A Plot Twist: When RNA Yields Unexpected Findings in Paired DNA-RNA Germline Genetic Testing

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Testing Cohort

2.2. CaptureSeq RNA Testing and RT-PCRseq

3. Results

3.1. Canonical Variant with No Abnormal Splicing

3.2. Pseudo-Intron Creation

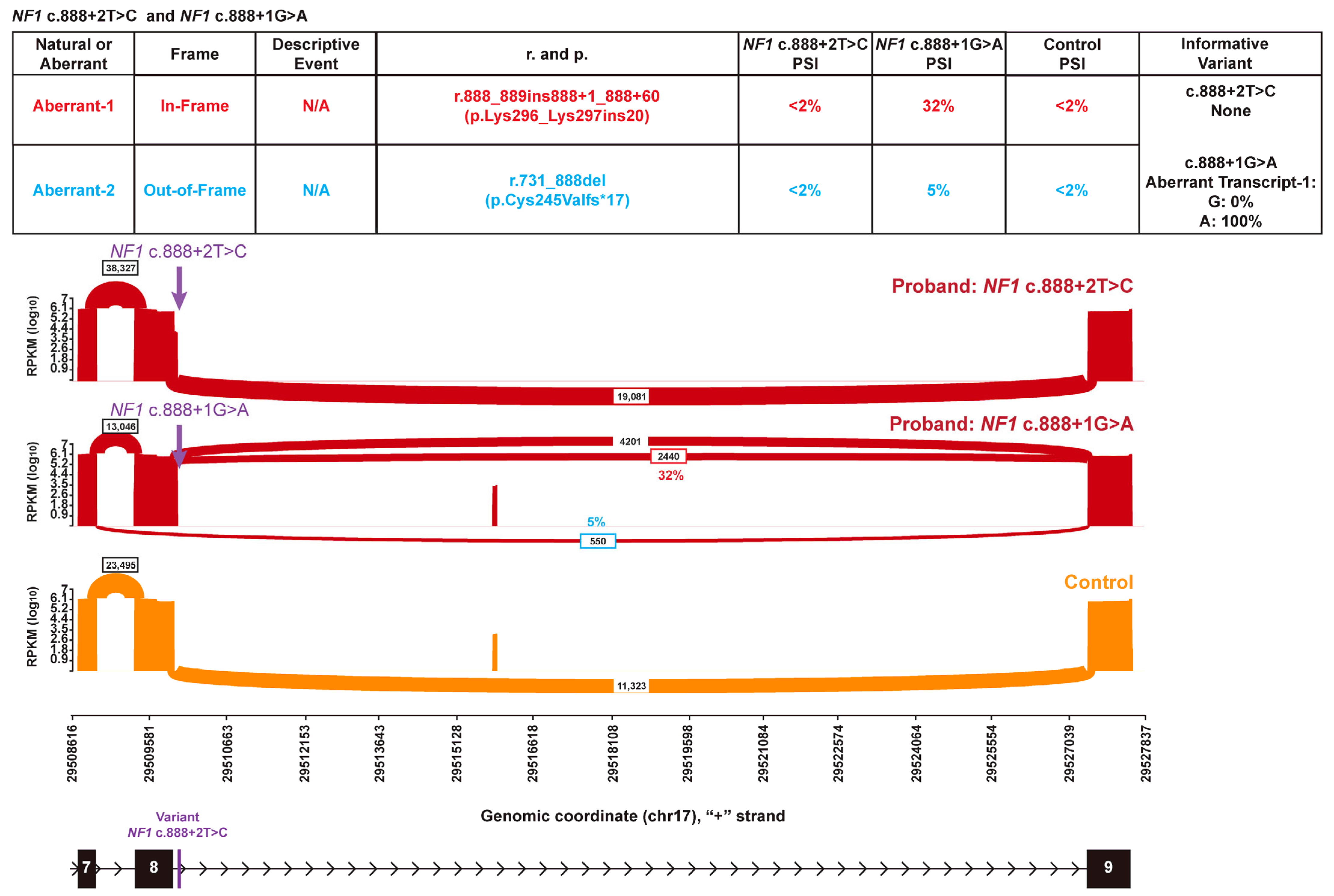

3.3. Spliceosome Impact

3.4. NMD-Escaping

3.5. Cryptic Pyrimidine Tract Modifications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACMG/AMP | American College of Medical Genetics/American College of Medical Genetics |

