Post-Translational Modifications in HIV Infection: Novel Antiretroviral Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

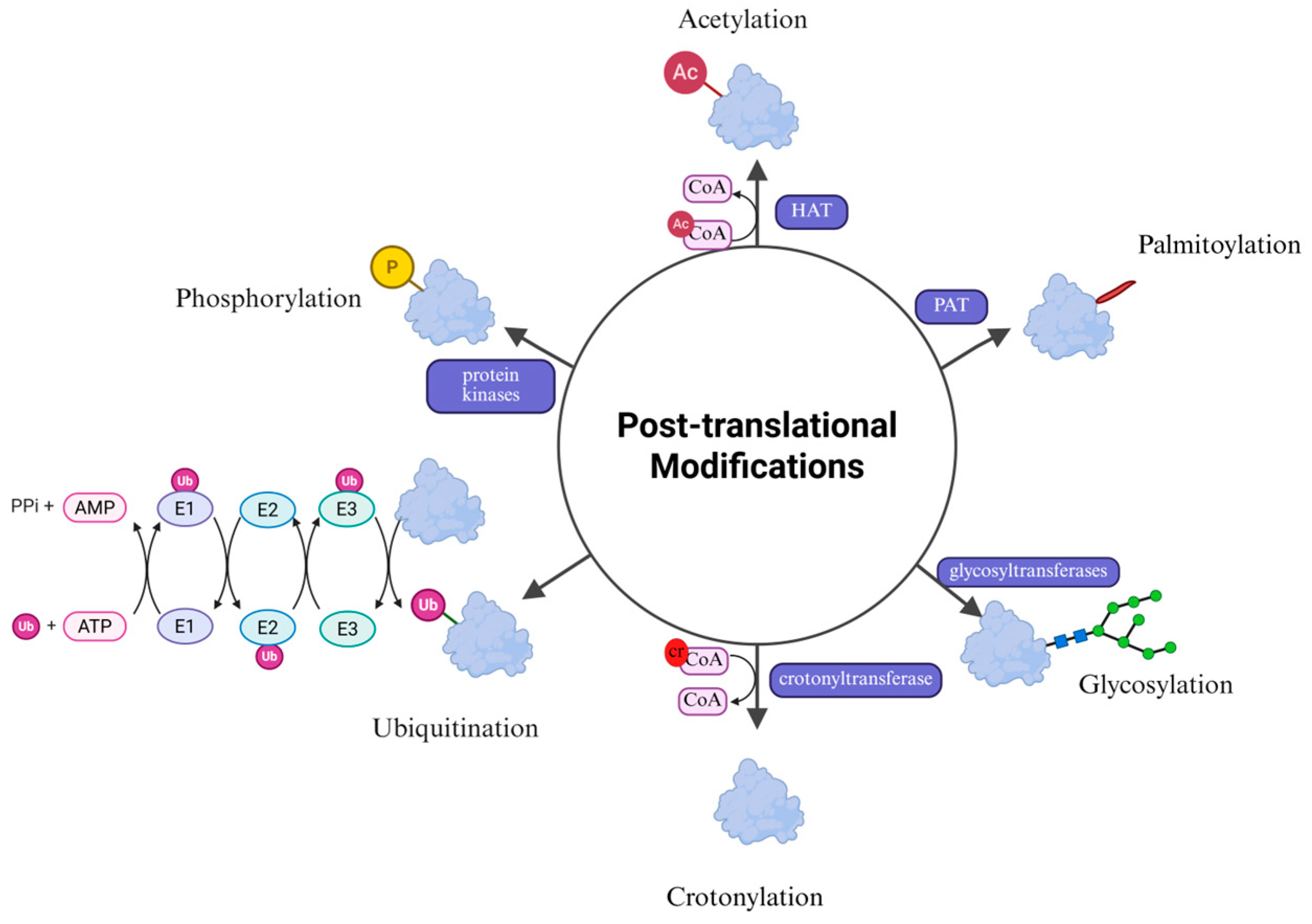

2. PTMs and HIV

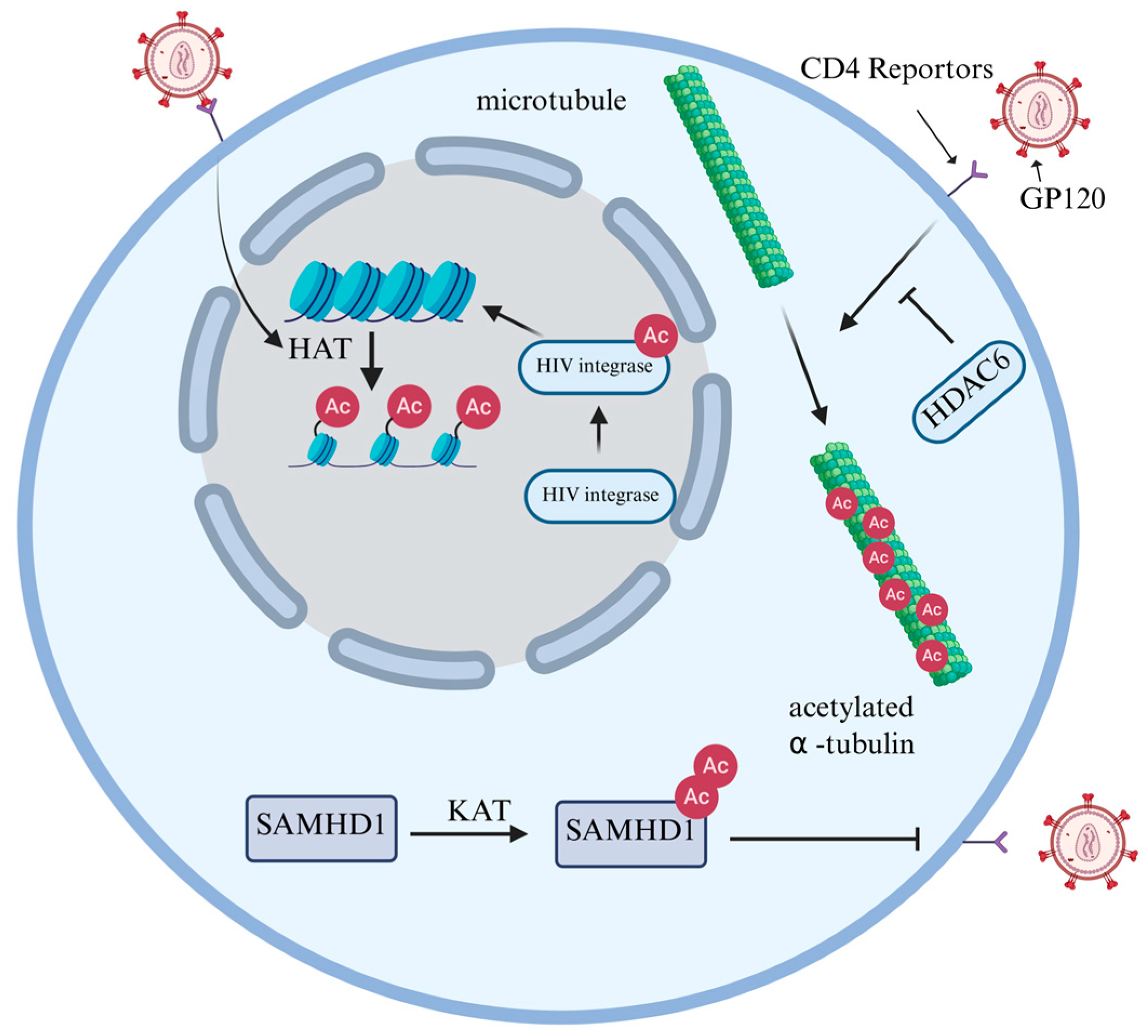

2.1. Acetylation

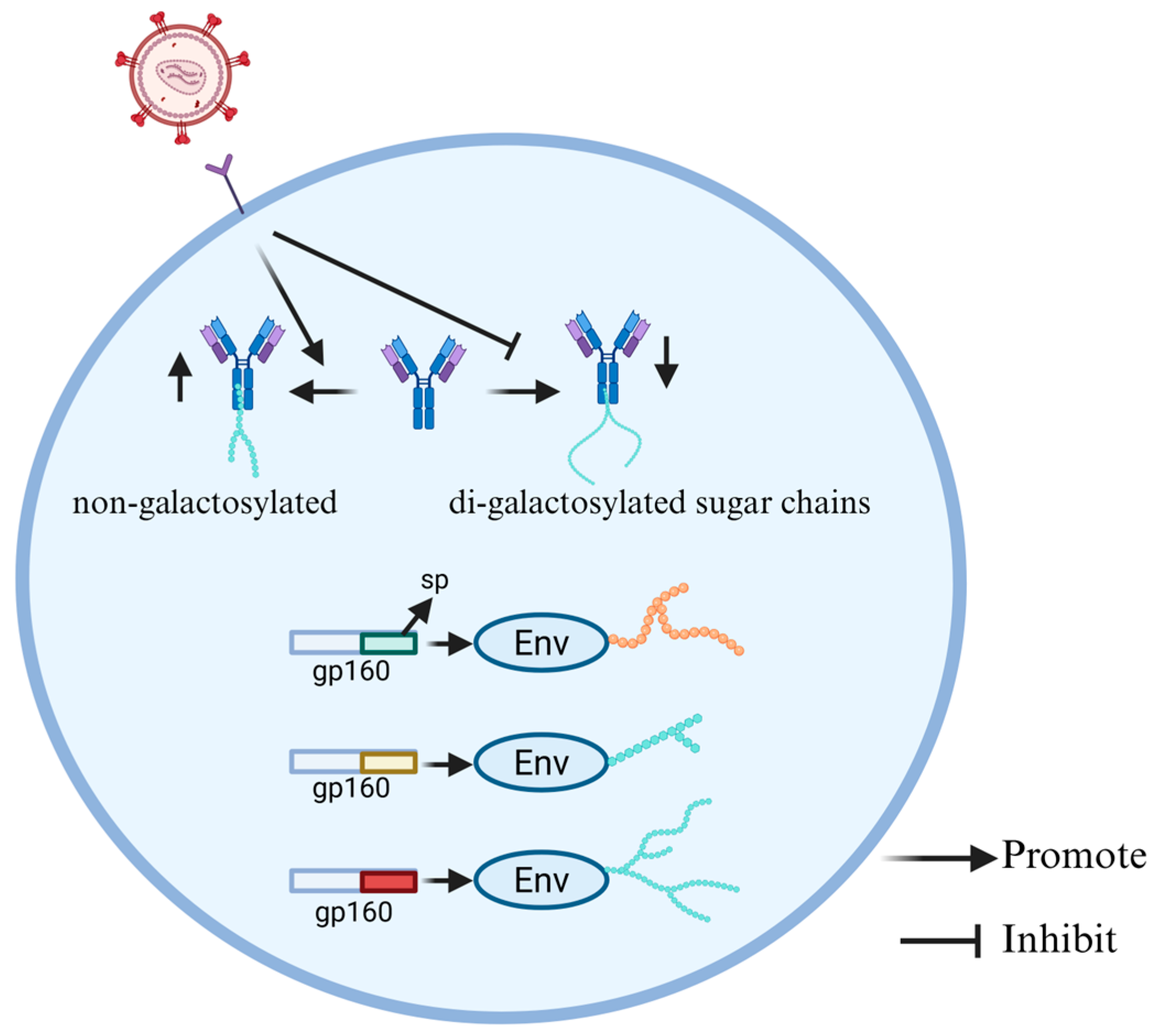

2.2. Glycosylation

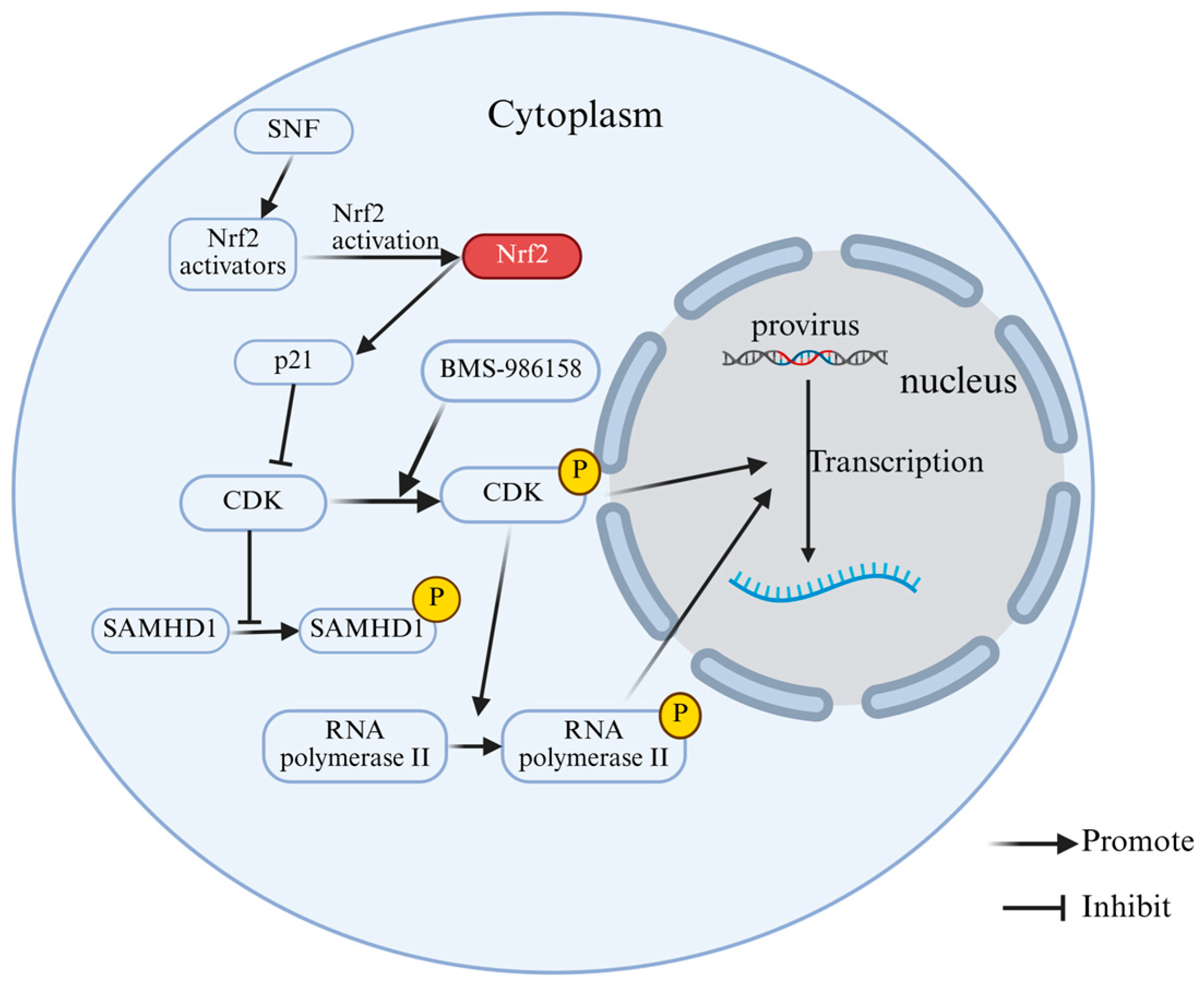

2.3. Phosphorylation

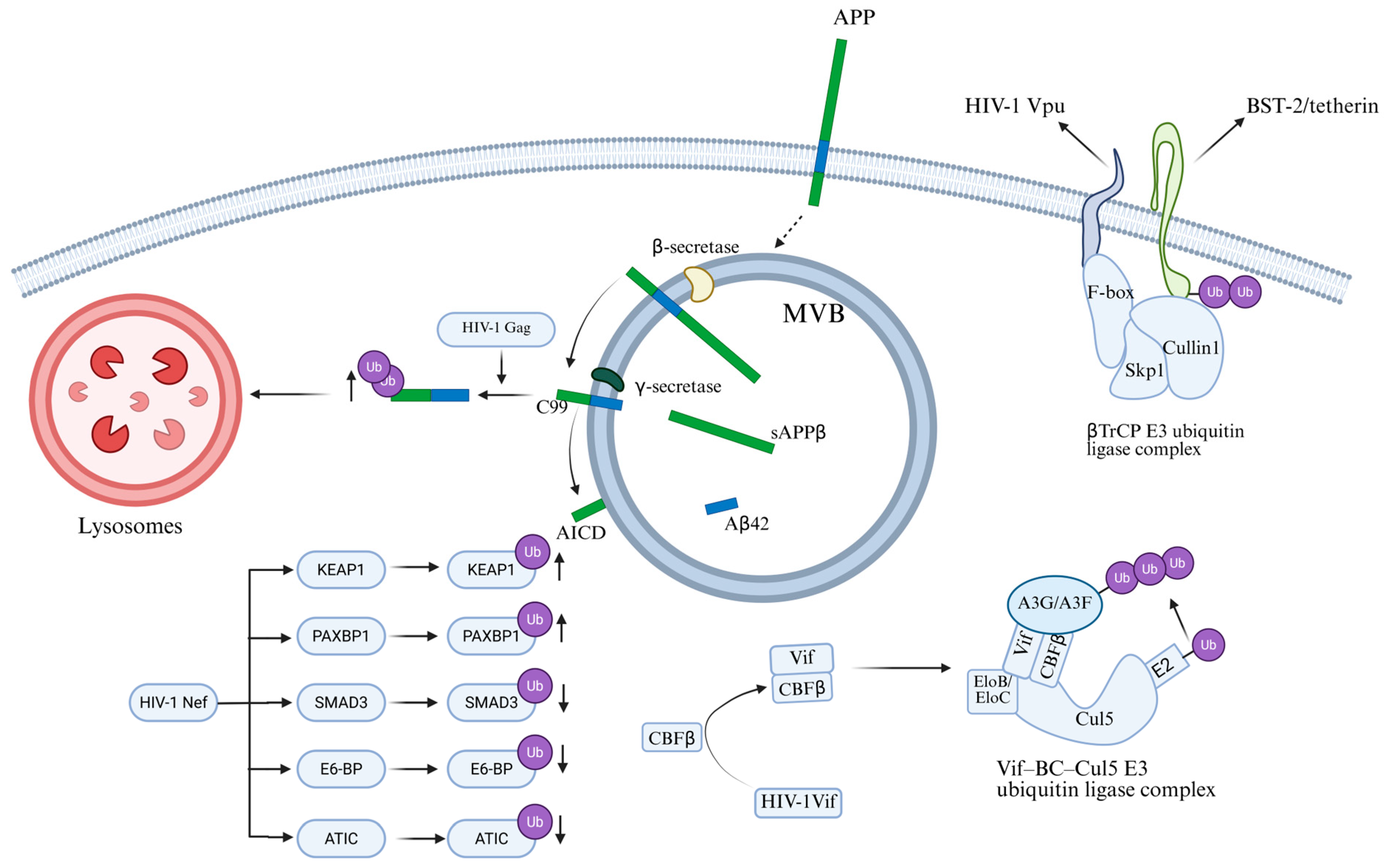

2.4. Ubiquitination

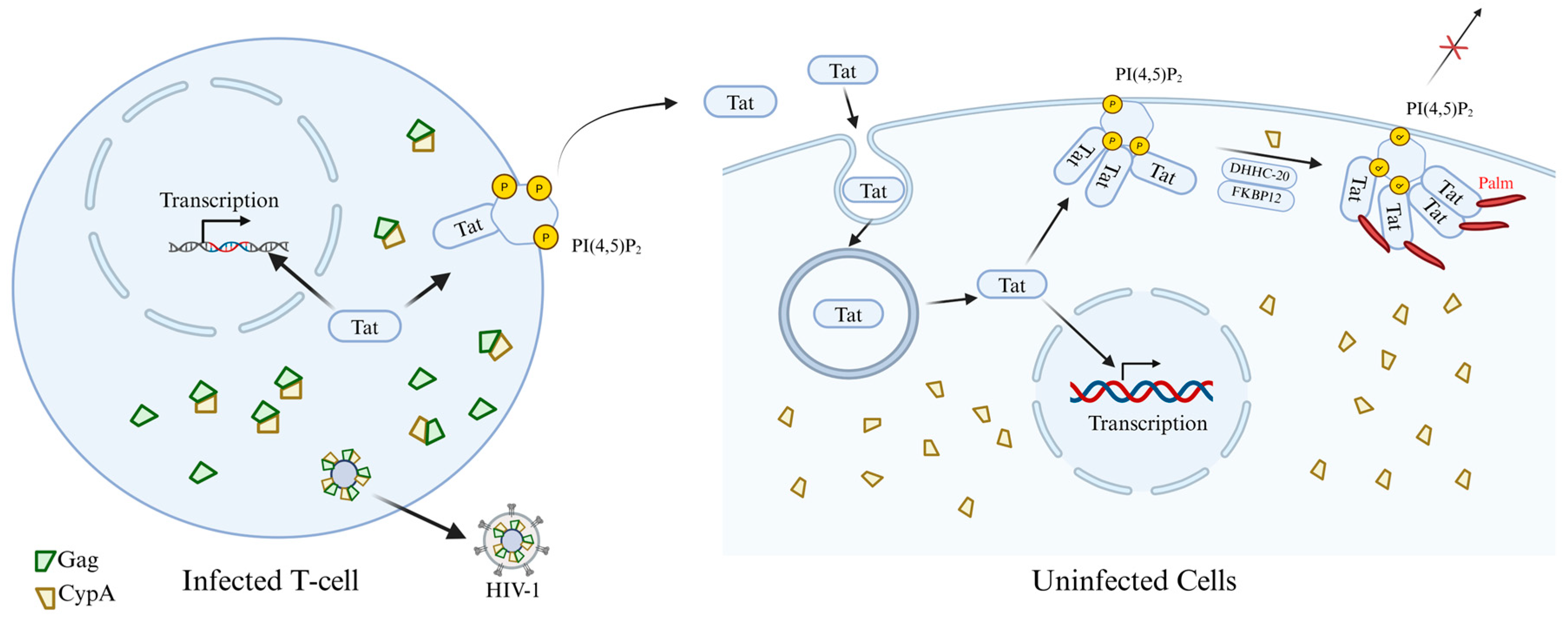

2.5. Palmitoylation

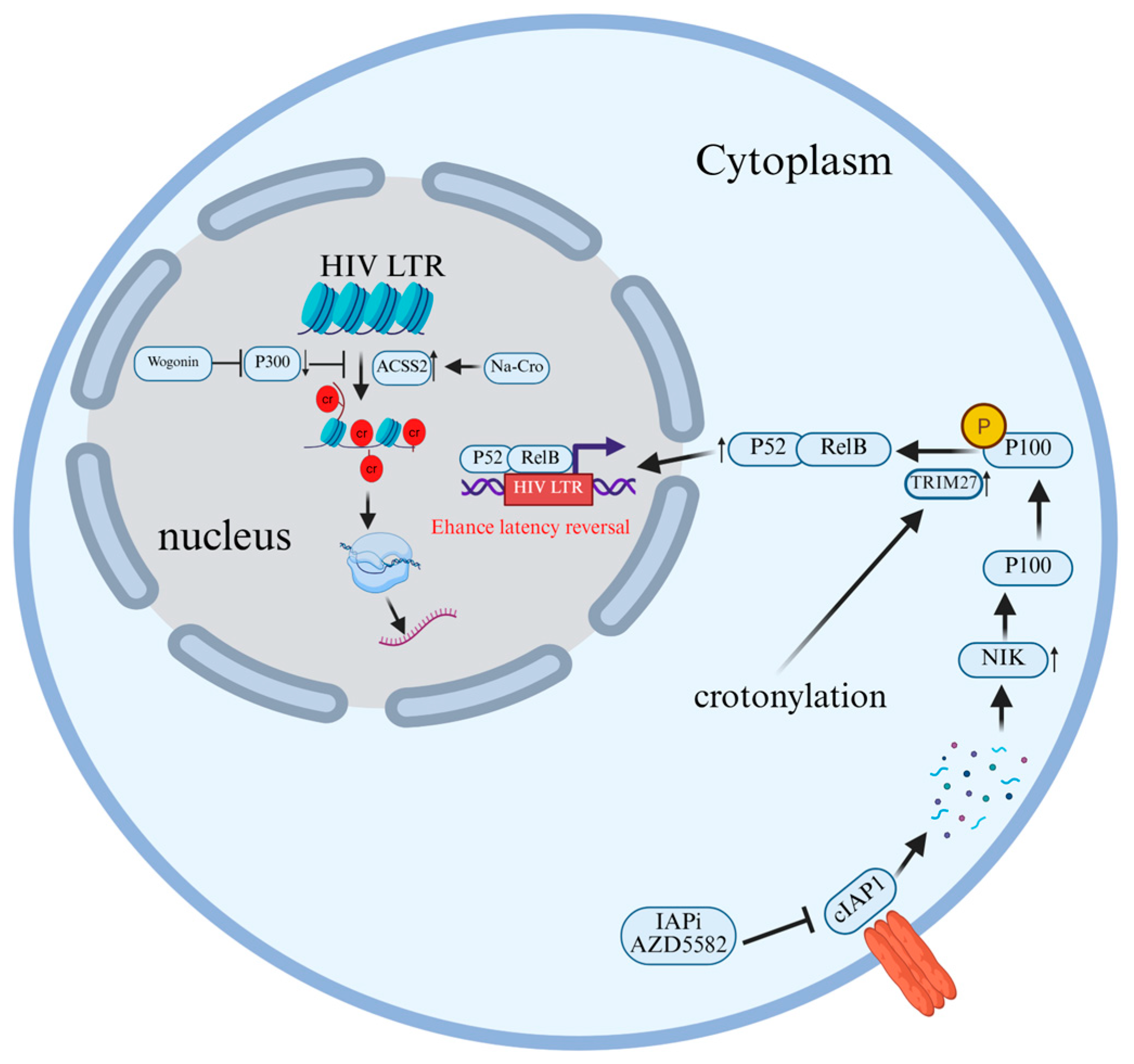

2.6. Crotonylation

3. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masenga, S.K.; Mweene, B.C.; Luwaya, E.; Muchaili, L.; Chona, M.; Kirabo, A. HIV-Host Cell Interactions. Cells 2023, 12, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.C.; Maggirwar, N.S.; Marsden, M.D. HIV Persistence, Latency, and Cure Approaches: Where Are We Now? Viruses 2024, 16, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Langer, S.; Zhang, Z.; Herbert, K.M.; Yoh, S.; König, R.; Chanda, S.K. Sensor Sensibility-HIV-1 and the Innate Immune Response. Cells 2020, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, S.; Chen, H.; Chen, D.; Li, C.; Li, W. The reservoir of latent HIV. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 945956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, L.B.; Chomont, N.; Deeks, S.G. The Biology of the HIV-1 Latent Reservoir and Implications for Cure Strategies. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Advisory Committee Blood (Arbeitskreis Blut), Subgroup ‘Assessment of Pathogens Transmissible by Blood’. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2016, 43, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwagaba, J.; Li, J.A.; Ngo, B.; Sutton, R.E. 30 years of HIV therapy: Current and future antiviral drug targets. Virology 2025, 603, 110362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, K.O.; Counts, J.; Thakur, B.; Stalls, V.; Edwards, R.; Manne, K.; Lu, X.; Mansouri, K.; Chen, Y.; Parks, R.; et al. Vaccine induction of CD4-mimicking HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in macaques. Cell 2024, 187, 79–94.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Cai, Y.; Chen, B. HIV-1 Entry and Membrane Fusion Inhibitors. Viruses 2021, 13, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negi, G.; Sharma, A.; Dey, M.; Dhanawat, G.; Parveen, N. Membrane attachment and fusion of HIV-1, influenza A, and SARS-CoV-2: Resolving the mechanisms with biophysical methods. Biophys. Rev. 2022, 14, 1109–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapp, N.; Burge, N.; Cox, K.; Prakash, P.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Thapa, S.; Christensen, D.; Li, M.; Linderberger, J.; Kvaratskhelia, M.; et al. HIV-1 Preintegration Complex Preferentially Integrates the Viral DNA into Nucleosomes Containing Trimethylated Histone 3-Lysine 36 Modification and Flanking Linker DNA. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0101122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Rodriguez, G.; Gazi, A.; Monel, B.; Frabetti, S.; Scoca, V.; Mueller, F.; Schwartz, O.; Krijnse-Locker, J.; Charneau, P.; Di Nunzio, F. Remodeling of the Core Leads HIV-1 Preintegration Complex into the Nucleus of Human Lymphocytes. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozina, A.; Anisenko, A.; Kikhai, T.; Silkina, M.; Gottikh, M. Complex Relationships between HIV-1 Integrase and Its Cellular Partners. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.L.; Kutluay, S.B. Going beyond Integration: The Emerging Role of HIV-1 Integrase in Virion Morphogenesis. Viruses 2020, 12, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, E.O. HIV-1 assembly, release and maturation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, A.; Freed, E.O. Cell-type-dependent targeting of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly to the plasma membrane and the multivesicular body. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 1552–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, T.R.; Yoo, S.; Vajdos, F.F.; von Schwedler, U.K.; Worthylake, D.K.; Wang, H.; McCutcheon, J.P.; Sundquist, W.I.; Hill, C.P. Structure of the carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 1997, 278, 849–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinpeter, A.B.; Freed, E.O. HIV-1 Maturation: Lessons Learned from Inhibitors. Viruses 2020, 12, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, C.S.; Freed, E.O. Novel approaches to inhibiting HIV-1 replication. Antivir. Res. 2010, 85, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Keppler, O.T.; Schölz, C. Post-translational Modification-Based Regulation of HIV Replication. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Kim, M.; Soper, A.; Kovarova, M.; Spagnuolo, R.A.; Begum, N.; Kirchherr, J.; Archin, N.; Battaglia, D.; Cleveland, D.; et al. Analysis of the effect of HDAC inhibitors on the formation of the HIV reservoir. mBio 2024, 15, e0163224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibebe, H.; Marquez, D.; McGraw, A.; Gagliardi, S.; Sullivan, C.; Hillmer, G.; Narayan, K.; Izumi, C.; Keating, A.; Izumi, T. Targeting Latent HIV Reservoirs: Effectiveness of Combination Therapy with HDAC and PARP Inhibitors. Viruses 2025, 17, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Hei, H. Advances in post-translational modifications of proteins and cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1229397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, G. Protein Modification and Autophagy Activation. In Autophagy: Biology and Diseases; Qin, Z.H., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1206, pp. 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotenbreg, G.; Ploegh, H. Chemical biology: Dressed-up proteins. Nature 2007, 446, 993–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Sun, Y.; Yu, W. HDACs and Their Inhibitors on Post-Translational Modifications: The Regulation of Cardiovascular Disease. Cells 2025, 14, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, E.K.; Zachman, D.K.; Hirschey, M.D. Discovering the landscape of protein modifications. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 1868–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Huang, H.; Zhan, Q.; Wang, F.; Chen, Z.; Lu, X.; Sun, G. Post-translational modifications in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussienne, C.; Marquet, R.; Paillart, J.C.; Bernacchi, S. Post-Translational Modifications of Retroviral HIV-1 Gag Precursors: An Overview of Their Biological Role. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.R.; Crosby, D.C.; Hultquist, J.F.; Kurland, A.P.; Adhikary, P.; Li, D.; Marlett, J.; Swann, J.; Hüttenhain, R.; Verschueren, E.; et al. Global post-translational modification profiling of HIV-1-infected cells reveals mechanisms of host cellular pathway remodeling. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.; Chen, R. Pathological implication of protein post-translational modifications in cancer. Mol. Asp. Med. 2022, 86, 101097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhang, M.; Guo, C.; Guo, X.; Ma, Y.; Ma, Y. Implication of protein post translational modifications in gastric cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1523958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Feng, T.; Chen, Z.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Dai, J. Protein Acetylation Going Viral: Implications in Antiviral Immunity and Viral Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yuan, Q.; Cao, S.; Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Xia, Y.; Bian, Y.; Xu, F.; Chen, Y. Review: Acetylation mechanisms and targeted therapies in cardiac fibrosis. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 193, 106815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, A.W.; Dhanjal, H.K.; Rossner, B.; Mahmood, H.; Patel, V.I.; Nadim, M.; Lota, M.; Shahid, F.; Li, Z.; Joyce, D.; et al. Acetylation of nuclear receptors in health and disease: An update. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shvedunova, M.; Akhtar, A. Modulation of cellular processes by histone and non-histone protein acetylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabo, Y.; Walsh, D.; Barry, D.S.; Tinaztepe, S.; de Los Santos, K.; Goff, S.P.; Gundersen, G.G.; Naghavi, M.H. HIV-1 induces the formation of stable microtubules to enhance early infection. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Fernández, A.; Alvarez, S.; Gordon-Alonso, M.; Barrero, M.; Ursa, A.; Cabrero, J.R.; Fernández, G.; Naranjo-Suárez, S.; Yáñez-Mo, M.; Serrador, J.M.; et al. Histone deacetylase 6 regulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 5445–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimani, M.; Ahmad, A.; Stacey, S.; Duse, A. Examining the levels of acetylation, DNA methylation and phosphorylation in HIV-1 positive and multidrug-resistant TB-HIV patients. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 23, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, F.; Atkinson, R.; Cook, A.L.; Phipps, A.J.; King, A.E. The role of altered protein acetylation in neurodegenerative disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1025473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstone, D.C.; Ennis-Adeniran, V.; Hedden, J.J.; Groom, H.C.; Rice, G.I.; Christodoulou, E.; Walker, P.A.; Kelly, G.; Haire, L.F.; Yap, M.W.; et al. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature 2011, 480, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, N.E.; Oo, A.; Kim, B. Mechanistic Interplay between HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme Kinetics and Host SAMHD1 Protein: Viral Myeloid-Cell Tropism and Genomic Mutagenesis. Viruses 2022, 14, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulnes-Ramos, A.; Schott, K.; Rabinowitz, J.; Luchsinger, C.; Bertelli, C.; Miyagi, E.; Yu, C.H.; Persaud, M.; Shepard, C.; König, R.; et al. Acetylation of SAMHD1 at lysine 580 is crucial for blocking HIV-1 infection. mBio 2024, 15, e0195824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatham, J.C.; Patel, R.P. Protein glycosylation in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, C.; Zou, Q.; Bai, X.; Shi, W. Effect of glycosylation on protein folding: From biological roles to chemical protein synthesis. iScience 2025, 28, 112605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groux-Degroote, S.; Cavdarli, S.; Uchimura, K.; Allain, F.; Delannoy, P. Glycosylation changes in inflammatory diseases. In Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology; Donev, R., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; Volume 119, pp. 111–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Du, M.; Xin, W. Functioning and mechanisms of PTMs in renal diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1238706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, Y.; Bowden, T.A.; Wilson, I.A.; Crispin, M. Exploitation of glycosylation in enveloped virus pathobiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 1480–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, M.L.; Allen, J.D.; Crispin, M. Influence of glycosylation on the immunogenicity and antigenicity of viral immunogens. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 70, 108283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, K.; Seaman, M.S. Divide and conquer: Broadly neutralizing antibody combinations for improved HIV-1 viral coverage. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2023, 18, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, G.S.; Upadhyay, C. HIV-1 Envelope Glycosylation and the Signal Peptide. Vaccines 2021, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, C.; Feyznezhad, R.; Cao, L.; Chan, K.W.; Liu, K.; Yang, W.; Zhang, H.; Yolitz, J.; Arthos, J.; Nadas, A.; et al. Signal peptide of HIV-1 envelope modulates glycosylation impacting exposure of V1V2 and other epitopes. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1009185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.J.; Gonzalez, J.C.; Ghosh, D.; Mellins, E.D.; Wang, T.T. Harnessing IgG Fc glycosylation for clinical benefit. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2022, 77, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T. IgG Fc Glycosylation in Human Immunity. In Fc Mediated Activity of Antibodies; Ravetch, J., Nimmerjahn, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 423, pp. 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cui, M.; Liu, Q.; Liao, Q. Glycosylation of immunoglobin G in tumors: Function, regulation and clinical implications. Cancer Lett. 2022, 549, 215902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenchhoff, M.; Chung, A.W.; Roider, J.; Dugast, A.S.; Richardson, S.; Kløverpris, H.; Leslie, A.; Ndung’u, T.; Moore, P.; Alter, G.; et al. Distinct Immunoglobulin Fc Glycosylation Patterns Are Associated with Disease Nonprogression and Broadly Neutralizing Antibody Responses in Children with HIV Infection. mSphere 2020, 5, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, E.A.; Delaforge, E.; Hartmann-Petersen, R.; Skriver, K.; Kragelund, B.B. How phosphorylation impacts intrinsically disordered proteins and their function. Essays Biochem. 2022, 66, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Hong, F.; Yang, S. Protein Phosphorylation in Cancer: Role of Nitric Oxide Signaling Pathway. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilbrough, T.; Piemontese, E.; Seitz, O. Dissecting the role of protein phosphorylation: A chemical biology toolbox. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 5691–5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tigno-Aranjuez, J.T.; Abbott, D.W. Ubiquitination and phosphorylation in the regulation of NOD2 signaling and NOD2-mediated disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 2022–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, X.; Lv, J.; Li, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.F. Sequence-based machine learning method for predicting the effects of phosphorylation on protein-protein interactions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 243, 125233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Mitsuki, Y.Y.; Shen, G.; Ray, J.C.; Cicala, C.; Arthos, J.; Dustin, M.L.; Hioe, C.E. HIV Envelope gp120 Alters T Cell Receptor Mobilization in the Immunological Synapse of Uninfected CD4 T Cells and Augments T Cell Activation. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 10513–10526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, E.; Weber, C.K.; Chen, P.; Hoffmeyer, A.; Jassoy, C.; Rapp, U.R. Plasma membrane-targeted Raf kinase activates NF-kappaB and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 2788–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Len, A.C.L.; Starling, S.; Shivkumar, M.; Jolly, C. HIV-1 Activates T Cell Signaling Independently of Antigen to Drive Viral Spread. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Ho, H.P.; Buzon, M.J.; Pereyra, F.; Walker, B.D.; Yu, X.G.; Chang, E.J.; Lichterfeld, M. A cell-intrinsic inhibitor of HIV-1 reverse transcription in CD4(+) T cells from elite controllers. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H.; Saito, H.; Noda, T.; Miyamoto, T.; Yoshinaga, T.; Terahara, K.; Ishii, H.; Tsunetsugu-Yokota, Y.; Yamaoka, S. Phosphorylation of the HIV-1 capsid by MELK triggers uncoating to promote viral cDNA synthesis. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleboina, S.; Aljouda, N.; Miller, M.; Freeman, K.W. Therapeutically targeting oncogenic CRCs facilitates induced differentiation of NB by RA and the BET bromodomain inhibitor. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2021, 23, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.; Zhu, Z.; Li, H.; Hong, Q.; Wang, C.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, W.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ran, T.; et al. Discovery of 1-(5-(1H-benzo[d]imidazole-2-yl)-2,4-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)ethan-1-one derivatives as novel and potent bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) inhibitors with anticancer efficacy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 227, 113953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, R.J.; Fozouni, P.; Thomas, S.; Sy, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, M.M.; Ott, M. The Short Isoform of BRD4 Promotes HIV-1 Latency by Engaging Repressive SWI/SNF Chromatin-Remodeling Complexes. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 1001–1012.e1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egloff, S. CDK9 keeps RNA polymerase II on track. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 5543–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamitsu, K.; Fujinaga, K.; Okamoto, T. HIV Tat/P-TEFb Interaction: A Potential Target for Novel Anti-HIV Therapies. Molecules 2018, 23, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Han, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Hu, Z. Safety and Efficacy of Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal Inhibitors for the Treatment of Hematological Malignancies and Solid Tumors: A Systematic Study of Clinical Trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 621093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.S.; Tian, R.R.; Ma, M.D.; Luo, R.H.; Yang, L.M.; Peng, G.H.; Zhang, M.; Dong, X.Q.; Zheng, Y.T. Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal Inhibitor BMS-986158 Reverses Latent HIV-1 Infection In Vitro and Ex Vivo by Increasing CDK9 Phosphorylation and Recruitment. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Yang, W.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, S.; Ni, F.; Yang, W.; Yu, X.F.; et al. The SAMHD1-MX2 axis restricts HIV-1 infection at postviral DNA synthesis. mBio 2024, 15, e0136324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, H.J.; Paine, D.N.; Fazzari, V.A.; Tipple, A.F.; Patterson, E.; de Noronha, C.M.C. Sulforaphane Reduces SAMHD1 Phosphorylation To Protect Macrophages from HIV-1 Infection. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0118722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Fahey, J.W.; Kostov, R.V.; Kensler, T.W. KEAP1 and Done? Targeting the NRF2 Pathway with Sulforaphane. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, F.; Ikeda, F. Linear ubiquitination in immune and neurodegenerative diseases, and beyond. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2022, 50, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, X. Ubiquitination in the regulation of autophagy. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2023, 55, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Xu, C.; He, W.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, W.; Tao, K.; Ding, R.; Zhang, X.; Dou, K. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP19 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression through stabilizing YAP. Cancer Lett. 2023, 577, 216439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Li, G.; Lu, Y.; Hu, M.; Ma, X. The Involvement of Ubiquitination and SUMOylation in Retroviruses Infection and Latency. Viruses 2023, 15, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alroy, I.; Tuvia, S.; Greener, T.; Gordon, D.; Barr, H.M.; Taglicht, D.; Mandil-Levin, R.; Ben-Avraham, D.; Konforty, D.; Nir, A.; et al. The trans-Golgi network-associated human ubiquitin-protein ligase POSH is essential for HIV type 1 production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, Y.; Aso, H.; Soper, A.; Yamada, E.; Moriwaki, M.; Juarez-Fernandez, G.; Koyanagi, Y.; Sato, K. A conflict of interest: The evolutionary arms race between mammalian APOBEC3 and lentiviral Vif. Retrovirology 2017, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, F.C.; Lee, J.E. Structural perspectives on HIV-1 Vif and APOBEC3 restriction factor interactions. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiec, D.; Kirchhoff, F. Antiviral factors and their counteraction by HIV-1: Many uncovered and more to be discovered. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 16, mjae005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Knecht, K.M.; Shen, Q.; Xiong, Y. Multifaceted HIV-1 Vif interactions with human E3 ubiquitin ligase and APOBEC3s. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 3407–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, K.; Takaori-Kondo, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Tomonaga, M.; Izumi, T.; Fukunaga, K.; Sasada, A.; Abudu, A.; Miyauchi, Y.; Akari, H.; et al. Ubiquitination of APOBEC3 proteins by the Vif-Cullin5-ElonginB-ElonginC complex. Virology 2006, 344, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A.; Strebel, K. HIV-1 Vpu targets cell surface markers CD4 and BST-2 through distinct mechanisms. Mol. Aspects Med. 2010, 31, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Jafari, M.; Bangar, A.; William, K.; Guatelli, J.; Lewinski, M.K. The C-Terminal End of HIV-1 Vpu Has a Clade-Specific Determinant That Antagonizes BST-2 and Facilitates Virion Release. J. Virol. 2019, 93, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.E.; Cyburt, D.; Lucas, T.M.; Gregory, D.A.; Lyddon, T.D.; Johnson, M.C. βTrCP is Required for HIV-1 Vpu Modulation of CD4, GaLV Env, and BST-2/Tetherin. Viruses 2018, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarev, A.A.; Munguia, J.; Guatelli, J.C. Serine-threonine ubiquitination mediates downregulation of BST-2/tetherin and relief of restricted virion release by HIV-1 Vpu. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodder, S.B.; Gummuluru, S. Illuminating the Role of Vpr in HIV Infection of Myeloid Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saladino, N.; Leavitt, E.; Wong, H.T.; Ji, J.H.; Ebrahimi, D.; Salamango, D.J. HIV-1 Vpr drives epigenetic remodeling to enhance virus transcription and latency reactivation. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Verma, S.; Banerjea, A.C. HIV-1 Vpr redirects host ubiquitination pathway. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 9141–9152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, F.; Boisjoli, M.; Naghavi, M.H. HIV-1 promotes ubiquitination of the amyloidogenic C-terminal fragment of APP to support viral replication. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, H.M.; Swerdlow, R.H. Amyloid precursor protein processing and bioenergetics. Brain Res. Bull. 2017, 133, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, M.J.; Prodger, J.L.; Hackman, J.; Saraf, S.; Zhu, X.; Ferreira, R.C.; Tomusange, S.; Jamiru, S.; Anok, A.; Kityamuweesi, T.; et al. Association between HIV-1 Nef-mediated MHC-I downregulation and the maintenance of the replication-competent latent viral reservoir in individuals with virally suppressed HIV-1 in Uganda: An exploratory cohort study. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, M.; Proulx, J.; Borgmann, K.; Park, I.W. Novel role of HIV-1 Nef in regulating the ubiquitination of cellular proteins. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1106591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Zhi, X.; Wang, X.; Meng, D. Protein palmitoylation and its pathophysiological relevance. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 3220–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, S.; Piao, H.L. Exploring Protein S-Palmitoylation: Mechanisms, Detection, and Strategies for Inhibitor Discovery. ACS Chem. Biol. 2024, 19, 1868–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.M.; Hang, H.C. Protein S-palmitoylation in cellular differentiation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, M.U.; van der Goot, F.G. Refining S-acylation: Structure, regulation, dynamics, and therapeutic implications. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 222, e202307103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, S.J.; Cheung See Kit, M.; Martin, B.R. Protein depalmitoylases. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 53, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.T.S.; Davis, N.G.; Conibear, E. Targeting the Ras palmitoylation/depalmitoylation cycle in cancer. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncompain, G.; Herit, F.; Tessier, S.; Lescure, A.; Del Nery, E.; Gestraud, P.; Staropoli, I.; Fukata, Y.; Fukata, M.; Brelot, A.; et al. Targeting CCR5 trafficking to inhibit HIV-1 infection. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousso, I.; Mixon, M.B.; Chen, B.K.; Kim, P.S. Palmitoylation of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein is critical for viral infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13523–13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopard, C.; Tong, P.B.V.; Tóth, P.; Schatz, M.; Yezid, H.; Debaisieux, S.; Mettling, C.; Gross, A.; Pugnière, M.; Tu, A.; et al. Cyclophilin A enables specific HIV-1 Tat palmitoylation and accumulation in uninfected cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Liu, H.; Chu, J.; Zhang, H. Functions and mechanisms of lysine crotonylation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 7163–7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerveld, M.; Besermenji, K.; Aidukas, D.; Ostrovitsa, N.; Petracca, R. Cracking Lysine Crotonylation (Kcr): Enlightening a Promising Post-Translational Modification. ChemBioChem 2025, 26, e202400639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lin, L.; Xu, F.; Feng, T.; Tao, Y.; Miao, H.; Yang, F. Protein crotonylation: Basic research and clinical diseases. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 38, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, K. Crotonylation modification and its role in diseases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1492212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.Y.; Ju, J.; Zhou, P.; Chen, H.; Wang, S.C.; Wang, K.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.Z.; Chen, Y.C.; Wang, K. The mechanisms, regulations, and functions of histone lysine crotonylation. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fan, X.; Yu, W. Regulatory Mechanism of Protein Crotonylation and Its Relationship with Cancer. Cells 2024, 13, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Ge, J. Application of crotonylation modification in pan-vascular diseases. J. Drug Target. 2024, 32, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-de la Rosa, P.A.; Aragón-Rodríguez, C.; Ceja-López, J.A.; García-Arteaga, K.F.; De-la-Peña, C. Lysine crotonylation: A challenging new player in the epigenetic regulation of plants. J. Proteomics. 2022, 255, 104488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Nguyen, D.; Archin, N.M.; Yukl, S.A.; Méndez-Lagares, G.; Tang, Y.; Elsheikh, M.M.; Thompson, G.R., 3rd; Hartigan-O’Connor, D.J.; Margolis, D.M.; et al. HIV latency is reversed by ACSS2-driven histone crotonylation. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cai, J.; Li, C.; Deng, L.; Zhu, H.; Huang, T.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, J.; Deng, K.; Hong, Z.; et al. Wogonin inhibits latent HIV-1 reactivation by downregulating histone crotonylation. Phytomedicine 2023, 116, 154855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Dewey, M.G.; Wang, L.; Falcinelli, S.D.; Wong, L.M.; Tang, Y.; Browne, E.P.; Chen, X.; Archin, N.M.; Margolis, D.M.; et al. Crotonylation sensitizes IAPi-induced disruption of latent HIV by enhancing p100 cleavage into p52. iScience 2022, 25, 103649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yao, X. Posttranslational modifications of HIV-1 integrase by various cellular proteins during viral replication. Viruses 2013, 5, 1787–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, S.G.; Lewin, S.R.; Ross, A.L.; Ananworanich, J.; Benkirane, M.; Cannon, P.; Chomont, N.; Douek, D.; Lifson, J.D.; Lo, Y.R.; et al. International AIDS Society global scientific strategy: Towards an HIV cure 2016. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magotra, A.; Kumar, M.; Kushwaha, M.; Awasthi, P.; Raina, C.; Gupta, A.P.; Shah, B.A.; Gandhi, S.G.; Chaubey, A. Epigenetic modifier induced enhancement of fumiquinazoline C production in Aspergillus fumigatus (GA-L7): An endophytic fungus from Grewia asiatica L. AMB Express 2017, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, H.T.; Ding, J.W.; Yu, S.Y.