Aberrant Cell Cycle Gene Expression in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

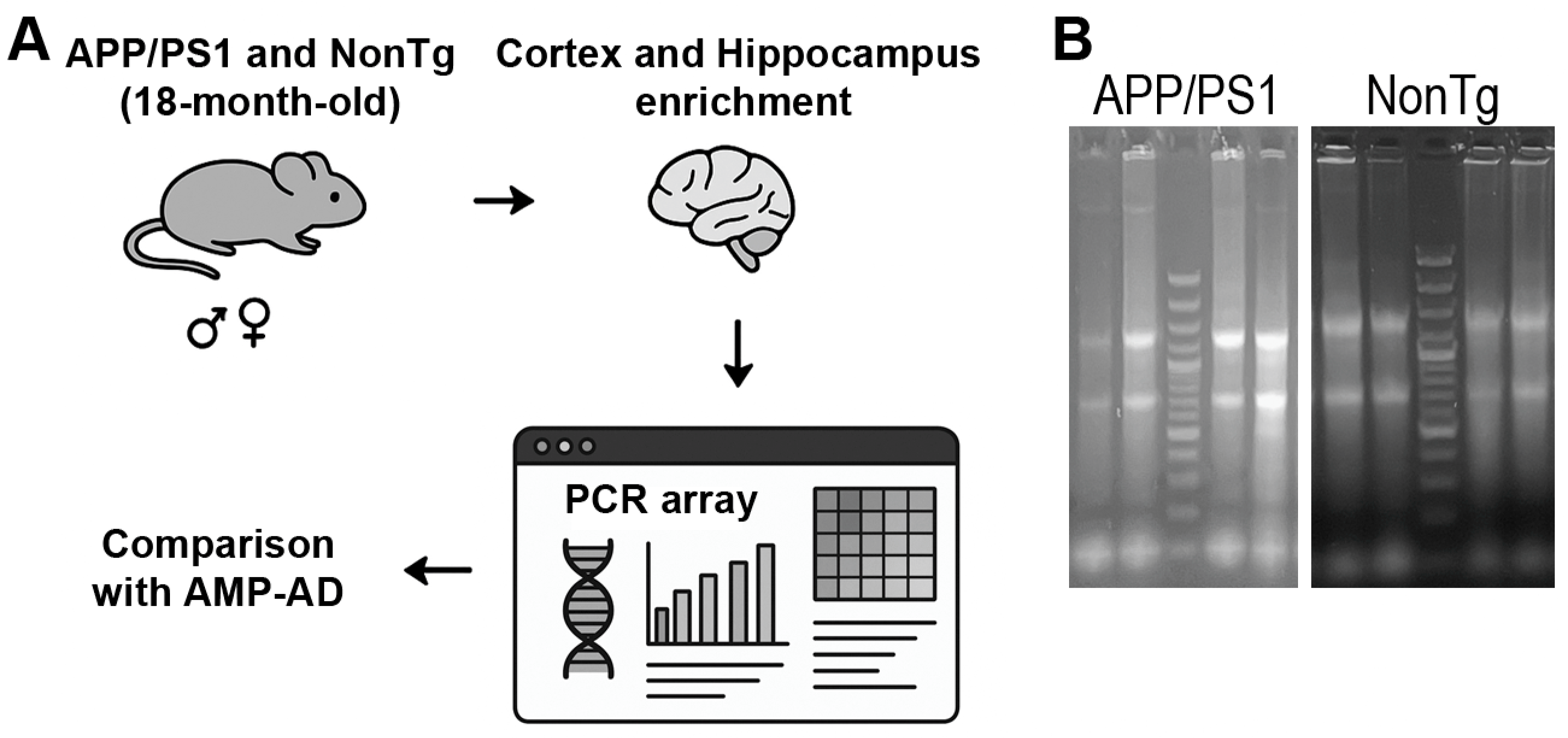

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

