From Dish to Trial: Building Translational Models of ALS

Highlights

- Patient-derived iPSCs enable human-relevant modeling of ALS pathology.

- 3D cultures and ALS-on-a-chip systems improve mechanistic understanding of ALS.

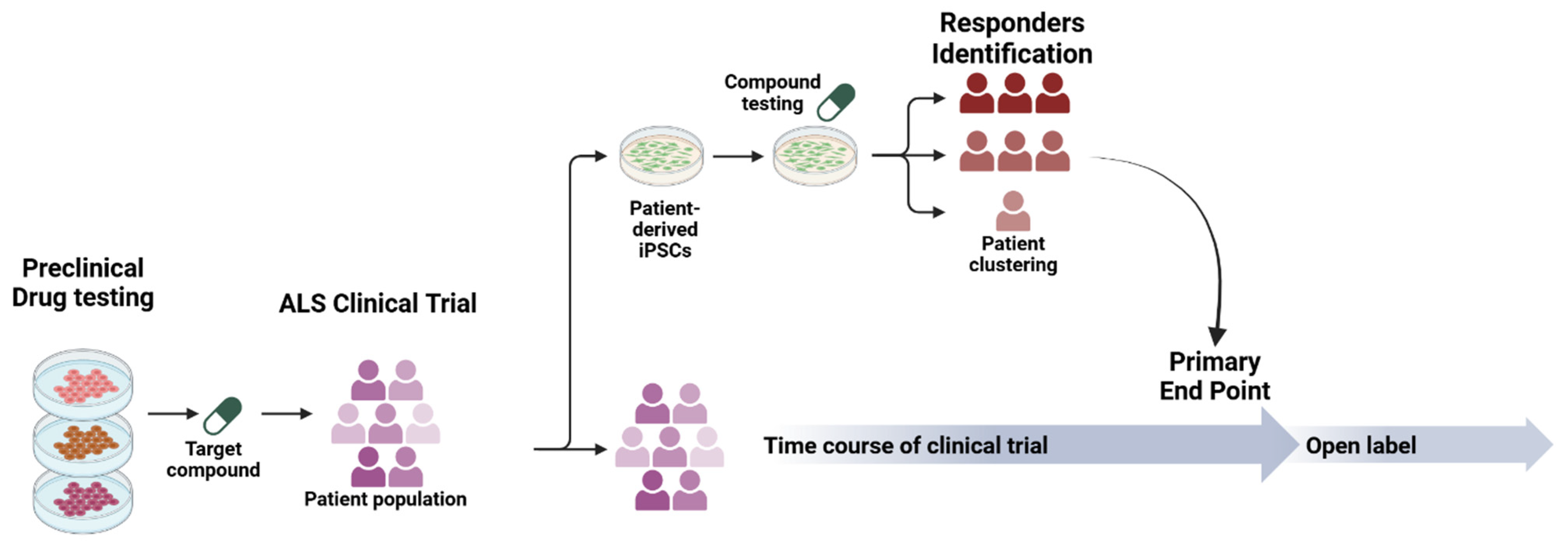

- Large-scale sporadic cohorts may support ALS clinical trials.

