Cognitive–Behavioral Profile in Pediatric Patients with Syndrome 5p-; Genotype–Phenotype Correlationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Cohort

2.2. The Procedure

2.3. SNP-Arrays

2.4. Neuropsychological Assessment Instruments

- Battelle Development Inventory [39]. The Battelle Developmental Inventory is a battery designed to assess the key developmental skills of children from birth to age 8. It was developed by Newborg, Stock, and Wnek in 1984 and translated and adapted into Spanish in 1996 [39]. Its application is individual and typified. It consists of 341 items grouped into five areas: Personal/Social, Adaptive, Motor, Communication, and Cognitive. The collection of information is carried out through three procedures: (i) Structured examination. In which the examiner applies the items and provides the stimuli in a controlled environment. (ii) Observation. The observation of the subject in different environments, such as family and school, allows obtaining information regarding many of the aspects to be evaluated, especially those related to relationships and social interaction. (iii) Informative interview. The aspects and/or behaviors that can be evaluated more accurately with information provided by the family, teachers, or other people in their immediate environment, are asked and shared in an informative interview. By collecting information from three different sources, the information is contrasted and adjusted to the actual level of the subjects. Although some of the subjects in the sample were over the chronological age of the one collected in this test, none of them had a higher developmental age.

- Inventory of Behavioral Problems (BPI-01) [40]. It was developed by Rojahn in 2001, and translated and adapted into Spanish in 2008 by García-Villamisar. The Conduct Problems Inventory (BPI-01) is a questionnaire consisting of 52 items, which measures the self-injurious behavior (14 items), stereotyped behavior (24 items), and aggressive/destructive behavior (11 items) of the subjects evaluated. In addition, it contains 3 items, one in each scale, where you can add behaviors that are not explicitly listed in that category. Self-injurious behaviors are those that cause harm to one’s subject, stereotyped behaviors are inappropriate acts that occur habitually and repetitively, and aggressive or destructive behaviors are deliberate attacks against other individuals or objects. It is completed by the parents, or a person close to the subject, who must assess the frequency and severity of the behaviors described. The evaluation is made through a Likert scale of 4 points for the frequency of behavior (every month, every week, daily, every hour), and 3 points for severity (mild, moderate, severe). If the behavior does not occur, 0 is scored. Confirmatory factor analyses have provided support for the factorial validity of the measure. In the analysis of the internal consistency of BPI-01, they found a Cronbach’s α of 0.83. The subscales obtained alphas of 0.61 (self-injurious behavior), 0.79 (stereotyped behavior), and 0.82 (aggressive/destructive behavior) [40].

- The Repetitive Behaviors Questionnaire (RBQ) [41]. The RBQ is a questionnaire that assesses the frequency of 19 repetitive behaviors of children and adults with and without language. Respondents rate the frequency of operationally defined behaviors during the previous month. The response format is a Likert scale from 0 to 4 (never, once a month, once a week, once a day, or more than once a day). The results are grouped into 5 subscales: stereotyped behavior, compulsive behavior, limited preferences, repetitive speech, and insistence on monotony. It offers a clinical cut-off point for the different elements of the subscales. Behaviors that occur “once a day” or “more than once a day” were considered clinically important, that is, if a score of three points or more is obtained in a behavior. The stereotyped behavior subscale is composed of 3 items and evaluates the repetitive, and purposeless, movements of the body, a part of it, or objects. Compulsive behavior includes cleaning behaviors, hoarding, and unusual rituals and actions. This subarea is composed of 8 items. Limited preferences evaluate exaggerated attachment to people and objects, and consist of 3 items. The repetitive speech subarea includes 3 items and reflects whether the subject repeats phrases, words, questions, or what he has just heard; and the insistence on monotony values, with the preference for routine and order, consists of 2 items. In the analysis of internal consistency, they found Cronbach’s α of 0.80 for the total test and 0.70 for the subscales of repetitive behavior and stereotyped behavior. The alphas of the other three subscales were lower, limited preferences (α = 0.50), repetitive speech (α = 0.54), and insistence on monotony (α = 0.65) [41].

- Diagnostic Evaluation for the Severely Disabled (DASH-II) [42]. The Diagnostic Evaluation for the Severely Disabled (DASH-II) is composed of 84 items that allow the detection of psychiatric and emotional disorders in adults with ID and great support needs. It was developed by Matson in 1995, and translated and adapted into Spanish in 1999 by Novell, Forgas, and Medinyá. The DASH-II is the test that has the greatest international recognition to evaluate psychiatric problems in people with intellectual disabilities. In addition, we have its translation and adaptation into Spanish. Although the subjects of the sample were children, the lack of tests aimed at this specific population and the need to assess these aspects meant that it was included in the study and that the results were analyzed descriptively.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Limitations

