Lactic Acid Bacteria Postbiotics as Adjunctives to Glioblastoma Therapy to Fight Treatment Escape and Protect Non-Neoplastic Cells from Side Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culturing Bacteria and Preparing Cell-Free Supernatant

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Compounds: Natural and Synthetic

2.4. IDH Status Verification

2.5. Cell Viability Assay

2.6. Cell Death Assay—Annexin V/PI Staining

2.7. Proliferation Analysis

2.8. SA-β-Gal Detection-Based Cellular Senescence Assay

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

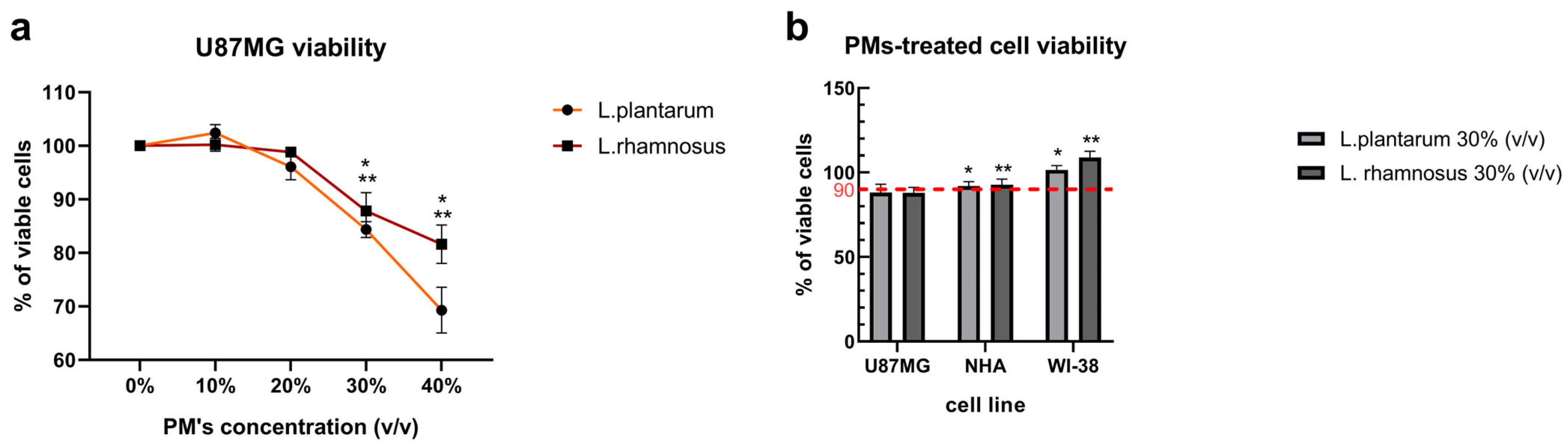

3.1. Initial Screening of L. plantarum and L. rhamnosus-Derived PM Activity Shows Cytotoxicity Towards GB Cells and Cytoprotective Potential Against Anti-Cancer Agent—ARA12

