Mutation Patterns of Human SARS-CoV-2 and Bat RaTG13 Coronavirus Genomes Are Strongly Biased Towards C>U Transitions, Indicating Rapid Evolution in Their Hosts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Source of Sequences

2.2. Identification of Sequence Variants

2.3. Analysis of Data

3. Results

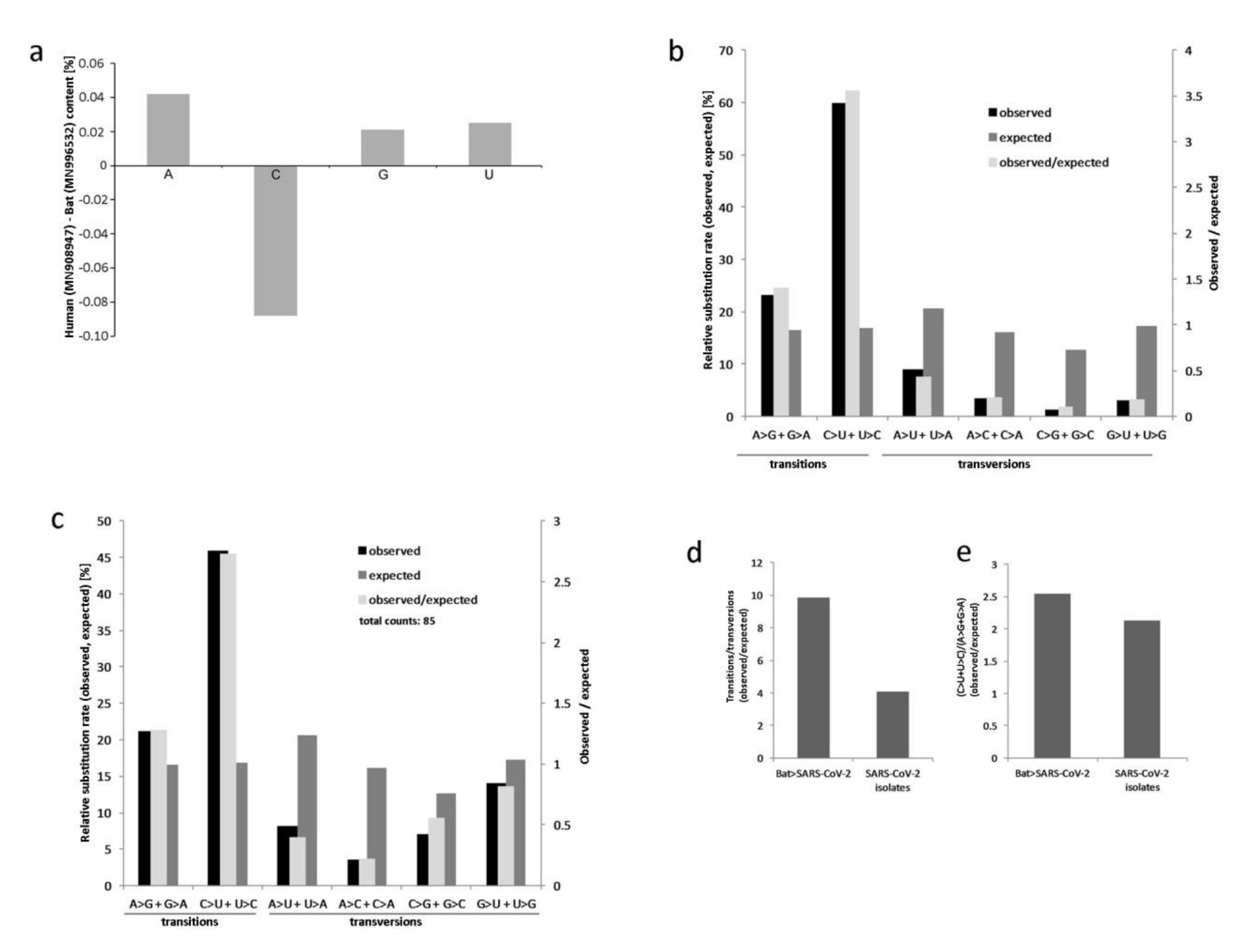

3.1. Sequence Comparison and SNP Analyses of Related SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 Genomes

