Interleukin-6 in Natural and Pathophysiological Kidney Aging

Abstract

1. Premise

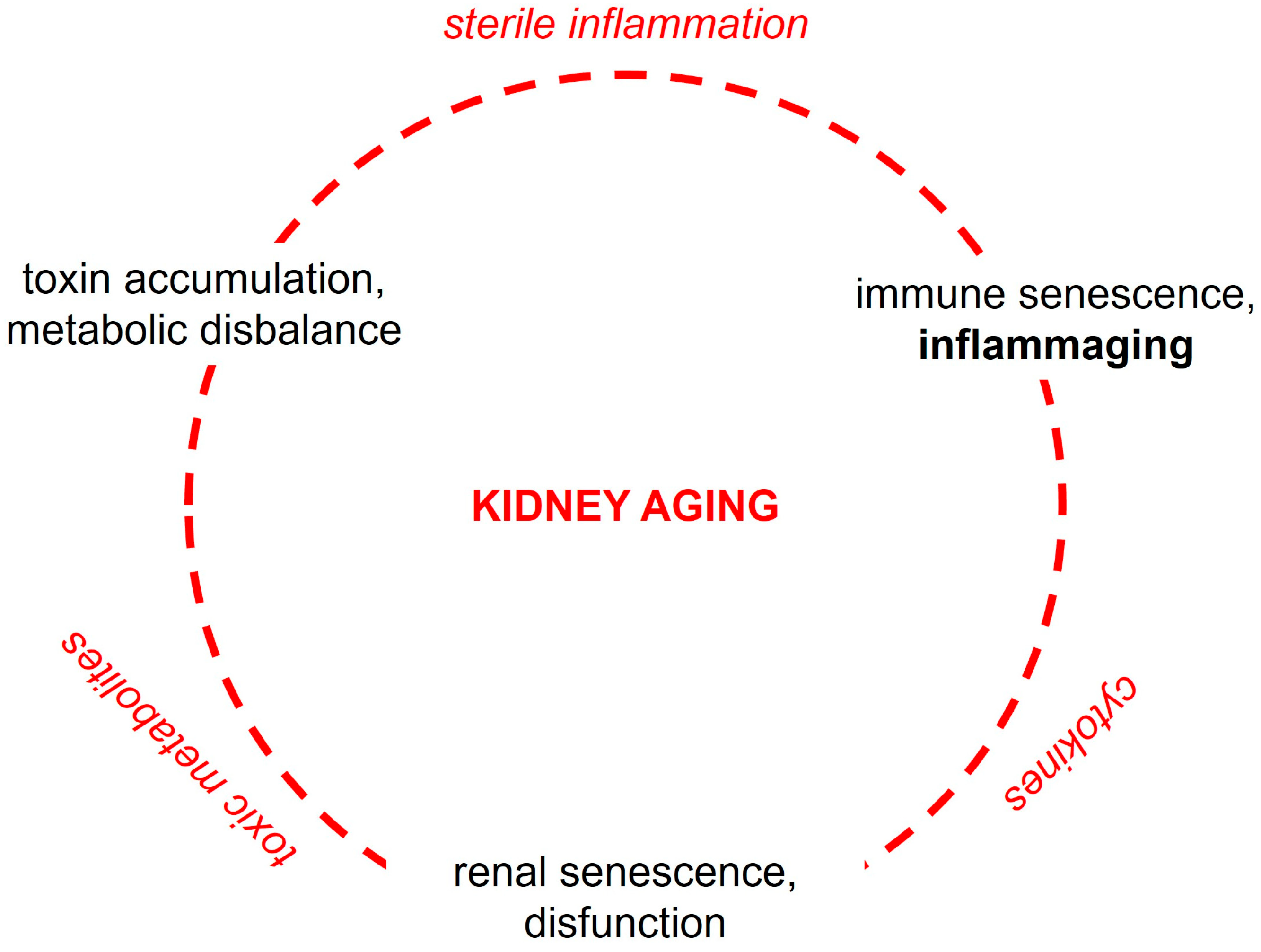

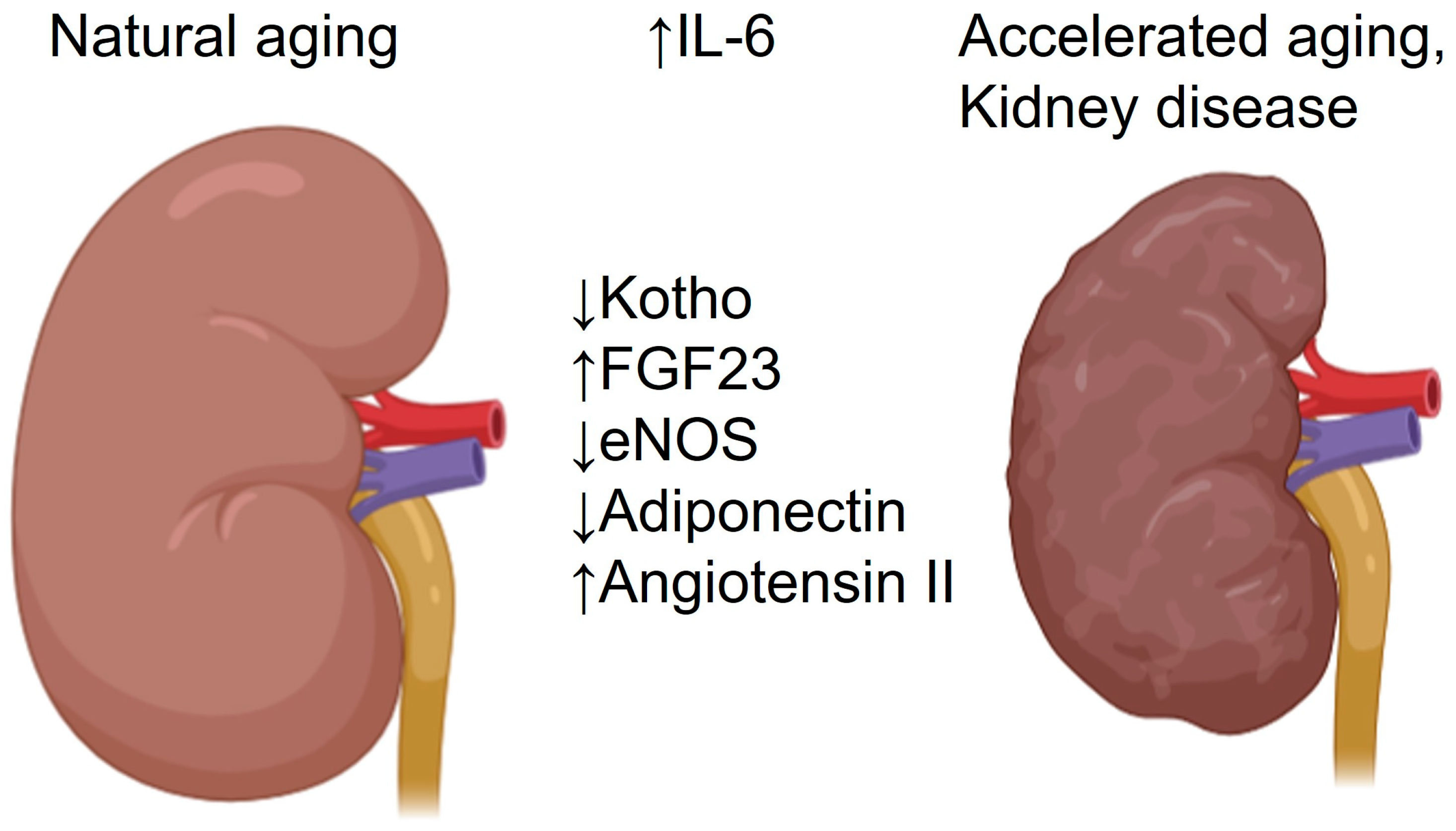

2. Effects of Aging on Kidney Morphology and Function

3. Cell-Biological and Molecular Mechanisms of Kidney Aging

4. Principles of Interleukin-6 Signaling

5. Systemic Interleukin-6 Signaling During Aging

6. Interleukin-6 Signaling in the Aged Kidney

6.1. Glomeruli

6.2. Proximal Tubules

6.3. Distal Nephron and Collecting Ducts

6.4. Renal Vasculature

6.5. Renal Interstitium

6.6. Renal Effects of Interleukin-6 Inhibitors

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kontis, V.; Bennett, J.E.; Mathers, C.D.; Li, G.; Foreman, K.; Ezzati, M. Future Life Expectancy in 35 Industrialised Countries: Projections with a Bayesian Model Ensemble. Lancet 2017, 389, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Du, D. Aging and Chronic Kidney Disease: Epidemiology, Therapy, Management and the Role of Immunity. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of Chronic Kidney Disease: An Update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockwell, P.; Fisher, L.-A. The Global Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2020, 395, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesnaye, N.C.; Ortiz, A.; Zoccali, C.; Stel, V.S.; Jager, K.J. The Impact of Population Ageing on the Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, Y.; Yanagita, M. Healthy Ageing and the Kidney—Lessons from Centenarians. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 558–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommos, M.S.; Glassock, R.J.; Rule, A.D. Structural and Functional Changes in Human Kidneys with Healthy Aging. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 2838–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, E.D.; Hughes, J.; Ferenbach, D.A. Renal Aging: Causes and Consequences. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane-Gill, S.L.; Sileanu, F.E.; Murugan, R.; Trietley, G.S.; Handler, S.M.; Kellum, J.A. Risk Factors for Acute Kidney Injury in Older Adults with Critical Illness: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 65, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, T.; Kitagawa, K.; Oshima, M.; Kitajima, S.; Hara, A.; Iwata, Y.; Sakai, N.; Shimizu, M.; Hashiba, A.; Furuichi, K.; et al. Age Differences in the Relationships between Risk Factors and Loss of Kidney Function: A General Population Cohort Study. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-T.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.-Y.; Huang, J.-W.; Chien, K.-L. Age Modifies the Risk Factor Profiles for Acute Kidney Injury among Recently Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetic Patients: A Population-Based Study. Geroscience 2018, 40, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Gong, A.Y.; Haller, S.T.; Dworkin, L.D.; Liu, Z.; Gong, R. The Ageing Kidney: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 63, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stille, K.; Kribben, A.; Herget-Rosenthal, S. Incidence, Severity, Risk Factors and Outcomes of Acute Kidney Injury in Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Nephrol. 