Telomere Length, a New Biomarker of Male (in)Fertility? A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Rationale of Systematic Review of the Literature

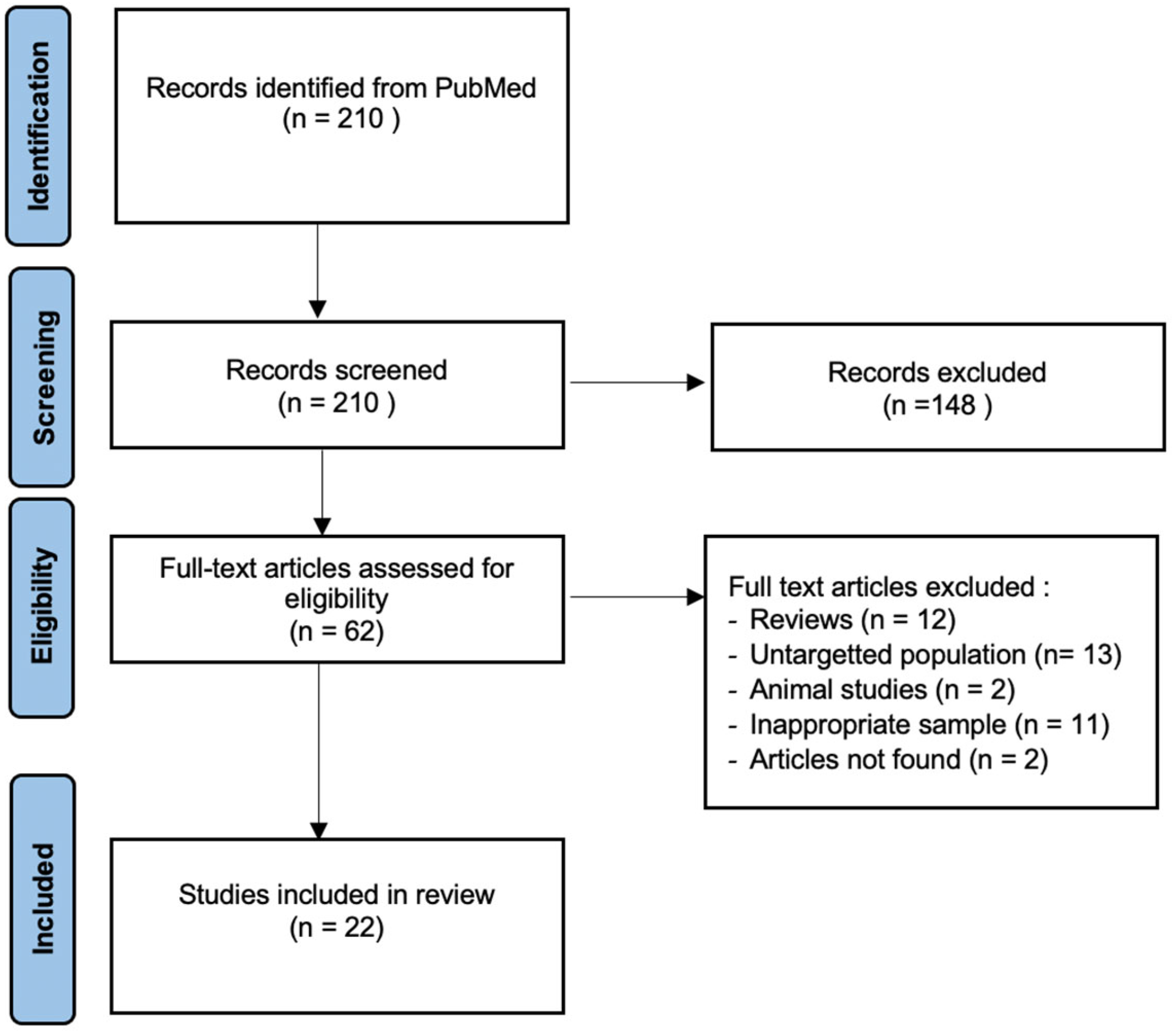

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

3.2. Telomere Length and Semen Parameters

3.3. Telomere Length and Fertility

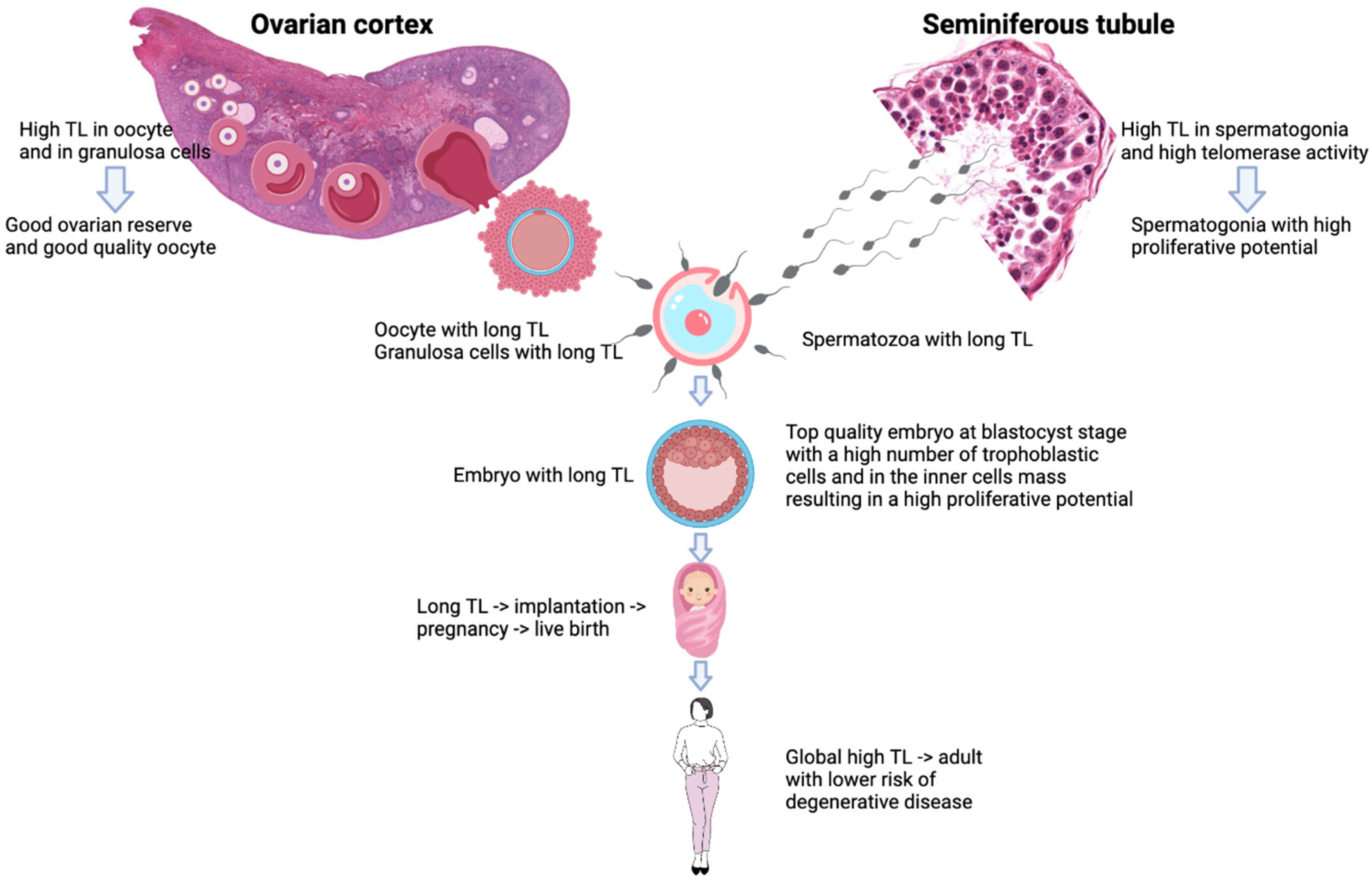

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Agarwal, A.; Mulgund, A.; Hamada, A.; Chyatte, M.R. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.C.; Oliveira, P.F.; Sousa, M. Shedding light into the relevance of telomeres in human reproduction and male factor infertility. Biol. Reprod. 2019, 100, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemes, E.H.; Rawe, Y.V. Sperm pathology: A step beyond descriptive morphology. Origin, characterization and fertility potential of abnormal sperm phenotypes in infertile men. Hum. Reprod. Update 2003, 9, 405–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlin, A.; Foresta, C. New genetic markers for male infertility. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 26, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilagavathi, J.; Venkatesh, S.; Dada, R. Telomere length in reproduction. Andrologia 2013, 45, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, E.H. Telomeres and telomerase: Their mechanisms of action and the effects of altering their functions. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, T. Shelterin: The protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes 2005, 19, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E.; Werbin, H. Defining the molecular mechanisms of human cell immortalization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1991, 1072, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, J.; McGill, N.I.; Lindsey, L.A.; Green, D.K.; Cooke, H.J. In vivo loss of telomeric repeats with age in humans. Mutat. Res. 1991, 256, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E. Telomeres and telomerase: Implications for cancer and aging. Radiat. Res. 2001, 155, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Factor-Litvak, P.; Susser, E.; Kezios, K.; McKeague, I.; Kark, J.D.; Hoffman, M.; Kimura, M.; Wapner, R.; Aviv, A. Leukocyte Telomere Length in Newborns: Implications for the Role of Telomeres in Human Disease. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samassekou, O.; Gadji, M.; Drouin, R.; Yan, J. Sizing the ends: Normal length of human telomeres. Ann. Anat. 2010, 192, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torra-Massana, M.; Barragán, M.; Bellu, E.; Oliva, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Vassena, R. Sperm telomere length in donor samples is not related to ICSI outcome. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achi, M.V.; Ravindranath, N.; Dym, M. Telomere length in male germ cells is inversely correlated with telomerase activity. Biol. Reprod. 2000, 63, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, D.M.; Britt-Compton, B.; Rowson, J.; Amso, N.N.; Gregory, L.; Kipling, D. Telomere instability in the male germline. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlrausch, F.B.; Wang, F.; Chamani, I.; Keefe, D.L. Telomere Shortening and Fusions: A Link to Aneuploidy in Early Human Embryo Development. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2021, 76, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, M.S.; Foresta, C.; Ferlin, A. Telomere length: Lights and shadows on their role in human reproduction. Biol. Reprod. 2019, 100, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.; Pusceddu, I.; März, W.; Herrmann, W. Telomere biology and age-related diseases. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2018, 56, 1210–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngren, K.; Jeanclos, E.; Aviv, H.; Kimura, M.; Stock, J.; Hanna, M.; Skurnick, J.; Bardeguez, A.; Aviv, A. Synchrony in telomere length of the human fetus. Hum. Genet. 1998, 102, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniali, L.; Benetos, A.; Susser, E.; Kark, J.D.; Labat, C.; Kimura, M.; Desai, K.; Granick, M.; Aviv, A. Telomeres shorten at equivalent rates in somatic tissues of adults. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlin, A.; Rampazzo, E.; Rocca, M.S.; Keppel, S.; Frigo, A.C.; De Rossi, A.; Foresta, C. In young men sperm telomere length is related to sperm number and parental age. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 3370–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilagavathi, J.; Kumar, M.; Mishra, S.S.; Venkatesh, S.; Kumar, R.; Dada, R. Analysis of sperm telomere length in men with idiopathic infertility. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 287, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Hartshorne, G.M. Telomere lengths in human pronuclei, oocytes and spermatozoa. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 19, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, D.M.; Kalmbach, K.H.; Wang, F.; Dracxler, R.C.; Seth-Smith, M.L.; Kramer, Y.; Buldo-Licciardi, J.; Kohlrausch, F.B.; Keefe, D.L. A single-cell assay for telomere DNA content shows increasing telomere length heterogeneity, as well as increasing mean telomere length in human spermatozoa with advancing age. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2015, 32, 1685–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, F.; Dai, S.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, W.; Bai, R.; Sun, Y. Sperm telomere length is positively associated with the quality of early embryonic development. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1876–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, W.; Dai, S.; Liu, J.; Bukhari, I.; Xin, H.; Niu, W.; Sun, Y. Processing of semen by density gradient centrifugation selects spermatozoa with longer telomeres for assisted reproduction techniques. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2015, 31, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariati, F.; Jaroudi, S.; Alfarawati, S.; Raberi, A.; Alviggi, C.; Pivonello, R.; Wells, D. Investigation of sperm telomere length as a potential marker of paternal genome integrity and semen quality. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2016, 33, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Kumar, R.; Malhotra, N.; Singh, N.; Dada, R. Mild oxidative stress is beneficial for sperm telomere length maintenance. World J. Methodol. 2016, 6, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, M.S.; Speltra, E.; Menegazzo, M.; Garolla, A.; Foresta, C.; Ferlin, A. Sperm telomere length as a parameter of sperm quality in normozoospermic men. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 1158–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron-Shental, T.; Wiser, A.; Hershko-Klement, A.; Markovitch, O.; Amiel, A.; Berkovitch, A. Sub-fertile sperm cells exemplify telomere dysfunction. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidary, H.; Pouresmaeili, F.; Mirfakhraie, R.; Omrani, M.D.; Ghaedi, H.; Fazeli, Z.; Sayban, S.; Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Azargashb, E.; Shokri, F. An Association Study between Longitudinal Changes of Leukocyte Telomere and the Risk of Azoospermia in a Population of Iranian Infertile Men. Iran Biomed. J. 2018, 22, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, R.; Bosch-Rue, E.; Ribas-Maynou, J.; Alvarez, J.; Brassesco, C.; Amengual, M.J.; Benet, J.; Garcia-Peiró, A.; Brassesco, M. Sperm telomere length in motile sperm selection techniques: A qFISH approach. Andrologia 2018, 50, 12840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Luo, X.; Bai, R.; Zhao, F.; Dai, S.; Li, F.; Zhu, J.; Liu, J.; Niu, W.; Sun, Y. Shorter leukocyte telomere length is associated with risk of nonobstructive azoospermia. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmishonnejad, Z.; Tavalaee, M.; Izadi, T.; Tanhaei, S.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Evaluation of sperm telomere length in infertile men with failed/low fertilization after intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 38, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berneau, S.C.; Shackleton, J.; Nevin, C.; Altakroni, B.; Papadopoulos, G.; Horne, G.; Brison, D.R.; Murgatroyd, C.; Povey, A.C.; Carroll, M. Associations of sperm telomere length with semen parameters, clinical outcomes and lifestyle factors in human normozoospermic samples. Andrology 2020, 8, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmishonnejad, Z.; Zarei-Kheirabadi, F.; Tavalaee, M.; Zarei-Kheirabadi, M.; Zohrabi, D.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Relationship between sperm telomere length and sperm quality in infertile men. Andrologia 2020, 52, 13546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.C.; Oliveira, P.F.; Pinto, S.; Almeida, C.; Pinho, M.J.; Sá, R.; Rocha, E.; Barros, A.; Sousa, M. Discordance between human sperm quality and telomere length following differential gradient separation/swim-up. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 2581–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzadegan, M.; Sadeghi, N.; Tavalaee, M.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Analysis of leukocyte and sperm telomere length in oligozoospermic men. Andrologia 2021, 53, 14204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentiluomo, M.; Luddi, A.; Cingolani, A.; Fornili, M.; Governini, L.; Lucenteforte, E.; Baglietto, L.; Piomboni, P.; Campa, D. Telomere Length and Male Fertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, M.S.; Dusi, L.; Di Nisio, A.; Alviggi, E.; Iussig, B.; Bertelle, S.; De Toni, L.; Garolla, A.; Foresta, C.; Ferlin, A. TERRA: A Novel Biomarker of Embryo Quality and Art Outcome. Genes 2021, 12, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmori, C.; Cordova-Oriz, I.; De Alba, G.; Medrano, M.; Jiménez-Tormo, L.; Polonio, A.M.; Chico-Sordo, L.; Pacheco, A.; García-Velasco, J.A.; Varela, E. Effects of age and oligoasthenozoospermia on telomeres of sperm and blood cells. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2022, 44, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Blasco, M.; Trimarchi, J.; Keefe, D. An essential role for functional telomeres in mouse germ cells during fertilization and early development. Dev. Biol. 2002, 249, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, E.H.; Greider, C.W.; Szostak, J.W. Telomeres and telomerase: The path from maize, Tetrahymena and yeast to human cancer and aging. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, D.; Griffin, D.K. Male fertility, chromosome abnormalities, and nuclear organization. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2011, 133, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.M.; Lewis, S.E.; McKelvey-Martin, V.J.; Thompson, W. A comparison of baseline and induced DNA damage in human spermatozoa from fertile and infertile men, using a modified comet assay. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1996, 2, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zini, A.; Bielecki, R.; Phang, D.; Zenzes, M.T. Correlations between two markers of sperm DNA integrity, DNA denaturation and DNA fragmentation, in fertile and infertile men. Fertil. Steril. 2001, 75, 674–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Ong, C. Detection of oxidative DNA damage in human sperm and its association with sperm function and male infertility. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, R.R.; Schill, W.-B. Sperm preparation for ART. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2003, 1, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, M.M.; Leeton, J.F.; Trounson, A.O.; Wood, C. Successful use of in vitro fertilization for patients with persisting low-quality semen. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1985, 442, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moohan, J.M.; Lindsay, K.S. Spermatozoa selected by a discontinuous Percoll density gradient exhibit better motion characteristics, more hyperactivation, and longer survival than direct swim-up. Fertil. Steril. 1995, 64, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Yang, Q.; Shi, S.; Luo, X.; Sun, Y. Semen preparation methods and sperm telomere length: Density gradient centrifugation versus the swim up procedure. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.-P.; Wright, W.E.; Shay, J.W. Comparison of telomere length measurement methods. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Mulgund, A.; Sharma, R.; Sabanegh, E. Mechanisms of oligozoospermia: An oxidative stress perspective. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2014, 60, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, H.; Cheng, J.W.; Ko, E.Y. Role of reactive oxygen species in male infertility: An updated review of literature. Arab. J. Urol. 2018, 16, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesten, D.M.P.H.J.; de Vos-Houben, J.M.J.; Timmermans, L.; den Hartog, G.J.M.; Bast, A.; Hageman, G.J. Accelerated aging during chronic oxidative stress: A role for PARP-1. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2013, 2013, 680414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.N.; Wu, M.; Bondy, S.C. Telomere shortening during aging: Attenuation by antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents. Mech. Ageing 2017, 164, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecoli, C.; Montano, L.; Borghini, A.; Notari, T.; Guglielmino, A.; Mercuri, A.; Turchi, S.; Andreassi, M.G. Effects of Highly Polluted Environment on Sperm Telomere Length: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.V.; Cruz, D.; Gomes, M.; Correia, B.R.; Freitas, M.J.; Sousa, L.; Silva, V.; Fardilha, M. Study on the short-term effects of increased alcohol and cigarette consumption in healthy young men’s seminal quality. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunc, O.; Bakos, H.W.; Tremellen, K. Impact of body mass index on seminal oxidative stress. Andrologia 2011, 43, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen-Heininger, Y.M.; Mossman, B.T.; Heintz, N.H.; Forman, H.J.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Finkel, T.; Stamler, J.S.; Rhee, S.G.; van der Vliet, A. Redox-based regulation of signal transduction: Principles, pitfalls, and promises. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Wu, S.; Zhang, S.; Ji, G.; Gu, A. Genetic variants in telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and telomerase-associated protein 1 (TEP1) and the risk of male infertility. Gene 2014, 534, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, P.; Du, Y.; Qin, Y.; Chen, Z.J. Impaired telomere length and telomerase activity in peripheral blood leukocytes and granulosa cells in patients with biochemical primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfeir, A.J.; Chai, W.; Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E. Telomere-end processing the terminal nucleotides of human chromosomes. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protsenko, E.; Rehkopf, D.; Prather, A.A.; Epel, E.; Lin, J. Are long telomeres better than short? Relative contributions of genetically predicted telomere length to neoplastic and non-neoplastic disease risk and population health burden. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 0240185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiso, R.; Tamayo, M.; Gosálvez, J.; Meseguer, M.; Garrido, N.; Fernández, J.L. Swim-up procedure selects spermatozoa with longer telomere length. Mutat. Res. 2010, 688, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulos, E.; Fragkiadaki, P.; Kalliora, C.; Fragou, D.; Docea, A.O.; Vakonaki, E.; Tsoukalas, D.; Calina, D.; Buga, A.M.; Georgiadis, G.; et al. The association of female and male infertility with telomere length (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattet, A.J.; Toupance, S.; Thornton, S.N.; Monnin, N.; Guéant, J.L.; Benetos, A.; Koscinski, I. Telomere length in granulosa cells and leukocytes: A potential marker of female fertility? A systematic review of the literature. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toupance, S.; Fattet, A.-J.; Thornton, S.N.; Benetos, A.; Guéant, J.-L.; Koscinski, I. Ovarian Telomerase and Female Fertility. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Studies | Number | Criteria of Patient’s Inclusion | Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferlin et al., 2013 [21] | 61 normozoospermic men 20 idiopathic oligozoospermic men | Volunteers participating in a screening protocol for prevention of andrological disorders | 18–19 |

