Gene Regulation via the Combination of Transcription Factors in the INDETERMINATE DOMAIN and GRAS Families

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast One-Hybrid Assay

2.2. Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

2.3. Construction of Vectors for the Transient Assay

2.4. Transient Assay

3. Results

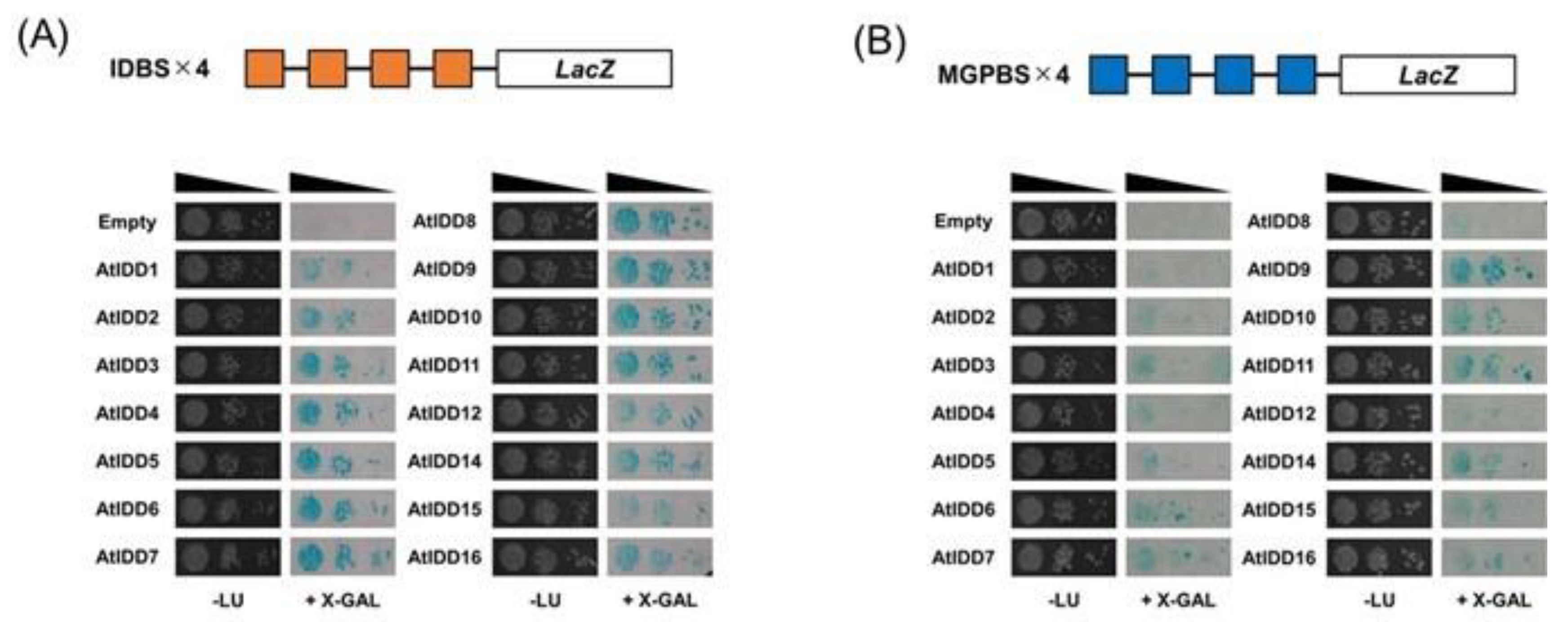

3.1. DNA Binding Properties of IDD Proteins

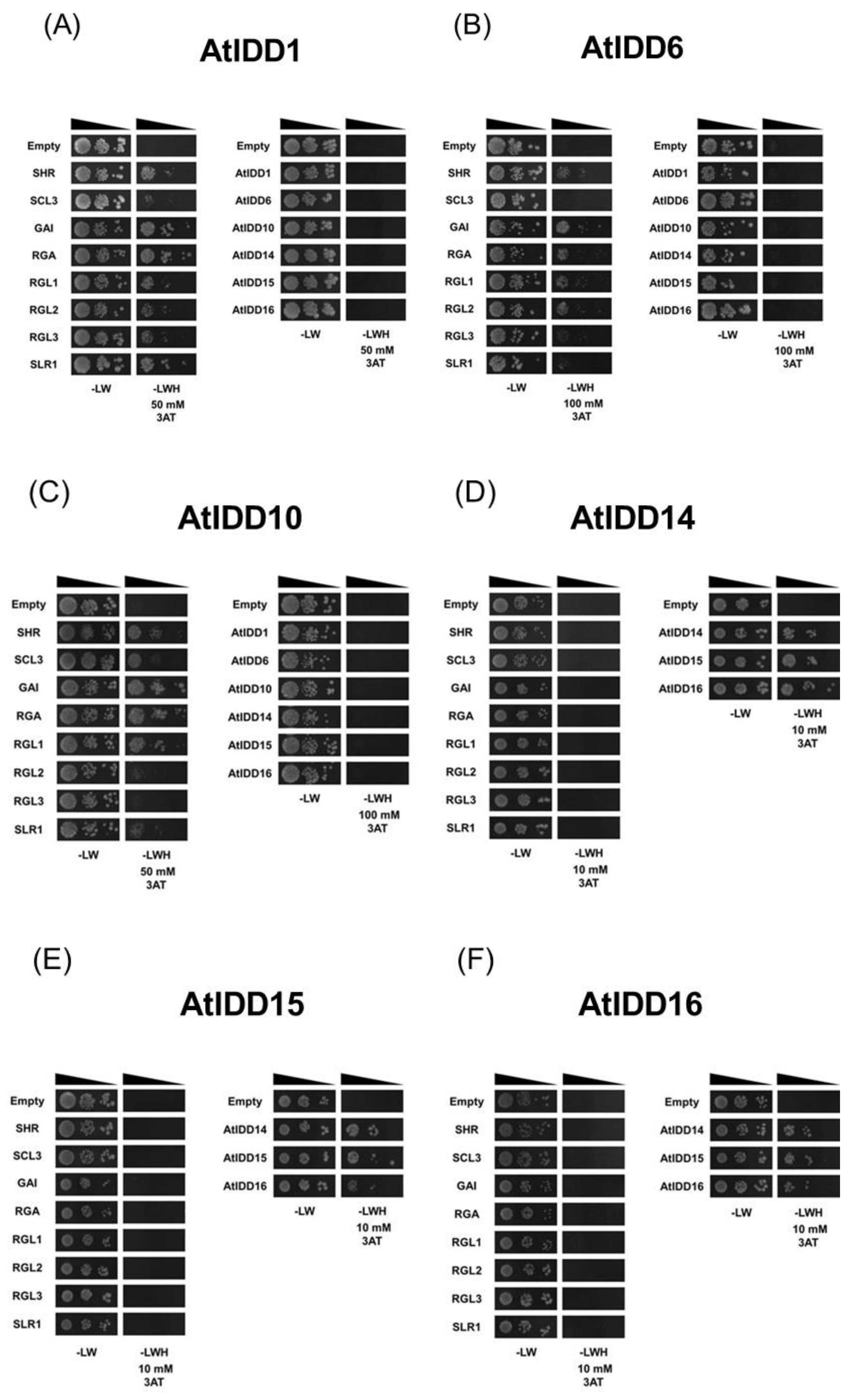

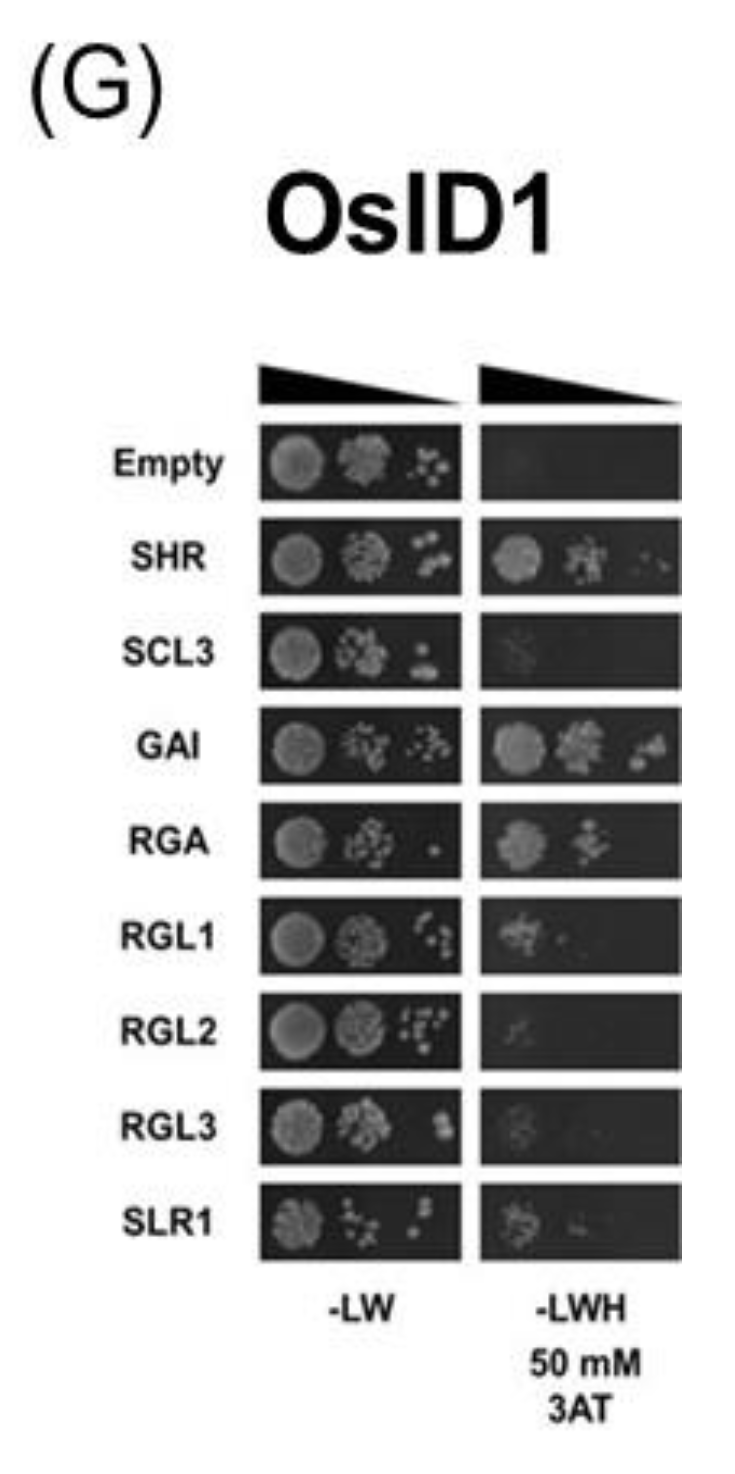

3.2. Protein–Protein Interaction of IDD Proteins

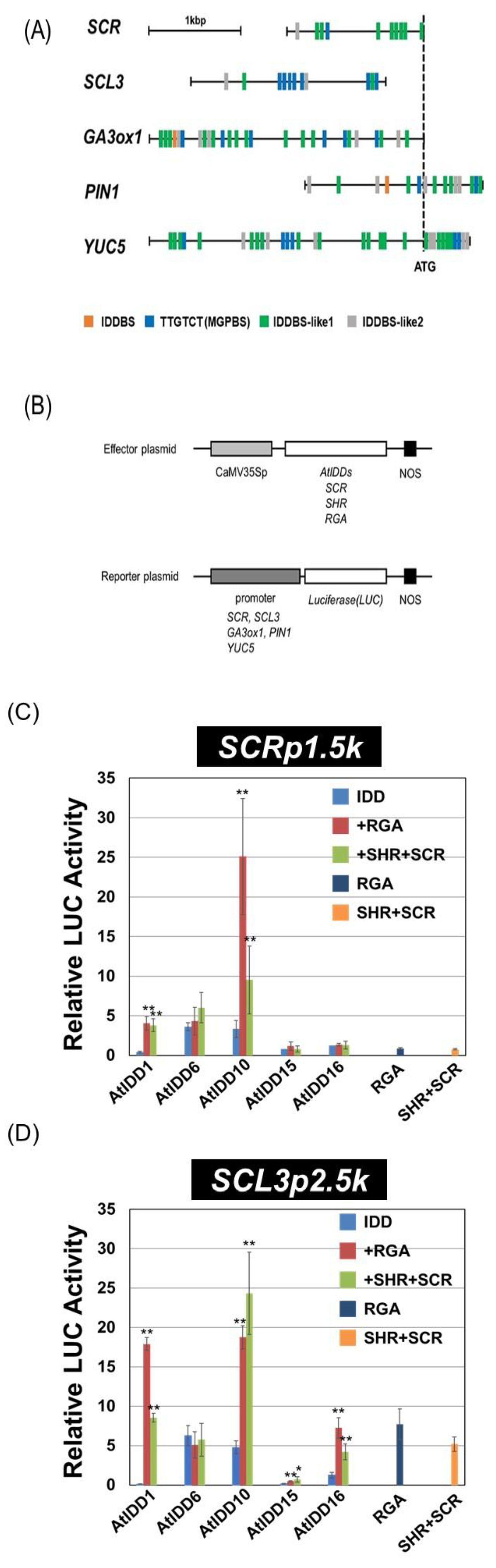

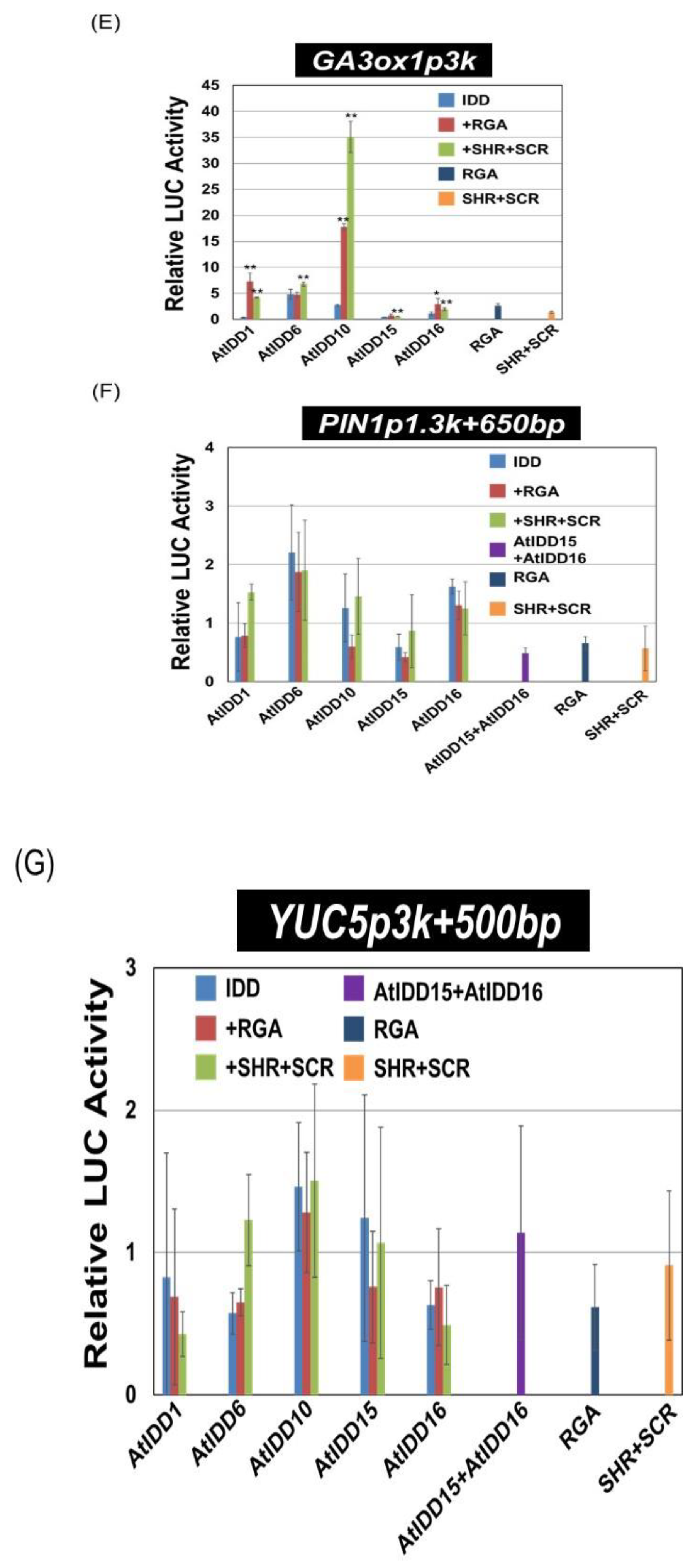

3.3. Transcriptional Activities of the Combination of AtIDD and GRAS Proteins

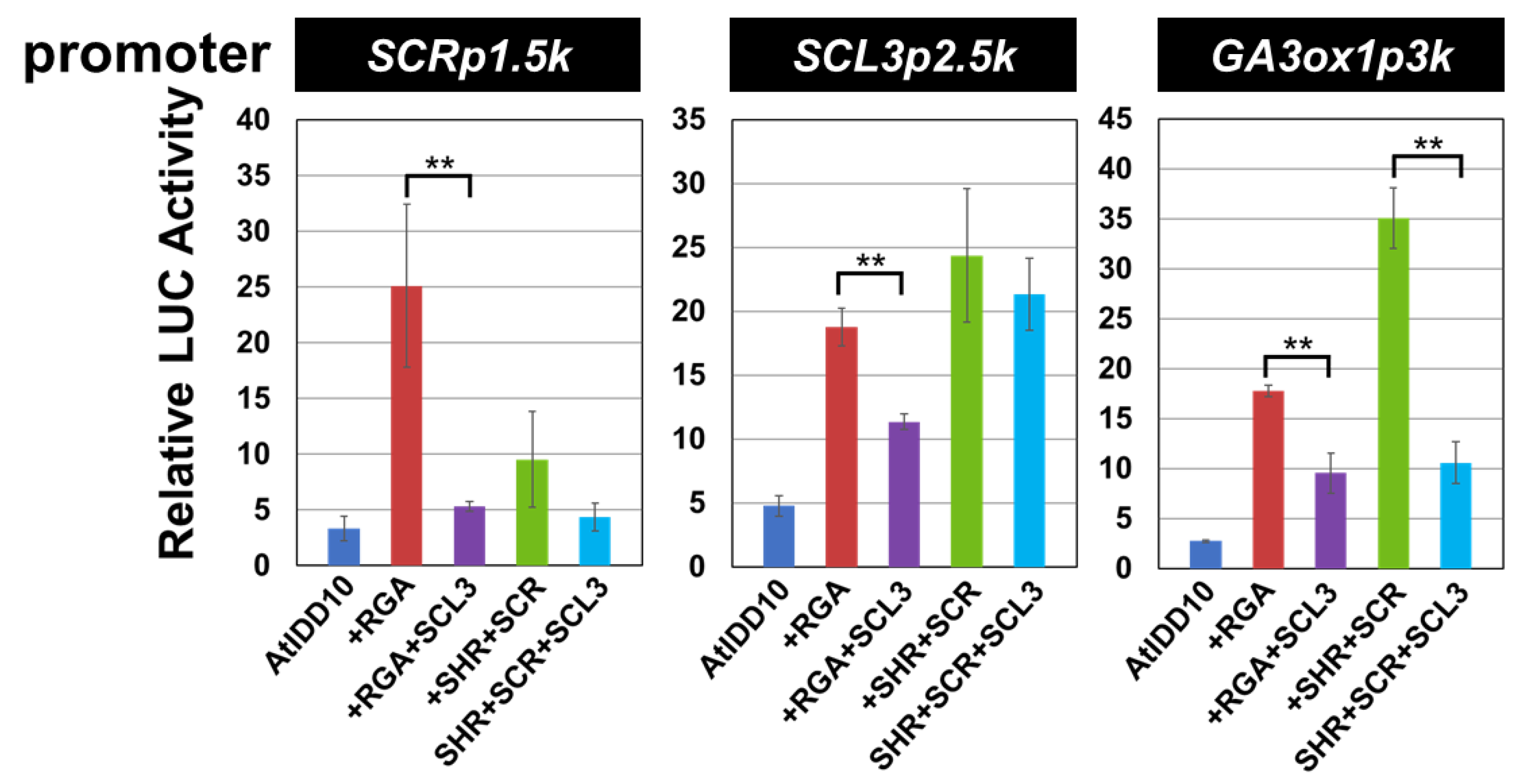

3.4. Effect of SCL3 on the Activity of the AtIDD10 and RGA Complex

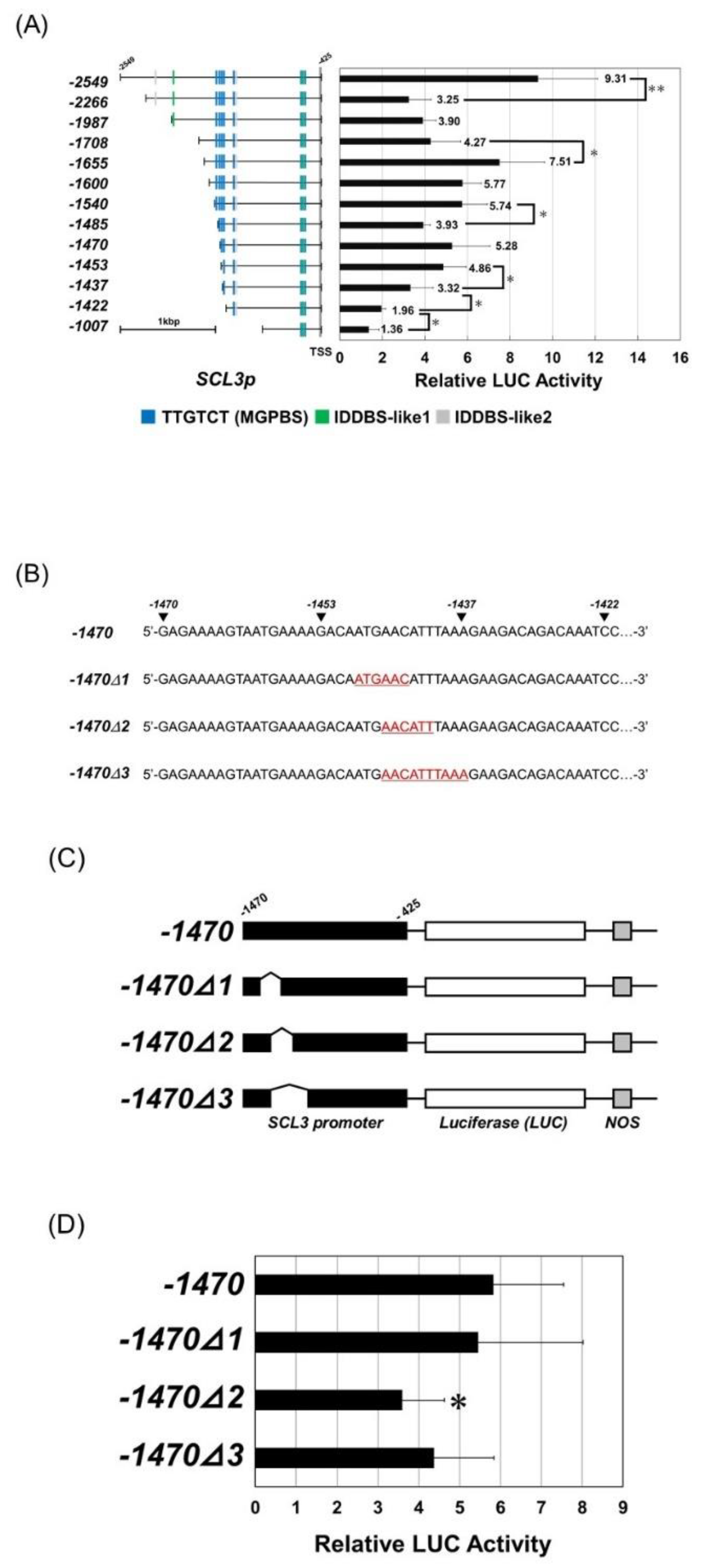

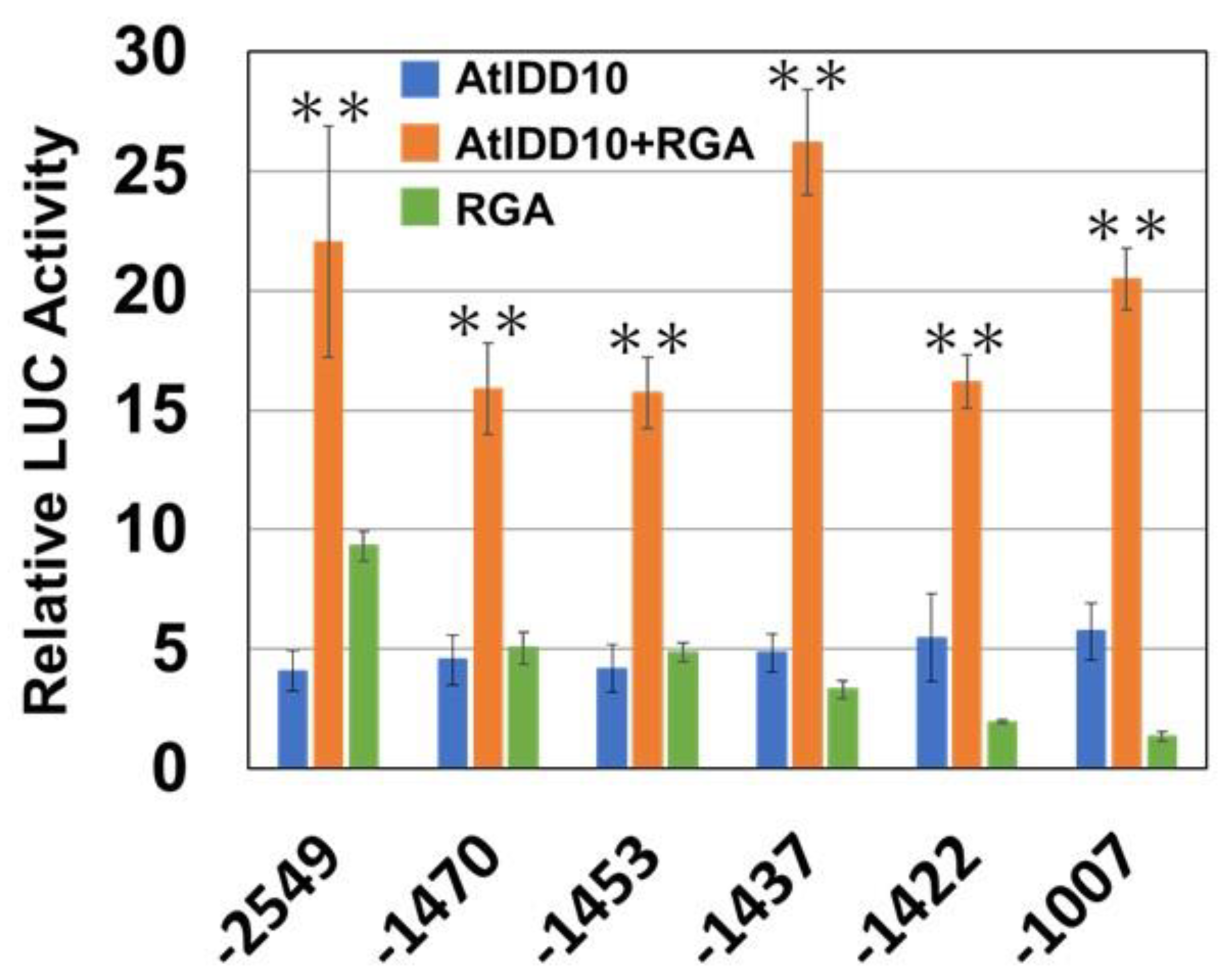

3.5. Binding Region of RGA on the SCL3 Promoter

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wray, G.A.; Hahn, M.W.; Abouheif, E.; Balhoff, J.P.; Pizer, M.; Rockman, M.V.; Romano, L.A. The Evolution of Transcriptional Regulation in Eukaryotes. Mol. Boil. Evol. 2003, 20, 1377–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riechmann, J.L.; Heard, J.; Martin, G.; Reuber, L.; Jiang, C.; Keddie, J.; Adam, L.; Pineda, O.; Ratcliffe, O.J.; Samaha, R.R.; et al. Arabidopsis Transcription Factors: Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis Among Eukaryotes. Science 2000, 290, 2105–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colasanti, J.; Tremblay, R.; Wong, A.Y.M.; Coneva, V.; Kozaki, A.; Mable, B.K. The maize INDETERMINATE1 flowering time regulator defines a highly conserved zinc finger protein family in higher plants. BMC Genom. 2006, 7, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasanti, J.; Yuan, Z.; Sundaresan, V. The indeterminate Gene Encodes a Zinc Finger Protein and Regulates a Leaf-Generated Signal Required for the Transition to Flowering in Maize. Cell 1998, 93, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, D.; Hassan, H.; Blilou, I.; Immink, R.G.; Heidstra, R.; Scheres, B. Arabidopsis JACKDAW and MAGPIE zinc finger proteins delimit asymmetric cell division and stabilize tissue boundaries by restricting SHORT-ROOT action. