Peculiar Cat with Many Lives: PUMA in Viral Infections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search and Selection Criteria

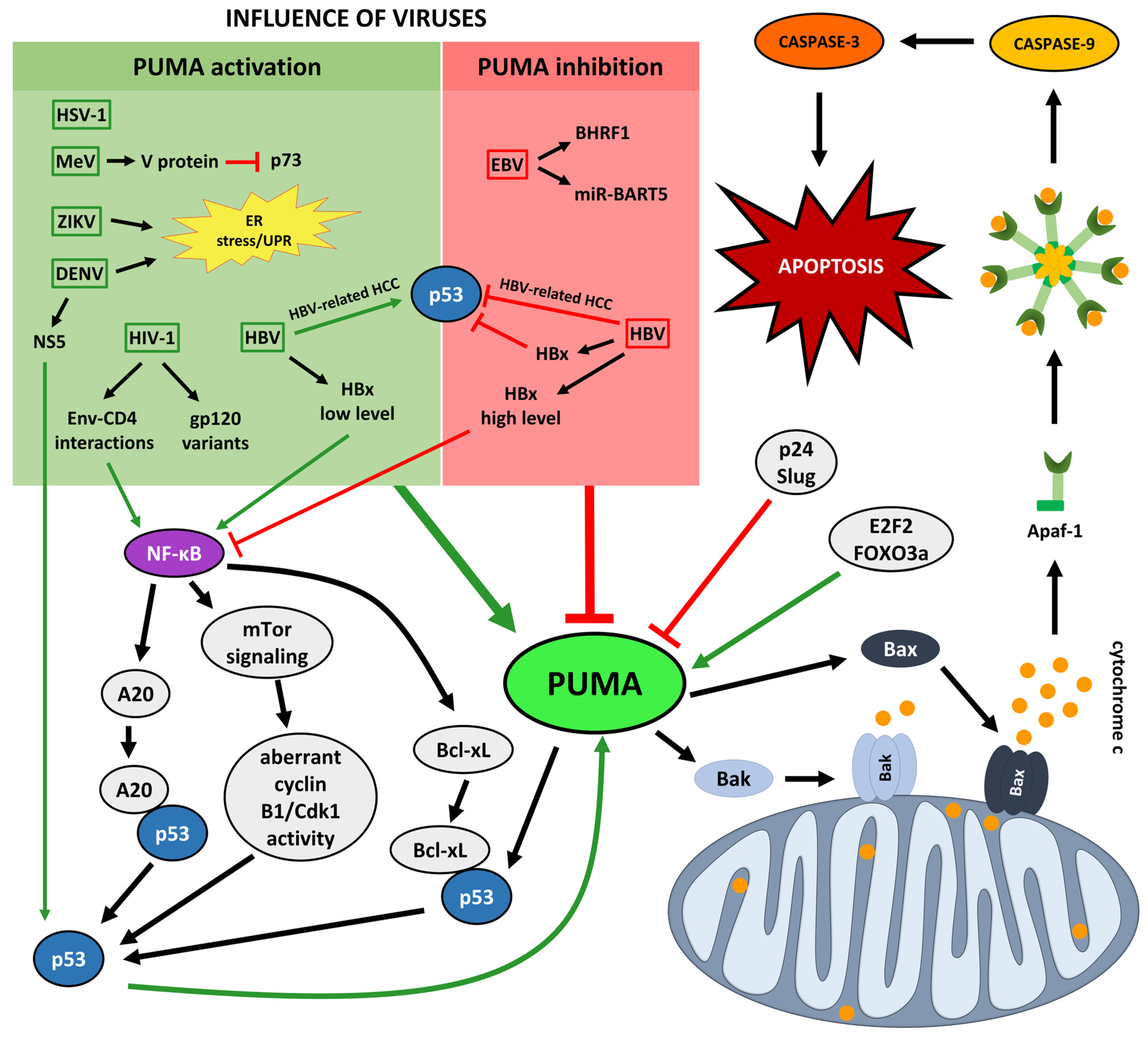

3. Molecular Biology of PUMA

4. PUMA in Viral Infections

4.1. PUMA in EBV Infections

4.2. PUMA in HSV-1 Infections

4.3. PUMA in HBV Infections

4.4. PUMA in HIV-1 Infections

4.5. PUMA in MeV Infections

4.6. PUMA in IAV Infections

4.7. PUMA in Flaviviral Infections

5. PUMA as a Prospective Therapeutic Target and Biomarker in Viral Infections

Therapeutic Translation: Current Developments

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3′ UTR | 3′ untranslated region |

| AIF | apoptosis-inducing factor |

| AIDS | acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| ARDS | acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| Apaf-1 | apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 |

| ATF6 | activating transcription factor 6 |

| Bak | Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer |

| Bad | Bcl-2-associated death promoter |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| Bcl-xL | B-cell lymphoma-extra large |

| BDTT | bile duct tumor thrombus |

| BH3 | Bcl-2 homology 3 domain |

| BHRF1 | BamHI fragment H rightward-facing protein |

| Bid | BH3 interacting domain death agonist |

| Bim | Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death |

| BL | Burkitt’s lymphoma |

| cccDNA | covalently closed circular DNA |

| Cdk1 | cyclin-dependent kinase 1 |

| cFLIP | cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein |

| CHOP | C/EBP homologous protein |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CTZ-8 | Component 8 |

| DBD | DNA-binding domain |

| DFS | disease-free survival |

| DISC | death-inducing signaling complex |

| DENV | Dengue virus |

| dsDNA | double-stranded DNA |

| EBERs | EBV-encoded small RNAs |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| Env | envelope glycoprotein complex (gp120/gp41) |

| eIF2α | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| FADD | Fas-associated death domain |

| FDMs | factor-dependent monocytes |

| FOXO3a | forkhead box O3 |

| GC | gastric carcinoma |

| GRP78 | glucose-regulated protein 78 |

| GST | glutathione S-transferase |

| HBc | hepatitis B core antigen |

| HBe | hepatitis B e antigen |

| HBs | hepatitis B surface protein |

| HBsAg | hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HBx | hepatitis B x protein |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HEK293 | human embryonic kidney 293 cells |

| HIV-1 | human immunodeficiency virus type 1 |

| hNePCs | human neural progenitor cells |

| HSE | herpes simplex encephalitis |

| HSV-1 | Herpes simplex virus type 1 |

| HUVECs | human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| IAV | influenza A virus |

| ICP | infected cell protein |

| iDNA | integrated viral DNA |

| IFN | interferon |

| IL | interleukin |

| IOD | integrated optical density |

| IκB | inhibitor of NF-κB |

| IRE1 | inositol-requiring enzyme 1 |

| LAT | latency-associated transcript |

| L-HBs | large HBs |

| MCP-1/CCL2 | monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 |

| MEFs | mouse embryonic fibroblasts |

| MeV | Measles virus |

| miR-BARTs | BamHI A rightward transcripts microRNAs |

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| MLS | mitochondrial localization signal |

