Satisfaction and Quality of Life of Healthy and Unilateral Diseased BRCA1/2 Pathogenic Variant Carriers after Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Using the BREAST-Q Questionnaire

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

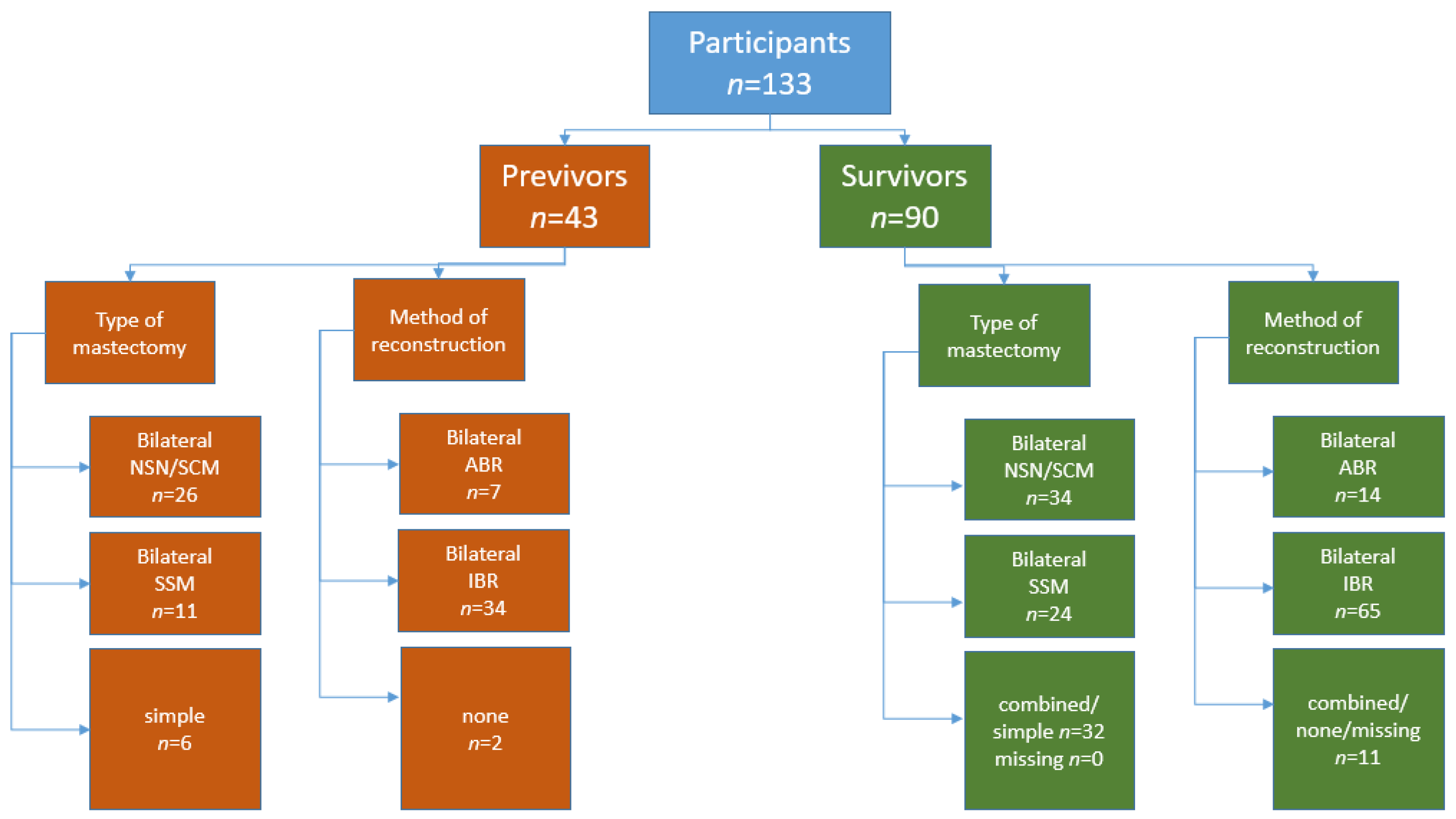

3.1. Overall Cohort

3.2. Previvors

3.3. Survivors

3.3.1. Tumor Type and Therapy

3.3.2. Radiation

3.3.3. Mastectomy and Reconstruction

3.3.4. Ovarian Cancer

3.4. Overall Results: BREAST-Q Mastectomy and Reconstruction Module

3.4.1. Satisfaction Scores within the Whole Cohort

3.4.2. Satisfaction Scores According to the Indication for Surgery: Comparison between Previvors and Survivors

3.4.3. Comparison of Scores among Previvors According to the Type of Mastectomy and Type of Reconstruction

3.4.4. Comparison among Survivors According to the Type of Mastectomy and Type of Reconstruction

3.5. Influence of Tumor Therapy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graeser, M.K.; Engel, C.; Rhiem, K.; Gadzicki, D.; Bick, U.; Kast, K.; Froster, U.G.; Schlehe, B.; Bechtold, A.; Arnold, N.; et al. Contralateral breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5887–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhiem, K.; Engel, C.; Graeser, M.; Zachariae, S.; Kast, K.; Kiechle, M.; Ditsch, N.; Janni, W.; Mundhenke, C.; Golatta, M.; et al. The risk of contralateral breast cancer in patients from BRCA1/2 negative high risk families as compared to patients from BRCA1 or BRCA2 positive families: A retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; Phillips, K.A.; Mooij, T.M.; Roos-Blom, M.J.; Jervis, S.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Milne, R.L.; Andrieu, N.; et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA 2017, 317, 2402–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; You, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yu, B.; Xu, T.; Cai, H.; Zou, Q. Effectiveness of Prophylactic Surgeries in BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 3971–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Felice, F.; Marchetti, C.; Musella, A.; Palaia, I.; Perniola, G.; Musio, D.; Muzii, L.; Tombolini, V.; Benedetti Panici, P. Bilateral risk-reduction mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: A meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 2876–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemskerk-Gerritsen, B.A.; Rookus, M.A.; Aalfs, C.M.; Ausems, M.G.; Collee, J.M.; Jansen, L.; Kets, C.M.; Keymeulen, K.B.; Koppert, L.B.; Meijers-Heijboer, H.E.; et al. Improved overall survival after contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with a history of unilateral breast cancer: A prospective analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemskerk-Gerritsen, B.A.M.; Jager, A.; Koppert, L.B.; Obdeijn, A.I.; Collee, M.; Meijers-Heijboer, H.E.J.; Jenner, D.J.; Oldenburg, H.S.A.; van Engelen, K.; de Vries, J.; et al. Survival after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy in healthy BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 177, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halsted, W.S.I. The Results of Operations for the Cure of Cancer of the Breast Performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital from June, 1889, to January, 1894. Ann. Surg. 1894, 20, 497–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.D.; Gopman, J.M.; Salzberg, C.A. The evolution of mastectomy surgical technique: From mutilation to medicine. Gland Surg. 2018, 7, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, E. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in screening women at high risk of breast cancer. Top. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2008, 19, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, X.A.; Houssami, N.; Obdeijn, I.M.; Warner, E.; Sardanelli, F.; Leach, M.O.; Riedl, C.C.; Trop, I.; Tilanus-Linthorst, M.M.; Mandel, R.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging improves breast screening sensitivity in BRCA mutation carriers age >/= 50 years: Evidence from an individual patient data meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, U.; Engel, C.; Krug, B.; Heindel, W.; Fallenberg, E.M.; Rhiem, K.; Maintz, D.; Golatta, M.; Speiser, D.; Rjosk-Dendorfer, D.; et al. High-risk breast cancer surveillance with MRI: 10-year experience from the German consortium for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 175, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, D.G.; Kesavan, N.; Lim, Y.; Gadde, S.; Hurley, E.; Massat, N.J.; Maxwell, A.J.; Ingham, S.; Eeles, R.; Leach, M.O.; et al. MRI breast screening in high-risk women: Cancer detection and survival analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 145, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltahir, Y.; Werners, L.; Dreise, M.M.; van Emmichoven, I.A.Z.; Jansen, L.; Werker, P.M.N.; de Bock, G.H. Quality-of-life outcomes between mastectomy alone and breast reconstruction: Comparison of patient-reported BREAST-Q and other health-related quality-of-life measures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 132, 201e–209e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusic, A.L.; Klassen, A.F.; Scott, A.M.; Klok, J.A.; Cordeiro, P.G.; Cano, S.J. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: The BREAST-Q. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 124, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusic, A.L.; Klassen, A.F.; Snell, L.; Cano, S.J.; McCarthy, C.; Scott, A.; Cemal, Y.; Rubin, L.R.; Cordeiro, P.G. Measuring and managing patient expectations for breast reconstruction: Impact on quality of life and patient satisfaction. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2012, 12, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapdor, R.; Weiß, C.; Kuehnle, E.; Kohls, F.; von Ehr, J.; Philippeit, A.; Hille-Betz, U. Quality of Life after Bilateral and Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy with Implant Reconstruction. Breast Care 2020, 15, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.; Meisel, C.; Grubling, N.; Petzold, A.; Wimberger, P.; Kast, K. Patient-Reported Satisfaction after Prophylactic Operations of the Breast. Breast Care 2019, 14, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razdan, S.N.; Patel, V.; Jewell, S.; McCarthy, C.M. Quality of life among patients after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy: A systematic review of patient-reported outcomes. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 1409–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.M.; Hamill, J.B.; Kim, H.M.; Qi, J.; Wilkins, E.; Pusic, A.L. Impact of Bilateral Prophylactic Mastectomy and Immediate Reconstruction on Health-Related Quality of Life in Women at High Risk for Breast Carcinoma: Results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 2502–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kast, K.; Rhiem, K.; Wappenschmidt, B.; Hahnen, E.; Hauke, J.; Bluemcke, B.; Zarghooni, V.; Herold, N.; Ditsch, N.; Kiechle, M.; et al. Prevalence of BRCA1/2 germline mutations in 21 401 families with breast and ovarian cancer. J. Med. Genet. 2016, 53, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plon, S.E.; Eccles, D.M.; Easton, D.; Foulkes, W.D.; Genuardi, M.; Greenblatt, M.S.; Hogervorst, F.B.; Hoogerbrugge, N.; Spurdle, A.B.; Tavtigian, S.V.; et al. Sequence variant classification and reporting: Recommendations for improving the interpretation of cancer susceptibility genetic test results. Hum. Mutat. 2008, 29, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurdle, A.B.; Healey, S.; Devereau, A.; Hogervorst, F.B.; Monteiro, A.N.; Nathanson, K.L.; Radice, P.; Stoppa-Lyonnet, D.; Tavtigian, S.; Wappenschmidt, B.; et al. ENIGMA--evidence-based network for the interpretation of germline mutant alleles: An international initiative to evaluate risk and clinical significance associated with sequence variation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Z.; Turnbull, A.; Yost, S.; Seal, S.; Mahamdallie, S.; Poyastro-Pearson, E.; Warren-Perry, M.; Eccleston, A.; Tan, M.M.; Teo, S.H.; et al. Evaluation of Cancer-Based Criteria for Use in Mainstream BRCA1 and BRCA2 Genetic Testing in Patients With Breast Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e194428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Evans, T.G.; Bailey, D.; Lewis, M.H.; Gower-Thomas, K.; Murray, A. Uptake of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA gene carriers in Wales, UK. Breast J. 2018, 24, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, S.; Vetter, L.; Keller, M.; Bruckner, T.; Golatta, M.; Eismann, S.; Dikow, N.; Evers, C.; Sohn, C.; Heil, J. Women at familial risk of breast cancer electing for prophylactic mastectomy: Frequencies, procedures, and decision-making characteristics. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 295, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, N.N.; Hodson, J.; Chatterjee, S.; Gandhi, A.; Wisely, J.; Harvey, J.; Highton, L.; Murphy, J.; Barnes, N.; Johnson, R.; et al. The Angelina Jolie effect: Contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy trends in patients at increased risk of breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, W.A.; Mundy, L.R.; Ballard, T.N.; Klassen, A.; Cano, S.J.; Browne, J.; Pusic, A.L. The BREAST-Q in surgical research: A review of the literature 2009–2015. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2016, 69, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyserkani, N.M.; Jørgensen, M.G.; Tabatabaeifar, S.; Damsgaard, T.; Sørensen, J.A. Autologous versus implant-based breast reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Breast-Q patient-reported outcomes. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2020, 73, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kautz-Freimuth, S.; Redaèlli, M.; Rhiem, K.; Vodermaier, A.; Krassuski, L.; Nicolai, K.; Schnepper, M.; Kuboth, V.; Dick, J.; Vennedey, V.; et al. Development of decision aids for female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers in Germany to support preference-sensitive decision-making. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, A.F.; Balneaves, L.G.; Bottorff, J.L. Women’s decision making about risk-reducing strategies in the context of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: A systematic review. J. Genet Couns. 2009, 18, 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, M.H.; Schaid, D.J.; Sellers, T.A.; Slezak, J.M.; Arnold, P.G.; Woods, J.E.; Petty, P.M.; Johnson, J.L.; Sitta, D.L.; McDonnell, S.K.; et al. Long-term satisfaction and psychological and social function following bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. JAMA 2000, 284, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Egdom, L.S.E.; de Kock, M.A.; Apon, I.; Mureau, M.A.M.; Verhoef, C.; Hazelzet, J.A.; Koppert, L.B. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures may optimize shared decision-making for cancer risk management in BRCA mutation carriers. Breast Cancer 2020, 27, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanoff, A.; Zabor, E.C.; Stempel, M.; Sacchini, V.; Pusic, A.; Morrow, M. A Comparison of Patient-Reported Outcomes After Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Conventional Mastectomy with Reconstruction. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 2909–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Verschuer, V.M.; Mureau, M.A.; Gopie, J.P.; Vos, E.L.; Verhoef, C.; Menke-Pluijmers, M.B.; Koppert, L.B. Patient Satisfaction and Nipple-Areola Sensitivity After Bilateral Prophylactic Mastectomy and Immediate Implant Breast Reconstruction in a High Breast Cancer Risk Population: Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy Versus Skin-Sparing Mastectomy. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016, 77, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon-Flannery, K.; DeStefano, L.M.; De La Cruz, L.M.; Fisher, C.S.; Lin, L.Y.; Coffua, L.S.; Mustafa, R.E.; Sataloff, D.M.; Tchou, J.C.; Brooks, A.D. Quality of life and sexual well-being after nipple sparing mastectomy: A matched comparison of patients using the breast Q. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 118, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, K.I.; Khan, H.; Levine, M. Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: 14. The role of hormone replacement therapy in women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer. Cmaj 2002, 166, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sabawi, B.; Ho, A.L.; Sosin, M.; Patel, K.M. Patient-centered outcomes of breast reconstruction in the setting of post-mastectomy radiotherapy: A comprehensive review of the literature. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2017, 70, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopie, J.P.; Mureau, M.A.; Seynaeve, C.; Ter Kuile, M.M.; Menke-Pluymers, M.B.; Timman, R.; Tibben, A. Body image issues after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy with breast reconstruction in healthy women at risk for hereditary breast cancer. Fam. Cancer 2013, 12, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.K.; Olawoyin, O.; Chouairi, F.; Duy, P.Q.; Mets, E.J.; Gabrick, K.S.; Le, N.K.; Avraham, T.; Alperovich, M. Worse overall health status negatively impacts satisfaction with breast reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2020, 73, 2056–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazzazi, F.; Haggie, R.; Forouhi, P.; Kazzazi, N.; Wyld, L.; Malata, C.M. A comparison of patient satisfaction (using the BREAST-Q questionnaire) with bilateral breast reconstruction following risk-reducing or therapeutic mastectomy. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2018, 71, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffers, L.; Reid, J.; Fitzsimons, D.; Morrison, P.J.; Dempster, M. Interventions to improve psychosocial well-being in female BRCA-mutation carriers following risk-reducing surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, Cd012894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.L.; Klassen, A.F.; Cano, S.; Scott, A.M.; Pusic, A.L. Optimizing patient-centered care in breast reconstruction: The importance of preoperative information and patient-physician communication. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 132, 212e–220e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Previvors n = 43 | Survivors n = 90 | All n = 133 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 pV carriers | 25 | 60 | 85 |