| Thilagavathi et al., 2013 [22] | 32 men with idiopathic infertility 25 controls | Normal female partner examination Men seeking vasectomy and that have fathered a child < 2 years | N.A. |

| Turner et al., 2013 [23] | 45 unselected men | Men undergoing diagnostic semen analysis | 21–49 |

| Antunes et al., 2015 [24] | 2 oligozoospermic men 1 asthenozoospermic men 1 oligoasthenozoospermic men 6 normozoospermic men | Male partners of couples undergoing ART treatment | 32–48 |

| Yang et al., 2015 [25] | 418 men undergoing their 1st fresh cycle of IVF | Normal chromosome karyotypes, no Y chromosome microdeletions | 30.3 ± 4.0 |

| Yang et al., 2015 [26] | 105 infertile men | Infertile men | 31.2 ± 6.1 |

| Cariati et al., 2016 [27] | 19 oligozoospermic men 54 controls | Men who had requested sperm DNA fragmentation and aneuploidy analyses Normozoospermic men | 31–52 |

| Mishra et al., 2016 [28] | 112 infertile men 102 controls | Male partners of couples with primary infertility Healthy volunteers | 18–45 |

| Rocca et al., 2016 [29] | 100 normozoospermic men | Men referred for semen analysis | 34.0 ± 8.6 |

| Biron-Shental et al., 2018 [30] | 16 sub-fertile men 10 controls | Men undergoing ICSI with normo-ovulatory partners after 1 year of unprotected intercourse Proven fertility in the last year | 29–42 |

| Heidary et al., 2018 [31] | 30 idiopathic nonobstructive azoospermia 30 controls | Men undergoing ICSI Healthy fertile males | 35.4 ± 4.2 |

| Lafuente et al., 2018 [32] | 30 infertile patients | Patients attending the fertility clinic for diagnosis | N.A. |

| Torra Massana et al., 2018 [13] | 60 samples used in a total of 676 ICSI cycles | Donor samples used for ICSI | 24.3 ± 5 |

| Yang et al., 2018 [33] | 247 obstructive azoospermia 349 nonobstructive azoospermia 270 controls | Physical obstruction in the male reproductive system, normal testicular volume, hormone levels, indurated epididymis Spermatogenic dysfunction, abnormal hormone levels, soft testes Sperm counts ≥ 39 × 106/mL, couples with known female factor infertility | 25–38 |

| Darmishonnejad et al., 2019 [34] | 10 infertile men with previous failed/low fertilization 10 controls | Male partners of couples with previous low [<20%] fertilization rates following ICSI within the last 12 months Couples with ≥ 2 live children of the same sex who requested preimplantation genetic testing for family balancing, percentage of fertilization between 50% and 100% | 38.10 ± 4.17 40.11 ± 3.14 |

| Berneau et al., 2020 [35] | 65 normozoospermic men | Male partners of couples undergoing ART treatment | 25–45 |

| Darmishonnejad et al., 2020 [36] | 38 infertile men 19 controls | Infertile men with primary infertility Men with ≥ 1 health child | ≤45 20–50 |

| Lopes et al., 2020 [37] | 73 unselected men 61 patients | Men undergoing ART treatment Patients undergoing embryo transfer cycles | 39.3 ± 4.1 |

| Amirzadegan et al., 2021 [38] | 10 oligozoospermic men 10 controls | Sperm count <15 million/mL | 40.30 ± 3.75 35.46 ± 5.59 |

| Gentiluomo et al., 2021 [39] | 585 unselected men | Men undergoing semen evaluation | 18–59 |

| Rocca et al., 2021 [40] | 4 oligoasthenoteratozoospermic men 31 normozoospermic men 30 controls | Men from couples who underwent their first fresh ICSI treatment Male partners of couples with successful pregnancy within the first 12 months of regular unprotected sexual intercourse | 39 ± 6.4 36.1 ± 6.8 |

| Balmori et al., 2022 [41] | 20 normozoospermic men ≤ 25 years 17 oligoasthenozoospermic men ≤ 25 years 20 normozoospermic men ≥ 40 years 20 oligoasthenozoospermic men ≥ 40 years | Sperm donors ≤ 25 years Men undergoing ART treatment ≥ 40 years | 21.20 ± 2.35 21.44 ± 2.28 43.30 ± 3.43 43.60 ± 3.95 |

| Studies | Samples | Method of Telomere Measurement | Results—Main Findings | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferlin et al., 2013 [21] | Sperm et leukocytes | qPCR | Significant positive correlation between STL and sperm count: rS = 0.33 | 0.0029 * |

| No significant positive correlation between LTL and sperm count: rS = 0.003 | 0.9780 | |||