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 2196–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillo-Avendaño, E.; Ibáñez, S.; Sanz, O.; Barros, J.A.S.; Gude, I.; Perianez-Rodriguez, J.; Micol, J.L.; Del Pozo, J.C.; Moreno-Risueno, M.A.; Pérez-Pérez, J.M. Regulation of Hormonal Control, Cell Reprogramming, and Patterning during De Novo Root Organogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2017, 176, 1709–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Smet, W.; Cruz-Ramírez, A.; Castelijns, B.; De Jonge, W.; Mähönen, A.P.; Bouchet, B.P.; Perez, G.S.; Akhmanova, A.; Scheres, B.; et al. Arabidopsis BIRD Zinc Finger Proteins Jointly Stabilize Tissue Boundaries by Confining the Cell Fate Regulator SHORT-ROOT and Contributing to Fate Specification. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Hirano, K.; Sato, T.; Mitsuda, N.; Nomoto, M.; Maeo, K.; Koketsu, E.; Mitani, R.; Kawamura, M.; Ishiguro, S.; et al. DELLA protein functions as a transcriptional activator through the DNA binding of the indeterminate domain family proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7861–7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukazawa, J.; Teramura, H.; Murakoshi, S.; Nasuno, K.; Nishida, N.; Ito, T.; Yoshida, M.; Kamiya, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Takahashi, Y. DELLAs function as coactivators of GAI-ASSOCIATED FACTOR1 in regulation of gibberellin homeostasis and signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 2920–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentella, R.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Park, M.; Thomas, S.G.; Endo, A.; Murase, K.; Fleet, C.M.; Jikumaru, Y.; Nambara, E.; Kamiya, Y.; et al. Global Analysis of DELLA Direct Targets in Early Gibberellin Signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 3037–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-L.; Ogawa, M.; Fleet, C.M.; Zentella, R.; Hu, J.; Heo, J.-O.; Lim, J.; Kamiya, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Sun, T.