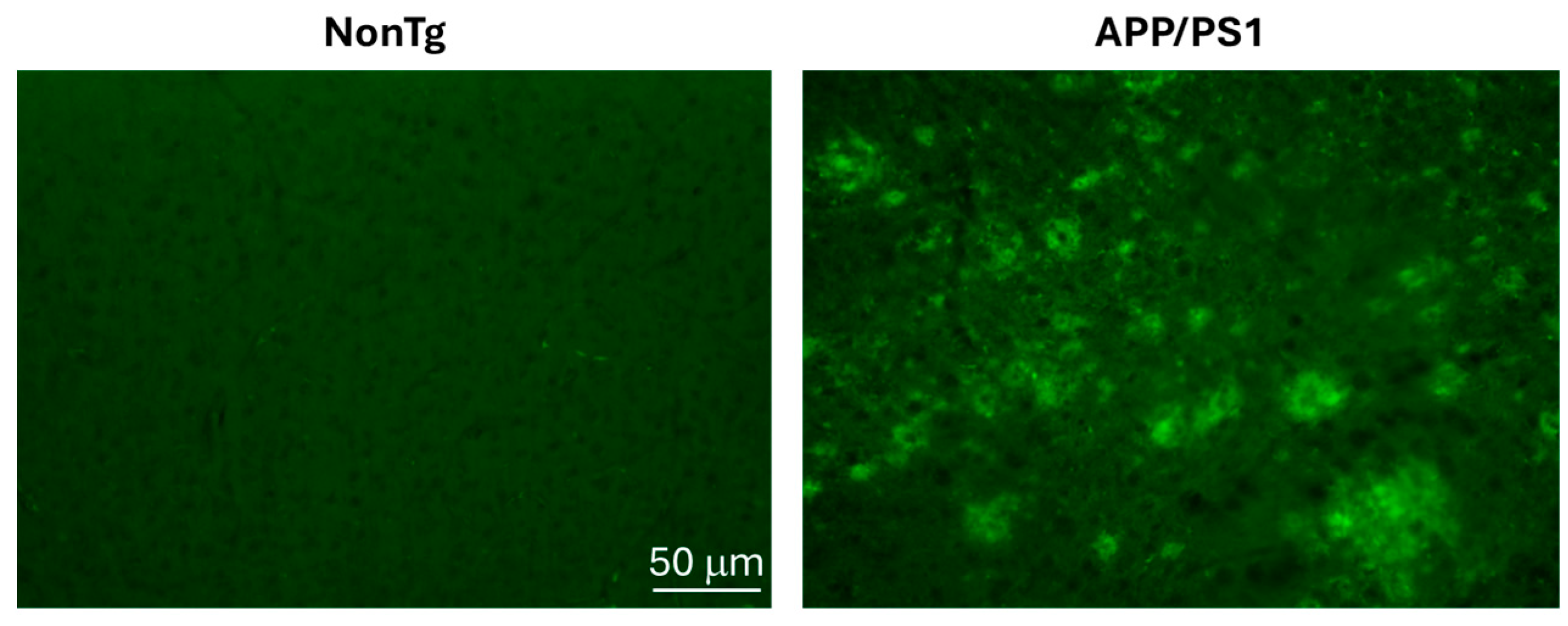

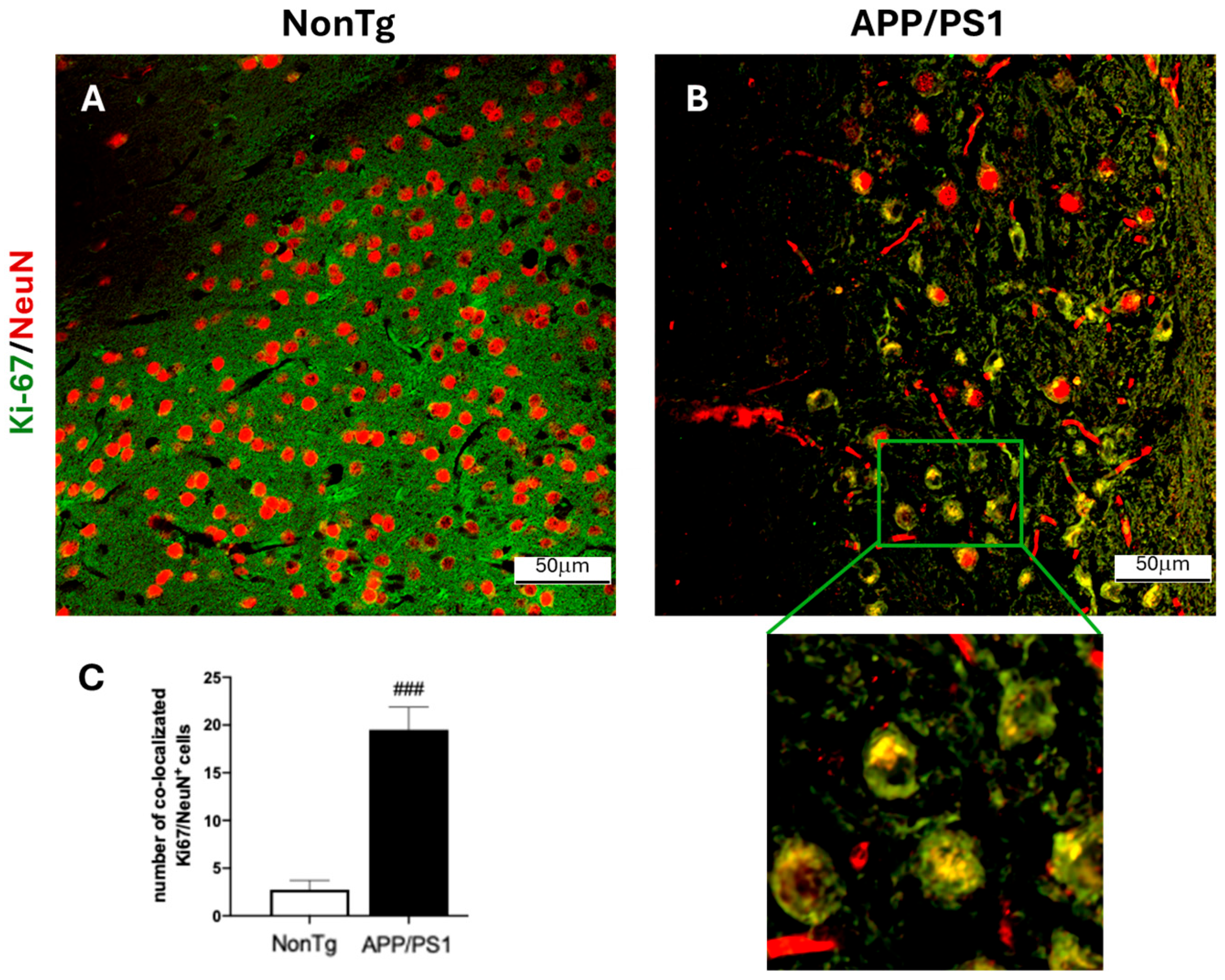

2.2. Immunofluorescence Analysis

2.3. Total RNA Extraction

2.4. cDNA Synthesis

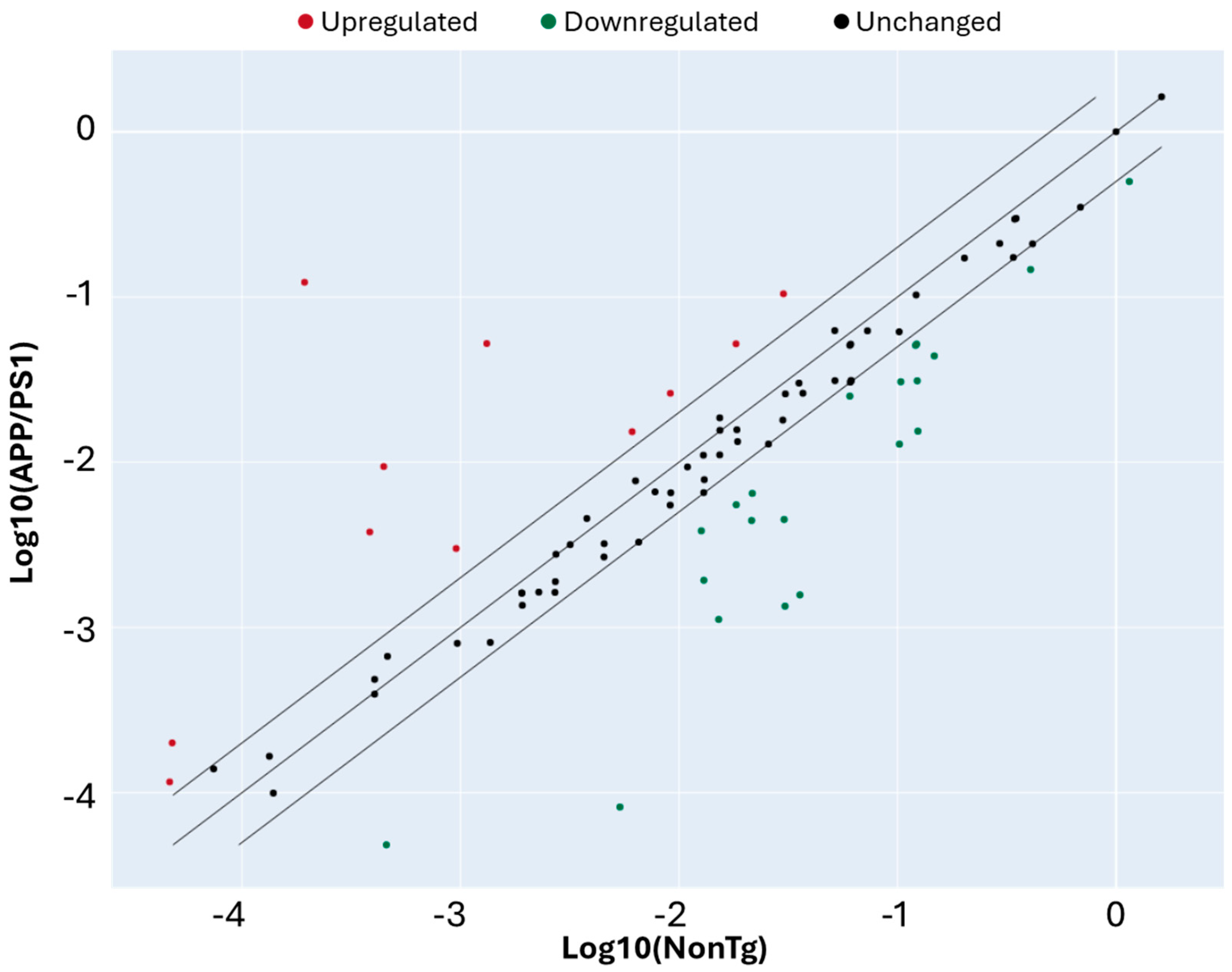

