Distinct Roles of Monocyte Subsets in Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Monocyte Biology and Subsets

3.1. Monopoiesis

3.2. Monocyte Heterogeneity

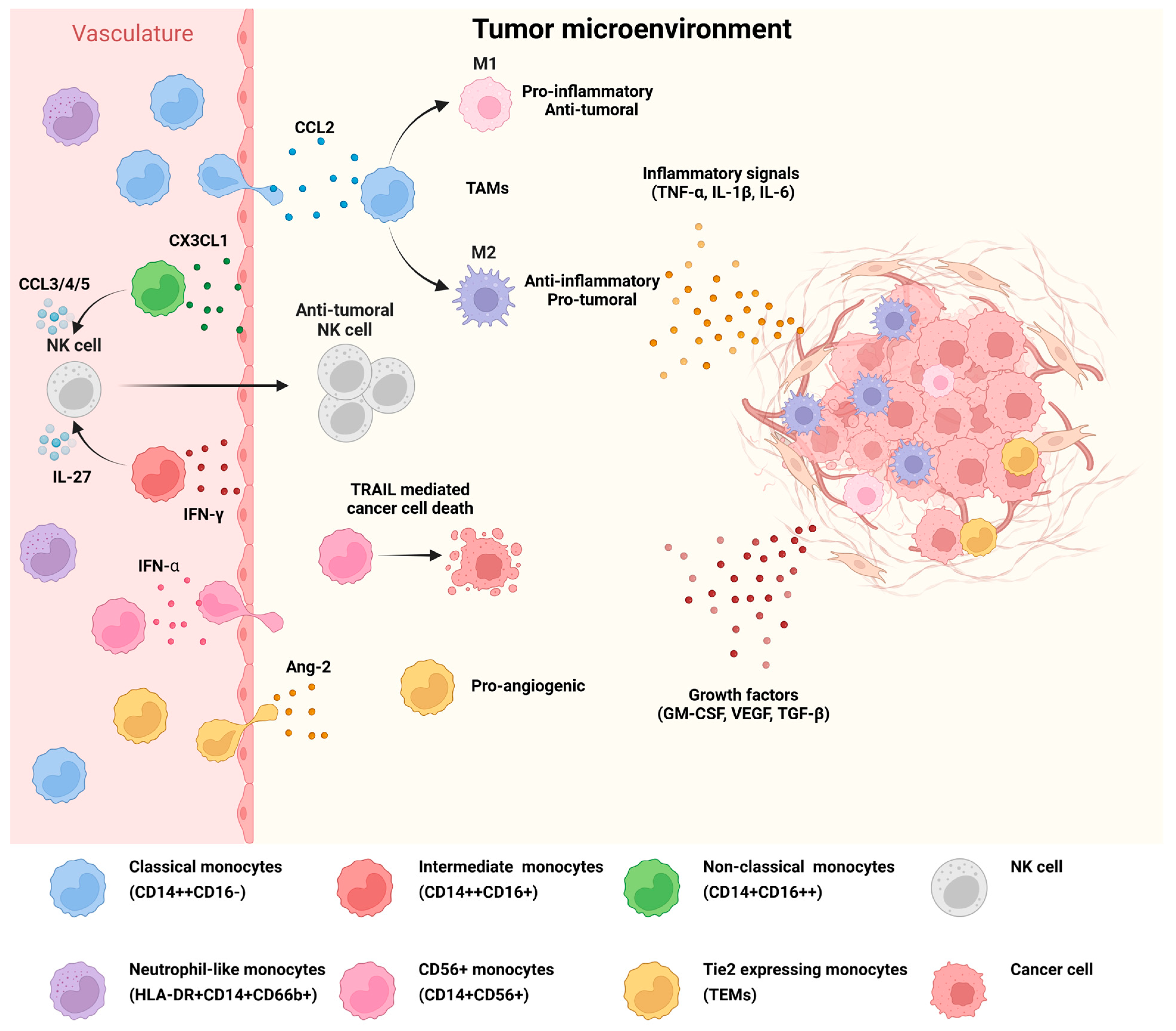

4. The Effect of Monocyte Subsets in Cancer

4.1. Monocyte Recruitment to Tumor Sites

4.2. Reprogramming of Monocyte Subsets to Promote Tumorigenesis

| Monocyte Subset | Phenotype | Function | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical (CD14++CD16−) | Anti-tumoral (M1 phenotype) | Production of inflammatory cytokines Induction of cancer cell death Activation of anti-tumoral CD8+ T cells | [50,55,56] |

| Pro-tumoral (Mo-MDSCs or M2 phenotype) | Production of anti-inflammatory cytokines Support of tumor angiogenesis Inhibition of T cell anti-tumoral response | [27,57,67,68,69,70] | |

| Non-classical (CD14+CD16++) | Anti-tumoral | Patrolling of the vasculature and engulfment of tumor material Recruitment and activation of NK cells Activation of CD8+ T cells | [59,60,61,62] |

| Intermediate (CD14++CD16+) | Anti-tumoral | IFN-γ-activated monocytes induce NK cell expansion | [64] |

| Pro-tumoral | C5a-activated monocytes support tumor proliferation, cell survival, migration, and EMT | [65] | |

| TEMs (Tie2-expressing monocytes) | Pro-tumoral | Drivers of tumor angiogenesis and tissue remodeling by the release of growth factors | [43,44,76,77] |

| Neutrophil-like monocytes (HLA-A2+ CD14+CD66b+) | Pro-tumoral | Induction of NK cell dysfunction via IL-10 secretion | [48,78] |

| Anti-tumoral | Co-stimulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation | [47] | |

| CD56+ monocytes (CD14+CD56+) | Anti-tumoral | Tumor cell lysis via the TRAIL signal T cell activation | [11] |