-P. scarecrow-like 3 promotes gibberellin signaling by antagonizing master growth repressor DELLA in arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieu, I.; Ruiz-Rivero, O.; Fernandez-Garcia, N.; Griffiths, J.; Powers, S.J.; Gong, F.; Linhartova, T.; Eriksson, S.; Nilsson, O.; Thomas, S.G.; et al. The gibberellin biosynthetic genes AtGA20ox1 and AtGA20ox2 act, partially redundantly, to promote growth and development throughout the Arabidopsis life cycle. Plant J. 2007, 53, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feurtado, J.A.; Huang, D.; Wicki-Stordeur, L.; Hemstock, L.E.; Potentier, M.S.; Tsang, E.W.; Cutler, A.J. The Arabidopsis C2H2 zinc finger INDETERMINATE DOMAIN1/ENHYDROUS promotes the transition to germination by regulating light and hormonal signaling during seed maturation. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1772–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, P.J.; Kim, M.J.; Ryu, J.-Y.; Jeong, E.-Y.; Park, C.-M. Two splice variants of the IDD14 transcription factor competitively form nonfunctional heterodimers which may regulate starch metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, P.J.; Ryu, J.; Kang, S.K.; Park, C.-M. Modulation of sugar metabolism by an INDETERMINATE DOMAIN transcription factor contributes to photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010, 65, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Völz, R.; Kim, S.-K.; Mi, J.; Rawat, A.A.; Veluchamy, A.; Mariappan, K.G.; Rayapuram, N.; Daviere, J.-M.; Achard, P.; Blilou, I.; et al. INDETERMINATE-DOMAIN 4 (IDD4) coordinates immune responses with plant-growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.T.; Sakaguchi, K.; Kiyose, S.-I.; Taira, K.; Kato, T.; Nakamura, M.; Tasaka, M. A C2H2-type zinc finger protein, SGR5, is involved in early events of gravitropism in Arabidopsis inflorescence stems. Plant J. 2006, 47, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Zhao, J.; Jing, Y.; Fan, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Xin, W.; Hu, Y. The Arabidopsis IDD14, IDD15, and IDD16 Cooperatively Regulate Lateral Organ Morphogenesis and Gravitropism by Promoting Auxin Biosynthesis and Transport. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, S.L.; Lee, S.; Je, B.I.; Piao, H.L.; Park, S.H.; Kim, C.M.; Ryu, C.-H.; Park, S.H.; Xuan, Y.-H.; et al. RiceIndeterminate 1 (OsId1) is necessary for the expression of Ehd1 (Early heading date 1) regardless of photoperiod. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008, 56, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; You, C.; Li, C.; Long, T.; Chen, G.; Byrne, M.E.; Zhang, Q. RID1, encoding a Cys2/His2-type zinc finger transcription factor, acts as a master switch from vegetative to floral development in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 12915–12920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, K.; Yamanouchi, U.; Wang, Z.-X.; Minobe, Y.; Izawa, T.; Yano, M. Ehd2, a Rice Ortholog of the Maize INDETERMINATE1 Gene, Promotes Flowering by Up-Regulating Ehd11. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Y.H.; Priatama, R.; Huang, J.; Je, B.I.; Liu, J.M.; Park, S.J.; Piao, H.; Son, D.Y.; Lee, J.J.; Park, S.H.; et al. Indeterminate domain 10 regulates ammonium-mediated gene expression in rice roots. New Phytol. 2012, 197, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Yoshida, H.; Yano, K.; Kinoshita, S.; Kawai, K.; Koketsu, E.; Hattori, M.; Takehara, S.; Huang, J.; Hirano, K.; et al. OsIDD2, a zinc finger and INDETERMINATE DOMAIN protein, regulates secondary cell wall formation. J. Integr. Plant Boil. 2017, 60, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.; Wan, P.; Sun, S.; Li, J.; Chen, M. Genome-Wide Analysis of the GRAS Gene Family in Rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Boil. 2004, 54, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverstone, A.L.; Ciampaglio, C.N.; Sun, T.-P. The Arabidopsis RGA Gene Encodes a Transcriptional Regulator Repressing the Gibberellin Signal Transduction Pathway. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Richards, D.E.; Hartley, N.M.; Murphy, G.P.; Devos, K.M.; Flintham, J.E.; Beales, J.; Fish, L.J.; Worland, A.J.; Pelica, F.; et al. ‘Green revolution’ genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature 1999, 400, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pysh, L.D.; Wysocka-Diller, J.W.; Camilleri, C.; Bouchez, D.; Benfey, P.N. The