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Q.L.; Liang, F.J. Progress and challenges in the use of latent HIV-1 reactivating agents. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.L.; Huang, Y.F.; Li, Y.B.; Liang, T.Z.; Zheng, T.Y.; Chen, P.; Wu, Z.Y.; Lai, F.Y.; Liu, S.W.; Xi, B.M.; et al. A New Small-Molecule Compound, Q308, Silences Latent HIV-1 Provirus by Suppressing Tat- and FACT-Mediated Transcription. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0047021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediouni, S.; Lyu, S.; Schader, S.M.; Valente, S.T. Forging a Functional Cure for HIV: Transcription Regulators and Inhibitors. Viruses 2022, 14, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, A.; Mahajan, T.; Coronado, R.A.; Ma, K.; Demma, D.R.; Dar, R.D. Synergistic Chromatin-Modifying Treatments Reactivate Latent HIV and Decrease Migration of Multiple Host-Cell Types. Viruses 2021, 13, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellmer, A.; Stangl, H.; Beyer, M.; Grünstein, E.; Leonhardt, M.; Pongratz, H.; Eichhorn, E.; Elz, S.; Striegl, B.; Jenei-Lanzl, Z.; et al. Marbostat-100 Defines a New Class of Potent and Selective Antiinflammatory and Antirheumatic Histone Deacetylase 6 Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 3454–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhwitine, J.P.; Kumalo, H.M.; Ndlovu, S.I.; Mkhwanazi, N.P. Epigenetic Induction of Secondary Metabolites Production in Endophytic Fungi Penicillium chrysogenum and GC-MS Analysis of Crude Metabolites with Anti-HIV-1 Activity. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, G.; Mota, T.M.; Li, S.; Tumpach, C.; Lee, M.Y.; Jacobson, J.; Harty, L.; Anderson, J.L.; Lewin, S.R.; Purcell, D.F.J. HIV latency reversing agents act through Tat post translational modifications. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matalon, S.; Rasmussen, T.A.; Dinarello, C.A. Histone deacetylase inhibitors for purging HIV-1 from the latent reservoir. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T.A.; Schmeltz Søgaard, O.; Brinkmann, C.; Wightman, F.; Lewin, S.R.; Melchjorsen, J.; Dinarello, C.; Østergaard, L.; Tolstrup, M. Comparison of HDAC inhibitors in clinical development: Effect on HIV production in latently infected cells and T-cell activation. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.G.; Chiang, V.; Fyne, E.; Balakrishnan, M.; Barnes, T.; Graupe, M.; Hesselgesser, J.; Irrinki, A.; Murry, J.P.; Stepan, G.; et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin induces HIV expression in CD4 T cells from patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy at concentrations achieved by clinical dosing. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, S.G. HIV: Shock and kill. Nature 2012, 487, 439–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boumber, Y.; Younes, A.; Garcia-Manero, G. Mocetinostat (MGCD0103): A review of an isotype-specific histone deacetylase inhibitor. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2011, 20, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagans, S.; Pedal, A.; North, B.J.; Kaehlcke, K.; Marshall, B.L.; Dorr, A.; Hetzer-Egger, C.; Henklein, P.; Frye, R.; McBurney, M.W.; et al. SIRT1 regulates HIV transcription via Tat deacetylation. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, R.M.; Brumme, Z.L.; Sadowski, I. CDK8 inhibitors antagonize HIV-1 reactivation and promote provirus latency in T cells. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0092323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, S.; Deng, W.; Peng, D.; Cui, Q.; Xue, Y. PTMD: A Database of Human Disease-associated Post-translational Modifications. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2018, 16, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abner, E.; Jordan, A. HIV “shock and kill” therapy: In need of revision. Antivir. Res. 2019, 166, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, H.; Guo, N.; Su, B.; Lambotte, O.; Zhang, T. Targeting the HIV reservoir: Chimeric antigen receptor therapy for HIV cure. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 2658–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug/Compound Name | Category | Mechanism of Action | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| vorinostat | Hydroxamic acids | Inhibits histone deacetylases, increasing chromatin acetylation. Acetylated histones exhibit reduced positive charge, diminishing their affinity for DNA. This unlocks closed HIV promoter regions, thereby activating viral transcription. | [121] |

