PD-L1 and BAP1 as Prognostic Biomarkers in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Tissue Samples

2.3. Treatment

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Associations of Clinical Characteristics with Expression of PD-L1 and BAP1

3.3. Associations of Clinical Characteristics with PFS

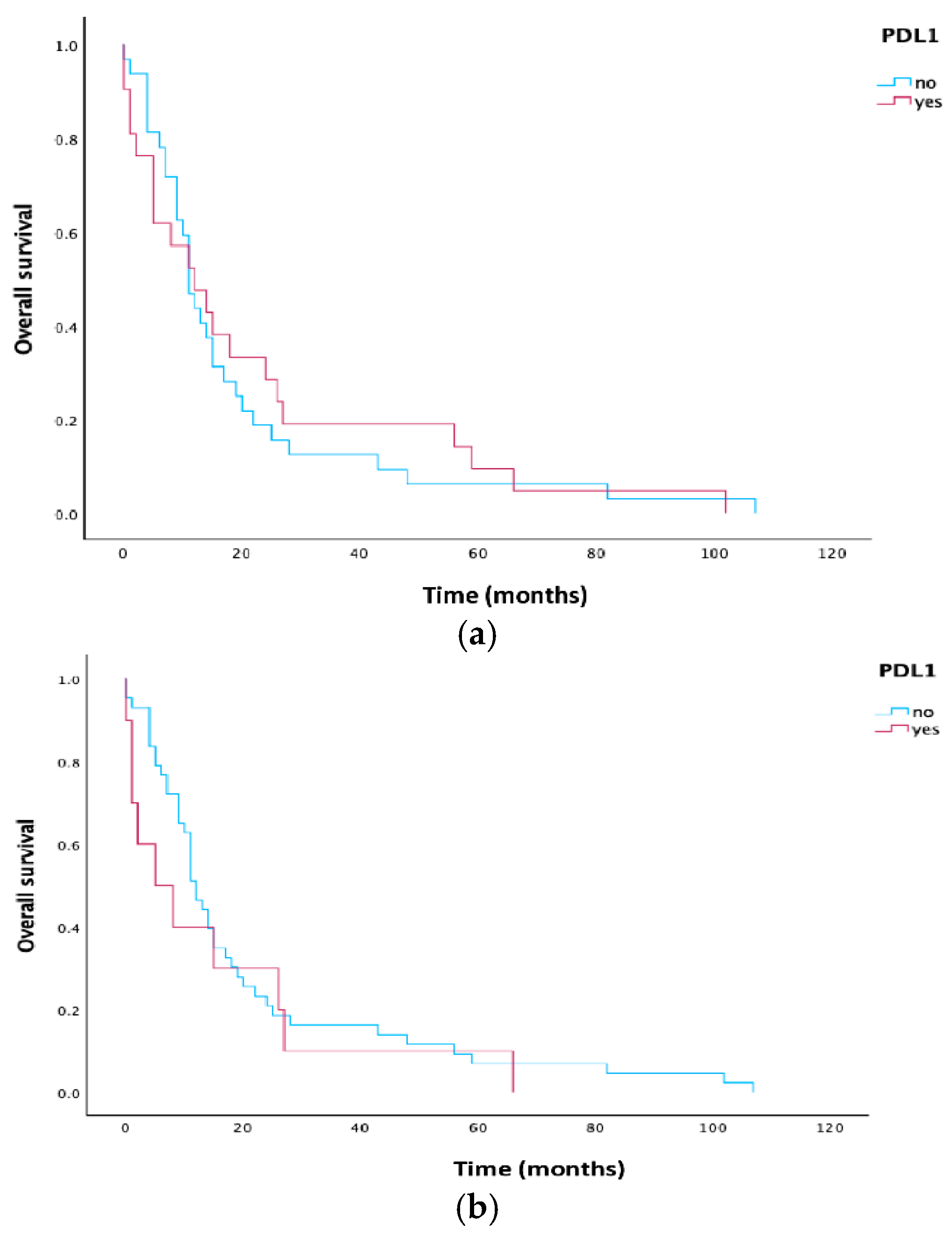

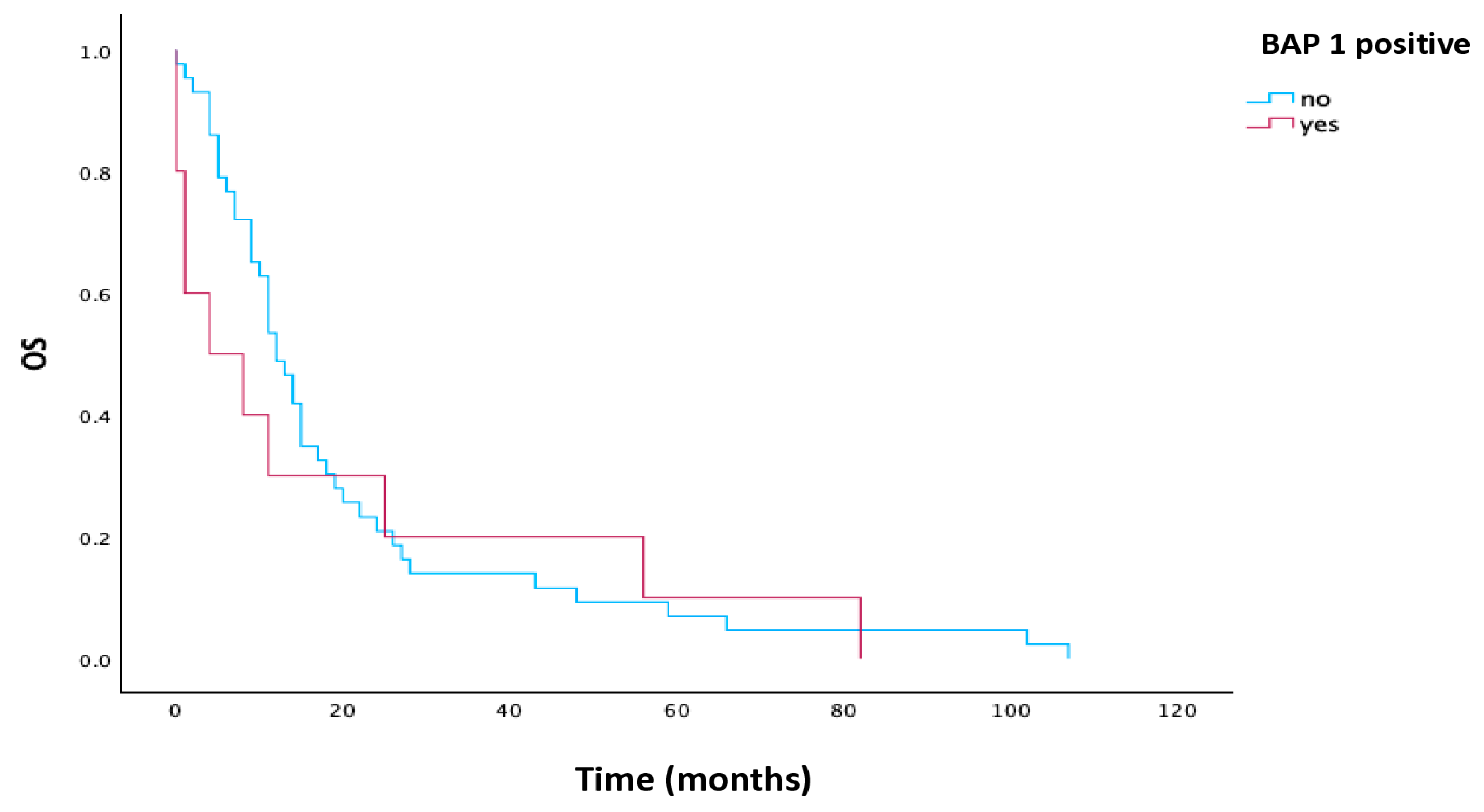

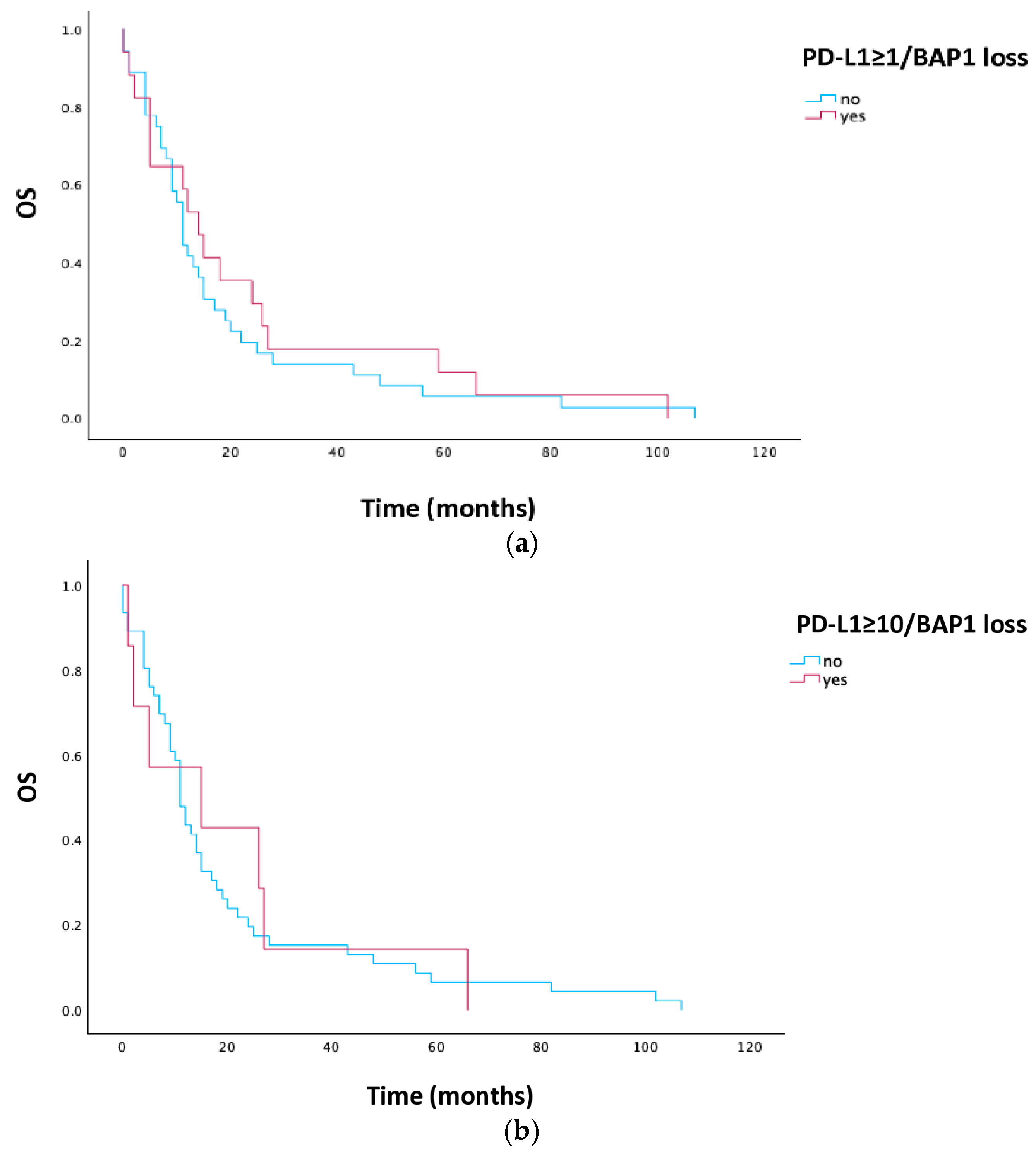

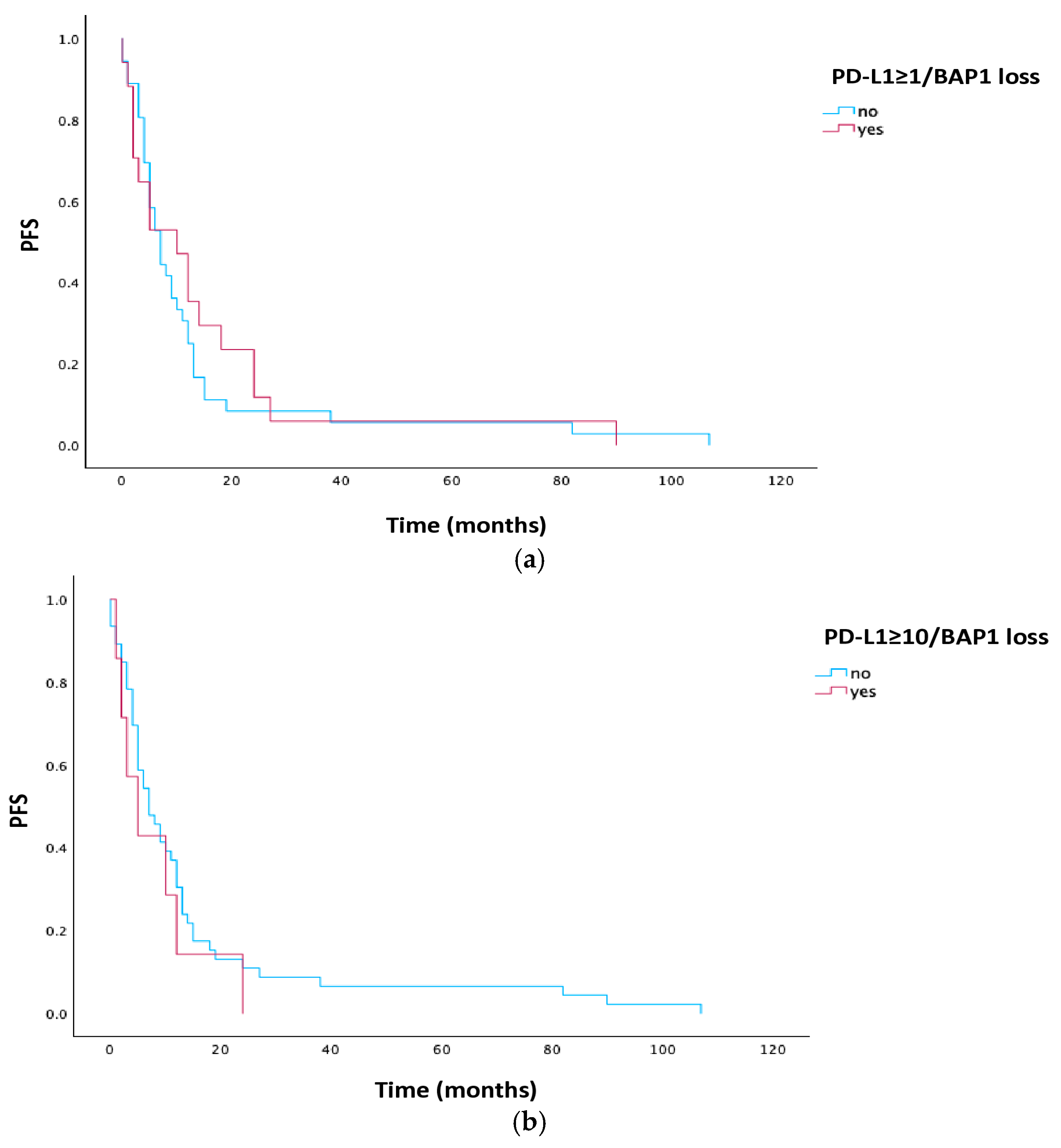

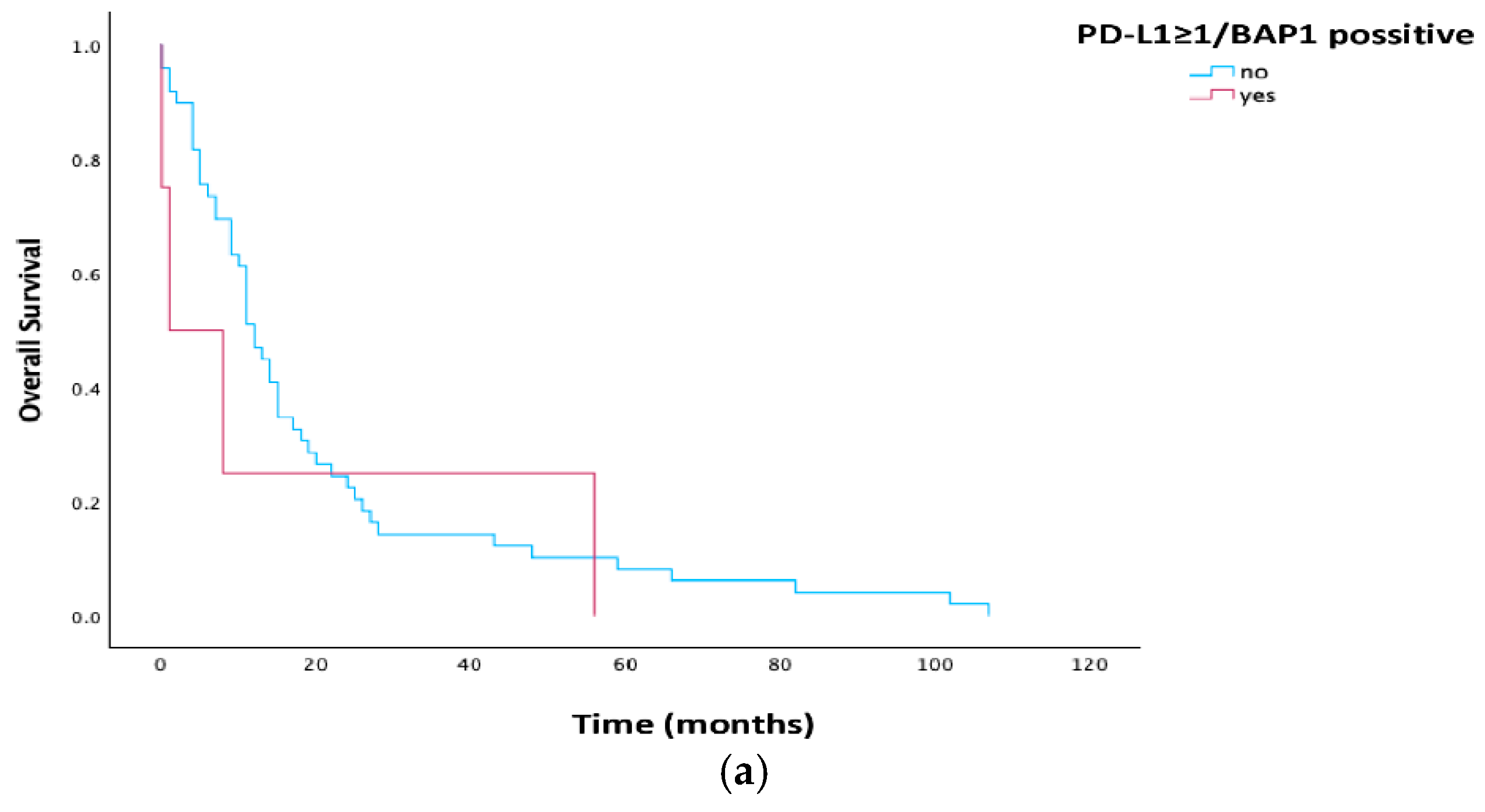

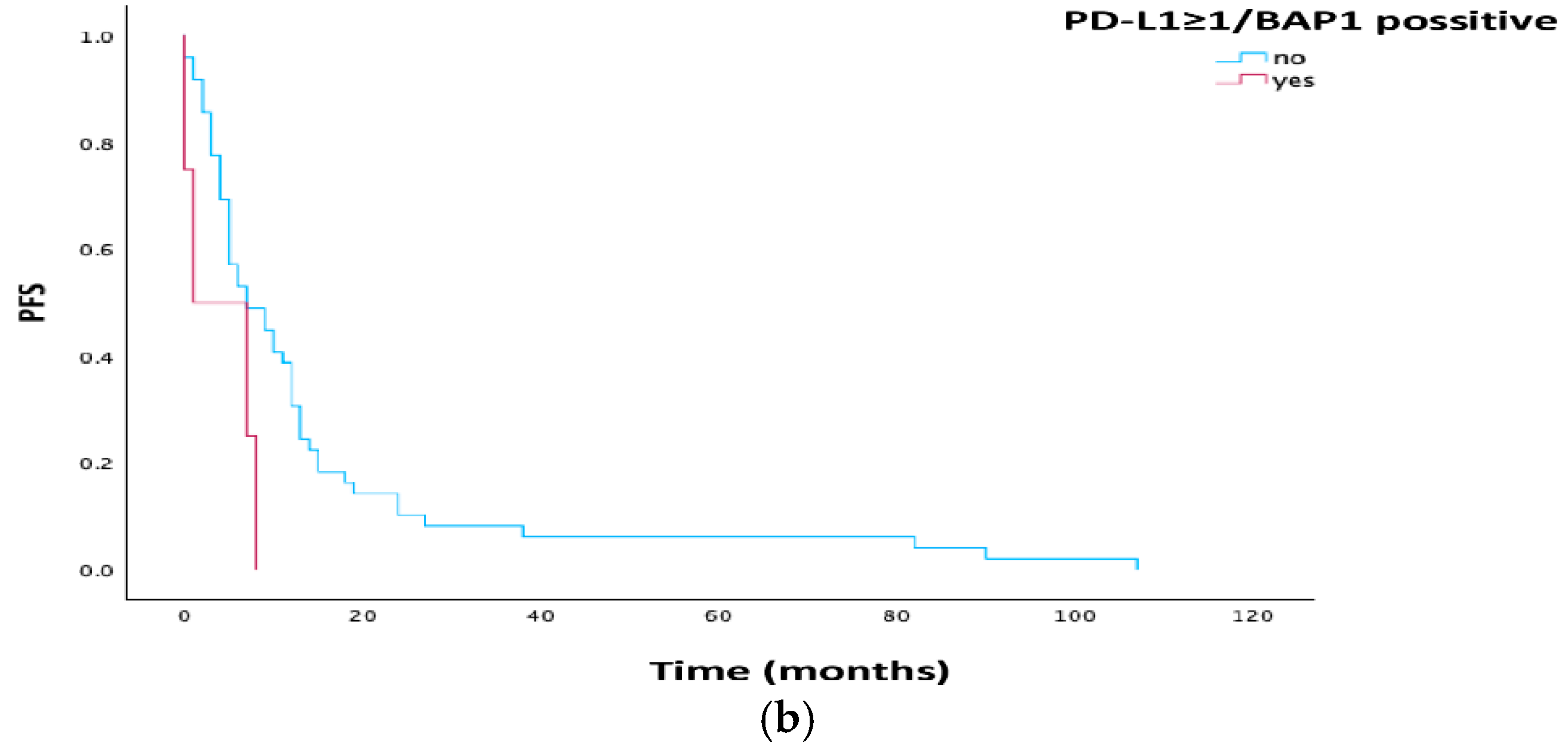

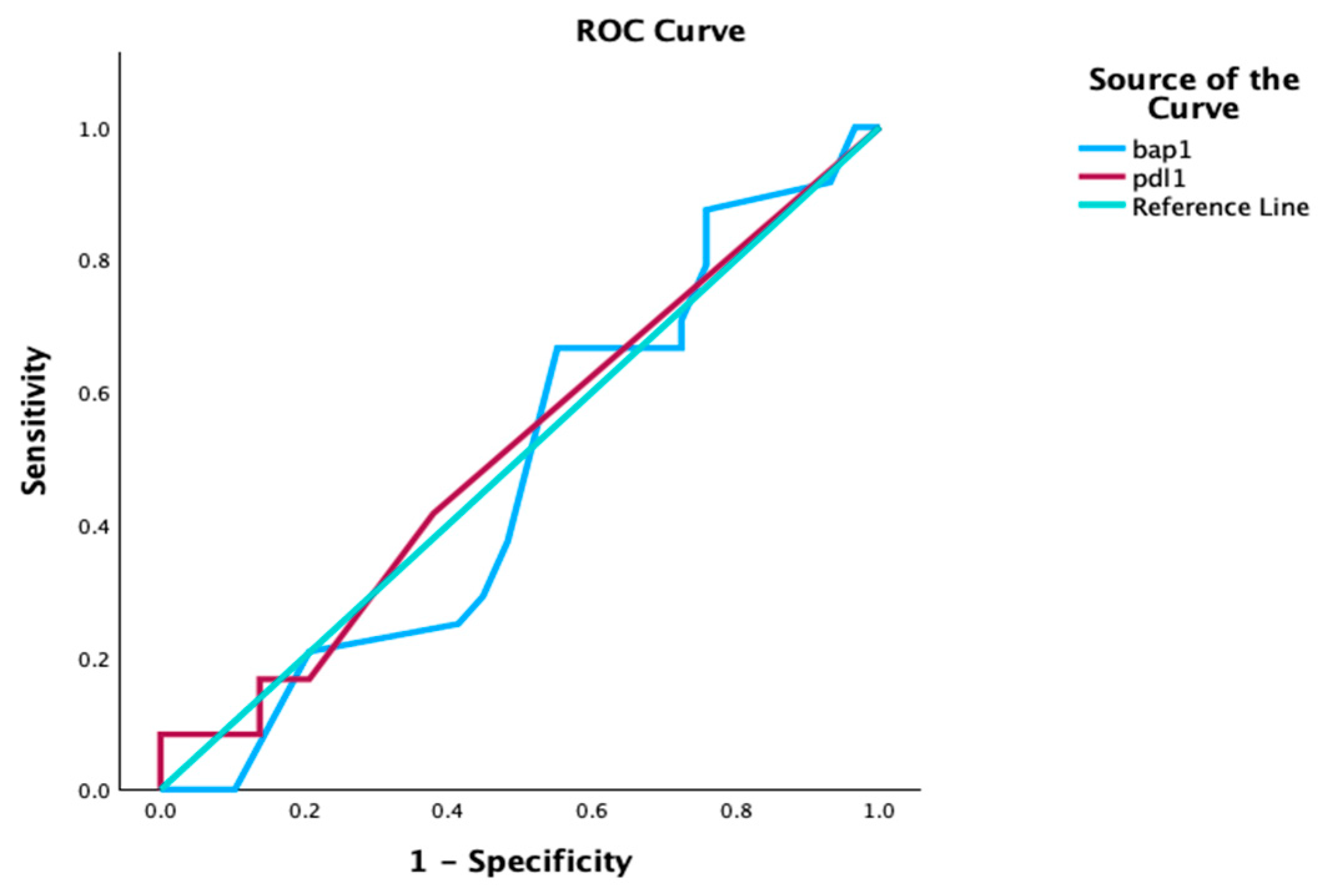

3.4. Survival Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riely, G.J.; Wood, D.E.; Stevenson, J.; Aisner, D.L.; Akerley, W.; Brauman, J.R.; Bharat, A.; Chang, J.Y.; Chirieac, L.R.; DeCamp, M.; et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Mesothelioma: Pleural. Version 1.2025-21 November 2024; National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN): Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenhopp, D.J.; Saliares, A.; Gaduputi, V.; Sunkara, T. An unpleasant surprise: Abdominal presentation of malignant mesothelioma. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2020, 8, 2324709620950121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakiroglu, E.; Senturk, S. Genomics and functional genomics of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman-Casta, J.; Carrasco-CaraChards, S.; Guzman-Hesca, J.; Sanchez-Rios, C.P.; Riera-Sala, R.; Martinez-Herrera, J.F.; Pena-Mirabal, E.S.; Bonilla-Molina, D.; Alatorre-Alexander, J.A.; Martinez-Barrera, L.M.; et al. Prognostic factors for progression-free and overall survival in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quetel, L.; Meiller, C.; Assie, J.B.; Blum, Y.; Imbeaud, S.; Montagne, F.; Tranchant, R.; De Wolt, J.; Caruso, S.; Copin, M.C.; et al. Genetic alterations of malignant pleural mesothelioma: Association with tumor heterogeneity and overall survival. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1207–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janosilkova, M.; Nakladalova, M.; Stepanek, L. Current causes of mesothelioma: How has the asbestos ban changed the perspective? Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Polacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2023, 167, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, E.; Bosch-Barrera, J.; Cedrés, S.; Coves, J.; García-Campelo, R.; Guirado, M.; López-Castro, R.; Ortega, A.L.; Vicente, D.; de Castro-Carpeño, J. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma (2020). Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 23, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remon, J.; Handriks, L.E.L.; Bironzo, P. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: New guidelines make us stronger for defeating this disease. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metro, G.; Signorelli, D.; Pizzutilo, E.G.; Giannetta, L.; Cerea, G.; Garaffa, M.; Friedlaender, A.; Addeo, A.; Mandarano, M.; Bellezza, G.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 2972–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Song, Z.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. Chinese expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Thorac. Cancer 2023, 14, 2715–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Gu, W.; Li, X.; Xie, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z. PD-L1 and prognosis in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: A meta-analysis and bioinformatics study. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, K.; Fujimoto, N. Current evidence and future perspectives of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacic, S. Pleural mesothelioma classification-update and challenges. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadowski, B.; De Rienzo, A.; Bueno, R. The molecular basis of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2020, 30, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, A.G.; Saute, J.L.; Nowak, A.K.; Kindler, H.L.; Gill, R.R.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Armato, S.G., III; Fernandez-Cuesta, L.; Bueno, R.; Alcala, N.; et al. EURACAN/IASLC Proposals for updating the histologic classification of pleural mesothelioma: Towards a More Multidisciplinary Approach. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rienzo, A.; Chirieac, L.R.; Hung, Y.P.; Severson, D.T.; Freyaldenhoven, S.; Gustafson, C.E.; Dao, N.T.; Meyerovitz, C.; Oster, M.E.; Jansen, R.V.; et al. Large-scale analysis of BAP1 expression reveals novel associations with clinical and molecular features of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J. Pathol. 2021, 253, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yao, F.; Peng, R.W. Revisiting “BAP1ness” in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savic, I.; Myers, J. Update on diagnosing and reporting malignant pleural mesothelioma. Acta Medica Acad. 2021, 50, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, A.; Creaney, J. Genomic Landscape of pleural mesothelioma and therapeutic aftermaths. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcaid, L.; Bertelsen, B.; Wadt, K.; Tuxen, I.; Spanggaard, I.; Hojgaard, M.; Sorensen, J.B.; Ravn, J.; Lassen, U.; Nielsen, C.; et al. New pathogenic germline variants identified in mesothelioma. Lung Cancer 2023, 179, 107172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviles-Salas, A.; Cabrera-Miranda, L.; Hernandez-Pedro, N.; Vargas-Lias, D.S.; Samtani, S.; Munoz-Montano, W.; Motola-Kuba, D.; Corrales-Rodriguez, L.; Martin, C.; Cardona, A.F.; et al. PD-L1 expression complements CALGB prognostic scoring system in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1269029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illini, O.; Benej, M.; Lang-Stoberl, A.S.; Fabikan, H.; Brcic, L.; Sucher, F.; Krenbek, D.; Krajic, T.; Weinlinger, C.; Hochmair, M.J.; et al. Prognostic value of PD-L1 and BAP-1 and ILK in pleural mesothelioma. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brcic, L.; Klikovits, T.; Megyesfalvi, Z.; Mosleh, B.; Sinn, K.; Hritcu, R.; Laszlo, V.; Cufer, T.; Rozman, A.; Kern, I.; et al. Prognostic impact of PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in malignant pleural mesothelioma: An international multicenter study. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1594–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laet, C.; Domen, A.; Cheung, K.J.; Meulemans, E.; Lauwers, P.; Hendriks, J.M.; Van Schil, P.E. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: Rationale for a new TNM classification. Acta Chir. Belgica 2014, 114, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlar Dursun, F.S.; Alabalik, U. Investigation of PD-L1 (cd 274), PD-L2 (pdcd1lg2), and CTLA-4 expressions in malignant pleural mesothelioma by immunohistochemistry and real-time polymerase chain reaction methods. Pol. J. Pathol. 