GRAS gene family in Arabidopsis: Sequence characterization and basic expression analysis of the SCARECROW-LIKE genes. Plant J. 1999, 18, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locascio, A.; Blázquez, M.A.; Alabadí, D. Genomic Analysis of DELLA Protein Activity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucas, M.; Davière, J.-M.; Rodríguez-Falcón, M.; Pontin, M.; Pedraz, J.M.I.; Lorrain, S.; Fankhauser, C.; Blázquez, M.A.; Titarenko, E.; Prat, S. A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 2008, 451, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Bai, M.-Y.; Arenhart, R.A.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.-Y. Cell elongation is regulated through a central circuit of interacting transcription factors in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl. Elife 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Ji, Y.; He, W.; Jiang, Z.; Li, M.; Guo, H. Coordinated regulation of apical hook development by gibberellins and ethylene in etiolated Arabidopsis seedlings. Cell Res. 2012, 22, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Lee, L.Y.C.; Xia, K.; Yan, Y.; Yu, H. DELLAs Modulate Jasmonate Signaling via Competitive Binding to JAZs. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozaki, A.; Hake, S.; Colasanti, J. The maize ID1 flowering time regulator is a zinc finger protein with novel DNA binding properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeo, K.; Tokuda, T.; Ayame, A.; Mitsui, N.; Kawai, T.; Tsukagoshi, H.; Ishiguro, S.; Nakamura, K. An AP2-type transcription factor, WRINKLED1, ofArabidopsis thalianabinds to the AW-box sequence conserved among proximal upstream regions of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Boil. 2009, 60, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, H.; Kaimi, R.; Colasanti, J.; Kozaki, A. Activity of transcription factor JACKDAW is essential for SHR/SCR-dependent activation of SCARECROW and MAGPIE and is modulated by reciprocal interactions with MAGPIE, SCARECROW and SHORT ROOT. Plant Mol. Boil. 2011, 77, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Ryu, J.Y.; Baek, K.; Park, C.