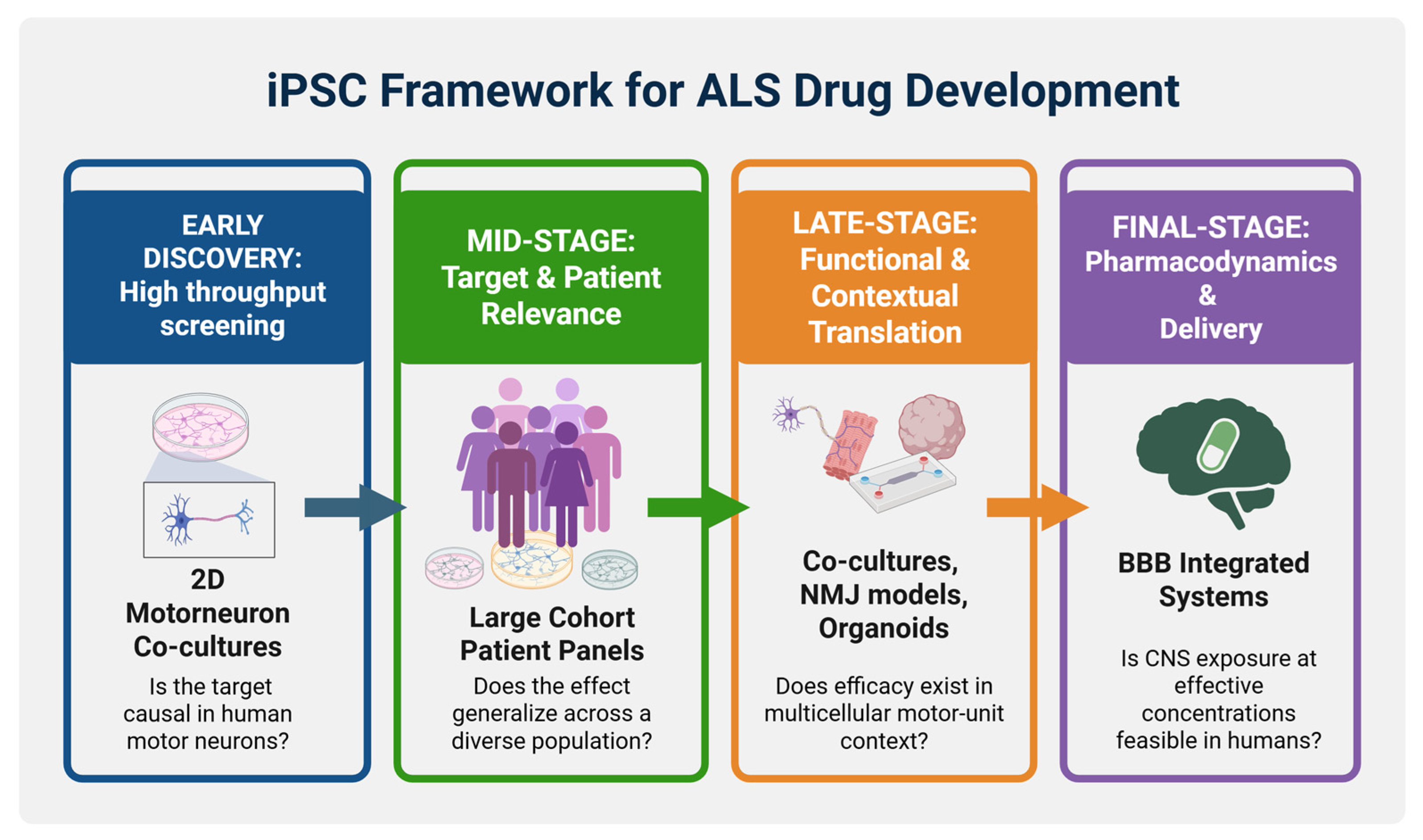

- Proposed iPSC framework for ALS drug development.

Abstract

1. Introduction to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

2. The Evolution of iPSC Technologies Enabling ALS Modeling

3. Emerging 3D Platforms Paving the Way to Faithful ALS Modeling: Focus on the NMJ

| “ALS-on-a-Chip” Motor Unit [39] | Sensorimotor Organoids [40] | Neuromuscular Organoids [41] | Cortico-Motor Assembloids [60] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model description | Compartmentalized microfluidic 3D motor-unit chip combining 3D iPSC-derived skeletal muscle bundles (on pillars) with optogenetic (ChR2) MN spheroids to form NMJs, with additional iPSC-derived endothelial cell (iEC) barrier | Adherent neuromesodermal “sensorimotor organoid” cultures containing motor neurons + skeletal muscle + sensory neurons, astrocytes, microglia, vasculature, forming NMJs across many iPSC lines (patient-derived + isogenic fALS edits) | “Trunk” neuromuscular organoids derived from C9orf72 ALS iPSCs + isogenic controls, comprising spinal cord neural and peripheral muscular tissues (incl. Schwann cells), designed to model spinal/peripheral neuromuscular pathology | Modular fusion of cortical spheroids + hindbrain/cervical spinal cord spheroids + skeletal muscle spheroids to self-assemble a multi-synaptic cortico-spinal–muscle circuit in 3D |

| ALS model | sALS | fALS | C9orf72 ALS | - |

| Functional readouts | Stimulation-evoked muscle contraction quantified (pillar deflection/force); MN viability and NMJ formation | Motor neuron-dependent muscle contractions (spontaneous and optogenetically evoked); NMJ structural metrics (α-BTX AChR clusters apposed to presynaptic markers; EM confirmation) and innervation/NMJ area quantification | Contractile weakness/reduced contractile frequency, denervated NMJs, and neural activity readouts, including MEA-based assessments | Circuit function measured by muscle contraction triggered by glutamate uncaging or optogenetic stimulation of cortex; calcium imaging, rabies tracing, and patch-clamp to confirm connectivity |

| ALS phenotype captured | ALS MNs showed slower neurite outgrowth, reduced NMJ formation, weaker contractions, and increased muscle apoptosis/atrophy signals vs. control motor units | Across ALS patient lines and isogenic fALS edits, organoids showed NMJ impairment, detected by reduced contraction and immunocytochemical NMJ/innervation deficits (e.g., reduced innervated NMJs/NMJ area in specific genotypes) | C9-ALS NMOs recapitulated peripheral ALS-like phenotypes: contraction weakness, neural denervation, loss of Schwann cells, plus C9 hallmarks (RNA foci and DPR proteins) in neurons/astrocytes | Platform development not ALS disease model |

| Functional pharmacology | Rapamycin and bosutinib and co-treatment improved contraction-related deficits and reduced muscle apoptosis | - | Acute GSK2606414 (UPR inhibitor) increased glutamatergic muscular contraction and reduced DPR and autophagy-related readouts in the model | - |

4. Modeling Sporadic ALS

| Study | Type of Study | iPSC Model | Differentiated Cell Type | Observed Phenotypes (sALS-Relevant) | Pharmacological Treatments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [61] | Patient iPSC disease modeling | Patient fibroblast-derived iPSCs (sALS + controls; cohort study) | iPSC-MNs | De novo TDP-43 aggregation in motor neurons from 3 sALS patients; aggregates recapitulated pathology seen in a matched postmortem sample | Digoxin as an example of TDP-43 aggregation modulator |

| [62] | Hallmark pathology modeling (familial + sporadic ALS) | Sendai virus–reprogrammed fibroblast iPSCs (2 sALS) + familial (TARDBP G298S); TALEN-edited H9 ESC AAVS locus model | iPSC-/ESC-MNs and non-MNs | TDP-43 aggregates in surviving MNs (fALS + sALS); ↑ neurofilament inclusions in ALS MNs; ↓ neurite mitochondrial density vs. controls; MNs show greater vulnerability under stress with apoptotic activation | MG132 (proteasome inhibitor) used as challenge → TDP-43 translocation, NF inclusions, impaired mitochondrial distribution, caspase-3 activation |

| [63] | Transcriptomics/gene expression profiling | sALS + control iPSC lines generated from motor nerve fibroblasts | iPSC-MNs | Gene expression dysregulation strongly associated with mitochondrial function and processes linked to motor neuron degeneration | - |

