Tranilast Does Not Inhibit TRPV2

Highlights

- Tranilast does not directly block TRPV2 currents or calcium influx induced by established agonists.

- Tranilast reduces oxidation-induced TRPV2 modulation rather than direct channel inhibition.

- The long-held view of tranilast as a TRPV2 blocker should be reconsidered; its effects are indirect and redox-dependent.

- This work refines the pharmacological understanding of TRPV2 modulation and guides more accurate experimental and therapeutic use of tranilast in TRPV2 channel research.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Electrophysiology

2.4. Calcium Imaging

2.5. Phagocytosis Assay

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Declaration of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

3. Results

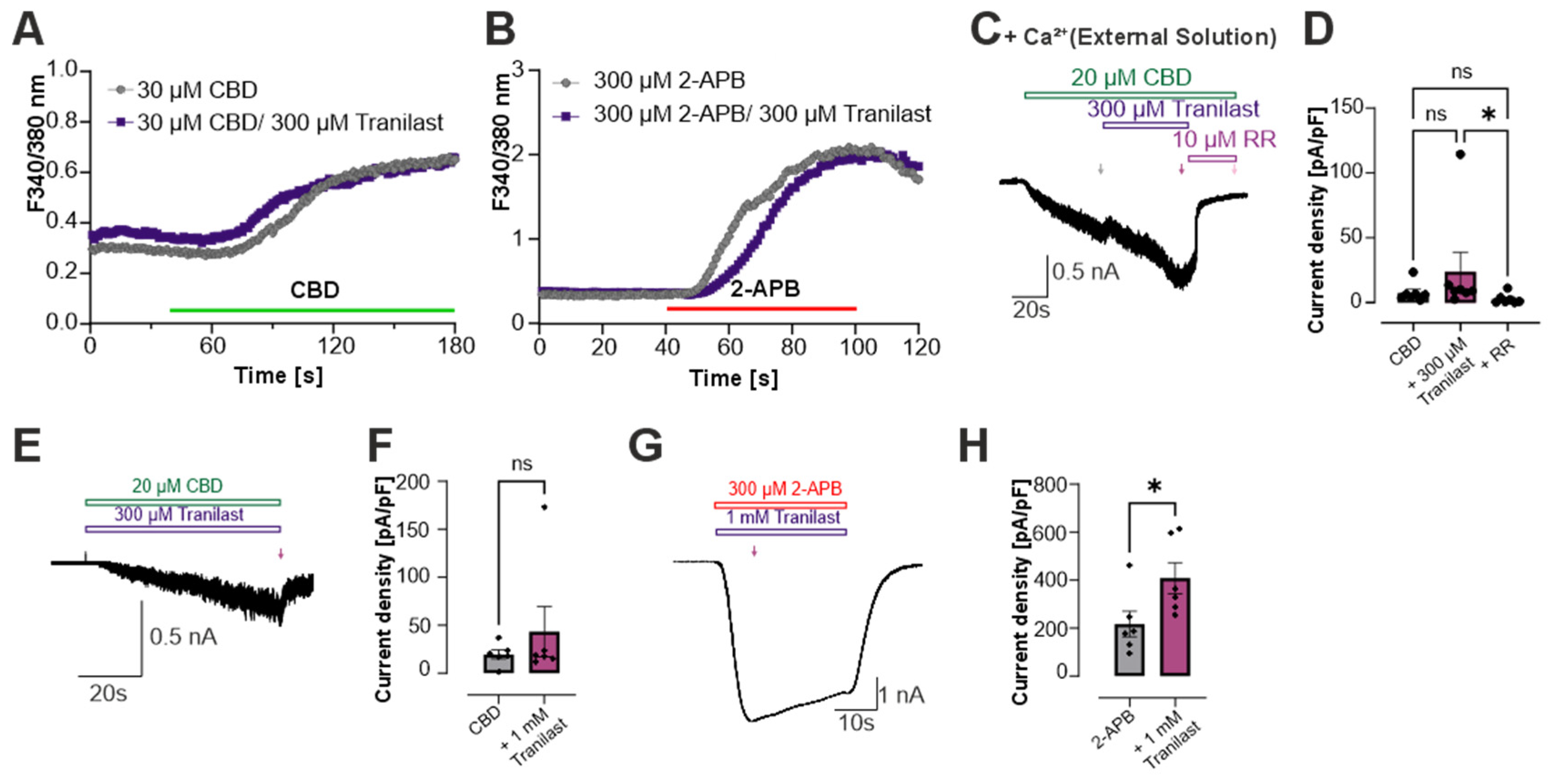

3.1. Tranilast Does Not Inhibit TRPV2-Mediated Currents in HEK 293 Cells