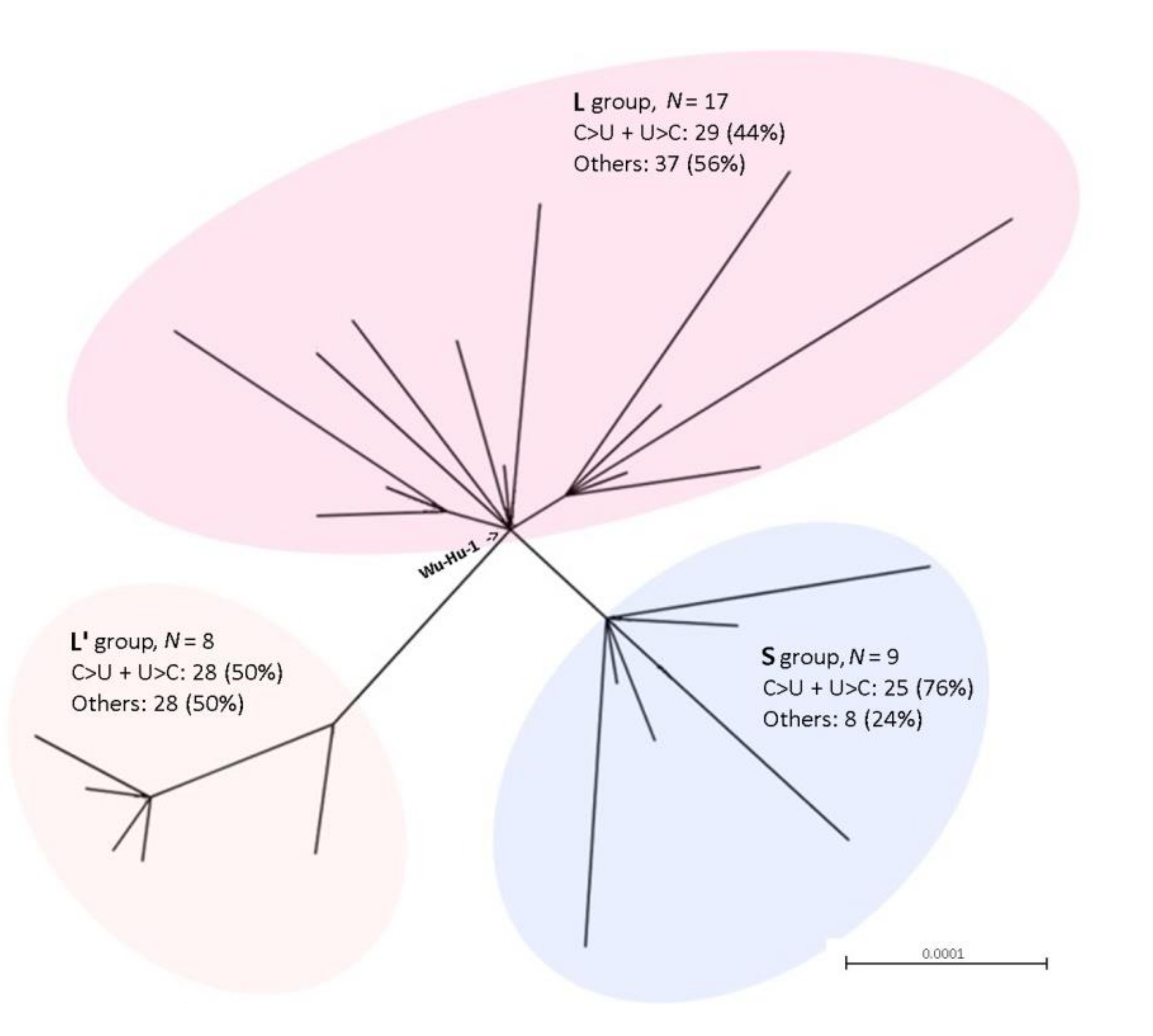

3.2. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Virus Variants

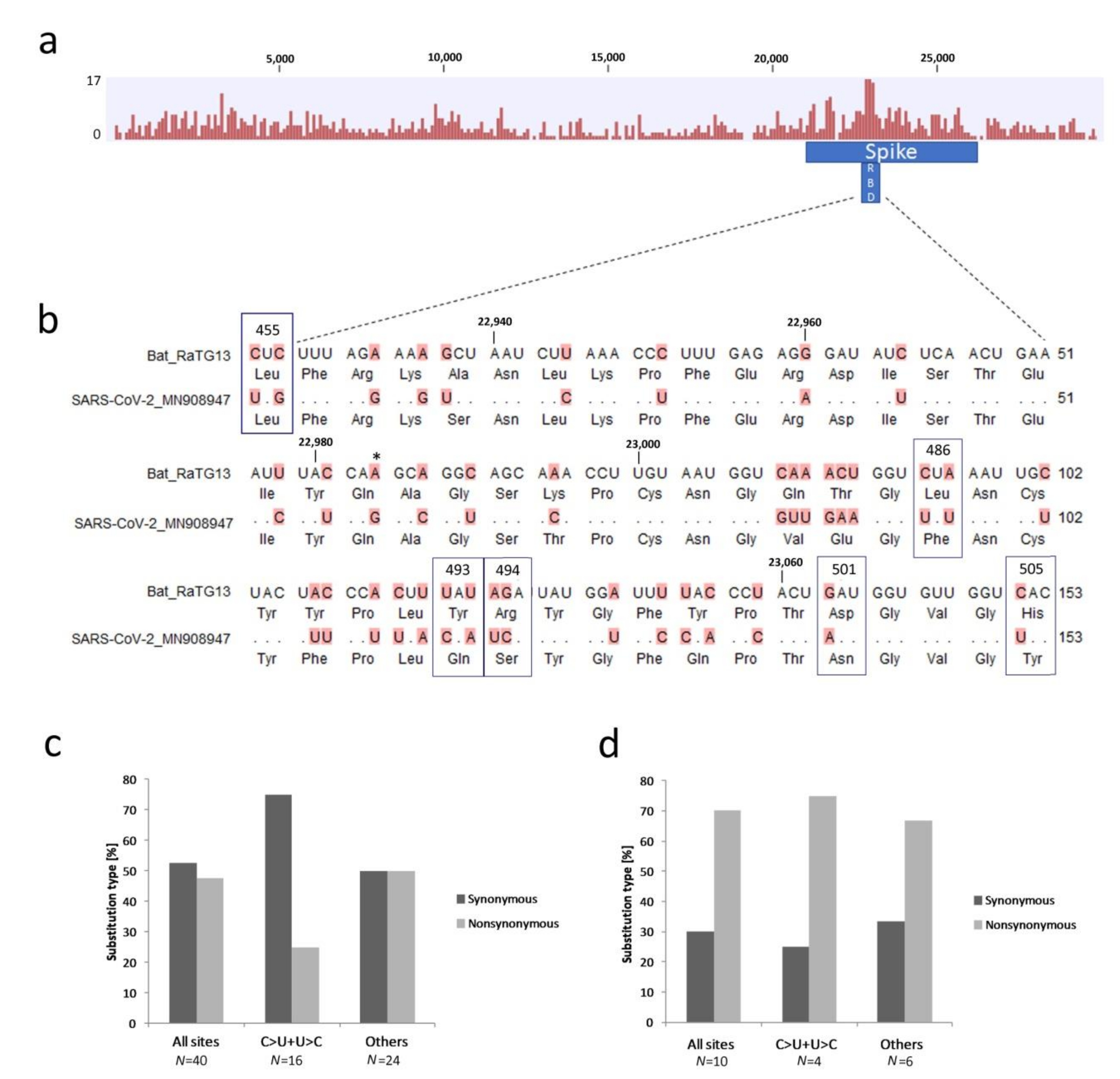

3.3. Variation in the Surface Glycoprotein (Spike) Subregion