3. Results

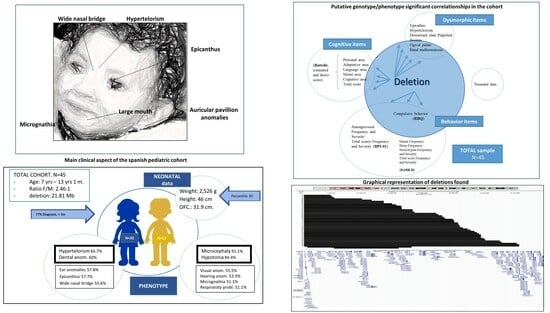

3.1. The Cohort

3.2. Cognitive Aspects

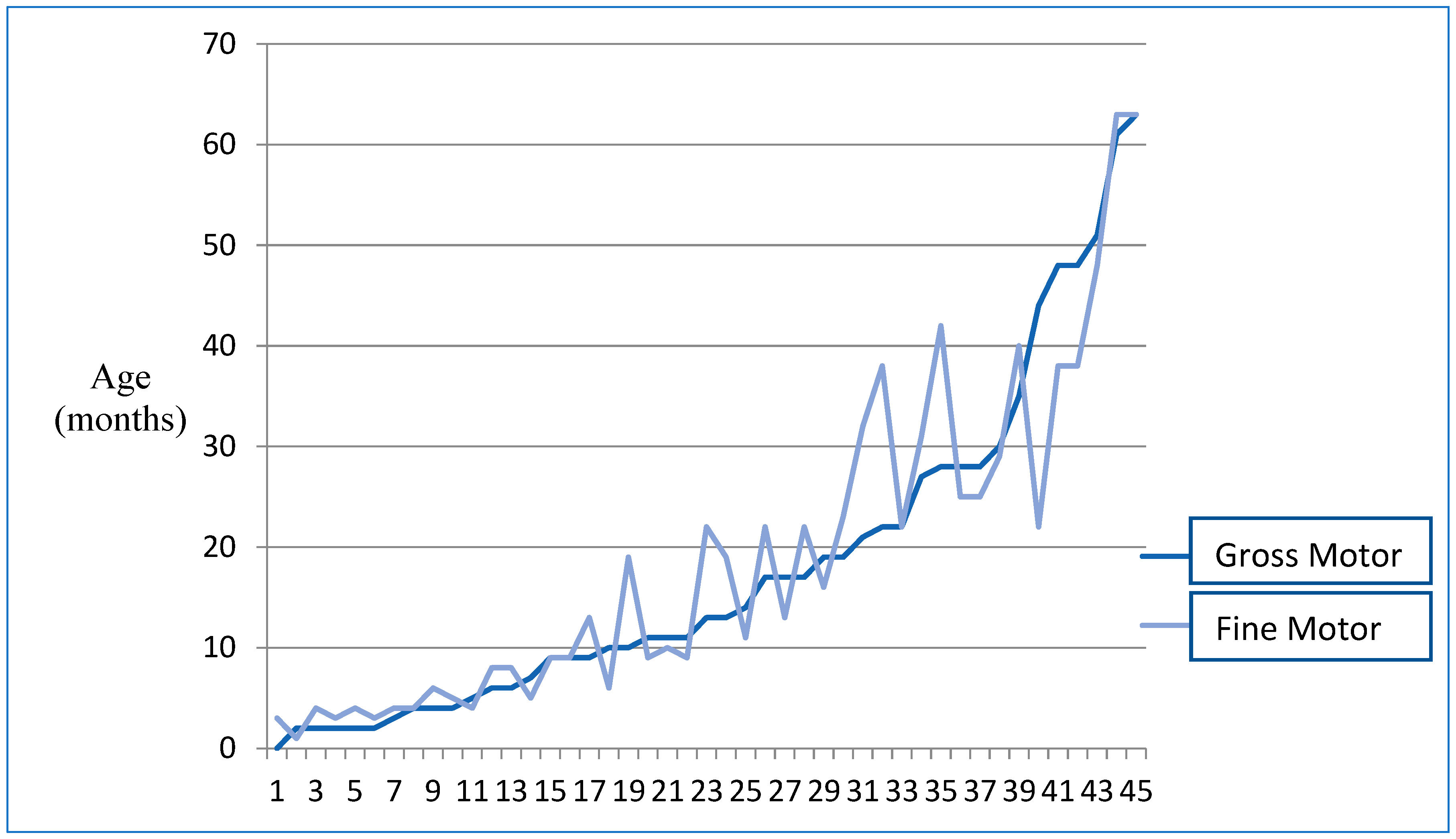

3.2.1. Motor Aspects

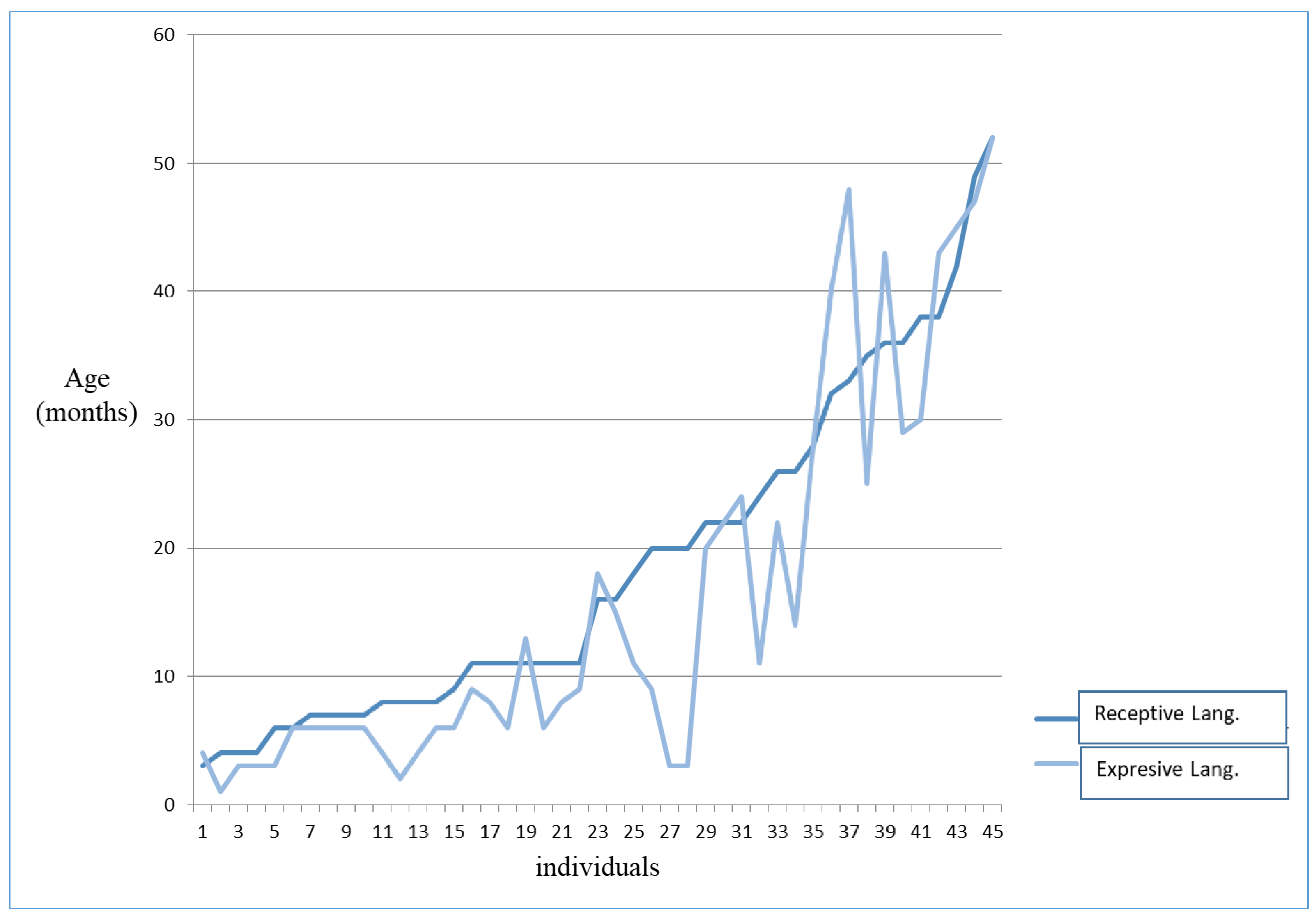

3.2.2. Language–Communicative Aspects

3.3. Behavioral Aspects

3.4. Distribution of Cognitive Aspects according to Gender

3.5. Distribution of Behavioral Aspects according to Gender