4.3. Monocyte Contribution to Cancer Progression and Metastasis

5. Monocytes as Cancer Biomarkers and Their Subset-Specific Responses to Therapy

5.1. Circulating Monocytes as Biomarkers for Disease Development, Stage, and Prognosis

| Cancer Type | Monocyte Subset | Diagnostic and Prognostic Information | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Non-classical monocyte increase | Inverse correlation between non-classical monocyte count and tumor size | [89] |

| Intermediate monocyte increase | Correlation with a high amount of circulating tumor cells and poor prognosis | [90] | |

| Ovarian cancer | Intermediate monocyte increase | Association with CD8+ T cell inhibition and poor prognosis | [94] |

| Colorectal cancer | Intermediate monocyte increase | Observed at early stages of cancer development as opposed to tumor metastasis | [35] |

| Several cancer types | TEM increase | Correlation with cancer progression and poor prognosis | [12,42,76,77,96] |

| Neutrophil-like monocyte increase | Correlation with tumor development; uncommon in healthy individuals | [47,67] | |

| CD56+ monocyte increase | Observed at early stages of cancer development | [11] | |

| Mo-MDSC elevation | Correlation with cancer progression and poor prognosis | [70,71] |

5.2. Monocyte Effects in Tumor Therapy

6. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ang-2 | Angiopoietin 2 |

| CCL2 | C-C Chemokine Ligand 2 |

| CCR2 | C-C Chemokine Receptor 2 |

| CDP | Common Dendritic Cell Progenitor |

| cMoP | Committed Monocyte Progenitor |

| CMP | Common Myeloid Progenitor |

| CX3CR1 | C-X3-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 1 |

| DC | Dendritic Cell |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte–Monocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| GMP | Granulocyte–Monocyte Progenitor |

| GP | Granulocyte Progenitor |

| HSPC | Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MDP | Monocyte–Dendritic Cell Progenitor |

| MMP | Matrix Metalloproteinase |

| moDC | Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cell |

| Mo-MDSC | Monocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell |

| MP | Monocyte Progenitor |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| TAM | Tumor-Associated Macrophage |