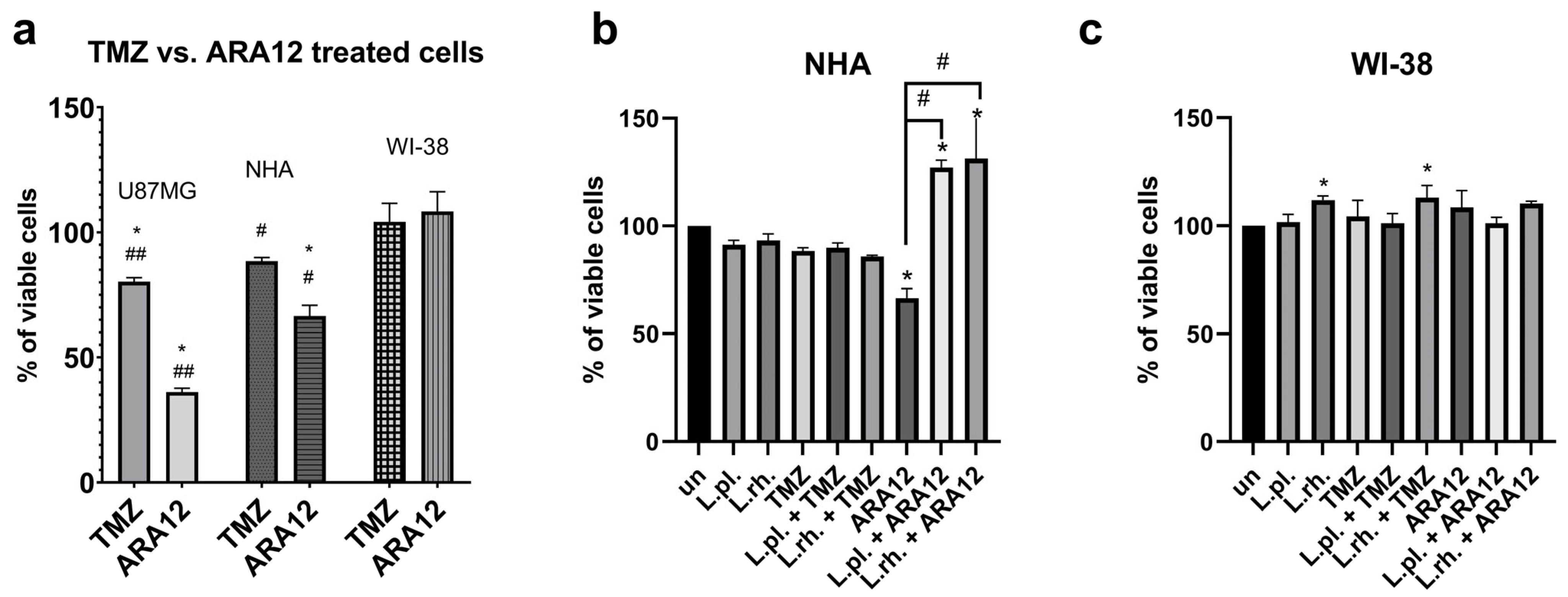

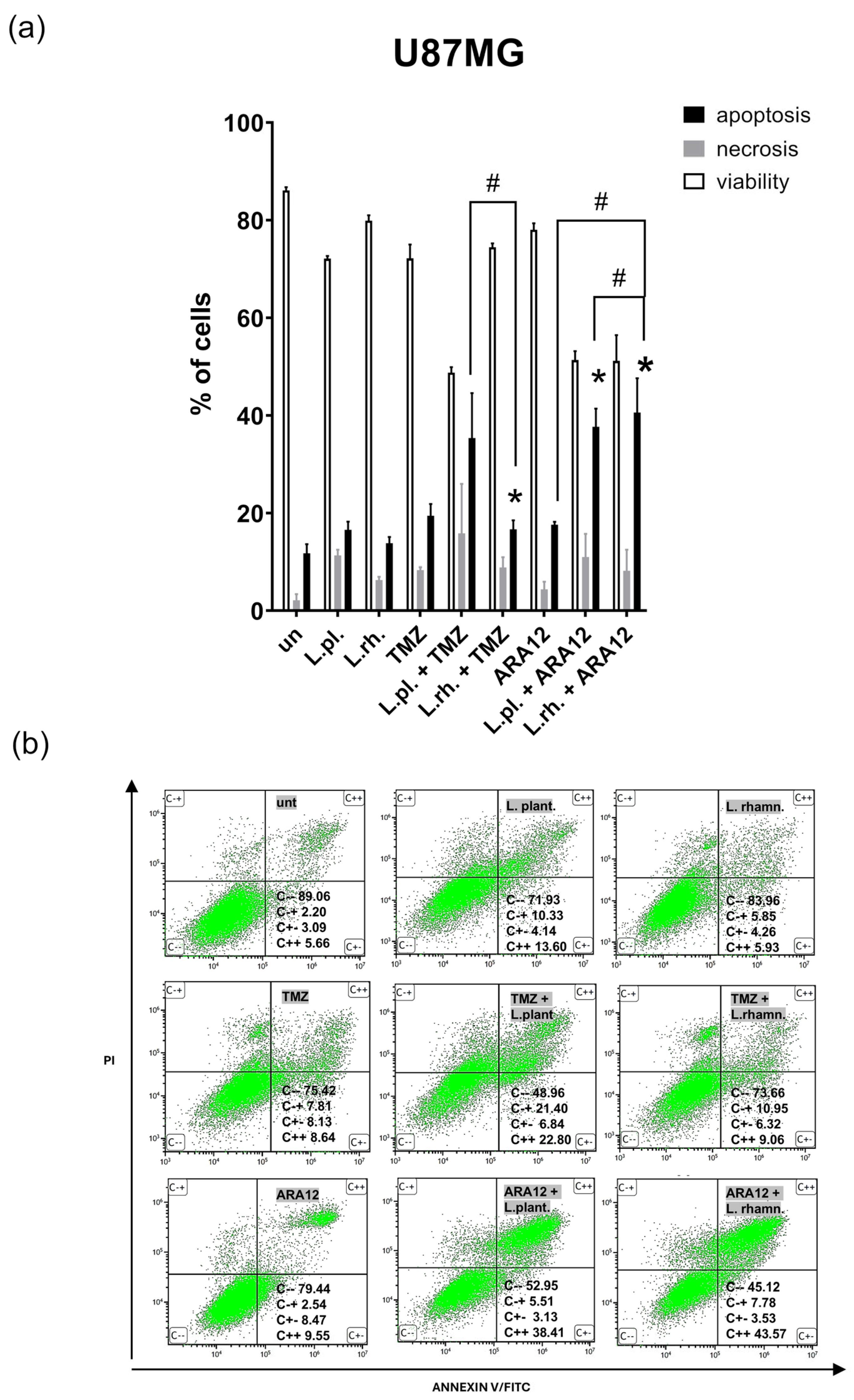

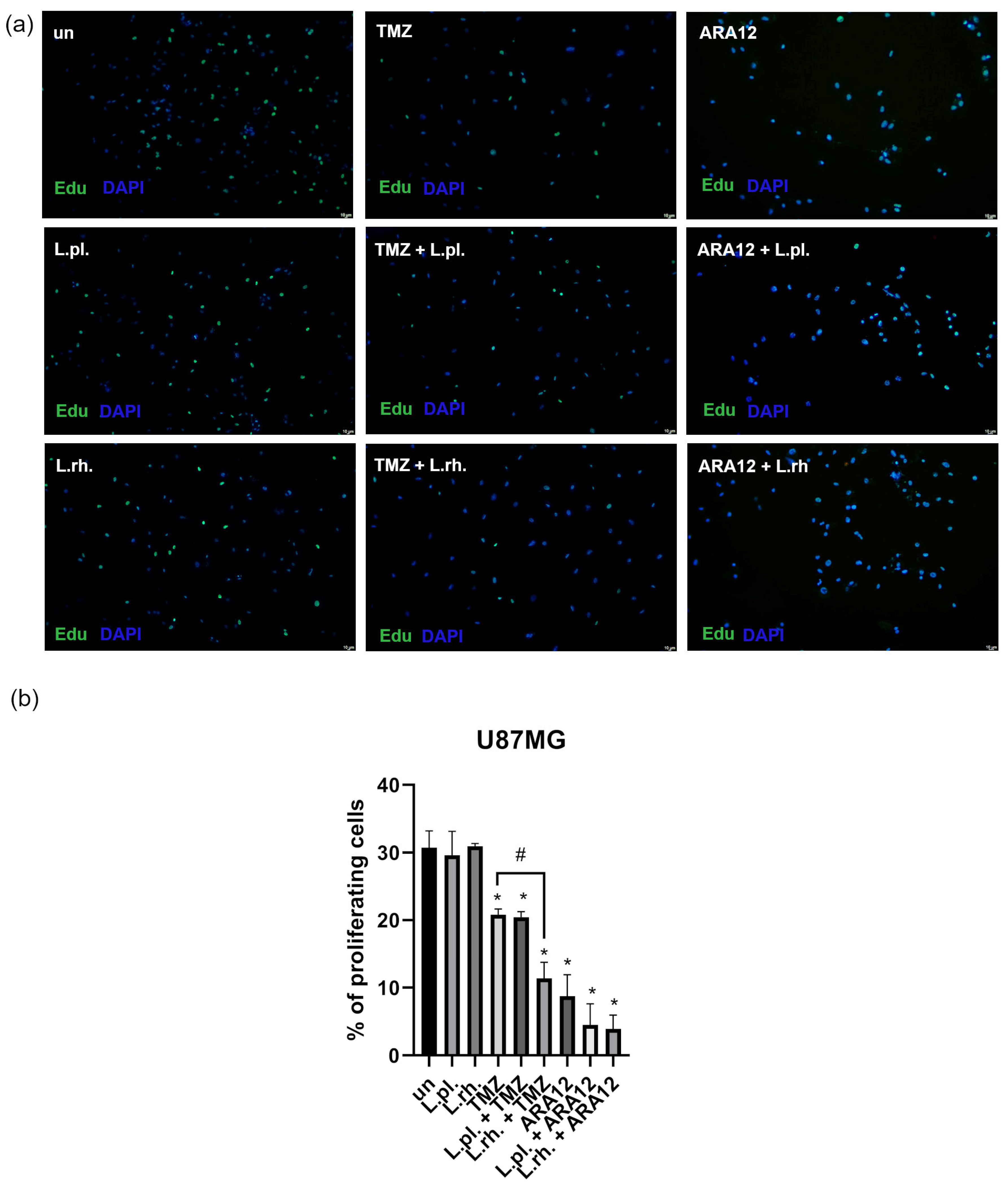

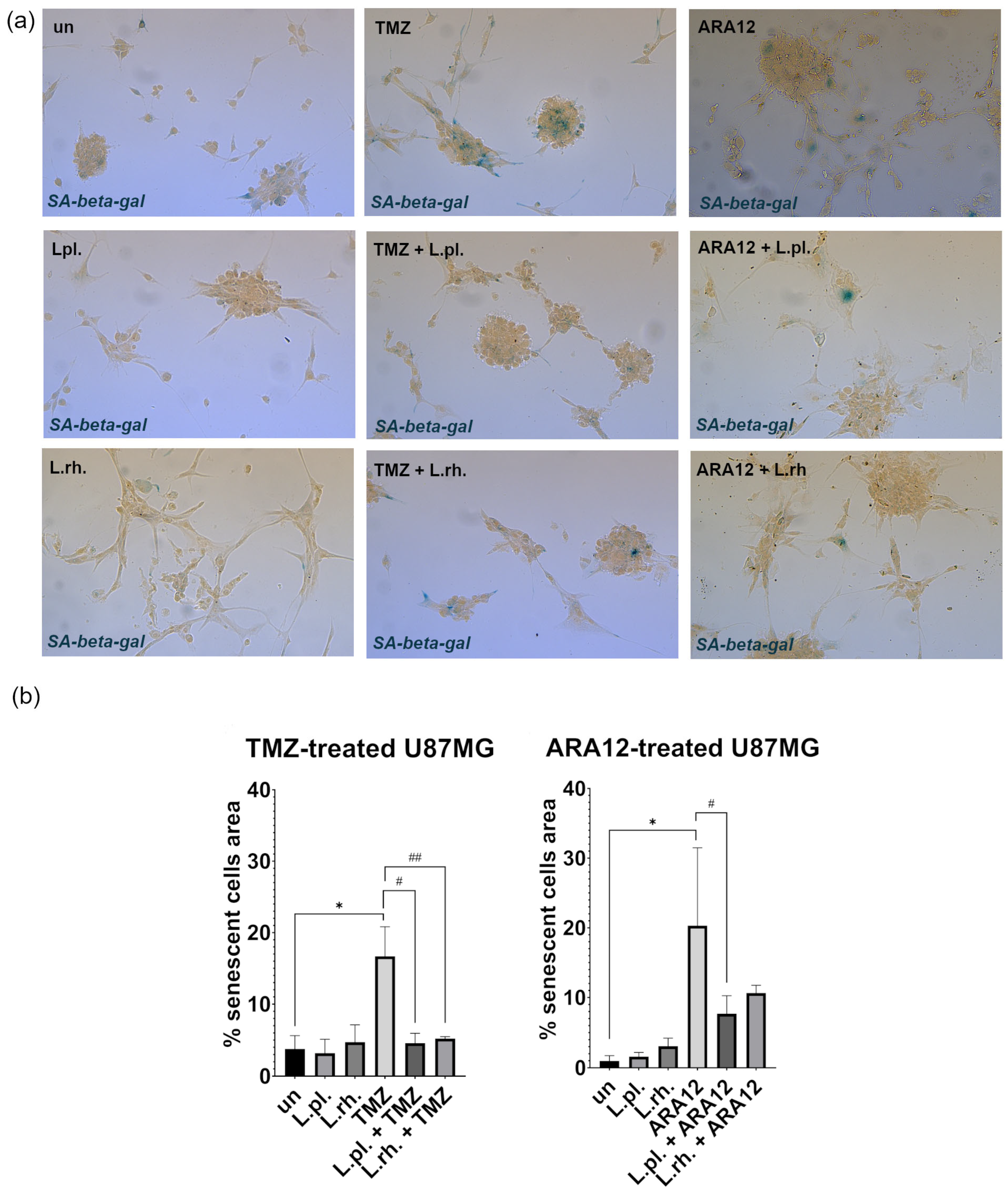

3.2. The Enhanced Proapoptotic, Antiproliferative, and Anti-Senescent Effect of L. plantarum- and L. rhamnosus-Derived PM on U87MG Glioblastoma Cell Line

