Targeting SMPDL3B to Ameliorate Radiation- and Cisplatin-Induced Renal Toxicity

Highlights

- Combined radiation + cisplatin reduces podocyte SMPDL3B, driving podocyte loss, GBM thickening, mesangial expansion, fibrosis, albuminuria, and accumulation of long-chain C1P linked to inflammation/cell death.

- Podocyte-specific SMPDL3B overexpression protects kidney structure and function after genotoxic injury and normalizes abnormal C1P accumulation.

- SMPDL3B is a key regulator of podocyte survival and sphingolipid balance during cancer therapy-associated kidney stress, making it a promising target to prevent nephrotoxicity.

- Enhancing SMPDL3B activity/expression may expand the therapeutic window for radiotherapy and platinum chemotherapy, improving tumor control while preserving long-term kidney health.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Study Approval

2.2.2. Animal Housing

2.2.3. Generation of Doxycycline-Inducible, Podocyte-Specific Smpdl3b Overexpressing Mice

2.2.4. Experimental Groups and Treatments

2.2.5. Estimation of Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

2.2.6. Urine Collection and Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio (ACR) Measurement

2.2.7. Blood Sample Analysis

2.2.8. Periodic Acid–Schiff (PAS) Staining and Mesangial Matrix Quantification

2.2.9. Picrosirius Red (PSR) Staining and Quantification of Interstitial Fibrosis

2.2.10. WT1 Immunostaining for Podocyte Quantification

2.2.11. Synaptopodin and SMPDL3B Immunofluorescence Staining and Quantitative Fluorescence Analysis

2.2.12. Ultrastructural Analysis by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.2.13. Targeted Lipidomics

2.2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cisplatin and Radiation Suppress SMPDL3B and Deplete Podocytes in Glomeruli

