Exercise Protects Skeletal Muscle Fibers from Age-Related Dysfunctional Remodeling of Mitochondrial Network and Sarcotubular System

Highlights

- Studying the effect of inactivity vs. exercise on ultrastructure of skeletal muscle fibers has given us the opportunity to discover that the correct position of mitochondria is lost in sedentary aging and inactivity, but is maintained by regular exercise.

- Function of SOCE (a mechanism that allows fibers to use external Ca2+ and limit muscle fatigue) also depends on regular muscle activity.

- The maintenance of the internal architecture of muscle fibers is crucial for their capability to function properly.

- The proper position of mitochondria in proximity of sites of Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry may be crucial for the metabolic efficiency of muscle, and thus of the entire organism.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Organization of Organelles and Intracellular Membranes Involved in Aerobic ATP Production and Ca2+ Handling

2.1. Organelles Dedicated to Aerobic ATP Production: Mitochondria

2.2. The Organelles Dedicated to Ca2+ Handling: Triads and Ca2+ Entry Units

- Excitation-coupled Ca2+ entry (ECCE), a pathway first described in the early 2000s, which was later associated with the opening of the alpha-1 subunit of the DHPR—the voltage sensor in mechanical EC coupling that also forms an L-type Ca2+ channel that (in skeletal fibers) is slow and has little ion conductance [135,136]. As ECCE is altered in malignant hyperthermia susceptibility (MHS), it was argued that it may contribute to the dysfunctional Ca2+ signaling found in muscle fibers of MHS patients [137].

- Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), a pathway that allows extracellular Ca2+ to enter the cytosol and refill SR stores during repetitive muscle activity [22,23,27,28,138]. SOCE is activated by a phenomenon known as SR depletion, i.e., a reduction in the total amount of Ca2+ stored in the SR caused by the loss of intracellular Ca2+ across the sarcolemma during prolonged muscle activity [139,140,141,142]. SOCE was first characterized in non-excitable cells [22,23], but was detected in skeletal muscle myotubes and fibers only several years later [24,25,26]. Initially, the molecular players of SOCE remained elusive for years after the first identification of the mechanism, until, in 2005–2007, the two main proteins involved were discovered in patients affected by a severe immunodeficiency [143,144,145,146,147]: (a) STIM1 (stromal-interacting molecule-1), an ER/SR protein that acts as Ca2+ sensors due to the presence of an intraluminal N-terminal EF-hand domain; (b) ORAI1, a Ca2+ release-activated channel (CRAC) of the plasma membrane. Also, calsequestrin-1 (CASQ1), a protein involved in EC coupling with the dual role of being the main SR buffer that accumulates Ca2+ in proximity to the sites of release and also a direct modulator of RYR1 [118,119,132], has been proposed to modulate SOCE in skeletal muscle [148,149,150].

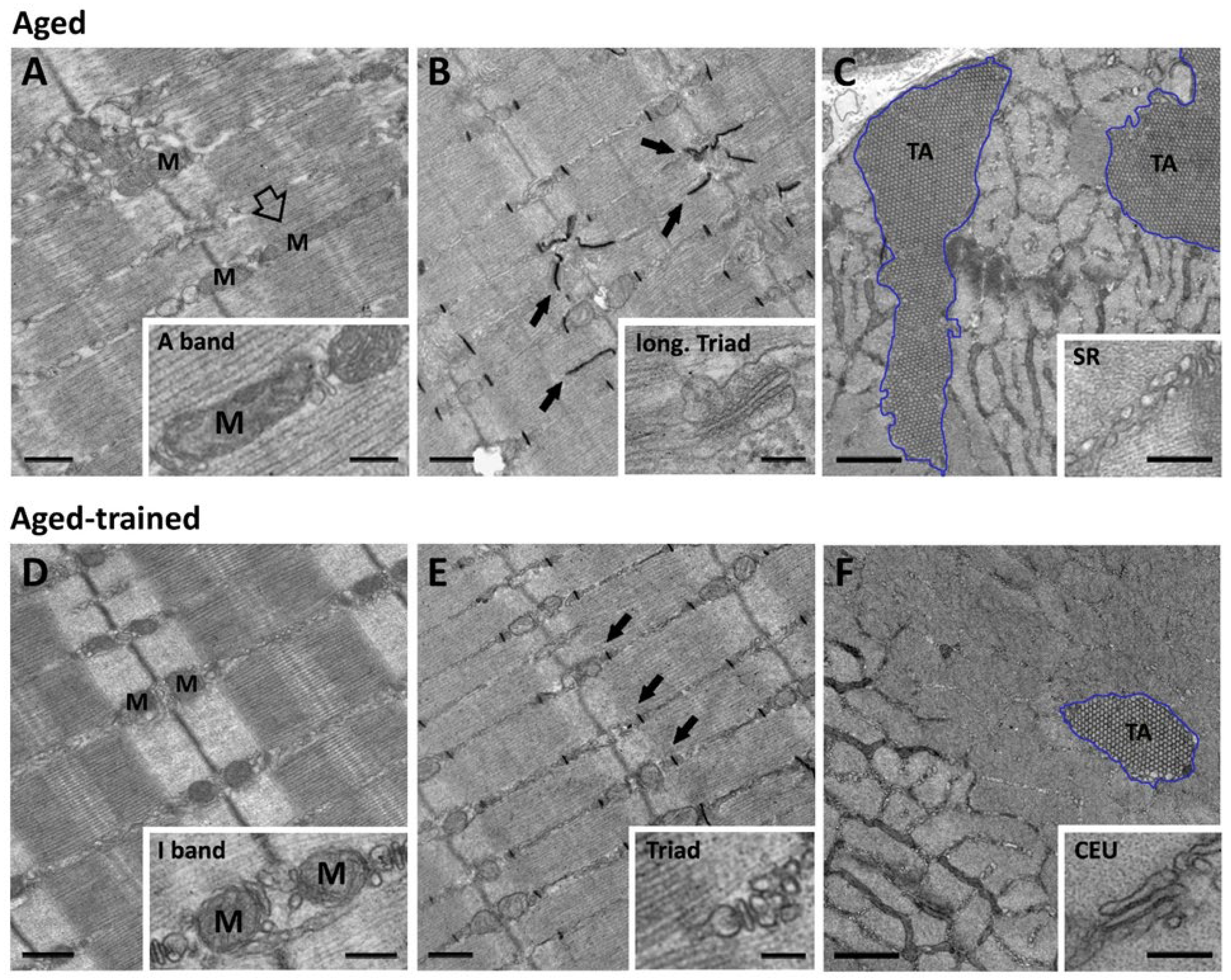

3. Sedentary Aging Compromises the Architecture of Mitochondrial Network and Sarcotubular System

3.1. Uncoupling of Mitochondria from Triads with Increasing Age

3.2. Reductions in Number of Ca2+ Release Sites, i.e., Triads

3.3. Formation of Tubular Aggregates (TAs) and Loss of Ca2+ Entry Units (CEUs)

4. Regular Exercise Prevents Age-Dependent Damage to Mitochondria and Membrane Systems Involved in Ca2+ Handling

4.1. Exercise Maintains Mitochondria–Triad Connectivity During Aging

4.2. Exercise Reduces Tubular Aggregates (TAs) and Maintains SOCE Function

5. Studies in Different Experimental Models Indicate That Age-like Modifications Are Induced by Inactivity and Are Reversible

5.1. Effect of Denervation and Short-Term Immobilization

5.2. Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES), Reinnervation, and Exercise Reverse the Effect of Denervation and Short-Term Immobilization

- a.

- In Pietrangelo et al., 2019 [64], we showed that reinnervation (occurring spontaneously) in rat muscles that were previously denervated by nerve crash completely restored the position of mitochondria at the I band and the transversal organization of the TT network, which was previously compromised by the lack of muscle activity (caused by lack of nerve impulses due to denervation).

- b.

- Two weeks or treadmill rehabilitation (3–4 times a week) in mice that were previously subjected to hind limb unilateral immobilization for six days (by casting) completely rescued the proper intracellular organization of mitochondria, triads, and CEUs (Pietrangelo et al., submitted for publication and [280]).