| Oligozoospermic men: STL = 0.95 ± 0.22 | 0.0001 * | |||

| Normozoospermic men: STL = 1.24 ± 0.25 | ||||

| No difference was observed in LTL between the 2 groups | ||||

| Turner et al., 2013 [23] | Sperm | Q-FISH | No association between semen parameters or male fertility and STL | >0.05 |

| Antunes et al., 2015 [24] | Sperm | qPCR | Normal semen parameters: STL = 16.63 ± 22.29 | 0.0001 * |

| Abnormal semen parameters: STL = 6.92 ± 18.13 | ||||

| Morphologically normal spermatozoa: STL = 12.40 ± 19.77 | 0.991 | |||

| Morphologically abnormal spermatozoa: STL = 13.11 ± 22.56 | ||||

| Yang et al., 2015 [26] | Sperm | qPCR | Significant positive correlation between STL and total sperm number: rp = 0.53 | <0.01 * |

| Yang et al., 2015 [25] | Sperm | qPCR | Significant correlation between STL and sperm count: rp= 0.28 | 0.001 * |

| Cariati et al., 2016 [27] | Sperm | qPCR | Normozoospermic group: STL = 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.0024 * |

| Oligozoospermic group: STL = 0.9 ± 0.1 | ||||

| Significant positive correlation between STL and sperm count: r = 0.325 | 0.006 * | |||

| Rocca et al., 2016 [29] | Sperm | qPCR | STL is positively associated with: | |

| Progressive motility rp = 0.46 | 0.004 * | |||

| Sperm vitality rp = 0.340 | 0.007 * | |||

| Heidary et al., 2018 [31] | Leukocytes | qPCR | Azoospermic men: LTL = 0.54 Fertile men: LTL = 0.84 | <0.05 * |

| Lafuente et al., 2018 [32] | Sperm | Q-FISH | Significant positive correlations between: | |

| STL and sperm concentration: r = −0.308 | 0.049 * | |||

| STL and progressive motility: r = −0.353 | 0.028 * | |||

| STL and immotile sperm: r = 0.446 | 0.007 * | |||

| No significant correlation between STL and sperm DNA fragmentation | >0.05 | |||

| Torra-Massana et al., 2018 [13] | Sperm | qPCR | No relevant correlation between STL and sperm motility | 0.34 |

| Significant correlation between STL and sperm concentration | 0.03 * | |||

| Yang et al., 2018 [33] | Leukocytes | qPCR | Controls + OA: LTL = 0.96; NOA: LTL = 0,81 [OR 0.172; 95% CI 0.107–0.279] No significant difference between OA and normozoospermic controls | <0.001 * |

| Lopes et al., 2020 [37] | Selected sperm | qPCR | No relation between STL and total sperm count | 0.590 |

| No relation between STL and sperm motility | 0.354 | |||

| No relation between STL and normal morphology | 0.169 | |||

| Amirzadegan et al., 2021 [38] | Leukocytes and sperm | qPCR | Oligozoospermic men: LTL = 0.61 ± 0.30 | 0.01 * |

| Fertile men: LTL = 1.22 ± 0.71 | ||||

| Oligozoospermic men: STL = 0.65 ± 0.25 | 0.02 * | |||

| Fertile men: STL = 1.04 ± 0.46 | ||||

| Gentiluomo et al., 2021 [39] | Sperm | qPCR | No significant association between STL and sperm parameters | >0.05 |

| Balmori et al., 2022 [41] | Sperm and PBMC | Q-FISH | In NZ ≤ 25 years, significant positive correlation between STL and | |

| Sperm count: r = 0.641 | 0.009 * | |||

| Motility: r = 0.639 | 0.007 * | |||

| OAZ men ≤ 25 years: TL shorter than NZ men ≤ 25 years; NZ men ≥ 40 years; | 0.0081 * | |||

| OAZ men ≥ 40 years | 0.0116 * | |||

| 0.009 * |

| Studies | Samples | Method of Telomere Measurement | Results—Main Findings | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical criteria of fertility | ||||

| Thilagavathi et al., 2013 [22] | Sperm | qPCR | Infertile men: STL = 0.674 ± 0.028 | <0.005 * |

| Controls: STL = 0.699 ± 0.030 | ||||

| Turner et al., 2013 [23] | Sperm | Q-FISH | No association between male fertility and STL | >0.05 |

| Yang et al., 2015 [25] | Selected sperm | qPCR | No significant association between STL and clinical pregnancy rates | 0.90 |

| Cariati et al., 2016 [27] | Sperm | qPCR | STL between 0.2–2.0: pregnancy rate = 35.7% | 0.04 * |

