Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote Platelet-Driven Contraction of Inflammatory Blood Clots via Local Generation of Endogenous Thrombin and Softening of the Fibrin Network

Highlights

- Activated neutrophils promote blood clot contraction, and this effect is associated with formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) embedded in the fibrin network.

- NETs stimulated clot contraction by enhancing the production of endogenous thrombin and reducing the stiffness of blood clots.

- The results obtained provide novel mechanistic insights into the pathophysiology of inflammatory thrombosis, suggesting that the presence of NETs creates a unique thrombus phenotype with enhanced contractility.

- This finding may have important implications for understanding thrombotic complications in sepsis, COVID-19, and other inflammatory conditions, potentially guiding the development of future therapeutic strategies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Blood Collection and Fractionation

2.2. Isolation and Activation of Neutrophils to Produce Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs)

2.3. Flow Cytometry of Isolated Neutrophils

2.4. (Immuno)Histochemical Examination of PMA-Activated Neutrophils and NETs

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy of Neutrophils and NETs

2.6. Blood Clot Contraction Assay

2.7. Thromboelastography (TEG)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

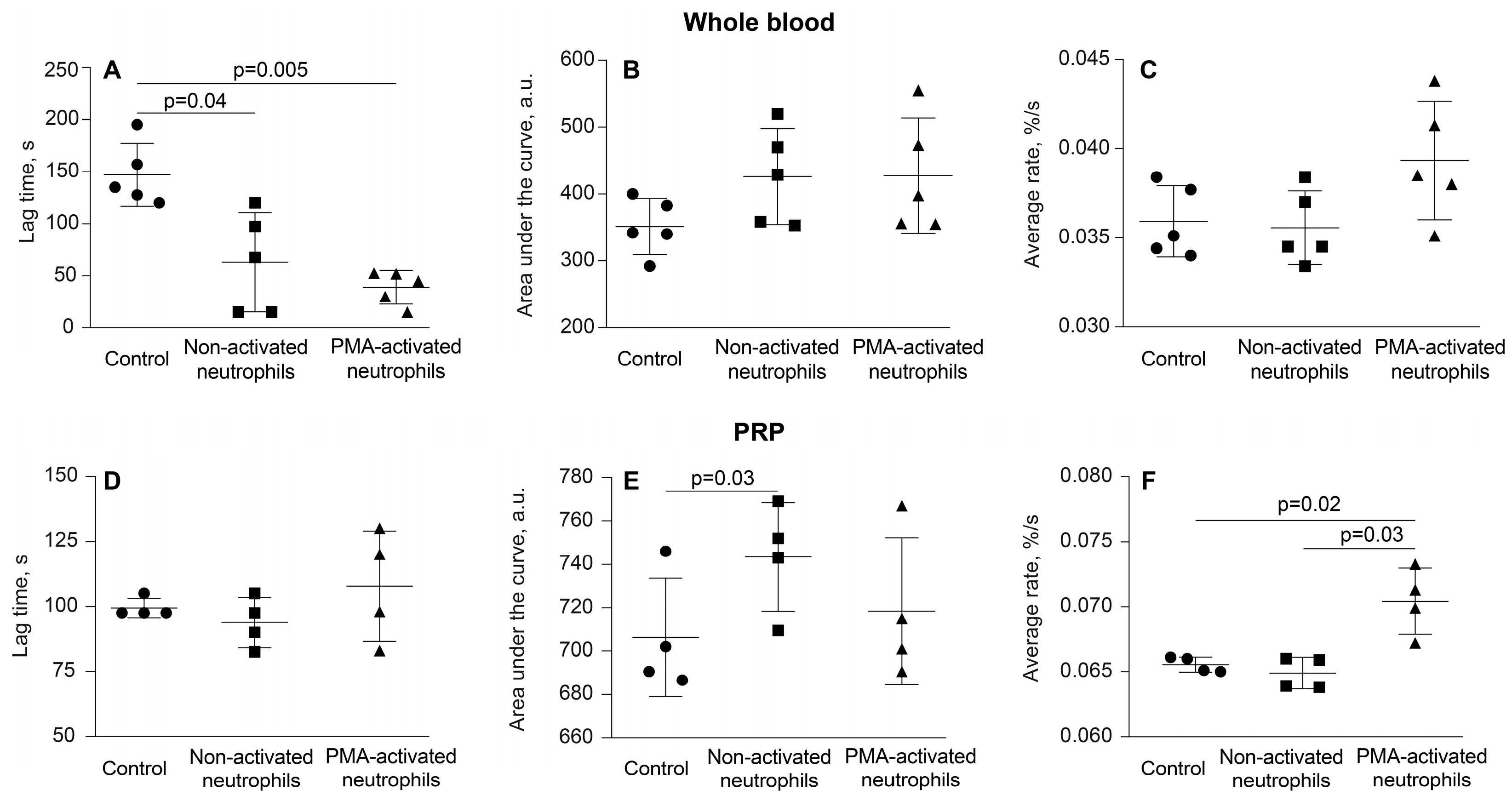

3.1. Activated Neutrophils Promote Clot Contraction

3.2. Activated Neutrophils Affect the Phase Kinetics of Clot Contraction

3.3. PMA-Activated Neutrophils Produce NETs

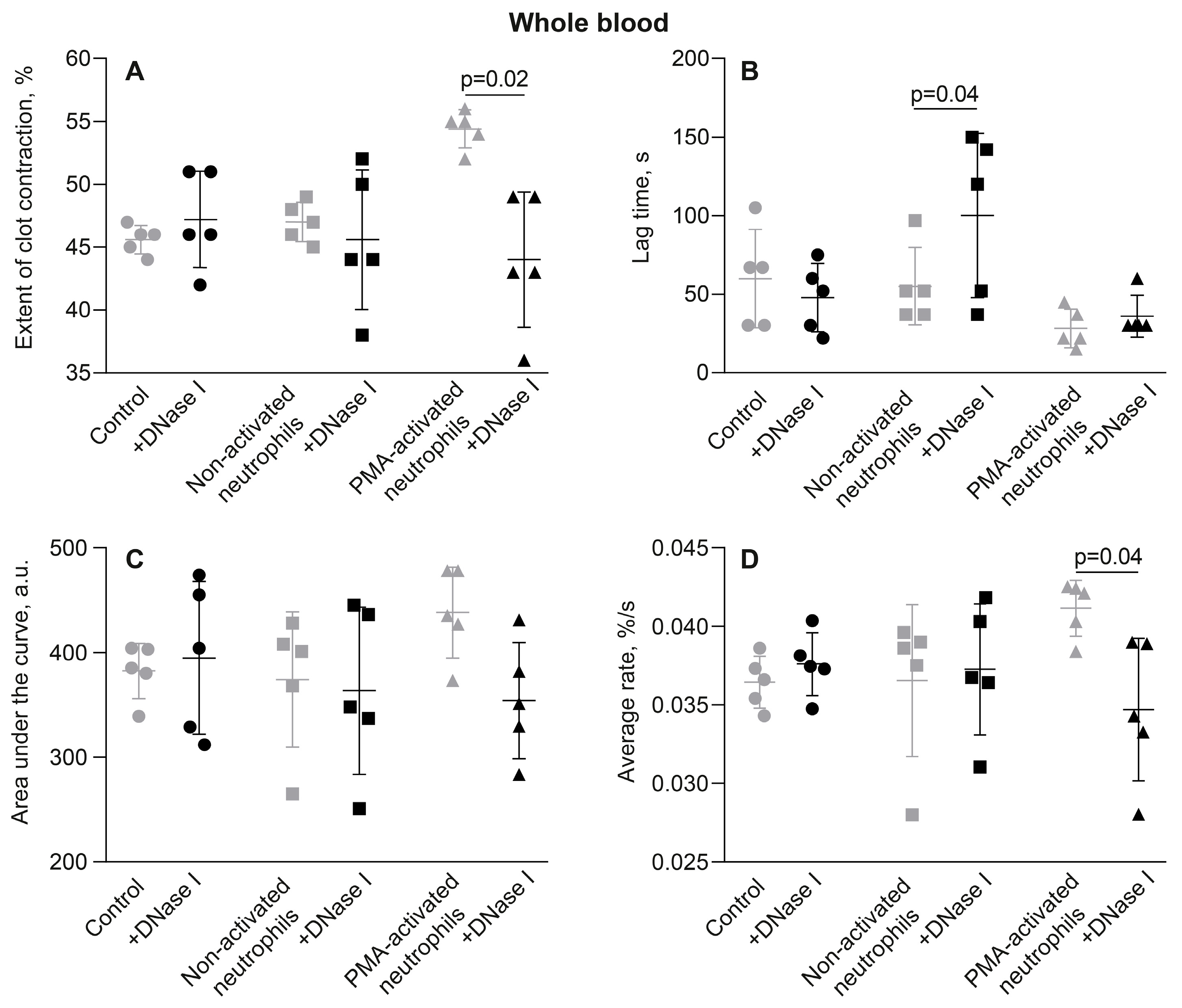