3.2. Tranilast Does Not Inhibit Calcium Influx in Rat TRPV2-Expressing HEK293 Cells

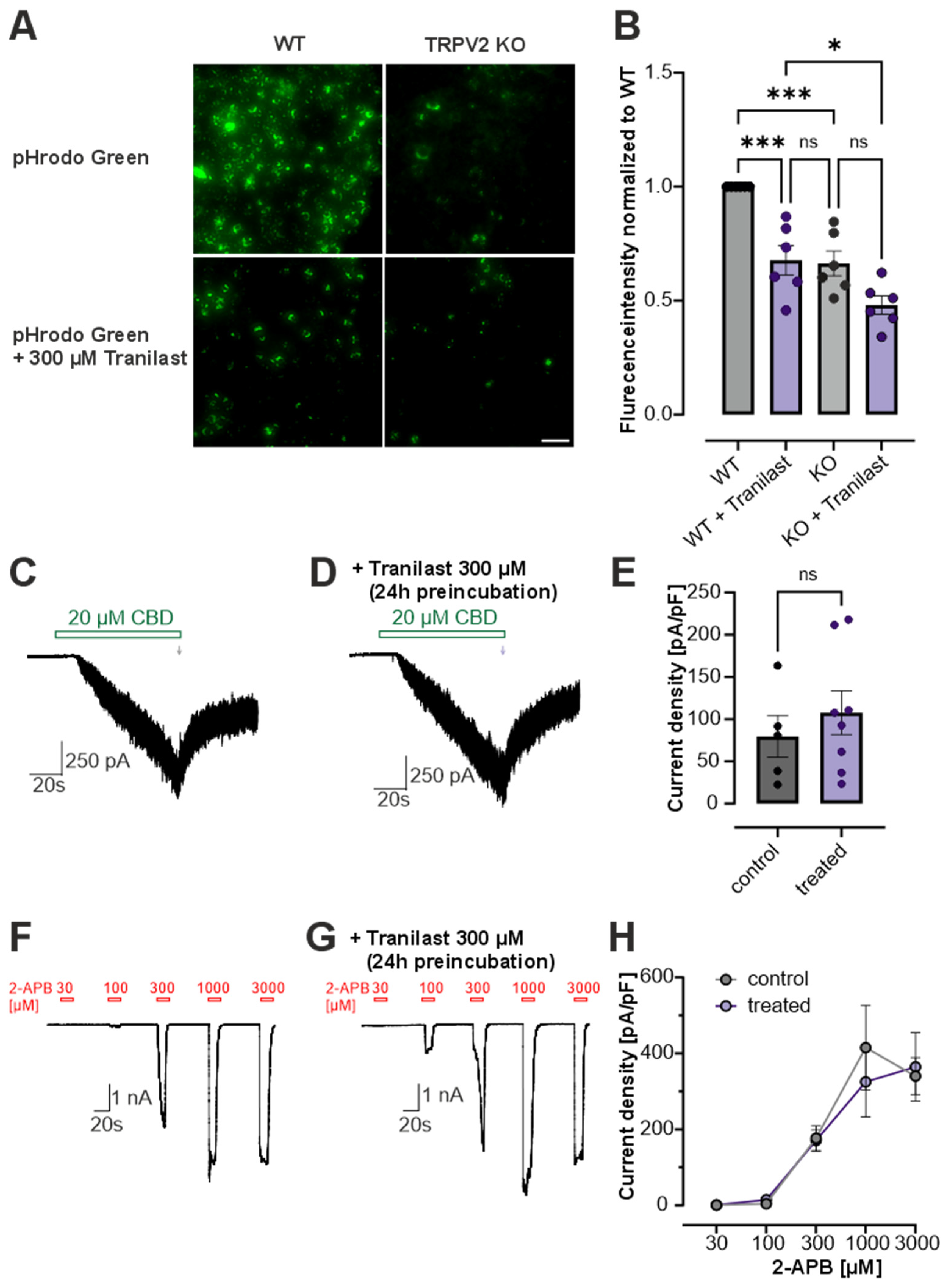

3.3. Tranilast Reduces Phagocytosis in RBL Cells

3.4. Tranilast Reduces Oxidation-Induced Activation of TRPV2, TRPA1 and Voltage-Gated Na+ Channels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-APB | 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borat |

| CADs | cinnamoyl anthranilate derivatives |

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| CHO | Chinese hamster ovary |

| ChT | Chloramin T |

| HEK293 | human embryonic kidney |

| IGF-1 | insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| KO | knockout |

| NASH | non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| PDGF | platelet-derived growth factor |

| PMA | phorbol myristate acetate |

| PGD2 | prostaglandin D2 |

| RBL | rat basophilic leukemia |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RR | Ruthenium Red |