2022, 35, 2237–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coca, S.G.; Cho, K.C.; Hsu, C. Acute Kidney Injury in the Elderly: Predisposition to Chronic Kidney Disease and Vice Versa. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2011, 119, c19–c24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, C.; Vanholder, R.; Massy, Z.A.; Ortiz, A.; Sarafidis, P.; Dekker, F.W.; Fliser, D.; Fouque, D.; Heine, G.H.; Jager, K.J.; et al. The Systemic Nature of CKD. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Woo, K.; Yi, J.A. Epidemiology of End-Stage Kidney Disease. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 34, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmelgarn, B.R.; James, M.T.; Manns, B.J.; O’Hare, A.M.; Muntner, P.; Ravani, P.; Quinn, R.R.; Turin, T.C.; Tan, Z.; Tonelli, M.; et al. Rates of Treated and Untreated Kidney Failure in Older vs Younger Adults. JAMA 2012, 307, 2507–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadban, S.; Arıcı, M.; Power, A.; Wu, M.-S.; Mennini, F.S.; Arango Álvarez, J.J.; Garcia Sanchez, J.J.; Barone, S.; Card-Gowers, J.; Martin, A.; et al. Projecting the Economic Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease at the Patient Level (Inside CKD): A Microsimulation Modelling Study. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 72, 102615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waas, T.; Schulz, A.; Lotz, J.; Rossmann, H.; Pfeiffer, N.; Beutel, M.E.; Schmidtmann, I.; Münzel, T.; Wild, P.S.; Lackner, K.J. Distribution of Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate and Determinants of Its Age Dependent Loss in a German Population-Based Study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeman, R.D.; Tobin, J.; Shock, N.W. Longitudinal Studies on the Rate of Decline in Renal Function with Age. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1985, 33, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Vrtiska, T.J.; Avula, R.T.; Walters, L.R.; Chakkera, H.A.; Kremers, W.K.; Lerman, L.O.; Rule, A.D. Age, Kidney Function, and Risk Factors Associate Differently with Cortical and Medullary Volumes of the Kidney. Kidney Int. 2014, 85, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denic, A.; Lieske, J.C.; Chakkera, H.A.; Poggio, E.D.; Alexander, M.P.; Singh, P.; Kremers, W.K.; Lerman, L.O.; Rule, A.D. The Substantial Loss of Nephrons in Healthy Human Kidneys with Aging. JASN 2017, 28, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule, A.D.; Cornell, L.D.; Poggio, E.D. Senile Nephrosclerosis—Does It Explain the Decline in Glomerular Filtration Rate with Aging? Nephron Physiol. 