-M. High temperature attenuates the gravitropism of inflorescence stems by inducingSHOOT GRAVITROPISM 5alternative splicing inArabidopsis. New Phytol. 2015, 209, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidstra, R.; Welch, D.; Scheres, B. Mosaic analyses using marked activation and deletion clones dissect Arabidopsis SCARECROW action in asymmetric cell division. Genome Res. 2004, 18, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Miura, S.; Kozaki, A. INDETERMINATE DOMAIN PROTEIN binding sequences in the 5′-untranslated region and promoter of the SCARECROW gene play crucial and distinct roles in regulating SCARECROW expression in roots and leaves. Plant Mol. Boil. 2017, 16, 735–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.O.; Chang, K.S.; Kim, I.A.; Lee, M.H.; Lee, S.A.; Song, S.K.; Lee, M.M.; Lim, J. funneling of gibberellin signaling by the GRAS transcription regulator scarecrow-like 3 in the arabidopsis root. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2166–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Mitchum, M.G.; Barnaby, N.; Ayele, B.T.; Ogawa, M.; Nam, E.; Lai, W.-C.; Hanada, A.; Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R.; et al. Potential Sites of Bioactive Gibberellin Production during Reproductive Growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchum, M.G.; Yamaguchi, S.; Hanada, A.; Kuwahara, A.; Yoshioka, Y.; Kato, T.; Tabata, S.; Kamiya, Y.; Sun, T.-P. Distinct and overlapping roles of two gibberellin 3-oxidases in Arabidopsis development. Plant J. Cell Mol. Boil. 2006, 45, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkova, E.; Michniewicz, M.; Sauer, M.; Teichmann, T.; Seifertová, D.; Jürgens, G.; Friml, J. Local, Efflux-Dependent Auxin Gradients as a Common Module for Plant Organ Formation. Cell 2003, 115, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieten, A.; Vanneste, S.; Wiśniewska, J.; Benkova, E.; Benjamins, R.; Beeckman, T.; Luschnig, C.; Friml, J. Functional redundancy of PIN proteins is accompanied by auxin-dependent cross-regulation of PIN expression. Development 2005, 132, 4521–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Dai, X.; De-Paoli, H.; Cheng, Y.; Takebayashi, Y.; Kasahara, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Zhao, Y. Auxin