Insights into Xylan Degradation and Haloalkaline Adaptation through Whole-Genome Analysis of Alkalitalea saponilacus, an Anaerobic Haloalkaliphilic Bacterium Capable of Secreting Novel Halostable Xylanase

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Concentration and Characterization of the Xylanase

2.2. Genome Sequencing, Annotation and Analysis Pipelines

3. Results and Discussion

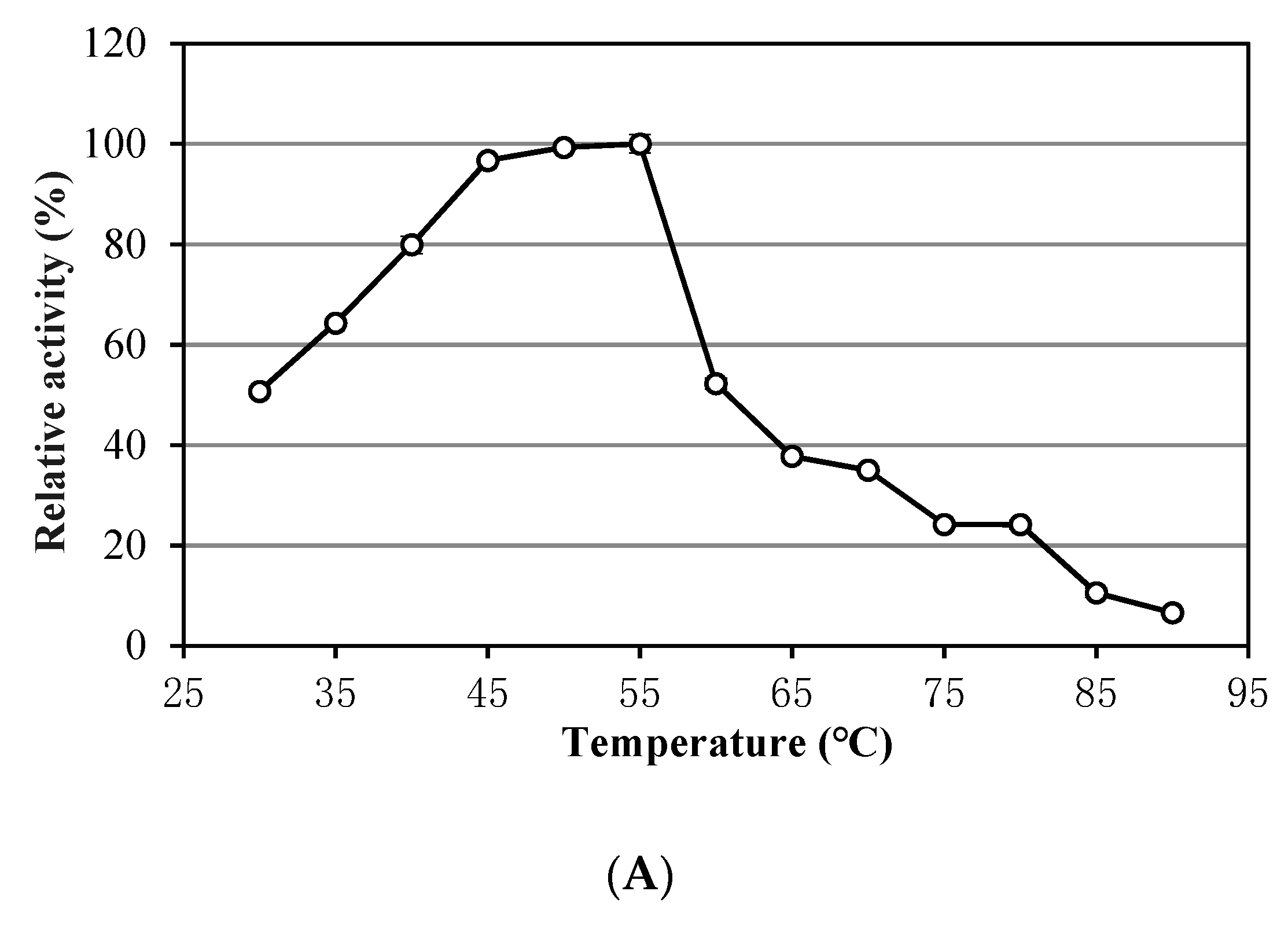