| CHIP | Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminant Potential |

| FAP | Familial Adenomatous Polyposis |

| NAS | Nonsense-Associated Alternative Splicing |

| NMD | Nonsense-Mediated Decay |

| PSI | Percent Splicing Index |

| PTC | Premature Termination Codon |

| PVS1 | Pathogenic Very_Strong 1 |

| RT-PCR | reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction sequencing |

| VUS | Variant of uncertain significance |

| WT | Wildtype |

References

- Truty, R.; Ouyang, K.; Rojahn, S.; Garcia, S.; Colavin, A.; Hamlington, B.; Freivogel, M.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Nykamp, K.; Aradhya, S. Spectrum of Splicing Variants in Disease Genes and the Ability of RNA Analysis to Reduce Uncertainty in Clinical Interpretation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, C.; Cass, A.; Conner, B.R.; Hoang, L.; Zimmermann, H.; Abualkheir, N.; Burks, D.; Qian, D.; Molparia, B.; Vuong, H.; et al. Mutational and Splicing Landscape in a Cohort of 43,000 Patients Tested for Hereditary Cancer. npj Genom. Med. 2022, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.C.; Hoya, M.d.l.; Wiggins, G.A.R.; Lindy, A.; Vincent, L.M.; Parsons, M.T.; Canson, D.M.; Bis-Brewer, D.; Cass, A.; Tchourbanov, A.; et al. Using the ACMG/AMP Framework to Capture Evidence Related to Predicted and Observed Impact on Splicing: Recommendations from the ClinGen SVI Splicing Subgroup. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 110, 1046–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Burge, C.B. Splicing Regulation: From a Parts List of Regulatory Elements to an Integrated Splicing Code. RNA 2008, 14, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangermano, R.; Garanto, A.; Khan, M.; Runhart, E.H.; Bauwens, M.; Bax, N.M.; Born, L.I.v.d.; Khan, M.I.; Cornelis, S.S.; Verheij, J.B.G.M.; et al. Deep-Intronic ABCA4 Variants Explain Missing Heritability in Stargardt Disease and Allow Correction of Splice Defects by Antisense Oligonucleotides. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 1751–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykke-Andersen, S.; Jensen, T.H. Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay: An Intricate Machinery That Shapes Transcriptomes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuno, C.; Lee, K.; Olivier, M.; Pesaran, T.; Mai, P.L.; Andrade, K.C.d.; Attardi, L.D.; Crowley, S.; Evans, D.G.; Feng, B.-J.; et al. Specifications of the ACMG/AMP Variant Interpretation Guidelines for Germline TP53 Variants. Hum. Mutat. 2021, 42, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mester, J.L.; Ghosh, R.; Pesaran, T.; Huether, R.; Karam, R.; Hruska, K.S.; Costa, H.A.; Lachlan, K.; Ngeow, J.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.; et al. Gene-Specific Criteria for PTEN Variant Curation: Recommendations from the ClinGen PTEN Expert Panel. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Krempely, K.; Roberts, M.E.; Anderson, M.J.; Carneiro, F.; Chao, E.; Dixon, K.; Figueiredo, J.; Ghosh, R.; Huntsman, D.; et al. Specifications of the ACMG/AMP Variant Curation Guidelines for the Analysis of Germline CDH1 Sequence Variants. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 1553–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, K.; Panagiotopoulou, S.K.; McRae, J.F.; Darbandi, S.F.; Knowles, D.; Li, Y.I.; Kosmicki, J.A.; Arbelaez, J.; Cui, W.; Schwartz, G.B.; et al. Predicting Splicing from Primary Sequence with Deep Learning. Cell 2019, 176, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, R.; Conner, B.; LaDuca, H.; McGoldrick, K.; Krempely, K.; Richardson, M.E.; Zimmermann, H.; Gutierrez, S.; Reineke, P.; Hoang, L.; et al. Assessment of Diagnostic Outcomes of RNA Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1913900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber-Katz, S.; Hsuan, V.; Wu, S.; Landrith, T.; Vuong, H.; Xu, D.; Li, B.; Hoo, J.; Lam, S.; Nashed, S.; et al. Quantitative Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Germline Splicing Variants Using a Novel RNA-Massively Parallel Sequencing Assay. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-H.; Wu, H.; Zou, W.-B.; Masson, E.; Fichou, Y.; Gac, G.L.; Cooper, D.N.; Férec, C.; Liao, Z.; Chen, J.-M. Splicing Outcomes of 5′ Splice Site GT>GC Variants That Generate Wild-Type Transcripts Differ Significantly Between Full-Length and Minigene Splicing Assays. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 701652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-H.; Tang, X.-Y.; Boulling, A.; Zou, W.-B.; Masson, E.; Fichou, Y.; Raud, L.; Tertre, M.L.; Deng, S.-J.; Berlivet, I.; et al. First Estimate of the Scale of Canonical 5′ Splice Site GT>GC Variants Capable of Generating Wild-Type Transcripts. Hum. Mutat. 2019, 40, 1856–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayoun, A.N.A.; Pesaran, T.; DiStefano, M.T.; Oza, A.; Rehm, H.L.; Biesecker, L.G.; Harrison, S.M. Recommendations for Interpreting the Loss of Function PVS1 ACMG/AMP Variant Criterion. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 1517–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutmann, D.H.; Ferner, R.E.; Listernick, R.H.; Korf, B.R.; Wolters, P.L.; Johnson, K.J. Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahsold, R.; Hoffmeyer, S.; Mischung, C.; Gille, C.; Ehlers, C.; Kücükceylan, N.; Abdel-Nour, M.; Gewies, A.; Peters, H.; Kaufmann, D.; et al. Minor Lesion Mutational Spectrum of the Entire NF1 Gene Does Not Explain Its High Mutability but Points to a Functional Domain Upstream of the GAP-Related Domain. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 66, 790–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ars, E.; Kruyer, H.; Morell, M.; Pros, E.; Serra, E.; Ravella, A.; Estivill, X.; Lázaro, C. Recurrent Mutations in the NF1 Gene Are Common among Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Patients. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 40, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pros, E.; Gómez, C.; Martín, T.; Fábregas, P.; Serra, E.; Lázaro, C. Nature and mRNA Effect of 282 Different NF1 Point Mutations: Focus on Splicing Alterations. Hum. Mutat. 2008, 29, E173–E193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayling, I.M.; Mautner, V.-F.; Minkelen, R.v.; Kallionpaa, R.A.; Aktaş, S.; Baralle, D.; Ben-Shachar, S.; Callaway, A.; Cox, H.; Eccles, D.M.; et al. Breast Cancer Risk in Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Is a Function of the Type of NF1 Gene Mutation: A New Genotype-Phenotype Correlation. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 56, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, N.; Roca, X.; Hastings, M.L.; Roeder, T.; Krainer, A.R.; Sachidanandam, R. Comprehensive Splice-Site Analysis Using Comparative Genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 3955–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, N.M. Intron Splicing: U12 Spliceosomal Introns Not so ‘Minor’ after All. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R912–R914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luijt, R.B.v.d.; Vasen, H.F.; Tops, C.M.; Breukel, C.; Fodde, R.; Khan, P.M. APC Mutation in the Alternatively Spliced Region of Exon 9 Associated with Late Onset Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. Hum. Genet. 1995, 96, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curia, M.C.; Esposito, D.L.; Aceto, G.; Palmirotta, R.; Crognale, S.; Valanzano, R.; Ficari, F.; Tonelli, F.; Battista, P.; Mariani-Costantini, R.; et al. Transcript Dosage Effect in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis: Model Offered by Two Kindreds with Exon 9 APC Gene Mutations. Hum. Mutat. 1998, 11, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-M.; Lin, J.-H.; Masson, E.; Liao, Z.; Férec, C.; Cooper, D.N.; Hayden, M. The Experimentally Obtained Functional Impact Assessments of 5′ Splice Site GT’GC Variants Differ Markedly from Those Predicted. Curr. Genom. 2020, 21, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Buratti, E. Alternative Splicing: Role of Pseudoexons in Human Disease and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yang, Z.; Kibukawa, M.; Paddock, M.; Passey, D.A.; Wong, G.K.