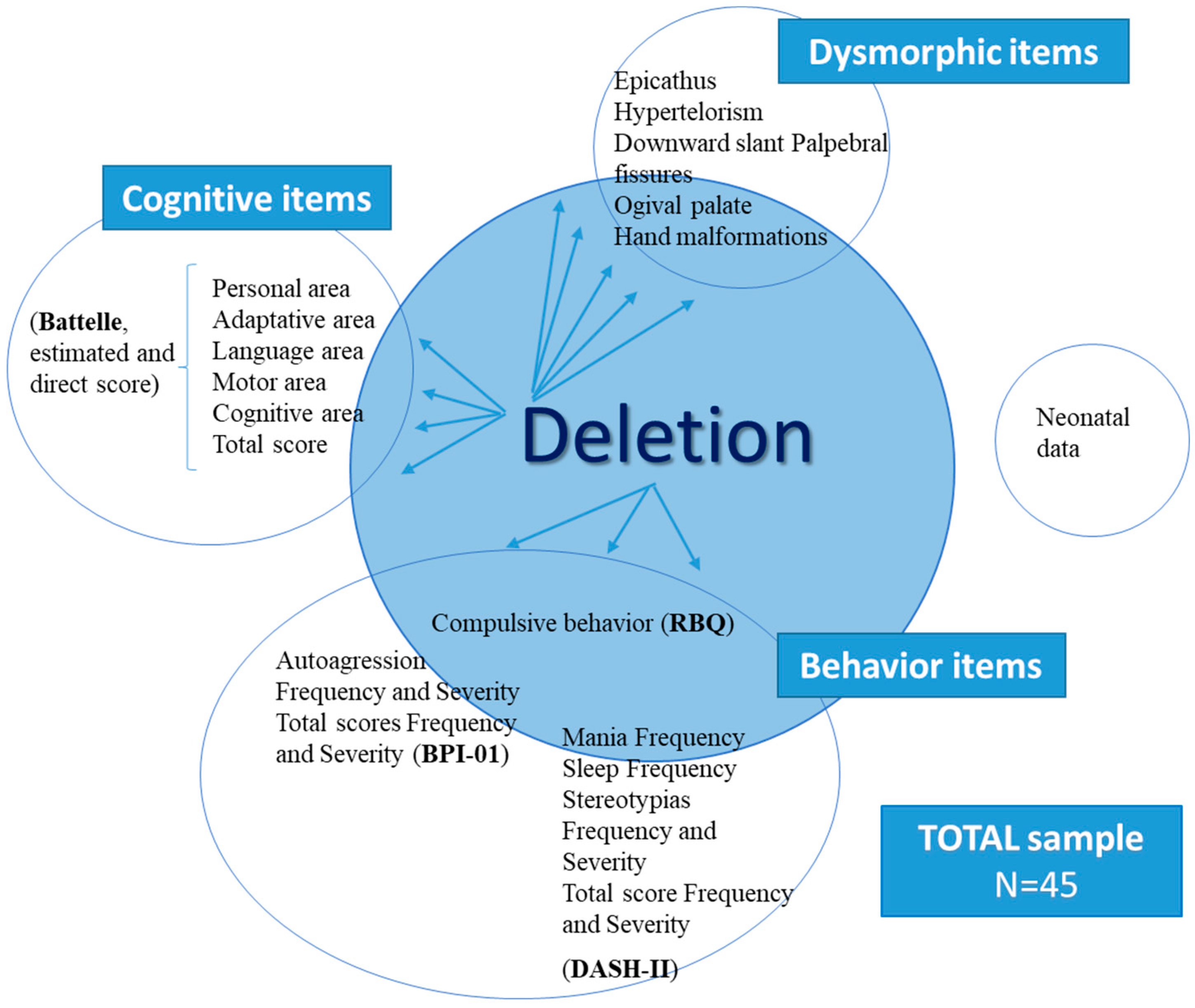

3.6. Correlation between Loss of Genetic Material and Cognitive Aspects

3.7. Correlation between Loss of Genetic Material and Behavioral Aspects

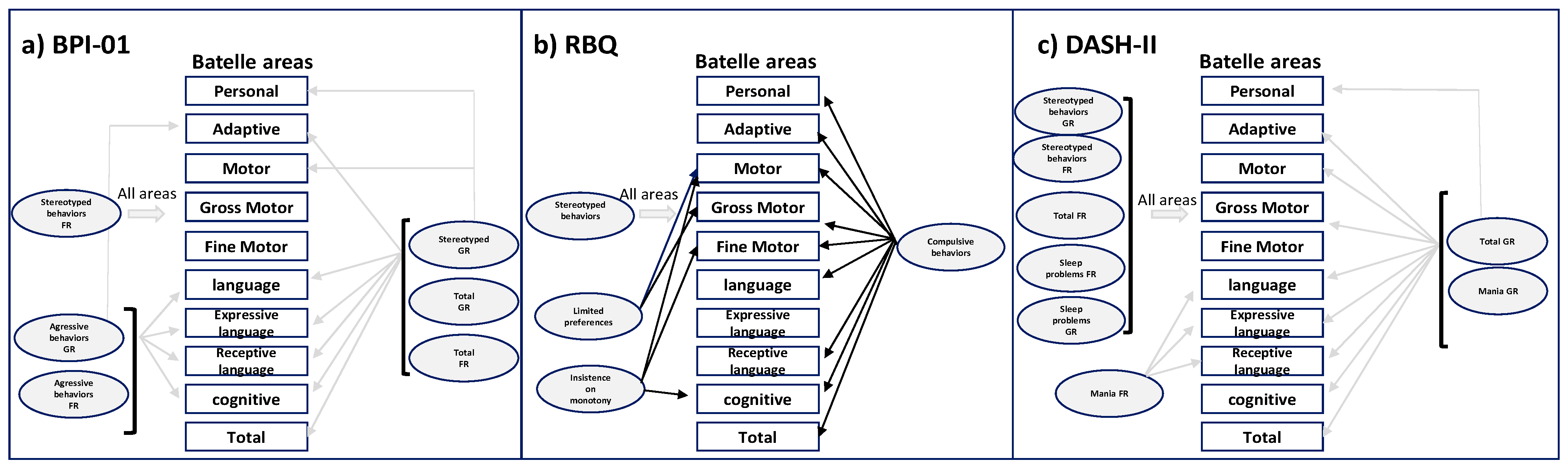

3.8. Correlation between Cognitive Variables and Behavioral Aspects

4. Discussion

4.1. Behavioral Profile of Minors with S5p-

4.2. Cognitive–Behavioral Profile and Genotype of Minors with S5p-

4.3. Sex as a Differentiating Factor

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lejeune, J.; Lafourcade, J.; Berger, R.; Vialatte, J.; Boeswillwald, M.; Seringe, P.; Turpin, R. Trois case de deletion partielle du bras court d’un chromosome 5. C. R. Hebd. Séances L’Acad. Sci. 1963, 257, 3098–3102. [Google Scholar]