2011, 119, p6–p11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassock, R.J.; Rule, A.D. Aging and the Kidneys: Anatomy, Physiology and Consequences for Defining Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephron 2016, 134, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-M. Aging and Renal Disease: Old Questions for New Challenges. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, K.L.; Lafayette, R.A. Renal Physiology of Pregnancy. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013, 20, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortmans, J.R.; Vanderstraeten, J. Kidney Function During Exercise in Healthy and Diseased Humans: An Update. Sports Med. 1994, 18, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, J.P.; Saccaggi, A.; Lauer, A.; Ronco, C.; Belledonne, M.; Glabman, S. Renal Functional Reserve in Humans. Am. J. Med. 1983, 75, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jufar, A.H.; Lankadeva, Y.R.; May, C.N.; Cochrane, A.D.; Bellomo, R.; Evans, R.G. Renal Functional Reserve: From Physiological Phenomenon to Clinical Biomarker and Beyond. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2020, 319, R690–R702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, S. Redefining Glomerular Hyperfiltration: Pathophysiology, Clinical Implications, and Novel Perspectives. Hypertens. Res. 2025, 48, 1176–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weijden, J.; Mazhar, F.; Fu, E.L.; van Londen, M.; Evans, M.; Berger, S.P.; De Borst, M.H.; Carrero, J.J. Early Compensatory Increase in Single-Kidney Estimated GFR after Unilateral Nephrectomy Is Associated with a Lower Long-Term Risk of Estimated GFR Decline. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, 1680–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriconi, D.; Sacchetta, L.; Chiriacò, M.; Nesti, L.; Forotti, G.; Natali, A.; Solini, A.; Tricò, D. Glomerular Hyperfiltration Predicts Kidney Function Decline and Mortality in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: A 21-Year Longitudinal Study. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbay, M.; Copur, S.; Bakir, C.N.; Covic, A.; Ortiz, A.; Tuttle, K.R. Glomerular Hyperfiltration as a Therapeutic Target for CKD. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barai, S.; Gambhir, S.; Prasad, N.; Sharma, R.K.; Ora, M. Functional Renal Reserve Capacity in Different Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease: Renal Reserve in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephrology 2010, 15, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Astor, B.C.; Lewis, J.; Hu, B.; Appel, L.J.; Lipkowitz, M.S.; Toto, R.D.; Wang, X.; Wright, J.T.; Greene, T.H. Longitudinal Progression Trajectory of GFR among Patients with CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2012, 59, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Yang, H.-C.; Fogo, A.B. A Perspective on Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2017, 312, F375–F384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliser, D.; Ritz, E.; Franek, E. Renal Reserve in the Elderly. Semin. Nephrol. 1995, 15, 463–467. [Google Scholar]