| STL < 0.2 or > 2.0: pregnancy rate = 0.0% | ||||

| Mishra et al., 2016 [28] | Sperm | qPCR | Infertile men: STL = 0.609 ± 0.15Controls: STL = 0.789 ± 0.060 | <0.0001 * |

| Biron-Shental et al., 2018 [30] | Sperm | FISH | Sub-fertile sperm: STL = 0.6 ± 1.2%Fertile sperm: STL = 3.3 ± 3.1% | <0.005 * |

| Lafuente et al., 2018 [32] | Selected sperm | Q-FISH | Previously achieved a natural clinical pregnancy STL = 26.17 ± 8.20 kb | 0.024 * |

| Couples who had never conceived STL = 19.50 ± 5.05 kb | ||||

| Torra-Massana et al., 2018 [13] | Thawed and selected sperm | qPCR | No significant effect of STL on reproductive outcomes: | |

| Biochemical pregnancy rate | 0.411 | |||

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 0.986 | |||

| Ongoing pregnancy rate | 0.769 | |||

| Live birth rate | 0.595 | |||

| Darmishonnejad et al., 2019 [34] | Sperm and leukocytes | qPCR | Infertile men: STL = 0.74 ± 0.15 | <0.05 * |

| Fertile men: STL = 1.24 ± 0.18 | ||||

| Relative telomere length in leukocytes was no different between the two groups | ||||

| Berneau et al., 2020 [35] | Selected sperm | qPCR | Clinical pregnancy: STL = 1.026 ± 0.013 | 0.188 |

| No clinical pregnancy: STL = 0.995 ± 0.016 | ||||

| Darmishonnejad et al., 2020 [36] | Sperm and leukocytes | qPCR | Fertile men: STL = 1.09 ± 0.13 | 0.002 * |

| Infertile men: STL = 0.61 ± 0.07 | ||||

| Fertile men: LTL = 1.1 ± 0.14 | 0.1 | |||

| Infertile men: LTL = 0.76 ± 0.07 | ||||

| Rocca et al., 2021 [40] | Sperm | qPCR | ART group: STL = 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.02 * |

| Control group: STL = 1.2 ± 0.6 | ||||

| Lopes et al., 2020 [37] | Selected sperm | qPCR | No relation between STL and time of infertility | 0.556 |

| No influence of relative STL on implantation rate | 0.508 | |||

| ART embryo criteria | ||||

| Yang et al., 2015 [25] | Selected sperm | qPCR | STL is positively associated with the good embryo quality rate | <0.001 * |

| STL is positively associated with the transplantable embryo rate | <0.001 * | |||

| No association between STL and fertilization rate | 0.49 | |||

| Torra-Massana et al., 2018 [13] | Thawed and selected sperm | qPCR | No significant correlation between STL and the average score of embryo morphology | 0.08 |

| No significant correlation between STL and the fertilization rate | 0.35 | |||

| Darmishonneiad et al., 2019 [34] | Sperm | qPCR | Positive significant correlation between fertilization rate and STL | 0.007 * |

| Berneau et al., 2020 [35] | Selected sperm | qPCR | STL is positively correlated with fertilization rate | 0.004 * |

| No significant association between STL and embryo cleavage rate | >0.05 | |||

| Lopes et al., 2020 [37] | Selected sperm | qPCR | No influence of relative STL in fertilization rate | 0.411 |

| No influence of relative STL on embryo cleavage rate | 0.900 | |||

| No influence of relative STL on AB embryo grade rate | 0.123 | |||

| No influence of relative STL on embryo fragmentation | 0.136 | |||

| No influence of relative STL on blastocyst formation rate | 0.836 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fattet, A.-J.; Chaillot, M.; Koscinski, I. Telomere Length, a New Biomarker of Male (in)Fertility? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Genes 2023, 14, 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14020425

Fattet A-J, Chaillot M, Koscinski I. Telomere Length, a New Biomarker of Male (in)Fertility? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Genes. 2023; 14(2):425. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14020425

Chicago/Turabian StyleFattet, Anne-Julie, Maxime Chaillot, and Isabelle Koscinski. 2023. "Telomere Length, a New Biomarker of Male (in)Fertility? A Systematic Review of the Literature" Genes 14, no. 2: 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14020425

APA StyleFattet, A.-J., Chaillot, M., & Koscinski, I. (2023). Telomere Length, a New Biomarker of Male (in)Fertility? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Genes, 14(2), 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14020425