| TEM | Tie2 Expressing Monocyte |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| TIGIT | T cell Immunoreceptor with Immunoglobulin and ITIM Domain |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| TRAIL | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Dash, S.P.; Gupta, S.; Sarangi, P.P. Monocytes and Macrophages: Origin, Homing, Differentiation, and Functionality during Inflammation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austermann, J.; Roth, J.; Barczyk-Kahlert, K. The Good and the Bad: Monocytes’ and Macrophages’ Diverse Functions in Inflammation. Cells 2022, 11, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboelella, N.S.; Brandle, C.; Kim, T.; Ding, Z.C.; Zhou, G. Oxidative Stress in the Tumor Microenvironment and Its Relevance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Weng, J.; You, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wen, J.; Xia, Z.; Huang, S.; Luo, P.; Cheng, Q. Oxidative Stress in Cancer: From Tumor and Microenvironment Remodeling to Therapeutic Frontiers. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.A.; Yáñez, A.; Barman, P.K.; Goodridge, H.S. The Ontogeny of Monocyte Subsets. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock, L.; Ancuta, P.; Crowe, S.; Dalod, M.; Grau, V.; Hart, D.N.; Leenen, P.J.M.; Liu, Y.J.; MacPherson, G.; Randolph, G.J.; et al. Nomenclature of Monocytes and Dendritic Cells in Blood. Blood 2010, 116, e74–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yona, S.; Kim, K.W.; Wolf, Y.; Mildner, A.; Varol, D.; Breker, M.; Strauss-Ayali, D.; Viukov, S.; Guilliams, M.; Misharin, A.; et al. Fate Mapping Reveals Origins and Dynamics of Monocytes and Tissue Macrophages under Homeostasis. Immunity 2013, 38, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geissmann, F.; Jung, S.; Littman, D.R. Blood Monocytes Consist of Two Principal Subsets with Distinct Migratory Properties. Immunity 2003, 19, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, M.A.; Spanbroek, R.; Lottaz, C.; Gautier, E.L.; Frankenberger, M.; Hoffmann, R.; Lang, R.; Haniffa, M.; Collin, M.; Tacke, F.; et al. Comparison of Gene Expression Profiles between Human and Mouse Monocyte Subsets. Blood 2010, 115, e10–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, A.; Coetzee, S.G.; Olsson, A.; Muench, D.E.; Berman, B.P.; Hazelett, D.J.; Salomonis, N.; Grimes, H.L.; Goodridge, H.S. Granulocyte-Monocyte Progenitors and Monocyte-Dendritic Cell Progenitors Independently Produce Functionally Distinct Monocytes. Immunity 2017, 47, 890–902.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papewalis, C.; Jacobs, B.; Baran, A.M.; Ehlers, M.; Stoecklein, N.H.; Willenberg, H.S.; Schinner, S.; Anlauf, M.; Raffel, A.; Cupisti, K.; et al. Increased Numbers of Tumor-Lysing Monocytes in Cancer Patients. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2011, 337, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venneri, M.A.; De Palma, M.; Ponzoni, M.; Pucci, F.; Scielzo, C.; Zonari, E.; Mazzieri, R.; Doglioni, C.; Naldini, L. Identification of Proangiogenic TIE2-Expressing Monocytes (TEMs) in Human Peripheral Blood and Cancer. Blood 2007, 109, 5276–5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettinger, J.; Richards, D.M.; Hansson, J.; Barra, M.M.; Joschko, A.C.; Krijgsveld, J.; Feuerer, M. Origin of Monocytes and Macrophages in a Committed Progenitor. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serbina, N.V.; Hohl, T.M.; Cherny, M.; Pamer, E.G. Selective Expansion of the Monocytic Lineage Directed by Bacterial Infection. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 1900–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akashi, K.; Traver, D.; Miyamoto, T.; Weissman, I.L. A Clonogenic Common Myeloid Progenitor That Gives Rise to All Myeloid Lineages. Nature 2000, 404, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.P.; Thomas, G.D.; Hedrick, C.C. Transcriptional Control of Monocyte Development. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzebanski, S.; Kim, J.S.; Larossi, N.; Raanan, A.; Kancheva, D.; Bastos, J.; Haddad, M.; Solomon, A.; Sivan, E.; Aizik, D.; et al. Classical Monocyte Ontogeny Dictates Their Functions and Fates as Tissue Macrophages. Immunity 2024, 57, 1225–1242.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gu, Y.; Chakarov, S.; Bleriot, C.; Kwok, I.; Chen, X.; Shin, A.; Huang, W.; Dress, R.J.; Dutertre, C.A.; et al. Fate Mapping via Ms4a3-Expression History Traces Monocyte-Derived Cells. Cell 2019, 178, 1509–1525.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.G.; Liu, Z.; Kwok, I.; Ginhoux, F. Origin and Heterogeneity of Tissue Myeloid Cells: A Focus on GMP-Derived Monocytes and Neutrophils. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 41, 375–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, F.; Arkin, Y.; Giladi, A.; Jaitin, D.A.; Kenigsberg, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Winter, D.; Lara-Astiaso, D.; Gury, M.; Weiner, A.; et al. Transcriptional Heterogeneity and Lineage Commitment in Myeloid Progenitors. Cell 2015, 163, 1663–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, A.; Venkatasubramanian, M.; Chaudhri, V.K.; Aronow, B.J.; Salomonis, N.; Singh, H.; Grimes, H.L. Single-Cell Analysis of Mixed-Lineage States Leading to a Binary Cell Fate Choice. Nature 2016, 537, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giladi, A.; Paul, F.; Herzog, Y.; Lubling, Y.; Weiner, A.; Yofe, I.; Jaitin, D.; Cabezas-Wallscheid, N.; Dress, R.; Ginhoux, F.; et al. Single-Cell Characterization