- Denic, A.; Mathew, J.; Lerman, L.O.; Lieske, J.C.; Larson, J.J.; Alexander, M.P.; Poggio, E.; Glassock, R.J.; Rule, A.D. Single-Nephron Glomerular Filtration Rate in Healthy Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2349–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.B.; Myers, B.D.; Derby, G.; Blouch, K.L.; Yan, J.; Ho, B.; Tan, J.C. Adaptive Hyperfiltration in the Aging Kidney after Contralateral Nephrectomy. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2006, 291, F629–F634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuiano, G.; Sund, S.; Mazza, G.; Rosa, M.; Caglioti, A.; Gallo, G.; Natale, G.; Andreucci, M.; Memoli, B.; De Nicola, L.; et al. Renal Hemodynamic Response to Maximal Vasodilating Stimulus in Healthy Older Subjects. Kidney Int. 2001, 59, 1052–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlanger, L.E.; Bailey, J.L.; Sands, J.M. Electrolytes in the Aging. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010, 17, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowen, L.E.; Hodak, S.P.; Verbalis, J.G. Age-Associated Abnormalities of Water Homeostasis. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. 2013, 42, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershler, W.B.; Sheng, S.; McKelvey, J.; Artz, A.S.; Denduluri, N.; Tecson, J.; Taub, D.D.; Brant, L.J.; Ferrucci, L.; Longo, D.L. Serum Erythropoietin and Aging: A Longitudinal Analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 1360–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathima, O.V.; Shastri, M.; Kotru, M.; Jain, R.; Goel, A.; Sikka, M. Erythropoietin Levels in Geriatric Anemia. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, 4347–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstaedt, R.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Woodman, R.C. Anemia in the Elderly: Current Understanding and Emerging Concepts. Blood Rev. 2006, 20, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erslev, A.J.; Besarab, A. Erythropoietin in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of the Anemia of Chronic Renal Failure. Kidney Int. 1997, 51, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selamet, U.; Katz, R.; Ginsberg, C.; Rifkin, D.E.; Fried, L.F.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Drew, D.; Harris, T.; et al. Serum Calcitriol Concentrations and Kidney Function Decline, Heart Failure, and Mortality in Elderly Community-Living Adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 72, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukas, L.; Schacht, E.; Stähelin, H.B. In Elderly Men and Women Treated for Osteoporosis a Low Creatinine Clearance of <65 Ml/Min Is a Risk Factor for Falls and Fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2005, 16, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Isaka, Y. Pathological Mechanisms of Kidney Disease in Ageing. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Bonafè, M.; Valensin, S.; Olivieri, F.; De Luca, M.; Ottaviani, E.; De Benedictis, G. Inflamm-aging: An Evolutionary Perspective on Immunosenescence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 908, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Pawelec, G.; Khalil, A.; Cohen, A.A.; Hirokawa, K.; Witkowski, J.M.; Franceschi, C. Immunology of Aging: The Birth of Inflammaging. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 64, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.Q.T.; Cho, K.A. Targeting Immunosenescence and Inflammaging: Advancing Longevity Research. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 1881–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: A New Immune–Metabolic Viewpoint for Age-Related Diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, N.; Melk, A.; Schmitt, R. Cellular Senescence and Kidney Aging. Clin. Sci. 2023, 137, 1805–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, R.; Melk, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Renal Aging. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Hickson, L.J.; Eirin, A.; Kirkland, J.L.; Lerman, L.O. Cellular Senescence: The Good, the Bad and the Unknown. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Meng, P.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L. The Relevance of Organelle Interactions in Cellular Senescence. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2445–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, G.; Franzin, R.; Sallustio, F.; Stasi, A.; Banelli, B.; Romani, M.; De Palma, G.; Lucarelli, G.; Divella, C.; Battaglia, M.; et al. Complement Component C5a Induces Aberrant Epigenetic Modifications in Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells Accelerating Senescence by Wnt4/Βcatenin Signaling after Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Aging 2019, 11, 4382–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lerman, L.O. Cellular Senescence: A New Player in Kidney Injury. Hypertension 2020, 76, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wang, P.-H.; Zhang, M.; Du, J.-R. Aging-Related Renal Injury and Inflammation Are Associated with Downregulation of Klotho and Induction of RIG-I/NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Senescence-Accelerated Mice. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.C.; Kuro-o, M.; Moe, O.W. Renal and Extrarenal Actions of Klotho. Semin. Nephrol. 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, G.; An, S.-W.; Al-Juboori, S.I.; Nischan, N.; Yoon, J.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Hilgemann, D.W.; Xie, J.; Luby-Phelps, K.; Kohler, J.J.; et al. Soluble Klotho Binds Monosialoganglioside to Regulate Membrane Microdomains and Growth Factor Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajare, A.D.; Dagar, N.; Gaikwad, A.B. Klotho Antiaging Protein: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential in Diseases. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qian, J.-R.; Li, S.-S.; Liu, Q.-F. Inflammation-Induced Klotho Deficiency: A Possible Key Driver of Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. IJGM 2025, 18, 2507–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-J.; Cai, G.-Y.; Chen, X.-M. Cellular Senescence, Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype, and Chronic Kidney Disease. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 64520–64533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershler, W.B. Interleukin-6: A Cytokine for Gerontolgists. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1993, 41, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylutka, A.; Walas, Ł.; Zembron-Lacny, A. Level of IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β and Age-Related Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1330386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-John, S. Interleukin-6 Family Cytokines. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a028415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, J.; Chaurasia, B.; Goldau, J.; Vogt, M.C.; Ruud, J.; Nguyen, K.D.; Theurich, S.; Hausen, A.C.; Schmitz, J.; Brönneke, H.S.; et al. Signaling by IL-6 Promotes Alternative Activation of Macrophages to Limit Endotoxemia and Obesity-Associated Resistance to Insulin. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Song, H.; Shen, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, J.; Xue, L.; Zhao, F.; Xiao, T.; et al. Functional Role of Skeletal Muscle-Derived Interleukin-6 and Its Effects on Lipid Metabolism. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1110926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Deng, K.-Q.; Lu, C.; Fu, X.; Zhu, Q.; Wan, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Nie, L.; Cai, H.; et al. Interleukin-6 Classic and Trans-Signaling Utilize Glucose Metabolism Reprogramming to Achieve Anti- or pro-Inflammatory Effects. Metabolism 2024, 155, 155832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebenciucova, E.; VanHaerents, S. Interleukin 6: At the Interface of Human Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1255533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, M.; Zohora, F.T.; Anka, A.U.; Ali, K.; Maleknia, S.; Saffarioun, M.; Azizi, G. Interleukin-6 Cytokine: An Overview of the Immune Regulation, Immune Dysregulation, and Therapeutic Approach. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 111, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-P.; Schunck, M.; Kallen, K.-J.; Neumann, C.; Trautwein, C.; Rose-John, S.; Proksch, E. The Interleukin-6 Cytokine System Regulates Epidermal Permeability Barrier Homeostasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2004, 123, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, A.; Faulkner, S.H.; Moir, H.; Warwick, P.; King, J.A.; Nimmo, M.A. Interleukin-6 in Combination with the Interleukin-6 Receptor Stimulates Glucose Uptake in Resting Human Skeletal Muscle Independently of Insulin Action. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2014, 16, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-John, S.; Jenkins, B.J.; Garbers, C.; Moll, J.M.; Scheller, J. Targeting IL-6 Trans-Signalling: Past, Present and Future Prospects. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumertl, T.; Lokau, J.; Rose-John, S.; Garbers, C. Function and Proteolytic Generation of the Soluble Interleukin-6 Receptor in Health and Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Res. 2022, 1869, 119143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millrine, D.; Jenkins, R.H.; Hughes, S.T.O.; Jones, S.A. Making Sense of IL-6 Signalling Cues in Pathophysiology. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heink, S.; Yogev, N.; Garbers, C.; Herwerth, M.; Aly, L.; Gasperi, C.; Husterer, V.; Croxford, A.L.; Möller-Hackbarth, K.; Bartsch, H.S.; et al. Trans-Presentation of IL-6 by Dendritic Cells Is Required for the Priming of Pathogenic TH17 Cells. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Kishimura, M.; Ozaki, S.; Osakada, F.; Hashimoto, H.; Okubo, M.; Murakami, M.; Nakao, K. Cloning of Novel Soluble Gp130 and Detection of Its Neutralizing Autoantibodies in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 106, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, J.R.A.; Smith, S.K.; Wilson, A.; Sharkey, A.M. Soluble Gp130 Is Up-Regulated in the Implantation Window and Shows Altered Secretion in Patients with Primary Unexplained Infertility. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 3953–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wolf, J.; Waetzig, G.H.; Chalaris, A.; Reinheimer, T.M.; Wege, H.; Rose-John, S.; Garbers, C. Different Soluble Forms of the Interleukin-6 Family Signal Transducer Gp130 Fine-Tune the Blockade of Interleukin-6 Trans-Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 16186–16196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamertz, L.; Rummel, F.; Polz, R.; Baran, P.; Hansen, S.; Waetzig, G.H.; Moll, J.M.; Floss, D.M.; Scheller, J. Soluble Gp130 Prevents Interleukin-6 and Interleukin-11 Cluster Signaling but Not Intracellular Autocrine Responses. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, eaar7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungberg, L.U.; Zegeye, M.M.; Kardeby, C.; Fälker, K.; Repsilber, D.; Sirsjö, A. Global Transcriptional Profiling Reveals Novel Autocrine Functions of Interleukin 6 in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 4623107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Q.; Jia, L.; Li, Y.-T.; Farren, T.; Agrawal, S.G.; Liu, F.-T. Increased Autocrine Interleukin-6 Production Is Significantly Associated with Worse Clinical Outcome in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 13994–14006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Lei, C.-T.; Zhang, C. Interleukin-6 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Kidney Disease: An Update. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, A.; Naka, T.; Kubo, M. SOCS Proteins, Cytokine Signalling and Immune Regulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, E.A.; Al-Reesi, I.; Al-Shizawi, N.; Jaju, S.; Al-Balushi, M.S.; Koh, C.Y.; Al-Jabri, A.A.; Jeyaseelan, L. Defining IL-6 Levels in Healthy Individuals: A Meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 3915–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, N.; Sansoni, P.; Girasole, G.; Vescovini, R.; Passeri, G.; Passeri, M.; Pedrazzoni, M. Serum Interleukin-6, Soluble Interleukin-6 Receptor and Soluble Gp130 Exhibit Different Patterns of Age- and Menopause-Related Changes. Exp. Gerontol. 2001, 36, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuliani, G.; Galvani, M.; Maggio, M.; Volpato, S.; Bandinelli, S.; Corsi, A.M.; Lauretani, F.; Cherubini, A.; Guralnik, J.M.; Fellin, R.; et al. Plasma Soluble Gp130 Levels Are Increased in Older Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome. The Role of Insulin Resistance. Atherosclerosis 2010, 213, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Metti, A.L.; Yaffe, K.; Boudreau, R.M.; Ganguli, M.; Lopez, O.L.; Stone, K.L.; Cauley, J.A. Change in Inflammatory Markers and Cognitive Status in the Oldest-Old Women from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechemia-Arbely, Y.; Barkan, D.; Pizov, G.; Shriki, A.; Rose-John, S.; Galun, E.; Axelrod, J.H. IL-6/IL-6R Axis Plays a Critical Role in Acute Kidney Injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuaiter, M.; Axelrod, J.H.; Pizov, G.; Gofrit, O.N. Hyper-Interleukin-6 Protects Against Renal Ischemic-Reperfusion Injury—A Mouse Model. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 605675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vgontzas, A.N.; Bixler, E.O.; Lin, H.-M.; Prolo, P.; Trakada, G.; Chrousos, G.P. IL-6 and Its Circadian Secretion in Humans. Neuroimmunomodulation 2005, 12, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, R.; Bo, M.; Pellegrino, M.; Vezzari, M.; Baldi, M.; Picu, A.; Balbo, M.; Bonelli, L.; Migliaretti, G.; Ghigo, E.; et al. Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Hyperactivity in Human Aging Is Partially Refractory to Stimulation by Mineralocorticoid Receptor Blockade. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 5656–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Morley, J.E. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis and Aging. In Comprehensive Physiology; Terjung, R., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1495–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffey, A.E.; Bergeman, C.S.; Clark, L.A.; Wirth, M.M. Aging and the HPA Axis: Stress and Resilience in Older Adults. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 928–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello-White, R.; Ryff, C.D.; Coe, C.L. Aging and Low-Grade Inflammation Reduce Renal Function in Middle-Aged and Older Adults in Japan and the USA. Age 2015, 37, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicic, R.Z.; Rooney, M.T.; Tuttle, K.R. Diabetic Kidney Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Possibilities. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 2032–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Ning, C.; Tao, L.; Sun, H.; Kellems, R.E.; Blackburn, M.R.; et al. Interleukin 6 Underlies Angiotensin II–Induced Hypertension and Chronic Renal Damage. Hypertension 2012, 59, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamarthi, B.; Williams, G.H.; Ricchiuti, V.; Srikumar, N.; Hopkins, P.N.; Luther, J.M.; Jeunemaitre, X.; Thomas, A. Inflammation and Hypertension: The Interplay of Interleukin-6, Dietary Sodium, and the Renin-Angiotensin System in Humans. Am. J. Hypertens. 2011, 24, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, S.; Korin, B.; Chung, J.-J.; Oxburgh, L.; Shaw, A.S. The Mesangial Cell—the Glomerular Stromal Cell. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satchell, S.C.; Braet, F. Glomerular Endothelial Cell Fenestrations: An Integral Component of the Glomerular Filtration Barrier. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2009, 296, F947–F956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, P. A Review of Podocyte Biology. Am. J. Nephrol. 2018, 47, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moutabarrik, A.; Nakanishi, I.; Ishibashi, M. Interleukin-6 and Interleukin-6 Receptor Are Expressed by Cultured Glomerular Epithelial Cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 1994, 40, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Gu, L.; Yuan, W.; Yu, Q.; Ni, Z.; Ross, M.J.; Kaufman, L.; Xiong, H.; Salant, D.J.; He, J.C.; et al. Podocyte-Specific Deletion of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Attenuates Nephrotoxic Serum–Induced Glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Wolde, J.; Haruhara, K.; Puelles, V.G.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.; Bertram, J.F.; Cullen-McEwen, L.A. The Ability of Remaining Glomerular Podocytes to Adapt to the Loss of Their Neighbours Decreases with Age. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 388, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, J.E.; Goyal, M.; Sanden, S.K.; Wharram, B.L.; Shedden, K.A.; Misek, D.E.; Kuick, R.D.; Wiggins, R.C. Podocyte Hypertrophy, “Adaptation”, and “Decompensation” Associated with Glomerular Enlargement and Glomerulosclerosis in the Aging Rat: Prevention by Calorie Restriction. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 2953–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Eng, D.G.; Kaverina, N.V.; Loretz, C.J.; Koirala, A.; Akilesh, S.; Pippin, J.W.; Shankland, S.J. Global Transcriptomic Changes Occur in Aged Mouse Podocytes. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 1160–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankland, S.J.; Rule, A.D.; Kutz, J.N.; Pippin, J.W.; Wessely, O. Podocyte Senescence and Aging. Kidney360 2023, 4, 1784–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinzie, S.R.; Kaverina, N.; Schweickart, R.A.; Chaney, C.P.; Eng, D.G.; Pereira, B.M.V.; Kestenbaum, B.; Pippin, J.W.; Wessely, O.; Shankland, S.J. Podocytes from Hypertensive and Obese Mice Acquire an Inflammatory, Senescent, and Aged Phenotype. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2024, 326, F644–F660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Su, H.; Ye, C.; Tang, H.; Gao, P.; Wan, C.; He, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. The Classic Signalling and Trans-signalling of Interleukin-6 Are Both Injurious in Podocyte under High Glucose Exposure. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coletta, I.; Soldo, L.; Polentarutti, N.; Mancini, F.; Guglielmotti, A.; Pinza, M.; Mantovani, A.; Milanese, C. Selective Induction of MCP-1 in Human Mesangial Cells by the IL-6/sIL-6R Complex. Exp. Nephrol. 2000, 8, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eitner, F.; Westerhuis, R.; Burg, M.; Weinhold, B.; Gröne, H.-J.; Ostendorf, T.; Rüther, U.; Koch, K.-M.; Rees, A.J.; Floege, J. Role of Interleukin-6 in Mediating Mesangial Cell Proliferation and Matrix Production in Vivo. Kidney Int. 1997, 51, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, S.; Yazdizadeh Shotorbani, P.; Tao, Y.; Davis, M.E.; Mallet, R.T.; Ma, R. Inhibition of Interleukin-6 on Matrix Protein Production by Glomerular Mesangial Cells and the Pathway Involved. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2020, 318, F1478–F1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsterbusch, M.; Hall, P.; Li, A.; Devi, S.; Westhorpe, C.L.V.; Kitching, A.R.; Hickey, M.J. Patrolling Monocytes Promote Intravascular Neutrophil Activation and Glomerular Injury in the Acutely Inflamed Glomerulus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5172–E5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysopoulou, M.; Rinschen, M.M. Metabolic Rewiring and Communication: An Integrative View of Kidney Proximal Tubule Function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2024, 86, 405–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-M.; Yang, L.; Reng, J.; Xu, G.-H.; Zhou, P. Non-Invasive Evaluation of Renal Structure and Function of Healthy Individuals with Multiparametric MRI: Effects of Sex and Age. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacocea, R.I.; Timofte, D.; Tanasescu, M.-D.; Balcangiu-Stroescu, A.-E.; Balan, D.G.; Tulin, A.; Stiru, O.; Vacaroiu, I.A.; Mihai, A.; Popa, C.C.; et al. Kidney Aging Process and the Management of the Elderly Patient with Renal Impairment (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kato, H.; Kojima, I.; Ohse, T.; Son, D.; Tawakami, T.; Yatagawa, T.; Inagi, R.; Fujita, T.; Nangaku, M. Hypoxia and Expression of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor in the Aging Kidney. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006, 61, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemon, Y.; Chick, J.M.; Gerdes Gyuricza, I.; Skelly, D.A.; Devuyst, O.; Gygi, S.P.; Churchill, G.A.; Korstanje, R. Proteomic and Transcriptomic Profiling Reveal Different Aspects of Aging in the Kidney. eLife 2021, 10, e62585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbay, M.; Copur, S.; Ozbek, L.; Mutlu, A.; Cejka, D.; Ciceri, P.; Cozzolino, M.; Haarhaus, M.L. Klotho: A Potential Therapeutic Target in Aging and Neurodegeneration beyond Chronic Kidney Disease—A Comprehensive Review from the ERA CKD-MBD Working Group. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfad276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aging and FGF23-Klotho System. In Vitamins and Hormones; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 115, pp. 317–332.