- Elmakky, A.; Carli, D.; Lugli, L.; Torelli, P.; Guidi, B.; Falcinelli, C.; Fini, S.; Ferrari, F.; Percesepe, A. A three-generation family with terminal microdeletion involving 5p15.33-32 due to a whole-arm 5;15 chromosomal translocation with a steady phenotype of atypical cri du chat syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2014, 57, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Jiang, J.H.; Li, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.N.; Dong, X.S.; Huang, Y.Y.; Son, X.M.; Lu, X.; Chen, Z. A familial cri-du-chat/5p deletion syndrome resulted from rare maternal complex chromosomal rearrangements (ccrs) and/or possible chromosome 5p chromothripsis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Pang, J.; Hu, J.; Jia, Z.; Xi, H.; Ma, N.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Tang, C.; et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of 12 prenatal cases of Cri-du-chat syndrome. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2020, 8, e1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, A.D.; Goodart, S.A.; Gallardo, T.D.; Overhauser, J.; Lovett, M. Five novel genes from the cri-du-chat critical region isolated by direct selection. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995, 4, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overhauser, J.; Huang, X.; Gersh, M.; Wilson, W.; McMahon, J.; Bengtsson, U.; Rojas, K.; Meyer, M.; Wasmuth, J.J. Molecular and phenotypic mapping of the short arm of chromosome 5: Sublocalization of the critical region for the cri-du-chat syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994, 3, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevado, J.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Mena, R.; Palomares-Bralo, M.; Vallespín, E.; Ángeles Mori, M.; Tenorio, J.A.; Gripp, K.W.; Denenberg, E.; Del Campo, M.; et al. PIAS4 is associated with macro/microcephaly in the novel interstitial 19p13.3 microdeletion/microduplication syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 23, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K.; Bramble, K.; Munir, F.; Pigram, J. Cognitive functioning in children with typical cri du chat (5p-) syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1999, 41, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 3rd ed.; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, L.M.; Whetton, C.; Pintilie, D. The British Picture Vocabulary Scale; NFER-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D. Test for Reception of Grammar, Version 2 (TROG2); Pearson Assessment: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, M.F. Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test; Academic Therapy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Reynell, J. Escala Para Evaluar el Desarrollo del Lenguaje; Mepsa: Barcelona, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, R.; Fristoe, M. Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation; American Guidance Services: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Dykens, E.M.; Clarke, D.J. Correlates of maladaptive behavior in individuals with 5p-(cri du chat) syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 752–756. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.J.; Reilly, A.; Henley, J. Comparison of Assessment Results of Children with Low Incidence Disabilities. Educ. Train. Dev. Disabil. 2008, 43, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreirós-Martínez, R.; López-Manzanares, L.; Alonso-Cerezo, C. Hallazgo inesperado de síndrome cri du chat en una paciente adulta mediante array-CGH. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 59, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondoh, T.; Shimokawa, O.; Harada, N.; Doi, T.; Yun, C.; Gohda, Y.; Kinoshita, F.; Matsumoto, T.; Moriuchi, H. Genotype-phenotype correlation of 5p-syndrome: Pitfall of diagnosis. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 50, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buggenhout, G.J.; Pijkels, E.; Holvoet, M.; Schaap, C.; Hamel, B.C.; Fryns, J.P. Cri du chat syndrome: Changing phenotype in older patients. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 90, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.I.; Marinescu, R.C.; Punnett, H.H.; Tenenholz, B.; Overhauser, J. 5p14 deletion associated with microcephaly and seizures. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 37, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cornish, K. The neuropsychological profile of Cri du Chat Syndrome without significant learning disability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1996, 38, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlin, M.E. The improved prognosis in Cri-du-chat (5P-) syndrome. In Key Issues in Mental Retardation Research, Proceedings of the 8th World Congress of the International Association for the Scientific Study of Mental Deficiency, Dublin, Ireland, 21–25 Agust 1988; Fraser, E.W.I., Ed.; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, M.G.; Burrow, W.; Wolford, P.L. The Aberrant Behavior Checklist Community: Factor validity and effect of subject variables for adults in group homes. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 1995, 100, 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish, K.; Pigram, J. Developmental and behavioural characteristics of cri-du-chat syndrome. Arch. Dis. Child. 1996, 75, 448–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, M.S.; Cornish, K. A survey of the prevalence of stereotypy, self-injury, and aggression in children and young adults with Cri du Chat syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2002, 46, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarimski, K. Early play behaviour in children with 5p-(Cri-du-Chat) syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2003, 47, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.; Howlin, P. Autism spectrum disorders in genetic syndromes: Implications for diagnosis, intervention and understanding the wider ASD population. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2009, 53, 852–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honjo, R.S.; Mello, C.B.; Pimenta, L.S.E.; Nuñes-Vaca, E.C.; Benedetto, L.M.; Khoury, R.; Befi-Lopes, D.M.; Kim, C.A. Cri du Chat syndrome: Characteristics of 73 Brazilian patients. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2018, 62, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, M.C.T.V.; Emerich, D.R.; Orsati, F.T.; Rimério, R.C.; Gatto, K.R.; Chappaz, I.O.; Kim, C.A. A description of adaptive and maladaptive behaviour in children and adolescents with Cri-du-chat syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K.; Oliver, C.; Standen, P.; Bramble, D.; Collins, M. Cri-Du-Chat Syndrome: Handbook for Parents and Professionals, 2nd ed.; Cri du Chat Syndrome Support Group: Earl Shilton, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, L.E.; Brown, J.A.; Wolf, B. Psychomotor development in 65 home-reared children with cri-du-chat síndrome. J. Pediatr. 1980, 97, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, E.A.; Vineland, N.J. Training School y American Guidance Service. In Vineland Social Maturity Scale: Condensed Manual of Directions; American Guidance Service: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Skuse, D.H. Rethinking the nature of genetic vulnerability to autistic spectrum disorders. Trends Genet. 2007, 23, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.; Oliver, C.; Arron, K.; Burbidge, C.; Berg, K. The prevalence and phenomenology of repetitive behavior in genetic syndromes. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claro, A.; Cornish, K.; Gruber, R. Association between fatigue and autistic symptoms in children with Cri du Chat syndrome. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 116, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.; Oliver, C.; Berg, K.; Kaur, G.; Jephcott, L.; Cornish, K. Prevalence of autism spectrum phenomenology in Cornelia de Lange and Cri du Chat syndromes. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2008, 113, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, J.; Howlin, P.; Hastings, R.P.; Beaumont, S.; Griffith, G.M.; Petty, J.; Tunnicliffe, P.; Yates, R.; Villa, D.; Oliver, C. Social behavior and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder in Angelman, Cornelia de Lange and Cri du Chat syndromes. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 118, 262–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, L.; Moss, J.; Nelson, L.; Oliver, C. Contrasting age related changes in autism spectrum disorder phenomenology in Cornelia de Lange, Fragile X, and Cri du Chat syndromes: Results from a 2.5 year follow-up. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2015, 169, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newborg, J.; Stock, J.R.; Wnek, L. Traslation to Spanish: De la Cruz y González. In Inventario de Desarrollo Battelle; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rojahn, J.; Matson, J.L.; Lott, D.; Esbensen, A.J.; Smalls, Y. The Behavior Problems Inventory: An instrument for the assessment of self-injury, stereotyped behavior, and aggression/destruction in individuals with developmental disabilities. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.; Oliver, C. The Repetitive Behaviours Questionnaire (RBQ). In Manual for Administration and Scorer Interpretation; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Matson, J. The Diagnostic Assessment for Several Handicapped II; Scientific Publishers Inc.: Singapore, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish, K.; Munir, F. Receptive and expressive language skills in children with cri du Chat syndrome. J. Commun. Disord. 1998, 31, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverría, A.; Mínguez, P. Síndrome de “Maullido de Gato”, Guía Para Padres y Educadores; Consejería de Sanidad, Gobierno de Catabria: Santander, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cerruti Mainardi, P.; Guala, A.; Pastore, G.; Pozzo, G.; Dagna Bricarelli, F.; Pierluigi, M. Psychomotor development in Cri du Chat Syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2000, 57, 459–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guala, A.; Spunton, M.; Tognon, F.; Pedrinazzi, M.; Medolago, L.; Cerutti Mainardi, P.; Spairani, S.; Malacarne, M.; Finale, E.; Comelli, M.; et al. Psychomotor Development in Cri du Chat Syndrome: Comparison in Two Italian Cohorts with Different Rehabilitation Methods. Sci. World J. 2016, 2016, 3125283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, E.G.; Levin, L.; McConnachie, G.; Carlson, J.; Kemp, D.; Smith, C. Intervención Comunicativa Sobre los Problemas de Comportamiento; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rojahn, J.; Rowe, E.W.; Sharber, A.C.; Hastings, R.; Matson, J.L.; Didden, R.; Kroes, D.B.H.; Dumont, E.L.M. The Behavior Problems Inventory-Short Form for individuals with intellectual disabilities: Part I: Development and provisional clinical reference data. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 56, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojahn, J.; Rowe, E.W.; Sharber, A.C.; Hastings, R.; Matson, J.L.; Didden, R.; Kroes, D.B.H.; Dumont, E.L.M. The Behavior Problems Inventory-Short Form for individuals with intellectual disabilities: Part II: Reliability and validity. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, L.E.; Brown, J.A.; Nance, W.E.; Wolf, B. Clinical heterogeneity in 80 home-reared children with cri-du-chat syndrome. J. Paediatr. 1983, 102, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerruti Mainardi, P.; Perfumo, C.; Cali, A.; Coucourde, G.; Pastore, G.; Cavani, S.; Zara, F.; Overhauser, J.; Pierluigi, M.; Bricarelli, F. Clinical and molecular characterisation of 80 patients with 5p deletion: Genotype-phenotype correlation. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 38, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espirito Santo, L.D.; Moreira, L.M.; Riegel, M. Cri-Du-Chat Syndrome: Clinical Profile and Chromosomal Microarray Analysis in Six Patients. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 5467083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, R.C.; Cerruti, P.; Collins, M.R.; Kouahou, M.; Coucourde, G.; Pastore, G.; Overhauser, J. Growth charts for cri-du-chat syndrome: An international collaborative study. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 94, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Terminal deletion | 43 | 95.50 |