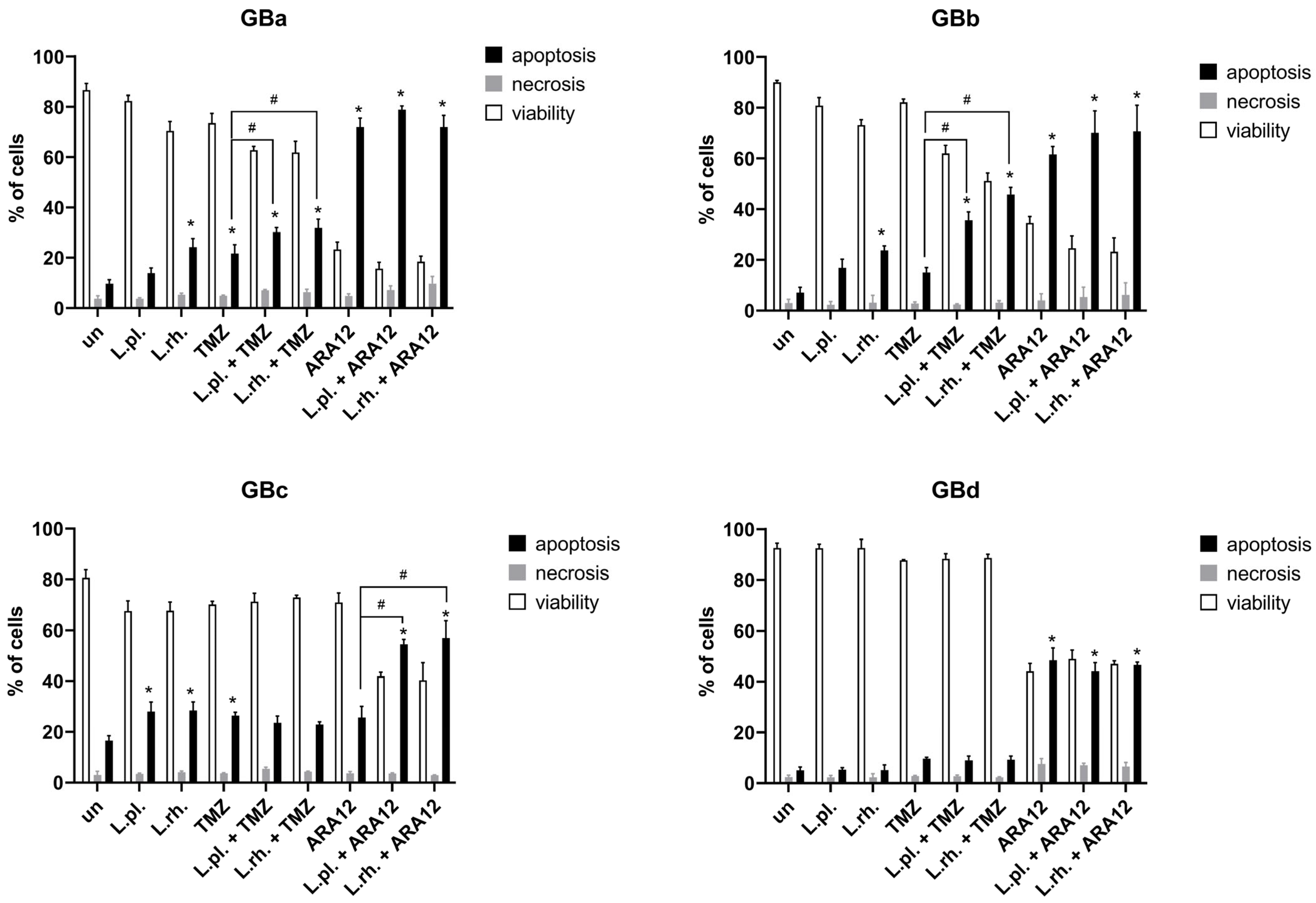

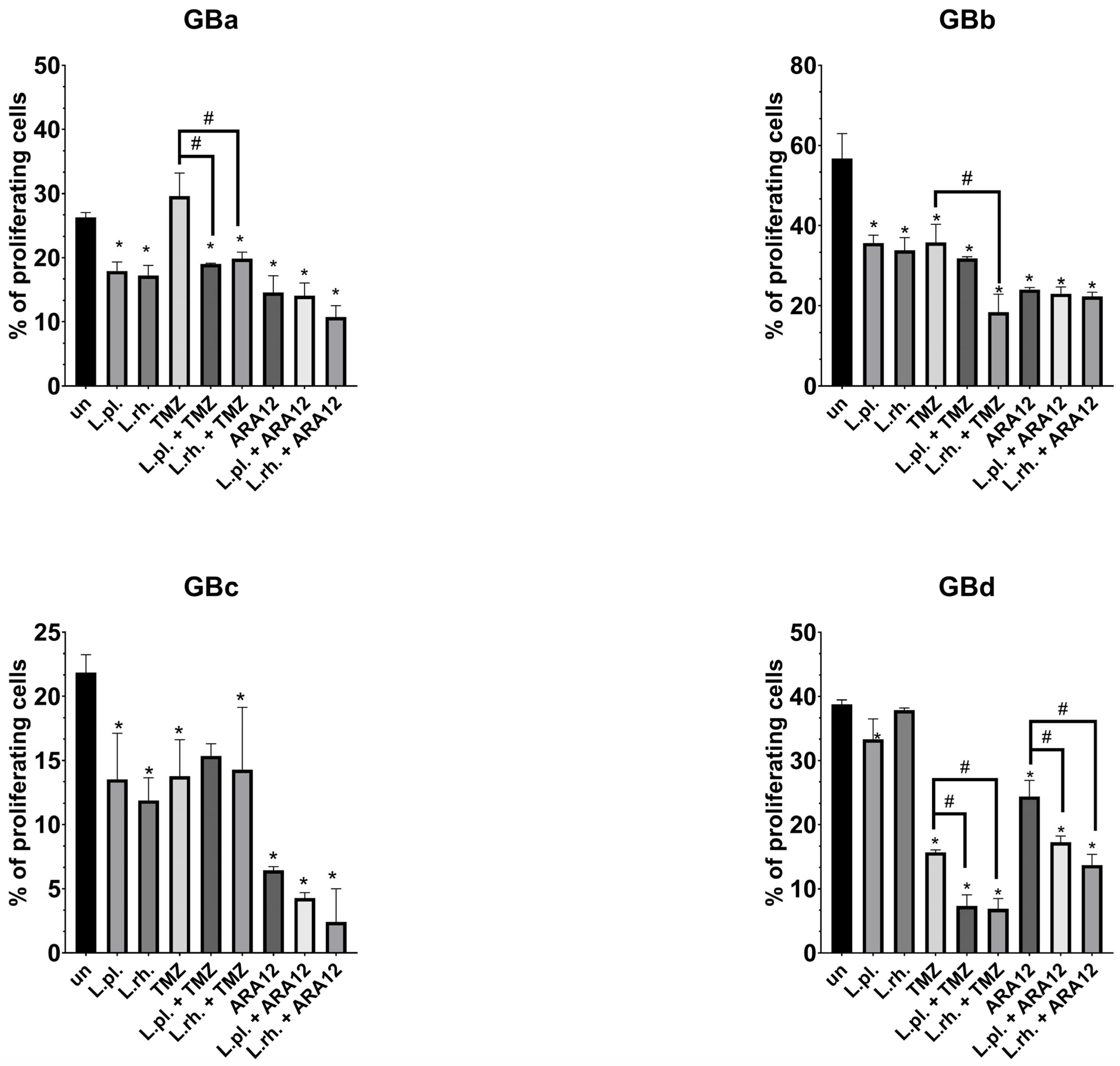

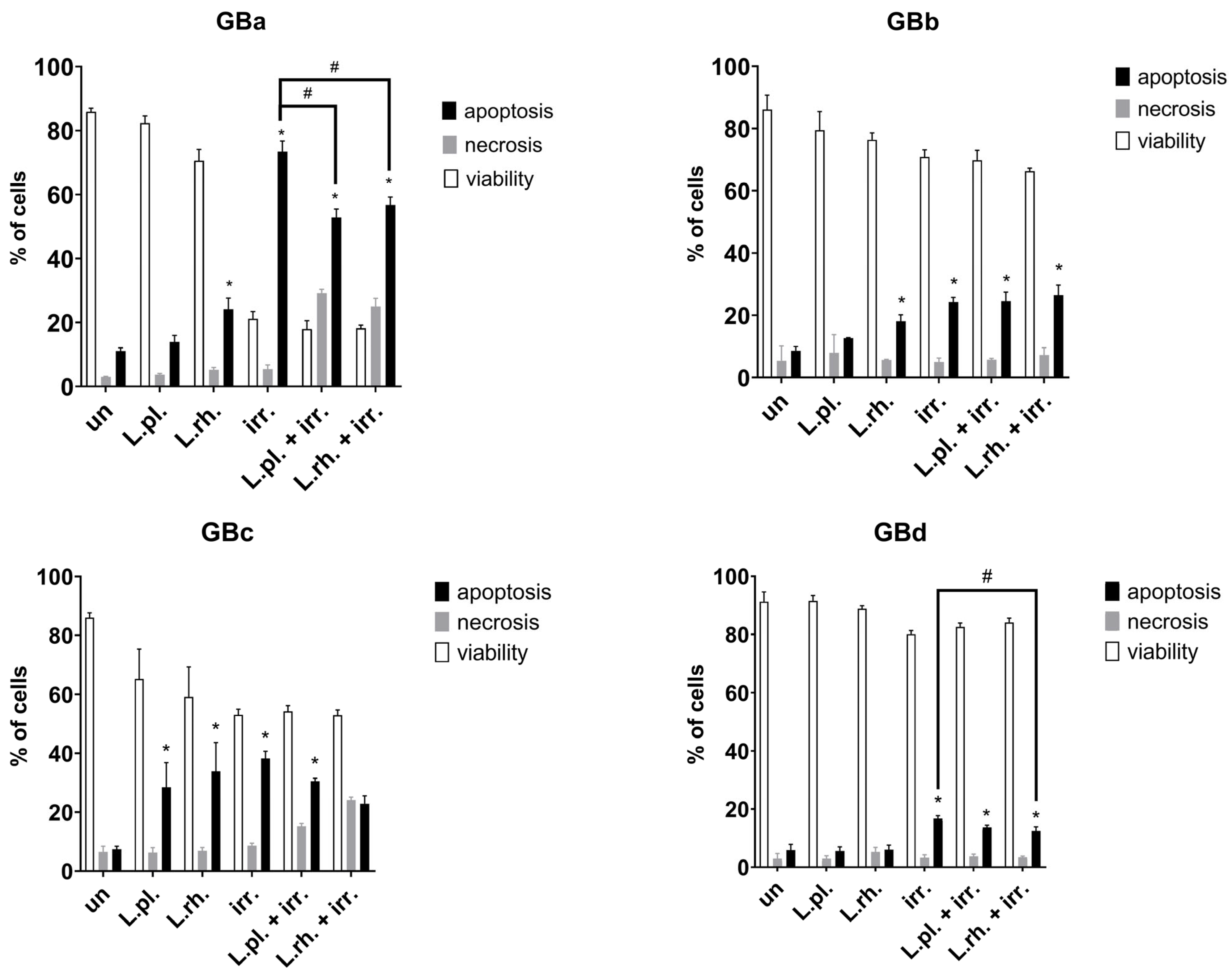

3.3. Patient-Derived GB Cell Lines Present Heterogenous Responsiveness to Proapoptotic and Antiproliferative Effect of L. plantarum- and L. rhamnosus-Derived PM in Combination with Anti-Neoplastic Drugs

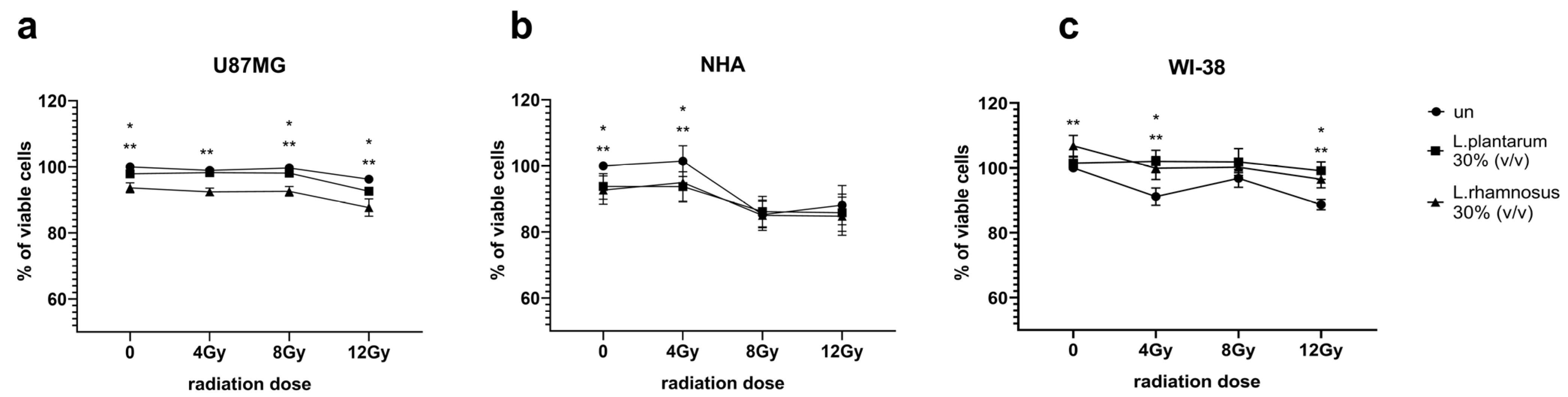

3.4. Initial Screening of L. plantarum- and L. rhamnosus-Derived PM Activity Towards GB and Normal Cells Undergoing Irradiation Process Demonstrates More Evident Influence of PM in Maximal Tested Radiation Dose