| [64] | Differentiation protocol + sALS phenotype readout | sALS + control iPSC lines | Cervical spinal motor neurons (csMNs) | Detection of hyperexcitability phenotypes in sALS iPSC-csMNs. | - |

| [66] | Early-mechanism study (axon biology) | sALS + control iPSC lines | iPSC-MNs, NMJ-related assays | Early phenotypes: impaired axonal transport, defective axonal outgrowth, reduced NMJ formation; transcriptomics implicate axon guidance pathway dysregulation including EphA4 and DCC upregulation | - |

| [67] | Population-scale iPSC disease modeling + phenotypic clustering + candidate therapy | Large panel of patient-derived iPSC models of sALS | iPSC-MNs (heterogeneity-focused) | Heterogeneous neuronal degeneration patterns, abnormal protein aggregate types, differing cell-death mechanisms, and variable onset/progression in vitro; case clustering framework across sALS models | Identified ropinirole as a multi-phenotype rescue candidate across subclassified sALS models |

| [68] | Large-scale resource/biobank + multi-omics + clinical linkage | Patient-derived iPSC lines (blood-derived), >1000 ALS participants with longitudinal data | iPSC-MNs + multi-omics (WGS, RNA, ATAC, proteomics) + clinical/smartphone data | Resource description (not a single-phenotype report), subtype discovery via integrated clinical–molecular signatures; open sharing portal | - |

| [70] | Large-scale differentiation/QC resource | 341 ALS + 92 control iPSC lines from the Answer ALS consortium | iPSC-MNs | iPSC cohort characterization across 92 controls + 341 ALS motor neuron cultures; identified cell composition and sex as major sources of variability affecting downstream analyses | - |

| [71] | Epigenomics (ATAC-seq) at scale | 380 ALS + 80 control iPSC lines from the Answer ALS consortium | iPSC-MNs | Chromatin accessibility by ATAC-seq strongly influenced by sex, iPSC origin, ancestry, sequencing variance ALS-specific signals post-correction ATAC features can predict disease progression rates comparably to biomarker/clinical methods | - |

| [72] | Population-scale iPSC neuron study of TDP-43 loss-of-function signatures | iPSC-derived neurons (iPSNs) from 180 individuals (controls, C9orf72 ALS/FTD, and sALS) | iPSC-derived neurons (iPSNs); qRT-PCR panel + patient-matched postmortem validation | Identified variable, time-dependent molecular signatures of TDP-43 loss of function in iPSNs; same signatures seen in postmortem brain tissue from the same patients; linked nuclear pore integrity to TDP-43 dysfunction | POM121 reduction (nuclear pore injury) was sufficient to reproduce TDP-43-related molecular changes; repairing nuclear pore injury restored disrupted gene processing |

| [73] | Large-scale phenotypic screening + drug screening | iPSC library from 100 sALS patients | iPSC-MNs population-wide phenotypic screening | sALS MNs show reduced survival, accelerated neurite degeneration (correlating with donor survival), and transcriptional dysregulation; screen of prior ALS trial drugs shows 97% failed to mitigate neurodegeneration | Riluzole rescued neurodegeneration phenotypes; combinatorial testing identified baricitinib + memantine + riluzole as a promising combination |

| [39] | 3D microphysiological ALS-on-a-chip motor unit | iPSC-derived optogenetic MN spheroids from a sALS patient + iPSC-derived skeletal muscle bundles | Microfluidic 3D NMJ model; optogenetic stimulation of MNs → muscle contraction readouts + iPSC-derived ECs (iECs) barrier | ALS motor unit shows fewer muscle contractions, MN degradation, and increased muscle apoptosis vs. non-ALS | Muscle contraction deficits improved with rapamycin and bosutinib (single and co-treatment); recovery associated with upregulated autophagy and TDP-43 degradation in MNs |

| [74] | Organ-on-chip (microfluidic) sALS model with BBB-like barrier | iPSC-MNs from early-onset sALS patients; iPSC-derived brain microvascular endothelial-like cells | Spinal cord chip (SC-chip) with flow + integrated BBB-like barrier | Flow improved maturation/health; transcriptomic/proteomic differences include increased neurofilaments; snRNA-seq identifies MN subpopulations and ALS-specific dysregulation of glutamatergic and synaptic signaling | - |

5. From Dish to Clinic: Translating Findings to Effective Therapies in ALS

5.1. iPSC-Informed Clinical Trials in ALS

| Drug | Class | iPSC Model (Gene/Mutation) | Phenotype Rescue In Vitro | Clinical Trial and Trial ID | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ezogabine/Retigabine | Kv7 (KCNQ2/3) potassium-channel opener | iPSC-MNs from fALS (SOD1 A4V × 2 lines, G85S, D90A, C9orf72 HRE × 2 lines, and FUS M511FS, H517Q) | Normalized hyperexcitability (all genes), reduced ER stress markers (SOD1A4V/+), improved iPSC-MN survival (SOD1A4V/+) | NCT02450552 phase 2 ezogabine PD trial in ALS (completed) | [46,75] |

| Bosutinib | Src/c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor | iPSC-MNs from fALS (SOD1 H46R, SOD1 L144FVX, TARDBP M337V) and sALS patients | Enhanced autophagy, reduced misfolded SOD1 and TDP-43 aggregates, restored mitochondrial homeostasis and improved iPSC-MN survival | NCT04744532 iDReAM phase 1/2 in ALS (ongoing) | [77,78] |

| Ropinirole | Dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonist | iPSC-sMNs from sALS patients | Rescued neurite retraction, autophagy defects, oxidative stress and cell death | UMIN000034954–ROPALS phase 1/2a (completed) | [67,69] |

