Abstract

Bladder cancer (BC) is the tenth most frequent cancer worldwide and is associated with high mortality when diagnosed in its most aggressive form, which is not reverted by the current treatment options. Thus, the development of new therapeutic strategies, either alternative or complementary to the current ones, is of major importance. The disruption of normal epigenetic mechanisms, namely, DNA methylation, is a known early event in cancer development. Consequently, DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors constitute a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of BC. Although these inhibitors, mainly nucleoside analogues such as 5-azacytidine (5-aza) and decitabine (DAC), cause re-expression of tumor suppressor genes, inhibition of tumor cell growth, and increased apoptosis in BC experimental models and clinical trials, they also show important drawbacks that prevent their use as a valuable option for the treatment of BC. However, their combination with chemotherapy and/or immune-checkpoint inhibitors could aid in their implementation in the clinical practice. Here, we provide a comprehensive review of the studies exploring the effects of DNA methylation inhibition using DNMTs inhibitors in BC, from in vitro and in vivo studies to clinical trials.

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is estimated to be the tenth most frequent cancer worldwide, being more common in men, in which it is the sixth most frequent cancer and the ninth cause of death due to cancer [1]. At diagnosis, approximately 75% of patients display a non-muscle-invasive BC (NMIBC), whereas 25% are diagnosed with muscle-invasive BC (MIBC) [2]. These differences have important implications regarding the treatment and clinical outcome [3]. NMIBC comprises Ta, T1, and carcinoma in situ (CIS), which do not reach the bladder muscle layer and show relatively good outcomes [4], being treated by transurethral resection (TUR) [3]. Depending on different clinicopathological features, such as number of implants, size, and patient’s age, NMBICs are classified as high or low risk. High risk tumor management includes a regimen of local instillation, mainly of Bacillus Calmette Guérin (BCG), after TUR to prevent recurrences and progression. BCG instillations promote local acute inflammation responses and represent the first approved immunotherapy for human cancers [5]. Recurrence is extremely frequent in NMIBC (up to 70%), and, in a proportion of cases, tumors progress to MIBC (stage T2 or higher) [4,6]. This represents a clinical problem demanding systematic follow-up of patients, frequently requiring cystoscopy, with a serious impact on the patient’s quality of life and generating important costs to health systems [7]. The management of MIBC often requires radical cystectomy and, depending on the clinicopathological characteristics of the neoplasm, platin-based chemotherapy schemes in neoadjuvant or adjuvant settings can be administered [3]. MIBC recurrence and progression are also frequent, with survival at metastatic stage below 5% [6]. In addition to this poor outcome, a percentage of MIBC patients cannot be treated using standard protocols due to comorbidities or other health problems, regularly related to old age at diagnosis. Currently, patients that are considered to be unfit for such protocols have few therapeutic options. The development of immune checkpoint blockade (ICI) with antibodies inhibiting programmed death 1 (PD-1), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) allowed for a substantial improvement in patient survival with good and sustained responses [8]. However, the percentage of patients showing clinical response is still rather limited [9]. Hence, a full understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying the development of BC would not only provide novel biomarkers for early detection but also as candidate therapeutic targets, improving patient survival. To gain better knowledge of BC molecular features, different international initiatives and multiple groups generated large amounts of data including different genomic analyses [10,11]. Such studies revealed the existence of different molecular subtypes and suggested the possibility for designing appropriate subtype-specific therapeutic approaches [12].

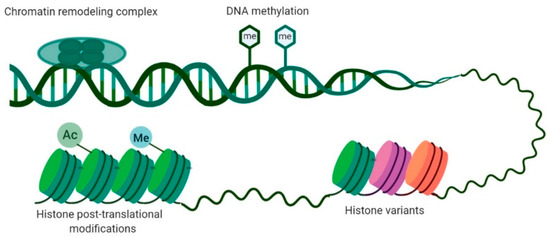

One of the most prevalent characteristics of BC is the presence of alterations in the cancer cell epigenetic machinery. The genetic and epigenetic landscapes allow for a cell to acquire an identity associated with a specific tissue, establishing proper organismal physiology [13], and their disruption represents the basis of multiple disorders [13]. Epigenetics comprises the study of heritable alterations that modify gene expression patterns without changing their DNA sequence [13,14,15]. DNA methylation, histone variants, chromatin remodeling, and histone post-translation modifications are the main epigenetic mechanisms with an impact on gene expression (Figure 1) [16]. Although often considered to be independent, different mechanisms cooperate closely in regulating the epigenome [17]. Because the deregulation of such epigenetic mechanisms is implicated in cancer development, in-depth characterization of the cancer epigenome boosted the understanding of tumor initiation and progression [14].

Figure 1.

Main epigenetic mechanisms involved in gene expression regulation. DNA methylation consists of the addition of a methyl group in cytosine present in a cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG) dinucleotide. Histone post-translational modifications comprise alterations in histone tails such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination. Histone variants differ in few amino acids from canonical histones and regulate chromatin remodeling and histone post-translational modifications. Chromatin-remodeling complexes regulate the nucleosome structure by removing, relocating, and shifting histones.

Early in their development and progression, several epigenetic mechanisms are disrupted in BC [18]. For example, mutations in EP300 and CREBBP, two chromatin-remodeling genes, led to the inactivation of the complex’s histone-acetyltransferase domain, resulting in changes in chromatin conformation. Furthermore, a gene expression signature allied with the loss of histone acetyltransferase activity was associated with more aggressive bladder tumors [19]. Interestingly, 89% of MIBC lesions display mutations in the histone-modifying genes [20]. Specifically, a high mutation rate was found in KMT2D (also known as MLL2) gene and in KDM6A (also referred as UTX), which encode a histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferase and a histone lysine demethylase, respectively [21,22,23]. The most explored epigenetic mechanism is DNA methylation [18,24]. By comparing methylation patterns, Wolff et al. found global hypomethylation in NMIBC, whereas hypermethylation patters were more commonly found in invasive tumors, supporting the concept that DNA methylation has an important role in BC development and aggressiveness, constituting a putative target for anti-cancer therapy [24,25].

The main goal of this review is to summarize the impact of aberrant DNA methylation in BC, focusing on therapeutic strategies that target this epigenetic alteration, based on the information provided by preclinical studies, both in vitro and in vivo, and clinical trials.

2. DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is the covalent addition of a methyl group at the 5-position carbon of cytosine in a cytosine–phosphatidyl–guanine (CpG) dinucleotide [17]. Methylation occurs mainly at CpG islands—CpG-rich regions (at least 50% of cytosines and guanines) in the genome with a size larger than 200 bp [26,27]. Moreover, methylation can also be found in repetitive sequences such as retrotransposon elements and centromeres, in the X chromosome (leading to its inactivation) and genomic imprinting [28]. Approximately 29,000 CpG islands can be found in the human genome, most commonly in the promoter regions, close to the transcription starting site (TSS) or first exons [27]. Remarkably, 75% of cytosines in CpG dinucleotides dispersed throughout the genome are methylated, whereas cytosines of CpG islands located within gene promoters remain mostly hypomethylated [27,29]. Promoter DNA methylation is classically associated with transcription repression by inducing binding of transcriptional repressors or hampering binding of transcriptional factors [15,17]. In fact, a family of methyl-CpG-binding proteins (MBPs) intervenes in gene silencing by binding to methylated CpGs and recruiting histone modifier enzymes to establish histone post-translation modifications, which further sustain transcriptional repression [30]. DNA methylation can also be found in CpG island shores, 2-kb areas upstream of a CpG island, displaying lower CpG dinucleotide density. CpG island shore methylation is also associated with transcriptional repression [31]. On the other hand, methylation in the gene body was shown to stimulate transcription elongation and to have an impact on splicing, with exons disclosing higher methylation levels than introns [28,32]. Furthermore, tissue-specific methylation seems to be more frequent in intragenic CpG islands [33]. CpG islands in enhancers also influence gene regulation, i.e., hypermethylation is associated with loss of enhancer marks resulting in gene silencing [34].

DNMTs catalyze the covalent bond between the methyl group donated by S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) and the unmethylated CpG dinucleotide at the fifth position of the cytosine by positioning the target base into the catalytic pocket of the enzyme using a base-flipping mechanism [35,36,37]. Five DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are encoded by the human genome, including DNMT1, DNMT2, DNMT3a, DNMT3b, and DNMT3L [37,38,39]. Specifically, DNMT3a and DNMT3b catalyze de novo DNA methylation, whereas DNMT1 preferentially maintains methylation patterns already existing by copying methylation patterns in the course of replication during embryonic development [37,38,39]. DNMT2 and DNMT3L do not display DNMT catalytic activity, serving as post-transcriptional gene regulation and cofactors of other DNMTs, respectively. By contrast, ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes mediate active DNA demethylation through 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) [40,41], followed by deamination by activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic subunit 1 (APOBEC1) proteins, and base or nucleotide excision repair [17,42,43].