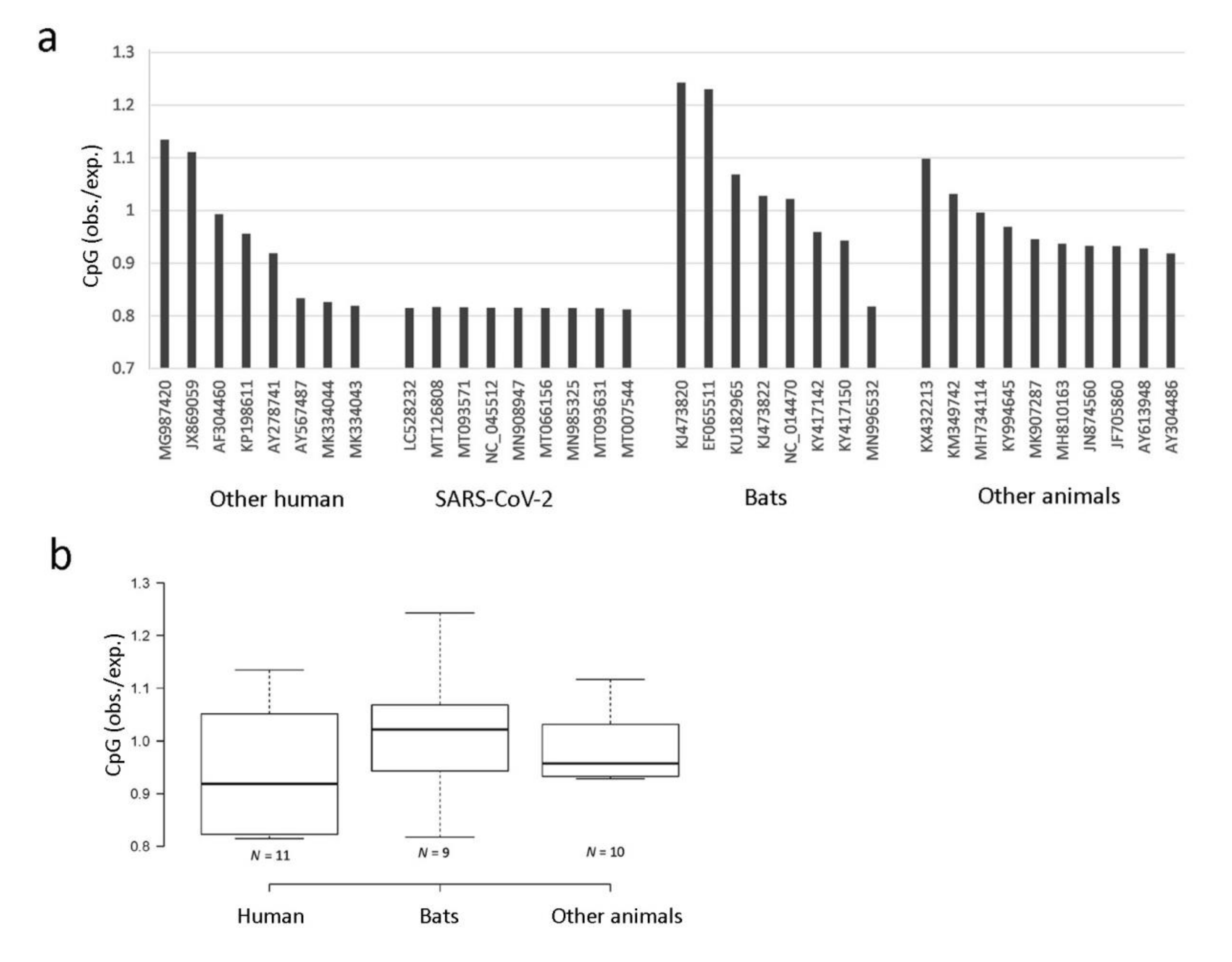

3.4. CpG Depletion Analysis in Coronaviruses

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution of C-Deamination Events to SARS-CoV-2 Mutability