2.5. Real-Time PCR for RT2 Profiler PCR Array

2.6. Western Blot

2.7. AMP-AD Knowledge Portal and Data Analysis

2.8. Data Analysis and Statistics

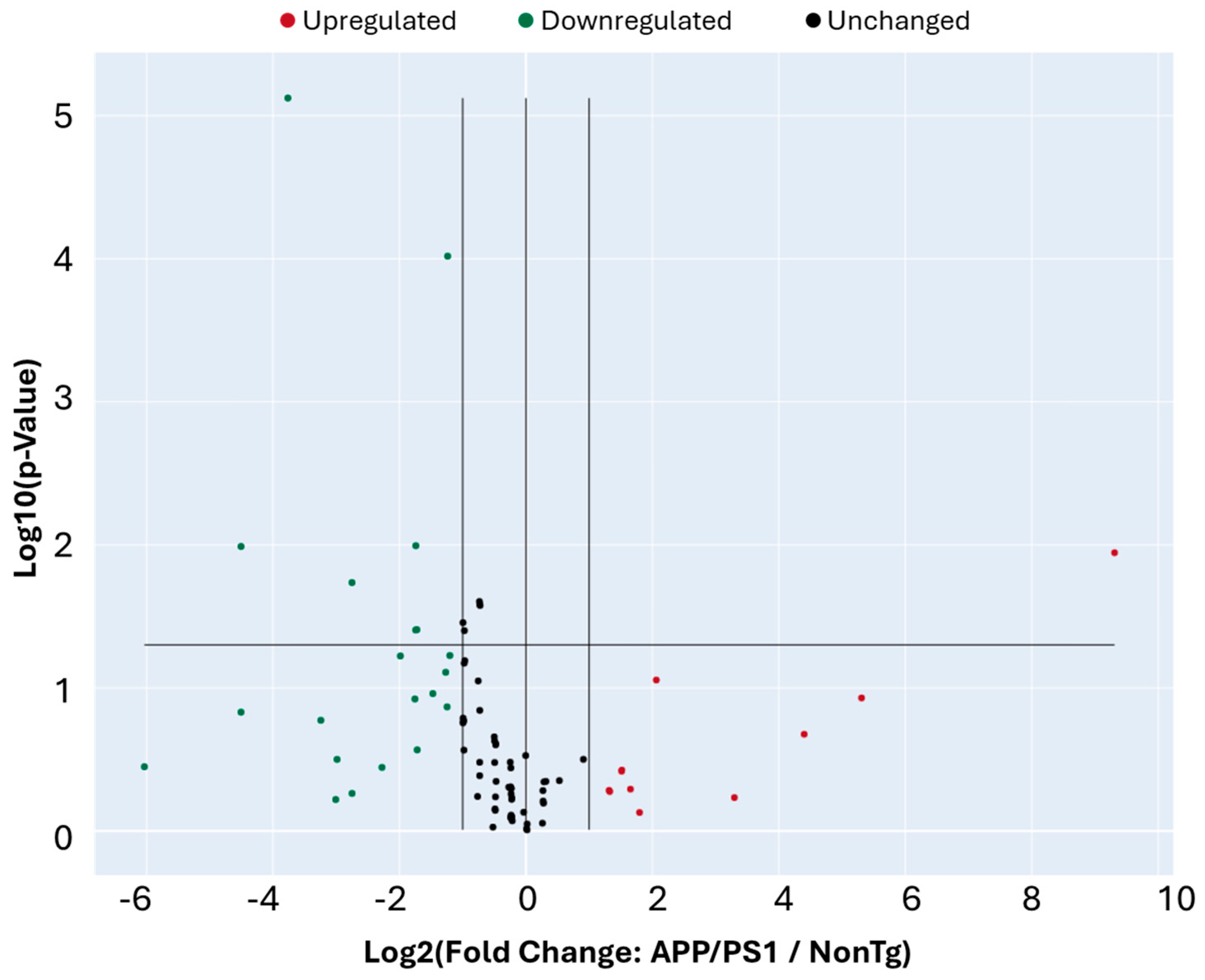