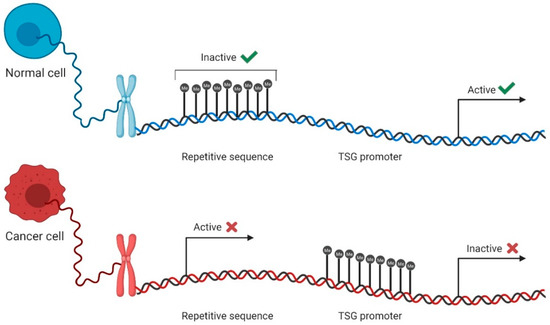

Overall, the cancer epigenome is characterized by global hypomethylation, which contributes to the overexpression of proto-oncogenes, an increased mutation rate, and the loss of imprinting [44]. Indeed, a decrease from 80% to 40–60% in the methylation levels from normal to cancer cells was observed [44,45]. More specifically, genomic repetitive regions become unmethylated, stimulating early cancer events through chromosomal instability that result in increased mutation rates, chromosomal rearrangements, and centromere instability (Figure 2) [46,47]. Simultaneously, the promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes (TSG) is also a frequent event in cancer cells [48], thus contributing to processes such as invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis [44]. Typically, 5–10% of CpG islands at gene promoters are methylated in cancer (Figure 2) [44].

Figure 2.

DNA methylation in normal and cancer cells. In normal cells, most repetitive sequences are methylated, whereas the promoters of tumor suppressor genes (TSG) stay unmethylated, remaining active and leading to gene expression (green check mark). Contrarily, in cancer cells, repetitive sequences become unmethylated and active, contributing to genomic instability, and TSG promoters become methylated, inactivating these genes and promoting cell aggressiveness and escape (red cross mark).

DNA methylation is a known contributor to BC development [49]. Hence, aberrant DNA methylation was proposed as a promising biomarker for BC detection, prognosis, and therapeutic target [50,51]. For example, a panel comprising HOXA9, PCDH17, POU4F2, and ONECUT2 methylation detected BC with 90.5% sensitivity and 73.2% specificity in urine samples from Chinese patients presenting hematuria, leading the authors to estimate that about 60% of cystoscopies could be avoided [52]. Furthermore, a methylation panel composed of GDF15, TMEFF2, and VIM discriminated BC patients from healthy controls and prostate or renal cancer patients with a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 90% in urine sediment samples [53], whereas the UroMark assay based on 150 CpG loci detected BC in voided urine samples with 98% sensitivity and 97% specificity [54]. On the other hand, in an analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded primary BC tissue samples, methylation of SFRP5 was associated with recurrence and CACNA1G was associated with BC progression [55]. Moreover, DNMTs were shown to be overexpressed in BC, representing an attractive target for anti-cancer therapies [56].

3. DNMT Inhibitors

As previously stated, DNA methylation is a reversible alteration that contributes to BC development and progression, and DNMTs are overexpressed in this tumor type [49,56]. Thus, DNMTs constitute attractive targets for cancer treatment, and several “epidrugs” are already approved for the treatment of specific conditions [57]. Indeed, 5-azacytidine (or azacytidine (5-aza, Vidaza®)) and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (or decitabine (DAC, Dacogen®)) are two DNMT inhibitors approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndrome, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) [30,57,58]. DNMT inhibitors can be classified, depending on their mechanism of action, as nucleoside and non-nucleoside analogues [24].

3.1. Nucleoside Analogues

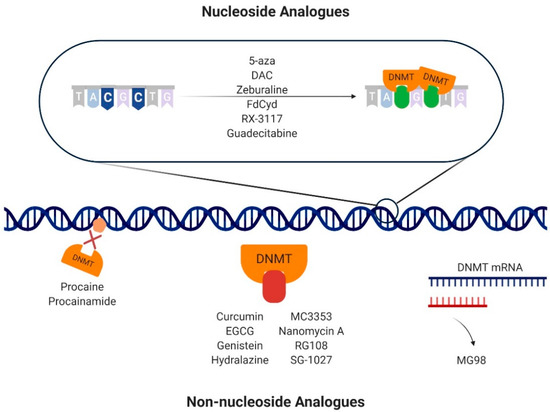

Nucleoside analogues (or cytidine analogues) are a group of compounds that integrate into DNA instead of cytosine, resulting in the formation of a covalent bond with a DNMT in the carbon-6 position of the cytosine during the synthesis (S) phase of the cell cycle [57,59] (Figure 3; Figure S1, Supplementary Materials). 5-Aza and DAC are the nucleoside analogues most commonly used as therapeutic agents in cancer [60], with DAC having 90% more demethylating power than 5-aza [61]. Although their mode of action remains controversial, several mechanisms were proposed [59,62,63,64]. After the cellular uptake, mediated by nucleoside transporters, nucleoside analogues are activated through conversion to 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine-5′-triphosphate, a substrate for the DNA replication machinery, to be incorporated in DNA, replacing cytosine [59]. At that point, DNMTs recognize azacytosine–guanine dinucleotides and catalyze the methylation reaction by forming a covalent bond with the cytosine ring [65,66]. Since azacytosine has a nitrogen substituting the carbon at position 5, the covalent bond cannot be broken, resulting in DNMT inactivation [59]. In addition to DNMT degradation, the complex formed between DNA and DNMT prompts DNA damage by causing double-strand breaks, leading to loss of methylation marks [59,67]. DAC and 5-aza seem to cause different effects in cancer cells. Although they both lead to a depletion of DNMT1 and a decrease in DNA methylation levels in non-small-cell lung cancer cells, 5-aza induces DNA damage, apoptosis, and cell arrest at phase sub-gap 1 (G1), whereas DAC increases the number of cells arrested in gap 2 (G2)/mitosis (M). As a consequence, their effects on gene expression are also different, with 5-aza decreasing the expression of genes related to cell cycle and metabolic processes, while DAC upregulates genes related to cell differentiation [63]. Furthermore, response rates to DAC treatment in AML patients with p53 mutations were higher in comparison with patients with wild-type p53, showing that mutations in p53 may play a role in epigenetically mediated cell death after DAC treatment [62,68]. Remarkably, phosphorylation of DNMT1 by protein kinase δ leads to its faster degradation after treatment with 5-aza or DAC, constituting another possible mechanism via which hypomethylation is achieved [64]. However, 5-aza and DAC are characterized by poor bioavailability, since they are easily degraded by hydrolysis in aqueous acidic or basic environments and have a limited half-life [59,69]. Indeed, both compounds can be deaminated by cytidine deaminase and converted into 5-azauridine, which results in their inactivation [70]. Furthermore, DAC is only incorporated into DNA, whereas 5-aza is incorporated into both DNA and RNA [70] and, since none of the compounds target specific DNMT isoforms, DAC and 5-aza cause significant side effects [70]. Thus, several alternative nucleoside analogues were developed to overcome these limitations.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of action of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors. The nucleoside analogues 5-azacitydine (5-aza), decitabine (DAC), zebularine, 5′-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine (FdCyd), RX-3117, and guadecitabine are integrated into DNA instead of cytosine. When DNMTs bind, a covalent bond is formed between the DNMT and the cytosine analogue. The non-nucleoside analogues have different mechanism of action to achieve inhibition of DNA methylation. Specifically, procaine and procainamide bind directly to the DNA, impeding DNMT binding. Curcumin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), genistein, hydralazine, MC3353, nanomycin A, RG108, and SG-1027 bind directly to the catalytic pockets of DNMTs, hampering their action. MG98 is an oligodeoxynucleotide that binds to the DNMT1 messenger RNA (mRNA) by base pair complementarity, impeding its translation.

Zebularine is a cytidine analogue that lacks the amino group at position 4 of the pyrimidine ring. It displays high stability as it inhibits both DNMTs and cytidine deaminase, and it is stable in acidic and neutral pH, enabling oral administration [71]. Moreover, zebularine has low cytotoxicity, which might translate into longer treatments with low doses to maintain a demethylated state [71], as well as an apparent specificity for cancer cells and not fibroblasts [72,73]. Zebularine leads to S-phase delay and cell death in mesothelioma cells [72], causes formation of replication-dependent double-strand DNA breaks [74], and enhances colon cancer cell immunogenicity [75]. Nevertheless, high concentrations of zebularine are needed to achieve demethylation levels similar to those of DAC since it forms a reversible complex with DNMTs, with slow dissociation kinetics [76], hindering the transition to clinical practice [57,71]. 5′-Fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine (FdCyd) is a fluoropyrimidine nucleoside analogue with a mechanism of action similar to 5-aza and DAC [24]. However, it is more stable and induces less toxicity compared to 5-aza and DAC [77]. As these nucleoside analogues are rapidly metabolized, combining them with tetrahydrouridine (THU), a cytidine deaminase inhibitor, was proposed to overcome such limitation [78,79,80,81]. Indeed, co-administration of FdCyd and THU induced plasma concentrations of FdCyd in patients similar to those established as needed for inhibiting DNA methylation in vitro [80].