3.4. The Effects of Activated Neutrophils on Clot Contraction Are Associated with NETs Embedded in a Clot

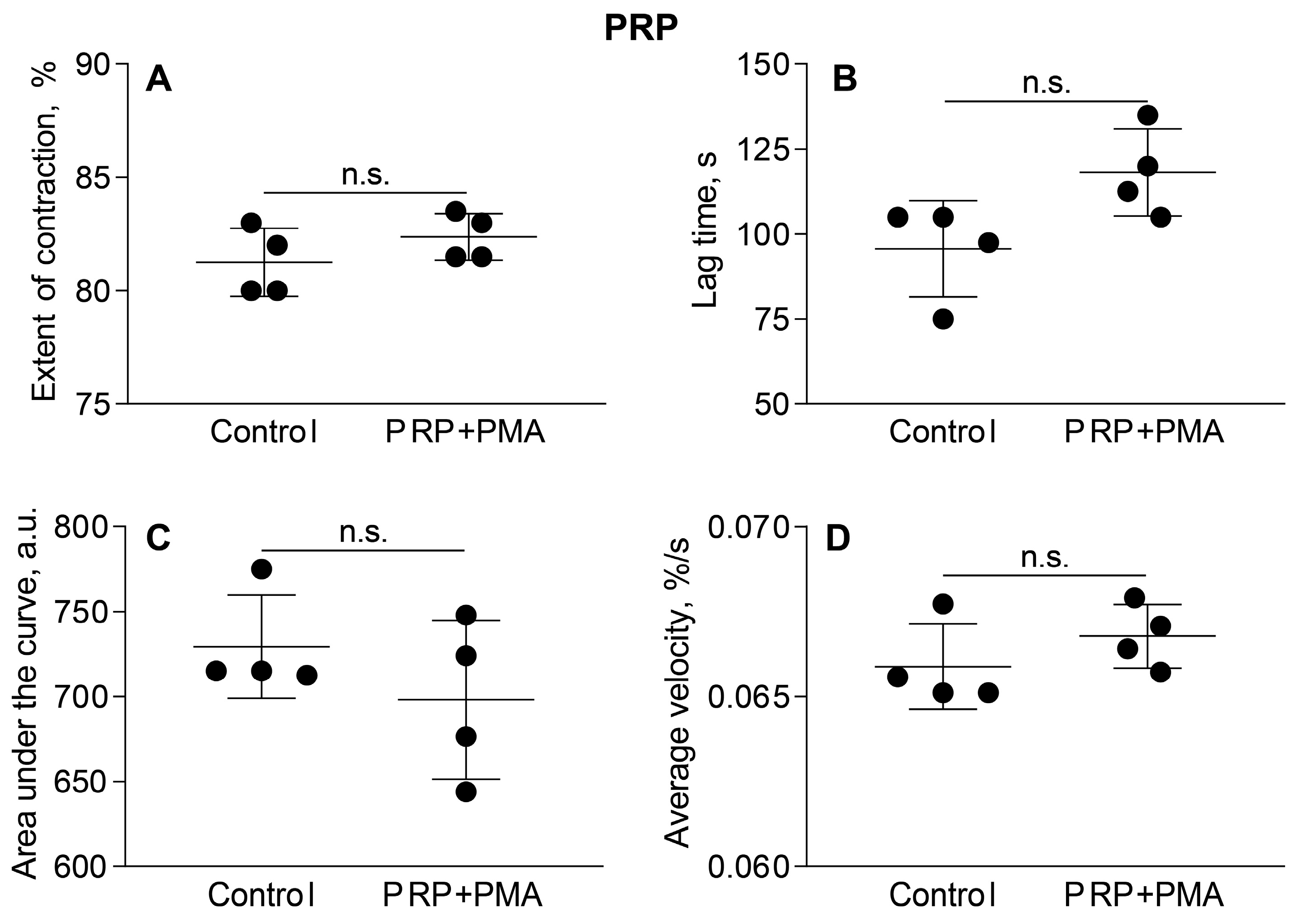

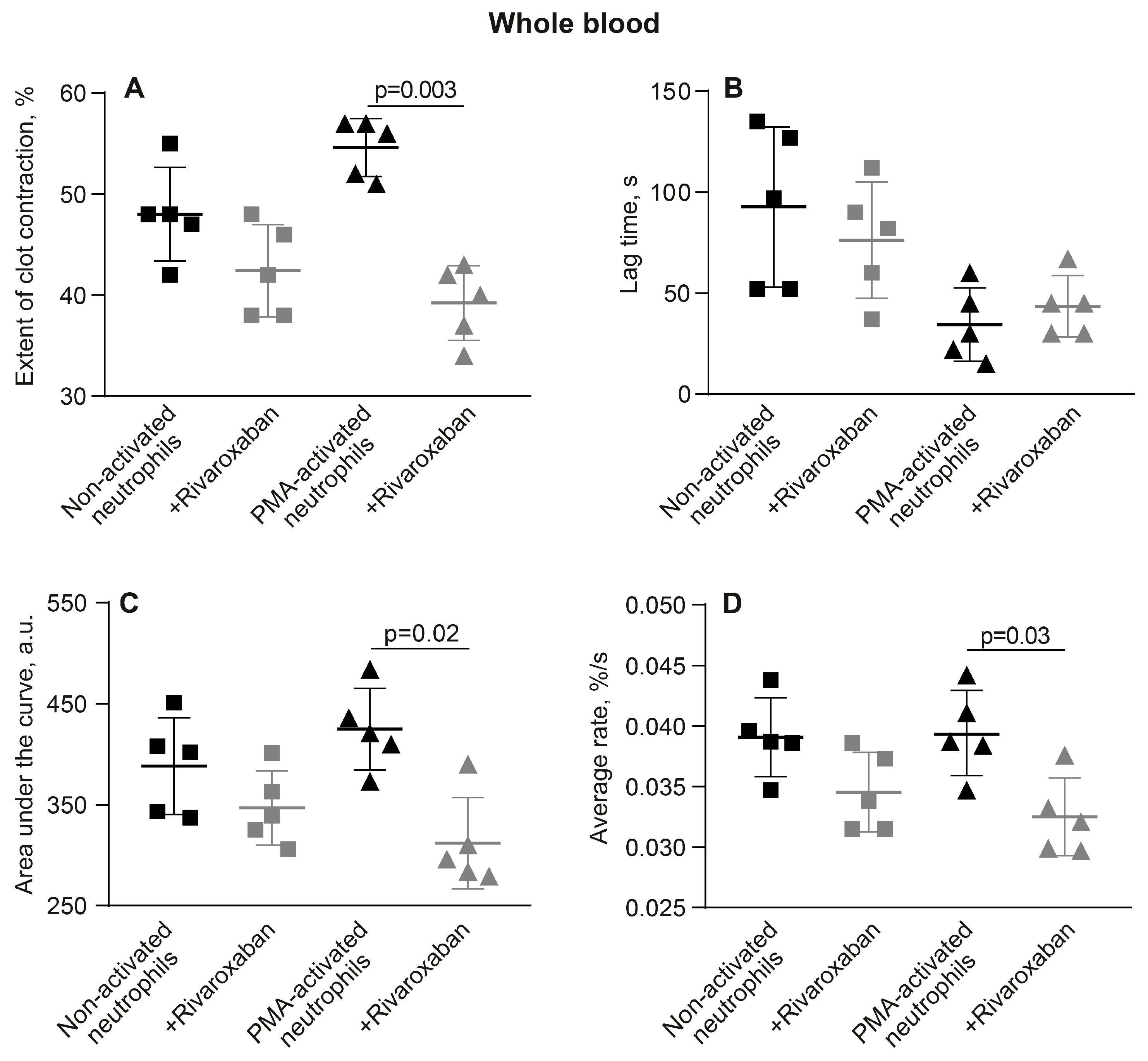

3.5. The Promotion of Clot Contraction by NETs Is Mediated by Enhanced Generation of Endogenous Thrombin

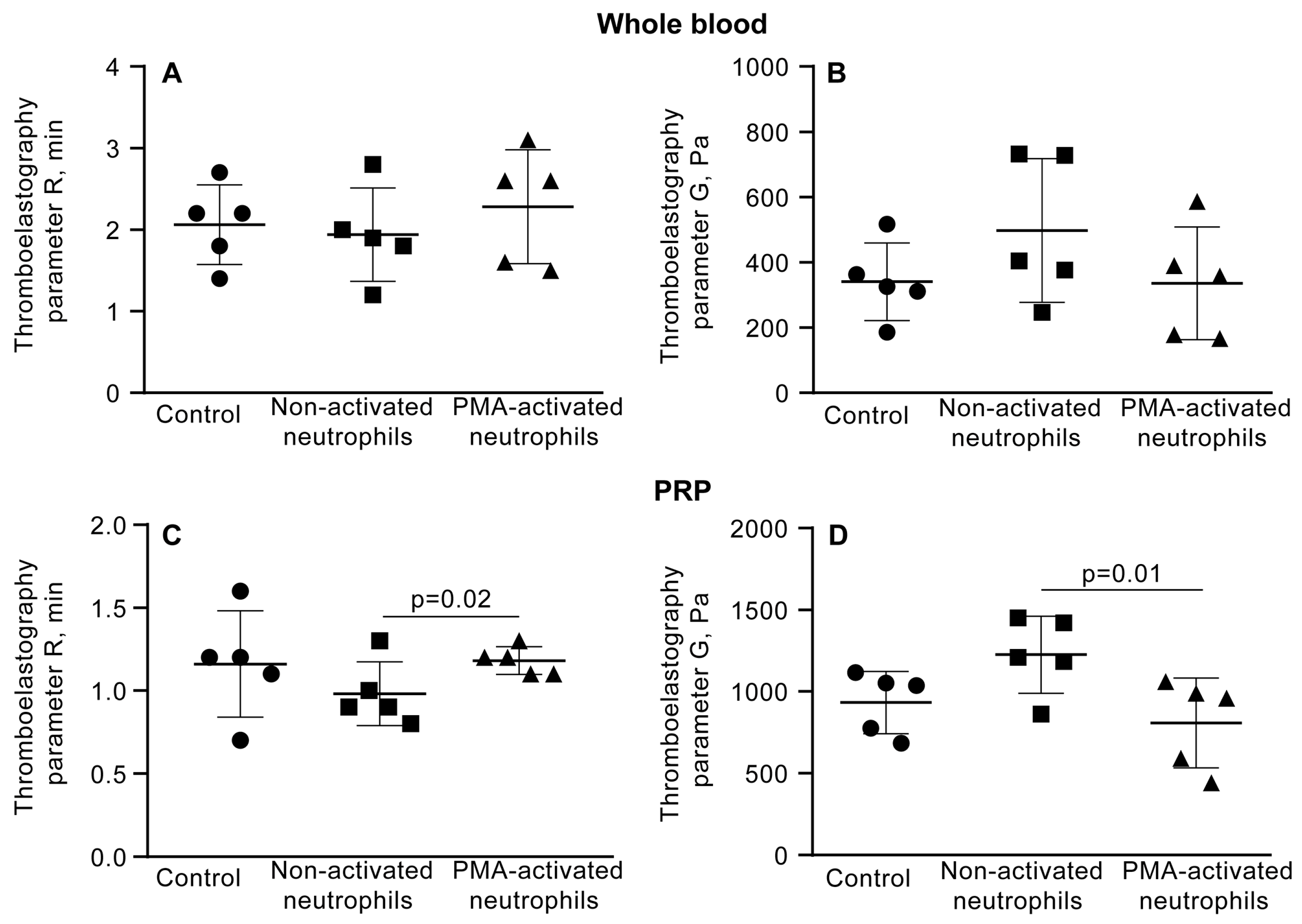

3.6. NETs Make the Fibrin Clot Softer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NETs | Neutrophil extracellular traps |

| PMA | Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| DNAse I | Deoxyribonuclease I |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| RBCs | Red blood cells |

| PPP | Platelet-poor plasma |

| PFP | Platelet-free plasma |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| HBSS | Hanks’ balanced salt solution |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline |

| TEG | Thromboelastography |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| R | Reaction time |

| G’ | Storage (elastic) modulus |

| MA | Maximal amplitude |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| PAD4 | Peptidylarginine deiminase type 4 |