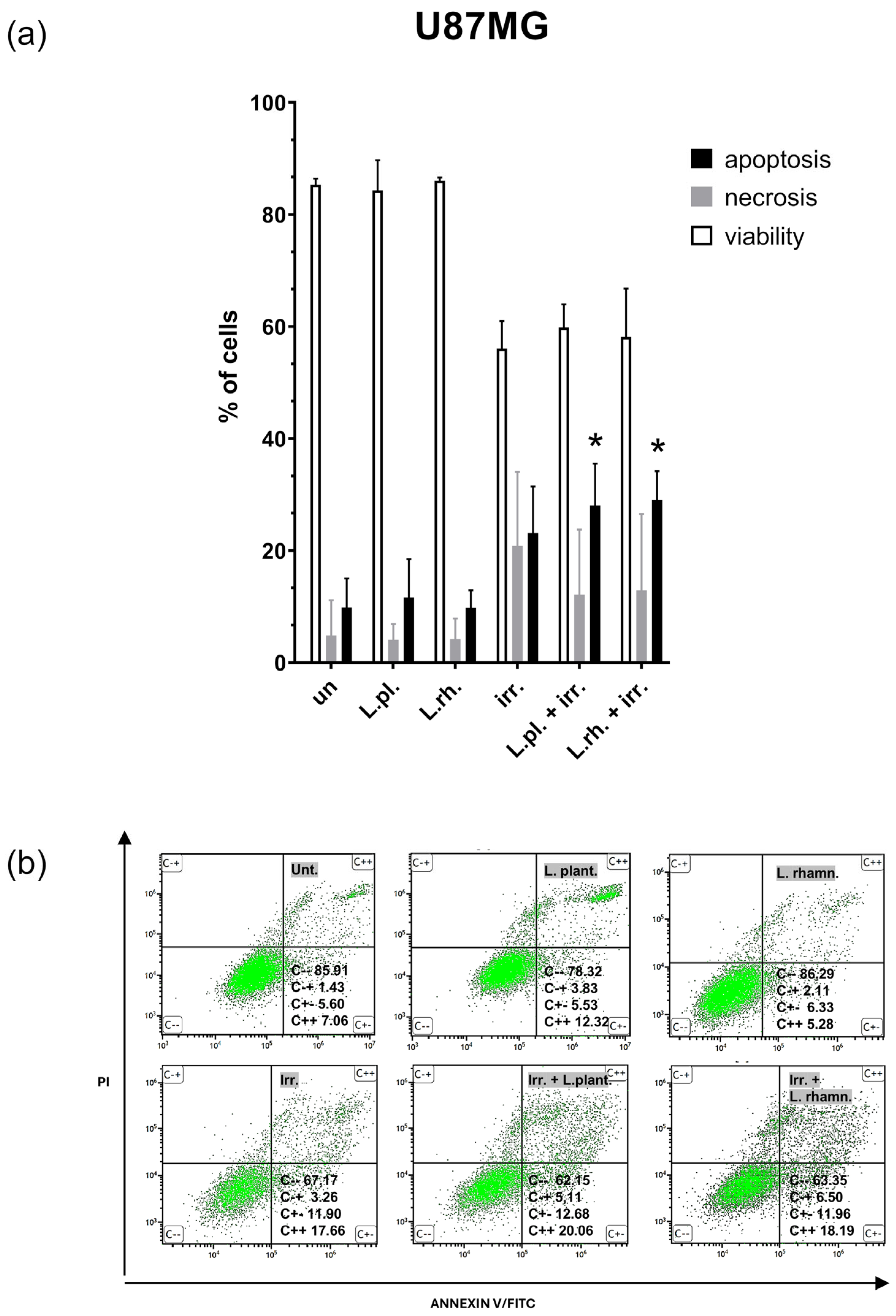

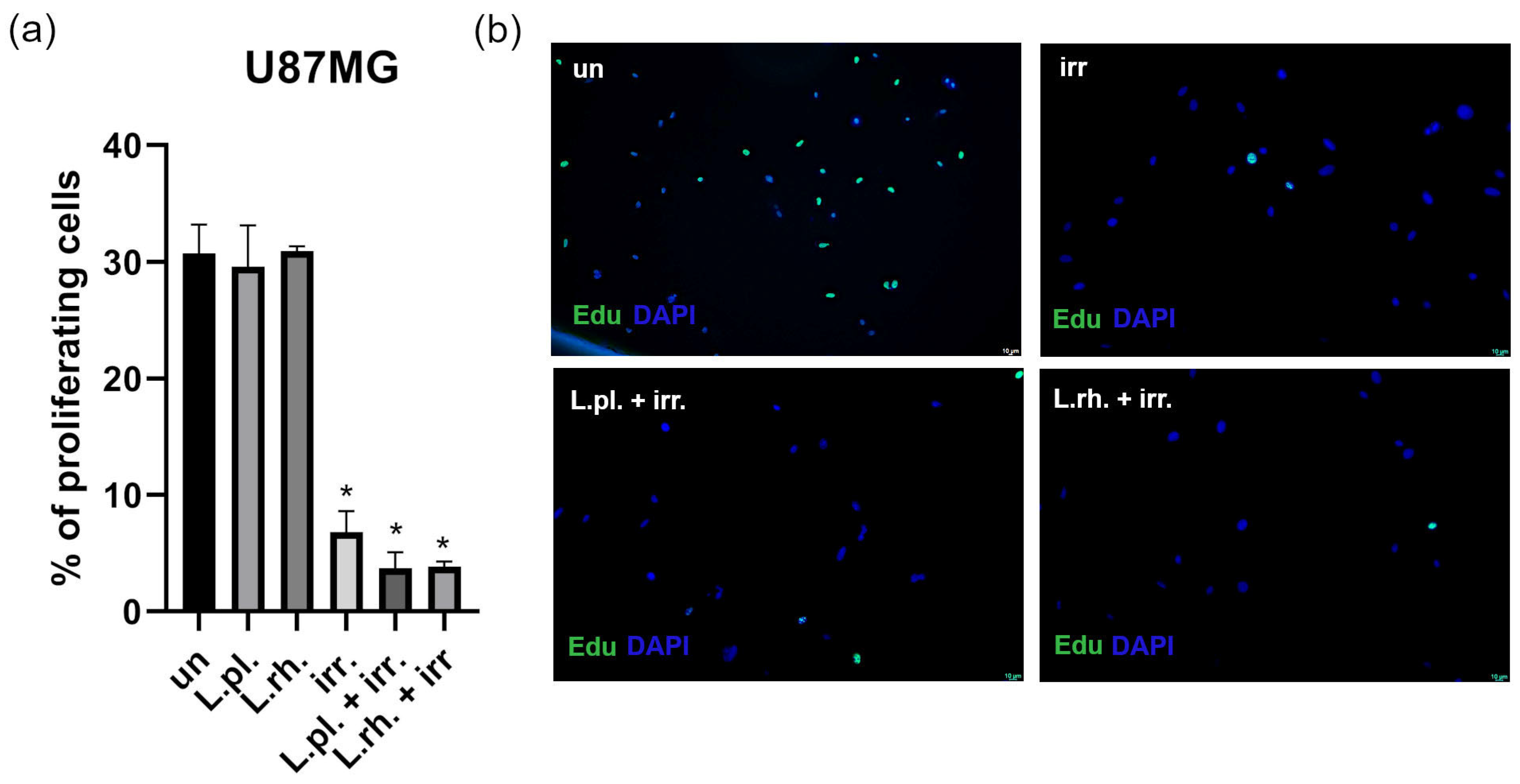

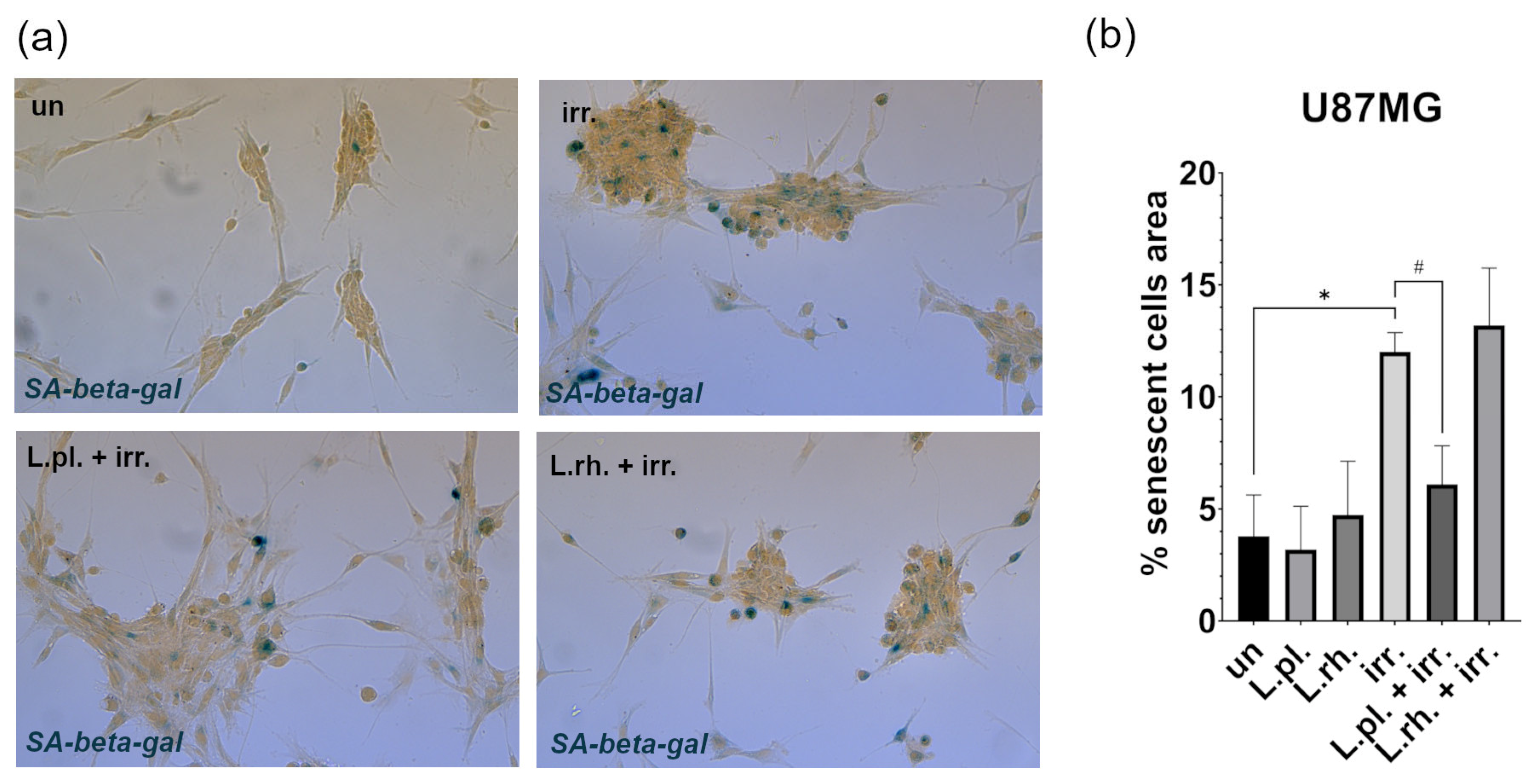

3.5. Examined Postbiotics Modestly Enhance Apoptosis in Irradiated U87MG Cells and L. plantarum PMs Mitigate Pro-Senescent Irradiation Effect

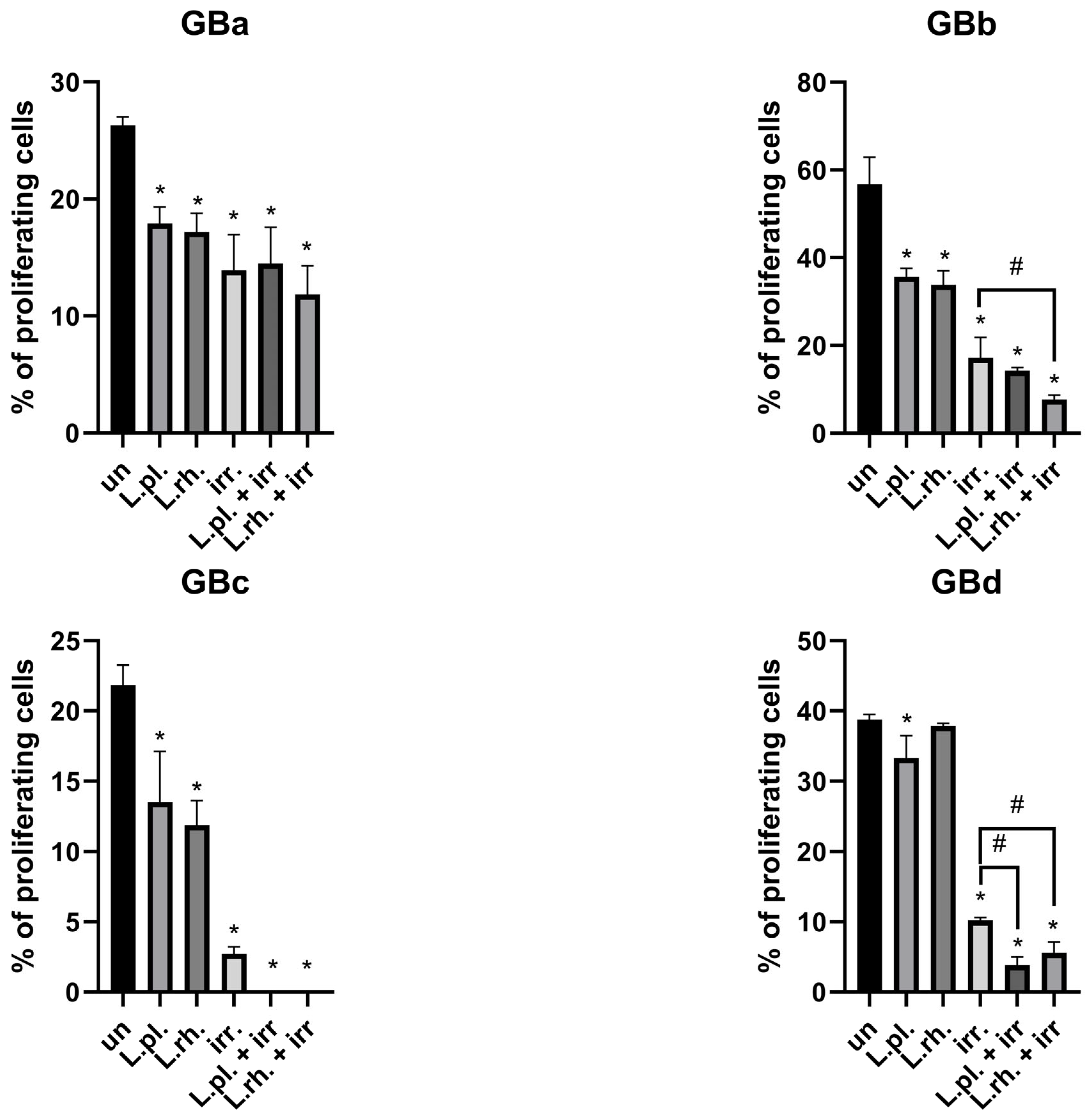

3.6. The Effect of Pretreatment with L. plantarum- and L. rhamnosus-Derived PM in Combination with Irradiation on Cell Death Processes and Proliferation Rate Varies Between Examined GB Patient-Derived Cell Lines

3.7. Short Summary of Postbiotic Effect on Examined Processes in Patient-Derived GB Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNS | central nervous system |

| EdU+ | EdU-positive cells |

| FC | flow cytometry |

| GB | glioblastoma |

| IDH | isocitrate dehydrogenase |

| Irr. | irradiated |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| L. plantarum; L.pl | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum |

| L. rhamnosus; L.rh | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus |

| NHA | normal human astrocytes |

| PI | propidium iodide |

| PM | postbiotic mixture |

| SASP | senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SCFA | short chain fatty acid |