SGI-110 or guadecitabine is a second-generation hypomethylating agent containing DAC coupled with a deoxyguanosine—a CpG dinucleotide analogue [70]. It is not a substrate for cytidine deaminase, a fact that increases the compound’s exposure time without being inactivated [82]. Guadecitabine was tested in several clinical trials. Specifically, a combination of guadecitabine and irinotecan was shown to be safe and to possess clinical activity in metastatic colorectal cancer patients in a phase I dose escalation study [83]. Likewise, guadecitabine was clinically active in intermediate- and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, namely, in patients who did not respond to the currently approved demethylating agents [84]. More recently, an oral formulation of 5-aza, CC-486, was developed and tested in several clinical trials [85,86,87,88]. Some advantages of the oral route include a more convenient and easier administration to monitor, a high exposure time to the drug, and the elimination of local reactions [88]. Although a combination treatment with CC-486 and pembrolizumab was not effective in improving progression-free survival (PFS) in non-small-cell lung cancer patients [86], CC-486 as a single treatment showed clinical activity in nasopharyngeal cancer in a phase I clinical trial [87]. Furthermore, extending doses of CC-486 in low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes patients might provide an effective long-term treatment [88]. RX-3117 (fluorocyclopentenylcytosine) is a novel cytidine analogue with a modified ribose molecule [89]. To be incorporated into DNA or RNA, the RX-3117 molecule is firstly activated through transformation into a triphosphate form by uridine–cytidine kinase 2 [90]. Although RX-3117 is not a substrate for cytidine deaminase [89], other enzymes such as NT5C3 may have a role in breaking an intermediate monophosphate form, resulting in RX-3117 inactivation [90]. RX-3117′s anti-tumor effects were evaluated in nine different xenograft mouse models and showed promise for the treatment of tumors that are sensitive and resistant to gemcitabine [91].

3.2. Non-Nucleoside Analogues

Although nucleoside analogues are potent inhibitors of DNA methylation, they lack specificity, resulting in important side effects. To overcome this, non-nucleoside molecules were developed in the last few years. Non-nucleoside analogues comprise all DNMT inhibitors whose mechanism is independent of DNA incorporation [92], including DNA binders, oligonucleotides, natural compounds, SAM competitors, and repurposed drugs, i.e., drugs that were designed for a specific target and treatment but were found to have a novel therapeutic effect [92,93] (Figure 3; Figure S1, Supplementary Materials).

Procaine and procainamide, derivatives of 4-aminobenzoic acid, are FDA-approved drugs as anesthetic and anti-arrhythmic, respectively [94,95]. Both drugs were shown to cause global DNA hypomethylation in MCF7 cells inducing cell growth inhibition [94]. Additionally, procaine reduces the activity of DNMT1 and DNMT3a without influencing their expressions [96]. By directly binding to DNA, procaine and procainamide hamper DNMTs binding, leading to decreased global DNA methylation levels, although to a lesser extent when compared to DAC [94,96]. The antibiotic nanaomycin A also induces global hypomethylation and reactivates TSGs such as Ras association domain family 1 isoform A (RASSF1A) [97]. Remarkably, nanaomycin A showed specificity for DNMT3b inhibition by interacting with key amino-acid residues of this enzyme [98]. Hydralazine is an arterial vasodilator approved for the treatment of severe hypertension and heart failure [99]. It causes re-expression of TSGs by reversing promoter hypermethylation, both in cancer cell lines and in primary tumors [100]. Hydralazine inhibits DNA methylation, although weakly, by interacting with the DNMT active site [99]. Furthermore, hydralazine treatment caused a decrease in cell growth and invasiveness, increased apoptosis, cell-cycle arrest, and lowered DNMT messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein levels [101]. On the other hand, the combined treatment with hydralazine and valproic acid also demonstrated anti-metastatic effects, both in vitro and in vivo [102], and it showed potential clinical benefit in patients with disease progression under chemotherapy [103] including advanced cervical cancer patients [104].

Oligodeoxynucleotides that bind a target mRNA by base pair complementarity also show promise as DNMTs inhibitors [105]. In particular, MG98 is a second-generation 20-nucleotide antisense oligonucleotide that binds specifically to DNMT1 mRNA, causing a decrease in DNMT levels [105]. In an initial phase I clinical trial, MG98 was not well tolerated in high doses, and its anticancer effects were not observed in patients with solid tumors [106]. The lack of clinical activity was also observed in patients with high-risk myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia [107]. However, in another clinical trial in patients with advanced solid tumors using escalating doses, MG98 was well tolerated and showed early clinical benefit [108], similarly to a combination of MG98 and interferon (IFN) α-2β in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma [109]. RG108 is a synthetic molecule considered to be a SAM competitor that targets the binding pockets of DNMTs, establishing covalent bonds and leading to inhibition of their enzymatic activity [110]. Treatment with RG108 caused inhibition of DNMTs and cell growth, and it increased apoptosis in endometrial and prostate cancer cell lines [111,112]. SGI-1027 is a quinolone-based molecule which directly binds to the cofactor-binding site of DNMT3a and to both the cofactor- and the substrate-binding sites of DNMT1 [113]. Treatment of RKO cells with SGI-1027 resulted in demethylation and re-expression of TSGs including p16, mutL homolog 1(MLH1), and metalloproteinase inhibitor 3 (TIMP3), with no significant toxicity [114]. Another quinolone-based molecule, MC3353, caused cell arrest and decreased cell viability in a panel of different cancer cell lines. Furthermore, E-cadherin mRNA and protein levels increased while a reduction of matrix metalloproteinase levels was observed in PC-3 and HCT116 cells, hampering their epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [115].

Several natural compounds were shown to have DNMT inhibitory activity [24]. The natural polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), found in green tea, was shown to inhibit DNMT activity by interacting with the enzyme catalytic pocket, reactivating the expression of several TSGs by reversing the hypermethylation status [116,117]. EGCG also decreased cell viability, migration and invasion of breast cancer cells, and SCUBE2 methylation by decreasing DNMT expression and activity [118]. Genistein is an isoflavone present in soybeans which displays anti-cancer activity [24]. In prostate tissue cancer samples, differences in methylation patterns and expressed genes were found comparing patients with genistein supplementation prior to prostatectomy and those receiving placebo [119]. After genistein treatment, DNA methylation levels decreased in several promoters of TSGs such as ATM, APC, PTEN, and SERPINB5, with a concomitant increase in the mRNA levels of those genes. Genistein interacts with the catalytic domain of DNMT1, competing with hemi-methylated DNA for the catalytic pocket [120]. Furthermore, in colon cancer cells, genistein demethylated WIF1 and decreased invasiveness and migration of cancer cells by reducing expression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 [121]. Curcumin, a polyphenol compound with anti-inflammatory properties, also influences methylation status. In colorectal cancer cells, exposure to curcumin led to demethylation of specific CpG loci without inducing global methylation changes [122].

4. DNA Methylation as a Therapeutic Target in BC

4.1. Preclinical Studies

A summary of the preclinical studies testing DNMT inhibitors in BC is depicted in Table 1. The effects of 5-aza were evaluated in cell lines in vitro and in a tumor xenograph model. 5-Aza was shown to inhibit cell proliferation and arrest cells at G0/G1, whereas volume and weight of tumor xenografts in mice were reduced. Interestingly, DNMT3a and DNMT3b expressions were also reduced after 5-aza treatment, causing the re-expression of hepaCAM, a TSG [56]. DAC treatment also led to an increase in hepaCAM expression in T24 and BIU87 cells, associated with arrest at G0/G1 phase [123]. In a canine model of invasive urothelial carcinoma, 5-aza disclosed anti-tumor effects, with 22.2% of the dogs demonstrating partial response and 50% depicting stable disease [124].

Table 1.

Summary of pre-clinical studies targeting DNMTs in bladder cancer (BC).

