Gene Mapping and Molecular Marker Development for Controlling Purple-Leaf Trait in Pakchoi (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis (L.) Hanelt)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Material

2.2. Character Statistics

2.3. DNA Extraction

2.4. BSA-Seq Analysis

2.5. Mapping the Gene of Controlling Purple-Leaf Trait

3. Results and Analysis

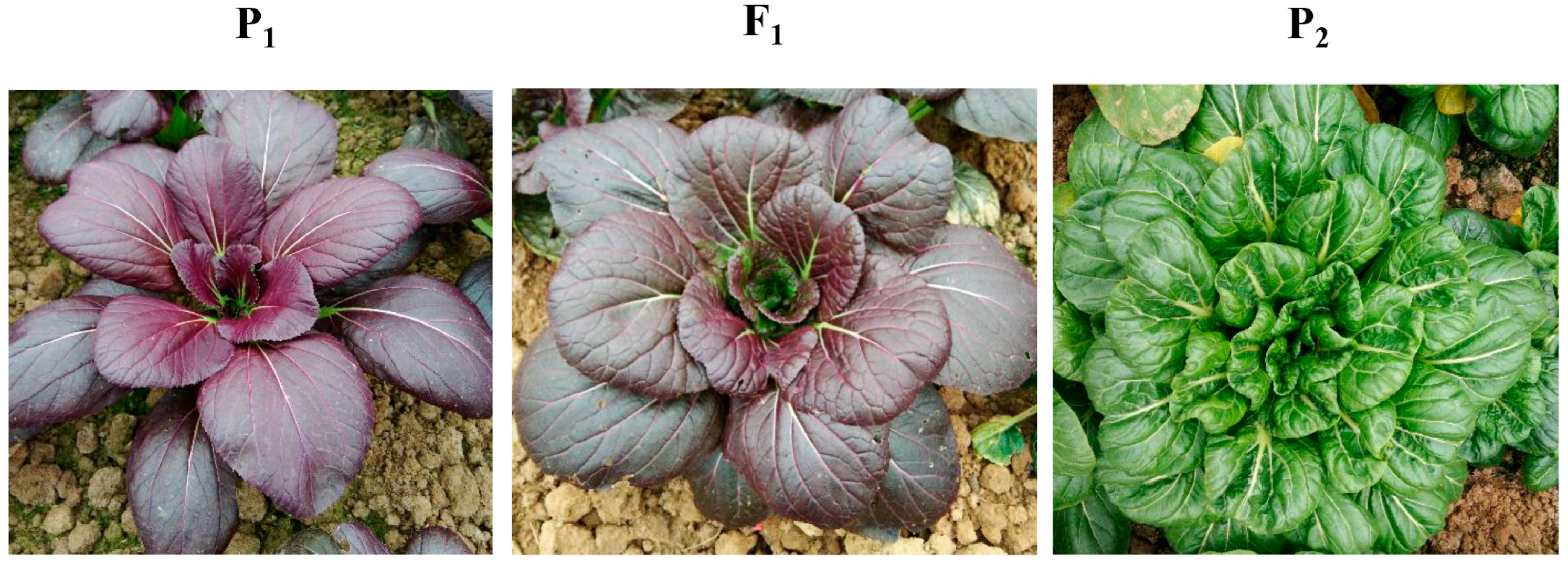

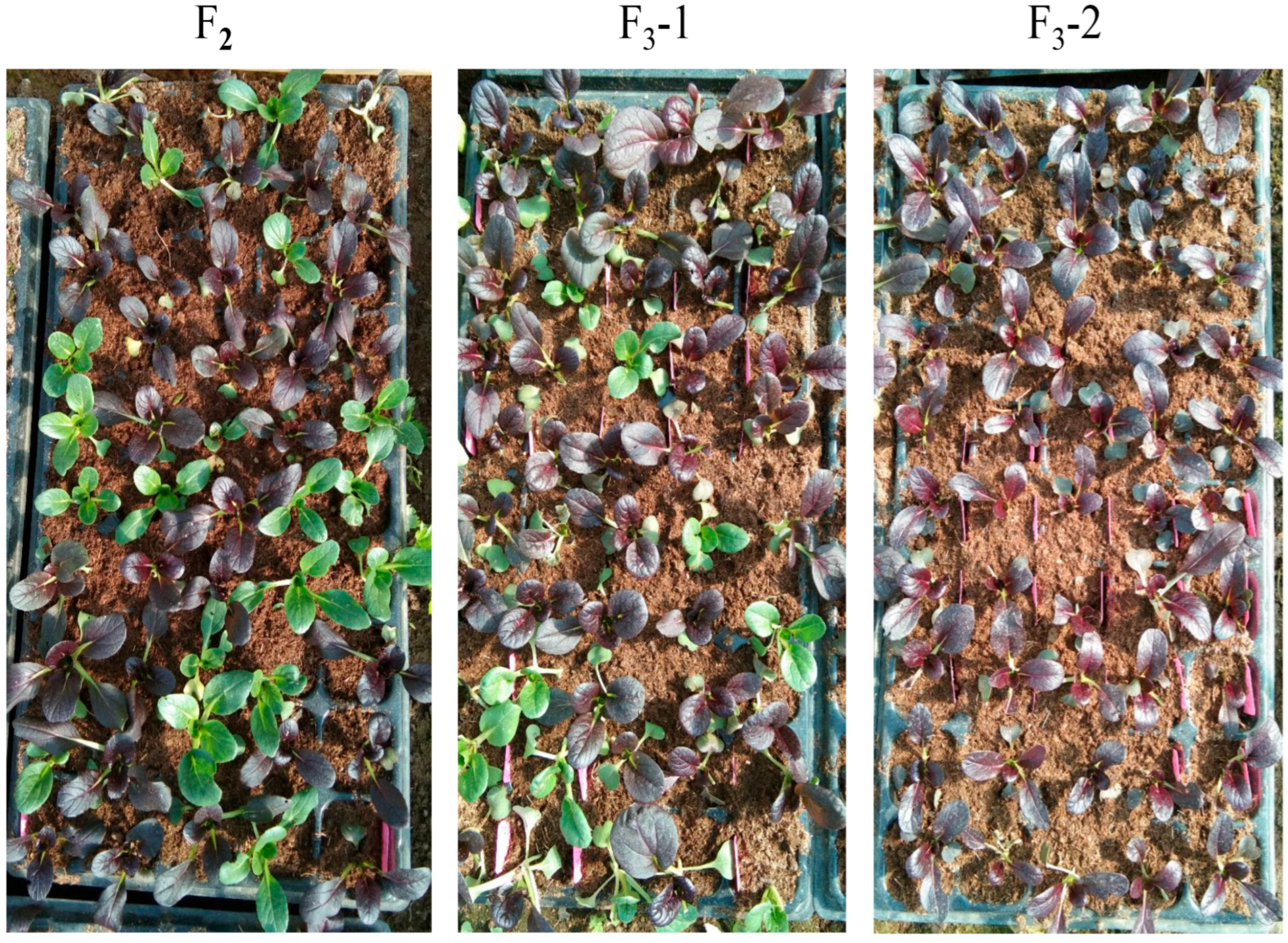

3.1. Genetic Inheritance of the Purple-Leaf Trait

3.2. BSA-Seq Analysis Identifies Candidate Region for Purple-Leaf Gene

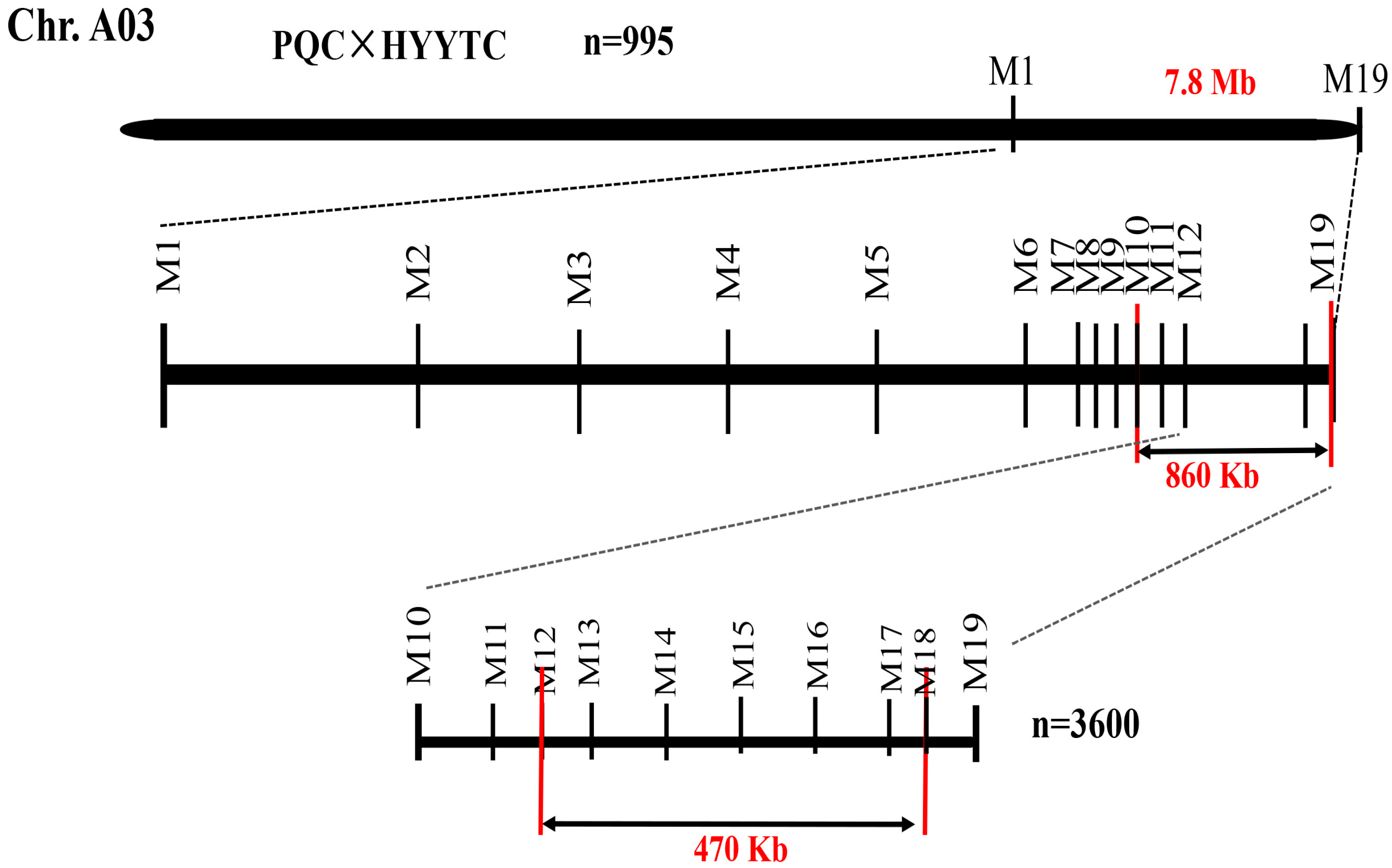

3.3. Fine Mapping of the Purple-Leaf Gene

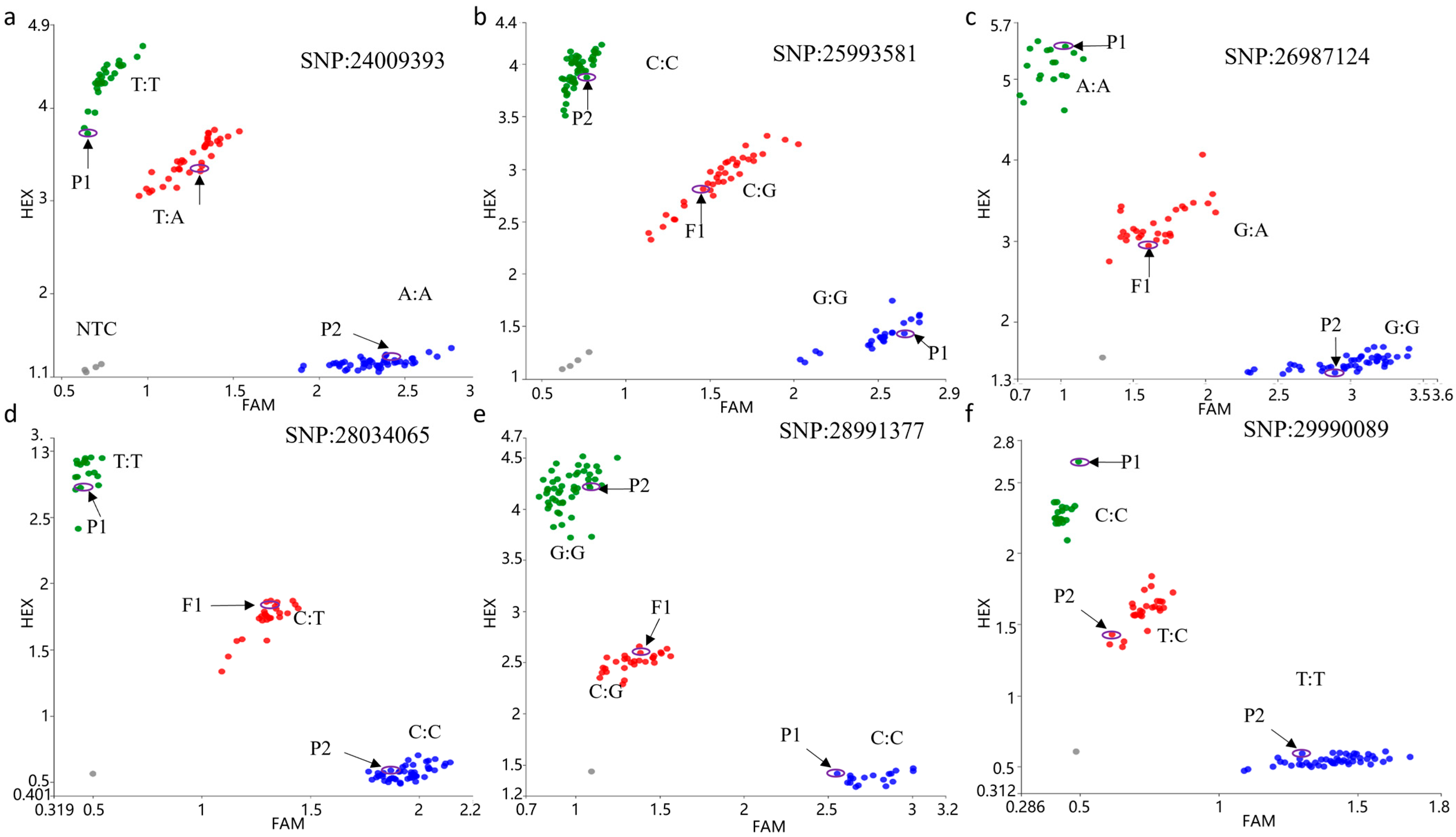

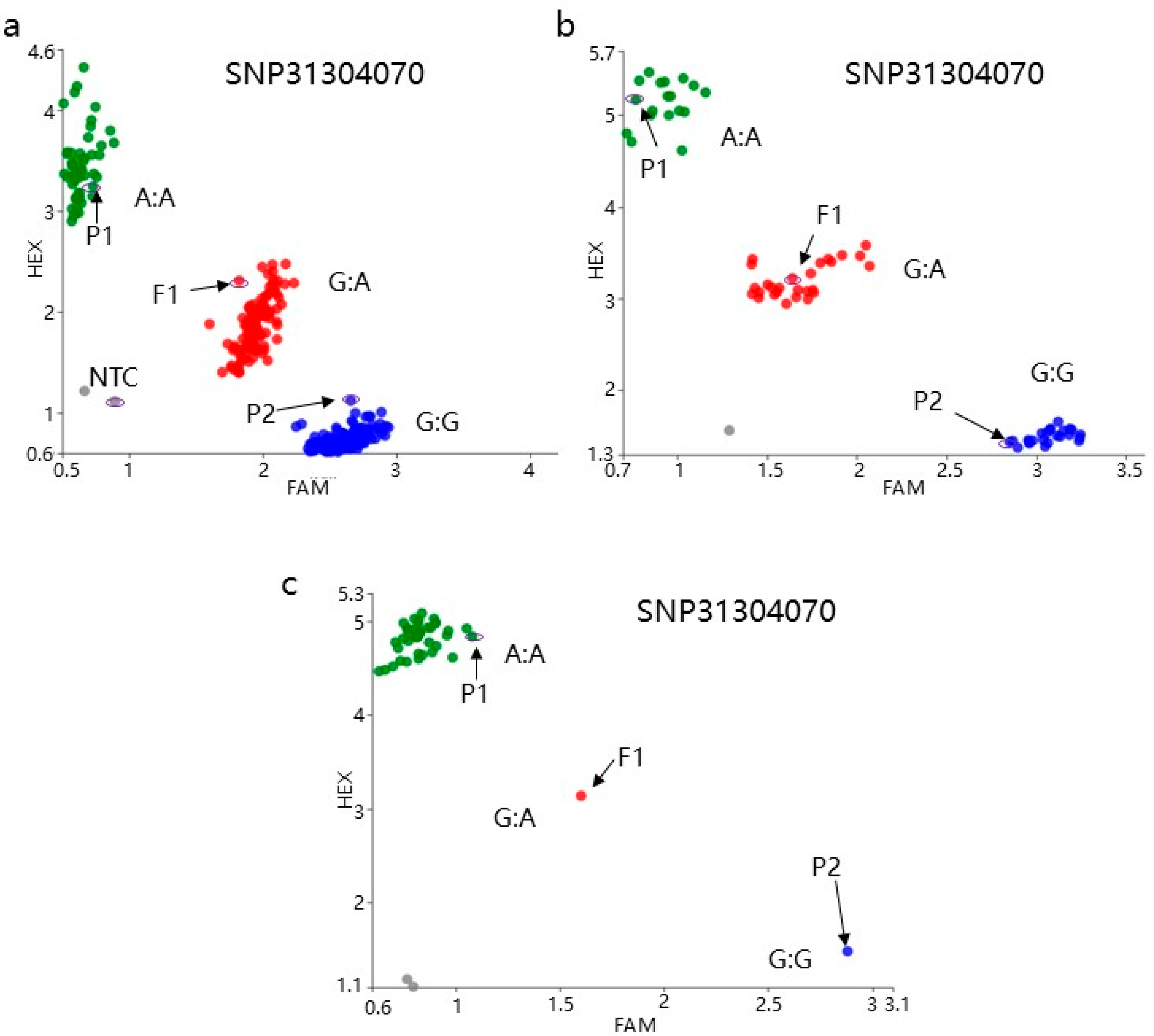

3.4. Molecular Marker Development

4. Discussion

4.1. The Genetic Characteristics of the Gene Controlling Purple-Leaf Trait

4.2. Mapping Interval and Candidate Gene Analysis

4.3. Application of Molecular Marker for Purple-Leaf Trait

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Isaak, C.K.; Petkau, J.C.; Blewett, H.; Karmin, O.; Siow, Y.L. Lingonberry Anthocyanins Protect Cardiac Cells from Oxidative-stress-induced Apoptosis. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2017, 95, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaljit, M.; Priya, R.; Mahetab, H.; Gregory, A. Bioactivity and Anthocyanin Content of Microwave-assisted Subcritical Water Extracts of Manipur Black Rice (Chakhao) Bran and Straw. Future Foods 2021, 3, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Xu, H.; Chen, L.Z.; Fan, X.X.; Jing, Z.G.; Chen, S.; Xu, Z.G. Study of the Relationship between Leaf Color Formation and Anthocyanin Metabolism among Different Purple Pak-choi Lines. Molecules 2020, 25, 4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, B.; Wu, T.; Yang, Y.F.; Fan, L.X.; Wen, M.X.; Su, J.X. Transcriptomic Profiling of Two Pak Choi Varieties with Contrasting Anthocyanin Contents Provides an Insight into Structural and Regulatory Genes in Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Pathway. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.Y.; Huang, T.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.Q.; Chen, L.Z.; Jing, Z.G.; Li, Y.J.; Yang, Q.C.; Xu, H.; et al. Integrated Phenotypic Physiology and Transcriptome Analysis Revealed the Molecular Genetic Basis of Anthocyanin Accumulation in Purple Pak-Choi. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdzinski, C.; Wendell, D.L. Mapping the Anthocyaninless (anl) Locus in Rapid-Cycling Brassica rapa (RBr) to Linkage Group R9. BMC Genet. 