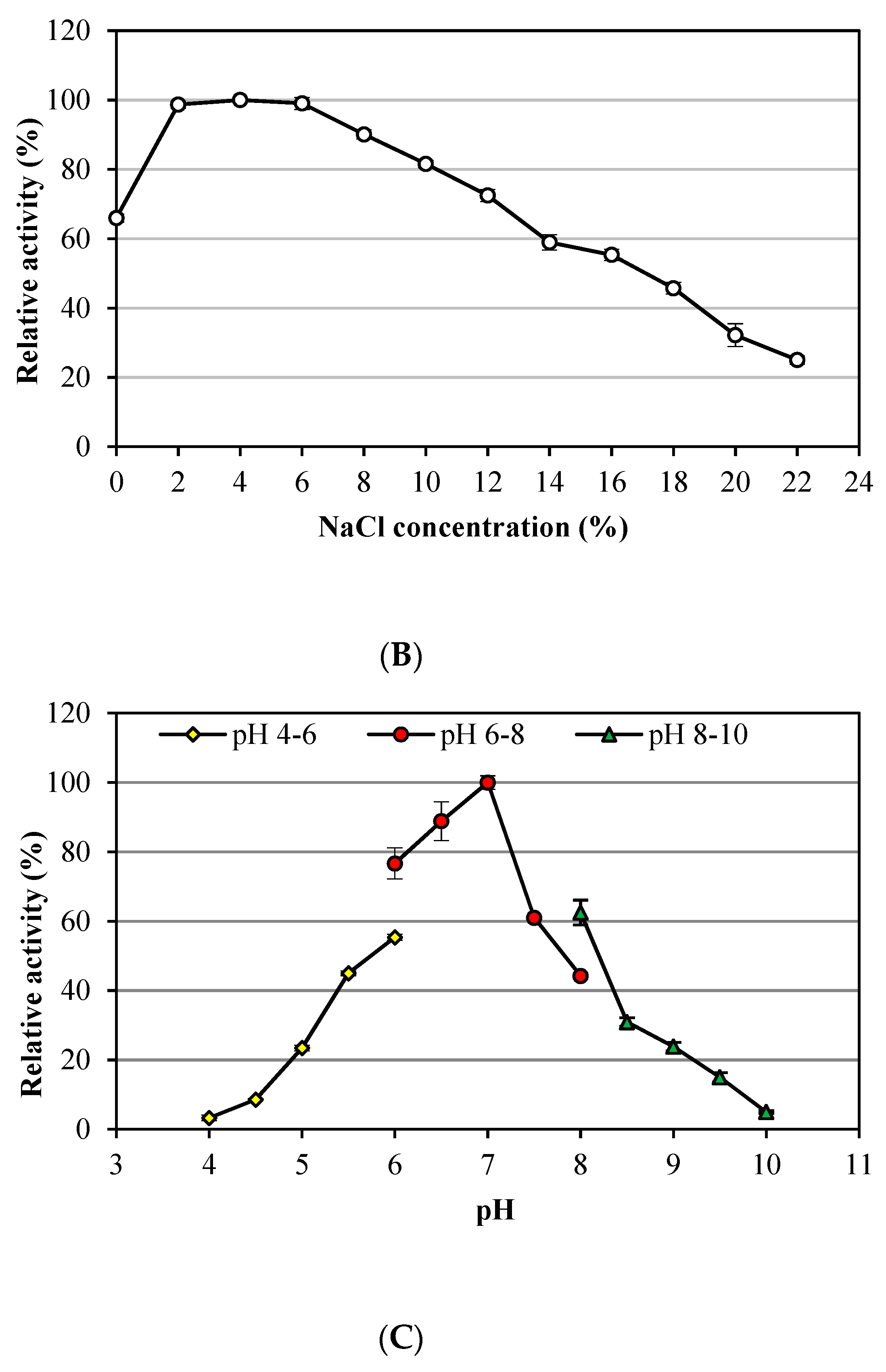

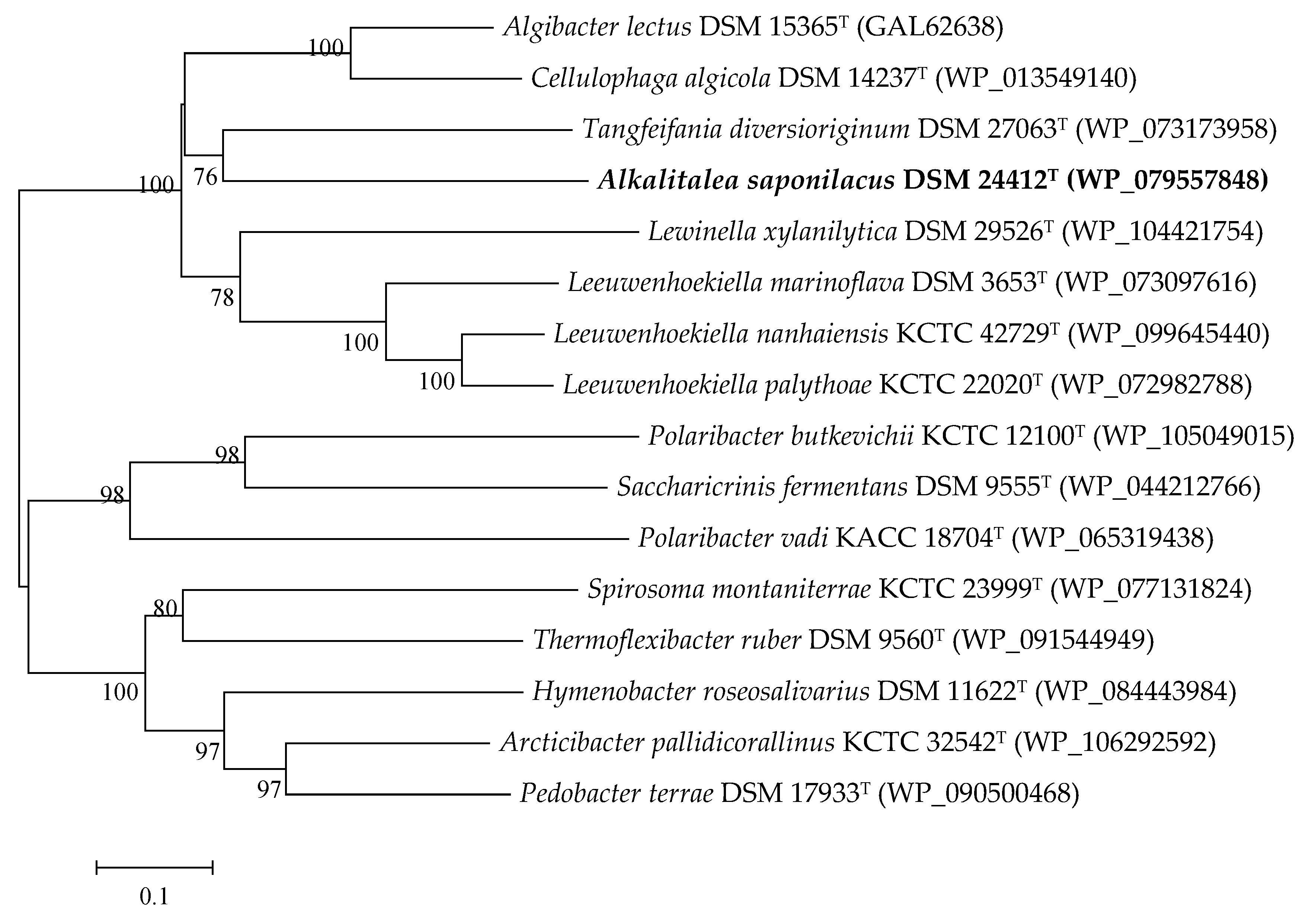

3.1. Characteristics of Alkalitalea saponilacus Xylanase

3.2. Genome Features of Alkalitalea saponilacus

3.3. The Identified Xylan-Degrading Related Enzymes in Alkalitalea saponilacus

3.4. The Predicted Xylan Degradation Pathways in Alkalitalea saponilacus

3.5. The Genes Involved in Adaptation to Saline-Alkaline Conditions in Alkalitalea saponilacus

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, B.; Yan, Y.; Chen, S. How could haloalkaliphilic microorganisms contribute to biotechnology? Can. J. Microbiol. 2014, 60, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Jun, L. Biodiversity of culture-dependent haloalkaliphilic microorganisms. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 2017, 57, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar]