Non-toxic concentrations of DAC were used to treat four BC cell lines in order to evaluate the impact of hypomethylation in the BC cell transcriptome. Notch receptor 1 (NOTCH1) expression increased after treatment with DAC, in parallel with 50% demethylation of the promoter and enhancer regions. Interestingly, DAC-treated cells displayed morphological changes, i.e., cell enlargement compared to the controls. To explore these effects, the active intracellular domain of NOTCH1, ICN1, was overexpressed in cell lines and a decrease in cell proliferation was observed. Moreover, there was an increase of interleukin (IL)-6, probably due to a rise in ICN1 expression and double-stranded RNA levels [125]. ICN1 overexpression also led to a decrease in basal stem-like cells, as assessed by the decreased cytokeratin 5 (CK5) levels, contributing to a more differentiated cell state [125], which may prevent BC progression [126]. DAC was also shown to inhibit cell proliferation, migration, and invasiveness, inducing apoptosis in T24 cells while increasing the expression of the TSG Maspin [127]. Another gene that appears to be regulated by methylation in BC is BTG2. After treating EJ cells with DAC, BTG anti-proliferation factor 2 (BTG2) expression increased mainly due to DNMT1 inhibition, and cell growth decreased. Furthermore, H3K9me2 levels decreased, whereas H3K4me3 increased, leading to an open chromatin state in the promoter and intronic region of BTG2 [128]. Apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 (APAF-1) and death associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK-1) expressions also increased after DAC treatment in both RT4 and T24 cells, whereas zebularine caused an increased expression of those genes in cell line T24, which is p53 mutated [129]. Remarkably, Cheng et al. showed that treatment of T24 cells with zebularine for 48 h was not enough to maintain a long-term hypomethylated state and sustained p16 expression, as the percentage of methylation at day 0 was 97% and decreased to 75% at day 3. Inversely, a continuous treatment for 40 days, renewing dosage every three days, repressed cell growth and sustained p16 expression, while DNMT1 recovery was null. However, sequential treatment with DAC and zebularine was the most effective in increasing and retaining p16 expression, maintaining promoter hypomethylation, and hampering re-methylation patterns observed before treatment [130]. Therefore, to increase treatment efficacy with this type of drug, a prolonged treatment seems to be pivotal.

The epigenetic regulation of Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (Wif-1), an antagonist of the Wnt pathway, important for carcinogenesis, was explored in four BC cell lines. DAC treatment led to increased Wif-1 mRNA levels with a simultaneous decrease in promoter methylation levels. Furthermore, Wif-1 expression was primarily regulated by DNA methylation and not genetic alterations [131]. DAC treatment in T24 cells induced the expression of several genes related to the IFN pathway, which could theoretically lead to inhibition of tumor cell growth [132]. Interestingly, Velicescu et al. showed that de novo methylation does not occur in non-dividing BC cells. Treating T24 cells with DAC allows for cell arrest at G0/G1 and determines how much time is necessary for re-methylation to occur. Indeed, no re-methylation was found in CpG islands, whereas various degrees of methylation reappeared in CpG poor regions. Furthermore, DNMT1 and 3b3 protein levels were not detected, whereas DNMT3a mRNA levels were maintained after day 10 of the experiment. This result demonstrates that DNMT3a might catalyze a de novo methylation in CpG poor regions outside the S phase of the cell cycle [133]. In another study, the carcinogen N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine) (BBN) was used to induce bladder tumors in mice. These tumors showed downregulation of several genes including GSTM1, which seems to be regulated, in part, by DNA methylation, since treatment with DAC in 5637 cells increased GSTM1 expression [134]. Kawakami et al. reported for the first time that MSH3 epigenetic regulation by means of DNA methylation might contribute to gene silencing, being implicated in BC carcinogenesis [135].

Recently, a study comprising a wide range of different cancer cell lines, containing BC, showed that DNMT inhibitors, including DAC and 5-aza, increase methylation levels throughout the cancer epigenome. Specifically, in BC cell lines, DAC treatment increased methylation levels of 616 common CpGs and decreased methylation levels of 590 different CpGs, demonstrating that the DNMT inhibitor mechanism of action is complex and requires further exploration [136].

After treatment with S110, global methylation levels decreased, concomitantly with increased p16 expression [137]. The effects of S110 in vivo were also assessed in a tumor xenograft mouse model using EJ6 cells. Tumor-free animals tolerated S110 better than DAC, with less weight loss and mortality. S110 failed to cause reduction in tumor sizes, yet their growth rate was lower and p16 expression was induced [138]. The development of DAC and 5-aza variants could potentially increase their half-life, improving bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy.

Procainamide and hydralazine inhibitory effects on DNA methylation were studied in T24 cells. Both compounds decreased the methylation levels of TSGs p16 and RARβ, which associated with their re-expression, both at the transcript and at the protein levels. Interestingly, hydralazine treatment maintained p16 reactivation for longer than DAC [100]. A novel strategy to inhibit DNMT1, using an essential enzyme for cancer cell viability [139] highly expressed in BC [140], was proposed using DNAzymes. A DNAzyme is a stable DNA molecule with catalytic activity that targets specific RNA molecules leading to their destruction [141,142]. The DNAzyme DT433, constructed and selected to target DNMT1, displayed effects that were similar to those of 5-aza. Additionally, DT433 led to an increase in p16 expression and inhibition of cell proliferation [142]. Novel strategies applying repurposed drugs or DNAzymes to achieve DNMT inhibition constitute interesting alternatives to the demethylating drugs already approved. On the one hand, DNAzymes showed that increasing specificity toward the target may be achieved, whereas repurposed drugs, with negligible toxicity and known safety profiles, may be administered for longer periods and be considered as the next step for DNA methylation inhibition as anti-cancer therapy.

4.2. Combination Studies

The anti-tumor effects of 5-aza, trichostatin A (TSA), and FK228 (the latter is a class I histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor) were evaluated individually and in combination in a set of BC cell lines, as well as xenograft and orthotopic mouse models. The combination 5-aza and FK228 was shown to be toxic for 90% of the BC cells, inducing apoptosis and decreasing the G2/M cell population. The same combination in in vivo models led to a decrease in tumor size, mainly due to the effect of FK228 alone [147]. Combination treatments using 5-aza and TSA also reduced the cell number and a shift in the expression of proteins that regulate the cell cycle in canine BC cell lines [148]. More recently, combination of DAC and entinostat, another HDAC1 inhibitor, was tested in bladder cell lines, including two cisplatin-sensitive (J82 and RT112) and one cisplatin-resistant (J82CisR) cell lines, as well as one urothelial cell line isolate from normal tissue (HBLAK). The combination treatment did not revert cisplatin resistance of J82CisR, although treatment with both drugs promoted cell growth arrest. Additionally, increased apoptosis was observed, related to caspases 3 and 7, prompting cell arrest at G2/M transition. Forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) expression increased after the combination treatment, as well as BIM and p21, along with a decrease in survivin expression [149].

Several strategies using epigenetic drugs were devised to overcome chemoresistance and increase therapy success. Ramachandran et al. showed that pre-treatment with 5-aza followed by cisplatin or docetaxel exposure increased cytotoxicity in BC cells. Moreover, in UMUC3 cells that developed resistance to cisplatin or docetaxel in vitro, pre-treatment with 5-aza resulted in 44% and 55% of cytotoxicity in cisplatin- and docetaxel-resistant cells, respectively, in opposition to 2% with no pre-treatment [150]. Pre-treatment with DAC also enhanced cytotoxicity of cisplatin and doxorubicin in BC cells. Furthermore, RASSF1A expression was observed concomitantly with activation of the Hippo pathway [151]. Interestingly, UMUC14, RT4, 96-1, and 97-1 cell lines displayed low sensitivity to cisplatin, being associated with high HOXA9 methylation levels. This was also verified in MIBC patients in which high HOXA9 methylation levels were associated with resistance to chemotherapy. In line with other studies, DAC led to a 4–5-fold decrease in half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for cisplatin, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and etoposide in BC cells [152]. Wu et al. demonstrated for the first time that DAC treatment reduced the cancer stem-cell population in mice. Specifically, in a BNN-induced mouse model of BC, DAC alone or in combination with cisplatin or gemcitabine led to a decline in the keratin 14 (KRT14)+ cell population, which originates from the bladder urothelium [153]. Consistently, the percentage of SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2)+ cell population assumed to be responsible for the spread of the tumor [154] was also lower. Curiously, the percentage of such cells increased in mice treated with chemotherapy only [155]. These results were replicated in patient sample-derived xenografts, demonstrating that a combination treatment of DAC with chemotherapeutic agents might constitute a valuable option for BC therapy [155]. Another study showed that a quadruple combination therapy comprising gemcitabine, cisplatin, DAC, and TSA increased apoptosis via cyclin D1 (CCND1) downregulation, DNA fragmentation, and caspase 3 expression in T24 cells. On the other hand, a cell proliferation reduction and lower BCL2L1 mRNA levels were observed after treatment [156].