overproduction in shoots cannot rescue auxin deficiencies in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, M.; Cheng, S.; Zhao, B.; Xuan, Y.; Shao, M. The Indeterminate Domain Protein ROC1 Regulates Chilling Tolerance via Activation of DREB1B/CBF1 in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakoshima, T. Structural basis of the specific interactions of GRAS family proteins. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, M.P.; Vernoux, T.; Busch, W.; Cui, H.; Wang, J.Y.; Blilou, I.; Hassan, H.; Nakajima, K.; Matsumoto, N.; Lohmann, J.U.; et al. Whole-Genome Analysis of the SHORT-ROOT Developmental Pathway in Arabidopsis. PLoS Boil. 2006, 4, e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Levesque, M.P.; Vernoux, T.; Jung, J.W.; Paquette, A.J.; Gallagher, K.L.; Wang, J.Y.; Blilou, I.; Scheres, B.; Benfey, P.N. An Evolutionarily Conserved Mechanism Delimiting SHR Movement Defines a Single Layer of Endodermis in Plants. Science 2007, 316, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Harberd, N.P. Auxin promotes Arabidopsis root growth by modulating gibberellin response. Nature 2003, 421, 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, S.U.; Federici, F.; Casimiro, I.; Beemster, G.T.; Bhalerao, R.P.; Swarup, R.; Doerner, P.; Haseloff, J.; Bennett, M.J. Gibberellin Signaling in the Endodermis Controls Arabidopsis Root Meristem Size. Curr. Boil. 2009, 19, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Kamiya, Y.; Sun, T.-P. Distinct cell-specific expression patterns of early and late gibberellin biosynthetic genes during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant J. 2001, 28, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achard, P.; Chen, D.; Steele, A.D.; Lindquist, S.; Guarente, L. Integration of Plant Responses to Environmentally Activated Phytohormonal Signals. Science 2006, 311, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, S.; Kim, J.; Muñoz, A.; Heckmann, A.B.; Downie, J.A.; Oldroyd, G.E.D. GRAS Proteins Form a DNA Binding Complex to Induce Gene Expression during Nodulation Signaling in Medicago truncatula[W]. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Ma, N.; Pei, H.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Gao, J. A DELLA gene, RhGAI1, is a direct target of EIN3 and mediates ethylene-regulated rose petal cell expansion via repressing the expression of RhCesA2. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 5075–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y. Crystal Structure of the GRAS Domain of SCARECROW-LIKE7 in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaya, E.; Nakajima, N.; Okada, K. Non-sequence-specific DNA Binding by the FILAMENTOUS FLOWER Protein fromArabidopsis thalianaIs Reduced by EDTA. J. Boil. Chem. 2002, 277, 11957–11964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Q.; Hu, Y.; Hedden, P.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, D.-X. The Rice YABBY1 Gene Is Involved in the Feedback Regulation of Gibberellin Metabolism1. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Y.Y.; Mesnage, S.; Mylne, J.S.; Gendall, A.; Dean, C. Multiple Roles of Arabidopsis VRN1 in Vernalization and Flowering Time Control. Science 2002, 297, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aoyanagi, T.; Ikeya, S.; Kobayashi, A.; Kozaki, A. Gene Regulation via the Combination of Transcription Factors in the INDETERMINATE DOMAIN and GRAS Families. Genes 2020, 11, 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11060613

Aoyanagi T, Ikeya S, Kobayashi A, Kozaki A. Gene Regulation via the Combination of Transcription Factors in the INDETERMINATE DOMAIN and GRAS Families. Genes. 2020; 11(6):613. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11060613

Chicago/Turabian StyleAoyanagi, Takuya, Shun Ikeya, Atsushi Kobayashi, and Akiko Kozaki. 2020. "Gene Regulation via the Combination of Transcription Factors in the INDETERMINATE DOMAIN and GRAS Families" Genes 11, no. 6: 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11060613

APA StyleAoyanagi, T., Ikeya, S., Kobayashi, A., & Kozaki, A. (2020). Gene Regulation via the Combination of Transcription Factors in the INDETERMINATE DOMAIN and GRAS Families. Genes, 11(6), 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11060613