2022, 73, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, A.S.; Brown, R.J.; Sammon, C.; Daumont, M.J.; McKenna, M.; Sanzaric, J.K.; Forde, P.M. The predictive and prognostic nature of programmed death-ligand 1 in malignant pleural mesothelioma: A systematic literature review. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2022, 3, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzuto, F.; Vimercati, L.; Fortarezza, F.; Marzullo, A.; Pennella, A.; Cavone, D.; Punzi, A.; Caporusso, C.; D’aMati, A.; Lettini, T.; et al. Evaluation of prognostic histological parameters proposed for pleural mesothelioma in diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. A short report. Diagn. Pathol. 2021, 16, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, B.; Rosenmayr, A.; Stockhammer, P.; Vogl, M.; Celik, A.; Bas, A.; Curneyt Kurul, I.; Akyurek, N.; Varga, A.; Plones, T.; et al. Tumour cell PD-L1 expression is prognostic in patients with malignant pleural effusion: The impact of C-reactive protein and immune-checkpoint inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cedres, S.; Assaf, J.D.; Iranzo, P.; Callejo, A.; Pardo, N.; Navarro, A.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Marmolejo, D.; Razquallah, A.; Carbonell, C.; et al. Efficacy of chemotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma according to histology in a real-world cohort. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combaz-Lair, C.; Galateau-Sallé, F.; McLeer-Florin, A.; Le Stang, N.; David-Boudet, L.; Duruisseaux, M.; Ferretti, G.R.; Brambilla, E.; Lebecque, S.; Lantuejoul, S. Immune biomarkers PD-1/PD-L1 and TLR3 in malignant pleural mesotheliomas. Hum. Pathol. 2016, 52, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedrés, S.; Ponce-Aix, S.; Zugazagoitia, J.; Sansano, I.; Enguita, A.; Navarro-Mendivil, A.