A novel dual inhibitor, CM-272, targeting G9a, a histone methyltransferase that catalyzes H3K9me2, and DNMTs demonstrated activity against a wide range of cancer cells [157]. Specifically, treatment of hematologic malignancies cell lines with concentrations in the nanomolar range led to a global decrease in H3K9me2 and 5-methylcytosine levels, a reduction in cell proliferation, induction of cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis, and a decrease in TSG promoter methylation. Interestingly, CM-272 also induced an IFN-γ type I response and immunogenic cell death. In an in vivo mouse model, CM-272 was safe to administer, with an increased overall survival of the treated mice [157]. Furthermore, CM-272 was also active against hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines [158]. Recently, the effects of CM-272 were evaluated in in vitro and in vivo models of BC. CM-272 in combination with cisplatin led to inhibition of cell proliferation, which was also verified in a BC xenograft mouse model, leading to a decreased tumor growth, whereas apoptosis and autophagy were increased [159]. These effects were also observed in a quadruple-knockout transgenic mouse model of advanced BC. Remarkably, BC cells treated with CM-272 showed upregulation of genes linked to the immune response, including IFN-α and γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, probably through induction of an endogenous retrovirus response [159]. Taking into account these results, the combination of CM-272 with anti-PD-L1 in the quadruple-knockout mouse model was explored. A sustained response to the combination treatment was observed, with the number of animals developing tumors or metastases being lower in the combination group when compared with the group treated with anti-PD-L1 monotherapy [159]. Remarkably, CM-272 treatment led to an immune reactivation of tumor cells, turning “cold” tumors into “hot” ones [159]. A brief overview of the main studies exploring the combination therapies in BC experimental models can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of combination studies targeting DNMTs in BC.

4.3. Clinical Studies

A non-randomized multicenter phase II study evaluated the effects of FdCyd in THU [80,162]. The safety, maximum tolerated dose (MTD), pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of this combination were determined in a previous phase I clinical trial (FyCyd 100 mg/m2/day and THU 350 mg/m2/day) [81]. Patients with metastatic or unresectable breast cancer (n = 29), head and neck cancer (n = 21), non-small-cell lung cancer (n = 25), and urothelial cell carcinoma (n = 18) which endured progression after at least one line of standard therapy were included in this study. The combination was well tolerated, and urothelial carcinoma patients showed some clinical responses, with an objective response rate (ORR) of 5.6%, a progression-free survival (PFS) of 3.6 months, and a four-month PFS probability of 42%. Furthermore, increased p16 expression was observed in cytokeratin-positive circulating tumor cells (CTCs) of some patients, although it did not associate with clinical response (Table 3) [162].

Table 3.

Clinical trials in BC using DNMT inhibitors.

The pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and clinical relevance of combining 5-aza and sodium phenylbutyrate, a first-generation HDAC inhibitor, was assessed in 34 patients with refractory solid tumors with no curative options, including two BC patients. Twenty-seven patients were eligible to proceed with treatment in three different regiments. The treatment was well tolerated with the most common toxicity effects including neutropenia, anemia, nausea, vomiting, transaminase elevation, and edema. The results of the study were mostly disappointing, with only one leiomyosarcoma patient displaying stable disease for 4.5 months and the rest disclosing disease progression. Although inhibition of DNMT activity was observed in two patients, this drug combination failed to show clinical benefit (Table 3) [163].

In a phase Ib clinical trial, the effects of CC-486 to potentiate carboplatin or paclitaxel protein-bound particles (ABI-007) in 169 patients with relapsed or refractory solid tumors including BC were evaluated. Two arms were defined: arm A comprising treatment with CC-486 and carboplatin and arm B including combination treatment of CC-486 and ABI-007 [164]. Preliminary results showed that CC-486 (200 and 300 mg) was well tolerated, with treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) including anemia and neutropenia in about 50% of the patients in arm A and nausea/vomiting and peripheral neuropathy in patients of arm B. Five patients in arm A showed stable disease whereas three patients displayed partial response, with both combinations disclosing clinical value. Interestingly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were found to be hypomethylated. A recommended phase II dose (RP2D) study will comprise an expansion of cohorts and the combinations of 300 mg of CC-486 with carboplatin and 200 mg of CC-486 with ABI-007 [165].

Other clinical trials are at this date assessing the clinical benefit of combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with epigenetic drugs. In a recently completed study, the combination of pembrolizumab, epacadostat [indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1)-selective inhibitor], and 5-aza was assessed in a phase I and II trial enrolling 70 patients, including urothelial cancer patients [166]. Furthermore, in a currently recruiting phase II clinical trial, the biological and clinical efficacy of atezolizumab (which targets PD-L1) in combination with guadecitabine will be evaluated in 53 patients with checkpoint inhibitor-refractory or -resistant urothelial carcinoma (Table 3) [167].

5. Conclusions

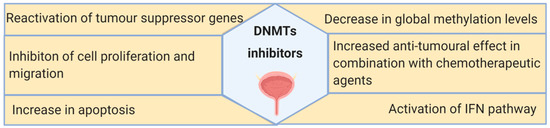

DNA methylation machinery is a promising target for BC treatment. Among the anti-tumor effects caused by DNMT inhibitors, the most frequently reported are reactivation of TSGs and inhibition of tumor cell growth (Figure 4). However, DNMT inhibitors still present several drawbacks that preclude their use for BC treatment, including the reversal of the inhibitory effects after drug withdrawal, short half-life, and significant toxicity. To overcome these, combination therapies comprising DNMT inhibitors, chemotherapeutic agents, and, more recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors might constitute a valid option for BC patients, as demonstrated by the currently ongoing clinical trials. Furthermore, the discovery of novel biomarkers to select patients more likely to respond to those therapies and the evaluation of the long-term effect of this class of compounds are required for the transition into clinical practice.

Figure 4.

Summary of the main effects of DNMT inhibitors observed in bladder cancer in vitro and in vivo models, as well as in clinical trials.

In conclusion, modulation of the epigenetic landscape of BC tumors constitutes an encouraging alternative to the currently available therapeutic strategies for BC patients, requiring further exploitation in a clinical trial setting, aiming at a future implementation in clinical practice.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/9/8/1850/s1: Figure S1. Chemical structure of nucleoside and non-nucleosides DNMT inhibitors.