References

- Engelmann, B.; Massberg, S. Thrombosis as an Intravascular Effector of Innate Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Willey, J. The Interplay Between Inflammation and Thrombosis in COVID-19: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Strategies, and Challenges. Thromb. Update 2022, 8, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrottmaier, W.C.; Assinger, A. The Concept of Thromboinflammation. Hamostaseologie 2024, 44, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, T.A.; Brill, A.; Duerschmied, D.; Schatzberg, D.; Monestier, M.; Myers, D.D., Jr.; Wrobleski, S.K.; Wakefield, T.W.; Hartwig, J.H.; Wagner, D.D. Extracellular DNA Traps Promote Thrombosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15880–15885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; Weinrauch, Y.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Kill Bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinod, K.; Wagner, D.D. Thrombosis: Tangled Up in NETs. Blood 2014, 123, 2768–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Myers, D.R.; Nikolov, S.V.; Oshinowo, O.; Baek, J.; Bowie, S.M.; Lambert, T.P.; Woods, E.; Sakurai, Y.; Lam, W.A.; et al. Platelet Heterogeneity Enhances Blood Clot Volumetric Contraction: An Example of Asynchrono-Mechanical Amplification. Biomaterials 2021, 274, 120828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.E., Jr. Development of Platelet Contractile Force as a Research and Clinical Measure of Platelet Function. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2003, 38, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.R.; Qiu, Y.; Fay, M.E.; Tennenbaum, M.; Chester, D.; Cuadrado, J.; Sakurai, Y.; Baek, J.; Tran, R.; Ciciliano, J.C.; et al. Single-Platelet Nanomechanics Measured by High-Throughput Cytometry. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cines, D.B.; Lebedeva, T.; Nagaswami, C.; Hayes, V.; Massefski, W.; Litvinov, R.I.; Rauova, L.; Lowery, T.J.; Weisel, J.W. Clot Contraction: Compression of Erythrocytes into Tightly Packed Polyhedra and Redistribution of Platelets and Fibrin. Blood 2014, 123, 1596–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalker, T.J.; Welsh, J.D.; Tomaiuolo, M.; Wu, J.; Colace, T.V.; Diamond, S.L.; Brass, L.F. A Systems Approach to Hemostasis: 3. Thrombus Consolidation Regulates Intrathrombus Solute Transport and Local Thrombin Activity. Blood 2014, 124, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinov, R.I.; Weisel, J.W. Blood Clot Contraction: Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Disease. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 7, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutwiler, V.; Litvinov, R.I.; Lozhkin, A.P.; Peshkova, A.D.; Lebedeva, T.; Ataullakhanov, F.I.; Spiller, K.L.; Cines, D.B.; Weisel, J.W. Kinetics and Mechanics of Clot Contraction Are Governed by the Molecular and Cellular Composition of the Blood. Blood 2016, 127, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, B.J.; Adrover, J.M.; Baxter-Stoltzfus, A.; Borczuk, A.; Cools-Lartigue, J.; Crawford, J.M.; Daßler-Plenker, J.; Guerci, P.; Huynh, C.; Knight, J.S.; et al. Targeting Potential Drivers of COVID-19: Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20200652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.L.; Dunster, J.L.; Kriek, N.; Unsworth, A.J.; Sage, T.; Mohammed, Y.M.M.; De Simone, I.; Taylor, K.A.; Bye, A.P.; Ólafsson, G.; et al. The Rate of Platelet Activation Determines Thrombus Size and Structure at Arterial Shear. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 21, 2248–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.A.; Abed, U.; Goosmann, C.; Hurwitz, R.; Schulze, I.; Wahn, V.; Weinrauch, Y.; Brinkmann, V.; Zychlinsky, A. Novel Cell Death Program Leads to Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 176, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraro, S.P.; De Souza, G.F.; Gallo, S.W.; Da Silva, B.K.; De Oliveira, S.D.; Vinolo, M.A.R.; Saraiva, E.M.; Porto, B.N. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Induces the Classical ROS-Dependent NETosis Through PAD-4 and Necroptosis Pathways Activation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onouchi, T.; Shiogama, K.; Matsui, T.; Mizutani, Y.; Sakurai, K.; Inada, K.; Tsutsumi, Y. Visualization of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Fibrin Meshwork in Human Fibrinopurulent Inflammatory Lesions: II. Ultrastructural Study. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 2016, 49, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.E., Jr.; Martin, E.J.; Carr, S.L. Delayed, Reduced or Inhibited Thrombin Production Reduces Platelet Contractile Force and Results in Weaker Clot Formation. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2002, 13, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, K.; Massberg, S. Interplay Between Inflammation and Thrombosis in Cardiovascular Pathology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noubouossie, D.F.; Reeves, B.N.; Strahl, B.D.; Key, N.S. Neutrophils: Back in the Thrombosis Spotlight. Blood 2019, 133, 2186–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thålin, C.; Hisada, Y.; Lundström, S.; Mackman, N.; Wallén, H. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: Villains and Targets in Arterial, Venous, and Cancer-Associated Thrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 1724–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Yalavarthi, S.; Shi, H.; Gockman, K.; Zuo, M.; Madison, J.A.; Blair, C.; Weber, A.; Barnes, B.J.; Egeblad, M.