- Moreno, J.A.; Izquierdo, M.C.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Suárez-Alvarez, B.; Lopez-Larrea, C.; Jakubowski, A.; Blanco, J.; Ramirez, R.; Selgas, R.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; et al. The Inflammatory Cytokines TWEAK and TNFα Reduce Renal Klotho Expression through NFκB. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Andres, O.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Moreno, J.A.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Ramos, A.M.; Sanz, A.B.; Ortiz, A. Downregulation of Kidney Protective Factors by Inflammation: Role of Transcription Factors and Epigenetic Mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2016, 311, F1329–F1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlacher-Betzer, K.; Hassan, A.; Levi, R.; Axelrod, J.; Silver, J.; Naveh-Many, T. Interleukin-6 Contributes to the Increase in Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Expression in Acute and Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2018, 94, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, B.; Faul, C. FGF23 Actions on Target Tissues—With and Without Klotho. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroni, M.Z.; Cendoroglo, M.S.; Costa, A.G.; Marin-Mio, R.V.; do Prado Moreira, P.F.; Maeda, S.S.; Bilezikian, J.P.; Lazaretti-Castro, M. FGF23 Levels as a Marker of Physical Performance and Falls in Community-Dwelling Very Old Individuals. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 66, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Wong, M.; Akhabue, E.; Mehta, R.C.; Kramer, H.; Isakova, T.; Carnethon, M.R.; Wolf, M.; Gutiérrez, O.M. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 and Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in Middle-Aged Adults. JAHA 2021, 10, e020196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, H.; Frazão, J.M. The Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 in Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder. Nefrología 2013, 33, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Crowley, S.D. Renal Effects of Cytokines in Hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2018, 27, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Lasaracina, A.P.; Epps, J.; Ferreri, N.R. TNF Inhibits NKCC2 Phosphorylation by a Calcineurin-Dependent Pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2025, 328, F489–F500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Rudemiller, N.P.; Patel, M.B.; Karlovich, N.S.; Wu, M.; McDonough, A.A.; Griffiths, R.; Sparks, M.A.; Jeffs, A.D.; Crowley, S.D. Interleukin-1 Receptor Activation Potentiates Salt Reabsorption in Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension via the NKCC2 Co-Transporter in the Nephron. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brands, M.W.; Banes-Berceli, A.K.L.; Inscho, E.W.; Al-Azawi, H.; Allen, A.J.; Labazi, H. Interleukin 6 Knockout Prevents Angiotensin II Hypertension: Role of Renal Vasoconstriction and Janus Kinase 2/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Activation. Hypertension 2010, 56, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmat, S.; Rudemiller, N.; Lund, H.; Abais-Battad, J.M.; Van Why, S.; Mattson, D.L. Interleukin-6 Inhibition Attenuates Hypertension and Associated Renal Damage in Dahl Salt-Sensitive Rats. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2016, 311, F555–F561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olauson, H.; Lindberg, K.; Amin, R.; Jia, T.; Wernerson, A.; Andersson, G.; Larsson, T.E. Targeted Deletion of Klotho in Kidney Distal Tubule Disrupts Mineral Metabolism. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 1641–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.; Groen, A.; Molostvov, G.; Lu, T.; Lilley, K.S.; Snead, D.; James, S.; Wilkinson, I.B.; Ting, S.; Hsiao, L.-L.; et al. α-Klotho Expression in Human Tissues. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E1308–E1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuro-o, M.; Matsumura, Y.; Aizawa, H.; Kawaguchi, H.; Suga, T.; Utsugi, T.; Ohyama, Y.; Kurabayashi, M.; Kaname, T.; Kume, E.; et al. Mutation of the Mouse Klotho Gene Leads to a Syndrome Resembling Ageing. Nature 1997, 390, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Pham, T.D.; Su, X.-T.; Grigore, T.V.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Olauson, H.; Wall, S.M.; Ellison, D.H.; Welling, P.A.; Al-Qusairi, L. Klotho Is Highly Expressed in the Chief Sites of Regulated Potassium Secretion, and It Is Stimulated by Potassium Intake. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, W.; Zhang, A.; Jia, Z.; Gu, J.; Chen, H. Klotho Contributes to Pravastatin Effect on Suppressing IL-6 Production in Endothelial Cells. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 2193210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alem, F.; Campos-Obando, N.; Narayanan, A.; Bailey, C.L.; Macaya, R.F. Exogenous Klotho Extends Survival in COVID-19 Model Mice. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taneike, M.; Nishida, M.; Nakanishi, K.; Sera, F.; Kioka, H.; Yamamoto, R.; Ohtani, T.; Hikoso, S.; Moriyama, T.; Sakata, Y.; et al. Alpha-Klotho Is a Novel Predictor of Treatment Responsiveness in Patients with Heart Failure. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Lafuente, L.; Mercado-García, E.; Vázquez-Sánchez, S.; González-Moreno, D.; Boscá, L.; Fernández-Velasco, M.; Segura, J.; Kuro-O, M.; Ruilope, L.M.; Liaño, F.; et al. Interleukin-6 as a Prognostic Marker in Acute Kidney Injury and Its Klotho-Dependent Regulation. Nefrología (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 44, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Núñez, E.; Donate-Correa, J.; Ferri, C.; López-Castillo, Á.; Delgado-Molinos, A.; Hernández-Carballo, C.; Pérez-Delgado, N.; Rodríguez-Ramos, S.; Cerro-López, P.; Tagua, V.G.; et al. Association between Serum Levels of Klotho and Inflammatory Cytokines in Cardiovascular Disease: A Case-Control Study. Aging 2020, 12, 1952–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopp, T.; Jung, R.; Wild, J.; Bochenek, M.L.; Efentakis, P.; Lehmann, A.; Bieler, T.; Garlapati, V.; Richter, C.; Molitor, M.; et al. Myeloid Cell-Derived Interleukin-6 Induces Vascular Dysfunction and Vascular and Systemic Inflammation. Eur. Heart J. Open 2024, 4, oeae046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kishimoto, T. Interplay between Interleukin-6 Signaling and the Vascular Endothelium in Cytokine Storms. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruun, J.M.; Lihn, A.S.; Verdich, C.; Pedersen, S.B.; Toubro, S.; Astrup, A.; Richelsen, B. Regulation of Adiponectin by Adipose Tissue-Derived Cytokines: In Vivo and in Vitro Investigations in Humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 285, E527–E533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.A.; Sakkinen, P.; Conze, D.; Hardin, N.; Tracy, R. Interleukin-6 Exacerbates Early Atherosclerosis in Mice. ATVB 1999, 19, 2364–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, G.; He, L.; Wang, Y. Effect of Interleukin 6 Deficiency on Renal Interstitial Fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Yuan, H.; Cao, W.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Yu, H.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhou, H.; Guo, H.; et al. Blocking Interleukin-6 Trans-Signaling Protects against Renal Fibrosis by Suppressing STAT3 Activation. Theranostics 2019, 9, 3980–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashizume, M.; Hayakawa, N.; Mihara, M. IL-6 Trans-Signalling Directly Induces RANKL on Fibroblast-like Synovial Cells and Is Involved in RANKL Induction by TNF- and IL-17. Rheumatology 2008, 47, 1635–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yin, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, Y. The Role of IL-6 in Fibrotic Diseases: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5405–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubernatorova, E.O.; Samsonov, M.Y.; Drutskaya, M.S.; Lebedeva, S.; Bukhanova, D.; Materenchuk, M.; Mutig, K. Targeting Inerleukin-6 for Renoprotection. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1502299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandran, S.; Leung, J.; Hu, C.; Laszik, Z.G.; Tang, Q.; Vincenti, F.G. Interleukin-6 Blockade with Tocilizumab Increases Tregs and Reduces T Effector Cytokines in Renal Graft Inflammation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 2543–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Aubert, O.; Vo, A.; Loupy, A.; Haas, M.; Puliyanda, D.; Kim, I.; Louie, S.; Kang, A.; Peng, A.; et al. Assessment of Tocilizumab (Anti–Interleukin-6 Receptor Monoclonal) as a Potential Treatment for Chronic Antibody-Mediated Rejection and Transplant Glomerulopathy in HLA-Sensitized Renal Allograft Recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 2381–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokau, J.; Garbers, Y.; Grötzinger, J.; Garbers, C. A Single Aromatic Residue in sgp130Fc/Olamkicept Allows the Discrimination between Interleukin-6 and Interleukin-11 Trans-Signaling. iScience 2021, 24, 103309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.; Aden, K.; Bernardes, J.P.; Conrad, C.; Tran, F.; Höper, H.; Volk, V.; Mishra, N.; Blase, J.I.; Nikolaus, S.; et al. Therapeutic Interleukin-6 Trans-Signaling Inhibition by Olamkicept (sgp130Fc) in Patients With Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 2354–2366.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, B.; Wang, B.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Cao, Q.; Zhong, J.; Shieh, M.-J.; Ran, Z.; Tang, T.; et al. Effect of Induction Therapy With Olamkicept vs Placebo on Clinical Response in Patients With Active Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 329, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.; Bourne, T.; Meier, C.; Carrington, B.; Gelinas, R.; Henry, A.; Popplewell, A.; Adams, R.; Baker, T.; Rapecki, S.; et al. Discovery and Characterization of Olokizumab: A Humanized Antibody Targeting Interleukin-6 and Neutralizing Gp130-Signaling. mAbs 2014, 6, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Natural Kidney Aging | Chronic Kidney Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline GFR | Linear decline ~1 mL/min/1.73 m²/year from the age 30 [25] | Stable or non-linear slow decline until critical nephrons loss, then rapid decline [35,36] |