| BIIB078 (IONIS-C9Rx) | ASO targeting C9orf72 sense repeat-containing RNA | iPSC-MNs from C9orf72 HRE ALS patients | Suppressed RNA foci, lowered DPRs and partially normalized gene expression | NCT03626012 phase 1 MAD safety/PK in C9-ALS (completed, no efficacy, program stopped); NCT04288856 open-label extension (terminated) | [79,80] |

| WVE-004 | Stereopure ASO targeting repeat-containing C9orf72 transcripts | iPSC-MNs and other neurons from C9orf72 HREALS and FTD patients | Selectively reduced repeat-containing C9orf72 transcripts, RNA foci and DPRs in C9 iPSC-MNs while sparing normal C9orf72 protein | NCT04931862 FOCUS-C9 phase 1b/2a in C9-ALS/C9-FTD (terminated after lack of clinical benefit despite target engagement) | [81] |

5.2. Challenges and Future Directions for Translational iPSC Models in ALS

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, J.; Kim, J.-E.; Song, T.-J. The Global Burden of Motor Neuron Disease: An Analysis of the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 864339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.A.; Lally, C.; Kupelian, V.; Flanders, W.D. Estimated Prevalence and Incidence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and SOD1 and C9orf72 Genetic Variants. Neuroepidemiology 2021, 55, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balendra, R.; Isaacs, A.M. C9orf72-Mediated ALS and FTD: Multiple Pathways to Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberio, J.; Lally, C.; Kupelian, V.; Hardiman, O.; Flanders, W.D. Estimated Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Proportion: A Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurol. Genet. 2023, 9, e200109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renton, A.E.; Majounie, E.; Waite, A.; Simón-Sánchez, J.; Rollinson, S.; Gibbs, J.R.; Schymick, J.C.; Laaksovirta, H.; van Swieten, J.C.; Myllykangas, L.; et al. A Hexanucleotide Repeat Expansion in C9ORF72 Is the Cause of Chromosome 9p21-Linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 2011, 72, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJesus-Hernandez, M.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Boeve, B.F.; Boxer, A.L.; Baker, M.; Rutherford, N.J.; Nicholson, A.M.; Finch, N.A.; Flynn, H.; Adamson, J.; et al. Expanded GGGGCC Hexanucleotide Repeat in Noncoding Region of C9ORF72 Causes Chromosome 9p-Linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 2011, 72, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçimen, F.; Lopez, E.R.; Landers, J.E.; Nath, A.; Chiò, A.; Chia, R.; Traynor, B.J. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Translating Genetic Discoveries into Therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, A.E.; Chiò, A.; Traynor, B.J. State of Play in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Genetics. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.N.; Ticozzi, N.; Fallini, C.; Gkazi, A.S.; Topp, S.; Kenna, K.P.; Scotter, E.L.; Kost, J.; Keagle, P.; Miller, J.W.; et al. Exome-Wide Rare Variant Analysis Identifies TUBA4A Mutations Associated with Familial ALS. Neuron 2014, 84, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.O.; Pioro, E.P.; Boehringer, A.; Chia, R.; Feit, H.; Renton, A.E.; Pliner, H.A.; Abramzon, Y.; Marangi, G.; Winborn, B.J.; et al. Mutations in the Matrin 3 Gene Cause Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, S.; Ait-El-Mkadem, S.; Chaussenot, A.; Genin, E.C.; Lacas-Gervais, S.; Fragaki, K.; Berg-Alonso, L.; Kageyama, Y.; Serre, V.; Moore, D.G.; et al. A Mitochondrial Origin for Frontotemporal Dementia and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis through CHCHD10 Involvement. Brain 2014, 137, 2329–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirulli, E.T.; Lasseigne, B.N.; Petrovski, S.; Sapp, P.C.; Dion, P.A.; Leblond, C.S.; Couthouis, J.; Lu, Y.-F.; Wang, Q.; Krueger, B.J.; et al. Exome Sequencing in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Identifies Risk Genes and Pathways. Science 2015, 347, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenna, K.P.; van Doormaal, P.T.C.; Dekker, A.M.; Ticozzi, N.; Kenna, B.J.; Diekstra, F.P.; van Rheenen, W.; van Eijk, K.R.; Jones, A.R.; Keagle, P.; et al. NEK1 Variants Confer Susceptibility to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.L.; Topp, S.; Yang, S.; Smith, B.; Fifita, J.A.; Warraich, S.T.; Zhang, K.Y.; Farrawell, N.; Vance, C.; Hu, X.; et al. CCNF Mutations in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, A.; Kenna, K.P.; Renton, A.E.; Ticozzi, N.; Faghri, F.; Chia, R.; Dominov, J.A.; Kenna, B.J.; Nalls, M.A.; Keagle, P.; et al. Genome-Wide Analyses Identify KIF5A as a Novel ALS Gene. Neuron 2018, 97, 1267–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.; Yilmaz, R.; Müller, K.; Grehl, T.; Petri, S.; Meyer, T.; Grosskreutz, J.; Weydt, P.; Ruf, W.; Neuwirth, C.; et al. Hot-Spot KIF5A Mutations Cause Familial ALS. Brain 2018, 141, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Akiyama, H.; Ikeda, K.; Nonaka, T.; Mori, H.; Mann, D.; Tsuchiya, K.; Yoshida, M.; Hashizume, Y.; et al. TDP-43 Is a Component of Ubiquitin-Positive Tau-Negative Inclusions in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 351, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziortzouda, P.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Hirth, F. Triad of TDP43 Control in Neurodegeneration: Autoregulation, Localization and Aggregation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejzini, R.; Flynn, L.L.; Pitout, I.L.; Fletcher, S.; Wilton, S.D.; Akkari, P.A. ALS Genetics, Mechanisms, and Therapeutics: Where Are We Now? Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanashi, K.; Yamaguchi, A. Aggregation of ALS-Linked FUS Mutant Sequesters RNA Binding Proteins and Impairs RNA Granules Formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 452, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scekic-Zahirovic, J.; Sendscheid, O.; El Oussini, H.; Jambeau, M.; Sun, Y.; Mersmann, S.; Wagner, M.; Dieterlé, S.; Sinniger, J.; Dirrig-Grosch, S.; et al. Toxic Gain of Function from Mutant FUS Protein Is Crucial to Trigger Cell Autonomous Motor Neuron Loss. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 1077–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, K.M.; Glineburg, M.R.; Kearse, M.G.; Flores, B.N.; Linsalata, A.E.; Fedak, S.J.; Goldstrohm, A.C.; Barmada, S.J.; Todd, P.K. RAN Translation at C9orf72-Associated Repeat Expansions Is Selectively Enhanced by the Integrated Stress Response. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensimon, G.; Lacomblez, L.; Meininger, V. A Controlled Trial of Riluzole in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Writing Group; Edaravone (MCI-186) ALS 19 Study Group. Safety and Efficacy of Edaravone in Well Defined Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 505–512. [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.M.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Genge, A.; Shaw, P.J.; Sobue, G.; Bucelli, R.C.; Chiò, A.; Van Damme, P.; Ludolph, A.C.; Glass, J.D.; et al. Trial of Antisense Oligonucleotide Tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; McCoy-Gross, K.; Malcolm, A.; Oranski, J.; Markway, J.W.; Miller, T.M.; Bucelli, R.C. Tofersen Treatment Leads to Sustained Stabilization of Disease in SOD1 ALS in a “Real-World” Setting. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2025, 12, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hu, K.; Smuga-Otto, K.; Tian, S.; Stewart, R.; Slukvin, I.I.; Thomson, J.A. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Free of Vector and Transgene Sequences. Science 2009, 324, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaki, N.; Ban, H.; Nishiyama, A.; Saeki, K.; Hasegawa, M. Efficient Induction of Transgene-Free Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Using a Vector Based on Sendai Virus, an RNA Virus That Does Not Integrate into the Host Genome. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2009, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, H.; Nishishita, N.; Fusaki, N.; Tabata, T.; Saeki, K.; Shikamura, M.; Takada, N.; Inoue, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Kawamata, S.; et al. Efficient Generation of Transgene-Free Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) by Temperature-Sensitive Sendai Virus Vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14234–14239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, L.; Manos, P.D.; Ahfeldt, T.; Loh, Y.-H.; Li, H.; Lau, F.; Ebina, W.; Mandal, P.K.; Smith, Z.D.; Meissner, A.; et al. Highly Efficient Reprogramming to Pluripotency and Directed Differentiation of Human Cells with Synthetic Modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 7, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, N.; Gros, E.; Li, H.-R.; Kumar, S.; Deacon, D.C.; Maron, C.; Muotri, A.R.; Chi, N.C.; Fu, X.-D.; Yu, B.D.; et al. Efficient Generation of Human iPSCs by a Synthetic Self-Replicative RNA. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimos, J.T.; Rodolfa, K.T.; Niakan, K.K.; Weisenthal, L.M.; Mitsumoto, H.; Chung, W.; Croft, G.F.; Saphier, G.; Leibel, R.; Goland, R.; et al. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Generated from Patients with ALS Can Be Differentiated into Motor Neurons. Science 2008, 321, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, E.; Vahsen, B.F.; Calder, E.L.; Xu, Y.; Scaber, J.; Gray, E.; Dafinca, R.; Talbot, K.; Studer, L. Human Stem Cell Models of Neurodegeneration: From Basic Science of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis to Clinical Translation. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, S.M.; Fasano, C.A.; Papapetrou, E.P.; Tomishima, M.; Sadelain, M.; Studer, L. Highly Efficient Neural Conversion of Human ES and iPS Cells by Dual Inhibition of SMAD Signaling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Dalton, S.; Stice, S.L. Human Motor Neuron Differentiation from Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2005, 14, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osaki, T.; Uzel, S.G.M.; Kamm, R.D. Microphysiological 3D Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) from Human iPS-Derived Muscle Cells and Optogenetic Motor Neurons. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, J.D.; DuBreuil, D.M.; Devlin, A.-C.; Held, A.; Sapir, Y.; Berezovski, E.; Hawrot, J.; Dorfman, K.; Chander, V.; Wainger, B.J. Human Sensorimotor Organoids Derived from Healthy and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Stem Cells Form Neuromuscular Junctions. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Shi, Q.; Pan, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lang, J.; Wen, S.; Liu, X.; Cheng, T.-L.; Lei, K. Neuromuscular Organoids Model Spinal Neuromuscular Pathologies in C9orf72 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.; Cermak, T.; Doyle, E.L.; Schmidt, C.; Zhang, F.; Hummel, A.