| Interstitial deletion | 2 | 4.40 |

| Familial Translocation | 5 | 11.10 |

| Translocation de novo | 8 | 17.80 |

| Terminal deletion originated from a parental mosaicism | 1 | 2.00 |

| Mosaicism | 0 | - |

| Ring chromosome | 0 | - |

| Additional duplication | 20 | 44.40 |

| Other rearrangements | 3 | 6.70 |

| Areas | Minimum Score | Maximum Score | Mean (Age in Months) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal | 2 | 64 | 22.89 | 16.45 |

| Adaptive A | 1 | 62 | 21.20 | 18.64 |

| Motor | 1 | 61 | 18.02 | 14.89 |

| Gross Motor | 0 | 63 | 18.09 | 16.43 |

| Fine Motor | 1 | 63 | 18.89 | 15.90 |

| Language | 3 | 74 | 17.51 | 15.65 |

| Expressive Language | 1 | 52 | 16.20 | 5.04 |

| Receptive Language | 3 | 74 | 18.27 | 12.59 |

| Cognitive | 2 | 90 | 24.16 | 19.88 |

| Total | 2 | 60 | 20.73 | 15.86 |

| Younger, <3 y (N = 8) | Older, >3 y (N = 37) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 1 y, 7 m | 7 y, 4 m |

| Receptive Language | 6 m | 1 y, 7 m |

| Expressive Language | 4 m | 1 y, 5 m |

| Total language | 5 m | 1 y, 5 m |

| Linguistic Age (Months) | Receptive Lang. | Expressive Lang. | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Chronologic Age | N | Chronologic Age | N | Chronologic Age | |

| 0–12 | 14 | 3–13 | 18 | 3–13.1 | 18 | 3–13 |

| 12–24 | 10 | 3.7–13.1 | 8 | 3.8–12.1 | 8 | 4.5–13.1 |

| 24–36 | 8 | 4.5–10.2 | 4 | 8.1–12.9 | 7 | 4.5–12.9 |

| 36–48 | 3 | 6.3–12.9 | 6 | 4.5–11 | 3 | 6.3–8.8 |

| +48 | 2 | 8.7–8.8 | 1 | 8.7 | 1 | 8.7 |

| N | Range Scores | Mean Score (0–4 FR)+ (0–3 GR) | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-harm behavior | Frequency Severity | 37 37 | 1–12 1–11 | 4.60 3.91 | 3.79 3.23 |

| Stereotyped behavior | Frequency Severity | 33 33 | 1–18 1–11 | 3.78 2.87 | 3.56 2.60 |

| Destructive aggressive behavior | Frequency Severity | 32 32 | 1–9 1–6 | 2.29 2.18 | 2.15 1.85 |

| Total | Frequency Severity | 40 40 | 1–26 1–23 | 10.67 8.96 | 8.05 6.54 |

| N | Range Scores | Mean Score (0–4) | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereotyped behavior | 13 | 1–8 | 2.78 | 2.37 |

| Compulsive behavior | 8 | 1–6 | 0.38 | 1.72 |

| Limited preferences | 21 | 1–4 | 1.31 | 1.58 |

| Repetitive speech | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Insistence on monotony | 18 | 1–4 | 0.98 | 1.30 |

| Total | 39 | 0–15 | 5.44 | 4.05 |

| N | Range Scores | Mean Score | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impulses | Frequency Severity | 24 24 | 0–4 0–3 | 0.91 0.78 | 1.10 0.88 |

| Organic | Frequency Severity | 33 33 | 0–2 0–1 | 0.11 0.02 | 0.44 0.15 |

| Anxiety | Frequency Severity | 0 0 | - - | - - | - - |

| Mood | Frequency Severity | 16 16 | 0–4 0–2 | 0.78 0.47 | 1.13 0.69 |

| Mania | Frequency Severity | 20 20 | 0–4 0–2 | 1.02 1.02 | 1.20 1.20 |

| Autism | Frequency Severity | 36 36 | 0–7 0–7 | 3.22 2.58 | 2.25 1.95 |

| Schizophrenia | Frequency Severity | 0 0 | - - | - - | - - |

| Stereotypies | Frequency Severity | 31 31 | 0–6 0–4 | 2.09 1.58 | 1.70 1.41 |

| Self-harm | Frequency Severity | 34 34 | 0–7 0–6 | 2.53 2.09 | 2.06 1.76 |

| Sleep Problems | Frequency Severity | 28 28 | 0–4 0–4 | 1.43 0.98 | 1.28 0.98 |

| Total | Frequency Severity | 44 44 | 0–27 0–23 | 12.20 9.07 | 7.06 5.65 |

| Men | Woman | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p (Bilateral) | |