- De Graaff, M.; Bijmans, M.F.; Abbas, B.; Euverink, G.J.; Muyzer, G.; Janssen, A.J. Biological treatment of refinery spent caustics under halo-alkaline conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 7257–7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.E.; Grant, W.D.; Duckworth, A.W.; Owenson, G.G. Microbial diversity of soda lakes. Extremophiles 1998, 2, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, H.B.; Gohel, S.D.; Singh, S.P. Phylogeny, novel bacterial lineage and enzymatic potential of haloalkaliphilic bacteria from the saline coastal desert of Little Rann of Kutch, Gujarat, India. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohel, S.D.; Sharma, A.K.; Dangar, K.G.; Thakrar, F.J.; Singh, S.P. Biology and applications of halophilic and haloalkaliphilic actinobacteria. In Extremophiles from Biology to Biotechnology; Durvasula, R.V., Subba Rao, D.V., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Chen, S. Alkalitalea saponilacus gen. nov. sp. nov. an obligately anaerobic, alkaliphilic, xylanolytic bacterium from a meromictic soda lake. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2012, 62, 2618–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Luo, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Cai, Y.; Wen, B.; Cui, Z.; Wang, X. Improving the methane yield of maize straw: Focus on the effects of pretreatment with fungi and their secreted enzymes combined with sodium hydroxide. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, C.S.; Alexander, D.H.; Marks, P.; Klammer, A.A.; Drake, J.; Heiner, C.; Clum, A.; Copeland, A.; Huddleston, J.; Eichler, E.E.; et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, S.; Schatz, M.C.; Walenz, B.P.; Martin, J.; Howard, J.T.; Ganapathy, G.; Wang, Z.; Rasko, D.A.; McCombie, W.R.; Jarvis, E.D.; et al. Hybrid error correction and de novo assembly of single-molecule sequencing reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, E.W.; Sutton, G.G.; Delcher, A.L.; Dew, I.M.; Fasulo, D.P.; Flanigan, M.J.; Kravitz, S.A.; Mobarry, C.M.; Reinert, K.H.; Remington, K.A.; et al. A whole-genome assembly of Drosophila. Science 2000, 287, 2196–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.J.; Carneiro, M.O.; Schatz, M.C. The advantages of SMRT sequencing. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, B.J.; Abeel, T.; Shea, T.; Priest, M.; Abouelliel, A.; Sakthikumar, S.; Cuomo, C.A.; Zeng, Q.; Wortman, J.; Young, S.K.; et al. Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delcher, A.L.; Bratke, K.A.; Powers, E.C.; Salzberg, S.L. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatusova, T.; DiCuccio, M.; Badretdin, A.; Chetvernin, V.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Zaslavsky, L.; Lomsadze, A.; Pruitt, K.D.; Borodovsky, M.; Ostell, J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 6614–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, V.M.; Mavromatis, K.; Ivanova, N.N.; Chen, I.M; Chu, K.; Kyrpides, N.C. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2271–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Stamatis, D.; Bertsch, J.; Ovchinnikova, G.; Verezemska, O.; Isbandi, M.; Thomas, A.D.; Ali, R.; Sharma, K.; Kyrpides, N.C; et al. Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v.6: data updates and feature enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D446–D456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, R.; Foerster, H.; Fulcher, C.A.; Kaipa, P.; Krummenacker, M.; Latendresse, M.; Paley, S.; Rhee, S.Y.; Shearer, A.G.; Tissier, C.; Walk, T.C.; Zhang, P.; Karp, P.D. The MetaCyc Database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of Pathway/Genome Databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, D623–D631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratanakhanokchai, K.; Kyu, K.L.; Tanticharoen, M. Purification and properties of a xylan-binding endoxylanase from alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. strain K-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 694–697. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, M.; Saleem, M.; Jamil, S. Production of xylanase on natural substrates Bacillus subtilis. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2013, 2, 211–213. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, F.L.; Andrade, C.C.P.; Santana, M.H.A. A review of xylanase production by the fermentation of xylan. classification, characterization and applications. In Sustainable Degradation of Lignocellulosic Biomass-Techniques, Applications and Commercialization; Chandel, A.K., da Silva, S.S., Eds.; INTECH: Chennai, India, 2013; pp. 251–275. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, B.C. Purification and properties of an extracellular beta-xylosidase from newly isolated Fusarium proliferatum. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 90, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, O.L.; Villaseñor-Ortega, F. 14 Xylanases. In Advances in Agricultural and Food Biotechnology; Guevara-González, R.G., Torres-Pacheco, I., Eds.; Research Signpost: Kerala, India, 2006; pp. 305–322. [Google Scholar]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temudo, M.F.; Mato, T.; Kleerebezem, R.; van Loosdrecht, M.C. Xylose anaerobic conversion by open-mixed cultures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 82, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Liu, J.; Qi, Y.; Yang, K.; Xu, Y.; Feng, L. Synergistic hydrolysis of xylan using novel xylanases, β-xylosidases, and an α-L-arabinofuranosidase from Geobacillus thermodenitrificans NG80-2. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banciu, H.L.; Sorokin, D.Y. Adaptation in haloalkaliphiles and natronophilic bacteria. In Polyextremophiles: Life Under Multiple Forms of Stress; Seckbach, J., Oren, A., Stan-Lotter, H., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 121–178. [Google Scholar]