| trichostatin A | hydroxamic acids | [124] | |

| Marbostat-100 | benzamides | [125] | |

| sodium butyrate | Short chain aliphatic acids | [126] | |

| valproic acid | Short chain aliphatic acids | [126] | |

| panobinostat | Hydroxamic acids | [127] | |

| Butyric acid | Short chain aliphatic acids | [121] | |

| givinostat | Hydroxamic acids | [128] | |

| panobinostat | Hydroxamic acids | [129] | |

| Romidepsin | Cyclic tetrapeptides | [130] | |

| Entinostat | benzamides | [131] | |

| mocetinostat | benzamides | [132] | |

| AZD5582 | dimeric peptidomimetic small molecule | AZD5582 induces the auto-ubiquitination of cIAP1 and its degradation via the proteasome, thereby relieving its inhibition on NIK and activating the non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. Ultimately enhancing the reactivation of latent HIV. Additionally, this process is enhanced by palmitoylation. | [117] |

| HR73 | Small-molecule heteroaromatic organic compound | Blocking Tat deacetylation prevents it from binding to trans-acting responsive element, CyclinT1 and CDK9 to initiate transcription and thus inhibits latent HIV reactivation | [133] |

| wogonin | Flavone | Inhibits the reactivation of latent HIV-1 by inhibiting the expression of p300, a histone acetyltransferase, and decreasing the crotonylation of histone H3/H4 in the HIV-1 promoter region. | [116] |

| Senexin A | Small-molecule synthetic heterocyclic compound | By inhibiting the phosphorylation of the transcriptional activator mediated by CDK8/19, the assembly of RNA polymerase II to the HIV promoter region is prevented, thereby inhibiting the reactivation of latent HIV. | [134] |

| BRD6989 | Small-molecule synthetic heteroaromatic compound | [134] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Yang, S.; Ao, Y.; Yu, W. Post-Translational Modifications in HIV Infection: Novel Antiretroviral Strategies. Cells 2026, 15, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030243

Sun Y, Yang S, Ao Y, Yu W. Post-Translational Modifications in HIV Infection: Novel Antiretroviral Strategies. Cells. 2026; 15(3):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030243

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yidong, Siyi Yang, Youxi Ao, and Wei Yu. 2026. "Post-Translational Modifications in HIV Infection: Novel Antiretroviral Strategies" Cells 15, no. 3: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030243

APA StyleSun, Y., Yang, S., Ao, Y., & Yu, W. (2026). Post-Translational Modifications in HIV Infection: Novel Antiretroviral Strategies. Cells, 15(3), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030243