6. Summary and Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRU | Calcium release unit |

| CEU | Calcium entry unit |

| EM | Electron microscopy |

| EC | Excitation–contraction |

| SR | Sarcoplasmic reticulum |

| SOCE | Store-operated Ca2+ entry |

| TA | Tubular aggregate |

| TT | Transverse tubule |

References

- Rasmussen, H.; Jensen, P.; Lake, W.; Goodman, D.B. Calcium Ion as Second Messenger. Clin. Endocrinol. 1976, 5, 11S–27S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, V.; Creutz, C.E.; Moss, S.E. Annexins: Linking Ca2+ Signalling to Membrane Dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, M. Calcium Ion as a Second Messenger With Special Reference to Excitation-Contraction Coupling. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2006, 100, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolmetsch, R. Excitation-Transcription Coupling: Signaling by Ion Channels to the Nucleus. Sci. STKE 2003, 2003, PE4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapham, D.E. Calcium Signaling. Cell 2007, 131, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, S.; Patergnani, S.; Missiroli, S.; Morciano, G.; Rimessi, A.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Giorgi, C.; Pinton, P. Mitochondrial and Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Homeostasis and Cell Death. Cell Calcium 2018, 69, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkryl, V.M.; Shirokova, N. Transfer and Tunneling of Ca2+ from Sarcoplasmic Reticulum to Mitochondria in Skeletal Muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, R.; Mongillo, M.; Magalhães, P.J.; Pozzan, T. In Vivo Monitoring of Ca2+ Uptake into Mitochondria of Mouse Skeletal Muscle during Contraction. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 166, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, P.; Calderón, J.C. Excitation-Contraction Coupling in Mammalian Skeletal Muscle: Blending Old and Last-Decade Research. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 989796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, G.; Monticelli, H.; Rizzuto, R.; Mammucari, C. The Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake and the Fine-Tuning of Aerobic Metabolism. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 554904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, P.; Guillen, A.; Rojas, H.; Boncompagni, S.; Caputo, C. The Use of CalciumOrange-5N as a Specific Marker of Mitochondrial Ca2+ in Mouse Skeletal Muscle Fibers. Pflug. Arch. 2007, 455, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.E.; Boncompagni, S.; Dirksen, R.T. Sarcoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Symbiosis. Exerc. Sport. Sci. Rev. 2009, 37, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, V.; Csordás, G.; Hajnóczky, G. Interactions between Sarco-Endoplasmic Reticulum and Mitochondria in Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle—Pivotal Roles in Ca2+ and Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 2965–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csordás, G.; Hajnóczky, G. SR/ER-Mitochondrial Local Communication: Calcium and ROS. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandow, A. Excitation-Contraction Coupling in Muscular Response. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1952, 25, 176–201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sandow, A.; Taylor, S.R.; Preiser, H. Role of the Action Potential in Excitation-Contraction Coupling. Fed. Proc. 1965, 24, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M.F.; Rodney, G.G.; Ward, C.W. Local Ca2+ Release Events in Skeletal Muscle. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2004, 25, 587–589. [Google Scholar]

- Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Protasi, F. Ryanodine Receptors of Striated Muscles: A Complex Channel Capable of Multiple Interactions. Physiol. Rev. 1997, 77, 699–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón, J.C.; Bolaños, P.; Caputo, C. The Excitation–Contraction Coupling Mechanism in Skeletal Muscle. Biophys. Rev. 2014, 6, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, D.L.; Wagenknecht, T. Calcium Transport across the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum: Structure and Function of Ca2+-ATPase and the Ryanodine Receptor. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 5274–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ochoa, E.O.; Pratt, S.J.P.; Lovering, R.M.; Schneider, M.F. Critical Role of Intracellular RyR1 Calcium Release Channels in Skeletal Muscle Function and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putney, J.W. A Model for Receptor-Regulated Calcium Entry. Cell Calcium 1986, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, A.B.; Penner, R. Store Depletion and Calcium Influx. Physiol. Rev. 1997, 77, 901–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launikonis, B.S.; Ríos, E. Store-operated Ca2+ Entry during Intracellular Ca2+ Release in Mammalian Skeletal Muscle. J. Physiol. 2007, 583, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launikonis, B.S.; Barnes, M.; Stephenson, D.G. Identification of the Coupling between Skeletal Muscle Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry and the Inositol Trisphosphate Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2941–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurebayashi, N.; Ogawa, Y. Depletion of Ca2+ in the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Stimulates Ca2+ Entry into Mouse Skeletal Muscle Fibres. J. Physiol. 2001, 533, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirksen, R.T. Checking Your SOCCs and Feet: The Molecular Mechanisms of Ca2+ Entry in Skeletal Muscle. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 3139–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelucci, A.; García-Castañeda, M.; Boncompagni, S.; Dirksen, R.T. Role of STIM1/ORAI1-Mediated Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry in Skeletal Muscle Physiology and Disease. Cell Calcium 2018, 76, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protasi, F.; Girolami, B.; Serano, M.; Pietrangelo, L.; Paolini, C. Ablation of Calsequestrin-1, Ca2+ Unbalance, and Susceptibility to Heat Stroke. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1033300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sztretye, M.; Geyer, N.; Vincze, J.; Al-Gaadi, D.; Oláh, T.; Szentesi, P.; Kis, G.; Antal, M.; Balatoni, I.; Csernoch, L.; et al. SOCE Is Important for Maintaining Sarcoplasmic Calcium Content and Release in Skeletal Muscle Fibers. Biophys. J. 2017, 113, 2496–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei-Lapierre, L.; Carrell, E.M.; Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F.; Dirksen, R.T. Orai1-Dependent Calcium Entry Promotes Skeletal Muscle Growth and Limits Fatigue. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilliu, E.; Koenig, S.; Koenig, X.; Frieden, M. Store-Operated Calcium Entry in Skeletal Muscle: What Makes It Different? Cells 2021, 10, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncompagni, S.; Rossi, A.E.; Micaroni, M.; Beznoussenko, G.V.; Polishchuk, R.S.; Dirksen, R.T.; Protasi, F. Mitochondria Are Linked to Calcium Stores in Striated Muscle by Developmentally Regulated Tethering Structures. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, A.E.; Boncompagni, S.; Wei, L.; Protasi, F.; Dirksen, R.T. Differential Impact of Mitochondrial Positioning on Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake and Ca2+ Spark Suppression in Skeletal Muscle. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2011, 301, C1128–C1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Boncompagni, S. The Evolution of the Mitochondria-to-Calcium Release Units Relationship in Vertebrate Skeletal Muscles. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 830573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioretti, C.; Zanetti, G.; Pirazzini, M.; Gherardi, G.; Nogara, L.; Andreotti, R.; Martini, P.; Marcucci, L.; Canato, M.; Nath, S.R.; et al. Defective Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Mitochondrial Respiration Precede Mitochondrial Ca2+ Accumulation in Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy Skeletal Muscle. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, A.; Okada, J.; Washio, T.; Hisada, T.; Sugiura, S. Mitochondrial Colocalization with Ca2+ Release Sites Is Crucial to Cardiac Metabolism. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo-Domingo, J.; Demaurex, N. Calcium Uptake Mechanisms of Mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1797, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzini-Armstrong, C. Studies of the triad. J. Cell Biol. 1970, 47, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Jorgensen, A.O. Structure and Development of E-C Coupling Units in Skeletal Muscle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1994, 56, 509–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flucher, B.E.; Andrews, S.B.; Daniels, M.P. Molecular Organization of Transverse Tubule/Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Junctions during Development of Excitation-Contraction Coupling in Skeletal Muscle. Mol. Biol. Cell 1994, 5, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takekura, H.; Bennett, L.; Tanabe, T.; Beam, K.G.; Franzini-Armstrong, C. Restoration of Junctional Tetrads in Dysgenic Myotubes by Dihydropyridine Receptor CDNA. Biophys. J. 1994, 67, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flucher, B.E.; Franzini-Armstrong, C. Formation of Junctions Involved in Excitation-Contraction Coupling in Skeletal and Cardiac Muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 8101–8106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncompagni, S.; Michelucci, A.; Pietrangelo, L.; Dirksen, R.T.; Protasi, F. Exercise-Dependent Formation of New Junctions That Promote STIM1-Orai1 Assembly in Skeletal Muscle. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14286, Addendum in Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17463. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33063-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelucci, A.; Boncompagni, S.; Pietrangelo, L.; Takano, T.; Protasi, F.; Dirksen, R.T. Pre-Assembled Ca2+ Entry Units and Constitutively Active Ca2+ Entry in Skeletal Muscle of Calsequestrin-1 Knockout Mice. J. Gen. Physiol. 2020, 152, e202012617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelucci, A.; Boncompagni, S.; Pietrangelo, L.; García-Castañeda, M.; Takano, T.; Malik, S.; Dirksen, R.T.; Protasi, F. Transverse Tubule Remodeling Enhances Orai1-Dependent Ca2+ Entry in Skeletal Muscle. Elife 2019, 8, e47576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelucci, A.; Pietrangelo, L.; Rastelli, G.; Protasi, F.; Dirksen, R.T.; Boncompagni, S. Constitutive Assembly of Ca2+ Entry Units in Soleus Muscle from Calsequestrin Knockout Mice. J. Gen. Physiol. 2022, 154, e202213114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasi, F.; Pietrangelo, L.; Boncompagni, S. Improper Remodeling of Organelles Deputed to Ca2+ Handling and Aerobic ATP Production Underlies Muscle Dysfunction in Ageing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasi, F.; Girolami, B.; Roccabianca, S.; Rossi, D. Store-Operated Calcium Entry: From Physiology to Tubular Aggregate Myopathy. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2023, 68, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebashi, S.; Endo, M. Calcium Ion and Muscle Contraction. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1968, 18, 123–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymn, R.W.; Taylor, E.W. Mechanism of Adenosine Triphosphate Hydrolysis by Actomyosin. Biochemistry 1971, 10, 4617–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.P.; Rui, H.; Basilio, D.; Das, A.; Roux, B.; Latorre, R.; Bezanilla, F.; Holmgren, M. Mechanism of Potassium Ion Uptake by the Na+/K+-ATPase. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, H.L. The Importance of the Creatine Kinase Reaction: The Concept of Metabolic Capacitance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonora, M.; Patergnani, S.; Rimessi, A.; De Marchi, E.; Suski, J.M.; Bononi, A.; Giorgi, C.; Marchi, S.; Missiroli, S.; Poletti, F.; et al. ATP Synthesis and Storage. Purinergic Signal. 2012, 8, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, P.A.; Joyner, M.J.; Caiozzo, V.J. ACSM’s Advanced Exercise Physiology; Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Territo, P.R.; Mootha, V.K.; French, S.A.; Balaban, R.S. Ca2+ Activation of Heart Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation: Role of the F0/F1-ATPase. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2000, 278, C423–C435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillin, J.B.; Madden, M.C. The Role of Calcium in the Control of Respiration by Muscle Mitochondria. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1989, 21, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansford, R.G. Relation between Cytosolic Free Ca2+ Concentration and the Control of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase in Isolated Cardiac Myocytes. Biochem. J. 1987, 241, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaeva, E.V.; Shkryl, V.M.; Shirokova, N. Mitochondrial Redox State and Ca2+ Sparks in Permeabilized Mammalian Skeletal Muscle. J. Physiol. 2005, 565, 855–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaevaand, E.V.; Shirokova, N. Metabolic Regulation of Ca2+ Release in Permeabilized Mammalian Skeletal Muscle Fibres. J. Physiol. 2003, 547, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansford, R.G. Role of Calcium in Respiratory Control. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, J.M. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Calcium Uptake Slows down Relaxation in Mitochondria-Rich Skeletal Muscles. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1997, 18, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrangelo, L.; D’Incecco, A.; Ainbinder, A.; Michelucci, A.; Kern, H.; Dirksen, R.T.; Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F. Age-Dependent Uncoupling of Mitochondria from Ca2+ Release Units in Skeletal Muscle. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35358–35371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrangelo, L.; Michelucci, A.; Ambrogini, P.; Sartini, S.; Guarnier, F.A.; Fusella, A.; Zamparo, I.; Mammucari, C.; Protasi, F.; Boncompagni, S. Muscle Activity Prevents the Uncoupling of Mitochondria from Ca2+ Release Units Induced by Ageing and Disuse. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 663, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntinas, L.; Gunter, K.K.; Sparagna, G.C.; Gunter, T.E. The Rapid Mode of Calcium Uptake into Heart Mitochondria (RaM): Comparison to RaM in Liver Mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Bioenerg. 2001, 1504, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutner, G.; Sharma, V.K.; Giovannucci, D.R.; Yule, D.I.; Sheu, S.-S. Identification of a Ryanodine Receptor in Rat Heart Mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 21482–21488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, K.K.; Gunter, T.E. Transport of Calcium by Mitochondria. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1994, 26, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefani, D.; Raffaello, A.; Teardo, E.; Szabò, I.; Rizzuto, R. A Forty-Kilodalton Protein of the Inner Membrane Is the Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter. Nature 2011, 476, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, J.M.; Perocchi, F.; Girgis, H.S.; Plovanich, M.; Belcher-Timme, C.A.; Sancak, Y.; Bao, X.R.; Strittmatter, L.; Goldberger, O.; Bogorad, R.L.; et al. Integrative Genomics Identifies MCU as an Essential Component of the Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter. Nature 2011, 476, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Liu, J.; Nguyen, T.; Liu, C.; Sun, J.; Teng, Y.; Fergusson, M.M.; Rovira, I.I.; Allen, M.; Springer, D.A.; et al. The Physiological Role of Mitochondrial Calcium Revealed by Mice Lacking the Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 1464–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembrowich, W.L.; Quintinskie, J.J.; Li, G. Calcium Uptake in Mitochondria from Different Skeletal Muscle Types. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985, 59, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannella, C.A.; Buttle, K.; Rath, B.K.; Marko, M. Electron Microscopic Tomography of Rat-liver Mitochondria and Their Interactions with the Endoplasmic Reticulum. BioFactors 1998, 8, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csordás, G.; Renken, C.; Várnai, P.; Walter, L.; Weaver, D.; Buttle, K.F.; Balla, T.; Mannella, C.A.; Hajnóczky, G. Structural and Functional Features and Significance of the Physical Linkage Between ER and Mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Ramesh, V.; Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Sheu, S.-S. Transport of Ca2+ from Sarcoplasmic Reticulum to Mitochondria in Rat Ventricular Myocytes. J. Bioenergetics Biomembr. 2000, 32, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, T.; Yamasaki, Y. Scanning Electron-Microscopic Studies on the Three-Dimensional Structure of Mitochondria in the Mammalian Red, White and Intermediate Muscle Fibers. Cell Tissue Res. 1985, 241, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainbinder, A.; Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F.; Dirksen, R.T. Role of Mitofusin-2 in Mitochondrial Localization and Calcium Uptake in Skeletal Muscle. Cell Calcium 2015, 57, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.F. Control of Calcium Release in Functioning Skeletal Muscle Fibers. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1994, 56, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protasi, F. Structural Interaction between RYRs and DHPRs in Calcium Release Units of Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle Cells. Front. Biosci. 2002, 7, A801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebashi, S. Excitation-Contraction Coupling and the Mechanism of Muscle Contraction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1991, 53, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, S.; Ravens, U.; Verkhratsky, A.; Eisner, D. Two Centuries of Excitation–Contraction Coupling. Cell Calcium 2004, 35, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassier, D.E. Sarcomere Mechanics in Striated Muscles: From Molecules to Sarcomeres to Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2017, 313, C134–C145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, W. What Can We Learn from Single Sarcomere and Myofibril Preparations? Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 837611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilbrunn, L.V.; Wiercinski, F.J. The Action of Various Cations on Muscle Protoplasm. J. Cell Comp. Physiol. 1947, 29, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedergerke, R. The Staircase Phenomenon in the Frog’s Ventricle and the Action of Calcium. J. Physiol. 1955, 128, 55P. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbach, W.; Makinose, M. The Calcium Pump of the “Relaxing Granules” of Muscle and Its Dependence on ATP-Splitting. Biochem. Z. 1961, 333, 518–528. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbach, W. Relaxation and the sarcotubular calcium pump. Fed. Proc. 1964, 23, 909–912. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbach, W.; Oetliker, H. Energetics and Electrogenicity of the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Pump. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1983, 45, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.F.; Chandler, W.K. Voltage Dependent Charge Movement in Skeletal Muscle: A Possible Step in Excitation–Contraction Coupling. Nature 1973, 242, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, E.; Pizarro, G. Voltage Sensor of Excitation-Contraction Coupling in Skeletal Muscle. Physiol. Rev. 1991, 71, 849–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos, E.; Ma, J.; González, A. The Mechanical Hypothesis of Excitation—Contraction (EC) Coupling in Skeletal Muscle. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1991, 12, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, E.; Karhanek, M.; Ma, J.; González, A. An Allosteric Model of the Molecular Interactions of Excitation-Contraction Coupling in Skeletal Muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 1993, 102, 449–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkand, R.K.; Niedergerke, R. Heart Action Potential: Dependence on External Calcium and Sodium Ions. Science 1964, 146, 1176–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näbauer, M.; Callewaert, G.; Cleemann, L.; Morad, M. Regulation of Calcium Release Is Gated by Calcium Current, Not Gating Charge, in Cardiac Myocytes. Science 1989, 244, 800–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiato, A. Calcium-Induced Release of Calcium from the Cardiac Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 1983, 245, C1–C14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabiato, A. Simulated Calcium Current Can Both Cause Calcium Loading in and Trigger Calcium Release from the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum of a Skinned Canine Cardiac Purkinje Cell. J. Gen. Physiol. 1985, 85, 291–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannell, M.; Cheng, H.; Lederer, W. The Control of Calcium Release in Heart Muscle. Science 1995, 268, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, M.L.; Thomas, A.P.; Berlin, J.R. Relationship between L-type Ca2+ Current and Unitary Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Release Events in Rat Ventricular Myocytes. J. Physiol. 1999, 516, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, M.L.; Ji, G.; Wang, Y.-X.; Kotlikoff, M.I. Calcium-Induced Calcium Release in Smooth Muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 2000, 115, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bers, D.M. Cardiac Excitation–Contraction Coupling. Nature 2002, 415, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, E.; Brum, G. Involvement of Dihydropyridine Receptors in Excitation–Contraction Coupling in Skeletal Muscle. Nature 1987, 325, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, A.; Imoto, K.; Tanabe, T.; Niidome, T.; Mori, Y.; Takeshima, H.; Narumiya, S.; Numa, S. Primary Structure and Functional Expression of the Cardiac Dihydropyridine-Sensitive Calcium Channel. Nature 1989, 340, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, T.; Takeshima, H.; Mikami, A.; Flockerzi, V.; Takahashi, H.; Kangawa, K.; Kojima, M.; Matsuo, H.; Hirose, T.; Numa, S. Primary Structure of the Receptor for Calcium Channel Blockers from Skeletal Muscle. Nature 1987, 328, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, T.; Beam, K.G.; Adams, B.A.; Niidome, T.; Numa, S. Regions of the Skeletal Muscle Dihydropyridine Receptor Critical for Excitation–Contraction Coupling. Nature 1990, 346, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, T.; Beam, K.G.; Powell, J.A.; Numa, S. Restoration of Excitation—Contraction Coupling and Slow Calcium Current in Dysgenic Muscle by Dihydropyridine Receptor Complementary DNA. Nature 1988, 336, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, V.; Volpe, P. Ryanodine Receptors: How Many, Where and Why? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993, 14, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannini, G.; Sorrentino, V. Molecular Structure and Tissue Distribution of Ryanodine Receptors Calcium Channels. Med. Res. Rev. 1995, 15, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, V. The Ryanodine Receptor Family of Intracellular Calcium Release Channels. Adv. Pharmacol. 1995, 33, 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zorzato, F.; Fujii, J.; Otsu, K.; Phillips, M.; Green, N.M.; Lai, F.A.; Meissner, G.; MacLennan, D.H. Molecular Cloning of CDNA Encoding Human and Rabbit Forms of the Ca2+ Release Channel (Ryanodine Receptor) of Skeletal Muscle Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 2244–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, H.; Nishimura, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Ishida, H.; Kangawa, K.; Minamino, N.; Matsuo, H.; Ueda, M.; Hanaoka, M.; Hirose, T.; et al. Primary Structure and Expression from Complementary DNA of Skeletal Muscle Ryanodine Receptor. Nature 1989, 339, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, J.; Sekiguchi, N.; Rando, T.A.; Allen, P.D.; Beam, K.G. Two Regions of the Ryanodine Receptor Involved in Coupling Withl-Type Ca2+ Channels. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 13403–13406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, B.A.; Imagawa, T.; Campbell, K.P.; Franzini-Armstrong, C. Structural Evidence for Direct Interaction between the Molecular Components of the Transverse Tubule/Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Junction in Skeletal Muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 107, 2587–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasi, F.; Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Flucher, B.E. Coordinated Incorporation of Skeletal Muscle Dihydropyridine Receptors and Ryanodine Receptors in Peripheral Couplings of BC3H1 Cells. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 137, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasi, F.; Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Allen, P.D. Role of Ryanodine Receptors in the Assembly of Calcium Release Units in Skeletal Muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 140, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protasi, F.; Takekura, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.R.W.; Meissner, G.; Allen, P.D.; Franzini-Armstrong, C. RYR1 and RYR3 Have Different Roles in the Assembly of Calcium Release Units of Skeletal Muscle. Biophys. J. 2000, 79, 2494–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasi, F.; Paolini, C.; Nakai, J.; Beam, K.G.; Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Allen, P.D. Multiple Regions of RyR1 Mediate Functional and Structural Interactions with A1S-Dihydropyridine Receptors in Skeletal Muscle. Biophys. J. 2002, 83, 3230–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, J.; Ogura, T.; Protasi, F.; Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Allen, P.D.; Beam, K.G. Functional Nonequality of the Cardiac and Skeletal Ryanodine Receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takekura, H.; Paolini, C.; Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Kugler, G.; Grabner, M.; Flucher, B.E. Differential Contribution of Skeletal and Cardiac II-III Loop Sequences to the Assembly of Dihydropyridine-Receptor Arrays in Skeletal Muscle. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 5408–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLennan, D.H.; Wong, P.T.S. Isolation of a Calcium-Sequestering Protein from Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLennan, D.H.; de Leon, S. [45] Biosynthesis of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1983, 96, 570–579. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.C.; Caswell, A.H.; Talvenheimo, J.A.; Brandt, N.R. Isolation of a Terminal Cisterna Protein Which May Link the Dihydropyridine Receptor to the Junctional Foot Protein in Skeletal Muscle. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 9281–9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell, A.H.; Brandt, N.R.; Brunschwig, J.P.; Purkerson, S. Localization and Partial Characterization of the Oligomeric Disulfide-Linked Molecular Weight 95,000 Protein (Triadin) Which Binds the Ryanodine and Dihydropyridine Receptors in Skeletal Muscle Triadic Vesicles. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 7507–7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Campbell, K.P. Association of Triadin with the Ryanodine Receptor and Calsequestrin in the Lumen of the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 9027–9030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Kelley, J.; Schmeisser, G.; Kobayashi, Y.M.; Jones, L.R. Complex Formation between Junctin, Triadin, Calsequestrin, and the Ryanodine Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 23389–23397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, H.; Shimuta, M.; Komazaki, S.; Ohmi, K.; Nishi, M.; Iino, M.; Miyata, A.; Kangawa, K. Mitsugumin29, a Novel Synaptophysin Family Member from the Triad Junction in Skeletal Muscle. Biochem. J. 1998, 331, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzato, F.; Anderson, A.A.; Ohlendieck, K.; Froemming, G.; Guerrini, R.; Treves, S. Identification of a Novel 45 KDa Protein (JP-45) from Rabbit Sarcoplasmic-Reticulum Junctional-Face Membrane. Biochem. J. 2000, 351, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshima, H. Junctophilins A Novel Family of Junctional Membrane Complex Proteins. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, E.; Györke, S. Calsequestrin, Triadin and More: The Molecules That Modulate Calcium Release in Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 3069–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebbeck, R.T.; Karunasekara, Y.; Board, P.G.; Beard, N.A.; Casarotto, M.G.; Dulhunty, A.F. Skeletal Muscle Excitation–Contraction Coupling: Who Are the Dancing Partners? Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 48, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzini-armstrong, C.; Porter, K.R. Sarcolemmal Invaginations Constituting the T System in Fish Muscle Fibers. J. Cell Biol. 1964, 22, 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzini-Armstrong, C. The Sarcoplasmic Reticulum and the Control of Muscle Contraction. FASEB J. 1999, 13, S266–S270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, C.; Protasi, F.; Franzini-Armstrong, C. The Relative Position of RyR Feet and DHPR Tetrads in Skeletal Muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 342, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikemoto, N.; Ronjat, M.; Meszaros, L.G.; Koshita, M. Postulated Role of Calsequestrin in the Regulation of Calcium Release from Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 6764–6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Kenney, L.J.; Varriano-Marston, E. The Structure of Calsequestrin in Triads of Vertebrate Skeletal Muscle: A Deep-Etch Study. J. Cell Biol. 1987, 105, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F.; Franzini-Armstrong, C. Sequential Stages in the Age-Dependent Gradual Formation and Accumulation of Tubular Aggregates in Fast Twitch Muscle Fibers: SERCA and Calsequestrin Involvement. Age 2012, 34, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurne, A.M.; O’Brien, J.J.; Wingrove, D.; Cherednichenko, G.; Allen, P.D.; Beam, K.G.; Pessah, I.N. Ryanodine Receptor Type 1 (RyR1) Mutations C4958S and C4961S Reveal Excitation-Coupled Calcium Entry (ECCE) Is Independent of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Store Depletion. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 36994–37004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, R.A.; Pessah, I.N.; Beam, K.G. The Skeletal L-Type Ca2+ Current Is a Major Contributor to Excitation-Coupled Ca2+ Entry. J. Gen. Physiol. 2009, 133, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherednichenko, G.; Ward, C.W.; Feng, W.; Cabrales, E.; Michaelson, L.; Samso, M.; López, J.R.; Allen, P.D.; Pessah, I.N. Enhanced Excitation-Coupled Calcium Entry in Myotubes Expressing Malignant Hyperthermia Mutation R163C Is Attenuated by Dantrolene. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 73, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, P.G.; Rao, A. Store-Operated Calcium Entry: Mechanisms and Modulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 460, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, C.; González, M.E.; García, A.M. Calcium Transport in Transverse Tubules Isolated from Rabbit Skeletal Muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr. 1986, 854, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.J.; Place, N.; Westerblad, H. Molecular Basis for Exercise-Induced Fatigue: The Importance of Strictly Controlled Cellular Ca2+ Handling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a029710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brini, M.; Carafoli, E. The Plasma Membrane Ca2+ ATPase and the Plasma Membrane Sodium Calcium Exchanger Cooperate in the Regulation of Cell Calcium. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a004168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balnave, C.D.; Allen, D.G. Evidence for Na+/Ca2+ Exchange in Intact Single Skeletal Muscle Fibers from the Mouse. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 1998, 274, C940–C946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, J.; DiGregorio, P.J.; Yeromin, A.V.; Ohlsen, K.; Lioudyno, M.; Zhang, S.; Safrina, O.; Kozak, J.A.; Wagner, S.L.; Cahalan, M.D.; et al. STIM1, an Essential and Conserved Component of Store-Operated Ca2+ Channel Function. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 169, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, J.; Kim, M.L.; Do Heo, W.; Jones, J.T.; Myers, J.W.; Ferrell, J.E.; Meyer, T. STIM Is a Ca2+ Sensor Essential for Ca2+-Store-Depletion-Triggered Ca2+ Influx. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feske, S.; Gwack, Y.; Prakriya, M.; Srikanth, S.; Puppel, S.-H.; Tanasa, B.; Hogan, P.G.; Lewis, R.S.; Daly, M.; Rao, A. A Mutation in Orai1 Causes Immune Deficiency by Abrogating CRAC Channel Function. Nature 2006, 441, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vig, M.; Peinelt, C.; Beck, A.; Koomoa, D.L.; Rabah, D.; Koblan-Huberson, M.; Kraft, S.; Turner, H.; Fleig, A.; Penner, R.; et al. CRACM1 Is a Plasma Membrane Protein Essential for Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry. Science 2006, 312, 1220–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.S. The Molecular Choreography of a Store-Operated Calcium Channel. Nature 2007, 446, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Xue, J.; Luo, D. Calsequestrin-1 Regulates Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry by Inhibiting STIM1 Aggregation. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 38, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zheng, Y.; Yan, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Putney, J.W.; Luo, D. Retrograde Regulation of STIM1-Orai1 Interaction and Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry by Calsequestrin. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.W.; Pan, Z.; Kim, E.K.; Lee, J.M.; Bhat, M.B.; Parness, J.; Kim, D.H.; Ma, J. A Retrograde Signal from Calsequestrin for the Regulation of Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry in Skeletal Muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 3286–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, J.; Fivaz, M.; Inoue, T.; Meyer, T. Live-Cell Imaging Reveals Sequential Oligomerization and Local Plasma Membrane Targeting of Stromal Interaction Molecule 1 after Ca2+ Store Depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 9301–9306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.M.; Buchanan, J.; Luik, R.M.; Lewis, R.S. Ca2+ Store Depletion Causes STIM1 to Accumulate in ER Regions Closely Associated with the Plasma Membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luik, R.M.; Wu, M.M.; Buchanan, J.; Lewis, R.S. The Elementary Unit of Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry: Local Activation of CRAC Channels by STIM1 at ER–Plasma Membrane Junctions. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.L.; Yeromin, A.V.; Zhang, X.H.-F.; Yu, Y.; Safrina, O.; Penna, A.; Roos, J.; Stauderman, K.A.; Cahalan, M.D. Genome-Wide RNAi Screen of Ca2+ Influx Identifies Genes That Regulate Ca2+ Release-Activated Ca2+ Channel Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 9357–9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.M.; Covington, E.D.; Lewis, R.S. Single-Molecule Analysis of Diffusion and Trapping of STIM1 and Orai1 at Endoplasmic Reticulum–Plasma Membrane Junctions. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 3672–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luik, R.M.; Wang, B.; Prakriya, M.; Wu, M.M.; Lewis, R.S. Oligomerization of STIM1 Couples ER Calcium Depletion to CRAC Channel Activation. Nature 2008, 454, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiber, J.; Hawkins, A.; Zhang, Z.-S.; Wang, S.; Burch, J.; Graham, V.; Ward, C.C.; Seth, M.; Finch, E.; Malouf, N.; et al. STIM1 Signalling Controls Store-Operated Calcium Entry Required for Development and Contractile Function in Skeletal Muscle. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyfenko, A.D.; Dirksen, R.T. Differential Dependence of Store-operated and Excitation-coupled Ca2+ Entry in Skeletal Muscle on STIM1 and Orai1. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 4815–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrell, E.M.; Coppola, A.R.; McBride, H.J.; Dirksen, R.T. Orai1 Enhances Muscle Endurance by Promoting Fatigue-resistant Type I Fiber Content but Not through Acute Store-operated Ca2+ Entry. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 4109–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Medina, J.; Mayoral-Gonzalez, I.; Dominguez-Rodriguez, A.; Gallardo-Castillo, I.; Ribas, J.; Ordoñez, A.; Rosado, J.A.; Smani, T. The Complex Role of Store Operated Calcium Entry Pathways and Related Proteins in the Function of Cardiac, Skeletal and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, M.; Li, T.; Graham, V.; Burch, J.; Finch, E.; Stiber, J.A.; Rosenberg, P.B. Dynamic Regulation of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca(2+) Stores by Stromal Interaction Molecule 1 and Sarcolipin during Muscle Differentiation. Dev. Dyn. 2012, 241, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviluoto, S.; Decuypere, J.