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Martinez, P.; Felip, E. Analysis of Expression of Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1 (PD-L1) in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MPM). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosseau, S.; Danel, C.; Scherpereel, A.; Mazières, J.; Lantuejoul, S.; Margery, J.; Greillier, L.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Gounant, V.; Antoine, M.; et al. Shorter Survival in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Patients With High PD-L1 Expression Associated With Sarcomatoid or Biphasic Histology Subtype: A Series of 214 Cases From the Bio-MAPS Cohort. Clin. Lung Cancer 2019, 20, e564–e575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.Y.; Shi, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.G.; Zhang, Z.G. Clinical significance of 9P21 gene combined with BAP1 and MTAP protein expression in diagnosis and prognosis of mesothelioma serous effusion. Biomed. Rep. 2022, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapel, D.B.; Hornick, J.L.; Barlow, J.; Bueno, R.; Sholl, L.M. Clinical and molecular validation of BAP1, MTAP, P53 and Merlin immunohistochemistry in diagnosis of pleural mesothelioma. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 1383–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedres, S.; Valdivia, A.; Priano, I.; Rocha, P.; Iranzo, P.; Pardo, N.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Felip, E. BAP1 mutations and pleural mesothelioma: Genetic insights, clinical implications and therapeutic perspectives. Cancers 2025, 17, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| ≥65 | 32 | 60.4 |