- Banciu, H.L.; Muntyan, M.S. Adaptive strategies in the double extremophilic prokaryotes inhabiting soda lakes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015, 25, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Mesbah, N.M.; Dalin, E.; Goodwin, L.; Nolan, M.; Pitluck, S.; Chertkov, O.; Brettin, T.S.; Han, J.; Larimer, F.W.; et al. Complete genome sequence of the anaerobic, halophilic alkalithermophile Natranaerobius thermophilus JW/NM-WN-LF. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 4023–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.F. Organic compatible solutes of halotolerant and halophilic microorganisms. Saline Syst. 2005, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aono, R.; Ito, M.; Machida, T. Contribution of the cell wall component teichuronopeptide to pH homeostasis and alkaliphily in the alkaliphile Bacillus lentus C-125. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6600–6606. [Google Scholar]

- Krulwich, T.A.; Sachs, G.; Padan, E. Molecular aspects of bacterial pH sensing and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slonczewski, J.L.; Fujisawa, M.; Dopson, M.; Krulwich, T.A. Cytoplasmic pH measurement and homeostasis in bacteria and archaea. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2009, 55, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kochegarov, A.A. Modulators of ion-transporting ATPases. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2001, 11, 825–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Locus Tag | Product Name | GH |

|---|---|---|

| CDL62_17705 | Endo-β-1,4-xylanase (XynA) | GH10 |

| CDL62_00085 | β-xylosidase | GH43 |

| CDL62_06240 | β-xylosidase | GH43 |

| CDL62_06275 | β-xylosidase | GH43 |

| CDL62_06380 | β-xylosidase | GH43 |

| CDL62_15875 | β-xylosidase | GH43 |

| CDL62_02285 | β-xylosidase | GH43 |

| CDL62_00095 | α-glucuronidase | GH67 |

| CDL62_00195 | α-L-arabinofuranosidase | GH43 |

| CDL62_00495 | α-L-arabinofuranosidase | GH43 |

| CDL62_12950 | α-L-arabinofuranosidase | GH43 |

| CDL62_00395 | α-L-arabinofuranosidase | GH51 |

| Product Name | Locus Tag |

|---|---|

| L-glutamine synthesis | |

| L-glutamine synthetase, GlnA | CDL62_11360 |

| Choline/glycine/proline betaine transporter (BCCT family) | |

| Choline/glycine/proline betaine transport protein | CDL62_17705 |

| Na+/solute symporter | |

| Na+/solute symporter (SSS family) | CDL62_09935 |

| Na+/solute symporter (SSS family) | CDL62_06475 |

| Na+/solute symporter (SSS family) | CDL62_14105 |

| Na+/solute symporter (SSS family) | CDL62_11075 |

| K+ transport systems, potassium uptake protein (Trk family) | |

| Trk system potassium uptake protein, TrkA | CDL62_03510 |

| Trk system potassium uptake protein, TrkH | CDL62_03515 |

| Trk system potassium uptake protein, TrkA | CDL62_03555 |

| Trk system potassium uptake protein, TrkH | CDL62_12070 |

| Na+/H+ antiporter (NhaC family) | |

| H+/Na+ antiporter (NhaC family) | CDL62_06020 |

| Multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter | |

| Multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter, MrpA subunit | CDL62_14320 |

| Multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter, MrpB subunit | CDL62_14325 |

| Multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter, MrpC subunit | CDL62_14330 |

| Multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter, MrpD subunit | CDL62_14335 |

| Multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter, MnhE subunit | CDL62_14340 |

| Multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter, MnhF subunit | CDL62_14345 |

| Multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter, MrpG subunit | CDL62_14350 |

| Monovalent Cation/H+ antiporter (CPA family) | |

| K+/H+ antiporter (CPA1 family) | CDL62_09425 |

| K+/H+ antiporter (CPA1 family) | CDL62_00125 |

| Na+/H+ antiporter (CPA2 family) | CDL62_00920 |

| Na+/H+ antiporter (CPA2 family) | CDL62_05390 |

| F0F1-ATP synthase | |

| ATP synthase F1 subcomplex gamma subunit, AtpG | CDL62_07555 |

| ATP synthase F1 subcomplex alpha subunit, AtpA | CDL62_07560 |

| ATP synthase F1 subcomplex delta subunit, AtpH | CDL62_07565 |

| ATP synthase F0 subcomplex B subunit, AtpF | CDL62_07570 |

| ATP synthase F0 subcomplex C subunit, AtpE | CDL62_07575 |

| ATP synthase F0 subcomplex A subunit, AtpB | CDL62_07580 |

| ATP synthase F1 subcomplex epsilon subunit, AtpC | CDL62_07660 |

| ATP synthase F1 subcomplex beta subunit, AtpD | CDL62_07665 |

| H+-transporting two-sector ATPase (V-type ATP synthase) | |

| V/A-type H+-transporting ATPase subunit E, AtpE | CDL62_11640 |

| V/A-type H+-transporting ATPase subunit A, AtpA | CDL62_11650 |

| V/A-type H+-transporting ATPase subunit B, AtpB | CDL62_11655 |

| V/A-type H+-transporting ATPase subunit D, AtpD | CDL62_11660 |

| V/A-type H+-transporting ATPase subunit I, AtpI | CDL62_11665 |

| V/A-type H+-transporting ATPase subunit K, AtpK | CDL62_11670 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, Z.; Holtzapple, M.; Yan, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, B. Insights into Xylan Degradation and Haloalkaline Adaptation through Whole-Genome Analysis of Alkalitalea saponilacus, an Anaerobic Haloalkaliphilic Bacterium Capable of Secreting Novel Halostable Xylanase. Genes 2019, 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10010001

Liao Z, Holtzapple M, Yan Y, Wang H, Li J, Zhao B. Insights into Xylan Degradation and Haloalkaline Adaptation through Whole-Genome Analysis of Alkalitalea saponilacus, an Anaerobic Haloalkaliphilic Bacterium Capable of Secreting Novel Halostable Xylanase. Genes. 2019; 10(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Ziya, Mark Holtzapple, Yanchun Yan, Haisheng Wang, Jun Li, and Baisuo Zhao. 2019. "Insights into Xylan Degradation and Haloalkaline Adaptation through Whole-Genome Analysis of Alkalitalea saponilacus, an Anaerobic Haloalkaliphilic Bacterium Capable of Secreting Novel Halostable Xylanase" Genes 10, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10010001

APA StyleLiao, Z., Holtzapple, M., Yan, Y., Wang, H., Li, J., & Zhao, B. (2019). Insights into Xylan Degradation and Haloalkaline Adaptation through Whole-Genome Analysis of Alkalitalea saponilacus, an Anaerobic Haloalkaliphilic Bacterium Capable of Secreting Novel Halostable Xylanase. Genes, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10010001