Tracking Systemic and Ocular Vitamin A

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice

2.2. Diets and Vitamin A Intake

2.3. Fundus Imaging

2.4. Measurement of Retinoids

2.5. Quantitation of Bisretinoids HPLC and UPLC

2.6. Histology

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Retinoid Levels in Plasma and Liver

3.2. Ocular Retinoid Varies with Vitamin A Intake: Dark-Rearing

3.3. Ocular Retinoid Varies with Vitamin A Intake: Cyclic Light-Rearing

3.4. Retinoid Levels in Light- Versus Dark-Adapted Mice

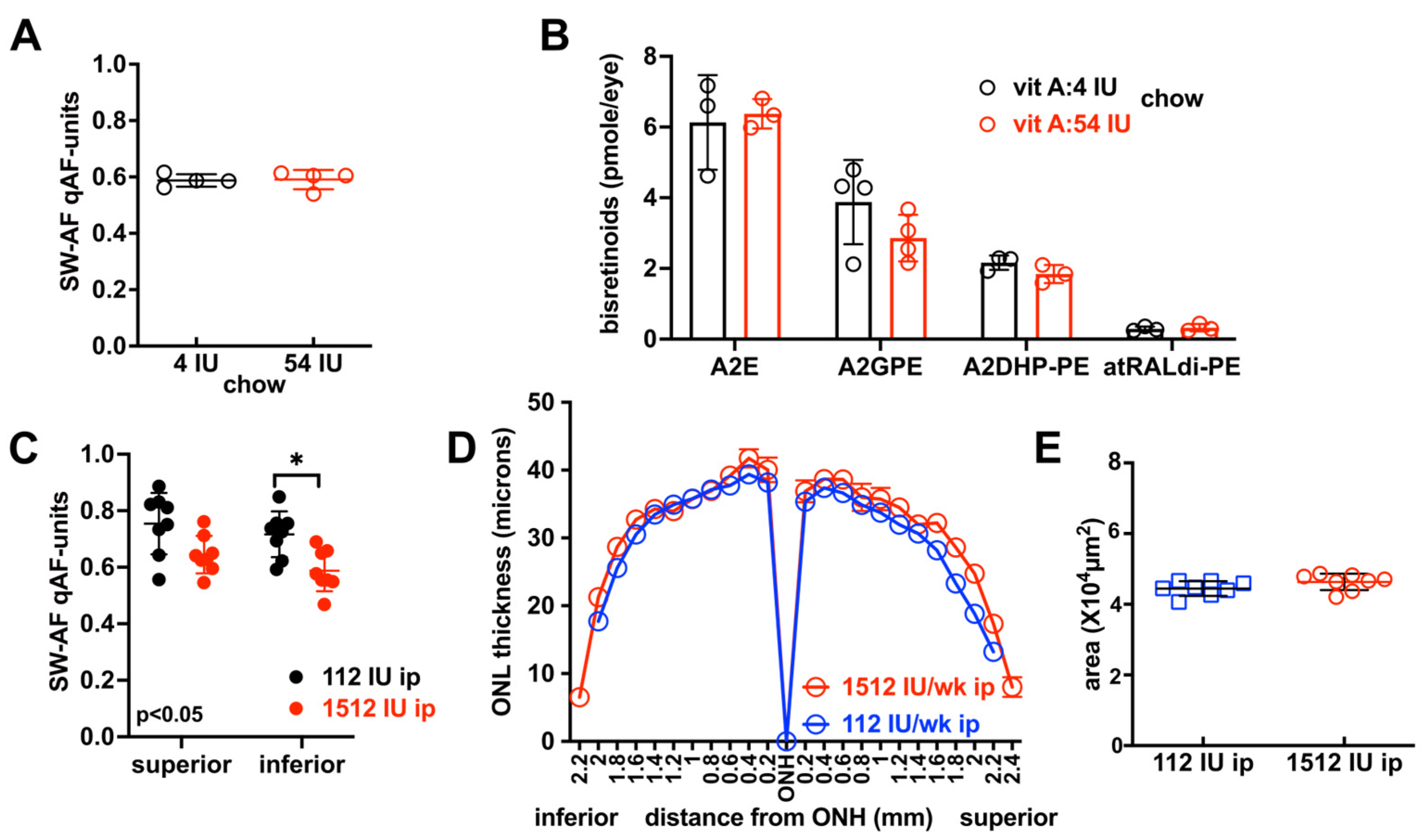

3.5. Effects on SW-AF Intensity and Bisretinoid Levels of Varying Vitamin A Intake with Dark-Rearing Versus Light-Rearing

3.6. Outer Nuclear Layer Thickness in BALB/cJ Mice

3.7. Vitamin A Intake in Cyclic Light-Reared Agouti Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| atRAL | All-trans-retinaldehyde |

| atROL | All-trans-retinol |

| atRE | All-trans-retinyl ester |

| 11-cisRAL | 11-cis-retinaldehyde |

| SW-AF | Short wavelength fundus autofluorescence |

| qAF | Quantitative fundus autofluorescence |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| UPLC | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography |

| RBP4 | Retinol binding protein 4 |

| RP | Retinitis pigmentosa |

| AMD | Age-related macular degeneration |

References

- Blaner, W.S. Vitamin A Signaling and Homeostasis in Obesity, Diabetes, and Metabolic Disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 197, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, R.; Yu, J.; Honda, J.; Hu, J.; Whitelegge, J.; Ping, P.; Wiita, P.; Bok, D.; Sun, H. A Membrane Receptor for Retinol Binding Protein Mediates Cellular Uptake of Vitamin A. Science 2007, 315, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaner, W.S. Retinol-Binding Protein: The Serum Transport Protein for Vitamin A. Endocr. Rev. 1989, 10, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadro, L.; Blaner, W.S.; Salchow, D.J.; Vogel, S.; Piantedosi, R.; Gouras, P.; Freeman, S.; Cosma, M.P.; Colantuoni, V.; Gottesman, M.E. Impaired Retinal Function and Vitamin A Availability in Mice Lacking Retinol-Binding Protein. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 4633–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, D.; Zhao, J.; Kim, H.J.; Shmarakov, I.O.; Blaner, W.S.; Sparrow, J.R. Products of the Visual Cycle Are Detected in Mice Lacking Retinol Binding Protein 4, the Only Known Vitamin A Carrier in Plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeliger, M.W.; Biesalski, H.K.; Wissinger, B.; Gollnick, H.; Gielen, S.; Frank, J.; Beck, S.; Zrenner, E. Phenotype in Retinol Deficiency Due to a Hereditary Defect in Retinol Binding Protein Synthesis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999, 40, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.M.; Rava, P.; Walsh, M.; Rana, M.; Iqbal, J. Multiple Functions of Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubaugh, C.R.; Dhingra, A.; Prakash, B.; Montenegro, D.; Sparrow, J.R.; Daniele, L.L.; Curcio, C.A.; Bell, B.A.; Hussain, M.M.; Boesze-Battaglia, K. Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein Is Necessary to Maintain Lipid Homeostasis and Retinal Function. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2024, 38, e23522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliesler, S.J.; Anderson, R.E. Chemistry and Metabolism of Lipids in the Vertebrate Retina. Prog. Lipid Res. 1983, 22, 79–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldred, G.E.; Katz, M.L. Fluorophores of the Human Retinal Pigment Epithelium: Separation and Spectral Characterization. Exp. Eye Res. 1988, 47, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.L.; Drea, C.M.; Eldred, G.E.; Hess, H.H.; Robison, W.G.J. Influence of Early Photoreceptor Degeneration on Lipofuscin in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Exp. Eye Res. 1986, 43, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.W.; Bok, D. Participation of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium in the Rod Outer Segment Renewal Process. J. Cell Biol. 1969, 42, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, J.R.; Kim, H.J. Bisretinoid Lipofuscin, Fundus Autofluorescence and Retinal Disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2025, 108, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Fishkin, N.; Kong, J.; Nakanishi, K.; Allikmets, R.; Sparrow, J.R. Rpe65 Leu450Met Variant Is Associated with Reduced Levels of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium Lipofuscin Fluorophores A2E and Iso-A2E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 11668–11672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiti, P.; Kong, J.; Kim, S.R.; Sparrow, J.R.; Allikmets, R.; Rando, R.R. Small Molecule RPE65 Antagonists Limit the Visual Cycle and Prevent Lipofuscin Formation. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.K.; Lima de Carvalho, J.R.; Ryu, J.; Tsang, S.H.; Sparrow, J.R. Short-Wavelength and Near-Infrared Autofluorescence in Patients with Deficiencies of the Visual Cycle and Phototransduction. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima de Carvalho, J.R.; Kim, H.J.; Ueda, K.; Zhao, J.; Owji, A.P.; Yang, T.; Tsang, S.H.; Sparrow, J.R. Effects of Deficiency in the RLBP1-Encoded Visual Cycle Protein CRALBP on Visual Dysfunction in Humans and Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 6767–6780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radu, R.A.; Han, Y.; Bui, T.V.; Nusinowitz, S.; Bok, D.; Lichter, J.; Widder, K.; Travis, G.H.; Mata, N.L. Reductions in Serum Vitamin A Arrest Accumulation of Toxic Retinal Fluorophores: A Potential Therapy for Treatment of Lipofuscin-Based Retinal Diseases. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 4393–4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golczak, M.; Kuksa, V.; Maeda, T.; Moise, A.R.; Palczewski, K. Positively Charged Retinoids Are Potent and Selective Inhibitors of the Trans-Cis Isomerization in the Retinoid (Visual) Cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8162–8167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiser, P.D.; Zhang, J.; Badiee, M.; Li, Q.; Shi, W.; Sui, X.; Golczak, M.; Tochtrop, G.P.; Palczewski, K. Catalytic Mechanism of a Retinoid Isomerase Essential for Vertebrate Vision. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Mata, N.L.; Azarian, S.M.; Tzekov, R.T.; Birch, D.G.; Travis, G.H. Insights into the Function of Rim Protein in Photoreceptors and Etiology of Stargardt’s Disease from the Phenotype in Abcr Knockout Mice. Cell 1999, 98, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cideciyan, A.V.; Swider, M.; Aleman, T.S.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Schwartz, S.B.; Windsor, E.A.M.; Roman, A.J.; Sumaroka, A.; Steinberg, J.D.; Jacobson, S.G.; et al. ABCA4 Disease Progression and a Proposed Strategy for Gene Therapy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travis, G.H.; Golczak, M.; Moise, A.R.; Palczewski, K. Diseases Caused by Defects in the Visual Cycle: Retinoids as Potential Therapeutic Agents. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 469–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, A.; Maeda, T.; Imanishi, Y.; Sun, W.; Jastrzebska, B.; Hatala, D.A.; Winkens, H.J.; Hofmann, K.P.; Janssen, J.J.; Baehr, W.; et al. Retinol Dehydrogenase (RDH12) Protects Photoreceptors from Light-Induced Degeneration in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 37697–37704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, A.; Maeda, T.; Imanishi, Y.; Kuksa, V.; Alekseev, A.; Bronson, J.D.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, L.; Sun, W.; Saperstein, D.A.; et al. Role of Photoreceptor-Specific Retinol Dehydrogenase in the Retinoid Cycle in Vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 18822–18832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrispell, J.D.; Feathers, K.L.; Kane, M.A.; Kim, C.Y.; Brooks, M.; Khanna, R.; Kurth, I.; Hubner, C.A.; Gal, A.; Mears, A.J.; et al. Rdh12 Activity and Effects on Retinoid Processing in the Murine Retina. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 21468–21477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, R.; Cho, A.; Xu, C.L.; Tanaka, A.J.; Sparrow, J.R.; Tsang, S.H. Quasidominance in Autosomal Recessive RDH12-Leber Congenital Amaurosis. Ophthalmic Genet. 2020, 41, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.D.; Yamamoto, K.; Ueda, K.; Zhou, J.; Sparrow, J.R. A Novel Source of Methylglyoxal and Glyoxal in Retina: Implications for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C. Diet in Vitamin A Research. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton 2010, 652, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gi, M.; Shim, D.B.; Wu, L.; Bok, J.; Song, M.H.; Choi, J.Y. Progressive Hearing Loss in Vitamin A-Deficient Mice Which May Be Protected by the Activation of Cochlear Melanocyte. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionikaite, V.; Gustafsson, K.L.; Westerlund, A.; Windahl, S.H.; Koskela, A.; Tuukkanen, J.; Johansson, H.; Ohlsson, C.; Conaway, H.H.; Henning, P.; et al. Clinically Relevant Doses of Vitamin A Decrease Cortical Bone Mass in Mice. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 239, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Kim, H.J.; Cheng, C.H.; Jenny, L.A.; De Carvalho Junior, J.R.L.; Chang, Y.J.; Kong, Y.; Hsu, C.W.; Huang, I.W.; Ragi, S.D.; et al. Long-Term Vitamin a Supplementation in a Preclinical Mouse Model for RhoD190N-Associated Retinitis Pigmentosa. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2022, 31, 2438–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delori, F.C.; Dorey, C.K.; Staurenghi, G.; Arend, O.; Goger, D.G.; Weiter, J.J. In Vivo Fluorescence of the Ocular Fundus Exhibits Retinal Pigment Epithelium Lipofuscin Characteristics. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1995, 36, 718–729. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.E.; Maude, M.B. Phospholipids of Bovine Outer Segments. Biochemistry 1970, 9, 3624–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Zhao, J.; Sparrow, J.R. Vitamin A Aldehyde-Taurine Adduct and the Visual Cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24867–24875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, J.S.; Williams, T.P. Photostasis: Regulation of Daily Photon-Catch by Rat Retinas in Response to Various Cyclic Illuminances. Exp. Eye Res. 1986, 43, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskowitz, D.M.; LaVail, M.M.; Duncan, J.L. Light and Inherited Retinal Degeneration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckenlively, J.R.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Daiger, S.P. Autosomal Dominant Sectoral Retinitis Pigmentosa. Two Families with Transversion Mutation in Codon 23 of Rhodopsin. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1960, 1991, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakami, S.; Kolesnikov, A.V.; Kefalov, V.J.; Palczewski, K. P23H Opsin Knock-in Mice Reveal a Novel Step in Retinal Rod Disc Morphogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 1723–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naash, M.L.; Peachey, N.S.; Li, Z.Y.; Gryczan, C.C.; Goto, Y.; Blanks, J.; Milam, A.H.; Ripps, H. Light-Induced Acceleration of Photoreceptor Degeneration in Transgenic Mice Expressing Mutant Rhodopsin. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1996, 37, 775–782. [Google Scholar]