-P.; De Smedt, H.; Missiaen, L.; Parys, J.B.; Bultynck, G. STIM1 as a Key Regulator for Ca2+ Homeostasis in Skeletal-Muscle Development and Function. Skelet. Muscle 2011, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launikonis, B.S.; Stephenson, D.G.; Friedrich, O. Rapid Ca2+ Flux through the Transverse Tubular Membrane, Activated by Individual Action Potentials in Mammalian Skeletal Muscle. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.N.; Murphy, R.M.; Cully, T.R.; von Wegner, F.; Friedrich, O.; Launikonis, B.S. Ultra-Rapid Activation and Deactivation of Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry in Skeletal Muscle. Cell Calcium 2010, 47, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darbellay, B.; Arnaudeau, S.; König, S.; Jousset, H.; Bader, C.; Demaurex, N.; Bernheim, L. STIM1- and Orai1-Dependent Store-Operated Calcium Entry Regulates Human Myoblast Differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 5370–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbellay, B.; Arnaudeau, S.; Bader, C.R.; Konig, S.; Bernheim, L. STIM1L Is a New Actin-Binding Splice Variant Involved in Fast Repetitive Ca2+ Release. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 194, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bootman, M.D.; Collins, T.J.; Mackenzie, L.; Roderick, H.L.; Berridge, M.J.; Peppiatt, C.M. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate (2-APB) Is a Reliable Blocker of Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry but an Inconsistent Inhibitor of InsP3-Induced Ca2+ Release. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitt, C.; Strauss, B.; Schwarz, E.C.; Spaeth, N.; Rast, G.; Hatzelmann, A.; Hoth, M. Potent Inhibition of Ca2+ Release-Activated Ca2+ Channels and T-Lymphocyte Activation by the Pyrazole Derivative BTP2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 12427–12437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girolami, B.; Serano, M.; Di Fonso, A.; Paolini, C.; Pietrangelo, L.; Protasi, F. Searching for Mechanisms Underlying the Assembly of Calcium Entry Units: The Role of Temperature and PH. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboloff, J.; Rothberg, B.S.; Madesh, M.; Gill, D.L. STIM Proteins: Dynamic Calcium Signal Transducers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancarella, S.; Wang, Y.; Deng, X.; Landesberg, G.; Scalia, R.; Panettieri, R.A.; Mallilankaraman, K.; Tang, X.D.; Madesh, M.; Gill, D.L. Hypoxia-Induced Acidosis Uncouples the STIM-Orai Calcium Signaling Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 44788–44798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasi, F.; Pietrangelo, L.; Boncompagni, S. Calcium Entry Units (CEUs): Perspectives in Skeletal Muscle Function and Disease. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2021, 42, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, W. ECC Meets CEU—New Focus on the Backdoor for Calcium Ions in Skeletal Muscle Cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 2020, 152, e202012679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolini, C.; Quarta, M.; Nori, A.; Boncompagni, S.; Canato, M.; Volpe, P.; Allen, P.D.; Reggiani, C.; Protasi, F. Reorganized Stores and Impaired Calcium Handling in Skeletal Muscle of Mice Lacking Calsequestrin-1. J. Physiol. 2007, 583, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasi, F.; Paolini, C.; Dainese, M. Calsequestrin-1: A New Candidate Gene for Malignant Hyperthermia and Exertional/Environmental Heat Stroke. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 3095–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dainese, M.; Quarta, M.; Lyfenko, A.D.; Paolini, C.; Canato, M.; Reggiani, C.; Dirksen, R.T.; Protasi, F. Anesthetic-and Heat-induced Sudden Death in Calsequestrin-1-knockout Mice. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canato, M.; Scorzeto, M.; Giacomello, M.; Protasi, F.; Reggiani, C.; Stienen, G.J.M. Massive Alterations of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Free Calcium in Skeletal Muscle Fibers Lacking Calsequestrin Revealed by a Genetically Encoded Probe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22326–22331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzilli, S.; Serano, M.; Pietrangelo, L.; Protasi, F.; Paolini, C. Structural Adaptation of the Excitation–Contraction Coupling Apparatus in Calsequestrin1-Null Mice during Postnatal Development. Biology 2023, 12, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotto, M. Aging, Sarcopenia and Store-Operated Calcium Entry. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 4201–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, A.M.; Zhao, X.; Weisleder, N.; Brotto, L.S.; Bougoin, S.; Nosek, T.M.; Reid, M.; Hardin, B.; Pan, Z.; Ma, J.; et al. Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry (SOCE) Contributes to Normal Skeletal Muscle Contractility in Young but Not in Aged Skeletal Muscle. Aging 2011, 3, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncompagni, S.; Pecorai, C.; Michelucci, A.; Pietrangelo, L.; Protasi, F. Long-Term Exercise Reduces Formation of Tubular Aggregates and Promotes Maintenance of Ca2+ Entry Units in Aged Muscle. Front. Physiol. 2021, 11, 601057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelucci, A.; Paolini, C.; Canato, M.; Wei-Lapierre, L.; Pietrangelo, L.; De Marco, A.; Reggiani, C.; Dirksen, R.T.; Protasi, F. Antioxidants Protect Calsequestrin-1 Knockout Mice from Halothane- and Heat-Induced Sudden Death. Anesthesiology 2015, 123, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, E.O.; Afilalo, J.; Ensrud, K.E.; Kowal, P.; Onder, G.; Fried, L.P. Frailty: Implications for Clinical Practice and Public Health. Lancet 2019, 394, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Sayer, A.A. Sarcopenia. Lancet 2019, 393, 2636–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blane, D.; Netuveli, G.; Montgomery, S.M. Quality of Life, Health and Physiological Status and Change at Older Ages. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A. Ageing and Physiological Functions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1997, 352, 1837–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandervoort, A.A. Aging of the Human Neuromuscular System. Muscle Nerve 2002, 25, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimby, G.; Saltin, B. The Ageing Muscle. Clin. Physiol. 1983, 3, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.C. Neuromuscular Changes with Aging and Sarcopenia. J. Frailty Aging 2019, 8, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.L.; Guralnik, J.M. The Aging of America. Impact on Health Care Costs. JAMA 1990, 263, 2335–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; Shepard, D.S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Roubenoff, R. The Healthcare Costs of Sarcopenia in the United States. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goates, S.; Du, K.; Arensberg, M.B.; Gaillard, T.; Guralnik, J.; Pereira, S.L. Economic Impact of Hospitalizations in US Adults with Sarcopenia. J. Frailty Aging 2019, 8, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellan van Kan, G. Epidemiology and Consequences of Sarcopenia. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.J. What Is Sarcopenia? J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1995, 50A, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedmer, P.; Jung, T.; Castro, J.P.; Pomatto, L.C.D.; Sun, P.Y.; Davies, K.J.A.; Grune, T. Sarcopenia—Molecular Mechanisms and Open Questions. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 65, 101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, I.H. Summary Comments. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1989, 50, 1231–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubenoff, R.; Hughes, V.A. Sarcopenia: Current Concepts. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2000, 55, M716–M724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alchin, D.R. Sarcopenia: Describing Rather than Defining a Condition. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2014, 5, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, W.K.; Williams, J.; Atherton, P.; Larvin, M.; Lund, J.; Narici, M. Sarcopenia, Dynapenia, and the Impact of Advancing Age on Human Skeletal Muscle Size and Strength; a Quantitative Review. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luff, A.R. Age-associated Changes in the Innervation of Muscle Fibers and Changes in the Mechanical Properties of Motor Units. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 854, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, K.E.; Jubrias, S.A.; Esselman, P.C. Oxidative Capacity and Ageing in Human Muscle. J. Physiol. 2000, 526, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanti, S.; Senini, E.; De Lorenzo, R.; Merolla, A.; Santoro, S.; Festorazzi, C.; Messina, M.; Vitali, G.; Sciorati, C.; Manfredi, A.A.; et al. Molecular Constraints of Sarcopenia in the Ageing Muscle. Front. Aging 2025, 6, 1588014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rygiel, K.A.; Picard, M.; Turnbull, D.M. The Ageing Neuromuscular System and Sarcopenia: A Mitochondrial Perspective. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 4499–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzetti, E.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Landi, F.; Picca, A. Mitochondrial Quantity and Quality in Age-Related Sarcopenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.J.; Piasecki, M.; Atherton, P.J. The Age-Related Loss of Skeletal Muscle Mass and Function: Measurement and Physiology of Muscle Fibre Atrophy and Muscle Fibre Loss in Humans. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 47, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tieland, M.; Trouwborst, I.; Clark, B.C. Skeletal Muscle Performance and Ageing. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbono, O.; O’Rourke, K.S.; Ettinger, W.H. Excitation-Calcium Release Uncoupling in Aged Single Human Skeletal Muscle Fibers. J. Membr. Biol. 1995, 148, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbono, O. Expression and Regulation of Excitation-Contraction Coupling Proteins in Aging Skeletal Muscle. Curr. Aging Sci. 2011, 4, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renganathan, M.; Messi, M.L.; Delbono, O. Dihydropyridine Receptor-Ryanodine Receptor Uncoupling in Aged Skeletal Muscle. J. Membr. Biol. 1997, 157, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.; Ohlendieck, K. Excitation-Contraction Uncoupling and Sarcopenia. Basic. Appl. Myol. 2004, 14, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.; Butler-Browne, G.; Erzen, I.; Mouly, V.; Thornell, L.-E.; Wernig, A.; Ohlendieck, K. Persistent Expression of the Alpha1S-Dihydropyridine Receptor in Aged Human Skeletal Muscle: Implications for the Excitation-Contraction Uncoupling Hypothesis of Sarcopenia. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2003, 11, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zampieri, S.; Pietrangelo, L.; Loefler, S.; Fruhmann, H.; Vogelauer, M.; Burggraf, S.; Pond, A.; Grim-Stieger, M.; Cvecka, J.; Sedliak, M.; et al. Lifelong Physical Exercise Delays Age-Associated Skeletal Muscle Decline. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncompagni, S.; d’Amelio, L.; Fulle, S.; Fano, G.; Protasi, F. Progressive Disorganization of the Excitation-Contraction Coupling Apparatus in Aging Human Skeletal Muscle as Revealed by Electron Microscopy: A Possible Role in the Decline of Muscle Performance. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006, 61, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vue, Z.; Garza-Lopez, E.; Neikirk, K.; Katti, P.; Vang, L.; Beasley, H.; Shao, J.; Marshall, A.G.; Crabtree, A.; Murphy, A.C.; et al. 3D Reconstruction of Murine Mitochondria Reveals Changes in Structure during Aging Linked to the MICOS Complex. Aging Cell 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scudese, E.; Marshall, A.G.; Vue, Z.; Exil, V.; Rodriguez, B.I.; Demirci, M.; Vang, L.; López, E.G.; Neikirk, K.; Shao, B.; et al. 3D Mitochondrial Structure in Aging Human Skeletal Muscle: Insights Into MFN-2-Mediated Changes. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.E.; White, K.; Davey, T.; Philips, J.; Ogden, R.T.; Lawless, C.; Warren, C.; Hall, M.G.; Ng, Y.S.; Falkous, G.; et al. Quantitative 3D Mapping of the Human Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Network. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 996–1009.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Lederer, W.J.; Cannell, M.B. Calcium Sparks: Elementary Events Underlying Excitation-Contraction Coupling in Heart Muscle. Science 1993, 262, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Lederer, W.J. Calcium Sparks. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1491–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugorka, A.; Ríos, E.; Blatter, L.A. Imaging Elementary Events of Calcium Release in Skeletal Muscle Cells. Science 1995, 269, 1723–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, E. Ca2+ Release Flux Underlying Ca2+ Transients and Ca2+ Sparks in Skeletal Muscle. Front. Biosci. 2002, 7, A833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingworth, S.; Zhao, M.; Baylor, S.M. The Amplitude and Time Course of the Myoplasmic Free [Ca2+] Transient in Fast-Twitch Fibers of Mouse Muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 1996, 108, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csernoch, L.; Zhou, J.; Stern, M.D.; Brum, G.; Ríos, E. The Elementary Events of Ca2+ Release Elicited by Membrane Depolarization in Mammalian Muscle. J. Physiol. 2004, 557, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostol, S.; Ursu, D.; Lehmann-Horn, F.; Melzer, W. Local Calcium Signals Induced by Hyper-Osmotic Stress in Mammalian Skeletal Muscle Cells. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2009, 30, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salviati, G.; Pierobon-Bormioli, S.; Betto, R.; Damiani, E.; Angelini, C.; Ringel, S.P.; Salvatori, S.; Margreth, A. Tubular Aggregates: Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Origin, Calcium Storage Ability, and Functional Implications. Muscle Nerve 1985, 8, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.L. Tubular Aggregates. Arch. Neurol. 1985, 42, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierobon-Bormioli, S.; Armani, M.; Ringel, S.P.; Angelini, C.; Vergani, L.; Betto, R.; Salviati, G. Familial Neuromuscular Disease with Tubular Aggregates. Muscle Nerve 1985, 8, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Hughes, J.A. Tubular Aggregates in Skeletal Muscle: Their Functional Significance and Mechanisms of Pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 1998, 11, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, W.K.; Bishop, D.W.; Cunningham, G.G. Tubular Aggregates in Type II Muscle Fibers: Ultrastructural and Histochemical Correlation. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1970, 31, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, J.G.; Arts, W.F. Familial Myopathy with Tubular Aggregates. J. Neurol. 1982, 227, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, M.C.; Rossius, M.; Zitzelsberger, M.; Vorgerd, M.; Müller-Felber, W.; Ertl-Wagner, B.; Zhang, Y.; Brinkmeier, H.; Senderek, J.; Schoser, B. 50 Years to Diagnosis: Autosomal Dominant Tubular Aggregate Myopathy Caused by a Novel STIM1 Mutation. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2015, 25, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuma, H.; Saito, F.; Mitsui, J.; Hara, Y.; Hatanaka, Y.; Ikeda, M.; Shimizu, T.; Matsumura, K.; Shimizu, J.; Tsuji, S.; et al. Tubular Aggregate Myopathy Caused by a Novel Mutation in the Cytoplasmic Domain of STIM1. Neurol. Genet. 2016, 2, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesin, V.; Wiley, G.; Kousi, M.; Ong, E.-C.; Lehmann, T.; Nicholl, D.J.; Suri, M.; Shahrizaila, N.; Katsanis, N.; Gaffney, P.M.; et al. Activating Mutations in STIM1 and ORAI1 Cause Overlapping Syndromes of Tubular Myopathy and Congenital Miosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4197–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Y.; Noguchi, S.; Hara, Y.; Hayashi, Y.K.; Motomura, K.; Miyatake, S.; Murakami, N.; Tanaka, S.; Yamashita, S.; Kizu, R.; et al. Dominant Mutations in ORAI1 Cause Tubular Aggregate Myopathy with Hypocalcemia via Constitutive Activation of Store-Operated Ca2+ Channels. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, J.; Chevessier, F.; De Paula, A.M.; Koch, C.; Attarian, S.; Feger, C.; Hantaï, D.; Laforêt, P.; Ghorab, K.; Vallat, J.-M.; et al. Constitutive Activation of the Calcium Sensor STIM1 Causes Tubular-Aggregate Myopathy. Am. J. Human. Genet. 2013, 92, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, J.; Bulla, M.; Urquhart, J.E.; Malfatti, E.; Williams, S.G.; O’Sullivan, J.; Szlauer, A.; Koch, C.; Baranello, G.; Mora, M.; et al. ORAI1 Mutations with Distinct Channel Gating Defects in Tubular Aggregate Myopathy. Hum. Mutat. 2017, 38, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, V.; Del Re, V.; Gamberucci, A.; Polverino, V.; Galli, L.; Rossi, D.; Costanzi, E.; Toniolo, L.; Berti, G.; Malandrini, A.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Three Novel Mutations in the CASQ1 Gene in Four Patients with Tubular Aggregate Myopathy. Hum. Mutat. 2017, 38, 1761–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevessier, F.; Marty, I.; Paturneau-Jouas, M.; Hantai, D.; Verdière-Sahuqué, M. Tubular Aggregates Are from Whole Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Origin: Alterations in Calcium Binding Protein Expression in Mouse Skeletal Muscle during Aging. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2004, 14, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiaffino, S.; Severin, E.; Cantini, M.; Sartore, S. Tubular Aggregates Induced by Anoxia in Isolated Rat Skeletal Muscle. Lab. Investig. 1977, 37, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Weisleder, N.; Thornton, A.; Oppong, Y.; Campbell, R.; Ma, J.; Brotto, M. Compromised Store-operated Ca2+ Entry in Aged Skeletal Muscle. Aging Cell 2008, 7, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Mu, J. Resistance Exercise Training Improves Disuse-Induced Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Humans: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, M.J.; Thalacker-Mercer, A.; Mayhew, D.L.; Kelly, N.A.; Tuggle, S.C.; Merritt, E.K.; Brown, C.J.; Windham, S.T.; Dell’Italia, L.J.; Bickel, C.S.; et al. Randomized, Four-Arm, Dose-Response Clinical Trial to Optimize Resistance Exercise Training for Older Adults with Age-Related Muscle Atrophy. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 99, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, R.; Handschin, C. Molecular Aspects of the Exercise Response and Training Adaptation in Skeletal Muscle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 223, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brightwell, C.R.; Markofski, M.M.; Moro, T.; Fry, C.S.; Porter, C.; Volpi, E.; Rasmussen, B.B. Moderate-Intensity Aerobic Exercise Improves Skeletal Muscle Quality in Older Adults. Transl. Sports Med. 2019, 2, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harber, M.P.; Konopka, A.R.; Douglass, M.D.; Minchev, K.; Kaminsky, L.A.; Trappe, T.A.; Trappe, S. Aerobic Exercise Training Improves Whole Muscle and Single Myofiber Size and Function in Older Women. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 297, R1452–R1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodine, S.C.; Stitt, T.N.; Gonzalez, M.; Kline, W.O.; Stover, G.L.; Bauerlein, R.; Zlotchenko, E.; Scrimgeour, A.; Lawrence, J.C.; Glass, D.J.; et al. Akt/MTOR Pathway Is a Crucial Regulator of Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy and Can Prevent Muscle Atrophy in Vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, S.; Handschin, C.; St.-Pierre, J.; Spiegelman, B.M. AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) Action in Skeletal Muscle via Direct Phosphorylation of PGC-1α. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12017–12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawley, J.A. Molecular Responses to Strength and Endurance Training: Are They Incompatible? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 34, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera, D.M.; Smiles, W.J.; Hawley, J.A. Exercise-Induced Skeletal Muscle Signaling Pathways and Human Athletic Performance. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 98, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, M.D.; Papst, R.R.; Farinatti, P. Moderators of Strength Gains and Hypertrophy in Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 2189–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.; Brightwell, C.R.; Volpi, E.; Rasmussen, B.B.; Fry, C.S. Resistance Exercise Training Promotes Fiber Type-Specific Myonuclear Adaptations in Older Adults. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 128, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straight, C.R.; Fedewa, M.V.; Toth, M.J.; Miller, M.S. Improvements in Skeletal Muscle Fiber Size with Resistance Training Are Age-Dependent in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 129, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bo, H.; Zhang, Y. Endurance Exercise-Induced Histone Methylation Modification Involved in Skeletal Muscle Fiber Type Transition and Mitochondrial Biogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdijk, L.B.; Gleeson, B.G.; Jonkers, R.A.M.; Meijer, K.; Savelberg, H.H.C.M.; Dendale, P.; van Loon, L.J.C. Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy Following Resistance Training Is Accompanied by a Fiber Type-Specific Increase in Satellite Cell Content in Elderly Men. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009, 64, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, S.; Mammucari, C.; Romanello, V.; Barberi, L.; Pietrangelo, L.; Fusella, A.; Mosole, S.; Gherardi, G.; Höfer, C.; Löfler, S.; et al. Physical Exercise in Aging Human Skeletal Muscle Increases Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Expression Levels and Affects Mitochondria Dynamics. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4, e13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosole, S.; Carraro, U.; Kern, H.; Loefler, S.; Fruhmann, H.; Vogelauer, M.; Burggraf, S.; Mayr, W.; Krenn, M.; Paternostro-Sluga, T.; et al. Long-Term High-Level Exercise Promotes Muscle Reinnervation With Age. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 73, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintignac, L.A.; Brenner, H.-R.; Rüegg, M.A. Mechanisms Regulating Neuromuscular Junction Development and Function and Causes of Muscle Wasting. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 809–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.C.; Van Remmen, H. Age-Associated Alterations of the Neuromuscular Junction. Exp. Gerontol. 2011, 46, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiaffino, S.; Dyar, K.A.; Ciciliot, S.; Blaauw, B.; Sandri, M. Mechanisms Regulating Skeletal Muscle Growth and Atrophy. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 4294–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.R.; Shah, S.B.; Lovering, R.M. The Neuromuscular Junction: Roles in Aging and Neuromuscular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, M.R.; Rice, C.L.; Vandervoort, A.A. Age-Related Changes in Motor Unit Function. Muscle Nerve 1997, 20, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.J.; Vandervoort, A.A.; Taylor, A.W.; Brown, W.F. Effects of Motor Unit Losses on Strength in Older Men and Women. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993, 74, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L. The Age-related Motor Disability: Underlying Mechanisms in Skeletal Muscle at the Motor Unit, Cellular and Molecular Level. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1998, 163, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aagaard, P.; Suetta, C.; Caserotti, P.; Magnusson, S.P.; Kjær, M. Role of the Nervous System in Sarcopenia and Muscle Atrophy with Aging: Strength Training as a Countermeasure. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexell, J. Evidence for Nervous System Degeneration with Advancing Age. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 1011S–1013S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, R.J.; Vukovic, J.; Dunlop, S.; Grounds, M.D.; Shavlakadze, T. Striking Denervation of Neuromuscular Junctions without Lumbar Motoneuron Loss in Geriatric Mouse Muscle. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, C.; Franzini, C. An Electron Microscope Study of Denervation Atrophy in Red and White Skeletal Muscle Fibers. J. Cell Biol. 1963, 17, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.G.; Franzini-Armstrong, C. Myology, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, B.M. The Biology of Long-Term Denervated Skeletal Muscle. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2014, 24, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, U.; Kern, H.; Gava, P.; Hofer, C.; Loefler, S.; Gargiulo, P.; Mosole, S.; Zampieri, S.; Gobbo, V.; Ravara, B.; et al. Biology of Muscle Atrophy and of Its Recovery by FES in Aging and Mobility Impairments: Roots and by-Products. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2015, 25, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirago, G.; Pellegrino, M.A.; Bottinelli, R.; Franchi, M.V.; Narici, M. V Loss of Neuromuscular Junction Integrity and Muscle Atrophy in Skeletal Muscle Disuse. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 83, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takekura, H.; Kasuga, N.; Kitada, K.; Yoshioka, T. Morphological Changes in the Triads and Sarcoplasmic Reticulum of Rat Slow and Fast Muscle Fibres Following Denervation and Immobilization. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1996, 17, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mödlin, M.; Forstner, C.; Hofer, C.; Mayr, W.; Richter, W.; Carraro, U.; Protasi, F.; Kern, H. Electrical Stimulation of Denervated Muscles: First Results of a Clinical Study. Artif. Organs 2005, 29, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, Z.; Salmons, S.; Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F.; Russold, M.; Lanmuller, H.; Mayr, W.; Sutherland, H.; Jarvis, J.C. Effects of Chronic Electrical Stimulation on Long-Term Denervated Muscles of the Rabbit Hind Limb. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2007, 28, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, Z.; Sutherland, H.; Lanmüller, H.; Russold, M.F.; Unger, E.; Bijak, M.; Mayr, W.; Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F.; Salmons, S.; et al. Atrophy, but Not Necrosis, in Rabbit Skeletal Muscle Denervated for Periods up to One Year. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2007, 292, C440–C451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squecco, R.; Carraro, U.; Kern, H.; Pond, A.; Adami, N.; Biral, D.; Vindigni, V.; Boncompagni, S.; Pietrangelo, T.; Bosco, G.; et al. A Subpopulation of Rat Muscle Fibers Maintains an Assessable Excitation-Contraction Coupling Mechanism After Long-Standing Denervation Despite Lost Contractility. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2009, 68, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, H.; Boncompagni, S.; Rossini, K.; Mayr, W.; Fanò, G.; Zanin, M.E.; Podhorska-Okolow, M.; Protasi, F.; Carraro, U. Long-Term Denervation in Humans Causes Degeneration of Both Contractile and Excitation-Contraction Coupling Apparatus, Which Is Reversible by Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES): A Role for Myofiber Regeneration? J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2004, 63, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncompagni, S.; Kern, H.; Rossini, K.; Hofer, C.; Mayr, W.; Carraro, U.; Protasi, F. Structural Differentiation of Skeletal Muscle Fibers in the Absence of Innervation in Humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19339–19344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, H.; Carraro, U.; Adami, N.; Hofer, C.; Loefler, S.; Vogelauer, M.; Mayr, W.; Rupp, R.; Zampieri, S. One Year of Home-Based Daily FES in Complete Lower Motor Neuron Paraplegia: Recovery of Tetanic Contractility Drives the Structural Improvements of Denervated Muscle. Neurol. Res. 2010, 32, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flucher, B.E.; Takekura, H.; Franzini-Armstrong, C. Development of the Excitation-Contraction Coupling Apparatus in Skeletal Muscle: Association of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum and Transverse Tubules with Myofibrils. Dev. Biol. 1993, 160, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangelo, L.; Brasile, A.; Girolami, B.; Ravara, B.; Protasi, F. Mimicking disuse and rehabilitation in a mouse model. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2023, 33, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Doucet, B.M.; Lam, A.; Griffin, L. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation for Skeletal Muscle Function. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2012, 85, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Atkins, K.D.; Bickel, C.S. Effects of Functional Electrical Stimulation on Muscle Health after Spinal Cord Injury. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2021, 60, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamian, B.A.; Siegel, N.; Nourie, B.; Serruya, M.D.; Heary, R.F.; Harrop, J.S.; Vaccaro, A.R. The Role of Electrical Stimulation for Rehabilitation and Regeneration after Spinal Cord Injury. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2022, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, H.; Barberi, L.; Löfler, S.; Sbardella, S.; Burggraf, S.; Fruhmann, H.; Carraro, U.; Mosole, S.; Sarabon, N.; Vogelauer, M.; et al. Electrical Stimulation Counteracts Muscle Decline in Seniors. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, P.; Boncompagni, S.; Pietrangelo, L.; Galli, L.; Pierantozzi, E.; Rossi, D.; Fusella, A.; Caulo, M.; Kern, H.; Sorrentino, V.; et al. Functional Electrical Stimulation: A Possible Strategy to Improve Muscle Function in Central Core Disease? Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, U.; Boncompagni, S.; Gobbo, V.; Rossini, K.; Zampieri, S.; Mosole, S.; Ravara, B.; Nori, A.; Stramare, R.; Ambrosio, F.; et al. Persistent Muscle Fiber Regeneration in Long Term Denervation. Past, Present, Future. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2015, 25, 4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biral, D.; Kern, H.; Adami, N.; Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F.; Carraro, U. Atrophy-resistant fibers in permanent peripheral denervation of human skeletal muscle. Neurol. Res. 2008, 30, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chan, H.; Evans, C.; Maddocks, M. The Association between Sedentary Behaviour and Sarcopenia in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hämäläinen, O.; Tirkkonen, A.; Savikangas, T.; Alén, M.; Sipilä, S.; Hautala, A. Low Physical Activity Is a Risk Factor for Sarcopenia: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Two Exercise Trials on Community-Dwelling Older Adults. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Lee, R.Y.W. Physical Activity Reduces the Incidence of Sarcopenia in Middle-Aged Adults. Ageing Int. 2025, 50, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, L.; You, W.; Shan, T. Myokines Mediate the Cross Talk between Skeletal Muscle and Other Organs. J. Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 2393–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.K.; Graham, Z.A.; Cardozo, C.P. Myokines in Skeletal Muscle Physiology and Metabolism: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Acta Physiol. 2020, 228, e13367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severinsen, M.C.K.; Pedersen, B.K. Muscle-Organ Crosstalk: The Emerging Roles of Myokines. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevendonk, L.; Connell, N.J.; McCrum, C.; Fealy, C.E.; Bilet, L.; Bruls, Y.M.H.; Mevenkamp, J.; Schrauwen-Hinderling, V.B.; Jörgensen, J.A.; Moonen-Kornips, E.; et al. Impact of Aging and Exercise on Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Capacity, Energy Metabolism, and Physical Function. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, K.R.; Bigelow, M.L.; Kahl, J.; Singh, R.; Coenen-Schimke, J.; Raghavakaimal, S.; Nair, K.S. Decline in Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Function with Aging in Humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5618–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broskey, N.T.; Greggio, C.; Boss, A.; Boutant, M.; Dwyer, A.; Schlueter, L.; Hans, D.; Gremion, G.; Kreis, R.; Boesch, C.; et al. Skeletal Muscle Mitochondria in the Elderly: Effects of Physical Fitness and Exercise Training. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 1852–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Protasi, F.; Serano, M.; Brasile, A.; Pietrangelo, L. Exercise Protects Skeletal Muscle Fibers from Age-Related Dysfunctional Remodeling of Mitochondrial Network and Sarcotubular System. Cells 2026, 15, 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030248

Protasi F, Serano M, Brasile A, Pietrangelo L. Exercise Protects Skeletal Muscle Fibers from Age-Related Dysfunctional Remodeling of Mitochondrial Network and Sarcotubular System. Cells. 2026; 15(3):248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030248

Chicago/Turabian StyleProtasi, Feliciano, Matteo Serano, Alice Brasile, and Laura Pietrangelo. 2026. "Exercise Protects Skeletal Muscle Fibers from Age-Related Dysfunctional Remodeling of Mitochondrial Network and Sarcotubular System" Cells 15, no. 3: 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030248

APA StyleProtasi, F., Serano, M., Brasile, A., & Pietrangelo, L. (2026). Exercise Protects Skeletal Muscle Fibers from Age-Related Dysfunctional Remodeling of Mitochondrial Network and Sarcotubular System. Cells, 15(3), 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030248