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Voytas, D.F. Targeting DNA Double-Strand Breaks with TAL Effector Nucleases. Genetics 2010, 186, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable Dual RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiskinis, E.; Sandoe, J.; Williams, L.A.; Boulting, G.L.; Moccia, R.; Wainger, B.J.; Han, S.; Peng, T.; Thams, S.; Mikkilineni, S.; et al. Pathways Disrupted in Human ALS Motor Neurons Identified through Genetic Correction of Mutant SOD1. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, L.; Gao, Q.; Yu, D.; Sun, M. CRISPR/Cas9: Implication for Modeling and Therapy of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1223777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainger, B.J.; Kiskinis, E.; Mellin, C.; Wiskow, O.; Han, S.S.W.; Sandoe, J.; Perez, N.P.; Williams, L.A.; Lee, S.; Boulting, G.; et al. Intrinsic Membrane Hyperexcitability of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patient-Derived Motor Neurons. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setsu, S.; Morimoto, S.; Nakamura, S.; Ozawa, F.; Utami, K.H.; Nishiyama, A.; Suzuki, N.; Aoki, M.; Takeshita, Y.; Tomari, Y.; et al. Swift Induction of Human Spinal Lower Motor Neurons and Robust ALS Cell Screening via Single-Cell Imaging. Stem Cell Rep. 2025, 20, 102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szebényi, K.; Wenger, L.M.D.; Sun, Y.; Dunn, A.W.E.; Limegrover, C.A.; Gibbons, G.M.; Conci, E.; Paulsen, O.; Mierau, S.B.; Balmus, G.; et al. Human ALS/FTD Brain Organoid Slice Cultures Display Distinct Early Astrocyte and Targetable Neuronal Pathology. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.M.; Blurton-Jones, M.; Rhee, S.W.; Cribbs, D.H.; Cotman, C.W.; Jeon, N.L. A Microfluidic Culture Platform for CNS Axonal Injury, Regeneration and Transport. Nat. Methods 2005, 2, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.M.; Dieterich, D.C.; Ito, H.T.; Kim, S.A.; Schuman, E.M. Microfluidic Local Perfusion Chambers for the Visualization and Manipulation of Synapses. Neuron 2010, 66, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, P.M.; Willaime-Morawek, S.; Siow, R.; Barber, M.; Owens, R.M.; Sharma, A.D.; Rowan, W.; Hill, E.; Zagnoni, M. Advances in Microfluidic in Vitro Systems for Neurological Disease Modeling. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 99, 1276–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jongh, R.; Spijkers, X.M.; Pasteuning-Vuhman, S.; Vulto, P.; Pasterkamp, R.J. Neuromuscular Junction-on-a-Chip: ALS Disease Modeling and Read-out Development in Microfluidic Devices. J. Neurochem. 2021, 157, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, K.; Yada, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Morita, M.; Kawata, A.; Arisato, T.; Nagahashi, A.; Enami, T.; Tsukita, K.; Kawakami, H.; et al. Prediction Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis by Deep Learning with Patient Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 89, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornauer, P.; Prack, G.; Anastasi, N.; Ronchi, S.; Kim, T.; Donner, C.; Fiscella, M.; Borgwardt, K.; Taylor, V.; Jagasia, R.; et al. DeePhys: A Machine Learning–Assisted Platform for Electrophysiological Phenotyping of Human Neuronal Networks. Stem Cell Rep. 2024, 19, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, C.; Ueda, K.; Morimoto, S.; Takahashi, S.; Nakamura, S.; Ozawa, F.; Ito, D.; Daté, Y.; Okada, K.; Kobayashi, N.; et al. Proteomic Insights into Extracellular Vesicles in ALS for Therapeutic Potential of Ropinirole and Biomarker Discovery. Inflamm. Regen. 2024, 44, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The NeuroLINCS Consortium; Li, J.; Lim, R.G.; Kaye, J.A.; Dardov, V.; Coyne, A.N.; Wu, J.; Milani, P.; Cheng, A.; Thompson, T.G.; et al. An Integrated Multi-Omic Analysis of iPSC-Derived Motor Neurons from C9ORF72 ALS Patients. iScience 2021, 24, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, E.B.; de Winter, F.; Verhaagen, J. ALS as a Distal Axonopathy: Molecular Mechanisms Affecting Neuromuscular Junction Stability in the Presymptomatic Stages of the Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadon-Nachum, M.; Melamed, E.; Offen, D. The “Dying-Back” Phenomenon of Motor Neurons in ALS. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2011, 43, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hörner, S.J.; Couturier, N.; Hafner, M.; Rudolf, R. Schwann Cells in Neuromuscular In Vitro Models. Biol. Chem. 2024, 405, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.; Revah, O.; Miura, Y.; Thom, N.; Amin, N.D.; Kelley, K.W.; Singh, M.; Chen, X.; Thete, M.V.; Walczak, E.M.; et al. Generation of Functional Human 3D Cortico-Motor Assembloids. Cell 2020, 183, 1913–1929.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, M.F.; Martinez, F.J.; Wright, S.; Ramos, C.; Volfson, D.; Mason, M.; Garnes, J.; Dang, V.; Lievers, J.; Shoukat-Mumtaz, U.; et al. A Cellular Model for Sporadic ALS Using Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 56, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Song, J.; Huang, H.; Chen, H.; Qian, K. Modeling Hallmark Pathology Using Motor Neurons Derived from the Family and Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patient-Specific iPS Cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.J.; Dariolli, R.; Jorge, F.M.; Monteiro, M.R.; Maximino, J.R.; Martins, R.S.; Strauss, B.E.; Krieger, J.E.; Callegaro, D.; Chadi, G. Gene Expression Profiling for Human iPS-Derived Motor Neurons from Sporadic ALS Patients Reveals a Strong Association between Mitochondrial Functions and Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2015, 9, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Liu, M.; Sánchez, Y.F.; Avazzadeh, S.; Quinlan, L.R.; Liu, G.; Lu, Y.; Yang, G.; O’Brien, T.; Henshall, D.C.; et al. A Novel Protocol to Derive Cervical Motor Neurons from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Stem Cell Rep. 2023, 18, 1870–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, K.; Huang, H.; Peterson, A.; Hu, B.; Maragakis, N.J.; Ming, G.