| TRP | Transient receptor potential |

| TRPA1 | Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 |

| TRPV1 | Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 |

| TRPV2 | Transient receptor potential vanilloid 2 |

| WT | wildtype |

References

- Caterina, M.J.; Rosen, T.A.; Tominaga, M.; Brake, A.J.; Julius, D. A capsaicin-receptor homologue with a high threshold for noxious heat. Nature 1999, 398, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, T.M.; Park, U.; Vonakis, B.M.; Raben, D.M.; Soloski, M.J.; Caterina, M.J. TRPV2 has a pivotal role in macrophage particle binding and phagocytosis. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.R.; Johnson, W.M.; Pilat, J.M.; Kiselar, J.; DeFrancesco-Lisowitz, A.; Zigmond, R.E.; Moiseenkova-Bell, V.Y. Nerve Growth Factor Regulates Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 2 via Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Signaling To Enhance Neurite Outgrowth in Developing Neurons. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 35, 4238–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entin-Meer, M.; Keren, G. Potential roles in cardiac physiology and pathology of the cation channel TRPV2 expressed in cardiac cells and cardiac macrophages: A mini-review. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H181–H188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, S.E.; Mann, A.; Jones, S.; Robbins, N.; Alkhattabi, A.; Worley, M.C.; Gao, X.; Lasko-Roiniotis, V.M.; Karani, R.; Fulford, L.; et al. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 2 function regulates cardiac hypertrophy via stretch-induced activation. J. Hypertens. 2017, 35, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, T.; Tojkander, S. TRPV Protein Family-From Mechanosensing to Cancer Invasion. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leverrier-Penna, S.; Destaing, O.; Penna, A. Insights and perspectives on calcium channel functions in the cockpit of cancerous space invaders. Cell Calcium 2020, 90, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralvarez-Marin, A.; Donate-Macian, P.; Gaudet, R. What do we know about the transient receptor potential vanilloid 2 (TRPV2) ion channel? FEBS J. 2013, 280, 5471–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talyzina, I.A.; Nadezhdin, K.D.; Sobolevsky, A.I. Forty sites of TRP channel regulation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2025, 84, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriens, J.; Appendino, G.; Nilius, B. Pharmacology of vanilloid transient receptor potential cation channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 75, 1262–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumroy, R.A.; De Jesus-Perez, J.J.; Protopopova, A.D.; Rocereta, J.A.; Fluck, E.C.; Fricke, T.; Lee, B.H.; Rohacs, T.; Leffler, A.; Moiseenkova-Bell, V. Molecular details of ruthenium red pore block in TRPV channels. EMBO Rep. 2024, 25, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvin, V.; Penna, A.; Chemin, J.; Lin, Y.L.; Rassendren, F.A. Pharmacological characterization and molecular determinants of the activation of transient receptor potential V2 channel orthologs by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007, 72, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde, J.; Pumroy, R.A.; Baker, C.; Rodrigues, T.; Guerreiro, A.; Sousa, B.B.; Marques, M.C.; de Almeida, B.P.; Lee, S.; Leites, E.P.; et al. Allosteric Antagonist Modulation of TRPV2 by Piperlongumine Impairs Glioblastoma Progression. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 868–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluhm, Y.; Raudszus, R.; Wagner, A.; Urban, N.; Schaefer, M.; Hill, K. Valdecoxib blocks rat TRPV2 channels. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 915, 174702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, C.; Held, K.; Ciprietti, M.; De Clercq, K.; Kerselaers, S.; Marchand, A.; Chaltin, P.; Voets, T.; Vriens, J. Loratadine, an antihistaminic drug, suppresses the proliferation of endometrial stromal cells by inhibition of TRPV2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 928, 175086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Oishi, Y.; Doi, I.; Shibata, H.; Kojima, I. Inhibition of proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells by a blocker of Ca(2+)-permeable channel. Cell Calcium 1997, 22, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, Y.; Katayama, Y.; Okuno, Y.; Wakabayashi, S. Novel inhibitor candidates of TRPV2 prevent damage of dystrophic myocytes and ameliorate against dilated cardiomyopathy in a hamster model. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 14042–14057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darakhshan, S.; Pour, A.B. Tranilast: A review of its therapeutic applications. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 91, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Mogami, H.; Kanzaki, M.; Shibata, H.; Kojima, I. Blockade of DNA synthesis induced by platelet-derived growth factor by tranilast, an inhibitor of calcium entry, in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996, 50, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, L.; Kanzaki, M.; Shibata, H.; Kojima, I. Activation of calcium-permeable cation channel by insulin in Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing human insulin receptors. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boels, K.; Glassmeier, G.; Herrmann, D.; Riedel, I.B.; Hampe, W.; Kojima, I.; Schwarz, J.R.; Schaller, H.C. The neuropeptide head activator induces activation and translocation of the growth-factor-regulated Ca(2+)-permeable channel GRC. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 3599–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzaki, M.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Mashima, H.; Li, L.; Shibata, H.; Kojima, I. Translocation of a calcium-permeable cation channel induced by insulin-like growth factor-I. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999, 1, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hisanaga, E.; Nagasawa, M.; Ueki, K.; Kulkarni, R.N.; Mori, M.; Kojima, I. Regulation of calcium-permeable TRPV2 channel by insulin in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 2009, 58, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyagi, K.; Ohara-Imaizumi, M.; Nishiwaki, C.; Nakamichi, Y.; Nagamatsu, S. Insulin/phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway accelerates the glucose-induced first-phase insulin secretion through TrpV2 recruitment in pancreatic beta-cells. Biochem. J. 2010, 432, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, L.; Lin, X.; Huang, D.; Lu, W.; Lv, H.; Tang, F.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Structure-Based Discovery of a Subtype-Selective Inhibitor Targeting a Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Channel. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudszus, R.; Paulig, A.; Urban, N.; Deckers, A.; Grassle, S.; Vanderheiden, S.; Jung, N.; Brase, S.; Schaefer, M.; Hill, K. Pharmacological inhibition of TRPV2 attenuates phagocytosis and lipopolysaccharide-induced migration of primary macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 180, 2736–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveque, M.; Penna, A.; Le Trionnaire, S.; Belleguic, C.; Desrues, B.; Brinchault, G.; Jouneau, S.; Lagadic-Gossmann, D.; Martin-Chouly, C. Phagocytosis depends on TRPV2-mediated calcium influx and requires TRPV2 in lipids rafts: Alteration in macrophages from patients with cystic fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Ye, T.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, F.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, B.; Chen, B.