | −3.5651186 |

| VCAM1 | 0.54219228 | UP | 8.73761938 | 5.52828584 | 7.16 × 10−7 | 0.00218308 | 5.68163473 |

| IL6 | 0.55541545 | UP | 7.47143369 | 2.67218286 | 0.00965536 | 0.13676059 | −2.7978899 |

| S100A9 | 0.57873832 | UP | 7.81671457 | 3.01240385 | 0.00377152 | 0.08619948 | −1.986824 |

| HSPB1 | 0.59167695 | UP | 12.1919345 | 3.47923393 | 0.00093495 | 0.04626419 | −0.7628044 |

| CXCL8 | 0.77885885 | UP | 7.73964873 | 2.98477665 | 0.00408093 | 0.08967083 | −2.0553665 |

| S100A8 | 0.80605271 | UP | 8.18308567 | 2.7360823 | 0.00813521 | 0.12530676 | −2.6511752 |

| BAG3 | 0.816936 | UP | 10.9550748 | 3.85386002 | 0.00028235 | 0.02710923 | 0.30076053 |

| JUN | 0.84145631 | UP | 10.6533235 | 4.41005037 | 4.28 × 10−5 | 0.01216747 | 1.99101944 |

| SERPINH1 | 0.84327308 | UP | 8.45667748 | 3.33088725 | 0.00147448 | 0.05604694 | −1.1647255 |

| HSPA1A | 0.86890436 | UP | 12.028583 | 3.22907177 | 0.00200263 | 0.06350456 | −1.4337653 |

| CDKN1A | 1.02758502 | UP | 8.71041932 | 4.81688536 | 1.00 × 10−5 | 0.00669562 | 3.29612798 |

| CCL2 | 1.09239267 | UP | 8.6513175 | 5.01330203 | 4.90 × 10−6 | 0.00494924 | 3.94318854 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, J.; Deng, X.; Deng, Y.; Huang, X. Identification of Exercise-Related Signature Genes Potentially Associated with Cocaine Addiction by Integrating Bioinformatics and Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Genes 2025, 16, 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121414

He J, Deng X, Deng Y, Huang X. Identification of Exercise-Related Signature Genes Potentially Associated with Cocaine Addiction by Integrating Bioinformatics and Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121414

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Jinke, Xiaoyu Deng, Yuxuan Deng, and Xiao Huang. 2025. "Identification of Exercise-Related Signature Genes Potentially Associated with Cocaine Addiction by Integrating Bioinformatics and Mendelian Randomization Analysis" Genes 16, no. 12: 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121414

APA StyleHe, J., Deng, X., Deng, Y., & Huang, X. (2025). Identification of Exercise-Related Signature Genes Potentially Associated with Cocaine Addiction by Integrating Bioinformatics and Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Genes, 16(12), 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121414