-L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, S.-C. Sporadic ALS Astrocytes Induce Neuronal Degeneration In Vivo. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 8, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Dittlau, K.S.; Sicart, A.; Janky, R.; Van Damme, P.; Van Den Bosch, L. Sporadic ALS hiPSC-Derived Motor Neurons Show Axonal Defects Linked to Altered Axon Guidance Pathways. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 206, 106815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Otomo, A.; Atsuta, N.; Nakamura, R.; Akiyama, T.; Hadano, S.; Aoki, M.; Saya, H.; Sobue, G.; et al. Modeling Sporadic ALS in iPSC-Derived Motor Neurons Identifies a Potential Therapeutic Agent. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxi, E.G.; Thompson, T.; Li, J.; Kaye, J.A.; Lim, R.G.; Wu, J.; Ramamoorthy, D.; Lima, L.; Vaibhav, V.; Matlock, A.; et al. Answer ALS, a Large-Scale Resource for Sporadic and Familial ALS Combining Clinical and Multi-Omics Data from Induced Pluripotent Cell Lines. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, S.; Takahashi, S.; Ito, D.; Daté, Y.; Okada, K.; Kato, C.; Nakamura, S.; Ozawa, F.; Chyi, C.M.; Nishiyama, A.; et al. Phase 1/2a Clinical Trial in ALS with Ropinirole, a Drug Candidate Identified by iPSC Drug Discovery. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 766–780.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M.J.; Lim, R.G.; Wu, J.; Frank, A.; Ornelas, L.; Panther, L.; Galvez, E.; Perez, D.; Meepe, I.; Lei, S.; et al. Large-Scale Differentiation of iPSC-Derived Motor Neurons from ALS and Control Subjects. Neuron 2023, 111, 1191–1204.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitkov, S.; Valentine, K.; Kozareva, V.; Donde, A.; Frank, A.; Lei, S.; Van Eyk, J.E.; Finkbeiner, S.; Rothstein, J.D.; Thompson, L.M.; et al. Disease Related Changes in ATAC-Seq of iPSC-Derived Motor Neuron Lines from ALS Patients and Controls. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, J.D.; Keeley, O.; Warlick, C.; Miller, T.M.; Ly, C.V.; Glass, J.D.; Coyne, A.N. Sporadic ALS Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Derived Neurons Reveal Hallmarks of TDP-43 Loss of Function. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bye, C.R.; Qian, E.; Lim, K.; Daniszewski, M.; Garton, F.C.; Trần-Lê, B.C.; Liang, H.H.; Lin, T.; Lock, J.G.; Crombie, D.E.; et al. Large-Scale Drug Screening in iPSC-Derived Motor Neurons from Sporadic ALS Patients Identifies a Potential Combinatorial Therapy. Nat. Neurosci. 2025, 29, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lall, D.; Workman, M.J.; Sances, S.; Ondatje, B.N.; Bell, S.; Lawless, G.; Woodbury, A.; West, D.; Meyer, A.; Matlock, A.; et al. An Organ-Chip Model of Sporadic ALS Using iPSC-Derived Spinal Cord Motor Neurons and an Integrated Blood-Brain-like Barrier. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 1139–1153.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainger, B.J.; Macklin, E.A.; Vucic, S.; McIlduff, C.E.; Paganoni, S.; Maragakis, N.J.; Bedlack, R.; Goyal, N.A.; Rutkove, S.B.; Lange, D.J.; et al. Effect of Ezogabine on Cortical and Spinal Motor Neuron Excitability in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickel, N.; Hewett, K.; Rayner, K.; McDonald, S.; De’Ath, J.; Daniluk, J.; Joshi, K.; Boll, M.C.; Tiamkao, S.; Vorobyeva, O.; et al. Safety of Retigabine in Adults with Partial-Onset Seizures after Long-Term Exposure: Focus on Unexpected Ophthalmological and Dermatological Events. Epilepsy Behav. 2020, 102, 106580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, K.; Izumi, Y.; Watanabe, A.; Tsukita, K.; Woltjen, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Hotta, A.; Kondo, T.; Kitaoka, S.; Ohta, A.; et al. The Src/c-Abl Pathway Is a Potential Therapeutic Target in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaaf3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, K.; Izumi, Y.; Nagai, M.; Nishiyama, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Hanajima, R.; Egawa, N.; Ayaki, T.; Oki, R.; Fujita, K.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of Bosutinib in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (iDReAM Study): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Dose-Escalation Phase 1 Trial. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 53, 101707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, D.; O’Rourke, J.G.; Meera, P.; Muhammad, A.K.M.G.; Grant, S.; Simpkinson, M.; Bell, S.; Carmona, S.; Ornelas, L.; Sahabian, A.; et al. Targeting RNA Foci in iPSC-Derived Motor Neurons from ALS Patients with a C9ORF72 Repeat Expansion. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 208ra149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, L.H.; Rothstein, J.D.; Shaw, P.J.; Babu, S.; Benatar, M.; Bucelli, R.C.; Genge, A.; Glass, J.D.; Hardiman, O.; Libri, V.; et al. Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Antisense Oligonucleotide BIIB078 in Adults with C9orf72-Associated Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Phase 1, Randomised, Double Blinded, Placebo-Controlled, Multiple Ascending Dose Study. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Andreucci, A.; Iwamoto, N.; Yin, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, F.; Bulychev, A.; Hu, X.S.; Lin, X.; Lamore, S.; et al. Preclinical Evaluation of WVE-004, Aninvestigational Stereopure Oligonucleotide Forthe Treatment of C9orf72-Associated ALS or FTD. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 28, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, C.J.; Zhang, P.-W.; Pham, J.T.; Haeusler, A.R.; Mistry, N.A.; Vidensky, S.; Daley, E.L.; Poth, E.M.; Hoover, B.; Fines, D.M.; et al. RNA Toxicity from the ALS/FTD C9ORF72 Expansion Is Mitigated by Antisense Intervention. Neuron 2013, 80, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganoni, S.; Macklin, E.A.; Hendrix, S.; Berry, J.D.; Elliott, M.A.; Maiser, S.; Karam, C.; Caress, J.B.; Owegi, M.A.; Quick, A.; et al. Trial of Sodium Phenylbutyrate-Taurursodiol for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, H.; Morimoto, S.; Kato, C.; Nakahara, J.; Takahashi, S. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells-Based Disease Modeling, Drug Screening, Clinical Trials, and Reverse Translational Research for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 2023, 167, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapasset, L.; Milhavet, O.; Prieur, A.; Besnard, E.; Babled, A.; Aït-Hamou, N.; Leschik, J.; Pellestor, F.; Ramirez, J.-M.; De Vos, J.; et al. Rejuvenating Senescent and Centenarian Human Cells by Reprogramming through the Pluripotent State. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 2248–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, J.; Paquola, A.C.M.; Ku, M.; Hatch, E.; Böhnke, L.; Ladjevardi, S.; McGrath, S.; Campbell, B.; Lee, H.; Herdy, J.R.; et al. Directly Reprogrammed Human Neurons Retain Aging-Associated Transcriptomic Signatures and Reveal Age-Related Nucleocytoplasmic Defects. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierbuchen, T.; Ostermeier, A.; Pang, Z.P.; Kokubu, Y.; Südhof, T.C.; Wernig, M. Direct Conversion of Fibroblasts to Functional Neurons by Defined Factors. Nature 2010, 463, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.D.; Ganat, Y.M.; Kishinevsky, S.; Bowman, R.L.; Liu, B.; Tu, E.Y.; Mandal, P.K.; Vera, E.; Shim, J.; Kriks, S.; et al. Human iPSC-Based Modeling of Late-Onset Disease via Progerin-Induced Aging. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera, E.; Bosco, N.; Studer, L. Generating Late-Onset Human iPSC-Based Disease Models by Inducing Neuronal Age-Related Phenotypes through Telomerase Manipulation. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempthorne, L.; Vaizoglu, D.; Cammack, A.J.; Carcolé, M.; Roberts, M.J.; Mikheenko, A.; Fisher, A.; Suklai, P.; Muralidharan, B.; Kroll, F.; et al. Dual-Targeting CRISPR-CasRx Reduces C9orf72 ALS/FTD Sense and Antisense Repeat RNAs in Vitro and in Vivo. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, J.D.; Baskerville, V.; Rapuri, S.; Mehlhop, E.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Rigo, F.; Bennett, F.; Mizielinska, S.; Isaacs, A.; Coyne, A.N. G2C4 Targeting Antisense Oligonucleotides Potently Mitigate TDP-43 Dysfunction in Human C9orf72 ALS/FTD Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Derived Neurons. Acta Neuropathol. 2023, 147, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatar, M.; Wuu, J.; Andersen, P.M.; Bucelli, R.C.; Andrews, J.A.; Otto, M.; Farahany, N.A.; Harrington, E.A.; Chen, W.; Mitchell, A.A.; et al. Design of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial of Tofersen Initiated in Clinically Presymptomatic SOD1 Variant Carriers: The ATLAS Study. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Brothwood, J.L.; Saini, H.; O’Sullivan, G.A.; Bento, C.F.; McCarthy, J.M.; Wallis, N.G.; Di Daniel, E.; Graham, B.; Tams, D.M. Altered Inflammatory Signature in a C9ORF72-ALS iPSC-Derived Motor Neuron and Microglia Coculture Model. Glia 2026, 74, e70084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahsen, B.F.; Nalluru, S.; Morgan, G.R.; Farrimond, L.; Carroll, E.; Xu, Y.; Cramb, K.M.L.; Amein, B.; Scaber, J.; Katsikoudi, A.; et al. C9orf72-ALS Human iPSC Microglia Are pro-Inflammatory and Toxic to Co-Cultured Motor Neurons via MMP9. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonustun, B.; Vahsen, B.F.; Ledesma-Terrón, M.; Li, Z.; Tuffery, L.; Xu, N.; Calder, E.L.; Jungverdorben, J.; Weber, L.; Zhong, A.; et al. Telmisartan Is Neuroprotective in a hiPSC-Derived Spinal Microtissue Model for C9orf72 ALS via Inhibition of Neuroinflammation. Stem Cell Rep. 2025, 20, 102535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Salamotas, I.; Stavropoulou De Lorenzo, S.; Stachtiari, A.; Taxiarchis, A.; Tsolaki, M.; Michailidou, I.; Preza, E. From Dish to Trial: Building Translational Models of ALS. Cells 2026, 15, 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030247

Salamotas I, Stavropoulou De Lorenzo S, Stachtiari A, Taxiarchis A, Tsolaki M, Michailidou I, Preza E. From Dish to Trial: Building Translational Models of ALS. Cells. 2026; 15(3):247. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030247

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalamotas, Ilias, Sotiria Stavropoulou De Lorenzo, Aggeliki Stachtiari, Apostolos Taxiarchis, Magda Tsolaki, Iliana Michailidou, and Elisavet Preza. 2026. "From Dish to Trial: Building Translational Models of ALS" Cells 15, no. 3: 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030247

APA StyleSalamotas, I., Stavropoulou De Lorenzo, S., Stachtiari, A., Taxiarchis, A., Tsolaki, M., Michailidou, I., & Preza, E. (2026). From Dish to Trial: Building Translational Models of ALS. Cells, 15(3), 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030247