| BRCA2 pV carriers | 18 | 30 | 48 |

| Total | 43 | 90 | 133 |

| Age at BC (years) range (years) | 39.6 ± 8 years 20–58 | ||

| Age at last RRM surgery (years) range (years) | 36.4 ± 7.9 23–51 | 41.9 ± 8.2 21–60 | 40.1 ± 8.5 21–60 |

| Follow-up time after last surgery (months) | 43.3 ± 33.3 | 47.8 ± 50.2 | 46.3 ± 45.3 |

| Method of mastectomy | |||

| Bilateral NSM/SCM | 26 | 8 | 32 |

| Bilateral SSM | 11 | 5 | 16 |

| Combined/missing data on RRM | 6 | 77 | 83 |

| total | 43 | 90 | 133 |

| Method of reconstruction | |||

| Bilateral ABR | 7 | 14 | 21 |

| Bilateral IBR | 34 | 65 | 94 |

| Combined methods/no reconstruction/missing data on RRM | 2 | 11 | 13 |

| Total | 43 | 90 | 133 |

| Age at RSSO (years) n | 41.4 ± 6.2 n = 12 | 43.9 ± 6.41 n = 36 | 43.4 ± 6.5 n = 48 |

| Phenotype | Survivors n | Proportion of 90 Survivors (in%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left side Right side | 52 38 | 57.8 42.2 | |