| Renal functional reserve | Preserved or slightly reduced: ~14–20% up to age 90 [37] | Progressive reduction during disease advancing: 19% → 6.7% (stage 1 → 4) [34] |

| Clinical implications | Renal compensatory capacity is adequate for stressors | Increased risk of acute kidney disease upon stress |

| Cell Type | Adaptive Effects | Maladaptive Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Podocyte | Hypertrophy → compensation of age-related podocyte loss | Decompensation -> podocyte injury | [112] |

| Mesangial cell | ↓ECM production → ↓glomerulosclerosis | Inflammatory response -> glomerular damage | [113,114,115] |

| Proximal and distal tubules | SASP, ↑AngII effect, ↓Klotho, ↑FGF23 -> ↓functionality, electrolyte disbalance, vascular calcification, TIN, accelerated aging | [64,119,120,121,124,125,126,136,139] | |

| Vasculature | Vasoconstriction, leakage -> hypoxia, oxidative stress, inflammation, vascular disease | [134,145,147,148] | |

| Interstitium | Direct and indirect pro-fibrotic effects | [150,151,152] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mutig, K.; Singh, P.B.; Lebedeva, S. Interleukin-6 in Natural and Pathophysiological Kidney Aging. Cells 2026, 15, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030225

Mutig K, Singh PB, Lebedeva S. Interleukin-6 in Natural and Pathophysiological Kidney Aging. Cells. 2026; 15(3):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030225

Chicago/Turabian StyleMutig, Kerim, Prim B. Singh, and Svetlana Lebedeva. 2026. "Interleukin-6 in Natural and Pathophysiological Kidney Aging" Cells 15, no. 3: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030225

APA StyleMutig, K., Singh, P. B., & Lebedeva, S. (2026). Interleukin-6 in Natural and Pathophysiological Kidney Aging. Cells, 15(3), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030225