- Lima de Carvalho, J.R.; Tsang, S.H.; Sparrow, J.R. Vitamin A Deficiency Monitored by Quantitative Short Wavelenght Fundus Autofluorescence in a Case of Bariatric Surgery. Retin. Cases Brief. Rep. 2022, 16, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berson, E.L. Light Deprivation for Early Retinitis Pigmentosa. A Hypothesis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1960, 1971, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.A.; Fritz, J.J.; Hauswirth, W.W.; Kaushal, S.; Lewin, A.S. Increased Sensitivity to Light-Induced Damage in a Mouse Model of Autosomal Dominant Retinal Disease. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 1942–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budzynski, E.; Gross, A.K.; McAlear, S.D.; Peachey, N.S.; Shukla, M.; He, F.; Edwards, M.; Won, J.; Hicks, W.L.; Wensel, T.G.; et al. Mutations of the Opsin Gene (Y102H and I307N) Lead to Light-Induced Degeneration of Photoreceptors and Constitutive Activation of Phototransduction in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 14521–14533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, D.K.; Coulibaly, S.F.; Darrow, R.M.; Organisciak, D.T. A Morphometric Study of Light-Induced Damage in Transgenic Rat Models of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwabe, S.; Ying, G.-S.; Aguirre, G.D.; Beltran, W.A. Assessment of Visual Function and Retinal Structure Following Acute Light Exposure in the Light Sensitive T4R Rhodopsin Mutant Dog. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 146, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, M.; Schneider, S.; Kleinlogel, S. Variable Phenotypic Expressivity in Inbred Retinal Degeneration Mouse Lines: A Comparative Study of C3H/HeOu and FVB/N Rd1 Mice. Mol. Vis. 2015, 21, 811–827. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar, S.; Jastrzebska, B.; Montenegro, D.; Sparrow, J.R.; von Lintig, J. Unraveling the Mystery of Ocular Retinoid Turnover: Insights from Albino Mice and the Role of STRA6. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 105781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cai, B.; Jang, Y.P.; Pachydaki, S.; Schmidt, A.M.; Sparrow, J.R. Mechanisms for the Induction of HNE- MDA- and AGE-Adducts, RAGE and VEGF in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2005, 80, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabb, J.W.; Miyagi, M.; Gu, X.; Shadrach, K.; West, K.A.; Sakaguchi, H.; Kamei, M.; Hasan, A.; Yan, L.; Rayborn, M.E.; et al. Drusen Proteome Analysis: An Approach to the Etiology of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14682–14687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, J.T.; Verzijl, N.; Matsunaga, H.; Aotaki-Keen, A.; Lutty, G.A.; te Koppele, J.M.; Miyata, T.; Hjelmeland, L.M. Increase in the Advanced Glycation End Product Pentosidine in Bruch’s Membrane with Age. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999, 40, 775–779. [Google Scholar]