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e138999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisel, J.W.; Litvinov, R.I. Exploring the Thrombus Niche: Lessons Learned and Potential Therapeutic Opportunities. Blood 2025, 146, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plow, E.F. The Contribution of Leukocyte Proteases to Fibrinolysis. Blut 1986, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemzadeh, M.; Hosseini, E. Intravascular Leukocyte Migration through Platelet Thrombi: Directing Leukocytes to Sites of Vascular Injury. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 113, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducroux, C.; Di Meglio, L.; Loyau, S.; Delbosc, S.; Boisseau, W.; Deschildre, C.; Ben Maacha, M.; Blanc, R.; Redjem, H.; Ciccio, G.; et al. Thrombus Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Content Impair tPA-Induced Thrombolysis in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2018, 49, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, A.S.; Martinod, K.; Seidman, M.A.; Wong, S.L.; Borissoff, J.I.; Piazza, G.; Libby, P.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Mitchell, R.N.; Wagner, D.D. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Form Predominantly During the Organizing Stage of Human Venous Thromboembolism Development. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laridan, E.; Denorme, F.; Desender, L.; François, O.; Andersson, T.; Deckmyn, H.; Vanhoorelbeke, K.; De Meyer, S.F. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Ischemic Stroke Thrombi. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 82, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, A.; Alias, S.; Scherz, T.; Hofbauer, M.; Jakowitsch, J.; Panzenböck, A.; Simon, D.; Laimer, D.; Bangert, C.; Kammerlander, A.; et al. Coronary Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Burden and Deoxyribonuclease Activity in ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Are Predictors of ST-Segment Resolution and Infarct Size. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, T.J.; Vu, T.T.; Swystun, L.L.; Dwivedi, D.J.; Mai, S.H.; Weitz, J.I.; Liaw, P.C. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote Thrombin Generation Through Platelet-Dependent and Platelet-Independent Mechanisms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Brühl, M.L.; Stark, K.; Steinhart, A.; Chandraratne, S.; Konrad, I.; Lorenz, M.; Khandoga, A.; Tirniceriu, A.; Coletti, R.; Köllnberger, M.; et al. Monocytes, Neutrophils, and Platelets Cooperate to Initiate and Propagate Venous Thrombosis in Mice In Vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 819–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshkova, A.D.; Le Minh, G.; Tutwiler, V.; Andrianova, I.A.; Weisel, J.W.; Litvinov, R.I. Activated Monocytes Enhance Platelet-Driven Contraction of Blood Clots via Tissue Factor Expression. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semeraro, F.; Ammollo, C.T.; Morrissey, J.H.; Dale, G.L.; Friese, P.; Esmon, N.L.; Esmon, C.T. Extracellular Histones Promote Thrombin Generation Through Platelet-Dependent Mechanisms: Involvement of Platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood 2011, 118, 1952–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massberg, S.; Grahl, L.; von Bruehl, M.L.; Manukyan, D.; Pfeiler, S.; Goosmann, C.; Brinkmann, V.; Lorenz, M.; Bidzhekov, K.; Khandagale, A.B.; et al. Reciprocal Coupling of Coagulation and Innate Immunity via Neutrophil Serine Proteases. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, W.; Ruggeri, Z.M. Neutrophils Release Brakes of Coagulation. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 851–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowicz, E.; Farkas, V.J.; Szabó, L.; Cherrington, S.; Thelwell, C.; Kolev, K. DNA and Histones Impair the Mechanical Stability and Lytic Susceptibility of Fibrin Formed by Staphylocoagulase. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1233128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longstaff, C.; Varjú, I.; Sótonyi, P.; Szabó, L.; Krumrey, M.; Hoell, A.; Bóta, A.; Varga, Z.; Komorowicz, E.; Kolev, K. Mechanical Stability and Fibrinolytic Resistance of Clots Containing Fibrin, DNA, and Histones. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 6946–6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, T.W.; Myers, D.D.; Henke, P.K. Mechanisms of Venous Thrombosis and Resolution. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutwiler, V.; Peshkova, A.D.; Le Minh, G.; Zaitsev, S.; Litvinov, R.I.; Cines, D.B.; Weisel, J.W. Blood Clot Contraction Differentially Modulates Internal and External Fibrinolysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 17, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henke, P.K.; Wakefield, T. Thrombus Resolution and Vein Wall Injury: Dependence on Chemokines and Leukocytes. Thromb. Res. 2009, 123, S72–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Humphries, J.; Modarai, B.; Mattock, K.; Waltham, M.; Evans, C.E.; Ahmad, A.; Patel, A.S.; Premaratne, S.; Lyons, O.T.; et al. Leukocytes and the Natural History of Deep Vein Thrombosis: Current Concepts and Future Directions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, K.; Machovich, R. Molecular and Cellular Modulation of Fibrinolysis. Thromb. Haemost. 2003, 89, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Alcázar, M.; Rangaswamy, C.; Panda, R.; Bitterling, J.; Simsek, Y.J.; Long, A.T.; Bilyy, R.; Krenn, V.; Renné, C.; Renné, T.; et al. Host DNases Prevent Vascular Occlusion by Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Science 2017, 358, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Globisch, M.A.; Onyeogaziri, F.C.; Smith, R.O.; Arce, M.; Magnusson, P.U. Dysregulated Hemostasis and Immunothrombosis in Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 20, 12575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peshkova, A.D.; Malyasyov, D.V.; Bredikhin, R.A.; Le Minh, G.; Andrianova, I.A.; Tutwiler, V.; Nagaswami, C.; Weisel, J.W.; Litvinov, R.I. Reduced Contraction of Blood Clots in Venous Thromboembolism Is a Potential Thrombogenic and Embologenic Mechanism. TH Open 2018, 2, e104–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varjú, I.; Longstaff, C.; Szabó, L.; Farkas, Á.Z.; Varga-Szabó, V.J.; Tanka-Salamon, A.; Machovich, R.; Kolev, K. DNA, Histones and Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Exert Anti-Fibrinolytic Effects in a Plasma Environment. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 113, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Guo, P.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Lan, C.; Xian, J.; Ge, M.; Feng, H.; Chen, Z. Targeting Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Enhanced tPA Fibrinolysis for Experimental Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Transl. Res. 2019, 211, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Patil, G.; Dayal, S. NLRP3-Induced NETosis: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Ischemic Thrombotic Diseases? Cells 2023, 12, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, J.P.; Allali, Y.; Lesty, C.; Tanguy, M.L.; Silvain, J.; Ankri, A.; Blanchet, B.; Dumaine, R.; Gianetti, J.; Payot, L.; et al. Altered Fibrin Architecture Is Associated with Hypofibrinolysis and Premature Coronary Atherothrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 2567–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wufsus, A.R.; Macera, N.E.; Neeves, K.B. The Hydraulic Permeability of Blood Clots as a Function of Fibrin and Platelet Density. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, 1812–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borissoff, J.I.; Joosen, I.A.; Versteylen, M.O.; Brill, A.; Fuchs, T.A.; Savchenko, A.S.; Gallant, M.; Martinod, K.; Ten Cate, H.; Hofstra, L.; et al. Elevated Levels of Circulating DNA and Chromatin Are Independently Associated with Severe Coronary Atherosclerosis and a Prothrombotic State. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 2032–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, J.S.; Luo, W.; O’Dell, A.A.; Yalavarthi, S.; Zhao, W.; Subramanian, V.; Guo, C.; Grenn, R.C.; Thompson, P.R.; Eitzman, D.T.; et al. Peptidylarginine Deiminase Inhibition Reduces Vascular Damage and Modulates Innate Immune Responses in Murine Models of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laridan, E.; Martinod, K.; De Meyer, S.F. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Arterial and Venous Thrombosis. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2019, 45, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Maat, M.P.; van Schie, M.; Kluft, C.; Leebeek, F.W.; Meijer, P. Biological Variation of Hemostasis Variables in Thrombosis and Bleeding: Consequences for Performance Specifications. Clin. Chem. 2016, 62, 1639–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, J.E.; Nahrendorf, M.; Kim, D.E. Direct Thrombus Imaging in Stroke. J. Stroke 2016, 3, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabnis, R.W. Novel Peptidylarginine Deiminase Type 4 (PAD4) Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 1537–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, S.G.; Grimes, T.; Munro, S.; Zarganes-Tzitzikas, T.; La Thangue, N.B.; Brennan, P.E. A Patent Review of Peptidylarginine Deiminase 4 (PAD4) Inhibitors (2014–Present). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2025, 35, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiocchi, S.; Burnham, E.E.; Cartaya, A.; Lisi, V.; Buechler, N.; Pollard, R.; Babaki, D.; Bergmeier, W.; Pinkerton, N.M.; Bahnson, E.M. Development of DNase-1 Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles Synthesized by Inverse Flash Nanoprecipitation for Neutrophil-Mediated Drug Delivery to In Vitro Thrombi. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2404584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilha, C.S.; Veras, F.P.; Dos Santos Ramos, A.; Gomes, G.F.; Rodrigues Lemes, R.M.; Arruda, E.; Alves-Filho, J.C.; Cunha, T.M.; Cunha, F.Q. PAD4 inhibition impacts immune responses in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2025, 4, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saliakhutdinova, S.M.; Khismatullin, R.R.; Khabirova, A.I.; Litvinov, R.I.; Weisel, J.W. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote Platelet-Driven Contraction of Inflammatory Blood Clots via Local Generation of Endogenous Thrombin and Softening of the Fibrin Network. Cells 2025, 14, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242018

Saliakhutdinova SM, Khismatullin RR, Khabirova AI, Litvinov RI, Weisel JW. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote Platelet-Driven Contraction of Inflammatory Blood Clots via Local Generation of Endogenous Thrombin and Softening of the Fibrin Network. Cells. 2025; 14(24):2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242018

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaliakhutdinova, Shakhnoza M., Rafael R. Khismatullin, Alina I. Khabirova, Rustem I. Litvinov, and John W. Weisel. 2025. "Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote Platelet-Driven Contraction of Inflammatory Blood Clots via Local Generation of Endogenous Thrombin and Softening of the Fibrin Network" Cells 14, no. 24: 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242018

APA StyleSaliakhutdinova, S. M., Khismatullin, R. R., Khabirova, A. I., Litvinov, R. I., & Weisel, J. W. (2025). Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote Platelet-Driven Contraction of Inflammatory Blood Clots via Local Generation of Endogenous Thrombin and Softening of the Fibrin Network. Cells, 14(24), 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242018