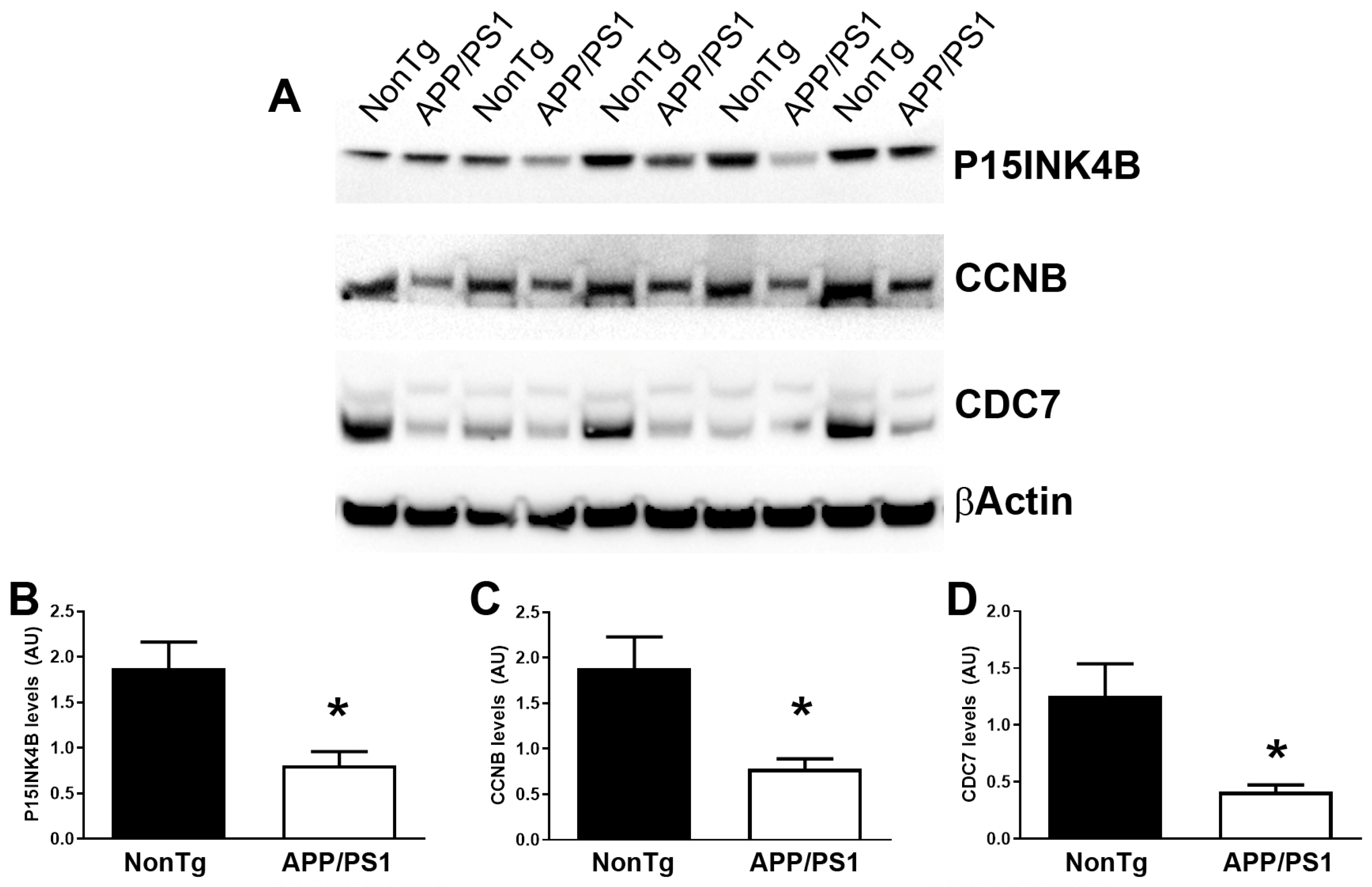

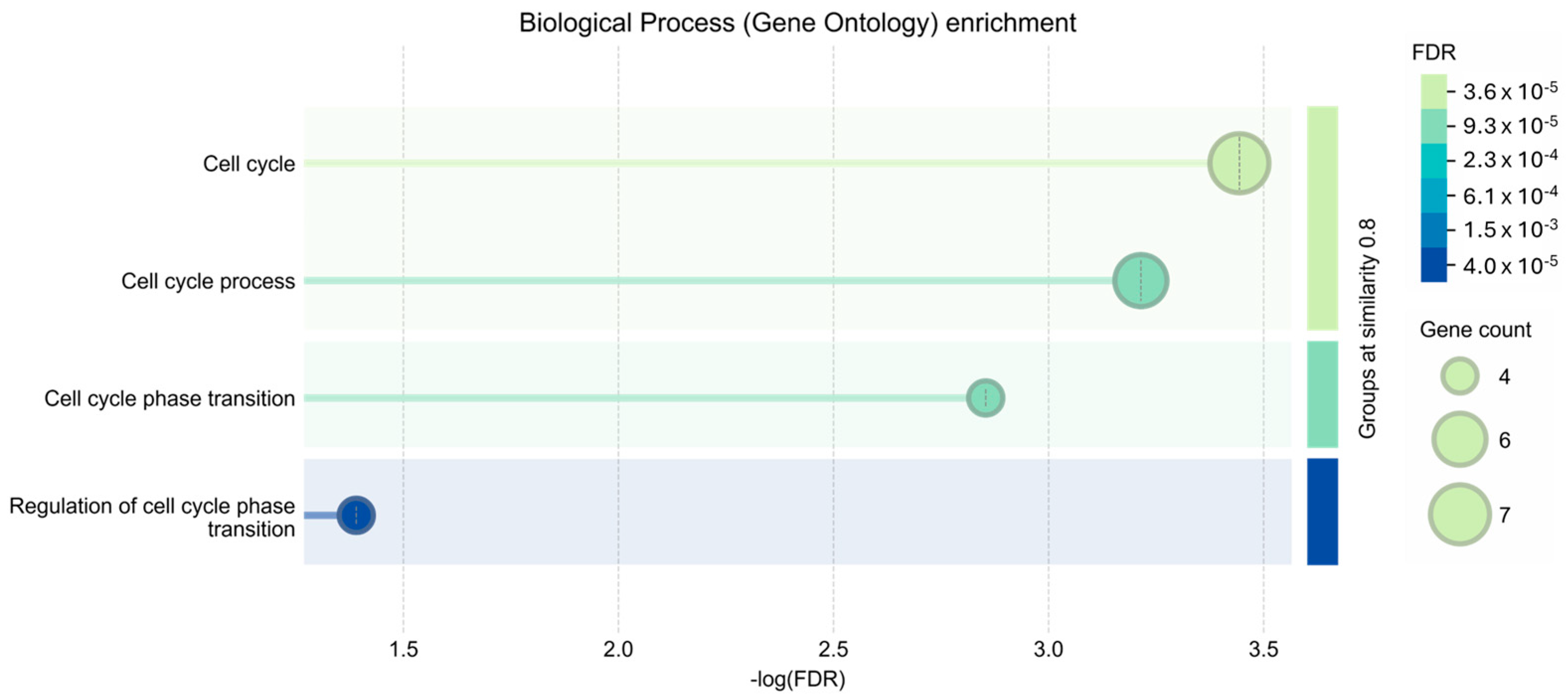

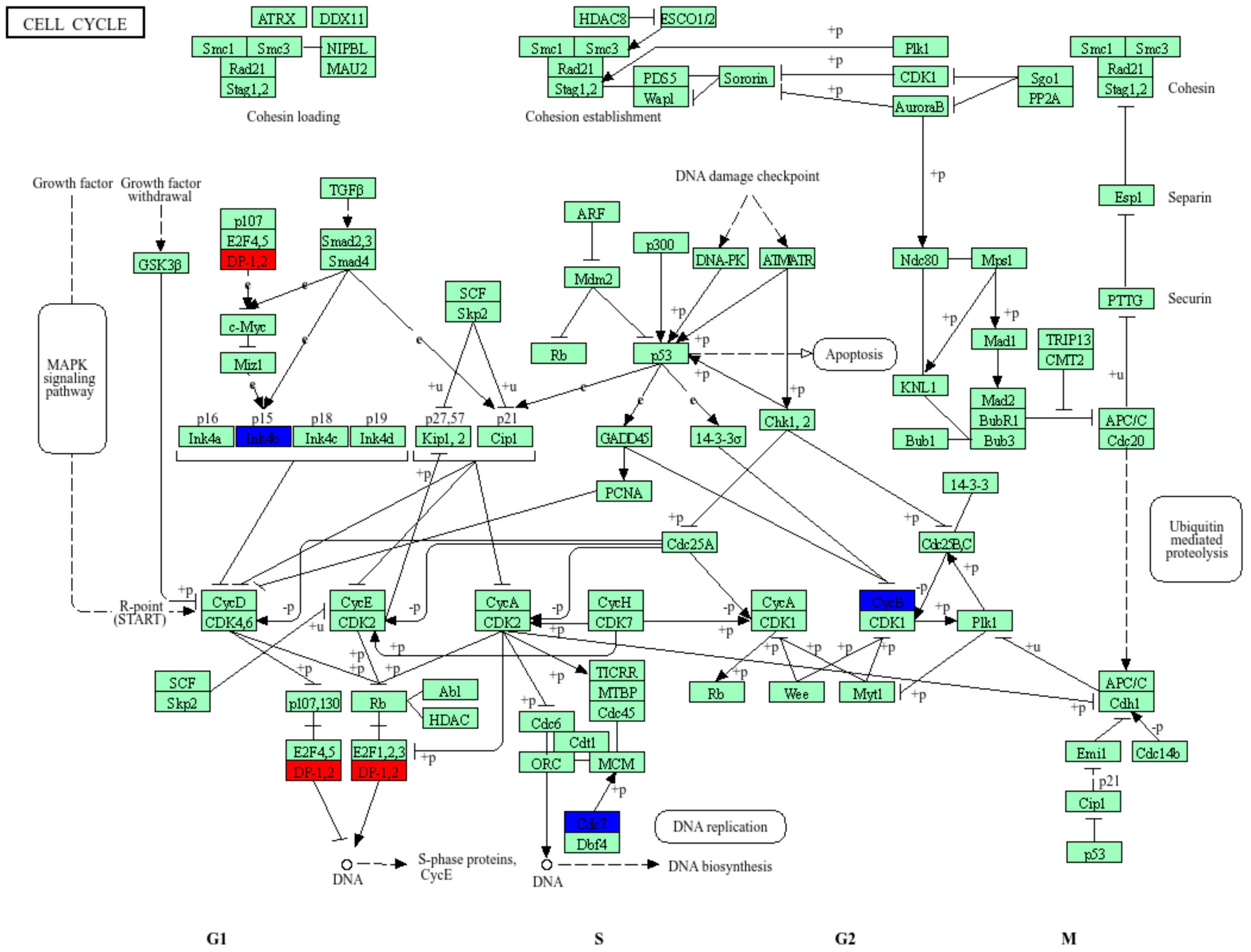

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| PS1 | Presenilin 1 |

| PS2 | Presenilin 2 |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| CCR | Cell cycle re-entry |

| ACTB | β-actin |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| B2M | β-2-microglobulin |