of Haematopoietic Progenitors and Their Trajectories in Homeostasis and Perturbed Haematopoiesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, R.N.; Carlin, L.M.; Hubbeling, H.G.; Nackiewicz, D.; Green, A.M.; Punt, J.A.; Geissmann, F.; Hedrick, C.C. The Transcription Factor NR4A1 (Nur77) Controls Bone Marrow Differentiation and the Survival of Ly6C- Monocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, C.; Scadden, E.W.; Wong, L.P.; Schiroli, G.; Mazzola, M.C.; Chea, P.L.; Kato, H.; Hoyer, F.F.; Mistry, M.; Lee, B.K.; et al. Limited Plasticity of Monocyte Fate and Function Associated with Epigenetic Scripting at the Level of Progenitors. Blood 2023, 142, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodridge, H.S. Progenitor Diversity Defines Monocyte Roles. Blood 2023, 142, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olingy, C.E.; Dinh, H.Q.; Hedrick, C.C. Monocyte Heterogeneity and Functions in Cancer. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 106, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglietta, S.; Krieg, C. Phenotypic and Functional Heterogeneity of Monocytes in Health and Cancer in the Era of High Dimensional Technologies. Blood Rev. 2023, 58, 101012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.L.; Tai, J.J.Y.; Wong, W.C.; Han, H.; Sem, X.; Yeap, W.H.; Kourilsky, P.; Wong, S.C. Gene Expression Profiling Reveals the Defining Features of the Classical, Intermediate, and Nonclassical Human Monocyte Subsets. Blood 2011, 118, e16–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Schardey, J.; Wirth, U.; von Ehrlich-Treuenstätt, V.; Neumann, J.; Gießen-Jung, C.; Werner, J.; Bazhin, A.V.; Kühn, F. Analysis of Circulating Immune Subsets in Primary Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, A.; Han, C.Z.; Glass, C.K.; Pollard, J.W. Monocyte Regulation in Homeostasis and Malignancy. Trends Immunol. 2021, 42, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.A.; Zhang, Y.; Fullerton, J.N.; Boelen, L.; Rongvaux, A.; Maini, A.A.; Bigley, V.; Flavell, R.A.; Gilroy, D.W.; Asquith, B.; et al. The Fate and Lifespan of Human Monocyte Subsets in Steady State and Systemic Inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serbina, N.V.; Pamer, E.G. Monocyte Emigration from Bone Marrow during Bacterial Infection Requires Signals Mediated by Chemokine Receptor CCR2. Nat. Immunol. 2006, 7, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunsmore, G.; Guo, W.; Li, Z.; Bejarano, D.A.; Pai, R.; Yang, K.; Kwok, I.; Tan, L.; Ng, M.; De La Calle Fabregat, C.; et al. Timing and Location Dictate Monocyte Fate and Their Transition to Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Sci. Immunol. 2024, 9, eadk3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Lang, D. Life span of monocytes and platelets: Importance of interactions. Front. Biosci. 2009, 14, 2432–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schauer, D.; Starlinger, P.; Reiter, C.; Jahn, N.; Zajc, P.; Buchberger, E.; Bachleitner-Hofmann, T.; Bergmann, M.; Stift, A.; Gruenberger, T.; et al. Intermediate Monocytes but Not TIE2-Expressing Monocytes Are a Sensitive Diagnostic Indicator for Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawada, A.M.; Rogacev, K.S.; Rotter, B.; Winter, P.; Marell, R.R.; Fliser, D.; Heine, G.H. SuperSAGE Evidence for CD14++CD16+ Monocytes as a Third Monocyte Subset. Blood 2011, 118, e50–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cros, J.; Cagnard, N.; Woollard, K.; Patey, N.; Zhang, S.Y.; Senechal, B.; Puel, A.; Biswas, S.K.; Moshous, D.; Picard, C.; et al. Human CD14dim Monocytes Patrol and Sense Nucleic Acids and Viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 Receptors. Immunity 2010, 33, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapellos, T.S.; Bonaguro, L.; Gemünd, I.; Reusch, N.; Saglam, A.; Hinkley, E.R.; Schultze, J.L. Human Monocyte Subsets and Phenotypes in Major Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olingy, C.E.; San Emeterio, C.L.; Ogle, M.E.; Krieger, J.R.; Bruce, A.C.; Pfau, D.D.; Jordan, B.T.; Peirce, S.M.; Botchwey, E.A. Non-Classical Monocytes Are Biased Progenitors of Wound Healing Macrophages during Soft Tissue Injury. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, N.; Kowalska, W.; Zarobkiewicz, M.; Mazurek, M.; Mrozowska, K.; Bojarska-Junak, A.; Rola, R. Pro- vs. Anti-Inflammatory Features of Monocyte Subsets in Glioma Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, C.; Tazzyman, S.; Webster, S.; Lewis, C.E. Expression of Tie-2 by Human Monocytes and Their Responses to Angiopoietin-2. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 7405–7411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Ying, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, L.; Cai, E.; Qian, J.; Cai, J. Circulating Tie2-Expressing Monocytes: A Potential Biomarker for Cervical Cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 8877–8885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffelt, S.B.; Tal, A.O.; Scholz, A.; De Palma, M.; Patel, S.; Urbich, C.; Biswas, S.K.; Murdoch, C.; Plate, K.H.; Reiss, Y.; et al. Angiopoietin-2 Regulates Gene Expression in TIE2-Expressing Monocytes and Augments Their Inherent Proangiogenic Functions. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 5270–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, M.; Venneri, M.A.; Galli, R.; Sergi, L.S.; Politi, L.S.; Sampaolesi, M.; Naldini, L. Tie2 Identifies a Hematopoietic Lineage of Proangiogenic Monocytes Required for Tumor Vessel Formation and a Mesenchymal Population of Pericyte Progenitors. Cancer Cell 2005, 8, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudard, S.; Benhamouda, N.; Escudier, B.; Ravel, P.; Tran, T.; Levionnois, E.; Negrier, S.; Barthelemy, P.; Berdah, J.F.; Gross-Goupil, M.; et al. Decrease of Pro-Angiogenic Monocytes Predicts Clinical Response to Anti-Angiogenic Treatment in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cells 2022, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Acker, H.H.; Van Acker, Z.P.; Versteven, M.; Ponsaerts, P.; Pende, D.; Berneman, Z.N.; Anguille, S.; Van Tendeloo, V.F.; Smits, E.L. CD56 Homodimerization and Participation in Anti-Tumor Immune Effector Cell Functioning: A Role for Interleukin-15. Cancers 2019, 11, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horzum, U.; Yoyen-Ermis, D.; Taskiran, E.Z.; Yilmaz, K.B.; Hamaloglu, E.; Karakoc, D.; Esendagli, G. CD66b+ Monocytes Represent a Proinflammatory Myeloid Subpopulation in Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 70, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrò, A.; Drommi, F.; Sidoti Migliore, G.; Pezzino, G.; Vento, G.; Freni, J.; Costa, G.; Cavaliere, R.; Bonaccorsi, I.; Sionne, M.; et al. Neutrophil-like Monocytes Increase in Patients with Colon Cancer and Induce Dysfunctional TIGIT+ NK Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Yan, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Inflammation and Tumor Progression: Signaling Pathways and Targeted Intervention. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.W.; Choi, H.J.; Ha, S.J.; Lee, K.T.; Kwon, Y.G. Recruitment of Monocytes/Macrophages in Different Tumor Microenvironments. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2013, 1835, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartneck, J.; Hartmann, A.K.; Stein, L.; Arnold-Schild, D.; Klein, M.; Stassen, M.; Marini, F.; Pielenhofer, J.; Meiser, S.L.; Langguth, P.; et al. Tumor-Infiltrating CCR2+ Inflammatory Monocytes Counteract Specific Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1267866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, B.Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Kitamura, T.; Zhang, J.; Campion, L.R.; Kaiser, E.A.; Snyder, L.A.; Pollard, J.W. CCL2 Recruits Inflammatory Monocytes to Facilitate Breast-Tumour Metastasis. Nature 2011, 475, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Xia, R.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Role of the CCL2-CCR2 Signalling Axis in Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targeting. Cell Prolif. 2021, 54, e13115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, X. The Origin and Function of Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2015, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Mohammadian, S.; Vazini, H.; Taghadosi, M.; Esmaeili, S.A.; Mardani, F.; Seifi, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage Plasticity, Polarization, and Function in Health and Disease. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Martin, E.M.; Mellows, T.W.P.; Clarke, J.; Ganesan, A.P.; Wood, O.; Cazaly, A.; Seumois, G.; Chee, S.J.; Alzetani, A.; King, E.V.; et al. M1Hot Tumor-Associated Macrophages Boost Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Infiltration and Survival in Human Lung Cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.N.; Rodriguez, C.; Hubert, M.; Ardin, M.; Treilleux, I.; Ries, C.H.; Lavergne, E.; Chabaud, S.; Colombe, A.; Trédan, O.; et al. CD163+ Tumor-Associated Macrophage Accumulation in Breast Cancer Patients Reflects Both Local Differentiation Signals and Systemic Skewing of Monocytes. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2020, 9, e1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaintreuil, P.; Kerreneur, E.; Bourgoin, M.; Savy, C.; Favreau, C.; Robert, G.; Jacquel, A.; Auberger, P. The Generation, Activation, and Polarization of Monocyte-Derived Macrophages in Human Malignancies. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1178337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimen, M.; Yates, C.M.; McGettrick, H.M.; Ward, L.S.C.; Harrison, M.J.; Apta, B.; Dib, L.H.; Imhof, B.A.; Harrison, P.; Nash, G.B.; et al. Monocyte Subsets Coregulate Inflammatory Responses by Integrated Signaling through TNF and IL-6 at the Endothelial Cell Interface. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 2834–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, R.N.; Cekic, C.; Sag, D.; Tacke, R.; Thomas, G.D.; Nowyhed, H.; Herrley, E.; Rasquinha, N.; McArdle, S.; Wu, R.; et al. Patrolling Monocytes Control Tumor Metastasis to the Lung. Science 2015, 350, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, P.B.; Eggert, T.; Zhu, Y.P.; Marcovecchio, P.; Meyer, M.A.; Wu, R.; Hedrick, C.C. Patrolling Monocytes Control NK Cell Expression of Activating and Stimulatory Receptors to Curtail Lung Metastases. J. Immunol. 2019, 204, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, L.E.; Marcovecchio, P.M.; Olingy, C.E.; Araujo, D.J.; Steel, K.; Dinh, H.Q.; Alimadadi, A.; Zhu, Y.P.; Meyer, M.A.; Kiosses, W.B.; et al. Nonclassical Monocytes Potentiate Anti-Tumoral CD8+ T Cell Responses in the Lungs. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1101497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Pamer, E.G. Monocyte Recruitment during Infection and Inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Bao, W.; Pal, M.; Liu, Y.; Yazdanbakhsh, K.; Zhong, H. Intermediate Monocytes Induced by IFN-γ Inhibit Cancer Metastasis by Promoting NK Cell Activation through FOXO1 and Interleukin-27. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Deng, S.; Tang, W.; Hu, X.; Yin, F.; Ge, H.; Tang, J.; Liao, Z.; Li, X.; Feng, J. Recruitment of IL-1β-Producing Intermediate Monocytes Enhanced by C5a Contributes to the Development of Malignant Pleural Effusion. Thorac. Cancer 2022, 13, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastio, J.; Condamine, T.; Dominguez, G.; Kossenkov, A.V.; Donthireddy, L.; Veglia, F.; Lin, C.; Wang, F.; Fu, S.; Zhou, J.; et al. Identification of Monocyte-like Precursors of Granulocytes in Cancer as a Mechanism for Accumulation of PMN-MDSCs. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 2150–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, M.; Halasz, L.; Hadadi, E.; Berger, W.K.; Tzerpos, P.; Poliska, S.; Kancheva, D.; Gabriel, A.; Mora Barthelmess, R.; Debraekeleer, A.; et al. Epigenomic Preconditioning of Peripheral Monocytes Determines Their Transcriptional Response to the Tumor Microenvironment. Genome Med. 2025, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergenfelz, C.; Leandersson, K. The Generation and Identity of Human Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Li, Z.; Gao, R.; Xing, B.; Gao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Qin, S.; Zhang, L.; Ouyang, H.; Du, P.; et al. A Pan-Cancer Single-Cell Transcriptional Atlas of Tumor Infiltrating Myeloid Cells. Cell 2021, 184, 792–809.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, R.; Fiore, A.; Sartori, S.; Canè, S.; Giugno, R.; Cascione, L.; Paiella, S.; Salvia, R.; De Sanctis, F.; Poffe, O.; et al. Immunosuppression by Monocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Carcinoma Is Orchestrated by STAT3. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Cagnon, L.; Costa-Nunes, C.M.; Baumgaertner, P.; Montandon, N.; Leyvraz, L.; Michielin, O.; Romano, E.; Speiser, D.E. Frequencies of Circulating MDSC Correlate with Clinical Outcome of Melanoma Patients Treated with Ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014, 63, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ma, J.; Tang, K.; Xu, P.; Ji, T.; Liang, X.; Lv, J.; Dong, W.; et al. Circulating Tumor Microparticles Promote Lung Metastasis by Reprogramming Inflammatory and Mechanical Niches via a Macrophage-Dependent Pathway. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 1046–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, B.Z.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophage Diversity Enhances Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Cell 2010, 141, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Gai, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tian, K.; Liu, P.; Liang, H.; Xu, X.; Peng, Q.; Luo, X. Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor and Its Role in the Tumor Microenvironment: Novel Therapeutic Avenues and Mechanistic Insights. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1358750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.H.; Chen, F.M.; Lin, Y.C.; Tsai, M.L.; Wang, S.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.T.; Hou, M.F. Altered Monocyte Differentiation and Macrophage Polarization Patterns in Patients with Breast Cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhang, G.; Sun, B.; Yuan, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Hou, J. The Frequency of Tumor-Infiltrating Tie-2-Expressing Monocytes in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Its Relationship to Angiogenesis and Progression. Urology 2013, 82, 974.e9–974.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, S.; Henry, L.; Faes-van’t Hull, E.; Turrini, R.; Vanhecke, D.; Guex, N.; Ifticene-Treboux, A.; Marina Iancu, E.; Semilietof, A.; Rufer, N.; et al. TIE-2-Expressing Monocytes Are Lymphangiogenic and Associate Specifically with Lymphatics of Human Breast Cancer. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1073882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanik, H.; Demir, I.; Celik, E.; Tavukcuoglu, E.; Bahcecioglu, I.B.; Bahcecioglu, A.B.; Hidiroglu, M.M.; Guler, S.; Ersoz Gulcelik, N.; Gulcelik, M.A.; et al. CD66b+ Tumor-Infiltrating Neutrophil-like Monocytes as Potential Biomarkers for Clinical Decision-Making in Thyroid Cancer. Medicina 2025, 61, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwart, D.; He, J.; Srivatsan, S.; Lett, C.; Golubov, J.; Oswald, E.M.; Poon, P.; Ye, X.; Waite, J.; Zaretsky, A.G.; et al. Cancer Cell-Derived Type I Interferons Instruct Tumor Monocyte Polarization. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patysheva, M.R.; Fedorenko, A.A.; Khozyainova, A.A.; Denisov, E.V.; Gerashchenko, T.S. Immune Evasion in Cancer Metastasis: An Unappreciated Role of Monocytes. Cancers 2025, 17, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, T.; Kamiyama, A.; Sawada, H.; Kikuchi, K.; Maruyama, M.; Sawado, R.; Ikeda, N.; Asano, K.; Kurotaki, D.; Tamura, T.; et al. Immunoregulatory Monocyte Subset Promotes Metastasis Associated with Therapeutic Intervention for Primary Tumor. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 663115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Chung, H.; Kim, J.; Choi, D.H.; Shin, Y.; Kang, Y.G.; Kim, B.M.; Seo, S.U.; Chung, S.; Seok, S.H. Macrophages-Triggered Sequential Remodeling of Endothelium-Interstitial Matrix to Form Pre-Metastatic Niche in Microfluidic Tumor Microenvironment. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnakota, K.; Zhang, Y.; Selvanesan, B.C.; Topi, G.; Salim, T.; Sand-Dejmek, J.; Jönsson, G.; Sjölander, A. M2-like Macrophages Induce Colon Cancer Cell Invasion via Matrix Metalloproteinases. J. Cell Physiol. 2017, 232, 3468–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, B.; Wang, N.; D’Costa, Z.; Fernandez, M.C.; Bourdeau, F.; Auguste, P.; Illemann, M.; Eefsen, R.L.; Høyer-Hansen, G.; Vainer, B.; et al. TNF Receptor-2 Facilitates an Immunosuppressive Microenvironment in the Liver to Promote the Colonization and Growth of Hepatic Metastases. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 5235–5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongre, A.; Weinberg, R.A. New Insights into the Mechanisms of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Implications for Cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owyong, M.; Chou, J.; van den Bijgaart, R.J.E.; Kong, N.; Efe, G.; Maynard, C.; Talmi-Frank, D.; Solomonov, I.; Koopman, C.; Hadler-Olsen, E.; et al. MMP9 Modulates the Metastatic Cascade and Immune Landscape for Breast Cancer Anti-Metastatic Therapy. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201800226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibberson, M.; Bron, S.; Guex, N.; Hull, E.F.V.; Ifticene-Treboux, A.; Henry, L.; Lehr, H.A.; Delaloye, J.F.; Coukos, G.; Xenarios, I.; et al. TIE-2 and VEGFR Kinase Activities Drive Immunosuppressive Function of TIE-2-Expressing Monocytes in Human Breast Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 3439–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patysheva, M.; Larionova, I.; Stakheyeva, M.; Grigoryeva, E.; Iamshchikov, P.; Tarabanovskaya, N.; Weiss, C.; Kardashova, J.; Frolova, A.; Rakina, M.; et al. Effect of Early-Stage Human Breast Carcinoma on Monocyte Programming. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 800235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, A.L.; Zhu, J.K.; Sun, J.T.; Yang, M.X.; Neckenig, M.R.; Wang, X.W.; Shao, Q.Q.; Song, B.F.; Yang, Q.F.; Kong, B.H.; et al. CD16+ Monocytes in Breast Cancer Patients: Expanded by Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 and May Be Useful for Early Diagnosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2011, 164, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, A.M.; Nordström, O.; Johansson, A.; Rydén, L.; Leandersson, K.; Bergenfelz, C. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Populations Correlate with Outcome in Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, L.; Fragkogianni, S.; Sims, A.H.; Swierczak, A.; Forrester, L.M.; Zhang, H.; Soong, D.Y.H.; Cotechini, T.; Anur, P.; Lin, E.Y.; et al. Human Tumor-Associated Macrophage and Monocyte Transcriptional Landscapes Reveal Cancer-Specific Reprogramming, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targets. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 588–602.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knöbl, V.; Maier, L.; Grasl, S.; Kratzer, C.; Winkler, F.; Eder, V.; Hayden, H.; Sahagun Cortez, M.A.; Sachet, M.; Oehler, R.; et al. Monocyte Subsets in Breast Cancer Patients under Treatment with Aromatase Inhibitor and Mucin-1 Cancer Vaccine. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergenfelz, C.; Larsson, A.M.; Von Stedingk, K.; Gruvberger-Saal, S.; Aaltonen, K.; Jansson, S.; Jernström, H.; Janols, H.; Wullt, M.; Bredberg, A.; et al. Systemic Monocytic-MDSCs Are Generated from Monocytes and Correlate with Disease Progression in Breast Cancer Patients. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prat, M.; Le Naour, A.; Coulson, K.; Lemée, F.; Leray, H.; Jacquemin, G.; Rahabi, M.C.; Lemaitre, L.; Authier, H.; Ferron, G.; et al. Circulating CD14 High CD16 Low Intermediate Blood Monocytes as a Biomarker of Ascites Immune Status and Ovarian Cancer Progression. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, H.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Huang, X.; Ni, Y. Frequency of Circulating CD14++ CD16+ Intermediate Monocytes as Potential Biomarker for the Diagnosis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, G.; Dino, K.; Schierle, K.; Dietel, C.; Aust, G.; Pratschke, J.; Seehofer, D.; Schmelzle, M.; Hau, H.M. Angiogenic Inflammation and Formation of Necrosis in the Tumor Microenvironment Influence Patient Survival after Radical Surgery for de Novo Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Non-Cirrhosis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 17, 139659377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, C.E.; De Palma, M.; Naldini, L. Tie2-Expressing Monocytes and Tumor Angiogenesis: Regulation by Hypoxia and Angiopoietin-2. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8429–8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, A.S.; Agbaje, K.; Adesina, S.K.; Olajubutu, O. Colorectal Cancer: Disease Process, Current Treatment Options, and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiaie, S.H.; Sanaei, M.J.; Heshmati, M.; Asadzadeh, Z.; Azimi, I.; Hadidi, S.; Jafari, R.; Baradaran, B. Immune Checkpoints in Targeted-Immunotherapy of Pancreatic Cancer: New Hope for Clinical Development. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 1083–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, E.; Ahmed, S. Principles of Cancer Treatment by Chemotherapy. Surgery 2018, 36, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, H.; Ramapriyan, R.; Cushman, T.R.; Verma, V.; Kim, H.H.; Schoenhals, J.E.; Atalar, C.; Selek, U.; Chun, S.G.; Chang, J.Y.; et al. Role of Radiation Therapy in Modulation of the Tumor Stroma and Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lin, Y.; Li, R.; Shen, X.; Xiang, M.; Xiong, G.; Zhang, K.; Xia, T.; Guo, J.; Miao, Z.; et al. Molecular Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Current and Evolving Approaches. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1165666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, K.; Stadler, Z.K.; Cercek, A.; Mendelsohn, R.B.; Shia, J.; Segal, N.H.; Diaz, L.A. Immunotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: Rationale, Challenges and Potential. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkgraaf, E.M.; Heusinkveld, M.; Tummers, B.; Vogelpoel, L.T.C.; Goedemans, R.; Jha, V.; Nortier, J.W.R.; Welters, M.J.P.; Kroep, J.R.; Van Der Burg, S.H. Chemotherapy Alters Monocyte Differentiation to Favor Generation of Cancer-Supporting M2 Macrophages in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2480–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getter, M.A.; Bui-Nguyen, T.M.; Rogers, L.M.; Ramakrishnan, S. Chemotherapy Induces Macrophage Chemoattractant Protein-1 Production in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2010, 20, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Wang, F.; Dai, C.; Wu, F.; Liu, X.; Li, T.; Glauben, R.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, G.; et al. Tie2 Expression on Macrophages Is Required for Blood Vessel Reconstruction and Tumor Relapse after Chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 6828–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Deng, L.; Hou, Y.; Meng, X.; Huang, X.; Rao, E.; Zheng, W.; Mauceri, H.; Mack, M.; Xu, M.; et al. Host STING-Dependent MDSC Mobilization Drives Extrinsic Radiation Resistance. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadepalli, S.; Clements, D.R.; Saravanan, S.; Hornero, R.A.; Lüdtke, A.; Blackmore, B.; Paulo, J.A.; Gottfried-Blackmore, A.; Seong, D.; Park, S.; et al. Rapid Recruitment and IFN-I–Mediated Activation of Monocytes Dictate Focal Radiotherapy Efficacy. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, eadd7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Ji, D.; Tao, Z.; Hu, X. Baseline Monocyte and Its Classical Subtype May Predict Efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitor in Cancers. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20202613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.; Heishi, T.; Khan, O.F.; Kowalski, P.S.; Incio, J.; Rahbari, N.N.; Chung, E.; Clark, J.W.; Willett, C.G.; Luster, A.D.; et al. Ly6Clo Monocytes Drive Immunosuppression and Confer Resistance to Anti-VEGFR2 Cancer Therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3039–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Heishi, T.; Incio, J.; Huang, Y.; Beech, E.Y.; Pinter, M.; Ho, W.W.; Kawaguchi, K.; Rahbari, N.N.; Chung, E.; et al. Targeting CXCR4-Dependent Immunosuppressive Ly6Clow Monocytes Improves Antiangiogenic Therapy in Colorectal Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10455–10460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H.; Xie, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, D.; et al. CSF1R Inhibition Reprograms Tumor-Associated Macrophages to Potentiate Anti-PD-1 Therapy Efficacy against Colorectal Cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 202, 107126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassetti, C.; Insinga, G.; Gimigliano, F.; Morrione, A.; Giordano, A.; Giurisato, E. Insights into CSF-1R Expression in the Tumor Microenvironment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yao, W.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, P.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Chu, R.; Song, H.; Xie, D.; Jiang, X.; et al. Targeting of Tumour-Infiltrating Macrophages via CCL2/CCR2 Signalling as a Therapeutic Strategy against Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut 2017, 66, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonapace, L.; Coissieux, M.M.; Wyckoff, J.; Mertz, K.D.; Varga, Z.; Junt, T.; Bentires-Alj, M. Cessation of CCL2 Inhibition Accelerates Breast Cancer Metastasis by Promoting Angiogenesis. Nature 2014, 515, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stift, A.; Friedl, J.; Dubsky, P.; Bachleitner-Hofmann, T.; Schueller, G.; Zontsich, T.; Benkoe, T.; Radelbauer, K.; Brostjan, C.; Jakesz, R.; et al. Dendritic cell-based vaccination in solid cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, S.; Dorigo, O. Monocytes: A Promising New TRAIL in Ovarian Cancer Cell Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafi, S.; Mortezaee, K. Advances in dendritic cell vaccination therapy of cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sahagun Cortez, M.A.; Eilenberg, W.; Neumayer, C.; Brostjan, C. Distinct Roles of Monocyte Subsets in Cancer. Cells 2025, 14, 1982. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241982

Sahagun Cortez MA, Eilenberg W, Neumayer C, Brostjan C. Distinct Roles of Monocyte Subsets in Cancer. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1982. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241982

Chicago/Turabian StyleSahagun Cortez, Maria Amparo, Wolf Eilenberg, Christoph Neumayer, and Christine Brostjan. 2025. "Distinct Roles of Monocyte Subsets in Cancer" Cells 14, no. 24: 1982. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241982

APA StyleSahagun Cortez, M. A., Eilenberg, W., Neumayer, C., & Brostjan, C. (2025). Distinct Roles of Monocyte Subsets in Cancer. Cells, 14(24), 1982. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241982