| MOM | mitochondrial outer membrane |

| MOMP | mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization |

| mTOR | mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor κB |

| NKT cells | natural killer T cells |

| NK cells | natural killer cells |

| NPC | nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| NePCs | neural progenitor cells |

| NTCP | sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide |

| NS | non-structural protein |

| NSI | non-syncytium-inducing |

| ORFs | open reading frames |

| OS | overall survival |

| PARP | poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PCBM | peripheral blood mononuclear cell |

| PCD I | programmed cell death type I |

| PERK | PKR-like ER kinase |

| prM/M | premembrane/membrane protein |

| PUMA | p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis |

| PVTT | portal vein tumor thrombus |

| rcDNA | relaxed circular DNA |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RT-PCR | reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| RT-qPCR | quantitative RT PCR |

| shRNA | small hairpin RNA |

| SI | syncytium-inducing |

| ssRNA+ | single-stranded, positive-sense RNA |

| ssRNA− | single-stranded, negative-sense RNA |

| TAg | T antigen |

| Tc | cytotoxic T cells |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| TNFR-1 | TNF receptor 1 |

| TNM | tumor-node-metastasis |

| TRADD | TNF receptor-associated death domain |

| TUNEL | terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling |

| UPR | unfolded protein response |

| US | unique short kinase |

| XBP1 | X-box binding protein 1 |

| ZIKV | Zika virus |

References

- Szondy, Z.; Sarang, Z.; Kiss, B.; Garabuczi, É.; Köröskényi, K. Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms Triggered by Apoptotic Cells during Their Clearance. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbury, C.J.; Hickson, I.D. Cellular Responses to DNA Damage. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001, 41, 367–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoui, S.; Herold, M.J.; Strasser, A. Emerging Connectivity of Programmed Cell Death Pathways and Its Physiological Implications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 678–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, D.; Liu, G.; Zhang, M.; Pan, F. Caspase-Linked Programmed Cell Death in Prostate Cancer: From Apoptosis, Necroptosis, and Pyroptosis to PANoptosis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.G.; Oberst, A. The Antisocial Network: Cross Talk between Cell Death Programs in Host Defense. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Song, C.H.; Bae, S.J.; Ha, K.T.; Karki, R. Regulated Cell Death Pathways and Their Roles in Homeostasis, Infection, Inflammation, and Tumorigenesis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1632–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.N.; Kanneganti, T.D. PANoptosis in Viral Infection: The Missing Puzzle Piece in the Cell Death Field. J. Mol. Biol. 2022, 434, 167249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelut-Carneiro, N.; Fitzgerald, K.A. Apoptosis, Pyroptosis, and Necroptosis—Oh My! The Many Ways a Cell Can Die. J. Mol. Biol. 2022, 434, 167378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Lei, S. The Important Role of Cuproptosis and Cuproptosis-Related Genes in the Development of Thyroid Carcinoma Revealed by Transcriptomic Analysis and Experiments. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 91, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Gu, R.; Wang, M.; Sun, Z.; Wei, F. Comprehensive Analysis of the Prognostic Signature and Tumor Microenvironment Infiltration Characteristics of Cuproptosis-Related LncRNAs for Patients with Colon Adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1007918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xin, Y.; Wang, X.; Dong, Z. Characteristics of Two Different Immune Infiltrating Pyroptosis Subtypes in Ischemic Stroke. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Shao, Y.; Li, C. Different Types of Cell Death and Their Shift in Shaping Disease. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hong, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Wu, Y.; Hu, Y. Programmed Cell Death Tunes Tumor Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 847345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.F.R.; Wyllie, A.H.; Currie, A.R. Apoptosis: A Basic Biological Phenomenon with Wide-Ranging Implications in Tissue Kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 1972, 26, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkin-Smith, G.K.; Poon, I.K.H. Disassembly of the Dying: Mechanisms and Functions. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, M.; Ahmad, R.; Tantry, I.Q.; Ahmad, W.; Siddiqui, S.; Alam, M.; Abbas, K.; Moinuddin; Hassan, M.I.; Habib, S.; et al. Apoptosis: A Comprehensive Overview of Signaling Pathways, Morphological Changes, and Physiological Significance and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2024, 13, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyżewski, Z.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P.; Mielcarska, M.B.; Świtlik, W.; Niedzielska, A. Bid Protein: A Participant in the Apoptotic Network with Roles in Viral Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D.R. The Death Receptor Pathway of Apoptosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2022, 14, a041053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, H. Death Receptor-Ligand Systems in Cancer, Cell Death, and Inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a008698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devin, A.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Z.G. The Role of the Death-Domain Kinase RIP in Tumour-Necrosis-Factor-Induced Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kischkel, F.C.; Hellbardt, S.; Behrmann, I.; Germer, M.; Pawlita, M.; Krammer, P.H.; Peter, M.E. Cytotoxicity-Dependent APO-1 (Fas/CD95)-Associated Proteins Form a Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) with the Receptor. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 5579–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Choi, E.J.; Joe, C.O. Activation of Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) by pro-Apoptotic C-Terminal Fragment of RIP. Oncogene 2000, 19, 4491–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.K. Death Effecter Domain for the Assembly of Death-Inducing Signaling Complex. Apoptosis 2015, 20, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, J. Mechanisms of Cell Death. In Cell and Tissue Destruction; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, H.P.; Lo, Y.C.; Lin, S.C.; Wang, L.; Jin, K.Y.; Wu, H. The Death Domain Superfamily in Intracellular Signaling of Apoptosis and Inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 561–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantari, C.; Lafont, E.; Walczak, H. Death Receptor-Induced Apoptotic and Nonapoptotic Signaling. In Pathobiology of Human Disease: A Dynamic Encyclopedia of Disease Mechanisms; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A Review of Programmed Cell Death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, S.; Adams, J.M. The Bcl2 Family: Regulators of the Cellular Life-or-Death Switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, X.; Festjens, N.; Vande Walle, L.; Van Gurp, M.; Van Loo, G.; Vandenabeele, P. Toxic Proteins Released from Mitochondria in Cell Death. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2861–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Nijhawan, D.; Budihardjo, I.; Srinivasula, S.M.; Ahmad, M.; Alnemri, E.S.; Wang, X. Cytochrome c and DATP-Dependent Formation of Apaf-1/Caspase-9 Complex Initiates an Apoptotic Protease Cascade. Cell 1997, 91, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H.; Henzel, W.J.; Liu, X.; Lutschg, A.; Wang, X. Apaf-1, a Human Protein Homologous to C. Elegans CED-4, Participates in Cytochrome c-Dependent Activation of Caspase-3. Cell 1997, 90, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, A.I.M.; Reid Alderson, T.; Rennella, E.; Aramini, J.M.; Liu, Z.H.; Harkness, R.W.; Kay, L.E. Activation of Caspase-9 on the Apoptosome as Studied by Methyl-TROSY NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2310944120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousden, K.H. P53: Death Star. Cell 2000, 103, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieging, K.T.; Mello, S.S.; Attardi, L.D. Unravelling Mechanisms of P53-Mediated Tumour Suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakin, N.D.; Jackson, S.P. Regulation of P53 in Response to DNA Damage. Oncogene 1999, 18, 7644–7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Tao, Y. Regulating Tumor Suppressor Genes: Post-Translational Modifications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeHart, C.J.; Chahal, J.S.; Flint, S.J.; Perlman, D.H. Extensive Post-Translational Modification of Active and Inactivated Forms of Endogenous P53. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2014, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Zhu, W.G. Surf the Post-Translational Modification Network of P53 Regulation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 8, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, J.P.; Gu, W. SnapShot: P53 Posttranslational Modifications. Cell 2008, 133, 930.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Hua, S.; Min, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Wu, P.; Liang, H.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Xiang, S. P53 Positively Regulates the Proliferation of Hepatic Progenitor Cells Promoted by Laminin-521. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaddavalli, P.L.; Schumacher, B. The P53 Network: Cellular and Systemic DNA Damage Responses in Cancer and Aging. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, B.J.; Kelly, G.L.; Janic, A.; Herold, M.J.; Strasser, A. How Does P53 Induce Apoptosis and How Does This Relate to P53-Mediated Tumour Suppression? Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipuk, J.E.; Kuwana, T.; Bouchier-Hayes, L.; Droin, N.M.; Newmeyer, D.D.; Schuler, M.; Green, D.R. Direct Activation of Bax by P53 Mediates Mitochondrial Membrane Permeabilization and Apoptosis. Science 2004, 303, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, M.; Erster, S.; Zaika, A.; Petrenko, O.; Chittenden, T.; Pancoska, P.; Moll, U.M. P53 Has a Direct Apoptogenic Role at the Mitochondria. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, K.; Vousden, K.H. PUMA, a Novel Proapoptotic Gene, Is Induced by P53. Mol. Cell 2001, 7, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, L.; Hwang, P.M.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. PUMA Induces the Rapid Apoptosis of Colorectal Cancer Cells. Mol. Cell 2001, 7, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipuk, J.E.; Bouchier-Hayes, L.; Kuwana, T.; Newmeyer, D.D.; Green, D.R. PUMA Couples the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Proapoptotic Function of P53. Science 2005, 309, 1732–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D.R.; Kroemer, G. Cytoplasmic Functions of the Tumour Suppressor P53. Nature 2009, 458, 1127–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, J.R.; Parganas, E.; Lee, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.L.; Brennan, J.; MacLean, K.H.; Han, J.; Chittenden, T.; Ihle, J.N.; et al. Puma Is an Essential Mediator of P53-Dependent and -Independent Apoptotic Pathways. Cancer Cell 2003, 4, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Willis, S.N.; Wei, A.; Smith, B.J.; Fletcher, J.I.; Hinds, M.G.; Colman, P.M.; Day, C.L.; Adams, J.M.; Huang, D.C.S. Differential Targeting of Prosurvival Bcl-2 Proteins by Their BH3-Only Ligands Allows Complementary Apoptotic Function. Mol. Cell 2005, 17, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, B.J. Viruses and Apoptosis. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2001, 82, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainu, F.; Shiratsuchi, A.; Nakanishi, Y. Induction of Apoptosis and Subsequent Phagocytosis of Virus-Infected Cells As an Antiviral Mechanism. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.J. Interference of Apoptosis by Hepatitis B Virus. Viruses 2017, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, Y. Role of Bcl-2 Family Proteins in Apoptosis: Apoptosomes or Mitochondria? Genes Cells 1998, 3, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, B.B.; McFadden, G. Anti-Immunology: Evasion of the Host Immune System by Bacterial and Viral Pathogens. Cell 2006, 124, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, S.; Wan, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, R.; Li, G.; Cong, H. Zika Virus Infection Induced Apoptosis by Modulating the Recruitment and Activation of Pro-Apoptotic Protein Bax. J. Virol. 2021, 95, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Huang, C.; Shi, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, E.; Hu, R.; Li, G.; Yang, F.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, P.; et al. Investigation of the Crosstalk between GRP78/PERK/ATF-4 Signaling Pathway and Renal Apoptosis Induced by Nephropathogenic Infectious Bronchitis Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2022, 96, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.W.; Lee, H.N.; Jeong, M.S.; Park, S.Y.; Jang, S.B. Structural Basis of the P53 DNA Binding Domain and PUMA Complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 548, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B.; Zhang, L. PUMA Mediates the Apoptotic Response to P53 in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1931–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urist, M.; Tanaka, T.; Poyurovsky, M.V.; Prives, C. P73 Induction after DNA Damage Is Regulated by Checkpoint Kinases Chk1 and Chk2. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 3041–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melino, G.; Bernassola, F.; Ranalli, M.; Yee, K.; Zong, W.X.; Corazzari, M.; Knight, R.A.; Green, D.R.; Thompson, C.; Vousden, K.H. P73 Induces Apoptosis via PUMA Transactivation and Bax Mitochondrial Translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 8076–8083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Pellegrini, M.; Tsuchihara, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Hacker, G.; Erlacher, M.; Villunger, A.; Mak, T.W. FOXO3a-Dependent Regulation of Puma in Response to Cytokine/Growth Factor Withdrawal. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M.; O’Prey, J.; Tolkovsky, A.M.; Ryan, K.M. Phosphorylation of Puma Modulates Its Apoptotic Function by Regulating Protein Stability. Cell Death Dis. 2010, 1, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L. The Nuclear Function of P53 Is Required for PUMA-Mediated Apoptosis Induced by DNA Damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 4054–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershko, T.; Ginsberg, D. Up-Regulation of Bcl-2 Homology 3 (BH3)-Only Proteins by E2F1 Mediates Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 8627–8634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.S.; Heinrichs, S.; Xu, D.; Garrison, S.P.; Zambetti, G.P.; Adams, J.M.; Look, A.T. Slug Antagonizes P53-Mediated Apoptosis of Hematopoietic Progenitors by Repressing Puma. Cell 2005, 123, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, R.V.; Niazi, K.; Mollahan, P.; Mao, X.; Crippen, D.; Poksay, K.S.; Chen, S.; Bredesen, D.E. Coupling Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress to the Cell-Death Program: A Novel HSP90-Independent Role for the Small Chaperone Protein P23. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Tu, H.C.; Ren, D.; Takeuchi, O.; Jeffers, J.R.; Zambetti, G.P.; Hsieh, J.J.D.; Cheng, E.H.Y. Stepwise Activation of BAX and BAK by TBID, BIM, and PUMA Initiates Mitochondrial Apoptosis. Mol. Cell 2009, 36, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, S.N.; Fletcher, J.I.; Kaufmann, T.; Van Delft, M.F.; Chen, L.; Czabotar, P.E.; Ierino, H.; Lee, E.F.; Fairlie, W.D.; Bouillet, P.; et al. Apoptosis Initiated When BH3 Ligands Engage Multiple Bcl-2 Homologs, Not Bax or Bak. Science 2007, 315, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follis, A.V.; Chipuk, J.E.; Fisher, J.C.; Yun, M.K.; Grace, C.R.; Nourse, A.; Baran, K.; Ou, L.; Min, L.; White, S.W.; et al. PUMA Binding Induces Partial Unfolding within BCL-XL to Disrupt P53 Binding and Promote Apoptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Nong, S.; Gong, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Zhou, T.; Li, W. Hepatitis B Virus DNA Polymerase Displays an Anti-Apoptotic Effect by Interacting with Elongation Factor-1 Alpha-2 in Hepatoma Cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino-Merlo, F.; Klett, A.; Papaianni, E.; Drago, S.F.A.; Macchi, B.; Rincón, M.G.; Andreola, F.; Serafino, A.; Grelli, S.; Mastino, A.; et al. Caspase-8 Is Required for HSV-1-Induced Apoptosis and Promotes Effective Viral Particle Release via Autophagy Inhibition. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodamoradi, S.; Khodaei, F.; Mohammadian, T.; Ferdousi, A.; Rafiee, F. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis in Alzheimer’s Disease Associated with HSV-1 and CMV Coinfection. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Shi, D.; Tang, Y.D.; Zhang, L.; Hu, B.; Zheng, C.; Huang, L.; Weng, C. Pseudorabies Virus GM and Its Homologous Proteins in Herpesviruses Induce Mitochondria-Related Apoptosis Involved in Viral Pathogenicity. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, W.; Shen, J.; Li, M.; Gong, W. Targeting Proteasome Enhances Anticancer Activity of Oncolytic HSV-1 in Colorectal Cancer. Virology 2023, 578, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weniger, M.A.; Küppers, R. Molecular Biology of Hodgkin Lymphoma. Leukemia 2021, 35, 968–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghabeshi, S.; Najafi, A.; Zamani, B.; Soltani, M.; Arero, A.G.; Izadi, S.; Piroozmand, A. Evaluation of Molecular Apoptosis Signaling Pathways and Its Correlation with EBV Viral Load in SLE Patients Using Systems Biology Approach. Hum. Antibodies 2022, 30, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mund, R.; Whitehurst, C.B. Ubiquitin-Mediated Effects on Oncogenesis during EBV and KSHV Infection. Viruses 2024, 16, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Yang, T.; Li, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, H.; Jiang, J.; et al. EBV-Encoded MiRNAs BHRF1-1 and BART2-5p Aggravate Post- Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder via LZTS2-PI3K-AKT Axis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 214, 115676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraweera, C.D.; Hinds, M.G.; Kvansakul, M. Crystal Structures of Epstein-Barr Virus Bcl-2 Homolog BHRF1 Bound to Bid and Puma BH3 Motif Peptides. Viruses 2022, 14, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalilian, S.; Bastani, M.N. From Virus to Cancer: Epstein-Barr Virus MiRNA Connection in Burkitt’s Lymphoma. Infect. Agents Cancer 2024, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagi, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Hara, Y.; Sato, Y.; Kimura, H.; Murata, T. EBV Exploits RNA M6A Modification to Promote Cell Survival and Progeny Virus Production During Lytic Cycle. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 870816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremba, A.A.; Zaremba, P.Y.; Platonov, M.O. De Novo Designed EBAI as a Potential Inhibitor of the Viral Protein BHRF1. Research in Silico. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 3680–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da, D.; Qi, Y.; Dang, C.; Xue, L.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, H. EBV-MiR-BART5-3p Promotes the Proliferation of Burkitt Lymphoma Cells via Glycolytic Pathway. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Yadava, P.K. Measles Virus Phosphoprotein Inhibits Apoptosis and Enhances Clonogenic and Migratory Properties in HeLa Cells. J. Biosci. 2019, 44, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polonio, C.M.; Peron, J.P.S. Zikv Infection and Mirna Network in Pathogenesis and Immune Response. Viruses 2021, 13, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, D.; Li, Y.; Qin, L.; Wan, Q.; Hu, H.; Wu, M.; Feng, Y.; Schang, L.; Weiss, R.; et al. Erp57 Facilitates ZIKV-Induced DNA Damage via NS2B/NS3 Complex Formation. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2417864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Cheng, A.; Wang, M.; Yin, Z.; Jia, R. The Dual Regulation of Apoptosis by Flavivirus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 654494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, N.; Wu, S.; Xie, T.; Chen, Q.; Wu, J.; Zeng, S.; Zhu, L.; Bai, S.; Zha, H.; et al. C-FLIP Facilitates ZIKV Infection by Mediating Caspase-8/3-Dependent Apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, 1012408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, J.; El Safadi, D.; Lebeau, G.; Krejbich, M.; Chatelain, C.; Desprès, P.; Viranaïcken, W.; Krejbich-Trotot, P. Apoptosis during ZIKA Virus Infection: Too Soon or Too Late? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leowattana, W.; Leowattana, T. Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever and the Liver. World J. Hepatol. 2021, 13, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, K.; dos Santos, C.R.; Franco, E.C.S.; Martins Filho, A.J.; Casseb, S.M.M.; da Costa Vasconcelos, P.F. Exploring the Interplay between MiRNAs, Apoptosis and Viral Load, in Dengue Virus Infection. Virology 2024, 596, 110095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freppel, W.; Barragan Torres, V.A.; Uyar, O.; Anton, A.; Nouhi, Z.; Broquière, M.; Mazeaud, C.; Sow, A.A.; Léveillé, A.; Gilbert, C.; et al. Dengue Virus and Zika Virus Alter Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Contact Sites to Regulate Respiration and Apoptosis. iScience 2025, 28, 111599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucena-Neto, F.D.; Falcão, L.F.M.; da Silva Moraes, E.C.; David, J.P.F.; de Souza Vieira-Junior, A.; Silva, C.C.; de Sousa, J.R.; Duarte, M.I.S.; da Costa Vasconcelos, P.F.; Quaresma, J.A.S. Dengue Fever Ophthalmic Manifestations: A Review and Update. Rev. Med. Virol. 2023, 33, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabea Ekabe, C.; Asaba Clinton, N.; Agyei, E.K.; Kehbila, J. Role of Apoptosis in HIV Pathogenesis. Adv. Virol. 2022, 2022, 8148119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Cheung, P.H.H.; Wu, L. SAMHD1 Enhances HIV-1-Induced Apoptosis in Monocytic Cells via the Mitochondrial Pathway. mBio 2025, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chéret, A. Acute HIV-1 Infection: Paradigm and Singularity. Viruses 2025, 17, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorczyk, K.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Wyżewski, Z.; Struzik, J.; Niemiałtowski, M. Changes in the Mitochondrial Network during Ectromelia Virus Infection of Permissive L929 Cells. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2014, 61, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyżewski, Z.; Świtlik, W.; Mielcarska, M.B.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P. The Role of Bcl-XL Protein in Viral Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyżewski, Z.; Mielcarska, M.B.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P.; Myszka, A. Virus-Mediated Inhibition of Apoptosis in the Context of EBV-Associated Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimmons, L.; Boyce, A.J.; Wei, W.; Chang, C.; Croom-Carter, D.; Tierney, R.J.; Herold, M.J.; Bell, A.I.; Strasser, A.; Kelly, G.L.; et al. Coordinated Repression of BIM and PUMA by Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Genes Maintains the Survival of Burkitt Lymphoma Cells. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimmons, L.; Cartlidge, R.; Chang, C.; Sejic, N.; Galbraith, L.C.A.; Suraweera, C.D.; Croom-Carter, D.; Dewson, G.; Tierney, R.J.; Bell, A.I.; et al. EBV BCL-2 Homologue BHRF1 Drives Chemoresistance and Lymphomagenesis by Inhibiting Multiple Cellular pro-Apoptotic Proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 1554–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.-L.; Yao, D.-B.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, F.; Jia, C.-J.; Xu, Y.-Q.; Dai, C.-L. Prognostic Value of PUMA Expression in Patients with HBV-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahn, C.H.; Jeong, E.G.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, M.S.; Yoo, N.J.; Lee, S.H. Expressional and Mutational Analysis of Pro-Apoptotic Bcl-2 Member PUMA in Hepatocellular Carcinomas. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2008, 53, 1395–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Meng, D.; Wei, T.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, M. Apoptosis and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Response of Mast Cells Induced by Influenza A Viruses. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonomy Browser. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?id=10376 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- He, H.P.; Luo, M.; Cao, Y.L.; Lin, Y.X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Ou, J.Y.; Yu, B.; Chen, X.; Xu, M.; et al. Structure of Epstein-Barr Virus Tegument Protein Complex BBRF2-BSRF1 Reveals Its Potential Role in Viral Envelopment. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, E.Y.W.; Siu, K.L.; Kok, K.H.; Lung, R.W.M.; Tsang, C.M.; To, K.F.; Kwong, D.L.W.; Tsao, S.W.; Jin, D.Y. An Epstein-Barr Virus–Encoded MicroRNA Targets PUMA to Promote Host Cell Survival. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonomy Browser (Human Alphaherpesvirus 1). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?command=show&mode=node&id=10298&lvl= (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Zhu, S.; Viejo-Borbolla, A. Pathogenesis and Virulence of Herpes Simplex Virus. Virulence 2021, 12, 2670–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, C.; Harfouche, M.; Welton, N.J.; Turner, K.M.E.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Gottlieb, S.L.; Looker, K.J. Herpes Simplex Virus: Global Infection Prevalence and Incidence Estimates, 2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D.; Han, L.; Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Qian, S.; Feng, Z.; Yu, L. An Updated Review of HSV-1 Infection-Associated Diseases and Treatment, Vaccine Development, and Vector Therapy Application. Virulence 2024, 15, 2425744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.; Reuven, N.; Mohni, K.N.; Schumacher, A.J.; Weller, S.K. Structure of the Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Genome: Manipulation of Nicks and Gaps Can Abrogate Infectivity and Alter the Cellular DNA Damage Response. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 10146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaianni, E.; El Maadidi, S.; Schejtman, A.; Neumann, S.; Maurer, U.; Marino-Merlo, F.; Mastino, A.; Borner, C. Phylogenetically Distant Viruses Use the Same BH3-Only Protein Puma to Trigger Bax/Bak-Dependent Apoptosis of Infected Mouse and Human Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastino, A.; Sciortino, M.T.; Medici, M.A.; Perri, D.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Grelli, S.; Amici, C.; Pernice, A.; Guglielmino, S. Herpes Simplex Virus 2 Causes Apoptotic Infection in Monocytoid Cells. Cell Death Differ. 1997, 4, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Watanabe, M.; Kamiya, H.; Sakurai, M. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Induces Apoptosis in Peripheral Blood T Lymphocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 175, 1220–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosnjak, L.; Miranda-Saksena, M.; Koelle, D.M.; Boadle, R.A.; Jones, C.A.; Cunningham, A.L. Herpes Simplex Virus Infection of Human Dendritic Cells Induces Apoptosis and Allows Cross-Presentation via Uninfected Dendritic Cells. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 2220–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kather, A.; Raftery, M.J.; Devi-Rao, G.; Lippmann, J.; Giese, T.; Sandri-Goldin, R.M.; Schönrich, G. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV-1)-Induced Apoptosis in Human Dendritic Cells as a Result of Downregulation of Cellular FLICE-Inhibitory Protein and Reduced Expression of HSV-1 Antiapoptotic Latency-Associated Transcript Sequences. J. Virol. 2009, 84, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.; Gyure, K.A.; Pereira, E.F.R.; Aurelian, L. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1-Induced Encephalitis Has an Apoptotic Component Associated with Activation of c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase. J. Neurovirol. 2003, 9, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.F.; Belz, G.T.; Strasser, A. BH3-Only Protein Puma Contributes to Death of Antigen-Specific T Cells during Shutdown of an Immune Response to Acute Viral Infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3035–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, T.; Xue, L.; Liang, H. Pathogenesis, Prevention, and Therapeutic Advances in Hepatitis B, C, and D. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M.; Lok, J.; Wand, N.; Magri, A.; Tsukuda, S.; Wu, Y.; Ng, E.; Jennings, D.; Elshenawy, B.; Balfe, P.; et al. Episomal and Integrated Hepatitis B Transcriptome Mapping Uncovers Heterogeneity with the Potential for Drug-Resistance. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringelhan, M.; Schuehle, S.; van de Klundert, M.; Kotsiliti, E.; Plissonnier, M.L.; Faure-Dupuy, S.; Riedl, T.; Lange, S.; Wisskirchen, K.; Thiele, F.; et al. HBV-Related HCC Development in Mice Is STAT3 Dependent and Indicates an Oncogenic Effect of HBx. JHEP Rep. 2024, 6, 101128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Mao, B.; Hu, J.; Shi, M.; Wang, S.; Rehman, A.U.; Li, X. Tumor-Associated Macrophages and CD8+ T Cells: Dual Players in the Pathogenesis of HBV-Related HCC. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1472430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cao, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, S.; Liu, Y.; Liang, R.; Zhu, R.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Sun, Y. Enhanced Interactions within Microenvironment Accelerates Dismal Prognosis in HBV-Related HCC after TACE. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8, e0548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, M.; Xie, S.; Liu, Y. Clinical Features of HBV-Related HCC in Long-Term NAs-Treated Versus Untreated Patients. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, 70717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, C.J.; Chen, H.T.; Huang, Y.H.; Pan, M.H.; Lee, M.H.; Viard, M.; Hildesheim, A.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Carrington, M.; et al. HLA-DQB1*03:01 and Risk of Hepatitis B Virus-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2025, 83, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Gao, Y.; Fu, J.; Xie, R.; Zhu, Z.; Hong, Z.; Meng, L.; Du, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.S.; et al. Epigenetic Regulation of HBV-Specific Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells in HBV-Related HCC. Hepatology 2023, 78, 943–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Yu, J.; Tao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lau, W.Y.; Zhou, W.; Huang, G. Tenofovir vs Entecavir Among Patients with HBV-Related HCC After Resection. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, 40353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Ni, X.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, C.; Qi, X.; Huo, H.; Lou, X.; et al. Serum GGT/ALT Ratio Predicts Vascular Invasion in HBV-Related HCC. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Xia, Y.; Wang, S. IL35 Modulates HBV-Related HCC Progression via IL6-STAT3 Signaling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Nah, B.K.Y.; Leo, J.; Koh, J.H.; Huang, D.Q. Optimizing Care of HBV Infection and HBV-Related HCC. Clin. Liver Dis. 2024, 23, e0169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.; Lei, Z.; Tu, B.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Huang, F. NEDD4 Induces K48-Linked Degradative Ubiquitination of Hepatitis B Virus X Protein and Inhibits HBV-Associated HCC Progression. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 625169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannuzzi, A.T.; Sari, G.; Arslan-Eseryel, S.; Zeybel, M.; Yilmaz, Y.; Dayangac, M.; Yigit, B.; Arga, K.Y.; Boonstra, A.; Eren, F.; et al. HBV Infection Drives PSMB5-Dependent Proteasomal Activation in Humanized Mice and HBV-Associated HCC. Viruses 2025, 17, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataman, E.; Harputluoglu, M.; Carr, B.I.; Gozukara, H.; Ince, V.; Yilmaz, S. HBV Viral Load and Tumor and Non-Tumor Factors in Patients with HBV-Associated HCC. Hepatol. Forum 2024, 5, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, B.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. Increased BST-2 Expression by HBV Infection Promotes HBV-Associated HCC Tumorigenesis. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 12, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Liu, L.; Sun, C. The Dynamic Role of NK Cells in Liver Cancers: Role in HCC and HBV Associated HCC and Its Therapeutic Implications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 887186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose-Abrego, A.; Roman, S.; Laguna-Meraz, S.; Panduro, A. Host and HBV Interactions and Their Potential Impact on Clinical Outcomes. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clippinger, A.J.; Gearhart, T.L.; Bouchard, M.J. Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Modulates Apoptosis in Primary Rat Hepatocytes by Regulating Both NF-KappaB and the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 4718–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, L. PUMA, a Potent Killer with or without P53. Oncogene 2008, 27, S71–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z. Ubiquitin Ligase A20 Regulates P53 Protein in Human Colon Epithelial Cells. J. Biomed. Sci. 2013, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonomy Browser (Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?command=show&mode=node&id=11676&lvl= (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Belawati, Y.R.; Febrinasari, R.P.; Widyaningsih, V.; Probandari, A. From Health to AIDS: Exploring the Quality of Life among Men Who Have Sex with Men along the HIV Spectrum in a Mid-Sized City in Indonesia. AIDS Care 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orser, L.; O’Byrne, P.; Holmes, D. AIDS Cases in Ottawa: A Review of Simultaneous HIV and AIDS Diagnoses. Public Health Nurs. 2022, 39, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraheni, R.; Murti, B.; Irawanto, M.E.; Sulaiman, E.S.; Pamungkasari, E.P. The Social Capital Effect on HIV/AIDS Preventive Efforts: A Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Life 2022, 15, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global HIV & AIDS Statistics—Fact Sheet|UNAIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Leung, K.; Kim, J.O.; Ganesh, L.; Kabat, J.; Schwartz, O.; Nabel, G.J. HIV-1 Assembly: Viral Glycoproteins Segregate Quantally to Lipid Rafts That Associate Individually with HIV-1 Capsids and Virions. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 3, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levintov, L.; Vashisth, H. Structural and Computational Studies of HIV-1 RNA. RNA Biol. 2023, 21, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundquist, W.I.; Kräusslich, H.G. HIV-1 Assembly, Budding, and Maturation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badley, A.D.; Pilon, A.A.; Landay, A.; Lynch, D.H. Mechanisms of HIV-Associated Lymphocyte Apoptosis. Blood 2000, 96, 2951–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Février, M.; Dorgham, K.; Rebollo, A. CD4+ T Cell Depletion in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection: Role of Apoptosis. Viruses 2011, 3, 586–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gougeon, M.L. Apoptosis as an HIV Strategy to Escape Immune Attack. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Hingrat, Q.; Sereti, I.; Landay, A.L.; Pandrea, I.; Apetrei, C. The Hitchhiker Guide to CD4+ T-Cell Depletion in Lentiviral Infection. A Critical Review of the Dynamics of the CD4+ T Cells in SIV and HIV Infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 695674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoye, A.A.; Picker, L.J. CD4(+) T-Cell Depletion in HIV Infection: Mechanisms of Immunological Failure. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 254, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, K.V.; Karthigeyan, K.P.; Tripathi, S.P.; Hanna, L.E. Pathophysiology of CD4+ T-Cell Depletion in HIV-1 and HIV-2 Infections. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.; Barretina, J.; Ferri, K.F.; Jacotot, E.; Gutiérrez, A.; Armand-Ugón, M.; Cabrera, C.; Kroemer, G.; Clotet, B.; Esté, J.A. Cell-Surface-Expressed HIV-1 Envelope Induces the Death of CD4 T Cells during GP41-Mediated Hemifusion-like Events. Virology 2003, 305, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, K.F.; Jacotot, E.; Blanco, J.; Esté, J.A.; Zamzami, N.; Susin, S.A.; Xie, Z.; Brothers, G.; Reed, J.C.; Penninger, J.M.; et al. Apoptosis Control in Syncytia Induced by the HIV Type 1-Envelope Glycoprotein Complex: Role of Mitochondria and Caspases. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siliciano, R.F.; Greene, W.C. HIV Latency. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2011, 1, A007096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Rodriguez, A.L.; Reuter, M.A.; McDonald, D. Dendritic Cells Enhance HIV Infection of Memory CD4(+) T Cells in Human Lymphoid Tissues. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2016, 32, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bon, I.; Clò, A.; Borderi, M.; Colangeli, V.; Calza, L.; Morini, S.; Miserocchi, A.; Cricca, M.; Gibellini, D.; Re, M.C. Prevalence of R5 Strains in Multi-Treated HIV Subjects and Impact of New Regimens Including Maraviroc in a Selected Group of Patients with CCR5-Tropic HIV-1 Infection. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, e875–e882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, M.B.; Leduc, R.; Kostman, J.R.; Labriola, A.M.; Lie, Y.; Weidler, J.; Coakley, E.; Bates, M.; Luskin-Hawk, R. Relationship between HIV Coreceptor Tropism and Disease Progression in Persons with Untreated Chronic HIV Infection. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009, 50, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuitemaker, H.; Koot, M.; Kootstra, N.A.; Dercksen, M.W.; de Goede, R.E.; van Steenwijk, R.P.; Lange, J.M.; Schattenkerk, J.K.; Miedema, F.; Tersmette, M. Biological Phenotype of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Clones at Different Stages of Infection: Progression of Disease Is Associated with a Shift from Monocytotropic to T-Cell-Tropic Virus Population. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van ’t Wout, A.B.; Blaak, H.; Ran, L.J.; Brouwer, M.; Kuiken, C.; Schuitemaker, H. Evolution of Syncytium-Inducing and Non-Syncytium-Inducing Biological Virus Clones in Relation to Replication Kinetics during the Course of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Infection. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 5099–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Haughey, N.J.; Nath, A. Cell Death in HIV Dementia. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shieh, J.T.C.; Martín, J.; Baltuch, G.; Malim, M.H.; González-Scarano, F. Determinants of Syncytium Formation in Microglia by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1: Role of the V1/V2 Domains. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senftleben, U.; Schlottmann, S.; Buback, F.; Stahl, B.; Meierhenrich, R.; Walther, P.; Georgieff, M. Prolonged Classical NF-KappaB Activation Prevents Autophagy upon E. Coli Stimulation in Vitro: A Potential Resolving Mechanism of Inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2008, 2008, 725854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzella, D.; Pescatore, A.; Capece, D.; Vecchiotti, D.; Ursini, M.V.; Franzoso, G.; Alesse, E.; Zazzeroni, F. Life, Death, and Autophagy in Cancer: NF-ΚB Turns up Everywhere. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahr, B.; Robert-Hebmann, V.; Devaux, C.; Biard-Piechaczyk, M. Apoptosis of Uninfected Cells Induced by HIV Envelope Glycoproteins. Retrovirology 2004, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, H.S.; Pauza, C.D.; Bukrinsky, M.; Zhao, R.Y. Roles of HIV-1 Auxiliary Proteins in Viral Pathogenesis and Host-Pathogen Interactions. Cell Res. 2005, 15, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardacci, R.; Perfettini, J.L.; Grieco, L.; Thieffry, D.; Kroemer, G.; Piacentini, M. Syncytial Apoptosis Signaling Network Induced by the HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein Complex: An Overview. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfettini, J.L.; Roumier, T.; Castedo, M.; Larochette, N.; Boya, P.; Raynal, B.; Lazar, V.; Ciccosanti, F.; Nardacci, R.; Penninger, J.; et al. NF-KappaB and P53 Are the Dominant Apoptosis-Inducing Transcription Factors Elicited by the HIV-1 Envelope. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 199, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonomy Browser. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?searchTerm=measles+virus&searchMode=complete+name&lock=1&unlock=1&command=search (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Misin, A.; Antonello, R.M.; Di Bella, S.; Campisciano, G.; Zanotta, N.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Comar, M.; Luzzati, R. Measles: An Overview of a Re-Emerging Disease in Children and Immunocompromised Patients. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, G.; Liu, B. Structure of the Measles Virus Ternary Polymerase Complex. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, H.Y. Measles Virus. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2015, 11, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guryanov, S.G.; Liljeroos, L.; Kasaragod, P.; Kajander, T.; Butcher, S.J. Crystal Structure of the Measles Virus Nucleoprotein Core in Complex with an N-Terminal Region of Phosphoprotein. J. Virol. 2015, 90, 2849–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, C.D.; Palosaari, H.; Parisien, J.-P.; Devaux, P.; Cattaneo, R.; Ouchi, T.; Horvath, C.M. Measles Virus V Protein Inhibits P53 Family Member P73. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansley, E.K.; Parks, G.D. Naturally Occurring Substitutions in the P/V Gene Convert the Noncytopathic Paramyxovirus Simian Virus 5 into a Virus That Induces Alpha/Beta Interferon Synthesis and Cell Death. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 10109–10121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansley, E.K.; Grayson, J.M.; Parks, G.D. Apoptosis Induction and Interferon Signaling but Not IFN-β Promoter Induction by an SV5 P/V Mutant Are Rescued by Coinfection with Wild-Type SV5. Virology 2003, 316, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Taxonomy Browser (Influenza A Virus). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?command=show&mode=node&id=11320&lvl= (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Reddy, M.K.; Ca, J.; Kandi, V.; Murthy, P.M.; Harikrishna, G.V.; Reddy, S.; Gr, M.; Sam, K.; Challa, S.T. Exploring the Correlation Between Influenza A Virus (H3N2) Infections and Neurological Manifestations: A Scoping Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e36936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, K.E.; Baer, L.A.; Karekar, P.; Nelson, A.M.; Stanford, K.I.; Doolittle, L.M.; Rosas, L.E.; Hickman-Davis, J.M.; Singh, H.; Davis, I.C. Metabolic Shifts Modulate Lung Injury Caused by Infection with H1N1 Influenza A Virus. Virology 2021, 559, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beans, C. Researchers Getting Closer to a “Universal” Flu Vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2123477119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fougerolles, T.R.; Baïssas, T.; Perquier, G.; Vitoux, O.; Crépey, P.; Bartelt-Hofer, J.; Bricout, H.; Petitjean, A. Public Health and Economic Benefits of Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in Risk Groups in France, Italy, Spain and the UK: State of Play and Perspectives. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grohskopf, L.A.; Ferdinands, J.M.; Blanton, L.H.; Broder, K.R.; Loehr, J. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-United States, 2024–2025 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2024, 73, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsoulis-Dimitriou, K.; Kotrba, J.; Voss, M.; Dudeck, J.; Dudeck, A. Mast Cell Functions Linking Innate Sensing to Adaptive Immunity. Cells 2020, 9, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D. Mast Cell Proteases and Metastasis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2025, 266, 155801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiakshin, D.; Morozov, S.; Dlin, V.; Kostin, A.; Volodkin, A.; Ignatyuk, M.; Kuzovleva, G.; Baiko, S.; Chekmareva, I.; Chesnokova, S.; et al. Renal Mast Cell-Specific Proteases in the Pathogenesis of Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2024, 72, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, F.; Mogren, S.; Tutzauer, J.; Andersson, C.K. Mast Cell Proteases Tryptase and Chymase Induce Migratory and Morphological Alterations in Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughey, G.H. Update on Mast Cell Proteases as Drug Targets. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2023, 43, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, L.; Akula, S.; Fu, Z.; Wernersson, S. Mast Cell and Basophil Granule Proteases—In Vivo Targets and Function. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 918305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willows, S.D.; Vliagoftis, H.; Sim, V.L.; Kulka, M. PrP Is Cleaved from the Surface of Mast Cells by ADAM10 and Proteases Released during Degranulation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2024, 116, 838–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-N.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Peng, X.-F.; Ge, H.-H.; Wang, G.; Ding, H.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Zhang, J.-T.; et al. Mast Cell-Derived Proteases Induce Endothelial Permeability and Vascular Damage in Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0129422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramu, S.; Akbarshahi, H.; Mogren, S.; Berlin, F.; Cerps, S.; Menzel, M.; Hvidtfeldt, M.; Porsbjerg, C.; Uller, L.; Andersson, C.K. Direct Effects of Mast Cell Proteases, Tryptase and Chymase, on Bronchial Epithelial Integrity Proteins and Anti-Viral Responses. BMC Immunol. 2021, 22, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitte, J.; Vibhushan, S.; Bratti, M.; Montero-Hernandez, J.E.; Blank, U. Allergy, Anaphylaxis, and Nonallergic Hypersensitivity: IgE, Mast Cells, and Beyond. Med. Princ. Pract. 2022, 31, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, M.P.B.; Blixt, F.W.; Peesh, P.; Khan, R.; Korf, J.; Lee, J.; Jagadeesan, G.; Andersohn, A.; Das, T.K.; Tan, C.; et al. Stabilizing Histamine Release in Gut Mast Cells Mitigates Peripheral and Central Inflammation after Stroke. J. Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkhir, P.; Giménez-Arnau, A.M.; Kulthanan, K.; Peter, J.; Metz, M.; Maurer, M. Urticaria. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakavas, S.; Karayiannis, D.; Mastora, Z. The Complex Interplay between Immunonutrition, Mast Cells, and Histamine Signaling in COVID-19. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Younis, S.; Shi, H.; Hu, S.; Zia, A.; Wong, H.H.; Elliott, E.E.; Chang, T.; Bloom, M.S.; Zhang, W.; et al. RNA-Seq Characterization of Histamine-Releasing Mast Cells as Potential Therapeutic Target of Osteoarthritis. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 244, 109117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.; Baiocchi, L.; Kennedy, L.; Sato, K.; Meadows, V.; Meng, F.; Huang, C.K.; Kundu, D.; Zhou, T.; Chen, L.; et al. The Interplay between Mast Cells, Pineal Gland, and Circadian Rhythm: Links between Histamine, Melatonin, and Inflammatory Mediators. J. Pineal Res. 2021, 70, 12699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asero, R. Mechanisms of Histamine Release from Mast Cells beyond the High Affinity IgE Receptor in Severe Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 265, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilfillan, A.M.; Austin, S.J.; Metcalfe, D.D. Mast Cell Biology: Introduction and Overview. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011, 716, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Han, D.; Zhang, G.; Cao, S.; Xie, J.; Xue, J.; Li, Y.; Meng, D.; Fan, X.; et al. Mast Cell-Induced Lung Injury in Mice Infected with H5N1 Influenza Virus. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3347–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy-Schafer, A.R.; Paust, S. Divergent Mast Cell Responses Modulate Antiviral Immunity During Influenza Virus Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 580679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, E.A.; Ali, T.; Sajjad, N.; Kumar, R.; Bron, P. Insights into the Structure, Functional Perspective, and Pathogenesis of ZIKV: An Updated Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. Recent Advances in the Study of Zika Virus Structure, Drug Targets, and Inhibitors. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1418516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thepparit, C.; Khakpoor, A.; Khongwichit, S.; Wikan, N.; Fongsaran, C.; Chingsuwanrote, P.; Panraksa, P.; Smith, D.R. Dengue 2 Infection of HepG2 Liver Cells Results in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Induction of Multiple Pathways of Cell Death. BMC Res. Notes 2013, 6, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Jiang, H.; Peng, H.; Zeng, W.; Zhong, Y.; He, M.; Xie, L.; Chen, J.; Guo, D.; Wu, J.; et al. Non-Structural Protein 5 of Zika Virus Interacts with P53 in Human Neural Progenitor Cells and Induces P53-Mediated Apoptosis. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, C.; Delaney, A.; Shukla, D.; Hahka, T.; Anderson-Berry, A.; Natarajan, S.K. Palmitoleate Protects against Zika Virus Infection-Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Apoptosis in Neurons. bioRxiv 2025. bioRxiv:2025.01.22.634157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Liu, J.; Zhou, N.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, H. CLZ-8, a Potent Small-Molecular Compound, Protects Radiation-Induced Damages Both in Vitro and in Vivo. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 61, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castedo, M.; Ferri, K.E.; Blanco, J.; Roumier, T.; Larochette, N.; Barretina, J.; Amendola, A.; Nardacci, R.; Métivier, D.; Este, J.A.; et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 Envelope Glycoprotein Complex-Induced Apoptosis Involves Mammalian Target of Rapamycin/FKBP12-Rapamycin-Associated Protein-Mediated P53 Phosphorylation. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 194, 1097–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Virus | Viral Factor(s) | Mechanism | Apoptotic Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| EBV | miR-BART5 | Direct targeting of PUMA mRNA (3′ UTR binding) | Anti-apoptotic |