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; et al. TRPV2 Inhibition Prevents Right Ventricular Remodeling and Arrhythmia in Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension. FASEB J. 2025, 39, e70949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Song, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Yu, F.; Chu, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; et al. TRPV2 inhibitor tranilast prevents atrial fibrillation in rat models of pulmonary hypertension. Cell Calcium 2024, 117, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, L.; Kiefmann, M.; Gudermann, T.; Dietrich, A. TRPV2 channels facilitate pulmonary endothelial barrier recovery after ROS-induced permeability. Redox Biol. 2025, 85, 103720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Cheng, C.; Cheruiyot, A.; Yuan, J.; Yang, Y.; Hwang, S.; Foust, D.; Tsao, N.; Wilkerson, E.; Mosammaparast, N.; et al. TCAF1 promotes TRPV2-mediated Ca(2+) release in response to cytosolic DNA to protect stressed replication forks. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, T.; Shakado, S.; Yamauchi, E.; Tokushige, H.; Miyayama, T.; Yamauchi, R.; Fukuda, H.; Fukunaga, A.; Tanaka, T.; Takata, K.; et al. Tranilast Inhibits TRPV2 and Suppresses Fibrosis Progression and Weight Gain in a NASH Model Mouse. Anticancer. Res. 2024, 44, 3593–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapak, P.; Bishnoi, M.; Sharma, S.S. Tranilast, a Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 2 Channel (TRPV2) Inhibitor Attenuates Amyloid beta-Induced Cognitive Impairment: Possible Mechanisms. Neuromolecular Med. 2022, 24, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Suenaga, M.; Mizutani, Y.; Matsui, K.; Yoshida, A.; Nakamoto, T.; Kato, S. Role of transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 2 in lower oesophageal sphincter in rat acid reflux oesophagitis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 146, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Fukudome, T.; Motoyoshi, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Kuru, S.; Segawa, K.; Kitao, R.; Watanabe, C.; Tamura, T.; Takahashi, T.; et al. Efficacy of tranilast in preventing exacerbating cardiac function and death from heart failure in muscular dystrophy patients with advanced-stage heart failure: A single-arm, open-label, multicenter study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Matsui, M.; Iwata, Y.; Asakura, M.; Saito, T.; Fujimura, H.; Sakoda, S. A Pilot Study of Tranilast for Cardiomyopathy of Muscular Dystrophy. Intern. Med. 2018, 57, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, Y.; Matsumura, T. Blockade of TRPV2 is a Novel Therapy for Cardiomyopathy in Muscular Dystrophy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura, T.; Hashimoto, H.; Sekimizu, M.; Saito, A.M.; Iwata, Y.; Asakura, M.; Kimura, K.; Tamura, T.; Funato, M.; Segawa, K.; et al. Study Protocol for a Multicenter, Open-Label, Single-Arm Study of Tranilast for Cardiomyopathy of Muscular Dystrophy. Kurume Med. J. 2021, 66, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, C.; Oishi, M.; Iwata, Y.; Maekawa, K.; Matsumura, T. Impact of the TRPV2 Inhibitor on Advanced Heart Failure in Patients with Muscular Dystrophy: Exploratory Study of Biomarkers Related to the Efficacy of Tranilast. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiozaki, A.; Kudou, M.; Fujiwara, H.; Konishi, H.; Shimizu, H.; Arita, T.; Kosuga, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Morimura, R.; Ikoma, H.; et al. Clinical safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant combination chemotherapy of tranilast in advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Phase I/II study (TNAC). Medicine 2020, 99, e23633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, O.M.; Martin, S.L.; Sergeant, G.P.; McAuley, D.F.; O’Kane, C.M.; Button, B.; McGarvey, L.P.; Lundy, F.T. TRPV2 modulates mechanically Induced ATP Release from Human bronchial epithelial cells. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, H.; Boudaka, A.; Shibasaki, K.; Yamanaka, A.; Sugiyama, T.; Tominaga, M. Involvement of TRPV2 activation in intestinal movement through nitric oxide production in mice. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 16536–16544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemzehi, M.; Yavari, N.; Rahmani, F.; Asgharzadeh, F.; Soleimani, A.; Shakour, N.; Avan, A.; Hadizadeh, F.; Fakhraie, M.; Marjaneh, R.M.; et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta by Tranilast reduces tumor growth and ameliorates fibrosis in colorectal cancer. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.J.R.; Islam, B.; Ward, S.; Jackson, O.; Armitage, R.; Blackburn, J.; Haider, S.; McHugh, P.C. Repurposing of Tranilast for Potential Neuropathic Pain Treatment by Inhibition of Sepiapterin Reductase in the BH(4) Pathway. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 11960–11972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Menju, T.; Nishikawa, S.; Miyata, R.; Tanaka, S.; Yutaka, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Nakajima, D.; Hamaji, M.; Ohsumi, A.; et al. Tranilast Inhibits TGF-beta1-induced Epithelial-mesenchymal Transition and Invasion/Metastasis via the Suppression of Smad4 in Human Lung Cancer Cell Lines. Anticancer. Res. 2020, 40, 3287–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, T.C.; Ramisch, A.; Pumroy, R.A.; Pantke, S.; Herzog, C.; Echtermeyer, F.G.; Al-Samir, S.; Endeward, V.; Moiseenkova-Bell, V.; Leffler, A. Molecular determinants of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate sensitivity of transient receptor potential vanilloid 2-unexpected differences between 2 rodent orthologs. Mol. Pharmacol. 2025, 107, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, C.; Mulke, P.; Stuhrhahn, T.; Rocereta, J.A.; Pumroy, R.A.; Moiseenkova-Bell, V.; Echtermeyer, F.G.; Leffler, A. Genetic and pharmacological evidence for a role of the ion channel TRPV2 as a regulator of actin-dependent functional traits in rat basophilic leukemia cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1006, 178164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pumroy, R.A.; Protopopova, A.D.; Fricke, T.C.; Lange, I.U.; Haug, F.M.; Nguyen, P.T.; Gallo, P.N.; Sousa, B.B.; Bernardes, G.J.L.; Yarov-Yarovoy, V.; et al. Structural insights into TRPV2 activation by small molecules. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pumroy, R.A.; Samanta, A.; Liu, Y.; Hughes, T.E.; Zhao, S.; Yudin, Y.; Rohacs, T.; Han, S.; Moiseenkova-Bell, V.Y. Molecular mechanism of TRPV2 channel modulation by cannabidiol. eLife 2019, 8, e48792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.Z.; Gu, Q.; Wang, C.; Colton, C.K.; Tang, J.; Kinoshita-Kawada, M.; Lee, L.Y.; Wood, J.D.; Zhu, M.X. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate is a common activator of TRPV1, TRPV2, and TRPV3. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 35741–35748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Neeper, M.P.; Liu, Y.; Hutchinson, T.L.; Lubin, M.L.; Flores, C.M. TRPV2 is activated by cannabidiol and mediates CGRP release in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 6231–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Ding, N.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Wen, J.; Sun, W.; Zu, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Activation of Piezo1 or TRPV2 channels inhibits human ureteral contractions via NO release from the mucosa. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1410565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neeper, M.P.; Liu, Y.; Hutchinson, T.L.; Wang, Y.; Flores, C.M.; Qin, N. Activation properties of heterologously expressed mammalian TRPV2: Evidence for species dependence. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 15894–15902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, T.C.; Echtermeyer, F.; Zielke, J.; de la Roche, J.; Filipovic, M.R.; Claverol, S.; Herzog, C.; Tominaga, M.; Pumroy, R.A.; Moiseenkova-Bell, V.Y.; et al. Oxidation of methionine residues activates the high-threshold heat-sensitive ion channel TRPV2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 24359–24365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyachi, Y.; Imamura, S.; Niwa, Y. The effect of tranilast of the generation of reactive oxygen species. J. Pharmacobiodyn 1987, 10, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schluter, F.; Leffler, A. Oxidation differentially modulates the recombinant voltage-gated Na(+) channel alpha-subunits Nav1.7 and Nav1.8. Brain Res. 2016, 1648, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.E.; Kim, D.Y.; Choi, M.J.