| Tumor Stadium | cT1c | 1 | |

| cT2 | 2 | ||

| pT1 | 53 | 58.9 | |

| pT2 | 20 | 22.2 | |

| pT3 | 2 | 2.2 | |

| T0 | 12 | 13.3 | |

| Missing | 3 | 3.3 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | |

| Nodal Status | cN0 | 1 | 1.1 |

| cN1a | 1 | 1.1 | |

| pN0 | 63 | 70 | |

| pN1 (1a, 1b) | 20 | 22.2 | |

| pN2 | 3 | 3.3 | |

| pN3 | 1 | 1.1 | |

| pNx | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | |

| Immunohistochemistry | ER pos | 38 | 42.2 |

| ER neg | 51 | 57.6 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | |

| Her2 pos | 9 | 10 | |

| Her2 neg | 78 | 86.7 | |

| Missing | 3 | 3.3 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | |

| TNBC | 49 | 54.4 | |

| TNBC in BRCA1 pV | 42 | - | |

| TNBC in BRCA2 pV | 7 | - | |

| Systemic treatment | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 35 | 38.9 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 46 | 51.1 | |

| No chemotherapy | 9 | 10 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | |

| Endocrine therapy | 32 | 35.6 | |

| No endocrine therapy | 58 | 64.6 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | |

| Radiation | Adjuvant radiation | 36 | 40 |

| No adjuvant radiation | 54 | 60 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | |

| Adjuvant radiation after initial BCT | 29/36 |

| All n | Previvor n | Survivor n | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with breasts | 66.9 ± 17.8 119 | 71.2 ± 16.6 38 | 64.8 ± 18.1 81 | 0.069 |

| Satisfaction with outcome | 78.3 ± 19.4 119 | 80.6 ± 20.1 39 | 77.2 ± 18.9 80 | 0.0377 |

| Psychosocial well-being | 73.7 ± 20.9 119 | 80.4 ± 19.5 39 | 70.5 ± 21.0 80 | 0.015 |

| Sexual well-being | 57.9 ± 21.7 112 | 67.1 ± 20.8 36 | 53.6 ± 20.9 76 | 0.002 |

| Physical well-being chest | 68.3 ± 15.9 121 | 76.1 ± 12.4 39 | 64.7 ± 16.2 82 | 0.000 |

| Physical well-being abdomen | 64.8 ± 25.9 29 | 55.0 ± 36.4 5 | 66.8 ± 23.5 24 | 0.361 |

| Satisfaction with nipples | 58.2 ± 28.0 25 | 58.7 ± 17.1 6 | 58.0 ± 31.1 19 | 0.964 |

| Satisfaction with information | 71.2 ± 17.4 120 | 76.9 ± 16.1 38 | 68.6 ± 17.4 82 | 0.014 |

| Satisfaction with surgeon | 86.9 ± 16.3 120 | 90.5 ± 14.2 39 | 82.2 ± 17.1 80 | 0.101 |

| Satisfaction with medical staff | 85.9 ± 19.9 118 | 87.7±18.3 38 | 85.0±20.7 80 | 0.505 |

| Satisfaction with office staff | 83.4 ± 20.0 117 | 84.6 ± 21.4 38 | 82.9 ± 20.6 79 | 0.670 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herold, N.; Hellmich, M.; Lichtenheldt, F.; Ataseven, B.; Hillebrand, V.; Wappenschmidt, B.; Schmutzler, R.K.; Rhiem, K. Satisfaction and Quality of Life of Healthy and Unilateral Diseased BRCA1/2 Pathogenic Variant Carriers after Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Using the BREAST-Q Questionnaire. Genes 2022, 13, 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13081357

Herold N, Hellmich M, Lichtenheldt F, Ataseven B, Hillebrand V, Wappenschmidt B, Schmutzler RK, Rhiem K. Satisfaction and Quality of Life of Healthy and Unilateral Diseased BRCA1/2 Pathogenic Variant Carriers after Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Using the BREAST-Q Questionnaire. Genes. 2022; 13(8):1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13081357

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerold, Natalie, Martin Hellmich, Frank Lichtenheldt, Beyhan Ataseven, Vanessa Hillebrand, Barbara Wappenschmidt, Rita Katharina Schmutzler, and Kerstin Rhiem. 2022. "Satisfaction and Quality of Life of Healthy and Unilateral Diseased BRCA1/2 Pathogenic Variant Carriers after Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Using the BREAST-Q Questionnaire" Genes 13, no. 8: 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13081357

APA StyleHerold, N., Hellmich, M., Lichtenheldt, F., Ataseven, B., Hillebrand, V., Wappenschmidt, B., Schmutzler, R. K., & Rhiem, K. (2022). Satisfaction and Quality of Life of Healthy and Unilateral Diseased BRCA1/2 Pathogenic Variant Carriers after Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Using the BREAST-Q Questionnaire. Genes, 13(8), 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13081357