| <65 | 21 | 39.6 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 37 | 69.8 |

| Female | 16 | 30.2 |

| Histology | ||

| Epitheloid | 41 | 77.4 |

| Bifasic | 2 | 3.8 |

| MM | 4 | 7.5 |

| Sarcomatoides | 6 | 11.3 |

| Stage | ||

| Early (I/II) | 37 | 69.8 |

| Late (III/IV) | 16 | 30.2 |

| Treatment | ||

| CHT | 32 | 60.4 |

| Surgery | 1 | 1.9 |

| MMT | 8 | 15.1 |

| BSC | 12 | 22.6 |

| PS | ||

| 0–1 | 46 | 86.8 |

| 2–3 | 7 | 13.2 |

| PD-L1 | ||

| TPS < 1% | 32 | 60.4 |

| TPS ≥ 1% | 21 | 39.6 |

| TPS < 10% | 43 | 81.1 |

| TPS ≥ 10% | 10 | 18.9 |

| BAP1 | ||

| Loss | 43 | 81.1 |

| Positive | 10 | 18.9 |

| PD-L1 | PD-L1 | BAP1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1% | ≥1% | <10% | ≥10% | Loss | Positive | |

| Age (N, %) | ||||||

| ≥65 | 17 (53.1) | 15 (71.4) | 27 (62.8) | 5 (50.0) | 26 (60.5) | 4 (40.0) |

| <65 | 15 (46.9) | 6 (28.6) | 16 (37.2) | 5 (50.0) | 17 (39.5) | 6 (60.0) |

| p = 0.183 | p = 0.492 | p = 1.000 | ||||

| Sex (N, %) | ||||||

| Male | 22 (68.8) | 15 (71.4) | 29 (67.4) | 8 (80.29) | 29 (67.4) | 8 (80.0) |

| Female | 10 (31.3) | 6 (28.6) | 14 (32.6) | 2 (20.2) | 14 (32.6) | 2 (20.0) |

| p = 0.835 | p = 0.704 | p = 0.704 | ||||

| Histology (N, %) | ||||||

| Epitheloid | 26 (81.3) | 15 (71.4) | 35 (81.4) | 6 (60.0) | 34 (79.1) | 7 (70.0) |

| Bifasic | 1 (3.1) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| MM | 4 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sarcomatoides | 1 (3.1) | 5 (23.8) | 3 (7.0) | 3 (30.3) | 3 (7.0) | 3 (30.0) |

| p = 0.033 | p = 0.087 | p = 0.180 | ||||

| Stage (N, %) | ||||||

| Early (I/II) | 23 (71.9) | 14 (66.7) | 33 (76.7) | 4 (40.0) | 33 (76.7) | 4 (40.0) |

| Late (III/IV) | 9 (28.1) | 7 (33.3) | 10 (23.3) | 6 (60.0) | 10 (23.3) | 6 (60.0) |