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, O.H.; Lee, J.; Seo, E.; Cheon, H.G. Tranilast protects pancreatic beta-cells from palmitic acid-induced lipotoxicity via FoxO-1 inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shen, Q. Tranilast reduces cardiomyocyte injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion via Nrf2/HO-1/NF-kappaB signaling. Exp. Ther. Med. 2023, 25, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Tanaka, H.; Kawada, K.; Nagai, H.; Koda, A. Suppressive effects of tranilast on pulmonary fibrosis and activation of alveolar macrophages in mice treated with bleomycin: Role of alveolar macrophages in the fibrosis. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 67, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashio, M.; Sokabe, T.; Shintaku, K.; Uematsu, T.; Fukuta, N.; Kobayashi, N.; Mori, Y.; Tominaga, M. Redox signal-mediated sensitization of transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) to temperature affects macrophage functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6745–6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, A.; Gao, X.P.; Qian, F.; Kawamura, T.; Han, J.; Hecquet, C.; Ye, R.D.; Vogel, S.M.; Malik, A.B. The redox-sensitive cation channel TRPM2 modulates phagocyte ROS production and inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 13, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradding, P.; Okayama, Y.; Kambe, N.; Saito, H. Ion channel gene expression in human lung, skin, and cord blood-derived mast cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2003, 73, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikai, K.; Ujihara, M.; Fujii, K.; Urade, Y. Inhibitory effect of tranilast on prostaglandin D synthetase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1989, 38, 2673–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Gong, Z.; Zhao, J.; Ren, P.; Yu, Z.; Su, N.; Gong, L.; Mao, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, S.; et al. Prostaglandin D(2) is involved in the regulation of inflammatory response in Staphylococcus aureus-infected mice macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 129, 111526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; Talukdar, S.; Bae, E.J.; Imamura, T.; Morinaga, H.; Fan, W.; Li, P.; Lu, W.J.; Watkins, S.M.; Olefsky, J.M. GPR120 is an omega-3 fatty acid receptor mediating potent anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Cell 2010, 142, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrabalan, A.; McPhillie, M.J.; Morice, A.H.; Boa, A.N.; Sadofsky, L.R. N-Cinnamoylanthranilates as human TRPA1 modulators: Structure-activity relationships and channel binding sites. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 170, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassmann, M.; Hansel, A.; Leipold, E.; Birkenbeil, J.; Lu, S.Q.; Hoshi, T.; Heinemann, S.H. Oxidation of multiple methionine residues impairs rapid sodium channel inactivation. Pflug. Arch. 2008, 456, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fricke, T.C.; Stein, N.; Herzog, C.; Echtermeyer, F.G.; Leffler, A. Tranilast Does Not Inhibit TRPV2. Cells 2026, 15, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010013

Fricke TC, Stein N, Herzog C, Echtermeyer FG, Leffler A. Tranilast Does Not Inhibit TRPV2. Cells. 2026; 15(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleFricke, Tabea C., Nele Stein, Christine Herzog, Frank G. Echtermeyer, and Andreas Leffler. 2026. "Tranilast Does Not Inhibit TRPV2" Cells 15, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010013

APA StyleFricke, T. C., Stein, N., Herzog, C., Echtermeyer, F. G., & Leffler, A. (2026). Tranilast Does Not Inhibit TRPV2. Cells, 15(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010013