| AUTFR | 3.54 | 3.84 | 5.03 | 3.75 | −1.20 | 0.24 |

| AUTGR | 2.69 | 2.98 | 4.41 | 3.24 | −1.643 | 0.11 |

| ESTFR | 2.85 | 2.61 | 4.16 | 3.85 | −1.12 | 0.27 |

| ESTGR | 2.23 | 1.878 | 3.13 | 2.83 | −1.05 | 0.30 |

| AGRFR | 1.38 | 2.02 | 2.66 | 2.12 | −1.85 | 0.07 |

| AGRGR | 1.15 | 1.63 | 2.59 | 1.79 | −2.5 | 0.01 * |

| TOTFR | 7.77 | 7.21 | 11.84 | 8.18 | −1.56 | 0.13 |

| TOTGR | 6.08 | 5.52 | 10.13 | 6.63 | −1.94 | 0.06 |

| Men | Woman | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| IMPFR | 0.77 | 1.09 | 0.97 | 1.12 | −0.55 | 0.59 |

| IMPGR | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.95 | −0.79 | 0.43 |

| ORGFR | -- | -- | 0.16 | 0.52 | −1.09 | 0.28 |

| ORGGR | -- | -- | 0.03 | 0.18 | −0.63 | 0.53 |

| ANSFR | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| ANSGR | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| HUMFR | 0.31 | 0.75 | 0.97 | 1.20 | −1.83 | 0.07 |

| HUMGR | 0.23 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.72 | −1.47 | 0.15 |

| MANFR | 0.31 | 0.75 | 1.31 | 1.23 | −2.74 | 0.01 * |

| MANGR | 0.31 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.81 | −1.63 | 0.11 |

| AUTFR | 3.54 | 2.37 | 3.10 | 2.23 | 0.60 | 0.56 |

| AUTGR | 2.85 | 2.19 | 2.47 | 1.87 | 0.59 | 0.56 |

| ESQFR | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| ESQGR | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| ESTFR | 1.77 | 1.70 | 2.22 | 1.72 | −0.80 | 0.43 |

| ESTGR | 1.15 | 1.35 | 1.75 | 1.41 | −1.30 | 0.20 |

| AGRFR | 2.31 | 2.16 | 2.63 | 2.11 | −0.46 | 0.65 |

| AGRGR | 1.69 | 1.49 | 2.25 | 1.85 | −0.97 | 0.34 |

| PSUFR | 077 | 1.01 | 1.72 | 1.28 | −2.39 | 0.02 * |

| PSUGR | 0.46 | 0.66 | 1.19 | 1.00 | −2.41 | 0.02 * |

| TOTFR | 9.62 | 5.95 | 13.00 | 7.32 | −1.48 | 0.15 |

| TOTGR | 7.23 | 5.07 | 9.81 | 5.78 | −1.403 | 0.17 |

| Loss | Personal | Adaptative | Gross Mot. | Fine Mot. | Motor | Lang. Recep | Lang. Exp | Lan-Guaje | Cogn. | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss | - | −0.423 ** | −0.467 ** | −0.447 ** | −0.451 ** | −0.492 ** | −0.490 ** | −0.540 ** | −0.537 ** | −0.494 ** | −0.491 ** |

| Loss | AUTFR | AUTGR | ESTFR | ESTGR | AGRFR | AGRGR | TOTFR | TOTGR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss | - | 0.300 * | 0.322 * | 0.243 | 0.221 | 0.272 | 0.251 | 0.321 * | 0.319 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bel-Fenellós, C.; Biencinto-López, C.; Sáenz-Rico, B.; Hernández, A.; Sandoval-Talamantes, A.K.; Tenorio-Castaño, J.; Lapunzina, P.; Nevado, J. Cognitive–Behavioral Profile in Pediatric Patients with Syndrome 5p-; Genotype–Phenotype Correlationships. Genes 2023, 14, 1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14081628

Bel-Fenellós C, Biencinto-López C, Sáenz-Rico B, Hernández A, Sandoval-Talamantes AK, Tenorio-Castaño J, Lapunzina P, Nevado J. Cognitive–Behavioral Profile in Pediatric Patients with Syndrome 5p-; Genotype–Phenotype Correlationships. Genes. 2023; 14(8):1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14081628

Chicago/Turabian StyleBel-Fenellós, Cristina, Chantal Biencinto-López, Belén Sáenz-Rico, Adolfo Hernández, Ana Karen Sandoval-Talamantes, Jair Tenorio-Castaño, Pablo Lapunzina, and Julián Nevado. 2023. "Cognitive–Behavioral Profile in Pediatric Patients with Syndrome 5p-; Genotype–Phenotype Correlationships" Genes 14, no. 8: 1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14081628

APA StyleBel-Fenellós, C., Biencinto-López, C., Sáenz-Rico, B., Hernández, A., Sandoval-Talamantes, A. K., Tenorio-Castaño, J., Lapunzina, P., & Nevado, J. (2023). Cognitive–Behavioral Profile in Pediatric Patients with Syndrome 5p-; Genotype–Phenotype Correlationships. Genes, 14(8), 1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14081628