3.2. Ultrastructural and Functional Renal Damage from Combined Therapy

3.3. SMPDL3B Overexpression Mitigates Radiation-Induced Glomerular Injury

3.4. SMPDL3B Curtails Radiation-Induced Fibrosis and Tubular Damage

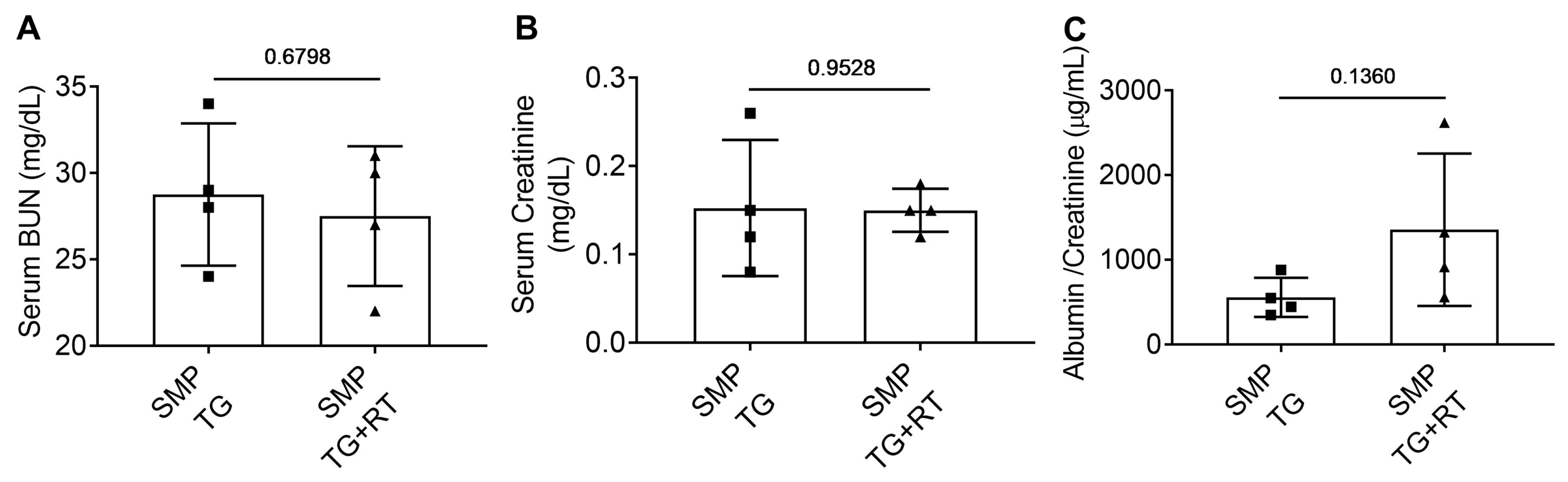

3.5. SMPDL3B Preserves Renal Function Post-Radiation

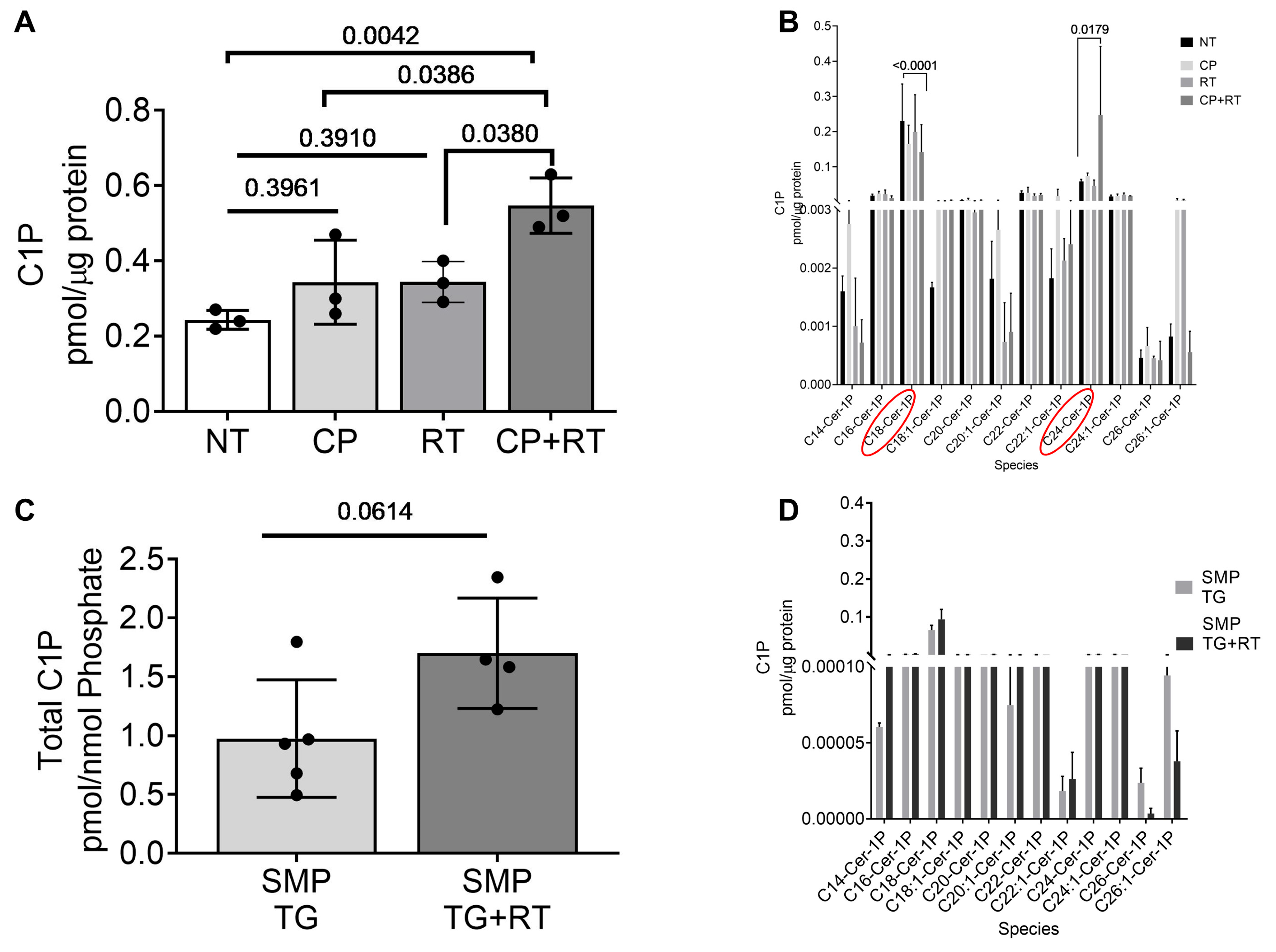

3.6. Radiation and Cisplatin Elevate Ceramide-1-Phosphate (C1P)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kooijmans, E.C.M.; Mulder, R.L.; Marks, S.D.; Pavasovic, V.; Motwani, S.S.; Walwyn, T.; Larkins, N.G.; Kruseova, J.; Constine, L.S.; Wallace, W.H.; et al. Nephrotoxicity Surveillance for Childhood and Young Adult Survivors of Cancer: Recommendations From the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 2433–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, F.; Riboldi, V.; Bruschieri, L.; Villa, A.; Cribiu, F.M.; Borgonovo, K.; Ghilardi, M.; Ghidini, A.; Seghezzi, S.; Stefani, A.; et al. First-line treatment of locally advanced cervical carcinoma: An updated systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2025, 135, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zou, J.; Li, X.; Ge, Y.; He, W. Drug delivery for platinum therapeutics. J. Control. Release 2025, 380, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.E.; Joy, M.S. Understanding Cisplatin Pharmacokinetics and Toxicodynamics to Predict and Prevent Kidney Injury. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2024, 391, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaus, R.; Niyazi, M.; Lange-Sperandio, B. Radiation-induced kidney toxicity: Molecular and cellular pathogenesis. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassier, P.A.; Peyramaure, C.; Attignon, V.; Eberst, L.; Pacaud, C.; Boyault, S.; Desseigne, F.; Sarabi, M.; Guibert, P.; Rochefort, P.; et al. Precision medicine for patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer: A subset analysis of the ProfiLER program. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 15, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, J.N.; McCormick, J.A. Cisplatin-Induced Kidney Injury: Delivering the Goods. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 33, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Dong, Z. Regulation and pathological role of p53 in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 327, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Krishnamurthy, S. Cellular responses to Cisplatin-induced DNA damage. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010, 201367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabla, N.; Dong, Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: Mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, A.F.; Fawzy, A.; Abuhelaiqa, E.; Asim, M.; Nuaman, A.; Ashur, A.; Fituri, O.; Alkadi, M.; Al-Malki, H. Risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease progression: Long-term retrospective analysis from Qatar. Qatar Med. J. 2022, 2022, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, E.E.; Huitema, A.D.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H. Long-term platinum retention after treatment with cisplatin and oxaliplatin. BMC Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ye, Z.W.; Tew, K.D.; Townsend, D.M. Cisplatin chemotherapy and renal function. Adv. Cancer Res. 2021, 152, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, P.; Ying, Y.; Lin, S.; Lu, F.; Gao, C.; Li, M.; Yang, B.; Zhou, H. Mechanisms of Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: The Role of NRF2 in Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Reprogramming. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, G.S.; Kim, H.J.; Shen, A.; Lee, S.B.; Khadka, D.; Pandit, A.; So, H.S. Cisplatin-induced Kidney Dysfunction and Perspectives on Improving Treatment Strategies. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2014, 12, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnukhali, M.; Fornoni, A.; Pollack, A.; Ahmad, A. Lipid Dysregulation in Renal Cancer: Drivers of Tumor Growth and Determinants of Treatment-Induced Toxicity. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2026, 119, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, M.C.; Chuang, P.Y.; He, C.J. The glomerular filtration barrier: Components and crosstalk. Int. J. Nephrol. 2012, 2012, 749010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.J.; Zhu, Y.T.; He, F.F.; Zhang, C. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives of Podocyte Aging in Podocytopathies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrio, R.; Rocha, B.R.A.; Correa, A.; Mascarenhas, M.G.S.; Santos, F.L.; Maia, R.D.H.; Segundo, L.B.; de Almeida, P.A.A.; Moreira, C.M.O.; Sassi, R.H. Chemotherapy-induced acute kidney injury: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Front. Nephrol. 2024, 4, 1436896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimarchi, H. Mechanisms of Podocyte Detachment, Podocyturia, and Risk of Progression of Glomerulopathies. Kidney Dis. 2020, 6, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakic, Z.; Atic, A.; Potocki, S.; Basic-Jukic, N. Sphingolipids and Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, G. Sphingolipid signaling in kidney diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2025, 328, F431–F443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grelle, G.; Cabral, L.M.P.; Almeida, F.G.; Tortelote, G.G.; Garrett, R.; Vieyra, A.; Valverde, R.H.F.; Caruso-Neves, C.; Einicker-Lamas, M. Characterization of Ceramide Kinase from Basolateral Membranes of Kidney Proximal Tubules: Kinetics, Physicochemical Requirements, and Physiological Relevance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, R.J.; Cedeno-Rosario, L.; Maschek, J.A.; Lonergan, T.; Van Vranken, J.G.; Kruse, A.R.S.; Stubben, C.J.; Wang, L.; Stuart, D.; Alcantara, Q.A.; et al. Therapeutic remodeling of the ceramide backbone prevents kidney injury. Cell Metab. 2025, 38, 135–156.E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronner, D.N.; Abuaita, B.H.; Chen, X.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Nunez, G.; He, Y.; Yin, X.M.; O’Riordan, M.X. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Activates the Inflammasome via NLRP3- and Caspase-2-Driven Mitochondrial Damage. Immunity 2015, 43, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M.; Ahmad, A.; Bodgi, L.; Azzam, P.; Youssef, T.; Abou Daher, A.; Eid, A.A.; Fornoni, A.; Pollack, A.; Marples, B.; et al. SMPDL3b modulates radiation-induced DNA damage response in renal podocytes. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, F.; Mandel, A.M.; Blomberg, L.; Wong, M.N.; Chatzinikolaou, G.; Meyer, D.H.; Reinelt, A.; Nair, V.; Akbar-Haase, R.; McCown, P.J.; et al. Loss of genome maintenance is linked to mTOR complex 1 signaling and accelerates podocyte damage. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e172370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrofanova, A.; Fontanella, A.M.; Molina, J.; Zhang, G.; Mallela, S.K.; Severino, L.U.; Santos, J.J.; Tolerico, M.; Njeim, R.; Issa, W.; et al. The enzyme SMPDL3b in podocytes decouples proteinuria from chronic kidney disease progression in experimental Alport Syndrome. Kidney Int. 2025, 108, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Shi, J.; Ansari, S.; Afaghani, J.; Molina, J.; Pollack, A.; Merscher, S.; Zeidan, Y.H.; Fornoni, A.; Marples, B. Noninvasive assessment of radiation-induced renal injury in mice. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2021, 97, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, E.P.; Robbins, M.E. Radiation nephropathy. Semin. Nephrol. 2003, 23, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, L.A.; Kavanagh, B.D.; Paulino, A.C.; Das, S.K.; Miften, M.; Li, X.A.; Pan, C.; Ten Haken, R.K.; Schultheiss, T.E. Radiation-associated kidney injury. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 76, S108–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, A.; Shulhevich, Y.; Geraci, S.; Hesser, J.; Stsepankou, D.; Neudecker, S.; Koenig, S.; Heinrich, R.; Hoecklin, F.; Pill, J.; et al. Transcutaneous measurement of renal function in conscious mice. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2012, 303, F783–F788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schock-Kusch, D.; Geraci, S.; Ermeling, E.; Shulhevich, Y.; Sticht, C.; Hesser, J.; Stsepankou, D.; Neudecker, S.; Pill, J.; Schmitt, R.; et al. Reliability of transcutaneous measurement of renal function in various strains of conscious mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schock-Kusch, D.; Sadick, M.; Henninger, N.; Kraenzlin, B.; Claus, G.; Kloetzer, H.M.; Weiss, C.; Pill, J.; Gretz, N. Transcutaneous measurement of glomerular filtration rate using FITC-sinistrin in rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2009, 24, 2997–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, N.; Boysen, G.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Swenberg, J.A. Tandem mass spectrometry measurements of creatinine in mouse plasma and urine for determining glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int. 2007, 71, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S.D.; Vasievich, M.P.; Ruiz, P.; Gould, S.K.; Parsons, K.K.; Pazmino, A.K.; Facemire, C.; Chen, B.J.; Kim, H.S.; Tran, T.T.; et al. Glomerular type 1 angiotensin receptors augment kidney injury and inflammation in murine autoimmune nephritis. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; El Hindi, S.; Li, J.; Fornoni, A.; Goes, N.; Sageshima, J.; Maiguel, D.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Yap, H.K.; Saleem, M.; et al. Circulating urokinase receptor as a cause of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, G.S. Structural biology of the fibres of the collagenous and elastic systems. Cell Biol. Int. 1996, 20, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, G.N.; Haigh, W.G.; Thorning, D.; Savard, C. Hepatic cholesterol crystals and crown-like structures distinguish NASH from simple steatosis. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, J.; Jauregui, A.N.; Merscher-Gomez, S.; Maiguel, D.; Muresan, C.; Mitrofanova, A.; Diez-Sampedro, A.; Szust, J.; Yoo, T.H.; Villarreal, R.; et al. Podocyte-specific GLUT4-deficient mice have fewer and larger podocytes and are protected from diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 2014, 63, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloy, R.A.; Rogers, S.; Caldon, C.E.; Lorca, T.; Castro, A.; Burgess, A. Partial inhibition of Cdk1 in G 2 phase overrides the SAC and decouples mitotic events. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 1400–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.; Mallela, S.K.; Ansari, S.; Alnukhali, M.; Ali, M.; Merscher, S.; Pollack, A.; Zeidan, Y.H.; Fornoni, A.; Marples, B. Radiation-Induced Nephrotoxicity: Role of Sphingomyelin Phosphodiesterase Acid-like 3b. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2025, 121, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, J.G.; van den Bergh Weerman, M.A.; Assmann, K.J.; Weening, J.J.; Florquin, S. Podocyte foot process effacement is not correlated with the level of proteinuria in human glomerulopathies. Kidney Int. 2004, 66, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Mitrofanova, A.; Bielawski, J.; Yang, Y.; Marples, B.; Fornoni, A.; Zeidan, Y.H. Sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3b mediates radiation-induced damage of renal podocytes. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardellini, S.; Trevisani, F.; Deantoni, C.L.; Paccagnella, M.; Pontara, A.; Floris, M.; Giordano, L.; Caccialanza, R.; Mirabile, A. Nephrotoxicity in locally advanced head and neck cancer: When the end justifies the means to preserve nutritional status during chemoradiation. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 33, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, A.S.; Chopra, S.; Prasad, V. Nephrotoxicity after radionuclide therapies. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 15, 101295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Gao, M.; Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Huang, L.; Liu, Y. Diabetic vascular diseases: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, A.; Koirala, A. Review of the Role of Rituximab in the Management of Adult Minimal Change Disease and Immune-Mediated Focal and Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Glomerular Dis. 2023, 3, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeruschke, S.; Alex, D.; Hoyer, P.F.; Weber, S. Protective effects of rituximab on puromycin-induced apoptosis, loss of adhesion and cytoskeletal alterations in human podocytes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, R.J.; Holland, W.L.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides and Acute Kidney Injury. Semin. Nephrol. 2022, 42, 151281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ahmad, A.; Mallela, S.K.; Ansari, S.; Alnukhali, M.; Merscher, S.; Mitrofanova, A.; Zeidan, Y.H.; Pollack, A.; Fornoni, A.; Marples, B. Targeting SMPDL3B to Ameliorate Radiation- and Cisplatin-Induced Renal Toxicity. Cells 2026, 15, 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020205

Ahmad A, Mallela SK, Ansari S, Alnukhali M, Merscher S, Mitrofanova A, Zeidan YH, Pollack A, Fornoni A, Marples B. Targeting SMPDL3B to Ameliorate Radiation- and Cisplatin-Induced Renal Toxicity. Cells. 2026; 15(2):205. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020205

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmad, Anis, Shamroop Kumar Mallela, Saba Ansari, Mohammed Alnukhali, Sandra Merscher, Alla Mitrofanova, Youssef H. Zeidan, Alan Pollack, Alessia Fornoni, and Brian Marples. 2026. "Targeting SMPDL3B to Ameliorate Radiation- and Cisplatin-Induced Renal Toxicity" Cells 15, no. 2: 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020205

APA StyleAhmad, A., Mallela, S. K., Ansari, S., Alnukhali, M., Merscher, S., Mitrofanova, A., Zeidan, Y. H., Pollack, A., Fornoni, A., & Marples, B. (2026). Targeting SMPDL3B to Ameliorate Radiation- and Cisplatin-Induced Renal Toxicity. Cells, 15(2), 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020205