2007, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.J. Mapping of a Novel Anthocyanin Locus (Anm) and Screening of Candidate Genes in Brassica rapa. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.Q.; Zhao, J.; Qin, M.L.; Ren, Y.J.; Zhang, H.M.; Dai, Z.H.; Hao, L.Y.; Zhang, L.G. Genetic Analysis and Primary Mapping of the Purple Gene in Purple Heading Chinese cabbage. Hortic. Plant J. 2016, 2, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, Z.F.; Zhang, L.G. Anthocyanin Accumulation, Antioxidant Ability and Stability, and a Transcriptional Analysis of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Purple Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, W.J.; Zhang, D.S.; Yu, S.C.; Zhang, F.L.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Yu, Y.J.; Xu, J.B.; Lu, G.X. Primary Mapping of pur, a Gene Controlling Purple Leaf Color in Brassica rapa. Acta Agric. Boreali-Sin. 2023, 28, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, D.; Yu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, F.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Lu, G.; Su, T. Mapping the BrPur Gene for Purple Leaf Color on Linkage Group A03 of Brassica rapa. Euphytica 2014, 199, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N. Natural Variation and Genetics Mechanism of Anthocyanin and Flavonol Glycosides Metabolism in Brassica rapa. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Gowda, M.; Nair, S.K.; Hao, Z.; Lu, Y.; et al. Applications of Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) in Maize Genetics and Breeding. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 16308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsykun, T.; Rellstab, C.; Dutech, C. Comparative Assessment of SSR and SNP Markers for Inferring the Population Genetic Structure of The Common Fungus Armillaria cepistipes. Heredity 2017, 119, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaki, A.A.; Ahmad, B.; Magaji, U.F.; Abdulrazak, U.K.; Yusuf, B.A.; Hamza, A.B. Optimised Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) DNA Extraction Method of Plant Leaf with High Polysaccharide and Polyphenolic Compounds for Downstream Reliable Molecular Analyses. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 16, 1354–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Abe, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kosugi, S.; Natsume, S.; Mitsuoka, C.; Uemura, A.; Utsushi, H.; Tamiru, M.; Takuno, S.; et