| BHRF1 | Direct sequestration of PUMA (protein binding) | Anti-apoptotic | |

| HSV-1 | Not clearly identified | Indirect promotion of PUMA protein accumulation independent of p53/p73/NF-κB | Pro-apoptotic |

| HBV | HBx | Direct binding and inactivation of p53, leading to reduced PUMA transcription | Anti-apoptotic |

| NF-κB signaling activation, leading to inhibition of p53-dependent PUMA induction (low HBx levels) | Anti-apoptotic | ||

| NF-κB activity suppression, leading to enhancement of p53-dependent PUMA induction (high HBx levels) | Pro-apoptotic | ||

| HIV-1 | Env | NF-κB-dependent p53-mediated stimulation of PUMA transcription | Pro-apoptotic |

| p53-independent PUMA induction | Pro-apoptotic | ||

| MeV | V protein | Inhibition of p73-mediated PUMA transcription | Anti-apoptotic |

| ZIKV | Not defined | ER stress/UPR activation | Pro-apoptotic |

| DENV | Not defined | ER stress/UPR activation | Pro-apoptotic |

| NS5 | Stabilization of p53 and p53-dependent PUMA induction | Pro-apoptotic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wyżewski, Z.; Stępkowska, J.; Pruchniak, P.; Niedzielska, A.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P.; Mielcarska, M.B. Peculiar Cat with Many Lives: PUMA in Viral Infections. Cells 2026, 15, 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030278

Wyżewski Z, Stępkowska J, Pruchniak P, Niedzielska A, Gregorczyk-Zboroch KP, Mielcarska MB. Peculiar Cat with Many Lives: PUMA in Viral Infections. Cells. 2026; 15(3):278. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030278

Chicago/Turabian StyleWyżewski, Zbigniew, Justyna Stępkowska, Pola Pruchniak, Adrianna Niedzielska, Karolina Paulina Gregorczyk-Zboroch, and Matylda Barbara Mielcarska. 2026. "Peculiar Cat with Many Lives: PUMA in Viral Infections" Cells 15, no. 3: 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030278

APA StyleWyżewski, Z., Stępkowska, J., Pruchniak, P., Niedzielska, A., Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K. P., & Mielcarska, M. B. (2026). Peculiar Cat with Many Lives: PUMA in Viral Infections. Cells, 15(3), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030278