4.2. Relationship between SARS-CoV-2 Mutability and CpG Depletion

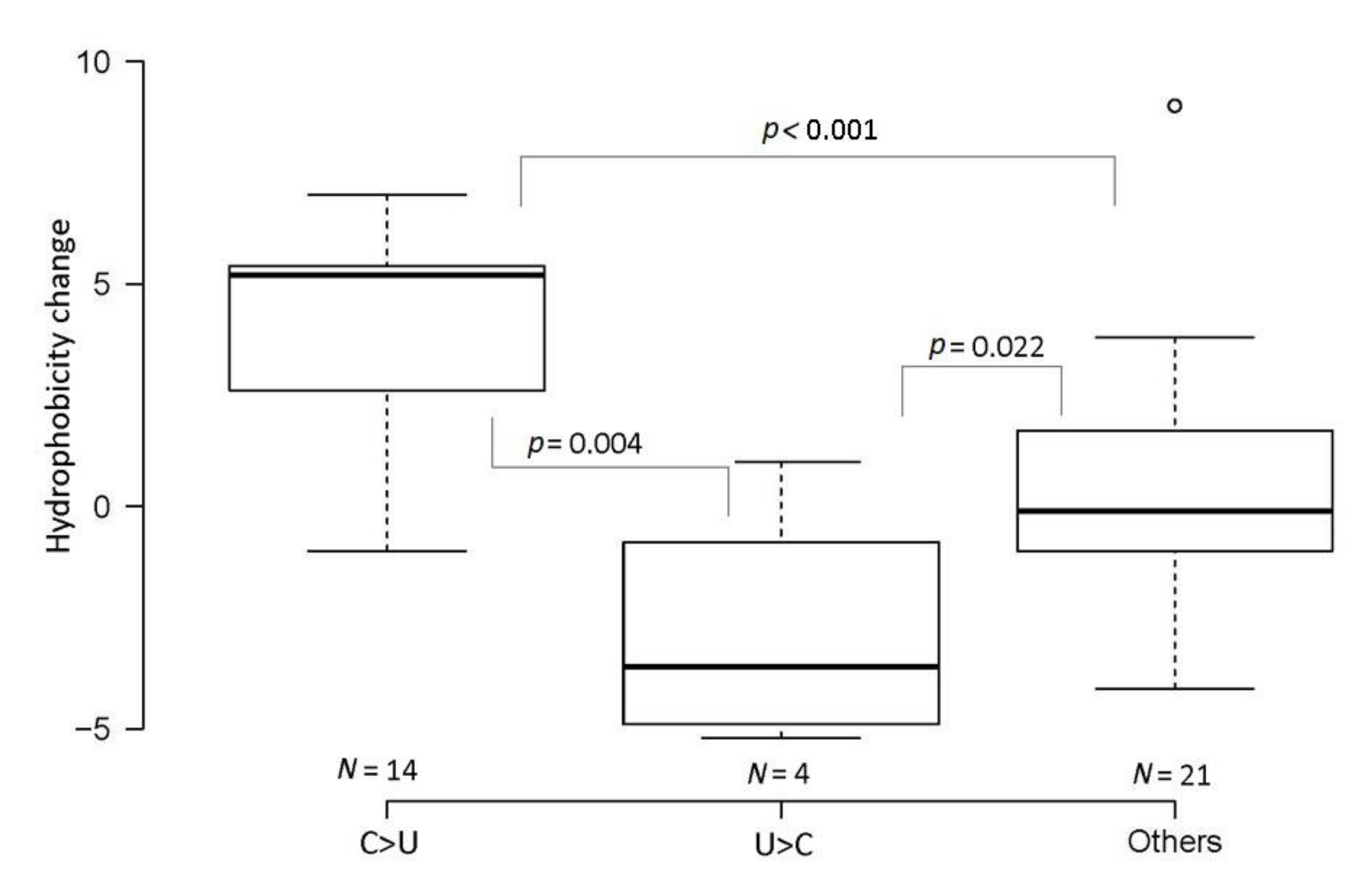

4.3. Do C>U Transitions Have Adaptive Value?

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandeel, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Fayez, M.; Al-Nazawi, M. From SARS and MERS CoVs to SARS-CoV-2: Moving toward more biased codon usage in viral structural and nonstructural genes. J. Med. Virol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Shang, J.; Graham, R.; Baric, R.S.; Li, F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: An analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z. Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Biol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederico, L.A.; Kunkel, T.A.; Shaw, B.R. Cytosine deamination in mismatched base pairs. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 6523–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, A.; Penny, D.; Sjoberg, B.M. Confounded cytosine! Tinkering and the evolution of DNA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, K.; Bernardi, G. Cytosine methylation and CpG, TpG (CpA) and TpA frequencies. Gene 2004, 333, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Cheng, J.B.; Li, D.; Xie, M.; Hong, C.; Maire, C.L.; Ligon, K.L.; Hirst, M.; Marra, M.A.; Costello, J.F.; et al. Estimating absolute methylation levels at single-CpG resolution from methylation enrichment and restriction enzyme sequencing methods. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 1541–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kypr, J.; Mrazek, J.; Reich, J. Nucleotide composition bias and CpG dinucleotide content in the genomes of HIV and HTLV 1/2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1989, 1009, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Virk, N.; Chen, W.; Ji, S.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X. CpG usage in RNA viruses: Data and hypotheses. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, M.; Samal, J.; Kandpal, M.; Vasaikar, S.; Biswas, B.; Gomes, J.; Vivekanandan, P. CpG dinucleotide frequencies reveal the role of host methylation capabilities in parvovirus evolution. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 13816–13824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alinejad-Rokny, H.; Anwar, F.; Waters, S.A.; Davenport, M.P.; Ebrahimi, D. Source of CpG depletion in the HIV-1 genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 3205–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojobori, T.; Li, W.H.; Graur, D. Patterns of nucleotide substitution in pseudogenes and functional genes. J. Mol. Evol. 1982, 18, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochman, H. Neutral mutations and neutral substitutions in bacterial genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003, 20, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, W.C.; Ma, L.; Becher, H.; Garcia, S.; Kovarikova, A.; Leitch, I.J.; Leitch, A.R.; Kovarik, A. Astonishing 35S rDNA diversity in the gymnosperm species Cycas revoluta Thunb. Chromosoma 2016, 125, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, M. Neighboring base effects on substitution rates in pseudogenes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1986, 3, 322–329. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, I.; Bensasson, D.; Nichols, R.A. Transition-transversion bias is not universal: A counter example from grasshopper pseudogenes. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchene, S.; Ho, S.Y.; Holmes, E.C. Declining transition/transversion ratios through time reveal limitations to the accuracy of nucleotide substitution models. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afgan, E.; Baker, D.; Batut, B.; van den Beek, M.; Bouvier, D.; Cech, M.; Chilton, J.; Clements, D.; Coraor, N.; Grüning, B.A.; et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2018 update. Nucl. Acids Res. 2018, 46, W537–W544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozas, J.; Rozas, R. DnaSP version 2.0: A novel software package for extensive molecular population genetics analysis. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1997, 13, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera–A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyte, J.; Doolittle, R.F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982, 157, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouy, M.; Guindon, S.; Gascuel, O. SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BoxPlotR: A Web-Tool for Generation of Box Plots. Available online: http://shiny.chemgrid.org/boxplotr/ (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Tang, X.; Wu, C.; Li, X.; Song, Y.; Yao, X.; Wu, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Qian, Z.; et al. On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, M.; Gascuel, O. Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: A fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Syst. Biol. 2006, 55, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Gojobori, T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1986, 3, 418–426. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, S. Why are RNA virus mutation rates so damn high? PLoS Biol. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachetti, M.; Marini, B.; Benedetti, F.; Giudici, F.; Mauro, E.; Storici, P.; Masciovecchio, C.; Angeletti, S.; Ciccozzi, M.; Gallo, R.C.; et al. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 mutation hot spots include a novel RNA-dependent-RNA polymerase variant. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minskaia, E.; Hertzig, T.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Campanacci, V.; Cambillau, C.; Canard, B.; Ziebuhr, J. Discovery of an RNA virus 3′->5′ exoribonuclease that is critically involved in coronavirus RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 5108–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethna, P.B.; Hofmann, M.A.; Brian, D.A. Minus-strand copies of replicating coronavirus mRNAs contain antileaders. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, H.; Wu, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.P.; Boerwinkle, E.; Fu, Y.X. Moderate mutation rate in the SARS coronavirus genome and its implications. BMC Evol. Biol. 2004, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.A.; Lawrence, M.S.; Klimczak, L.J.; Grimm, S.A.; Fargo, D.; Stojanov, P.; Kiezun, A.; Kryukov, G.V.; Carter, S.L.; Saksena, G.; et al. An APOBEC cytidine deaminase mutagenesis pattern is widespread in human cancers. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opi, S.; Takeuchi, H.; Kao, S.; Khan, M.A.; Miyagi, E.; Goila-Gaur, R.; Iwatani, Y.; Levin, J.G.; Strebel, K. Monomeric APOBEC3G is catalytically active and has antiviral activity. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 4673–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, M.; Vivekanandan, P. Depletion of CpG Dinucleotides in papillomaviruses and polyomaviruses: A role for divergent evolutionary pressures. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinman, D.M.; Yamshchikov, G.; Ishigatsubo, Y. Contribution of CpG motifs to the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines. J. Immunol. 1997, 158, 3635–3639. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Rates of conservative and radical nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions in mammalian nuclear genes. J. Mol. Evol. 2000, 50, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cytosine Deamination and Evolution. Available online: https://designmatrix.wordpress.com/2009/02/22/cytosine-deamination-and-evolution/ (accessed on 9 January 2020).