Author Contributions

Reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript, S.P.N.; supervised the work and revised the manuscript, R.H., C.J., and J.M.P. All figures are original and were created with BioRender.com. All authors read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was co-funded by European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) grants from Science and Innovation (SAF2015-66015-R and PID2019-110758RB-I00 to J.M.P.) and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (RETIC no. RD12/0036/0009 to J.M.P., CIBERONC no. CB16/12/00228 to J.M.P.). S.P.N. is supported by an FCT Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia grant (SFRH/BD/144241/2019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, A.M.; Hahn, N.M.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Lerner, S.P.; Malmström, P.U.; Choi, W.; Guo, C.C.; Lotan, Y.; Kassouf, W. Bladder cancer. Lancet 2016, 388, 2796–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmunt, J.; Orsola, A.; Leow, J.J.; Wiegel, T.; De Santis, M.; Horwich, A. Bladder cancer: ESMO Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25 (Suppl. S3), iii40–iii48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.B.; Edge, S.; Greene, F.; Byrd, D.R.; Brookland, R.K.; Washington, M.K.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Compton, C.C.; Hess, K.R.; Sullivan, D.C.; et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA; American Joint Commission on Cancer: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Redelman-Sidi, G.; Glickman, M.S.; Bochner, B.H. The mechanism of action of BCG therapy for bladder cancer—A current perspective. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2014, 11, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Stat Facts: Bladder Cancer. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/urinb.html (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Mariotto, A.B.; Yabroff, K.R.; Shao, Y.; Feuer, E.J.; Brown, M.L. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, J.; Jerónimo, C.; Henrique, R. Targeting the immune system and epigenetic landscape of urological tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.A.; Birtle, A.; Crabb, S.; Huddart, R.; Small, D.; Summerhayes, M.; Jones, R.; Protheroe, A. From clinical trials to real-life clinical practice: The role of immunotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in advanced urothelial carcinoma. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2018, 1, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.Z.; Rouanne, M.; Tan, K.T.; Huang, R.Y.; Thiery, J.P. Molecular subtypes of urothelial bladder cancer: Results from a meta-cohort analysis of 2411 tumors. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Ochoa, A.; McConkey, D.J.; Aine, M.; Höglund, M.; Kim, W.Y.; Real, F.X.; Kiltie, A.E.; Milsom, I.; Dyrskjøt, L.; et al. Genetic alterations in the molecular subtypes of bladder cancer: Illustration in the cancer genome atlas dataset. Eur. Urol. 2017, 72, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.G.; Kim, J.; Al-Ahmadie, H.; Bellmunt, J.; Guo, G.; Cherniack, A.D.; Hinoue, T.; Laird, P.W.; Hoadley, K.A.; Akbani, R.; et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell 2017, 171, 540–556.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.D.; Issa, J.J. The promise of epigenetic therapy: Reprogramming the cancer epigenome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2017, 42, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baylin, S.B.; Jones, P.A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome—Biological and translational implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, R.L.; Licht, J.D. Targeting epigenetics in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 58, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voyias, P.; Patel, A.; Arasaradnam, R. Epigenetic biomarkers of disease. In Medical Epigenetics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Inbar-Feigenberg, M.; Choufani, S.; Butcher, D.T.; Roifman, M.; Weksberg, R. Basic concepts of epigenetics. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porten, S.P. Epigenetic alterations in bladder cancer. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2018, 19, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duex, J.E.; Swain, K.E.; Dancik, G.M.; Paucek, R.D.; Owens, C.; Churchill, M.E.A.; Theodorescu, D. Functional impact of chromatin remodeling gene mutations and predictive signature for therapeutic response in bladder cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature 2014, 507, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, C.D.; Alder, O.; Platt, F.M.; Droop, A.; Stead, L.F.; Burns, J.E.; Burghel, G.J.; Jain, S.; Klimczak, L.J.; Lindsay, H.; et al. Genomic subtypes of non-invasive bladder cancer with distinct metabolic profile and female gender bias in KDM6A mutation frequency. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 701–715.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ler, L.D.; Ghosh, S.; Chai, X.; Thike, A.A.; Heng, H.L.; Siew, E.Y.; Dey, S.; Koh, L.K.; Lim, J.Q.; Lim, W.K.; et al. Loss of tumor suppressor KDM6A amplifies PRC2-regulated transcriptional repression in bladder cancer and can be targeted through inhibition of EZH2. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaai8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Yan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, D.; Ye, Z.; Xu, H. Analysis of the role of mutations in the KMT2D histone lysine methyltransferase in bladder cancer. FEBS Open Bio. 2019, 9, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Magalhães, Â.; Graça, I.; Henrique, R.; Jerónimo, C. Targeting DNA Methyltranferases in Urological Tumors. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, E.M.; Chihara, Y.; Pan, F.; Weisenberger, D.J.; Siegmund, K.D.; Sugano, K.; Kawashima, K.; Laird, P.W.; Jones, P.A.; Liang, G. Unique DNA methylation patterns distinguish noninvasive and invasive urothelial cancers and establish an epigenetic field defect in premalignant tissue. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 8169–8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Caffo, B.; Jaffee, H.A.; Irizarry, R.A.; Feinberg, A.P. Redefining CpG islands using hidden Markov models. Biostatistics 2010, 11, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, H.J.; Esteller, M. CpG Islands in Cancer: Heads, Tails, and Sides. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1766, 49–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Paredes, M.; Esteller, M. Cancer epigenetics reaches mainstream oncology. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, R.; Gupta, S. Epigenetic modifications in cancer. Clin. Genet. 2012, 81, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasculli, B.; Barbano, R.; Parrella, P. Epigenetics of breast cancer: Biology and clinical implication in the era of precision medicine. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 51, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, V.V.; Grady, W.M. Epigenetics and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 8, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunakea, A.K.; Chepelev, I.; Cui, K.; Zhao, K. Intragenic DNA methylation modulates alternative splicing by recruiting MeCP2 to promote exon recognition. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 1256–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunakea, A.K.; Nagarajan, R.P.; Bilenky, M.; Ballinger, T.J.; D’Souza, C.; Fouse, S.D.; Johnson, B.E.; Hong, C.; Nielsen, C.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Conserved role of intragenic DNA methylation in regulating alternative promoters. Nature 2010, 466, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.G.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, J.K. Frequent hypermethylation of orphan CpG islands with enhancer activity in cancer. BMC Med. Genom. 2016, 9 (Suppl. S1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baubec, T.; Colombo, D.F.; Wirbelauer, C.; Schmidt, J.; Burger, L.; Krebs, A.R.; Akalin, A.; Schübeler, D. Genomic profiling of DNA methyltransferases reveals a role for DNMT3B in genic methylation. Nature 2015, 520, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timinskas, A.; Butkus, V.; Janulaitis, A. Sequence motifs characteristic for DNA [cytosine-N4] and DNA [adenine-N6] methyltransferases. Classification of all DNA methyltransferases. Gene 1995, 157, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyko, F. The DNA methyltransferase family: A versatile toolkit for epigenetic regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenbaum, Y.; Cedar, H.; Razin, A. Substrate and sequence specificity of a eukaryotic DNA methylase. Nature 1982, 295, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bestor, T.H.; Ingram, V.M. Two DNA methyltransferases from murine erythroleukemia cells: Purification, sequence specificity, and mode of interaction with DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 5559–5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahiliani, M.; Koh, K.P.; Shen, Y.; Pastor, W.A.; Bandukwala, H.; Brudno, Y.; Agarwal, S.; Iyer, L.M.; Liu, D.R.; Aravind, L.; et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science 2009, 324, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R.M.; Zhang, Y. TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation. Nature 2013, 502, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedar, H.; Bergman, Y. Programming of DNA methylation patterns. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, N.; Burns, D.M.; Blau, H.M. DNA demethylation dynamics. Cell 2011, 146, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylin, S.B.; Jones, P.A. Epigenetic determinants of cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a019505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.D.; Timp, W.; Bravo, H.C.; Sabunciyan, S.; Langmead, B.; McDonald, O.G.; Wen, B.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Diep, D.; et al. Increased methylation variation in epigenetic domains across cancer types. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.P.; Rand, K.N.; Molloy, P.L. Hypomethylation of repeated DNA sequences in cancer. Epigenomics 2010, 2, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Frigola, J.; Vendrell, E.; Risques, R.A.; Fraga, M.F.; Morales, C.; Moreno, V.; Esteller, M.; Capellà, G.; Ribas, M.; et al. Chromosomal instability correlates with genome-wide DNA demethylation in human primary colorectal cancers. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 8462–9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saif, I.; Kasmi, Y.; Allali, K.; Ennaji, M.M. Prediction of DNA methylation in the promoter of gene suppressor tumor. Gene 2018, 651, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandimalla, R.; van Tilborg, A.A.; Zwarthoff, E.C. DNA methylation-based biomarkers in bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2013, 10, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.K.; Lind, G.E.; Guldberg, P.; Dahl, C. DNA-methylation-based detection of urological cancer in urine: Overview of biomarkers and considerations on biomarker design, source of DNA, and detection technologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrão, N.A.; Monteiro-Reis, S.; Torres-Ferreira, J.; Antunes, L.; Leça, L.; Montezuma, D.; Ramalho-Carvalho, J.; Dias, P.C.; Monteiro, P.; Oliveira, J.; et al. MicroRNA promoter methylation: A new tool for accurate detection of urothelial carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, N.; Liu, S.; Lin, X.; Perschon, C.; Zheng, S.L.; Ding, Q.; Wang, X.; Na, R.; et al. HOXA9, PCDH17, POU4F2, and ONECUT2 as a urinary biomarker combination for the detection of bladder cancer in Chinese patients with hematuria. Eur. Urol. Focus 2020, 6, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.L.; Henrique, R.; Danielsen, S.A.; Duarte-Pereira, S.; Eknaes, M.; Skotheim, R.I.; Rodrigues, A.; Magalhães, J.S.; Oliveira, J.; Lothe, R.A.; et al. Three epigenetic biomarkers, GDF15, TMEFF2, and VIM, accurately predict bladder cancer from DNA-based analyses of urine samples. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5842–5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feber, A.; Dhami, P.; Dong, L.; de Winter, P.; Tan, W.S.; Martínez-Fernández, M.; Paul, D.S.; Hynes-Allen, A.; Rezaee, S.; Gurung, P.; et al. UroMark-a urinary biomarker assay for the detection of bladder cancer. Clin. Epigenet. 2017, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Baquero, R.; Puerta, P.; Beltran, M.; Alvarez-Mújica, M.; Alvarez-Ossorio, J.L.; Sánchez-Carbayo, M. Methylation of tumor suppressor genes in a novel panel predicts clinical outcome in paraffin-embedded bladder tumors. Tumour Biol 2014, 35, 5777–5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, E.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Quan, Z.; Wu, X.; Luo, C. 5-azacytidine inhibits the proliferation of bladder cancer cells via reversal of the aberrant hypermethylation of the hepaCAM gene. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Erdmann, A.; Halby, L.; Fahy, J.; Arimondo, P.B. Targeting DNA methylation with small molecules: What’s next? J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 2569–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, S.R.; Bullinger, L.; Rücker, F.G. Epigenetic therapy: Azacytidine and decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2018, 11, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stresemann, C.; Lyko, F. Modes of action of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitors azacytidine and decitabine. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 123, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, G.; Liang, G.; Aparicio, A.; Jones, P.A. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature 2004, 429, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.A.; Taylor, S.M. Cellular differentiation, cytidine analogues and DNA methylation. Cell 1980, 20, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.J. The p53 protein plays a central role in the mechanism of action of epigentic drugs that alter the methylation of cytosine residues in DNA. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 7228–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.N.; Hollenbach, P.W.; Richard, N.; Luna-Moran, A.; Brady, H.; Heise, C.; MacBeth, K.J. Azacitidine and decitabine have different mechanisms of action in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Lung Cancer (Auckl.) 2010, 1, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, J.; Ghoshal, K.; Motiwala, T.; Jacob, S.T. Novel insights into the molecular mechanism of action of DNA Hypomethylating agents: Role of protein kinase C δ in decitabine-induced degradation of DNA methyltransferase 1. Genes Cancer 2012, 3, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santi, D.V.; Norment, A.; Garrett, C.E. Covalent bond formation between a DNA-cytosine methyltransferase and DNA containing 5-azacytosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 6993–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; MacMillan, A.M.; Chang, W.; Ezaz-Nikpay, K.; Lane, W.S.; Verdine, G.L. Direct identification of the active-site nucleophile in a DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 11018–11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortusewicz, O.; Schermelleh, L.; Walter, J.; Cardoso, M.C.; Leonhardt, H. Recruitment of DNA methyltransferase I to DNA repair sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8905–8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, J.S.; Petti, A.A.; Miller, C.A.; Fronick, C.C.; O’Laughlin, M.; Fulton, R.S.; Wilson, R.K.; Baty, J.D.; Duncavage, E.J.; Tandon, B.; et al. TP53 and decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2023–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, C.; Fahy, J.; Halby, L.; Dufau, I.; Erdmann, A.; Gregoire, J.M.; Ausseil, F.; Vispé, S.; Arimondo, P.B. DNA methylation inhibitors in cancer: Recent and future approaches. Biochimie 2012, 94, 2280–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, A.; Arimondo, P.B.; Rots, M.G.; Jeronimo, C.; Berdasco, M. The timeline of epigenetic drug discovery: From reality to dreams. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.B.; Cheng, J.C.; Jones, P.A. Zebularine: A new drug for epigenetic therapy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2004, 32, 910–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemura, Y.; Satoh, M.; Hatanaka, K.; Kubota, S. Zebularine exerts its antiproliferative activity through S phase delay and cell death in human malignant mesothelioma cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Yoo, C.B.; Weisenberger, D.J.; Chuang, J.; Wozniak, C.; Liang, G.; Marquez, V.E.; Greer, S.; Orntoft, T.F.; Thykjaer, T.; et al. Preferential response of cancer cells to zebularine. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orta, M.L.; Pastor, N.; Burgos-Morón, E.; Domínguez, I.; Calderón-Montaño, J.M.; Huertas Castaño, C.; López-Lázaro, M.; Helleday, T.; Mateos, S. Zebularine induces replication-dependent double-strand breaks which are preferentially repaired by homologous recombination. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2017, 57, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Xue, Z.T.; Sjögren, H.O.; Salford, L.G.; Widegren, B. Low dose Zebularine treatment enhances immunogenicity of tumor cells. Cancer Lett. 2007, 257, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champion, C.; Guianvarc’h, D.; Sénamaud-Beaufort, C.; Jurkowska, R.Z.; Jeltsch, A.; Ponger, L.; Arimondo, P.B.; Guieysse-Peugeot, A.L. Mechanistic insights on the inhibition of c5 DNA methyltransferases by zebularine. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowher, H.; Jeltsch, A. Mechanism of inhibition of DNA methyltransferases by cytidine analogues in cancer therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2004, 3, 1062–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beumer, J.H.; Eiseman, J.L.; Parise, R.A.; Joseph, E.; Holleran, J.L.; Covey, J.M.; Egorin, M.J. Pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and oral bioavailability of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine in mice. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 7483–7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, G.L.; Moxley, T.E.; Kuentzel, S.L.; Manak, R.C.; Hanka, L.J. Enhancement by tetrahydrouridine (NSC-112907) of the oral activity of 5-azacytidine (NSC-102816) in L1210 leukemic mice. Cancer Chemother. Rep. 1975, 59, 459–465. [Google Scholar]