-S. Minimal Introns Are Not “Junk”. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakharkar, M.K.; Chow, V.T.K.; Kangueane, P. Distributions of Exons and Introns in the Human Genome. Silico Biol. 2004, 4, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, S.R.; Kaetzel, C.S.; Peterson, M.L. Cryptic Intron Activation within the Large Exon of the Mouse Polymeric Immunoglobulin Receptor Gene: Cryptic Splice Sites Correspond to Protein Domain Boundaries. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 3446–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janice, J.; Jąkalski, M.; Makałowski, W. Surprisingly High Number of Twintrons in Vertebrates. Biol. Direct 2013, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Copertino, D.W.; Hallick, R.B. Group II Twintron: An Intron within an Intron in a Chloroplast Cytochrome B-559 Gene. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scamborova, P.; Wong, A.; Steitz, J.A. An Intronic Enhancer Regulates Splicing of the Twintron of Drosophila Melanogaster Prospero Pre-mRNA by Two Different Spliceosomes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 1855–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoya, M.d.l.; Soukarieh, O.; López-Perolio, I.; Vega, A.; Walker, L.C.; Ierland, Y.v.; Baralle, D.; Santamariña, M.; Lattimore, V.; Wijnen, J.; et al. Combined Genetic and Splicing Analysis of BRCA1 c.[594-2A>C; 641A>G] Highlights the Relevance of Naturally Occurring In-Frame Transcripts for Developing Disease Gene Variant Classification Algorithms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 2256–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendive, F.M.; Rivolta, C.M.; González-Sarmiento, R.; Medeiros-Neto, G.; Targovnik, H.M. Nonsense-Associated Alternative Splicing of the Human Thyroglobulin Gene. Mol. Diagn. 2005, 9, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bühler, M.; Mühlemann, O. Alternative Splicing Induced by Nonsense Mutations in the Immunoglobulin Mu VDJ Exon Is Independent of Truncation of the Open Reading Frame. RNA 2005, 11, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, B.; Vogl, C. Purifying Selection against Spurious Splicing Signals Contributes to the Base Composition Evolution of the Polypyrimidine Tract. J. Evol. Biol. 2023, 36, 1295–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibley, C.R.; Blazquez, L.; Ule, J. Lessons from Non-Canonical Splicing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolidge, C.J.; Seely, R.J.; Patton, J.G. Functional Analysis of the Polypyrimidine Tract in Pre-mRNA Splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. Suppl. 1997, 25, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zimmermann, H.; Brannan, T.; Young, C.; Ramirez Castano, J.; Horton, C.; Richardson, A.; Molparia, B.; Richardson, M.E. A Plot Twist: When RNA Yields Unexpected Findings in Paired DNA-RNA Germline Genetic Testing. Genes 2025, 16, 1382. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111382

Zimmermann H, Brannan T, Young C, Ramirez Castano J, Horton C, Richardson A, Molparia B, Richardson ME. A Plot Twist: When RNA Yields Unexpected Findings in Paired DNA-RNA Germline Genetic Testing. Genes. 2025; 16(11):1382. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111382

Chicago/Turabian StyleZimmermann, Heather, Terra Brannan, Colin Young, Jesus Ramirez Castano, Carolyn Horton, Alexandra Richardson, Bhuvan Molparia, and Marcy E. Richardson. 2025. "A Plot Twist: When RNA Yields Unexpected Findings in Paired DNA-RNA Germline Genetic Testing" Genes 16, no. 11: 1382. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111382

APA StyleZimmermann, H., Brannan, T., Young, C., Ramirez Castano, J., Horton, C., Richardson, A., Molparia, B., & Richardson, M. E. (2025). A Plot Twist: When RNA Yields Unexpected Findings in Paired DNA-RNA Germline Genetic Testing. Genes, 16(11), 1382. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111382