| GUSB | β-glucuronidase |

| HSP90AB1 | heat shock protein HSP 90-β |

| NonTg | non-transgenic |

| AMP-AD | Accelerating Medicines Partnership–Alzheimer’s Disease |

References

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, T. Cell cycle activation and aneuploid neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 46, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, Z.; Esiri, M.M.; Cato, A.M.; Smith, A.D. Cell cycle markers in the hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1997, 94, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShea, A.; Harris, P.L.; Webster, K.R.; Wahl, A.F.; Smith, M.A. Abnormal expression of the cell cycle regulators P16 and CDK4 in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1997, 150, 1933–1939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vincent, I.; Rosado, M.; Davies, P. Mitotic mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease? J. Cell Biol. 1996, 132, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Geldmacher, D.S.; Herrup, K. DNA replication precedes neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 2661–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busser, J.; Geldmacher, D.S.; Herrup, K. Ectopic cell cycle proteins predict the sites of neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 2801–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrup, K.; Neve, R.; Ackerman, S.L.; Copani, A. Divide and die: Cell cycle events as triggers of nerve cell death. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 9232–9239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, T.; Bruckner, M.K.; Mosch, B.; Losche, A. Selective cell death of hyperploid neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosch, B.; Morawski, M.; Mittag, A.; Lenz, D.; Tarnok, A.; Arendt, T. Aneuploidy and DNA replication in the normal human brain and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 6859–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copani, A.; Uberti, D.; Sortino, M.A.; Bruno, V.; Nicoletti, F.; Memo, M. Activation of cell-cycle-associated proteins in neuronal death: A mandatory or dispensable path? Trends Neurosci. 2001, 24, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Raina, A.K.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Alzheimer’s disease: The two-hit hypothesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrup, K.; Yang, Y. Cell cycle regulation in the postmitotic neuron: Oxymoron or new biology? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonda, D.J.; Lee, H.P.; Kudo, W.; Zhu, X.; Smith, M.A.; Lee, H.G. Pathological implications of cell cycle re-entry in Alzheimer disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2010, 12, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrup, K. The contributions of unscheduled neuronal cell cycle events to the death of neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2012, 4, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blalock, E.M.; Geddes, J.W.; Chen, K.C.; Porter, N.M.; Markesbery, W.R.; Landfield, P.W. Incipient Alzheimer’s disease: Microarray correlation analyses reveal major transcriptional and tumor suppressor responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2173–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Beckmann, N.D.; Roussos, P.; Wang, E.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Q.; Ming, C.; Neff, R.; Ma, W.; Fullard, J.F.; et al. The Mount Sinai cohort of large-scale genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic data in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathys, H.; Davila-Velderrain, J.; Peng, Z.; Gao, F.; Mohammadi, S.; Young, J.Z.; Menon, M.; He, L.; Abdurrob, F.; Jiang, X.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2019, 570, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, N.; McCabe, C.; Medina, S.; Varshavsky, M.; Kitsberg, D.; Dvir-Szternfeld, R.; Green, G.; Dionne, D.; Nguyen, L.; Marshall, J.L.; et al. Disease-associated astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease and aging. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowsky, J.L.; Fadale, D.J.; Anderson, J.; Xu, G.M.; Gonzales, V.; Jenkins, N.A.; Copeland, N.G.; Lee, M.K.; Younkin, L.H.; Wagner, S.L.; et al. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: Evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varvel, N.H.; Bhaskar, K.; Patil, A.R.; Pimplikar, S.W.; Herrup, K.; Lamb, B.T. Abeta oligomers induce neuronal cell cycle events in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 10786–10793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repici, A.; Capra, A.P.; Hasan, A.; Bulzomi, M.; Campolo, M.; Paterniti, I.; Esposito, E.; Ardizzone, A. Novel Findings on CCR1 Receptor in CNS Disorders: A Pathogenic Marker Useful in Controlling Neuroimmune and Neuroinflammatory Mechanisms in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.; Min, M.; Yang, C.; Tian, C.; Gookin, S.; Carter, D.; Spencer, S.L. Ki67 is a Graded Rather than a Binary Marker of Proliferation versus Quiescence. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 1105–1112.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.P.; Ding, W.Y.; Wang, P. Molecular mechanism of acetylsalicylic acid in improving learning and memory impairment in APP/PS1 transgenic mice by inhibiting the abnormal cell cycle re-entry of neurons. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 1006216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.W.; Wang, Y.; Dhillon, K.K.; Calses, P.; Villegas, E.; Mitchell, P.S.; Tewari, M.; Kemp, C.J.; Taniguchi, T. Systematic screen identifies miRNAs that target RAD51 and RAD51D to enhance chemosensitivity. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013, 11, 1564–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, T.M.; Butin-Israeli, V.; Wiesolek, H.L.; Zhou, M.; Rehring, J.F.; Wiesmuller, L.; Wu, J.D.; Yang, G.Y.; Hanauer, S.B.; Sebag, J.A.; et al. Neutrophils Alter DNA Repair Landscape to Impact Survival and Shape Distinct Therapeutic Phenotypes of Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 225–238.e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redati, D.; Yang, X.; Lei, C.; Liu, L.; Ge, L.; Wang, H. Expression and Prognostic Value of RAD51 in Adenocarcinoma at the Gastroesophageal Junction. Iran. J. Public Health 2022, 51, 2231–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, J.W.; Calses, P.; Kemp, C.J.; Taniguchi, T. MiR-96 downregulates REV1 and RAD51 to promote cellular sensitivity to cisplatin and PARP inhibition. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 4037–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, R.; Wang, Q.; Qi, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Z. MiR-34s negatively regulate homologous recombination through targeting RAD51. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 666, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, C.; Acharya, G.; Saamarthy, K.; Ochola, D.; Mereddy, S.; Pruitt, K.; Manne, U.; Palle, K. Racial differences in RAD51 expression are regulated by miRNA-214-5P and its inhibition synergizes with olaparib in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2023, 25, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Lan, H.; Yang, Q.; Li, C.; Zeng, L. MicroRNA-29b targeting of cell division cycle 7-related protein kinase (CDC7) regulated vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and migration. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Si, J.; Yang, B.; Yu, J. Upregulation of MicroRNA-15a Contributes to Pathogenesis of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) by Modulating the Expression of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2B (CDKN2B). Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; He, A.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Liao, X.; Lv, Z.; Wang, F.; Mei, H. Hsa-miR-429 promotes bladder cancer cell proliferation via inhibiting CDKN2B. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 68721–68729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, H.; Wu, D.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z. miR-335-5p Regulates Cell Cycle and Metastasis in Lung Adenocarcinoma by Targeting CCNB2. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 6255–6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, K.; Zhao, C.; Liu, H.; Meng, Q.; Wang, Z.; Feng, C.; Li, Y. Effect of miR-205 on proliferation and migration of thyroid cancer cells by targeting CCNB2 and the mechanism. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 19, 2568–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, Y.; Mizushima, T.; Wu, X.; Okuzaki, D.; Yokoyama, Y.; Inoue, A.; Hata, T.; Hirose, H.; Qian, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. miR-4711-5p regulates cancer stemness and cell cycle progression via KLF5, MDM2 and TFDP1 in colon cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, J.S.; Lamichhane, S.; Yun, K.J.; Chae, S.C. MicroRNA 452 regulates SHC1 expression in human colorectal cancer and colitis. Genes Genom. 2023, 45, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, S.; Masamune, A.; Miura, S.; Satoh, K.; Shimosegawa, T. MiR-365 induces gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer cells by targeting the adaptor protein SHC1 and pro-apoptotic regulator BAX. Cell Signal 2014, 26, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.J.; Kwak, S.Y.; Yoo, J.O.; Kim, J.S.; Bae, I.H.; Park, M.J.; Cho, M.Y.; Kim, J.; Han, Y.H. Novel miR-5582-5p functions as a tumor suppressor by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in cancer cells through direct targeting of GAB1, SHC1, and CDK2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 1926–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.L.; Xu, H.W.; Lin, Q.Y. miR129-1 regulates protein phosphatase 1D protein expression under hypoxic conditions in non-small cell lung cancer cells harboring a TP53 mutation. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 2239–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanjirband, M.; Rahgozar, S.; Aberuyi, N. miR-16-5p enhances sensitivity to RG7388 through targeting PPM1D expression (WIP1) in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Drug Resist. 2023, 6, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugalde, A.P.; Ramsay, A.J.; de la Rosa, J.; Varela, I.; Marino, G.; Cadinanos, J.; Lu, J.; Freije, J.M.; Lopez-Otin, C. Aging and chronic DNA damage response activate a regulatory pathway involving miR-29 and p53. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 2219–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, M.T.; Shyh-Chang, N.; Khaw, S.L.; Chin, L.; Teh, C.; Tay, J.; O’Day, E.; Korzh, V.; Yang, H.; Lal, A.; et al. Conserved regulation of p53 network dosage by microRNA-125b occurs through evolving miRNA-target gene pairs. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgantas, R.W., 3rd; Streicher, K.; Luo, X.; Greenlees, L.; Zhu, W.; Liu, Z.; Brohawn, P.; Morehouse, C.; Higgs, B.W.; Richman, L.; et al. MicroRNA-206 induces G1 arrest in melanoma by inhibition of CDK4 and Cyclin D. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2014, 27, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cary, G.A.; Wiley, J.C.; Gockley, J.; Keegan, S.; Amirtha Ganesh, S.S.; Heath, L.; Butler, R.R., 3rd; Mangravite, L.M.; Logsdon, B.A.; Longo, F.M.; et al. Genetic and multi-omic risk assessment of Alzheimer’s disease implicates core associated biological domains. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 10, e12461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Croucher, D.R.; Soliman, M.A.; St-Denis, N.; Pasculescu, A.; Taylor, L.; Tate, S.A.; Hardy, W.R.; Colwill, K.; et al. Temporal regulation of EGF signalling networks by the scaffold protein Shc1. Nature 2013, 499, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, T.; Holzer, M.; Gartner, U. Neuronal expression of cycline dependent kinase inhibitors of the INK4 family in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 1998, 105, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, M.D.; Quachthithu, H.; Gaboriau, D.; Santocanale, C. DNA Replication Dynamics and Cellular Responses to ATP Competitive CDC7 Kinase Inhibitors. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, R.; Deguchi, R.; Komori, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Shirasawa, M.; Angelina, A.; Goto, Y.; Tohjo, F.; Nakahashi, K.; et al. The TFDP1 gene coding for DP1, the heterodimeric partner of the transcription factor E2F, is a target of deregulated E2F. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 663, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yuan, X.; Gui, P.; Liu, R.; Durojaye, O.; Hill, D.L.; Fu, C.; Yao, X.; Dou, Z.; Liu, X. Mad2 promotes Cyclin B2 recruitment to the kinetochore for guiding accurate mitotic checkpoint. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e54171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannenga, B.; Lu, X.; Dumble, M.; Van Maanen, M.; Nguyen, T.A.; Sutton, R.; Kumar, T.R.; Donehower, L.A. Augmented cancer resistance and DNA damage response phenotypes in PPM1D null mice. Mol. Carcinog. 2006, 45, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, S.K.; Sullivan, M.R.; Bernstein, K.A. Novel insights into RAD51 activity and regulation during homologous recombination and DNA replication. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 94, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezek, J.; Smethurst, D.G.J.; Stieg, D.C.; Kiss, Z.A.C.; Hanley, S.E.; Ganesan, V.; Chang, K.T.; Cooper, K.F.; Strich, R. Cyclin C: The Story of a Non-Cycling Cyclin. Biology 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, S.S.; De Strooper, B. Alterations of the microRNA network cause neurodegenerative disease. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Gene Symbol | Fold Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription factor Dp-1 | Tfdp1 | 634.56 |