| p = 0.686 | p = 0.050 | p = 0.050 | ||||

| Treatment (N, %) | ||||||

| CHT | 21 (65.6) | 11 (52.4) | 29 (67.4) | 3 (30.0) | 25 (58.1) | 7 (70.0) |

| Surgery | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.89) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| MMT | 4 (12.5) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (9.3) | 4 (40.0) | 8 (18.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| BSC | 7 (21.9) | 5 (23.8) | 9 (20.9) | 3 (30.0) | 9 (20.9) | 3 (30.0) |

| p = 0.551 | p = 0.041 | p = 0.489 | ||||

| PS (N, %) | ||||||

| 0–1 | 29 (90.6) | 17 (81.0) | 29 (90.6) | 17 (81.0) | 39 (90.7) | 7 (70.0) |

| 2–3 | 3 (9.4) | 4 (19.0) | 3 (9.4) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (9.3) | 3 (30.0) |

| p = 0.415 | p = 0.415 | p = 0.114 | ||||

| PFS | 95.0% CI | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median | Lower | Upper | ||

| Age | 0.477 | ||||

| ≥65 | 32 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 13.0 | |

| <65 | 21 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 12.0 | |

| Sex | 0.831 | ||||

| Male | 37 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 12.0 | |

| Female | 16 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 13.0 | |

| Histology | 0.008 | ||||

| Epitheloid | 41 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 12.0 | |

| Bifasic | 2 | 13.5 | 12.0 | 15.0 | |

| MM | 4 | 10.5 | 7.0 | 13.0 | |

| Sarcomatoides | 6 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 7.0 | |

| Stage | 0.034 | ||||

| Early (I/II) | 37 | 9.0 | 5.0 | 12.0 | |

| Late (III/IV) | 16 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 13.0 | |

| Treatment | 0.345 | ||||

| CHT | 32 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 11.0 | |

| Surgery | 1 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| MMT | 8 | 13.5 | 3.0 | 24.0 | |

| BSC | 12 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 13.0 | |

| PS | 0.042 | ||||

| 0–1 | 46 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 12.0 | |

| 2–3 | 7 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 90.0 | |

| PD-L1 | |||||

| TPS < 1% | 32 | 7.0 | 3.311 | 10.689 | 0.860 |

| TPS ≥ 1% | 21 | 7.0 | 1.393 | 12.607 | |

| TPS < 10% | 43 | 7.0 | 3.145 | 10.855 | 0.100 |

| TPS ≥ 10% | 10 | 3.0 | 0.000 | 7.649 | |

| BAP1 | |||||

| Loss | 43 | 9.0 | 4.726 | 13.274 | 0.264 |

| Positive | 10 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 10.198 | |

| OS | 95.0% CI | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median | Lower | Upper | ||

| Age | |||||

| ≥65 | 32 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 17.0 | 0.856 |

| <65 | 21 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 19.0 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 37 | 11.0 | 9.0 | 15.0 | 0.816 |

| Female | 16 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 18.0 | |

| Histology | |||||

| Epitheloid | 41 | 12.0 | 9.0 | 19.0 | 0.045 |

| Bifasic | 2 | 20.5 | 15.0 | 26.0 | |

| MM | 4 | 11.5 | 9.0 | 13.0 | |

| Sarcomatoides | 6 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 56.0 | |

| Stage | |||||

| Early (I/II) | 37 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 20.0 | 0.049 |

| Late (III/IV) | 16 | 9.5 | 2.0 | 14.0 | |

| Treatment | 0.002 | ||||

| CHT | 32 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 20.0 | |

| Surgery | 1 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| MMT | 8 | 26.5 | 15.0 | 66.0 | |

| BSC | 12 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 13.0 | |

| PS | |||||

| 0–1 | 46 | 12.5 | 11.0 | 17.0 | |

| 2–3 | 7 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 102.0 | |

| PD-L1 | |||||

| TPS < 1% | 32 | 11.0 | 8.787 | 13.213 | 0.799 |

| TPS ≥ 1% | 21 | 12.0 | 3.028 | 20.972 | |

| TPS < 10% | 43 | 12.0 | 9.596 | 14.404 | 0.464 |

| TPS ≥ 10% | 10 | 5.0 | 0.000 | 14.297 | |

| BAP1 | |||||

| Loss | 43 | 12.0 | 9.145 | 14.855 | 0.541 |

| Positive | 10 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 14.847 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gajić, M.; Ćeriman Krstić, V.; Samardžić, N.; Soldatović, I.; Glumac, S.; Jovanović, M.; Savić, M.; Stjepanović, M.; Popević, S.; Stević, R.; et al. PD-L1 and BAP1 as Prognostic Biomarkers in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Cells 2026, 15, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020183

Gajić M, Ćeriman Krstić V, Samardžić N, Soldatović I, Glumac S, Jovanović M, Savić M, Stjepanović M, Popević S, Stević R, et al. PD-L1 and BAP1 as Prognostic Biomarkers in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Cells. 2026; 15(2):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020183

Chicago/Turabian StyleGajić, Milija, Vesna Ćeriman Krstić, Natalija Samardžić, Ivan Soldatović, Sofija Glumac, Milena Jovanović, Milan Savić, Mihailo Stjepanović, Spasoje Popević, Ruža Stević, and et al. 2026. "PD-L1 and BAP1 as Prognostic Biomarkers in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma" Cells 15, no. 2: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020183

APA StyleGajić, M., Ćeriman Krstić, V., Samardžić, N., Soldatović, I., Glumac, S., Jovanović, M., Savić, M., Stjepanović, M., Popević, S., Stević, R., Čolić, N., Lukić, K., Milenković, V., Milivojević, I., Radovanović, I. S., & Jovanović, D. (2026). PD-L1 and BAP1 as Prognostic Biomarkers in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Cells, 15(2), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020183