| TMZ | temozolomide |

| un | untreated |

References

- Sipos, D.; Raposa, B.L.; Freihat, O.; Simon, M.; Mekis, N.; Cornacchione, P.; Kovács, Á. Glioblastoma: Clinical Presentation, Multidisciplinary Management, and Long-Term Outcomes. Cancers 2025, 17, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A Summary. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Janzer, R.C.; Ludwin, S.K.; Allgeier, A.; Fisher, B.; Belanger, K.; et al. Effects of Radiotherapy with Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide versus Radiotherapy Alone on Survival in Glioblastoma in a Randomised Phase III Study: 5-Year Analysis of the EORTC-NCIC Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabah, N.; Ait Mohand, F.-E.; Kravchenko-Balasha, N. Understanding Glioblastoma Signaling, Heterogeneity, Invasiveness, and Drug Delivery Barriers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Rick, J.W.; Joshi, R.S.; Beniwal, A.; Spatz, J.; Gill, S.; Chang, A.C.-C.; Choudhary, N.; Nguyen, A.T.; Sudhir, S.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing and Spatial Transcriptomics Reveal Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Glioblastoma with Protumoral Effects. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e147087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.Y.; Oliva, C.R.; Noman, A.S.M.; Allen, B.G.; Goswami, P.C.; Zakharia, Y.; Monga, V.; Spitz, D.R.; Buatti, J.M.; Griguer, C.E. Radioresistance in Glioblastoma and the Development of Radiosensitizers. Cancers 2020, 12, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Ge, Z.; Tian, F.; Tai, X.; Chen, D.; Sun, S.; Shi, Z.; Yin, J.; Wei, G.; Li, D.; et al. Sulforaphane Potentiates the Efficacy of Chemoradiotherapy in Glioblastoma by Selectively Targeting Thioredoxin Reductase 1. Cancer Lett. 2024, 611, 217429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Meng, C.; Han, X.; Guo, J.; Li, H.; Yu, Z. Low-Dose Cisplatin Causes Growth Inhibition and Loss of Autophagy of Rat Astrocytes In Vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 682, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Kurose, A.; Ogawa, A.; Ogasawara, K.; Traganos, F.; Darzynkiewicz, Z.; Sawai, T. Diversity of DNA Damage Response of Astrocytes and Glioblastoma Cell Lines with Various P53 Status to Treatment with Etoposide and Temozolomide. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2009, 8, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongnok, B.; Khuanjing, T.; Chunchai, T.; Pantiya, P.; Kerdphoo, S.; Arunsak, B.; Nawara, W.; Jaiwongkam, T.; Apaijai, N.; Chattipakorn, N.; et al. Donepezil Protects Against Doxorubicin-Induced Chemobrain in Rats via Attenuation of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Without Interfering with Doxorubicin Efficacy. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 2107–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenbach, C.; Rinke, J.; Vilar, J.B.; Sallbach, J.; Tatsch, L.; Schmidt, A.; Schöneis, A.; Rasenberger, B.; Kaina, B.; Tomicic, M.T.; et al. Therapy-Induced Senescence of Glioblastoma Cells Is Determined by the p21CIP1-CDK1/2 Axis and Does Not Require Activation of DREAM. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBenedict, B.; Hauwanga, W.N.; Pogodina, A.; Singh, G.; Thomas, A.; Ibrahim, A.M.A.; Johnny, C.; Lima Pessôa, B. Approaches in Adult Glioblastoma Treatment: A Systematic Review of Emerging Therapies. Cureus 2024, 16, e67856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witusik-Perkowska, M.; Głowacka, P.; Pieczonka, A.M.; Świderska, E.; Pudlarz, A.; Rachwalski, M.; Szymańska, J.; Zakrzewska, M.; Jaskólski, D.J.; Szemraj, J. Autophagy Inhibition with Chloroquine Increased Pro-Apoptotic Potential of New Aziridine-Hydrazide Hydrazone Derivatives against Glioblastoma Cells. Cells 2023, 12, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiak, J.; Głowacka, P.; Pudlarz, A.; Pieczonka, A.M.; Dzitko, K.; Szemraj, J.; Witusik-Perkowska, M. Lactic Acid Bacteria-Derived Postbiotics as Adjunctive Agents in Breast Cancer Treatment to Boost the Antineoplastic Effect of a Conventional Therapeutic Comprising Tamoxifen and a New Drug Candidate: An Aziridine–Hydrazide Hydrazone Derivative. Molecules 2024, 29, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Xue, J.; Shao, R.; Mo, C.; Wang, F.; Chen, G. Postbiotics as Potential New Therapeutic Agents for Sepsis. Burn. Trauma 2023, 11, tkad022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinderola, G.; Sanders, M.E.; Salminen, S. The Concept of Postbiotics. Foods 2022, 11, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, L.-O.; Foo, H.L.; Loh, T.C.; Mohammed Alitheen, N.B.; Yeap, S.K.; Abdul Mutalib, N.E.; Abdul Rahim, R.; Yusoff, K. Postbiotic Metabolites Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum Strains Exert Selective Cytotoxicity Effects on Cancer Cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głowacka, P.; Oszajca, K.; Pudlarz, A.; Szemraj, J.; Witusik-Perkowska, M. Postbiotics as Molecules Targeting Cellular Events of Aging Brain—The Role in Pathogenesis, Prophylaxis and Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balendra, V.; Rosenfeld, R.; Amoroso, C.; Castagnone, C.; Rossino, M.G.; Garrone, O.; Ghidini, M. Postbiotics as Adjuvant Therapy in Cancer Care. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cao, W.; Li, L.; Liu, K.; Zhu, H.; Balcha, F.; Fang, Y. Extracellular Vesicles from Lacticaseibacillus paracasei PC-H1 Inhibit HIF-1α-Mediated Glycolysis of Colon Cancer. Future Microbiol. 2024, 19, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S.M.; Carter, L.C.; Mak, J.; Tsau, J.; Yamamoto, S.; German, J.B. Butyric Acid and Tributyrin Induce Apoptosis in Human Hepatic Tumour Cells. J. Dairy Res. 1999, 66, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, V.; Lo Cascio, A.; Melacarne, A.; Tanasković, N.; Mozzarelli, A.M.; Tiraboschi, L.; Lizier, M.; Salvi, M.; Braga, D.; Algieri, F.; et al. Sensitizing Cancer Cells to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors by Microbiota-Mediated Upregulation of HLA Class I. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1717–1730.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yang, F.; Zhang, X.; Fang, H.; Qiu, T.; Li, Y.; Peng, A. Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiota in Glioblastoma Patients and Potential Biomarkers for Risk Assessment. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 195, 106888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, S.; Zang, D.; Sun, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J. Butyrate as a Promising Therapeutic Target in Cancer: From Pathogenesis to Clinic (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2024, 64, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thananimit, S.; Pahumunto, N.; Teanpaisan, R. Characterization of Short Chain Fatty Acids Produced by Selected Potential Probiotic Lactobacillus Strains. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Folwarski, M.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Ruszkowski, J.; Makarewicz, W. The Use of Lactobacillus plantarum 299v (DSM 9843) in Cancer Patients Receiving Home Enteral Nutrition—Study Protocol for a Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witusik-Perkowska, M.; Zakrzewska, M.; Szybka, M.; Papierz, W.; Jaskolski, D.J.; Liberski, P.P.; Sikorska, B. Astrocytoma-Associated Antigens—IL13Rα2, Fra-1, and EphA2 as Potential Markers to Monitor the Status of Tumour-Derived Cell Cultures In Vitro. Cancer Cell Int. 2014, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witusik-Perkowska, M.; Zakrzewska, M.; Sikorska, B.; Papierz, W.; Jaskolski, D.J.; Szemraj, J.; Liberski, P.P. Glioblastoma-Derived Cells In Vitro Unveil the Spectrum of Drug Resistance Capability—Comparative Study of Tumour Chemosensitivity in Different Culture Systems. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37, BSR20170058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.; Reimand, J.; Lan, X.; Head, R.; Zhu, X.; Kushida, M.; Bayani, J.; Pressey, J.C.; Lionel, A.C.; Clarke, I.D.; et al. Single Cell-Derived Clonal Analysis of Human Glioblastoma Links Functional and Genomic Heterogeneity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Kwak, J.; Kim, K.-W.; Jung, S.; Nam, C.H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.M.; Choi, C.; Ahn, Y.; Park, J.-H.; et al. IDH-Mutant Gliomas Arise from Glial Progenitor Cells Harboring the Initial Driver Mutation. Science 2026, 391, eadt0559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltzig, L.; Schwarzenbach, C.; Leukel, P.; Frauenknecht, K.B.M.; Sommer, C.; Tancredi, A.; Hegi, M.E.; Christmann, M.; Kaina, B. Senescence Is the Main Trait Induced by Temozolomide in Glioblastoma Cells. Cancers 2022, 14, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, R.; Saliou, A.; Bielle, F.; Bertrand, M.; Antoniewski, C.; Carpentier, C.; Alentorn, A.; Capelle, L.; Sanson, M.; Huillard, E.; et al. Cellular Senescence in Malignant Cells Promotes Tumor Progression in Mouse and Patient Glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Sananikone, E.; Kanji, S.; Tomimatsu, N.; Di Cristofaro, L.F.M.; Kollipara, R.K.; Saha, D.; Floyd, J.R.; Sung, P.; Hromas, R.; Burns, T.C.; et al. Elimination of Radiation-Induced Senescence in the Brain Tumor Microenvironment Attenuates Glioblastoma Recurrence. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 5935–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zeng, L.; Cai, L.; Zheng, W.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Jin, X.; Bai, Y.; Lai, M.; Li, H.; et al. Cellular Senescence-Associated Gene IFI16 Promotes HMOX1-Dependent Evasion of Ferroptosis and Radioresistance in Glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Chiano, M.; Rocchetti, M.T.; Spano, G.; Russo, P.; Allegretta, C.; Milior, G.; Gadaleta, R.M.; Sallustio, F.; Pontrelli, P.; Gesualdo, L.; et al. Lactobacilli Cell-Free Supernatants Modulate Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Human Microglia via NRF2-SOD1 Signaling. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 44, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; D’Amico, D.; Andreux, P.A.; Fouassier, A.M.; Blanco-Bose, W.; Evans, M.; Aebischer, P.; Auwerx, J.; Rinsch, C. Urolithin A Improves Muscle Strength, Exercise Performance, and Biomarkers of Mitochondrial Health in a Randomized Trial in Middle-Aged Adults. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, B.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, G.; Gao, Y.; Li, F.; Li, S. Anticancer Effects of Weizmannia coagulans MZY531 Postbiotics in CT26 Colorectal Tumor-Bearing Mice by Regulating Apoptosis and Autophagy. Life 2024, 14, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panebianco, C.; Villani, A.; Pisati, F.; Orsenigo, F.; Ulaszewska, M.; Latiano, T.P.; Potenza, A.; Andolfo, A.; Terracciano, F.; Tripodo, C.; et al. Butyrate, a Postbiotic of Intestinal Bacteria, Affects Pancreatic Cancer and Gemcitabine Response in In Vitro and In Vivo Models. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltzig, L.; Christmann, M.; Kaina, B. Abrogation of Cellular Senescence Induced by Temozolomide in Glioblastoma Cells: Search for Senolytics. Cells 2022, 11, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkotub, B.; Bauer, L.; Bashiri Dezfouli, A.; Hachani, K.; Ntziachristos, V.; Multhoff, G.; Kafshgari, M.H. Radiosensitizing Capacity of Fenofibrate in Glioblastoma Cells Depends on Lipid Metabolism. Redox Biol. 2025, 79, 103452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; Qaisar, S.A.; Janeh, T.; Karimpour, H.; Darbandi, M.; Moludi, J. Clinical Trial of the Effects of Postbiotic Supplementation on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with CVA. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.K.; Israelsen, M.; Nishijima, S.; Stinson, S.E.; Andersen, P.; Johansen, S.; Hansen, C.D.; Brol, M.J.; Klein, S.; Schierwagen, R.; et al. The Postbiotic ReFerm® versus Standard Nutritional Support in Advanced Alcohol-Related Liver Disease (GALA-POSTBIO): A Randomized Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanihiro, R.; Yuki, M.; Sakano, K.; Sasai, M.; Sawada, D.; Ebihara, S.; Hirota, T. Effects of Heat-Treated Lactobacillus helveticus CP790-Fermented Milk on Gastrointestinal Health in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, J.; Wan, Y.; Mair, R.; Price, S.J. Molecular Diversity in Isocitrate Dehydrogenase-Wild-Type Glioblastoma. Brain Commun. 2024, 6, fcae108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Wu, B.; Fu, Z.; Feng, F.; Qiao, E.; Li, Q.; Sun, C.; Ge, M. Prognostic Role of IDH Mutations in Gliomas: A Meta-Analysis of 55 Observational Studies. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 17354–17365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Liu, Y.; Cai, S.J.; Qian, M.; Ding, J.; Larion, M.; Gilbert, M.R.; Yang, C. IDH Mutation in Glioma: Molecular Mecha-Nisms and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 1580–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellinghoff, I.K.; Lu, M.; Wen, P.Y.; Taylor, J.W.; Maher, E.A.; Arrillaga-Romany, I.; Peters, K.B.; Ellingson, B.M.; Rosenblum, M.K.; Chun, S.; et al. Vorasidenib and Ivosidenib in IDH1-Mutant Low-Grade Glioma: A Randomized, Perioperative Phase 1 Trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell Line | Treatment Mode | Cellular Processes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis Stimulation | Necrosis Occurrence | Proliferation Inhibition | |||