| MutS Homolog 2 | Msh2 | 39.64 |

| Stratifin (14-3-3 sigma) | Sfn | 21.13 |

| Cyclin D3 | Ccnd3 | 9.83 |

| Tumor protein p63 | Trp63 | 4.18 |

| Structural maintenance of chromosomes 1A | Smc1a | 3.47 |

| E2F transcription factor 1 | E2f1 | 3.15 |

| Growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible alpha | Gadd45a | 2.86 |

| Glucuronidase beta | Gusb | 2.86 |

| Heat shock protein 90 alpha family class B member 1 | Hsp90ab1 | 2.51 |

| RAD9 checkpoint clamp component A | Rad9a | 2.49 |

| RAS-related nuclear protein | Ran | −2.30 |

| Protein phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent 1D | Ppm1d | −2.36 |

| Polycystin 1 | Pkd1 | −2.37 |

| ATM serine/threonine kinase | Atm | −2.41 |

| Cyclin D2 | Ccnd2 | −2.77 |

| BCL2 apoptosis regulator | Bcl2 | −3.29 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B | Cdkn2b | −3.30 |

| RAD51 recombinase | Rad51 | −3.34 |

| Cell division cycle 7-related protein kinase | Cdc7 | −3.35 |

| Mitotic arrest deficient-like 1 | Mad2l1 | −3.38 |

| HUS1 checkpoint clamp component | Hus1 | −3.96 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Gapdh | −4.85 |

| Cyclin B2 | Ccnb2 | −6.73 |

| Cyclin E1 | Ccne1 | −6.73 |

| DNA damage inducible transcript 3 (CHOP) | Ddit3 | −7.93 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | Cdk4 | −8.04 |

| Checkpoint kinase 2 | Chek2 | −9.47 |

| SHC adaptor protein 1 | Shc1 | −13.59 |

| Cyclin C | Ccnc | −22.72 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase regulatory subunit 1B | Cks1b | −22.73 |

| Beta-actin | Actb | −65.53 |

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Shc1 | SHC Adaptor Protein 1 | 0.000008 |

| Ppm1d | Protein Phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+-Dependent 1D | 0.000096 |

| Rad51 | RAD51 Recombinase | 0.010135 |

| Ccnc | Cyclin C | 0.010261 |

| Tfdp1 | Transcription Factor Dp-1 | 0.011345 |

| Ccnb2 | Cyclin B2 | 0.018341 |

| Cdkn2b | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2B | 0.039137 |

| Cdc7 | Cell Division Cycle 7 | 0.039379 |

| Genes | miRNAs | References |

|---|---|---|

| RAD51 | miR-103, miR-107, miR-155, miR-182, miR-96, miR-34a/b/c, miR-214-5p | [25,26,27,28,29,30] |

| CDC7 | miR-29b-3p | [31] |

| CDKN2B | miR-15a-5p, miR-429 | [32,33] |

| CCNB2 | miR-335-5p, miR-205 | [34,35] |

| TFDP1 | miR-4711-5p | [36] |

| SHC1 | miR-452, miR-365; miR-5582-5p | [37,38,39] |

| PPM1D (WIP1) | miR-129-1-3p, miR-16-5p, miR-29 family | [40,41,42] |

| CCNC (Cyclin C) | miR-125b; miR-206 | [43,44] |

| CDC7 | PPM1D | CCNC | SHC1 | CDKN2B-AS1 | TFDP1 | RAD51 | CCNB2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RISK SCORE | 3.58 | 2.53 | 2.42 | 1.19 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 1.38 | 0.89 | |

| ACC | L2FC | −0.117 | 0.132 | −0.0922 | −0.106 | −0.0729 | 0.11 | - | - |

| p-VALUE | 0.0433 | 0.000145 | 0.0045 | 0.147 | 0.467 | 0.000279 | - | - | |

| CBE | L2FC | −0.0341 | 0.194 | −0.0913 | 0.000867 | - | 0.0118 | 0.265 | - |

| p-VALUE | 0.656 | 0.00116 | 0.0836 | 0.992 | - | 0.843 | 0.000975 | - | |

| DLPFC | L2FC | −0.0821 | 0.194 | −0.0644 | −0.2 | −0.0346 | 0.0616 | - | - |

| p-VALUE | 0.0661 | 0.00116 | 0.0177 | 0.000217 | 0.721 | 0.0201 | - | - | |

| FP | L2FC | −0.175 | 0.113 | −0.0248 | −0.0164 | 0.073 | 0.00775 | −0.251 | −0.345 |

| p-VALUE | 0.053 | 0.0338 | 0.621 | 0.889 | 0.491 | 0.88 | 0.033 | 0.0104 | |

| IGF | L2FC | −0.248 | 0.131 | −0.0926 | 0.0955 | 0.0793 | 0.00603 | −0.103 | −0.925 |

| p-VALUE | 0.00262 | 0.00709 | 0.0311 | 0.302 | 0.476 | 0.904 | 0.451 | 0.545 | |

| PCC | L2FC | −0.121 | 0.172 | −0.0854 | −0.121 | −0.1 | 0.0597 | - | - |

| p-VALUE | 0.0279 | 0.0000051 | 0.0119 | 0.105 | 0.314 | 0.0777 | - | - | |

| PHG | L2FC | −0.354 | 0.285 | −0.0806 | 0.17 | 0.325 | −0.0923 | 0.196 | 0.148 |

| p-VALUE | 0.00000159 | 6.35 × 10−11 | 0.0335 | 0.0297 | 0.0000537 | 0.00708 | 0.0639 | 0.216 | |

| STG | L2FC | −0.27 | 0.138 | −0.122 | 0.13 | 0.06 | −0.0527 | −0.0922 | −0.1 |

| p-VALUE | 0.00111 | 0.00512 | 0.00443 | 0.157 | 0.603 | 0.211 | 0.511 | 0.513 | |

| TCX | L2FC | −0.236 | 0.342 | −0.15 | 0.299 | - | 0.0801 | 0.097 | - |

| p-VALUE | 0.00153 | 6.69 × 10−7 | 0.00387 | 0.0000149 | - | 0.0865 | 0.343 | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lanza, M.; Scuruchi, M.; Saitta, A.; Basilotta, R.; Aliquò, F.; Casili, G.; Esposito, E.; Copani, A.; Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A. Aberrant Cell Cycle Gene Expression in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2026, 15, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020132

Lanza M, Scuruchi M, Saitta A, Basilotta R, Aliquò F, Casili G, Esposito E, Copani A, Oddo S, Caccamo A. Aberrant Cell Cycle Gene Expression in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells. 2026; 15(2):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020132

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanza, Marika, Michele Scuruchi, Alessandra Saitta, Rossella Basilotta, Federica Aliquò, Giovanna Casili, Emanuela Esposito, Agata Copani, Salvatore Oddo, and Antonella Caccamo. 2026. "Aberrant Cell Cycle Gene Expression in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease" Cells 15, no. 2: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020132

APA StyleLanza, M., Scuruchi, M., Saitta, A., Basilotta, R., Aliquò, F., Casili, G., Esposito, E., Copani, A., Oddo, S., & Caccamo, A. (2026). Aberrant Cell Cycle Gene Expression in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells, 15(2), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020132