al. QTL-seq: Rapid Mapping of Quantitative Trait Loci in Rice by Whole Genome Resequencing of DNA from Two Bulked Populations. Plant J. 2013, 74, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Keurentjes, J.; Bentsink, L.; Koornneef, M.; Smeekens, S. Sucrose-specific Induction of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis Requires the MYB75/PAP1 Gene. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 1840–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravot, A.; Grillet, L.; Wagner, G.; Jubault, M.; Lariagon, C.; Baron, C.; Deleu, C.; Delourme, R.; Bouchereau, A.; Manzanares-Dauleux, M.J. Genetic and Physiological Analysis of the Relationship between Partial Resistance to Clubroot and Tolerance to Trehalose in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2011, 191, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.S.; Zhang, F.L.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Yu, Y.J.; Xu, J.B.; Yu, S.C.; Wang, W.J. Genetic Analysis of Leaf Color Characteristics with Purple Genes on Chinese Cabbage. China Veg. 2011, 2, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Hou, X.L.; Han, K.; Zhang, Z.S.; Hu, C.M. Cloning and Expression Analysis of Anthocyanins Negative Regulatory Factor BrcLBD39 and its Response to Exogenous 6-BA in Non-heading Chinese Cabbage. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2018, 41, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.F.; Guo, Y.P. Review on Crosstalk Regulation Involving in Trehalose-6-phosphate Signal in Plant. Plant Physiol. J. 2016, 52, 394–400. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, Y. TPS1 Transgene Promotes Anthocyanin Accumulation under Drought Stress and Enhances Drought Tolerance in Maize Plants. Plant Physiol. J. 2015, 51, 2054–2062. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.L.; Ni, J.; Chen, M.; Xu, Z. Over-expression of JcTPS1 from Jatropha curcas Induces Early Flowering of Arabidopsis and Improves Anthocyanin Accumulation in Leaves. Mol. Plant Breed. 2018, 16, 255–261. [Google Scholar]

| Population | Total Plants | Purple-Leaf Plants | Green-Leaf Plants | Expected Ratio | χ2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F2 | 5472 | 3998 | 1474 | 3:1 | 1.81 | 0.577 |

| BC1P2 | 705 | 373 | 332 | 1:1 | 1.61 | 0.232 |

| BC1P1 | 86 | 86 | 0 | 1:0 | - | - |

| Sample | Total Reads (bp) | Mapping Rate (%) | Average Depth (X) | Properly Mapped (%) | Cov_Ratio_10X (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-bulk | 159897960 | 95.48 | 32 | 77.74 | 85.69 |