- Beumer, J.H.; Parise, R.A.; Newman, E.M.; Doroshow, J.H.; Synold, T.W.; Lenz, H.J.; Egorin, M.J. Concentrations of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine (FdCyd) and its cytotoxic metabolites in plasma of patients treated with FdCyd and tetrahydrouridine (THU). Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2008, 62, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, E.M.; Morgan, R.J.; Kummar, S.; Beumer, J.H.; Blanchard, M.S.; Ruel, C.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Carroll, M.I.; Hou, J.M.; Li, C.; et al. A phase I, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic evaluation of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine, administered with tetrahydrouridine. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 75, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; Roboz, G.J.; Kropf, P.L.; Yee, K.W.L.; O’Connell, C.L.; Tibes, R.; Walsh, K.J.; Podoltsev, N.A.; Griffiths, E.A.; Jabbour, E.; et al. Guadecitabine (SGI-110) in treatment-naive patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: Phase 2 results from a multicentre, randomised, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.; Wang, J.; Zahurak, M.; Gootjes, E.; Verheul, H.M.; Parkinson, R.; Kerner, Z.; Sharma, A.; Rosner, G.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; et al. A phase I trial of a guadecitabine (SGI-110) and irinotecan in metastatic colorectal cancer patients previously exposed to irinotecan. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 6160–6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Manero, G.; Roboz, G.; Walsh, K.; Kantarjian, H.; Ritchie, E.; Kropf, P.; O’Connell, C.; Tibes, R.; Lunin, S.; Rosenblat, T.; et al. Guadecitabine (SGI-110) in patients with intermediate or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: Phase 2 results from a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, e317–e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laille, E.; Savona, M.R.; Scott, B.L.; Boyd, T.E.; Dong, Q.; Skikne, B. Pharmacokinetics of different formulations of oral azacitidine (CC-486) and the effect of food and modified gastric pH on pharmacokinetics in subjects with hematologic malignancies. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 54, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.P.; Giaccone, G.; Besse, B.; Felip, E.; Garassino, M.C.; Domine Gomez, M.; Garrido, P.; Piperdi, B.; Ponce-Aix, S.; Menezes, D.; et al. Randomised phase 2 study of pembrolizumab plus CC-486 versus pembrolizumab plus placebo in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 108, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Hoff, D.D.; Rasco, D.W.; Heath, E.I.; Munster, P.N.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Isambert, N.; Le Tourneau, C.; O’Neil, B.; Mathijssen, R.H.J.; Lopez-Martin, J.A.; et al. Phase I study of CC-486 alone and in combination with carboplatin or nab-paclitaxel in patients with relapsed or refractory solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 4072–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Manero, G.; Gore, S.D.; Kambhampati, S.; Scott, B.; Tefferi, A.; Cogle, C.R.; Edenfield, W.J.; Hetzer, J.; Kumar, K.; Laille, E.; et al. Efficacy and safety of extended dosing schedules of CC-486 (oral azacitidine) in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 2016, 30, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.J.; Smid, K.; Vecchi, L.; Kathmann, I.; Sarkisjan, D.; Honeywell, R.J.; Losekoot, N.; Ohne, O.; Orbach, A.; Blaugrund, E.; et al. Metabolism, mechanism of action and sensitivity profile of fluorocyclopentenylcytosine (RX-3117; TV-1360). Investig. New Drugs 2013, 31, 1444–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, B.; El Hassouni, B.; Honeywell, R.J.; Sarkisjan, D.; Giovannetti, E.; Poore, J.; Heaton, C.; Peterson, C.; Benaim, E.; Lee, Y.B.; et al. RX-3117 (fluorocyclopentenyl cytosine): A novel specific antimetabolite for selective cancer treatment. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2019, 28, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.Y.; Lee, Y.B.; Ahn, C.H.; Kaye, J.; Fine, T.; Kashi, R.; Ohne, O.; Smid, K.; Peters, G.J.; Kim, D.J. A novel cytidine analog, RX-3117, shows potent efficacy in xenograft models, even in tumors that are resistant to gemcitabine. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 6951–6959. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Aguilera, O.; Depreux, P.; Halby, L.; Arimondo, P.B.; Goossens, L. DNA Methylation Targeting: The DNMT/HMT Crosstalk Challenge. Biomolecules 2017, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpakom, S.; Iorio, F.; Eyers, P.A.; Escott, K.J.; Hopper, S.; Wells, A.; Doig, A.; Guilliams, T.; Latimer, J.; McNamee, C.; et al. Drug repurposing: Progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Garea, A.; Fraga, M.F.; Espada, J.; Esteller, M. Procaine is a DNA-demethylating agent with growth-inhibitory effects in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 4984–4989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moreira-Silva, F.; Camilo, V.; Gaspar, V.; Mano, J.F.; Henrique, R.; Jerónimo, C. Repurposing old drugs into new epigenetic inhibitors: Promising candidates for cancer treatment? Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, T.C.; Li, C.F. Procaine is a specific DNA methylation inhibitor with anti-tumor effect for human gastric cancer. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 2440–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuck, D.; Caulfield, T.; Lyko, F.; Medina-Franco, J.L. Nanaomycin A selectively inhibits DNMT3B and reactivates silenced tumor suppressor genes in human cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 3015–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caulfield, T.; Medina-Franco, J.L. Molecular dynamics simulations of human DNA methyltransferase 3B with selective inhibitor nanaomycin A. J. Struct. Biol. 2011, 176, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas-Gonzalez, A.; Coronel, J.; Cetina, L.; González-Fierro, A.; Chavez-Blanco, A.; Taja-Chayeb, L. Hydralazine-valproate: A repositioned drug combination for the epigenetic therapy of cancer. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2014, 10, 1433–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Pacheco, B.; Trejo-Becerril, C.; Perez-Cardenas, E.; Taja-Chayeb, L.; Mariscal, I.; Chavez, A.; Acuña, C.; Salazar, A.M.; Lizano, M.; Dueñas-Gonzalez, A. Reactivation of tumor suppressor genes by the cardiovascular drugs hydralazine and procainamide and their potential use in cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 1596–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Graça, I.; Sousa, E.J.; Costa-Pinheiro, P.; Vieira, F.Q.; Torres-Ferreira, J.; Martins, M.G.; Henrique, R.; Jerónimo, C. Anti-neoplastic properties of hydralazine in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 5950–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cárdenas, E.; Taja-Chayeb, L.; Trejo-Becerril, C.; Chanona-Vilchis, J.; Chávez-Blanco, A.; Domínguez-Gómez, G.; Langley, E.; García-Carrancá, A.; Dueñas-González, A. Antimetastatic effect of epigenetic drugs, hydralazine and valproic acid, in Ras-transformed NIH 3T3 cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 8823–8833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelaria, M.; Gallardo-Rincón, D.; Arce, C.; Cetina, L.; Aguilar-Ponce, J.L.; Arrieta, O.; González-Fierro, A.; Chávez-Blanco, A.; de la Cruz-Hernández, E.; Camargo, M.F.; et al. A phase II study of epigenetic therapy with hydralazine and magnesium valproate to overcome chemotherapy resistance in refractory solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel, J.; Cetina, L.; Pacheco, I.; Trejo-Becerril, C.; González-Fierro, A.; de la Cruz-Hernandez, E.; Perez-Cardenas, E.; Taja-Chayeb, L.; Arias-Bofill, D.; Candelaria, M.; et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase III trial of chemotherapy plus epigenetic therapy with hydralazine valproate for advanced cervical cancer. Preliminary results. Med. Oncol. 2011, 28 (Suppl. S1), S540–S546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, R.J. Inhibition of DNA methylation by antisense oligonucleotide MG98 as cancer therapy. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2007, 5, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.J.; Gelmon, K.A.; Siu, L.L.; Moore, M.J.; Britten, C.D.; Mistry, N.; Klamut, H.; D’Aloisio, S.; MacLean, M.; Wainman, N.; et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of the human DNA methyltransferase antisense oligodeoxynucleotide MG98 given as a 21-day continuous infusion every 4 weeks. Investig. New Drugs 2003, 21, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klisovic, R.B.; Stock, W.; Cataland, S.; Klisovic, M.I.; Liu, S.; Blum, W.; Green, M.; Odenike, O.; Godley, L.; Burgt, J.V.; et al. A phase I biological study of MG98, an oligodeoxynucleotide antisense to DNA methyltransferase 1, in patients with high-risk myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 2444–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, R.; Vidal, L.; Griffin, M.; Lesley, M.; de Bono, J.; Coulthard, S.; Sludden, J.; Siu, L.L.; Chen, E.X.; Oza, A.M.; et al. Phase I study of MG98, an oligonucleotide antisense inhibitor of human DNA methyltransferase 1, given as a 7-day infusion in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3177–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, R.J.; Stephenson, J.; Hotte, S.; Nemunaitis, J.; Bélanger, K.; Reid, G.; Martell, R.E. MG98, a second-generation DNMT1 inhibitor, in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Investig. 2012, 30, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondelet, G.; Fleury, L.; Faux, C.; Masson, V.; Dubois, J.; Arimondo, P.B.; Willems, L.; Wouters, J. Inhibition studies of DNA methyltransferases by maleimide derivatives of RG108 as non-nucleoside inhibitors. Future Med. Chem. 2017, 9, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hou, J.; Cui, X.H.; Suo, L.N.; Lv, Y.W. RG108 induces the apoptosis of endometrial cancer Ishikawa cell lines by inhibiting the expression of DNMT3B and demethylation of HMLH1. Eur Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 5056–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, I.; Sousa, E.J.; Baptista, T.; Almeida, M.; Ramalho-Carvalho, J.; Palmeira, C.; Henrique, R.; Jerónimo, C. Anti-tumoral effect of the non-nucleoside DNMT inhibitor RG108 in human prostate cancer cells. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 1803–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Choi, S.; Medina-Franco, J.L. Molecular modeling studies of the novel inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases SGI-1027 and CBC12: Implications for the mechanism of inhibition of DNMTs. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, J.; Ghoshal, K.; Denny, W.A.; Gamage, S.A.; Brooke, D.G.; Phiasivongsa, P.; Redkar, S.; Jacob, S.T. A new class of quinoline-based DNA hypomethylating agents reactivates tumor suppressor genes by blocking DNA methyltransferase 1 activity and inducing its degradation. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 4277–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwergel, C.; Schnekenburger, M.; Sarno, F.; Battistelli, C.; Manara, M.C.; Stazi, G.; Mazzone, R.; Fioravanti, R.; Gros, C.; Ausseil, F.; et al. Identification of a novel quinoline-based DNA demethylating compound highly potent in cancer cells. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.Z.; Wang, Y.; Ai, N.; Hou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Lu, H.; Welsh, W.; Yang, C.S. Tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits DNA methyltransferase and reactivates methylation-silenced genes in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 7563–7570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nandakumar, V.; Vaid, M.; Katiyar, S.K. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate reactivates silenced tumor suppressor genes, Cip1/p21 and p16INK4a, by reducing DNA methylation and increasing histones acetylation in human skin cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2011, 32, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Shi, W.; Guo, H.; Long, W.; Wang, Y.; Qi, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y. The inhibitory effect of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate on breast cancer progression via reducing SCUBE2 methylation and DNMT activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilir, B.; Sharma, N.V.; Lee, J.; Hammarstrom, B.; Svindland, A.; Kucuk, O.; Moreno, C.S. Effects of genistein supplementation on genome-wide DNA methylation and gene expression in patients with localized prostate cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Bai, Q.; Zou, L.Y.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chang, H.; Yi, L.; Zhu, J.D.; Mi, M.T. Genistein inhibits DNA methylation and increases expression of tumor suppressor genes in human breast cancer cells. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2014, 53, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ren, J.; Tang, L. Genistein inhibits invasion and migration of colon cancer cells by recovering WIF1 expression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 7265–7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, A.; Balaguer, F.; Shen, Y.; Lozano, J.J.; Leung, H.C.; Boland, C.R.; Goel, A. Curcumin modulates DNA methylation in colorectal cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Luo, C. Identification of hypermethylation in hepatocyte cell adhesion molecule gene promoter region in bladder carcinoma. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 10, 1860–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hahn, N.M.; Bonney, P.L.; Dhawan, D.; Jones, D.R.; Balch, C.; Guo, Z.; Hartman-Frey, C.; Fang, F.; Parker, H.G.; Kwon, E.M.; et al. Subcutaneous 5-azacitidine treatment of naturally occurring canine urothelial carcinoma: A novel epigenetic approach to human urothelial carcinoma drug development. J. Urol. 2012, 187, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, S.; Hu, Q.; Krishnan, N.; Wang, D.; Smit, E.; Granger, V.; Rak, M.; Attwood, K.; Johnson, C.; Morrison, C.; et al. Decitabine, a DNA-demethylating agent, promotes differentiation via NOTCH1 signaling and alters immune-related pathways in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maraver, A.; Fernandez-Marcos, P.J.; Cash, T.P.; Mendez-Pertuz, M.; Dueñas, M.; Maietta, P.; Martinelli, P.; Muñoz-Martin, M.; Martínez-Fernández, M.; Cañamero, M.; et al. NOTCH pathway inactivation promotes bladder cancer progression. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, F.; Cao, Y.; Zu, X.; Chen, M.; Li, Z.; Qi, L. 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine enhances maspin expression and inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion of the bladder cancer T24 cell line. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2013, 28, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devanand, P.; Kim, S.I.; Choi, Y.W.; Sheen, S.S.; Yim, H.; Ryu, M.S.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, W.J.; Lim, I.K. Inhibition of bladder cancer invasion by Sp1-mediated BTG2 expression via inhibition of DNA methyltransferase 1. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 5581–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]