- Pfau, K.; Jeffrey, B.G.; Cukras, C.A. Low-Dose Supplementation with Retinol Improves Retinal Function in Eyes with Age-Related Macular Degeneration but without Reticular Pseudodruses. Retina 2023, 43, 1462–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berson, E.L.; Weigel-DiFranco, C.; Rosner, B.; Gaudio, A.R.; Sandberg, M.A. Association of Vitamin A Supplementation With Disease Course in Children With Retinitis Pigmentosa. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comander, J.; Weigel DiFranco, C.; Sanderson, K.; Place, E.; Maher, M.; Zampaglione, E.; Zhao, Y.; Huckfeldt, R.M.; Bujakowska, K.M.; Pierce, E. Natural History of Retinitis Pigmentosa Based on Genotype, Vitamin A/E Supplementation, and an Electroretinogram Biomarker. JCI Insight 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Rountree, A.; Cleghorn, W.M.; Contreras, L.; Lindsay, K.J.; Sadilek, M.; Gu, H.; Djukovic, D.; Raftery, D.; Satrústegui, J.; et al. Phototransduction Influences Metabolic Flux and Nucleotide Metabolism in Mouse Retina. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 4698–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Montenegro, D.; Zhao, J.; Kim, H.; Cheng, S.; Sparrow, J.R. Tracking Systemic and Ocular Vitamin A. Cells 2026, 15, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020163

Montenegro D, Zhao J, Kim H, Cheng S, Sparrow JR. Tracking Systemic and Ocular Vitamin A. Cells. 2026; 15(2):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020163

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontenegro, Diego, Jin Zhao, Hyejin Kim, Sihua Cheng, and Janet R. Sparrow. 2026. "Tracking Systemic and Ocular Vitamin A" Cells 15, no. 2: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020163

APA StyleMontenegro, D., Zhao, J., Kim, H., Cheng, S., & Sparrow, J. R. (2026). Tracking Systemic and Ocular Vitamin A. Cells, 15(2), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020163