| G-bulk | 153422874 | 95.51 | 31 | 77.68 | 86.04 |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | M11 | M12 | M13 | M14 | M15 | M16 | M17 | M18 | M19 | Color | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mark position | 24009393 | 25993581 | 26987124 | 28034065 | 28990089 | 29990089 | 30100772 | 30402945 | 30600586 | 30820924 | 31150266 | 31180314 | 31209409 | 31304070 | 31409624 | 31521617 | 31632032 | 31655211 | 31686432 | - |

| Recombinants | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | - |

| P1 | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | purple |

| P2 | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | green |

| F1 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | purple |

| A01-A06 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | green |

| A05-A06 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | green |

| A05-F10 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | green |

| A06-D01 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | green |

| A06-D06 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | green |

| A11-C11 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | green |

| A11-D05 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | green |

| A11-H06 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | green |

| A12-F09 | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | purple |

| A32-B04 | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | purple |

| A34-D12 | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | purple |

| A52-H02 | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | H | H | H | H | H | B | B | purple |

| A37-A03 | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | purple |

| Gene ID | Start | End | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bra017876 | 31180442 | 31180972 | Ribosomal protein L23 family protein |

| Bra017877 | 31181511 | 31183086 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017878 | 31184432 | 31185220 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017879 | 31190884 | 31191666 | AP2 domain-containing transcription factor |

| Bra017880 | 31213843 | 31214996 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017881 | 31227608 | 31229937 | Pentatricopeptide (PPR) repeat-containing protein |

| Bra017882 | 31239747 | 31246015 | UDP-glucosyl transferase 75B2 |

| Bra017883 | 31255797 | 31257231 | Agenet domain-containing protein |

| Bra017884 | 31260954 | 31266012 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017885 | 31322931 | 31323275 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017886 | 31341268 | 31341483 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017887 | 31344356 | 31346341 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017888 | 31348727 | 31351464 | Trehalose phosphate synthase 10 |

| Bra017889 | 31354005 | 31356742 | Formin homology 2 domain-containing protein |

| Bra017890 | 31356980 | 31361049 | E1 alpha subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex |

| Bra017891 | 31362626 | 31367740 | SIN3-like 5 |

| Bra017892 | 31372380 | 31372692 | 5-Aminolevulinic acid dehydrtase 1 |

| Bra017893 | 31383010 | 31384373 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017894 | 31386945 | 31387686 | Leucine-rich repeat protein kinase |

| Bra017895 | 31391442 | 31392231 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017896 | 31417632 | 31423472 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017897 | 31437219 | 31450288 | Aminophosphlipid ATPase 3 |

| Bra017898 | 31472604 | 31473209 | Thioredoxin H-type 7 |

| Bra017899 | 31495945 | 31497816 | Pentatricopeptide Repeat Protein |

| Bra017900 | 31522225 | 31530698 | UDP-xylosyltransferase |

| Bra017901 | 31540532 | 31547659 | Dynamin-like 3 |

| Bra017902 | 31570538 | 31571898 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017903 | 31590827 | 31591348 | Unknown protein |

| Bra017904 | 31594274 | 31595090 | Unknown protein |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, B.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Ouyang, L.; He, L.; Chen, L.; Jing, Z.; Huang, T.; et al. Gene Mapping and Molecular Marker Development for Controlling Purple-Leaf Trait in Pakchoi (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis (L.) Hanelt). Genes 2025, 16, 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101184

Song B, Yang Q, Zhang W, Yang X, Zhang L, Ouyang L, He L, Chen L, Jing Z, Huang T, et al. Gene Mapping and Molecular Marker Development for Controlling Purple-Leaf Trait in Pakchoi (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis (L.) Hanelt). Genes. 2025; 16(10):1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101184

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Bo, Qinyu Yang, Wenqi Zhang, Xiao Yang, Li Zhang, Lin Ouyang, Limei He, Longzheng Chen, Zange Jing, Tao Huang, and et al. 2025. "Gene Mapping and Molecular Marker Development for Controlling Purple-Leaf Trait in Pakchoi (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis (L.) Hanelt)" Genes 16, no. 10: 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101184

APA StyleSong, B., Yang, Q., Zhang, W., Yang, X., Zhang, L., Ouyang, L., He, L., Chen, L., Jing, Z., Huang, T., Xu, H., Li, Y., & Yang, Q. (2025). Gene Mapping and Molecular Marker Development for Controlling Purple-Leaf Trait in Pakchoi (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis (L.) Hanelt). Genes, 16(10), 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101184