| Region (1) | Size (nt) | Synonymous | Nonsynonymous | Ka/Ks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RaTG13 | CoV-2 | Dif. (2) | Pos. (3) | Ks (4) | Dif. (1) | PPos. (2) | Ka (5) | ||

| whole | 3810 | 3822 | 221 | 888.7 | 0.3021 | 40 | 2915.2 | 0.0138 | 0.0457 |

| RBD | 153 | 153 | 21 | 36.6 | 1.0830 | 19 | 116.4 | 0.1841 | 0.1690 |

| rest | 3657 | 3669 | 200 | 855.2 | 0.2803 | 21 | 2798.8 | 0.0075 | 0.0268 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matyášek, R.; Kovařík, A. Mutation Patterns of Human SARS-CoV-2 and Bat RaTG13 Coronavirus Genomes Are Strongly Biased Towards C>U Transitions, Indicating Rapid Evolution in Their Hosts. Genes 2020, 11, 761. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11070761

Matyášek R, Kovařík A. Mutation Patterns of Human SARS-CoV-2 and Bat RaTG13 Coronavirus Genomes Are Strongly Biased Towards C>U Transitions, Indicating Rapid Evolution in Their Hosts. Genes. 2020; 11(7):761. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11070761

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatyášek, Roman, and Aleš Kovařík. 2020. "Mutation Patterns of Human SARS-CoV-2 and Bat RaTG13 Coronavirus Genomes Are Strongly Biased Towards C>U Transitions, Indicating Rapid Evolution in Their Hosts" Genes 11, no. 7: 761. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11070761

APA StyleMatyášek, R., & Kovařík, A. (2020). Mutation Patterns of Human SARS-CoV-2 and Bat RaTG13 Coronavirus Genomes Are Strongly Biased Towards C>U Transitions, Indicating Rapid Evolution in Their Hosts. Genes, 11(7), 761. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11070761