| GBa | L. plantarum PM | 0 | 0 | + | |

| L. rhamnosus PM | + | 0 | + | ||

| No postbiotic | TMZ | + | 0 | 0 | |

| ARA12 | + | 0 | + | ||

| irradiation | + | 0 | + | ||

| L. plantarum PM | TMZ | + enh | 0 | + enh | |

| ARA12 | + | 0 | + | ||

| irradiation | + hin | + hin | + | ||

| L. rhamnosus PM | TMZ | + enh | 0 | + enh | |

| ARA12 | + | + hin | + | ||

| irradiation | + hin | + hin | + | ||

| GBb | L. plantarum PM | 0 | 0 | + | |

| L. rhamnosus PM | + | 0 | + | ||

| No postbiotic | TMZ | 0 | 0 | + | |

| ARA12 | + | 0 | + | ||

| irradiation | + | 0 | + | ||

| L. plantarum PM | TMZ | + enh | 0 | + | |

| ARA12 | + | 0 | + | ||

| irradiation | + | 0 | + | ||

| L. rhamnosus PM | TMZ | + enh | 0 | + enh | |

| ARA12 | + | 0 | + | ||

| irradiation | + | 0 | + enh | ||

| GBc | L. plantarum PM | + | 0 | + | |

| L. rhamnosus PM | + | 0 | + | ||

| No postbiotic | TMZ | + | 0 | + | |

| ARA12 | 0 | 0 | + | ||

| irradiation | + | 0 | + | ||

| L. plantarum PM | TMZ | 0 | + | 0 | |

| ARA12 | + enh | 0 | + | ||

| irradiation | + | + hin | + | ||

| L. rhamnosus PM | TMZ | 0 | 0 | + | |

| ARA12 | + enh | 0 | + | ||

| irradiation | 0 | + hin | + | ||

| GBd | L. plantarum PM | 0 | 0 | + | |

| L. rhamnosus PM | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| No postbiotic | TMZ | 0 | 0 | + | |

| ARA12 | + | + | + | ||

| irradiation | + | 0 | + | ||

| L. plantarum PM | TMZ | 0 | 0 | + enh | |

| ARA12 | + | + | + enh | ||

| irradiation | + | 0 | + enh | ||

| L. rhamnosus PM | TMZ | 0 | 0 | + enh | |

| ARA12 | + | + | + enh | ||

| irradiation | + hin | 0 | + enh | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Głowacka, P.; Pudlarz, A.; Wasiak, J.; Peszyńska-Piorun, M.; Biegała, M.; Wiśniewski, K.; Jaskólski, D.J.; Pieczonka, A.M.; Płoszaj, T.; Szemraj, J.; et al. Lactic Acid Bacteria Postbiotics as Adjunctives to Glioblastoma Therapy to Fight Treatment Escape and Protect Non-Neoplastic Cells from Side Effects. Cells 2026, 15, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030226

Głowacka P, Pudlarz A, Wasiak J, Peszyńska-Piorun M, Biegała M, Wiśniewski K, Jaskólski DJ, Pieczonka AM, Płoszaj T, Szemraj J, et al. Lactic Acid Bacteria Postbiotics as Adjunctives to Glioblastoma Therapy to Fight Treatment Escape and Protect Non-Neoplastic Cells from Side Effects. Cells. 2026; 15(3):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030226

Chicago/Turabian StyleGłowacka, Pola, Agnieszka Pudlarz, Joanna Wasiak, Magdalena Peszyńska-Piorun, Michał Biegała, Karol Wiśniewski, Dariusz J. Jaskólski, Adam Marek Pieczonka, Tomasz Płoszaj, Janusz Szemraj, and et al. 2026. "Lactic Acid Bacteria Postbiotics as Adjunctives to Glioblastoma Therapy to Fight Treatment Escape and Protect Non-Neoplastic Cells from Side Effects" Cells 15, no. 3: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030226

APA StyleGłowacka, P., Pudlarz, A., Wasiak, J., Peszyńska-Piorun, M., Biegała, M., Wiśniewski, K., Jaskólski, D. J., Pieczonka, A. M., Płoszaj, T., Szemraj, J., & Witusik-Perkowska, M. (2026). Lactic Acid Bacteria Postbiotics as Adjunctives to Glioblastoma Therapy to Fight Treatment Escape and Protect Non-Neoplastic Cells from Side Effects. Cells, 15(3), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030226